#Lexical semantics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lexical semantics will have grown adults discussing whether a tomato is a fruit or a vegetable with the same enthusiasm as primary school children

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Influence of Language on Thought and Perception

The Influence of Language on Thought and Perception Language, the fundamental tool of human communication, is not merely a medium for expressing thoughts but a profound shaper of cognition. The intricate relationship between language and thought has been a subject of fascination for scholars, linguists, and psychologists. As we delve into this complex interplay, we uncover how the languages we…

View On WordPress

#Bilingualism#Cognitive diversity#Cognitive linguistics#Color perception#Cultural linguistics#education#English#english-language#english-learning#Grammatical structures#language#Language and culture#Language and thought#Language evolution#language-learning#languages#learn-english#Lexical semantics#Linguistic anthropology#Linguistic relativity#Metaphors and cognition#Perception and language#Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

0 notes

Text

"its ok, you don't need to know verbs, you're not a linguist, you're a dog" -me, to my dog, right now

#explaining homework to the dog#in my defense it was REALLY COOL homework#like the question had predicates and COM combine to explain why a sentence is fucked up#thats so cool?? what the fuck#like heck yeah “who did he believe the father of will go to the meeting” fuck them up ECM#(the other sentence was like. “who did he convince the father of to go to the meeting” or somthing idk. object control tho)#which. ECM had the “the father of t” be the specIP which COM meant was non grammatical#and on OC it was a PRO thats indexed like it instead. meaning the movement wasn't from there#I even put the fucking. type of island this is. it's SC island. Im so cool you guys and also I fucking hate this#syntax who I only know BURNING HATRED/pos#anyways remind me when I'm doing the syntax seminar next semester that I always have that time around week 7 when I hate syntax#and that I'll get over it and do something epic about sociolingyistic binding phi stuff maybe#like about why all the examples we use are like “mary liked himself” like. why do we assyme marys pronouns. maybe theyre a he/she/they#what part of being a syntactician makes me part of the pronouns police#for the record also this is NOT what I want to research in general but also like#I feel like if anything would get me attention from the syntax folk here it'd be this#bc my morphology things feel. idk. kinda in-between on syntax and semantics. like bc I wanna do lexical meaning of morphemes#which. is not something people here would particularly be looking to investigate. right now#but ooohh Im gonna go learn soo much morpheme stuff#and do the math and coding and experiments. and become a professor and go teach morphology#like pleaseplease you guys I wanna be the morphology teacher at tau soo bad#running silly morpheme building on borrowed words experiments. truly this is using All the things#because borrowed words interacting with morphology is very phonological of me. but also buildings is a syntax/semantics thing#aaaaa I don't knowwww this is such a broad subject and I cant find anything on ittt#linguistics posting

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

technically speaking, javier echeverría is the same name twice

0 notes

Text

Idk why but I just remembered how in my high school French class the teacher said “after this class there’ll be an optional seminar on microaggressions if anybody wants to go” and I asked “but what about macroaggressions?” And she said “…those are just aggressions” and in that moment I felt that words should be much more fun as a general thing if we’ve been at them for thousands of years

1 note

·

View note

Note

are neopronouns actually pronouns?

yes. syntactically, morphologically, lexically, semantically, they are unequivocally pronouns.

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

My hot take is that 'afab' shouldn't be used at all. Spell out the entire phrase in full, every time, because that's the only way to avoid people misusing it that badly.

can’t fucking use afab as a noun, can’t fucking use it as an adjective, do you expect me to go around afabbing? and you answer so many anons do you honestly expect me to go dig through them all looking for a source? i’ve already spent enough of my precious time on this earth arguing with you about this. let’s just stop and go about with our days never having anything to do with each other again.

you're literally getting mad that you "can't use words wrong" you sound like an old conservative man for real. it's a fucking acronym, only use it in sentences where the acronym makes sense.

