#and police brutality is bad but also good sometimes. if jim does it its good. unless he does it in a bad way. the morals are arbitrary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

im thinking about how they made oswald such a stereotypical gay man. like really old stereotypes that people don't even seem to perpetuate the modern day. but gotham had to. they went ok lets give this fag an overbearing mother and absent father. oh and make him overly neurotic. oh and also let's pull the 1950s trope of the homicidal homosexual. and so they did and then the entire series is like "let's see how much we can make this gay man suffer." there's not really a Point to this post i just find it interesting bc it stood out to me so much and ive talked to my friends about it but no one else online seems to have mentioned it

which is crazy bc the only thing you could do to make him any more stereotypically gay would be to make him extra flamboyant and really into theater and do drugs and listen to amy winehouse.... but they had to save those stereotypes for the other gay lmao

#the homicidal part is fine bc everyone in this show is the killer#and im also a gay stereotype ig bc i think thats sexy#but like. is no one else picking up on the classic stereotypes#of him being such a momma's boy#and oh the neurosis#look i love gotham. its so camp. but they would have benefited so much from more diversity in the cast and writers room#like imagine gotham but gay people are allowed to be gay and women are allowed to exist without being absorbed into the jim vortex#and if less than 99% of the cast were white. and if they didnt have to bend over backward ti avoid politics to the point of absurdity#like yeag in gotham crime exists because everyone is either evil or insane. and people are only poor because theyre stupid and need#guidance from some random white woman to tell them that stealing from each other is not productive actually. and no one has ever thought of#this before#and police brutality is bad but also good sometimes. if jim does it its good. unless he does it in a bad way. the morals are arbitrary#what im saying is gotham is insane#its an insane tv show full of horrible stereotypes and nonsensical writing#and yet its soooooooo fucking good#its so fitting that its on tubi bc thats exactly where a show like gotham belongs#right up there with such classics as shark side of the moon and zombie shark and other various nonsense#like again to be clear i fucking love gotha#gotham*#and its so good it made me start reading comics#which i formerly had no interest in#like im fully in my gotham obsession era#i just also yell at the screen a lot while watching#i would not be criticizing a show this much if i did not ultimately enjoy it and think it is worth watching

1 note

·

View note

Text

@superohclair oh god okay please know these are all just incoherent ramblings so like, idk, please feel free to add on or ignore me if im just wildly off base but this is a bad summary of what ive been thinking about and also my first titans/batman meta?? (also, hi!)

okay so for the disclaimer round: I am not an actual cultural studies major, nor do I have an extensive background in looking at the police/military industrial complex in media. also my comics knowledge is pretty shaky and im a big noob(I recently got into titans, and before that was pretty ignorant of the dceu besides batman) so I’ll kind of focus in on the show and stuff im more familiar with and apologize in advance?. basically im just a semi-educated idiot with Opinions, anyone with more knowledge/expertise please jump in! this is literally just the bullshit I spat out incoherently off the top of my head. did i mention im a comics noob? because im a comics noob.

so on a general level, I think we can all agree that batman as a cultural force is somewhat on the conservative side, if not simply due to its age and commercial positioning in American culture. there are a lot of challenges and nuances to that and it’s definitely expanding and changing as DC tries to position itself in the way that will...make the most money, but all you have to do is take a gander through the different iterations of the stories in the comics and it’ll smack you in the fucking face. like compare the first iteration of Jason keeping kids out of drugs to the titans version and you’ve got to at least chuckle. at the end of the day, this is a story about a (white male) billionaire who fights crime.

to be fair, I’d argue the romanticization of the police isn’t as aggressive as it could be—they are most often presented as corrupt and incompetent. However, considering the main cop characters depicted like Jim Gordon, the guys in Gotham (it’s been a while since I saw it, sorry) are often the romanticized “good few” (and often or almost always white cis/het men), that’s on pretty shaky ground. I don’t have the background in the comics strong enough to make specific arguments, so I’ll cede the point to someone who does and disagrees, but having recently watched a show that deals excellently with police incompetence, racism, and brutality (7 Seconds on Netflix), I feel at the very least something is deeply missing. like, analysis of race wrt police brutality in any aspect at all whatsoever.

