Photo

Gig Posters

Some playful posters I created for Glasgow based musician Michael & the Moonshine. Graphic design & illustration is always a pleasing break from intensive design engineering projects.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Electromagnetism

Excellent educational GIFs from blogger, Physics Girl.

0 notes

Photo

18 Designers Predict UI/UX Trends for 2018

This was a really insightful post I happened upon this evening. There’s encouraging emphasis on accessibility and inclusivity in UI/UX, something which is all too often ignored in favour of a slick aesthetic.

The second ‘trend’ identified which really resonated with me is the move towards more collaboration and less ego, as Nicole Tollefson describes so well here;

“Many still find it uncomfortable to invite “non-designers” into their headspace and discover that their best design is ultimately 90% (or more) other peoples’ input and 10% (or less) their own ideas, but the most successful teams and companies have known this about design for a long time.” I completely agree, and admit, that each one of my individual projects has benefited from conversation (or observation at the very least), be it with potential users, classmates, friends or strangers. Good design doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

0 notes

Video

vimeo

IDEO Gesture demo from David Rose on Vimeo. “Of the existing interaction modalities—haptics (touch), sound (voice), and vision (gesture)—which is better to use when, and why?” “We discovered that gestures need to be either sequential, like a sentence—noun then verb, object plus operation. For example, for “speaker, on,” one hand designates the noun, and the other the verb: You point to speaker with left hand and turn the volume up by raising right hand. Another surprising insight: Gestures are generation-specific. When asked to signal turning up the volume, a few people twisted an invisible knob, but most of the under 30s lifted a palm or made a pinching gesture with their fingers” “After analyzing our results, we boiled our thoughts down to four reasons to opt for gesture over voice or touch:

Speed: If it needs to be fast, gestures are much quicker than speaking sentences.

Distance: If you need to communicate from across the room, gesture is easier than dealing with volume.

Limited lexicon: If you don't have a thousand things to say, gestures work well. The smaller the gesture set for a given context, the easier it is to remember. (Thumbs-up/thumbs-down, for example.)

Expressiveness over precision: Gestures are well-suited to expressing emotional salience. A musical conductor communicates a downbeat and tempo, but also so much more: dolco, marcato, confidence, sadness, longing, and more.It's exciting to imagine a whole new category of products that will take advantage of gesture’s subtlety, expressiveness, and speed.” Some really interesting points from an IDEO article by David Rose, wherein the Cambridge Studio investigated gesture control and speculated on its place in our future interactions. I explored this modality in my recent Human Factors project about future smart energy meters, but obviously not in as much depth as this design studio. The article support the reasons I chose to integrate gesture control into my project and articulates them in a way I wasn’t able to. Is there a way gesture control could be used in my current project? How might it help visually impaired people, and everybody, control their cooktop? Intriguing! #gesturecontrol

0 notes

Text

Re-blog: Ross Atkin’s talk at the Global Disability Innovation Summit

“I was invited to speak at the Global Disability Innovation Summit held at Here East on the Olympic Park in London. I shared a slot with Tom Watt-Smith, the showrunner (producer and director) for The Big Life Fix. Tom introduced the program and covered the cultural trends that lead to a program about assistive technology getting commissioned in a primetime slot on BBC2. I used my slot to reflect on the approach we took to developing technology during the program and look at the strengths and weaknesses of scaling it to help more disabled people. I drew on some of the arguments Sam Jewell and I made in our 2013 report ‘Enabling Technology‘ which was commissioned by Scope, BT and the RCA Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design.

—

On the Big Life Fix we, as designers and technologists, got to do something that we don’t often get to do – build technology products specifically for particular disabled individuals.

This work is in a totally different mindset from doing the ‘industrial design’ most of us do in our day jobs. Even user-centred industrial design.

There you are designing for a ‘segment’ that includes a large number of people. You try and recruit users that are representative of the segment and design around their needs, but you must focus on the needs and preferences that are common to multiple users.

Being able to focus, as we did in the Big Life Fix, not on a segment but on an individual user was an incredible privilege. It took us, and the audience, on an emotional journey,

and it was always crystal clear whether or not we had made the right thing.

Being realistic though, even at the bargain basement rates that the BBC paid us, the cost this kind of work would be beyond the means of the vast majority of disabled people. If we weren’t subsidising that work with our other jobs it would have been an order of magnitude more expensive still.