"assigned female at birth non-binary people" is nonsense. the correct way is "non-binary people assigned female at birth". non-binary people afab. when you use "afab" as an adjective (or a noun) you're basically just using it as a woke stand in for "female". it reinforces a sex binary & deifies the assigned gender dichotomy into something we should be tearing down.

#this is how i feel about the vast majority of acronyms#acronyms lead to lexicalization which leads to semantic drift which leads to afab being used to mean woman#catgirltxt

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Reference: Lexical Blends

A lexical blend - takes two lexemes which overlap in form, and welds them together to make one.

Lexeme - the smallest contrastive unit in a semantic system (run, cat, switch on); also called lexical item.

Some longstanding examples & a few novelties from recent publications:

motor + hotel = motel

breakfast + lunch = brunch

helicopter + airport = heliport

smoke + fog = smog

advertisement + editorial = advertorial

Channel + Tunnel = Chunnel

Oxford + Cambridge = Oxbridge

Yale + Harvard = Yarvard

slang + language = slanguage

guess + estimate = guesstimate

square + aerial = squaerial

toys + cartoons = toytoons

breath + analyser = breathalyser

affluence + influenza = affluenza

information + commercials = infomercials

dock + condominium = dockominium

NOTES

Enough of each lexeme is usually retained so that the elements are recognizable.

In most cases, the second element is the one which controls the meaning of the whole.

Example: "brunch" is a kind of lunch, not a kind of breakfast – which is why the lexeme is brunch and not, say, "lunkfast".

Similarly, a "toytoon" is a kind of cartoon (one which generates a series of shop toys), not a kind of toy.

Blending increased in popularity in the latter half of the 20th century, being increasingly used in commercial and advertising contexts:

Products were sportsational, swimsational, and sexsational.

TV provided dramacons, docufantasies, and rockumentaries.

The forms are felt to be eye-catching and exciting; but how many of them will still be around in 2050 remains an open question.

Source ⚜ Word Lists ⚜ Notes & References

#linguistics#langblr#writeblr#dark academia#writing reference#words#dialogue#spilled ink#literature#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#poets on tumblr#poetry#creative writing#fiction#language#light academia#edmund charles tarbell#writing resources

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

i fucking adore all the little tumblr lexical/semantic/whatever innovations we have on here. Shitposts that are basically site-wide idioms like spiders georg or being at the devil’s sacrament or pissing on the poor. Blorbo and skrunkly and poor little meow meow and how we can have nuanced conversations about these differences between these with some level of coherence. The use of pejoratives and insults like theyre nothing. Prev and grandprev and however-many-times-greatgrandprev. I love how there are rules of sentence construction and ways to regularly understand what breaking each standard grammar rule means and aughhhh man i just love languages in general but the tumblr-lect (for lack of a better word) is so fascinating on a differenr scale. Its cool to me idk how else to put it

#im trying to do linguistics but im tired please be kind#tumblr#tumblr things#Tumblr culture#tumblr memes#small talk#linguistics

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

the sexual tension between me and sense relation taxonomies

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Similarities between Toki Pona and Lojban

Toki Pona and Lojban are two engineered constructed languages with speaking communities and very different goals. Toki Pona is a minimalist language based on simplifying your thoughts to fit the vocabulary of 140 words. Its grammar is similarly minimalistic. It has a simple sentence structure, not many particles and no affixes at all. Lojban is a logical language, one designed to express logical statements in its grammar and lack structural ambiguity. It is not at all minimalist, having over 3.5 times more particles than Toki Pona has words in total. It has particles for just about any grammatical function or marking you can think of.

So you may be surprised to learn that, having learned both languages, I consider them to be strikingly similar. They both have traits in common that English lacks for what I think are similar reasons.

Overall character

These are the big picture similarities. They are the cause of the specific similarities discussed later.

One class of root words

Both languages throw root words into one class, with usage determining their interpretation as a noun, verb or modifier. Both achieve this slightly differently.