I think it can be compellingly read that batman does heavily play into the military/police industrial complex due to its takes on violence—just play the Arkham games for more than an hour and you’ll know what I mean. to be a little less vague, even though batman as a franchise valorizes “psychiatric treatment” and “nonviolence,” the entire game seems pretty aware it characterizes treatment as a madhouse and nonviolence as breaking someone’s back or neck magically without killing them because you’re a “good guy.” while it is definitely subversive that the franchise even considers these elements at all, they don’t always do a fantastic job living up to them.

and then when you consider the fetishization of tools of violence both in canon and in the fandom, it gets worse. same with prisons—if anything it dehumanizes people in prisons even more than like, cop shows in general, which is pretty impressive(ly bad). like there’s just no nuance afforded and arkham is generally glamorized. the fact that one of the inmates is a crocodile assassin, I will admit, does not help. im not really sure how to mitigate that when, again, one of the inmates is a crocodile assassin, but I think my point still stands. fuck you, killer croc. (im just kidding unfuck him or whatever)

not to take this on a Jason Todd tangent but I was thinking about it this afternoon and again when thinking about that cop scene again and in many ways he does serve as a challenge to both batman’s ideology as well as the ideology of the franchise in general. his depiction is always a bit of a sticking point and it’s always fascinating to me to see how any given adaptation handles it. like Jason’s “”street”” origin has become inseparable from his characterization as an angry, brash, violent kid, and that in itself reflects a whole host of cultural stereotypes that I might argue occasionally/often dip into racialized tropes (like just imagine if he wasn’t white, ok). red hood (a play on robin hood and the outlaws, as I just realized...today) is in my exposure/experience mostly depicted as a villain, but he challenges batman’s no-kill philosophy both on an ethical and practical level. every time the joker escapes he kills a whole score more of innocent people, let alone the other rogues—is it truly ethical to let him live or avoid killing him for the cost of one life and let others die?

moreover, batman’s ““blind”” faith in the justice system (prisons, publicly-funded asylum prisons, courts) is conveniently elided—the story usually ends when he drops bad guy of the day off at arkham or ties up the bad guys and lets the police come etc etc. part of this is obviously bc car chases are more cinematic than dry court procedurals, but there is an alternate universe where bruce wayne never becomes batman and instead advocates for the arkham warden to be replaced with someone competent and the system overhauled, or in programs encouraging a more diverse and educated police force, or even into social welfare programs. (I am vaguely aware this is sometimes/often part of canon, but I don’t think it’s fair to say it’s the main focus. and again, I get it’s not nearly as cinematic).

overall, I think the most frustrating thing about the batman franchise or at least what I’ve seen or read of it is that while it does attempt to deal with corruption and injustice at all levels of the criminal justice system/government, it does so either by treating it as “just how life is” or having Dick or Jim Gordon or whoever the fuckjust wipe it out by “eliminating the dirty cops,” completely ignoring the non-fantasy ways these problems are dealt with in real life. it just isn’t realistic. instead of putting restrictions on police violence or educating cops on how to use their weapons or putting work into eradicating the culture of racism and prejudice or god basically anything it’s just all cinematized into the “good few” triumphing over the bad...somehow. its always unsatisfying and ultimately feels like lip service to me, personally.

this also dovetails with the very frustrating way mental health/”insanity” or “madness” is dealt with in canon, very typical of mainstream fiction. like for example:“madness is like gravity, all it takes is a little push.” yikes, if by ‘push’ you mean significant life stressors, genetic load, and environemntal influences, then sure. challenge any dudebro joker fanboy to explain exactly what combination of DSM disorders the joker has to explain his “””insanity””” and see what happens. (these are, in fact, my plans for this Friday evening. im a hit at parties).

anyway I do really want to wax poetic about that cop scene in 1x06 so im gonna do just that! honestly when I first saw that I immediately sat up like I’d sat on a fucking tack, my cultural studies senses were tingling. the whole “fuck batman” ethos of the show had already been interesting to me, esp in s1, when bruce was basically standing in for the baby boomers and dick being our millennial/GenX hero. I do think dick was explicitly intended to appeal to a millennial audience and embody the millennial ethos. By that logic, the tension between dick and Jason immediately struck me as allegorical (Jason constantly commenting on dick being old, outdated, using slang dick doesn’t understand and generally being full of youthful obnoxious fistbumping energy).