This reality check doesn’t mean that the approach we took can not benefit more disabled people, beyond those involved in the program.

I was lucky enough to have been able to explore these issues back in 2013 in a research project for Scope and the Helen Hamlyn Centre with Sam Jewell.

We realised that there was a fundamental equation at play when industrial design economics are applied to assistive technology.

As disabled people are very different from one another, the assistive technology that works best for an individual is often one that is aimed at a very narrow segment – or small group of people.

The problem is that set-up costs for industrial manufacture are usually fixed, so a narrower segment means fewer units to spread those costs over, increasing the cost of those units. This equation explains the eye-watering cost of much assistive technology.

As Sam and I pointed out back in 2013, general purpose electronic devices like smart phones and tablets and affordable digital fabrication technologies like 3D printing and laser cutting, can disrupt this equation – effectively removing this industrial set-up cost.

These are exactly the technologies we used to create the products we made in Big Life Fix and, now the design work is done, theoretically, anyone who wants a robotic camera rig like the one we made for James can download and 3D print the parts, put it together and download the app from iTunes.

How disabled people access the infrastructure to actually do this is an important question, but I’m running out of time.

The last thing I want to say is a defence of industry. Many disabled people don’t want to have to find a makerspace and some hackers, or even a shiny new East London tech startup, to get the products they need to live independently. They want products supported by a organisation they can rely on.

The UK Assistive Technology industry leads the world and is full of dedicated designers and technologists who work every day to improve the lives of thousands of disabled people.

I’m lucky to count some of these companies like Stannah and TFH as clients and I know there is so much we here could do to ensure that more disabled people get the support to benefit from their work.

Outside of assistive tech there is a growing awareness in industry that designing for disability makes business sense. For me getting to work with companies like Marshalls, the UK’s largest manufacturer of landscaping products and Cusack, the largest supplier of roadworks equipment, on accessibility technology projects affords the opportunity to have an impact on the lives of huge numbers of disabled people up and down the country.

I believe that as technologists, reaching out to industry, even in less fashionable parts of the country and focusing on partnership rather than disruption is most likely to maximise the positive impact of our work.” I stumbled upon this blog post by Ross Atkin the other day and I’ve been thinking about it so much I felt compelled to share it. It’s an interesting insight from the unique perspective of a designer who has had the privilege to design for the individual, but due to his industrial experience, he understands that in itself is a privilege. Ruby Steele of Smart Design, also part of the Big Life Fix team, has also spoken on the topic of ‘Designing for one’, and the ability to “restore a bit of humanity to a person who had lost so much.” The inevitable individualism of people with disabilities, the large spectrum of unique cases and challenges, is something I’ve encountered and struggled with whilst trying to improve cooking for the visually impaired. The ability and confidence of each person I spoke to depended on a variety of factors including the level of visual impairment they live with, when they lost their vision, their lifestyle and living arrangements and their access to occupational therapy or understanding friends. Such is the challenge of designing for disability. Ross touches on other themes like the accessibility of design and makerspaces, and the trust in a brand that a generalised solution can bring over an individualised one. Discussion of this issue can spiral and grow, there will always be more to say, some of which Ross explores in his report ‘Enabling Technology’ with the Helen Hamlyn Centre...but this short talk is a good starting point.

#assistivetechnology#enablingtechnology#designfordisability#inclusivedesign#designindustry#designforthe

0 notes

Photo

BIG TOP

Here are some process shots of the making of this giant spinning top, it was our last project, and I had a lot of fun with it. High quality photos by the excellent Robyn. I haven’t weight this plywood beast but it was about 35cm diameter at it’s widest, and took two to operate, special thanks to my glamorous assistant Kevin for his supreme arm span. Great fun, thank you friends.