Toki Pona's contentives

Most Toki Pona words cover broad semantic categories and have interpretations as nouns, verbs and modifiers relating to these categories in some way. For example, the definition of "moku" is:

eat, drink, consume, swallow, ingest; food, edible thing

These all relate to food and eating in some way. A very frequently cited example of Toki Pona's ambiguity is "mi moku" meaning "I eat" or "I am food", as Toki Pona doesn't have a copula. Note that it's not possible to predict how the meaning of a word changes between noun and verb usage and this must be memorised with each word.

Lojban's verbs

Lojban's only class of root word is verbs. These are defined in an unusual way, resembling sentences with blank spots given numbered Xs for nouns. For example, klama means:

x1 goes to x2 from x3 by route x4 with means/vehicle x5

"klama" is about as complex as verbs get, having 5 blank spots (arguments). Most have fewer than this! The blank spots are how Lojban creates nouns. The articles (lo/le) in Lojban select the first place of a verb and turn it into a noun. This avoids the need to memorise unpredictable changes in meaning for different words. For example, "lo citka" can only ever mean "an eater", it cannot mean "a food", which would be "lo cidja".

Concepts that are nouns in English are verbs in Lojban that include their copula. For example "cidja" means:

x1 is food for x2

This is as much as a verb to Lojban's grammar as the entire rest of its root word dictionary. The exact same grammar that works with "klama" works with "cidja". In other words, Lojban makes no distinction between being and doing. This also means that while Lojban does have a copula, it is barely ever used. Verbs contain "to be" in their definition.

Greedy phrases

In English you mostly know where a noun phrase ends because a lexically defined noun appears at the end of a string of lexically defined adjectives. Context and word order alone are usually sufficient to know how an English sentence is structured. Toki Pona and Lojban both take a different approach, because zero-deriving modifiers from contentives and verbs means that phrases are "greedy", they keep expanding unless explicitly separated.

Toki Pona phrases

Modifier phrases are the main way that Toki Pona stays expressive with only 140 words. Toki Pona has noun-modifier order. "jan pona" literally means "person good" but actually translates as "good person", since English is an adjective-noun language. You can keep adding root words onto phrases indefinitely and every following word modifies the whole phrase to its left:

small red car tomo tawa lili loje ((room move) small) red

Lojban tanru

Lojban's "tanru" are phrases just like Toki Pona's, where one word modifies another through juxtaposition. Lojban's order is backwards from Toki Pona, with the verb determining the place structure (and therefore most of the meaning) occurring last rather than first. However, Lojban still groups modifiers to the left. Just like in Toki Pona, root words can be added onto the end indefinitely since all are in the same category and they cannot, on their own, indicate the end of a noun phrase or start of a predicate.

intensely-red type of car kandi xunre karce ((intense) red) car

Keeping open question words in place

English fronts question words. This means that when asking a question, the syntax of the sentence is shuffled in some way that brings the wh-word to the start of the sentence. "You want what?" becomes "What do you want?". This is not the case in Toki Pona or Lojban, which prefer to keep question words unmoved.

Toki Pona's seme

The question word in Toki Pona is "seme" and it can go in the noun or verb positions of a sentence.

This is/does what? ni li seme?

This is good for who/what? ni li pona tawa seme?

Lojban's ma and mo

Lojban has different question words for every possible type of question. It has many more than just "ma" and "mo" which are noun and verb questions respectively. But those are the question words that most directly correspond with "seme" and just like it, don't require any change in word order.

This is/does what? .i ti mo

This is good for who/what? .i ti xamgu ma

Word order

Both Toki Pona and Lojban are similar to each other but also English in word order. Toki Pona has subject-verb-object word order and also tends to move preposition phrases to the end of sentences. While Lojban's word order is flexible, it defaults to a very Englishy order of putting the verb second, after a single noun and then putting all other nouns after the verb.

I give a book to you at the library.

mi pana e lipu, tawa sina, lon tomo lipu. I give a book, to you, at building book.