Even if subconsciously on the part of the writers, jason’s over-aggressive energy can be read as a commentary on genZ—seen by mainstream millennial/GenX audiences as taking things too far. Like, the cops in 1x06 could have been Nick Zucco’s hired men or idk pretty much anyone, yet they explicitly chose cops and even had Jason explain why he deliberately went after them for being cops so dick (cop) could judge him for it. his rationale? he was beaten up by cops on the street, so he’s returning the favor. he doesn’t have the focused “righteous” rage of batman or dick/nightwing towards valid targets, he just has rage at the world and specifically the system—framed here as unacceptable or fanatical. as if like, dressing up like a bat and punching people at night is, um, totally normal and uncontroversial.

on a slightly wider scope, the show seems to internally struggle with its own progressive ethos—on the one hand, they hire the wildly talented chellah man, but on the other hand they will likely kill him off soon. or they cast anna diop, drawing wrath from the loudly racist underbelly of fandom, but sideline her. perhaps it’s a genuine struggle, perhaps they simply don’t want to alienate the bigots in the fanbase, but the issue of cops stuck out to me when I was watching as an social issue where they explicitly came down on one side over the other. jason’s characterization is, I admit and appreciate, still nuanced, but I’d argue that’s literally just bc he’s a white guy and a fan favorite. cast an actor of color as Jason and see how fast fandom and the writer’s room turns on him.

anyway i don’t really have the place to speak about what an explicitly nonwhite!cop!dick grayson would look like, but I do think it would be a fascinating and exciting place to start in exploring and correcting the kind of vague and nebulous complaints i raise above. (edit: i should have made more clear, i mean in the show, which hasn’t dealt with dick’s heritage afaik). also, there’s something to be said about the cop vs detective thing but I don’t really have the brain juice or expertise to say it? anyway if you got this far i hope it was at least interesting and again pls jump in id love to hear other people’s takes!!

tldr i took two (2) cultural studies classes and have Opinions

#wow this was a hot fucking mess#i tried to be organized but my thoughts weren't coming out super well#again anyone interested please feel free to jump in or correct me at any place you feel like#i die on the ''jason todd would be treated horribly by fandom if he were a character of color' hill tho#i could go on about 1x06 until im blue in the face but that's the uhh overview. the executive summary.#dc titans#i need meta tags and shit for this show#god help me in too deep#finding the meta side of fandom was a GIFT tho i love this shit#so excited

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detroit dir. Kathryn Bigelow (2017)