0 notes

Photo

To Conclude; For more information on biomimicry, check out Janine Benyus, her book and her Ted talks. Her book gives a very broad outlook of biomimetic principles, giving as much detail to agriculture as design. Biomimicry 3.8 is a design practice she has started which has a design lens to help practitioners apply nature’s principles. Sustainability is the greatest design challenge of our time, and I believe biomimicry is a very useful tool to tackle it with. The goal is to create products, processes, and policies—new ways of living—that are well-adapted to life on earth over the long haul, instead of the short-term outlook we usually apply. What humans do over the next 50 years will determine the fate of all life on the planet, according to David Attenborough. Interdisciplinary design, sharing knowledge, could be the route to the best possible future for all. Learning from nature’s principles now can ensure the availability of the opportunity to do so for future generations. Moving beyond biomimicry alone, I truly believe that sharing expertise will bring the most effective progress moving forward. We should not be designing in a vacuum with only Google to consult, but alongside and users, engineers and scientists of all types, psychologists, anthropologists, and craftspeople. So much more is gained from a conversation than an internet search. Collaboration, not competition, will bring us forward.

0 notes

Photo

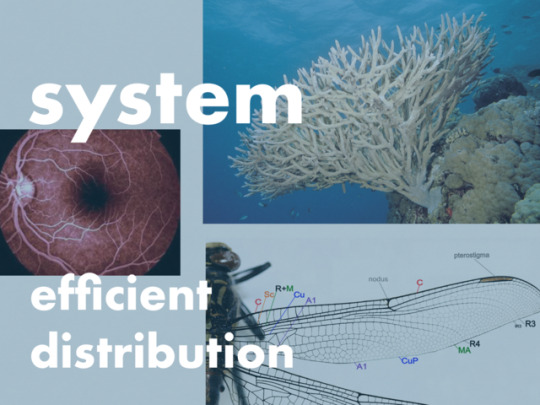

Biomimetic Systems

Again, on a systematic scale, nature outstrips our efforts. There’s evidence that we should design distribution networks based on the looped veins that carry water and nutrients in most tree leaves...for increased resilience (if one section is severed, the water will still reach most of the leaf) and the ability to manage fluctuating loads. This kind of network full of loops can also be found in the blood vessels of the retina, the architecture of corals, and the structural veins of insect wings, because it works! - And it is so much more efficient than the likes of the pipe systems we build with 90 degree corners that create friction... Nature out performs us with certain communication systems too, despite how connected we think our world is. There can be 80 million locusts in a square kilometer, and yet they don’t collide with one another. Meanwhile, the US has 3.6million car collisions a year, we clearly have something to learn regarding sensing and feedback. On a grander scale, each of these individual organisms is inextricably linked to the ecosystem around them, frequently in a symbiotic relationship. The orchestration of nature is incredible, and contains so much we can learn from, especially regarding sustainability and a mutually beneficial relationship with the planet.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

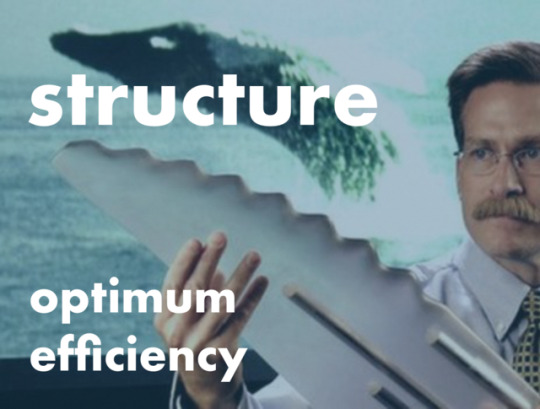

Biomimetic structures

As for structures, nature consistently demonstrates the power of shape. Strong and lightweight structures like spiderwebs or even lily-pads are feats of elegant engineering, not to mention the complexity of our skeletons. Nature is a master of architectural precision.

We all saw this in London in September, the Elytra Filament Pavillion @ the V&A. The design draws on research into lightweight construction found in nature. It is inspired by the filament structure of the shells of flying beetles. Each component of the canopy is produced using a robotic winding technique developed by the designers.

Unlike other fabrication methods, this does not require moulds and can produce an infinite variety of spun shapes, while reducing waste to a minimum…nature would approve. Additive manufacturing is a good step in this direction.

Nature also uses shape and surface to carry out more specific functions very efficiently. The humpback whale, for example, doesn’t look very agile but in fact is highly aerodynamic. The fins have little bumps or tubercles on them, which can increase efficiency over a smooth surface by about 32%.