.i mi dunda lo cukta do bu'u le ckusro I give a book you at the library.

Specific similarities

As a result of the similarities in overall character, Lojban and Toki Pona have some very similar grammar.

Predicate markers

English doesn't have a predicate marker because it doesn't need one, not usually anyway. A predicate marker tells you where the verb in a sentence starts. This seemed like such an obviously artificial feature to me (having only seen it in Toki Pona and Lojban) that I assumed it was something that only existed in conlangs for a good while. I've since learned that Tok Pisin has a predicate marker. Natural languages are always stranger than I expect!

Toki Pona's li

The word "li" in Toki Pona separates third-person subjects from their predicates. It is essential to Toki Pona's grammar to allow for speakers to stop adding description to the subject and start the verb.

A big cat wants a fish. soweli suli li wile e kala.

Toki Pona allows for a subject to have multiple predicates attached to it by repeating "li".

A hunter sells food and goes to a house. jan alasa li esun e moku li kama, tawa tomo.

Lojban's cu

The word "cu" in Lojban terminates any nouns before the predicate of a sentence or clause. This is very similar to "li" and when Toki Pona speakers learn Lojban, it's very useful to be able to say "remember 'li'? it works like that".

A fish eats a person. .i lo finpe cu citka lo prenu

However, it is never actually obligatory in Lojban. It is usually used when the noun before the verb is one that uses an article, as opposed to a single-word pronoun. This is because pronouns self-terminate and don't start a greedy tanru phrase.

I run. .i mi bajra

Lojban only permits one "cu" per clause. This is a very helpful rule for certain deeply-nested sentence structures. Attaching multiple predicates to a single subject is still possible, but requires conjunctions.

A hunter sells a food and goes to a house. .i lo kalte cu vecnu lo cidja gi'e klama lo zdani

Phrase bracket particles

The default way that both languages group together modifiers in phrases means that it's impossible for multi-word phrases on the right to modify single words to the left. A phrase with the structure "A B C D" will always group together as "((A B) C) D" when what you want may be "(A B) (C D)". Both languages have words for this exact purpose of regrouping modifiers, a type of particle that has no direct counterpart in English.

Toki Pona's pi

Toki Pona's particle "pi" is used to override Toki Pona's default left grouping. An example is "tomo telo nasa", which translates to "crazy restroom" because "tomo telo" groups together and is finally modified by "nasa".

crazy restroom (tomo telo) nasa (room water) crazy

Putting a "pi" after "tomo" allows for "telo nasa" (alcohol) to modify "tomo", creating the meaning of "bar". These two very different meanings are only distinguished by the grouping of modifiers.

bar tomo pi (telo nasa) room (water crazy)

Using multiple "pi" in one phrase is ambiguous and considered bad style. It is unclear whether both pi phrases apply equally to the head of the phrase (flat pi) or the second pi phrase applies only to the contents of the pi phrase it follows (nested pi). The example given in sona pona is "lipu pi sona mute pi toki Inli". Is it a book of much knowledge of English, or a book of much knowledge and English?

Lojban's ke-ke'e

Lojban's particle "ke" does pretty much the exact same thing as "pi", but appears in opposite situations from "pi" due to the opposite word order of tanru compared to Toki Pona phrases.

catcher of big dogs barda gerku kavbu (big dog) catcher

The meaning of the phrase without pi in Toki Pona has to use "ke" to get the brackets on the right of the phrase.

a catcher of dogs, who is big barda ke gerku kavbu big (dog catcher)

Unlike Toki Pona, mulitple "ke" particles unambiguously nest into each other. Conjunctions are needed to achieve the "flat pi" meaning from Toki Pona.

small school for girls which is beautiful melbi ke cmalu ke nixli ckule pretty (small (girl school))

Unlike Toki Pona, a terminating particle "ke'e" closes the opening bracket created by "ke". Sometimes, the entire "ke-ke'e" structure may be replaced with "bo" as this marks a gap between two verbs to be interpreted as grouping together first before the usual left-grouping rule is applied.

small catcher of big dogs cmalu ke barda gerku ke'e kavbu cmalu barda bo gerku kavbu small (big dog) catcher

Analysis

Toki Pona is vague, not ambiguous

With a few small exceptions such as preverbs, prepositions and nested pi, the structure of a Toki Pona sentence is usually not ambiguous because of very un-englishy particles tagging parts of sentences such as "li" and "e". Most of Toki Pona's multiple interpretations come from its words covering board "semantic spaces", fuzzy clouds of meaning that are clarified through the addition of modifiers and context.