I finally saw Detroit, the day of the Charlottesville Nazi march no less. I have very mixed feelings on the movie and they're only mixed because director Kathryn Bigelow is a really good filmmaker. People who were most wary of the film because it had a white writer were right to be so, because the script is absolutely the weakest link and writer Mark Boal, who also wrote the scripts for Bigelow's films The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, has penned a script that gets so much wrong, trampling all over moments of subtlety with clumsy dialogue and making minimal effort to deliver context. The film has a very clear three-part structure: the first is dedicated to the overarching outrage and frustration that led to the 1967 riots, the second shows the murders of three black men by the police at the Algiers motel that took place mid-riots, and the third focuses on the lack of justice provided by a biased and ineffectual legal system. But at every turn the writing, and sometimes the direction, undercuts its own message. Aside from some completely lazy title text accompanied by some very ugly animation, the first section does an absolutely terrible job of showing why black people in Detroit started rioting and even mostly privileges the perspective of the police. The final section is so bad you have a character screaming out "the system is rigged" in a courtroom as if the movie doesn't trust the audience to put the pieces together. And that's a real pity because these two weak sections bracket the strongest most effective part of the movie where Bigelow delves in to what exactly went down at the Algiers and where Boal for the most part (but unfortunately not completely) curbed his need of having characters broadcast the film’s intentions. This is the part of the movie that's earned the most criticism for the amount of violence, but it's a violence that feels earned in a way that the violence of the first section of the movie doesn't. This is Bigelow at her masterful best, juggling a large ensemble of characters so that their actions and motivations are clear. Despite the chaotic nature of the action, which involves about a dozen characters running in and out of various rooms, the geography of the place is never in doubt so that audiences are able to fully focus on the horror of the actions. It is by no means a perfect piece of cinema but it's by far the best part of a fractured film because it shows (without telling!) that there is absolutely no winning what the police call the "game", where they use brutality to get their suspects to confess, or indeed any way of winning when it comes to black men dealing with the police at large. One of the gifts of the large ensemble is watching as all the black men take different approaches to trying to survive the night and the absolute desolation of watching as every single one loses. Even the ones who live come away completely destroyed by what they've seen and what they needed to do to survive. Will Poulter, playing a racist cop, has been met with the most praise and though he's very good among my favourites were John Boyega as a security guard who decides the best approach is to act deferential. It's not a great role, again the writing lets him down, but he has such a commanding presence that he's a pleasure to watch on screen. Algee Smith as an ambitious young singer and Jacob Latimore as his friend and roadie are also standouts. I've heard no one praise Anthony Mackie but he has one of the best moments in the film. Sitting in his room with two young white girls they hear the police invading the motel he starts coaching them on what to do and how to act and without further explanation you can tell from the exhaustion and fear in his voice that he's been in this situation before. It's a quiet well articulated moment of the kind the film could have used more of. Also to briefly bring up the two white girls who are also brutalized by the police: Hannah Murray has the biggest part between the two of them and she is unfortunately awful. I'm honestly so disappointed because though the role was small it covered a lot of complexities I've never seen depicted before on screen: the way white women use black men and black culture as a way of being transgressive, the way white women are used as an excuse for white men to lash out against black men, the way that even if they are privileged in some ways they can be victims of sexual harassment and abuse, and the way in which despite these things they can retreat back into the privilege of their whiteness. A lot of complexities going on that are ruined by Murray's atrocious performance. I wish Bigelow had chosen someone else. Some more scattered thoughts: I love it when directors reuse actors so I enjoyed seeing Anthony Mackie and also Jennifer Ehle, so great in Zero Dark Thirty, in a cameo! The production values on this were amazing and the costume design by Francine Jamison-Tanchuck, especially for the women, was gorgeous. I can never unthink of John Krasinski as Jim from The Office, and he was distracting as a smarmy police union lawyer. Samira Wiley also pops up for literally less than a minute, the role didn't require her having a lot to do but it seems like such a crime to have her do the work of a glorified extra. I wish I could recommend it because I am a huge fan of Bigelow but I just can't. The riots deserved a better movie and I believed Bigelow could do better so I'm disappointed that the resulting film was so uneven. Even though the time never dragged for me this only ever felt like a very solid first draft with hints of how much better it could have been. I'm not surprised it's flopping at the box office because a) it's not very good and b) who exactly is the audience for this? White racists won't touch a movie that address systematic racism by police and white people sympathetic to the film's message will have a difficult time sitting through a two and half hour uneven film filled with gruelling violence. By the time I walked out of Detroit to check the news a woman was dead and many more injured after a Neo-Nazi plowed his car into a crowd of peaceful protestors. It served as a painful real-world reminder that black audiences and other people of colour are already living everything Detroit has to say.

#Detroit#Kathryn Bigelow#2017#USA#Anthony Mackie#FYWFD reviews#Post 2000 series#Hannah Murray#Will Poulter#John Krasinski#jennifer ehle#samira wiley#John Boyega#Algee Smith#Jacob Latimore

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Weekend Warrior Home and Drive-In Edition July 24, 2020: THE RENTAL, MOST WANTED, YES GOD YES, AMULET, RETALIATION and more

Are we all having fun yet? Does the fun ever truly begin when you’re in the middle of a pandemic, and no one can seem to figure out how to get out of it? While I love New York’s Governor Cuomo and the amazing job he did getting us through the worst of it, he just doesn’t seem to know how to get movie theaters reopened, nor does he seem to care. I mean, they’ve had four months now to figure this out and New York City is already in Phase 4 (which was supposed to be the last phase of the reopening). It’s a real shame, because this has been a ridiculously hot summer and with none of the “cooling centers” from past summers being possible, it is brutal out there. Fortunately, there are a few decent movies this week to watch at home and some in the drive-ins that are popping up all over the country.