This could lead to impressive fossil fuel savings if implemented in aircraft - which are already heavily influenced by nature’s flying organisms, but could be improved further by diversifying and looking beyond the obvious counterparts to other species, like the whales. Another surface example, which many of us saw on Attenborough’s Planet Earth II, Micro-sized grooves on this desert beetle’s body can help condense and direct water toward the beetle’s awaiting mouth, while a combination of hydrophilic and hydrophobic areas increase fog- and dew-harvesting efficiency. This technique has already inspired fog nets and a self-filling water bottle. Surface shape can also create colour without pigments by manipulating light, as the peacock does. Imagine being able to self-assemble products with the last few layers playing with light to create colour in an energy efficient way that doesn’t harm the planet like some pigments do.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

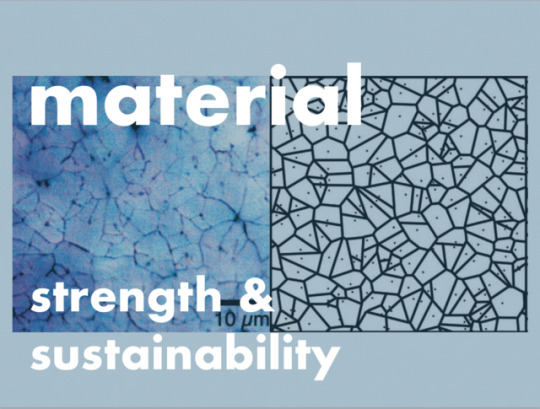

Biomimetic Material

Nature is an expert in sustainability, and creates material continually without waste. Nature self-assembles. Mother of pearl, for example, is a layered structure that’s mineral and then polymer. It’s twice as tough as our high-tech ceramics, but it is formed (almost passively) in seawater, not in kilns. Imagine the energy savings of being able to make ceramics at room temperature by simply dipping something into a liquid, lifting it out of the liquid, and having evaporation force the molecules in the liquid together, just like recrystallisation… Imagine being able to make all of our hard materials that way. Imagine spraying the precursors to a photo-voltaic solar cell, onto a roof, and having it self-assemble into a layered structure that harvests light. No material waste, no energy waste. As smart as nature.Another tactic which helps to eliminate material waste is timed degradation. Packaging or components that only survive long enough to fulfil a role, and then dissolve on cue. This is clearly something we have not gotten the hang of yet, but perhaps some inspiration from nature could help.A mussel in the sea, for example, has threads holding it to a rock which are timed; at exactly two years, they begin to dissolve, releasing the mussel at maturity. Although less precise than that, many natural materials will effortlessly biodegrade, something we’re still learning to replicate.These examples merely scratch the surface of nature’s materials and all they have to offer us, but I think they present a convincing argument that should be investigated more.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Natalie Jeremijenko

“wise, witty and bracingly fierce” ~ New York Times

Natalie Jeremijenko is highly qualified in biochemistry, physics, neuroscience and engineering. Using art, she studies the influence of the environment on our health, and employs technology as an opportunity for social transformation. Jeremijenko explores the interface between biology and design, employing the best of nature to tackle our problems, veering into biomimicry. In her practice, she designs playful and unorthodox social experiments which may seem novel but actually address very real and critical issues associated with Environmental Health.