Toki Pona and Lojban both solve ambiguity in similar ways

Both being SVO isolating languages with greedy phrases, both languages use similar very obvious solutions for terminating phrases. Lojban has terminators, articles, prepositions and the predicate marker "cu". Toki Pona has "en", "li", "e" and prepositions marking the starts of phrases in sentences. The biggest overlap is predicate marking, but both languages also have particles exclusively for regrouping modifiers.

#constructed language#constructed languagse#Lojban#Toki Pona#Linguistics#Syntax#Grammar#Conlangs#Conlang#Logical languages#infodump

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psychological transition ; Linguistic transition

Psychological transition: when your mind adapts to a new gender that was unusual of you before.

This may include finding out that you experience your natally assigned gender or sex, after questioning or feeling a void about it, not just transitioning to the other side or beyond a specific AGAB.

Linguistic transition: going through a different form of experiencing gender language, typically in grammar, syntax, lexical metaphor, or semantics

The most known forms of linguistic transition are name change and pronoun change, but can be beyond those things. Overall this may also include the journey of finding out you possess/own/have finally the imposed pronoun or initially registred name after all.

The psychological type is often associated with social transition, in which your social circle starts to refer to you as a certain gender and that helps you navigate with such gender, exploring a gender life. However, that is psychosocial transition, because you can transition psychologically (mentally, thymically/thymally, phrenically, psychically/psychally, thymopsychically, mindfully/phrenetically, or spiritually/religiously, in uncommon definitions) without externalizing (verbalizing) or telling anyone else (extrapersonally/exopersonally/ectopersonally), which typically means you're closeted about it, but you don't necessarily need to out yourself to someone just because you found out something different. Also you can alter everything outside and only name it rightly in your psyche/mind/thymus after it. imagine crossdreaming.

The linguistic type is not something exclusive to transnominal/crossnominal or people with name dysphoria (sofrimento/tristesse or disconnect/incongruence), this may or may not be a form of name nonconformity. Another form of linguistic transition is transitioning through grammatical objects, animacy/inanimacy, grammatical persons, or isochronally (tonally/accentually/syllabically/in a mora way), for example, depending on the language there are multiple ways to do this. This could extend to any label, if you think about it lexically/lingually.

More importantly (note): these are describing acts, not definers/identifiers.

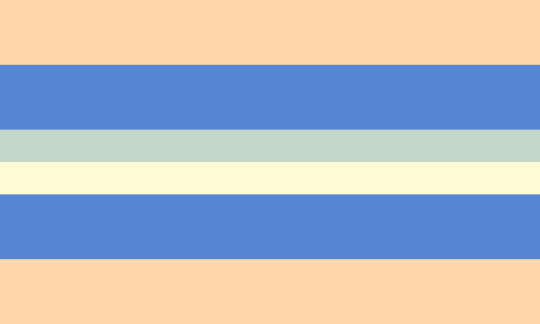

#linguistic transition#name change#psychological transition#transitioning#gender#pronoun ideas#pride flags#mod a-p#mogai pride flags#beyond liomoqai#qai coining#liomogai safe#liom term#mind#pronouns#names#new#psyche