I gotta say that I’m particularly bummed that my favorite local theater, the Metrograph, won’t be opening any time soon, but starting Friday, they’ll be starting “Metrograph Live Screenings,” which will consist of the type of amazing programming the theater has gained a reputation for since opening four years ago. They are offering new “digital memberships” at $5 a month or $50 annually (about half the price of a normal membership) so that you can watch any of the movies being offered at home. The program begins on Friday with Claire Denis’ 2004 film, L’Intrus, which Metrograph Pictures picked up for release. That’s followed on Monday with St. Claire Bourne’s doc, Paul Robeson: Here I Stand. You can see the full list of screening times and dates (many with filmmaker introductions) on the Official Site, and this will be a good time for those who can’t get downtown to the coolest area in New York City to check out the Metrograph programming until they reopen. (Apparently, they’re working on a drive-in to open sometime in August. Wish I had a car.)

If nothing else, it’s safe to say that IFC is killing it this summer. The indie distributor stepped right up to the pandemic and said, “Hey, we’ll play in those drive-in theaters that have mostly been ignored and didn’t play our films for decades!” It has led to at least two big hits in the past few months.

This week, IFC releases the horror/thriller THE RENTAL (IFC Films), the directorial debut by Dave Franco. In it, brothers Charlie (Dan Stevens) and Josh (Jeremy Allen White) decide to take a weekend away with their significant others, Charlie’s wife Michelle (Allison Brie) and Josh’s girlfriend Mina (Sheila Vand), who also happens to be Charlie’s creative work partner. They have found a remote house to rent, but they’re immediately suspicious of the caretaker (Toby Huss), who they think may be spying on them. He’s also racist towards Mina’s Arab lineage.

The premise seems fairly simple and actually quite high concept, and there have been quite a few thrillers that played with the premise of a creepy landlord/caretaker, including last year’s The Intruder, directed by Deon Taylor, and a lesser known thriller called The Resident, starring Hillary Swank and Jeffrey Dean Morgan. Part of what makes The Rental different is that Franco co-wrote it with Joe Swanberg, so you know it’s going to be more of a character-based thriller than some kind of gorefest. Sure enough, this deals with the competitive nature between the brothers and the jealousy that arises when you have such a close working relationship with your brother’s girlfriend. It’s what happens between these two couples over the course of this vacation that makes you even more interested in their behavior after things start happening to them, but there’s a pretty major twist that happens just when you think you know where things may be going.

That’s all I really should say about the plot to avoid spoilers. Although the third act veers into the darker horror tropes we may have seen before, that’s also when it starts to get quite insane. Franco clearly shows he has the eye for the type of suspense and timing necessary for an effective thriller, and his cast, including wife Alison Brie, really deliver on all aspects of his script to deliver shocking moments that will keep you invested.

In some ways, The Rental might be the most obviously accessible movie of the weekend, and since it will be playing in drive-ins (and maybe a few still-open theaters?), it probably is worth seeing that way i.e. with others, although it will also be available via digital download, of course.

Another “Featured Flick” this week -- and I’m guessing this is one you won’t be reading about anywhere else -- is Daniel Roby’s MOST WANTED (Saban FIlms), a real-life crime-thriller starring Josh Hartnett as Globe and Mail journalist, Victor Malarek, who discovered that a French-Canadian junkie named Daniel Léger (Antoine-Olivier Pilon) had been sentenced to 100 years in a Thailand prison for drug trafficking in 1989. As Daniel attempts to survive the violent conditions of the Thai jail, Victor tries to uncover the crooked practices by the Canadian federal police to get Daniel imprisoned for their own means.

This is one of two Saban Films releases that really surprised me, maybe because I’ve gotten so used to them releasing so much action and genre schlock meant mainly for VOD, usually starring fairly big-name action stars from the past, usually not doing their best work. Most Wanted is a far more serious crime-drama that tells an absolutely amazing story from North America’s famed war on drugs from the ‘80s. First, we meet Antoine-Olivier Pilon’s Daniel, a lowlife junkie who is trying to find a place to live and a job, something he finds when he gets into business with Jim Gaffigan’s Glenn Picker, a complete low-life in every sense of the word. It’s funny, because when Gaffigan’s character is introduced, you’re immediately reminded of the famous “Sister Christian” in PT Anderson’s Boogie Nights, and as we watch Picker completely humiliate and then betray Daniel, you realize that we might be seeing one of Gaffigan’s best performances to date.