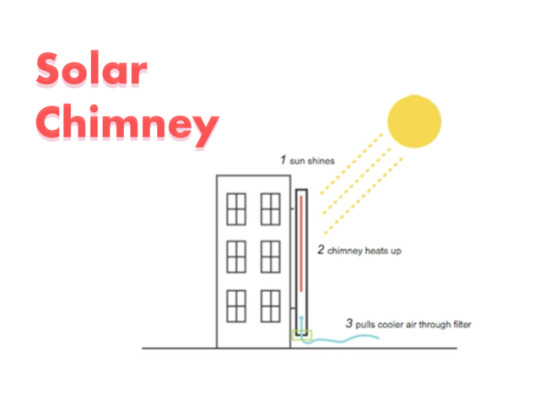

Jeremijenko runs xClinic, a pioneering Environmental Health Clinic at NYU. The X Clinic rather than looking at the internal biology and genetics of an individual, it looks at the surrounding environment and our dependences on it and it prepares the patient for awareness and action. In this clinic, the visitors are not patients but impatients, citizens who are dissatisfied with the local environment and refuse to wait for legislative change, "you walk out with a prescription not for pharmaceuticals but for actions: local data collection and urban interventions directed at understanding and improving your environmental health; plus referrals, not to medical specialists but to specific art, design and participatory projects, local environmental organisations and local government or civil society groups: organisations that can use the data and actions prescribed as legitimate forms of participation to promote social change." She uses a uniquely creative approach to start a conversation on environmental health, and to prescribe action. For example, pet tadpoles to monitor water quality, as they are the most accurate biosensors we have. They react to the same hormone emulators from industry that we do, and their growth is easily observed. She used the results to link water contaminants with the breast cancer and obesity epidemics, and other hormonal health issues. Jeremijenko’s work is bold, artful and makes a serious statement. She has gone beyond merely monitoring, and also devised public interventions to interrupt harmful contaminants in our environment. For example, her solar chimneys employ black plastic tubing to passively draw air through a standard HVAC filter which removes 95% of the carbon black of passing air before it can reach our pretty pink lungs. This carbon black, with ozone, is responsible for about half of global warming's effects, and results from inefficient combustion not combustion itself. The solar chimneys are installed at primary schools across New York, and the carbon black can actually be harvested from the filters and used to make pencils for the students, the length of which measures the grime that has been pulled out of the air. Supreme circularity, while making a mostly invisible pollutant tangible so it can no longer be ignored. Her noPark bio-filtration gardens increase greenery on New York streets while utilising foliage to capture the oily run-off from the road before it enters the river. What she does is takes a "no parking" space associated with a fire hydrant, and prescribes the removal of the asphalt to create an engineered micro landscape, to create an infiltration opportunity. It’s also increasing fixing CO2s and sequestering some of the airborne pollutants. Aggregated, these smaller interceptions could actually infiltrate all the road-borne pollution that now runs into the estuary system. Beyond practicality, experiments like this bring awareness to the invisible environmental crisis which is happening. They also address the crisis of agency associated with environmental matters, “what to do?”. Jeremijenko is pioneering a radical redesign of socioecological systems, creating and exploiting opportunities that require participation and engage the imagination. Instead of the idea that environmentalism is all about doing less, reducing carbon footprint etc, she strives to use the massive force of people as a social good. Action over inaction.

The work of Natalie Jeremijenko creates change and cannot be ignored, my favourite type of art.

0 notes

Photo

The People We Meet

“The People We Meet is an excuse for me to talk to the people I admire. I want to find out how they became who they are and what lies ahead.

We are nothing without each other. We are shaped by the people we meet and the conversations we have. When we surround ourselves with the right people we grow. When we grow we make our corner of the world a better place.” - An excellent little website; beautifully made videos of casual conversations with inspiring creatives. It’s an invitation into the working lives of these people, which feels exclusive and like we’re being let in on some secrets, reminding me of our Design & Tech seminars. The most recent one is concerning Irish illustrator Fuschia Macree (Tumblr didn’t like the video but it is here), where she talks about still feeling imposter syndrome and like she’s “winging it” but about to be found out. I continue to find these insights surprising and comforting, I love the charming glimpses into people’s mindset.

0 notes

Photo

Key Wrangler, by cw&t

A low-profile stainless steel keychain with a spring clip and a post to keep your keys in a tidy row. Quickly clip/unclip onto belt-loops or bags with a snappy carabiner spring gate. Attach your keys onto a secure, easy to open knurled key post.

Interesting prototype gallery of development, but I still find the choice for the final mechanism baffling. A bit over-engineered, if I may say so. The addition of a tool to secure your keys? No thanks, that's overkill.

Still, “323 backers pledged $25,024 to help bring this project to life” on Kickstarter, so consumers obviously connected with it.

0 notes

Photo

D&T 10 : a material journey

Rachael Jane Sleight is driven by a passion for materials and timeless design. She developed an in depth knowledge of manufacturing techniques and process whilst designing and developing accessories, lighting and furniture collections in house for Habitat and Conran. Rachael now has her own studio and continues to work on commissions for leading retailers and manufacturers, while teaching at the Glasgow School of Art.