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semasiology (from Greek: σημασία, semasia, "signification") is a discipline of linguistics concerned with the question "what does the word X mean?". It studies the meaning of words regardless how they are pronounced. It is the opposite of onomasiology, a branch of lexicology that starts with a concept or object and asks for its name, i.e., "how do you express X?" whereas semasiology starts with a word and asks for its meanings. The exact meaning of semasiology is somewhat obscure. It is often used as a synonym of semantics (the study of the meaning of words, phrases, and longer forms of expression). However, semasiology is also sometimes considered part of lexical semantics, a narrow subfield of lexicology (the study of words) and semantics. The term was first used in German by Christian Karl Reisig in 1825 in his work, [Lectures on Latin Linguistics] (German: Vorlesungen über lateinische Sprachwissenschaft), and was used in English by 1847. Semantics replaced it in its original meaning, beginning in 1893.

Wikipedia

#quote#language#linguistics#Christian Karl Reisig#semasiology#semantics#meaning#lexicology#onomasiology#words

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

some cultural curiosities implied by Francis Ratte's reconstruction of Proto-Japo-Koreanic (a clearly superior term to Ratte's own "Proto-Korean-Japanese", by the way)—

both branches of Japo-Koreanic appear to have suppressed the original (unreconstructed & perhaps unreconstructible) pJK word for "to die" in favour of euphemisms. Japanese shinu continues pJK *ti-na "pass by" (~ Korean jina "to pass"), and Korean jug-da continues pJK. *cuk- "exhausted" (~ Japanese tsukusu "to exhaust, use up")

both branches performed some strange semantic switcheroos with the two reconstructed pJK words for canids. Ratte reconstructs pJK *kituj "wolf; wild canid" as the ancestor of Korean ili "wolf" (< pre-Middle Korean *ílhuy, earlier *híluy) and Japanese kitsune "fox" (< Old Japanese kitu-ne, with -ne analysed as a diminutive suffix), and *jenu "dog" (domesticated canid?) as the ancestor of Korean yeou "fox" (< pre-MK *yen-sok) and Japanese inu "dog" (OJ opokami "wolf", whence Japanese ōkami, is very clearly an euphemism—Ratte glosses it as "great biter")

Ratte's reconstructions make it fairly clear Proto-Japo-Koreanic originated somewhere in continental Asia before making its way to its postulated homeland near the Bay of Bohai. most of the marine vocabulary he reconstructs for pJK appears adapted from earlier lexical strata—he derives pJK *wat-a "sea" from *wat- "to cross over; to change hands", giving "that which is crossed over" as an alternate gloss for the former, and speculates pJK *sima-a "island" might've originally meant "enclosure" (cf. OJ sime- "closes it off", from *sim-). I'd also question his gloss of pJK *muta as "shore", given that Middle Korean mwut-h and Old Japanese muta both primarily mean "earth". the semantic shift from "earth" to "shore" is apparently specific to Korean; compare the shift of Middle Korean *yém "mountain" (cognate to Japanese yama, attested in compounds) to modern Korean yem "rocks sticking out of water" after the word became displaced in its original sense by the Sinitic borrowing san

the absolute latest date for the disintegration of Proto-Japo-Koreanic hovers around 1,500 BCE, when wet rice agriculture was introduced to East Asia (Japonic and Koreanic share vocabulary related to the cultivation of millet and dry rice, but not wet rice). this could make the latest stage of the language contemporaneous with the Shang dynasty (c. 1,600 – 1,046 BCE), the earliest Chinese dynasty whose existence is supported by archaeological evidence. neat! idk shit about the cultural landscape of Bronze Age East Asia, so I'll avoid making any claims on potential material carriers of Proto-Japo-Koreanic

for comparison, 1,500 BCE is also when Wikipedia estimates Pre-Proto-Slavic began to diverge from Proto-Balto-Slavic—completely nuts to think Japanese and Korean could be about as distant from one another as Lithuanian is from Russian (though do note Wikipedia gives no source for its dating of Pre-Proto-Slavic)