What keeps Most Wanted interesting is that it tells the story on a number of concurrent storylines, ignoring the fact that one of the threads might be taking place years before the other. Through this method, we see how Daniel begins working with Glenn, while also seeing Victor’s investigation, as well as the sting operation being perpetrated by the Canadian feds, as represented by the always great Stephen McHattie. (McHattie’s appearance is also a telltale sign that this is indeed a Canadian production, as is the role played by author and filmmaker Don McKellar.) I’ve always feltHarnett was a really underrated actor especially as he got into his 30s and started doing more mature roles, and while his reporter character may not always be the central focus of the story, his attempt to get his editor to respect his work is something far too familiar to far too many writers. One also can’t sleep on the fantastic performance by Antoine-Olivier Pilon, who really holds the film together by starting out as a scumbag almost as bad as Picker but through his troubles to survive in Thai jail, we start to become really invested in his story. (The only character who doesn’t get nearly as fulfilling a story arc is Amanda Crew as Victor’s wife Anna who gives birth just as he gets involved in this major story.)

I wasn’t at all familiar with Daniel Roby’s previous work but the way he broke this story down in a way that keeps it interesting, regardless of which story you’re following, makes Most Wanted as good or better than similar films by far more experienced and respected filmmakers. (For some reason, it made me think of both The Departed and Black Mass, both movies about Whitey Bulger, although Daniel’s story is obviously very different.)

Okay, let’s get into a trio of religious-tinged offerings…

Natalia Dyer from Stranger Things stars in YES, GOD, YES (Vertical Entertainment), the semi-autobiographical directorial debut by Obvious Child co-writer Karen Maine (expanded from an earlier short), which will open via virtual cinemas this Friday as well as at a few drive-ins, and then it will be available via VOD and digital download on Tuesday, July 28. The coming-of-age comedy debuted at last year’s SXSW Film Festival and won a Special Jury Prize for its ensemble cast. Dyer plays sixteen-year-old Alice, a good Midwestern Catholic teenager, who has a sexual awakening after a racy AOL chat. Wracked by guilt, Alice attends a religious retreat camp where the cute football player (Wolfgang Novogratz) catches her eye, but she constantly feels pressure to quell her masturbatory urges.

I’m not sure I really knew what to expect from Ms. Maine’s feature film debut as a director. I certainly didn’t expect to enjoy this movie as much as I did, nor did I think I would relate to Dyer’s character as much as I did -- I’ve never been a teen girl, nor have I ever been Catholic, and by the early ‘00s, I was probably closer to the age that Maine is now versus being a teenager discovering her sexuality. In fact, I probably was expecting something closer to the Mandy Moore comedy Saved!, which was definitely more about religion than one character’s sexual journey.

Either way, I went into Yes, God, Yes already realizing what a huge fan I am of coming-of-age stories, and while there were certainly that seemed familiar to other films, such as Alice’s inadvertent AIM with an online pervert early in the film. Even so, Maine did enough with the character of Alice to keep it feeling original with the humor being subdued while definitely more on the R-rated side of things. On top of that, Dyer was quite brilliant in the role, just a real break-through in a similar way as Kaitlyn Dever in Book Smart last year. (Granted, I’m so behind on Stranger Things, I don’t think I’ve even gotten to Dyer’s season.) The only other familiar face is Timothy Simons from Veep as the super-judgmental (and kinda pervy) priest who Alice has to turn to when confessing her sins. (A big part of the story involves a rumor started about Alice and a sex act she committed on a fellow student that keeps coming up.)

Yes, God, Yes proves to be quite a striking dramedy that I hope more people will check out. I worry that because this may have been covered out of last year’s SXSW, it might not get the new and updated attention it deserves. Certainly, I was pleasantly surprised with what Maine and Dyer did with a genre that still has a lot to tell us about growing up and discovering oneself. (You can find out where you can rent the movie digitally over on the Official Site.)

