#(this is uh. 4725 characters. in one block. in the book)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

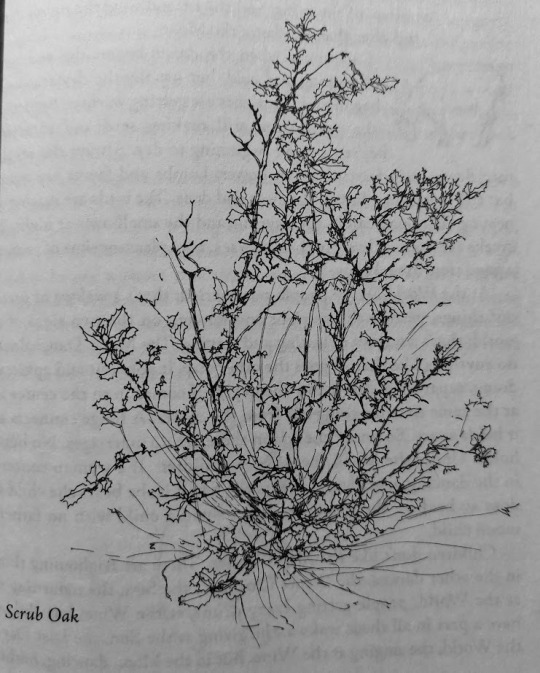

"Pandora, Worrying About What She Is Doing, Finds a Way into the Valley through the Scrub Oak," from Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin

Look how messy this wilderness is. Look at this scrub oak, chaparro, the chaparral was named for it and consists of it mixed up with a lot of other things, but look at this shrub of it right here now. The tallest limb or stem is about four feet tall, but most of the stems are only a foot or two. One of them looks as if it had been cut off with a tool, a clean slice across, but who? what for? This shrub isn’t good for anything and this ridge isn’t on the way to anywhere. A lot of smaller branch-ends look broken or bitten off. Maybe deer browse the leafbuds. The little grey branches and twigs grow every which way, many dead and lichened, crossing each other, choking each other out. Digger-pine needles, spiders’ threads, dead bay leaves are stuck in the branches. It’s a mess. It’s littered. It has no overall shape. Most of the stems come up from one area, but not all; there’s no center and no symmetry. A lot of sticks sticking up out of the ground a little ways with leaves on some of them—that describes it fairly well. The leaves themselves show some order, they seem to obey some laws, poorly. They are all different sizes from about a quarter of an inch to an inch long, but each is enough like the others that one could generalise an ideal scrub-oak leaf: a dusty, medium dark-green color, with a slight convex curve to the leaf, which pillows up a bit between the veins that run slanting outward from the central vein; and the edge is irregularly serrated, with a little spine at each apex. These leaves grow irregularly spaced on alternate sides of their twig up to the top, where they crowd into a bunch, a sloppy rosette. Under the litter of dead leaves, its own and others’, and moss and rocks and mold and junk, the shrub must have a more or less shrub-shaped complex of roots, going fairly deep, probably deeper than it stands aboveground, because wet as it is here now in February, it will be bone dry on this ridge in summer.

There are no acorns left from last fall, if this shrub is old enough to have borne them. It probably is. It could be two years old or twenty or who knows? It is an oak, but a scrub oak, a low oak, a no-account oak, and there are at least a hundred very much like it in sight from this rock I am sitting on, and there are hundreds and thousands and hundreds of thousands more on this ridge and the next ridge, but numbers are wrong. They are in error. You don’t count scrub oaks. When you can count them, something has gone wrong. You can count how many in a hundred square yards and multiply, if you’re a botanist, and so make a good estimate, a fair guess, but you cannot count the scrub oaks on this ridge, let alone the ceanothus, buckbrush, or wild lilac, which I have not mentioned, and the other variously messy and humble components of the chaparral. The chaparral is like atoms and the components of atoms: it evades. It is innumerable. It is not accidentally but essentially messy. This shrub is not beautiful, nor even if I were ten feet high on hashish would it be mystical, nor is it nauseating; if a philosopher found it so, that would be his problem, but nothing to do with the scrub oak. This thing is nothing to do with us. This thing is wilderness. The civilized human mind’s relation to it is imprecise, fortuitous, and full of risk. There are no shortcuts. All the analogies run one direction, our direction. There is a hideous little tumor in one branch. The new leaves, this year’s growth, are so large and symmetrical compared with the older leaves that I took them at first for part of another plant, a toyon growing in with the dwarf oak, but a summer’s dry heat no doubt will shrink them down and warp them. Analogies are easy; the live oak, the humble evergreen, can certainly be made into a sermon, just as it can be made into firewood. Read or burnt. Sermo, I read; I read scrub oak. But I don’t, and it isn’t here to be read, or burnt. It is casting a shadow across the page of this notebook in the weak sunshine of three-thirty of a February afternoon in Northern California. When I close the book and go, the shadow will not be on the page, though I have drawn a line around it; only the pencil line will be on the page. The shadow will be then on the dead-leaf-thick messy ground or on the mossy rock my ass is on now, and the shadow will move lawfully and with great majesty as the earth turns.

The mind can imagine that shadow of a few leaves falling in the wilderness; the mind is a wonderful thing. But what about all the shadows of all the other leaves on all the other branches on all the other scrub oaks on all the other ridges of all the wilderness? If you could imagine those for even a moment, what good would it do? Infinite good.

-- Ursula K. Le Guin, Always Coming Home (273-5)

#did YOU know there's a 4096-character limit on a text block?? i sure as hell didn't#(this is uh. 4725 characters. in one block. in the book)#text#quote#le guin posting#scrub oak#always coming home#ursula k. le guin#this is i think my FAVORITE section in the whole book#i took some liberties with breaking the text block because of the character limit#but i just broke it where my page breaks were (basically. the “there” before the acorns sentence was on page 273 all by its lonesome)#i couldn't figure out what parts to pull out of this passage to quote so i did in fact type the whole thing up#yeah fuck it i'm posting this now and reblogging it in daylight i think

231 notes

·

View notes