Ratte speculates speakers of Proto-Japo-Koreanic could've borrowed their word for "wheat", *morki (whence Japanese mugi, Korean mil), from Old Chinese *mêrˤêk. on the other hand, Starostin (1990) compared (presumably in the context of Macro-Altaic) the word's Japanese and Korean reflexes to Proto-Tungusic *murgi "barley"—and, honestly, the similarities between *murgi and *morki are rather startling, assuming Starostin's reconstruction of the Proto-Tungusic word is valid. who can say...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese illustrates the complex interaction between male social/political dominance and control of language use. It manifests not only the three ways patriarchal language infiltrates our minds and the ways we talk (or are permitted to talk) or are talked about by men, but also provides instances of women's defiance of PUD [Patriarchal Universe of Discourse] rules. When men name the world of their perceptions, they also name the place of women in that world; these names lexicalize men's concepts and form semantic sets within a culture's vocabulary. When men control the social and grammatical rules of a language and have mandated their dialect as the standard, they define what women are allowed to say and the way in which they must say it. The "place" of a woman in a man's world isn't only reflected in certain sets of words in the language's vocabulary but is also marked in her speech by specific suffixes. Japanese women aren't utterly silent, however, and have words for describing their own experiences, including derogatory terms for men.

In a 1988 Weekend Edition, National Public Radio (NPR) did a segment called "Japanese Women's Language." A man's voice introduced the segment as "a story about sexism, although most people in the country we're about to visit wouldn't call it that." Patronizingly acknowledging that, "of course, the United States has its share of sexism," he went on with his ethnocentric description of "sexism" in Japan:

now imagine a culture that forbids women most of the time to speak the same language as men, a society where women actually have to use different words than men do to say the same thing, or else they'll be shunned.

Men's subjugation of women in Japan goes back at least 1,000 years, to a time when women were forbidden to speak to men. In the 1930s, the Japanese government issued edicts warning women not to use words reserved to men, and the resulting differentiations remain in force, if not the edicts themselves (NPR). The significant adjectives that distinguish onna kotaba, 'women's words', from the male dialect are 'soft' and 'harsh', the equivalents of English 'weak' and 'forceful'. One example of the pressure on women to speak softly and submissively, if they speak at all, is the custom of hiring elevator "girls" in Japanese department stores.

According to the NPR report, women hired as elevator "girls" must be "pretty, young, and very, very feminine." One of the behaviors that conveys onna-rashisa (the stereotype of femininity) is the ability to speak women's "language" correctly, and this aspect of the elevator operator's job performance is closely monitored. They are expected to talk in "perfect women's language," and "never slip and use a masculine word." Their fluency in the linguistic display of submissiveness is insured by one-half hour of mandatory daily practice, during which any "unfeminine" pronunciations are corrected. In order for a woman, any woman, to be perceived as "nice," she must speak "correct women's language" (NPR). Women who don't speak the submissive dialect men assign to them don't get jobs.

R. Lakoff (1975) and Mary Ritchie Key (1975) both noted that the sentences of English-speaking women are likely to be longer and wordier than those of men, and the same apparently holds true for Japanese. A man might be able to say, "Open the window!" but a Japanese woman, in order to get the same thing done, would have to say, "Please open the window a little bit, if you don't mind!" The result is that a woman's sentence has only one or two words in common with a comparable male utterance (NPR) and is much longer. Not surprisingly, Japanese women's dialect is perceived as more subservient and tentative than men's, because the women must use submissive, self-effacing phrases equivalent to the tag-questions that Robin Lakoff (1975) associated with women's speech in English. These phrases translate into English as "do you think," "I can't be sure," and "will it be," and their use in commonplace statements means that Japanese women say an average of 20% more words than men to describe the same thing. In Japanese, it is impossible for a woman to speak informally and assertively at the same time (NPR).

-Julia Penelope, Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of the Fathers’ Tongues

#julia penelope#japanese language#female oppression#patriarchy#women’s language#perhaps women are stereotyped as being more talkative because men force them to do so#linguistics

34 notes

·

View notes