Rachael initiated a thoughtful discussion about her personal ethics as a designer and how she returns to them time and time again. She showed us different objects spanning her enviable career, and revealed some of the considerations behind them. Browsing her portfolio is a journey through an array of products for different audiences, all elegant and each with a surprising detail;

the visually arresting Wire vase for Conran at M&S, the copper wire pinching the glass into an unusual form which jolts our preconceptions about glass as a material,

the charming Paston console for the same collection, with a thoughtful key bowl and brass letter rack, well considered touchpoints to add some ease and luxe to somebody’s day,

the Crumple flat packed pendant shade for Habitat, working with the wrinkled nature of the Tyvek (and flat-packing) instead of against it, resulting in a warm and textured light-shade,

through to her recent explorations in leather and all of the ethical issues associated with it.

She imbues products with a sweetness and charm which is subtle, not garish, and has a sense of function and familiarity. As a designer she has made herself an expert in tactility, haptics and honest material use, through extensive experimentation. As well as succeeding in making me very jealous of her knowledge and skill, Rachael shared valuable insights in working as a commerical designer and balancing the agendas of different people involved, makers, customers, businesses and herself. Navigating this world after graduation is scary, but these seminars throughout the term have diffused some of that fear by shedding light on the realities of working as a designer, while emphasising crucial advice to centre ourselves and our careers as we please. I am truly grateful to Rachael and the other designers who have spoken to us for their honesty and generosity about these matters. I was captivated by her discussion throughout, and it delights me to have met and learned from another great designer in our midst.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

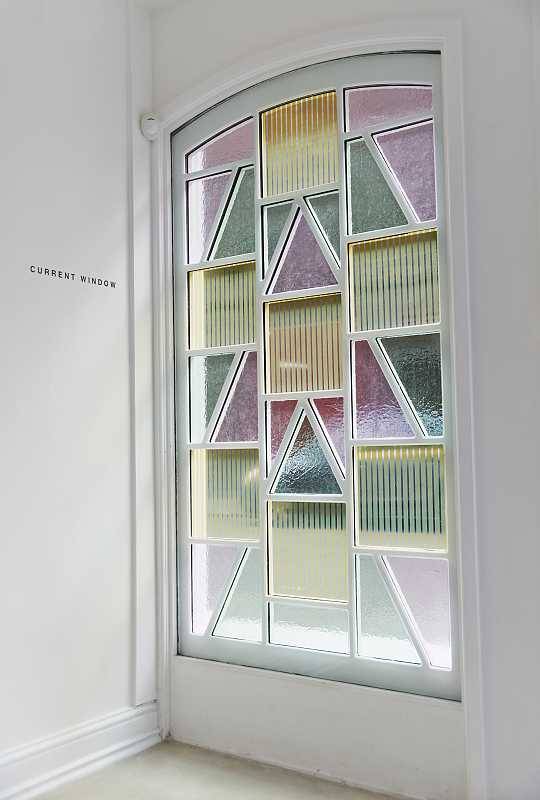

Caventou; Biomimetic, sustainable design

Current Window is a modern version of stained glass — using current technologies. The coloured pieces of glass are generating electricity from daylight, and can even harness diffused sunlight. This electricity can be used to power a whole range of electrical appliances. The glass pieces are made of ‘Dye Sensitised Solar Cells’, which use the properties of colour to create an electrical current — just like photosynthesis in plants. Similarly to the various shades of green chlorophyll absorbing light, the coloured window panes harness energy. Plug in your devices through integrated USB ports in the window ledge. The greater the surface exposed, the more energy will be collected. Imagine these windows in churches, schools, and workplaces! Current Window offers us an example of energy-harvesting in a natural and aesthetic way, for our future.

Caventou was founded by Marjan van Aubel and Peter Krige. Marjan’s research process blends scientific precision with sensory responsiveness to develop aesthetic solutions for the future. Her objects make tangible the potential of technology and energy-harvesting for the benefit of the living environment. Intuitive and inquisitive, she believes interdisciplinary practice is the way forward for design. Peter is an experienced designer and engineer who has developed several successful products such as Beeline, Bare Conductive’s Touch Board and MOOn from concept stage to full scale production. Together they are re-defining solar technology and making it part of everyday life.

These objects, the window and table, integrate solar technology naturally into our daily lives, turning everyday objects into independent power sources that live and breathe energy. This is the kind of biomimicry in design which I really admire, the benefits are tangible and the execution is elegant and seamless. This work captured my imagination when I first happened upon it last year, and has remained in my mind. This is the kind of project I’d love to aspire to looking forward into my final year.

0 notes