Another horror movie that premiered at this year’s Sundance is AMULET (Magnet), the directorial debut by British actor Romola Garai, who also wrote the screenplay. It stars Romanian actor Alec Secareanu as Tomaz, a former soldier who is offered a place to stay in a dilapidated house in London with a young woman named Magda (Carla Juri from Blade Runner 2049) and her ill and dying mother. As Tomaz starts to fall for Magda, he discovers there are sinister forces afoot in the house with Magda’s mother upstairs being at their core.

I was kind of interested in this one, not just because it being Garai’s first feature as a filmmaker but also just because Sundance has such a strong pedigree for midnight movies, probably culminating in the premiere of Ari Aster’s Hereditary there a few years back. It feels like ever since then, there are many movies trying to follow in that movie’s footsteps, and while this was a very different movie from the recent Relic, it had its own set of issues.

The main issue with Amulet is that it deliberately sets itself up with a confusing narrative where we see Tomaz in the present day and in the past concurrently, so it’s very likely you won’t know what you’re watching for a good 20 minutes or so. Once Tomaz gets to the house, escorted there by a nun played by Imelda Staunton (Vera Drake), the movie settles down into a grueling pace as the main two characters get to know each other and Tomaz explores the incongruities of the decaying house.

Honestly, I’m already pretty burnt out on the religious horror movies between The Lodge and the still-unreleased Saint Maud, and the first inclination we get of any of the true horror to come is when Tomaz discovers some sort of mutated bat-like creature in the toilet, and things get even more disturbing from there. Although I won’t go into too many details about what happens, the movie suffers from some of the same issues as Relic where it’s often too dark to tell exactly what is happening. As it goes along, things just get weirder and weirder right up until a “what the fuck” moment that could have come from the mind of David Lynch.

I don’t want to completely disregard Garai’s fine work as a filmmaker since she’s made a mostly compelling and original horror movie – I have a feeling some might love this -- but the grueling pace and confusing narrative turns don’t really do justice to what might have been a chilling offering otherwise.

Going by the title and the fact it’s being released by Saban Films, I presumed that Ludwig and Paul Shammasian’s RETALIATION (Saban Films/Lionsgate) was gonna be a violent and gritty crime revenge thriller, but nothing could be further from the truth. Adapted by Geoff Thompson from his 2008 short film “Romans 12:20,” it stars Orlando Bloom as Malcolm, a troubled ex-con doing demolition work while fighting against his demons when he spots someone in the pub from his past that caused a severe childhood trauma.

This is another movie that I really didn’t know what to expect, even as it began and we followed Bloom’s character over the course of a day, clearly a very troubled man who has been dealing with many personal demons. Make no mistake that this is a tough movie, and it’s not necessarily a violent genre movie, as much as it deals with some heavy HEAVY emotions in a very raw way.

Honestly, I could see Geoff Thompson’s screenplay easily being performed on stage, but the way the Shammasian Brothers have allowed Malcolm’s story to slowly build as we learn more and more about his past makes the film so compelling, but they also let their actors really shine with some of the stunning monologues with which they’re blessed. While this is clearly a fantastic and possibly career-best performance by Bloom, there are also good performances by Janet Montgomery, as the woman who loves Malcolm but just can’t handle his mood changes. Also good is Charlie Creed-Miles, as the young priest who tries to help Malcolm.

I can easily see this film not being for everybody, because some of the things the film deals with, including pedophile priests and the effects their actions have on the poor, young souls who put their faith in them, they’re just not things people necessarily may want to deal with. Make no mistake that Retaliation is an intense character drama that has a few pacing issues but ultimately hits the viewer right in the gut.

A movie I had been looking forward to quite some time is the Marie Currie biopic, RADIOACTIVE (Amazon Prime), directed by Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis) and starring the wondrous Rosamund Pike as the famed scientist who helped discover radiation. Based on Lauren Redniss’ book, this is the type of Working Title biopic that would normally premiere in the Fall at the Toronto Film Festival, and sure enough, this one did. The fact it wasn’t released last year makes one think maybe this didn’t fare as well as potential awards fodder as the filmmakers hoped. It’s also the type of movie that works too hard to cater to the feminist resurgence from recent years, which ultimately ends up being its undoing.

The problem with telling Marie Currie’s story is that there’s so much to tell and Redniss’ book as adapted by Jack Thorne just tries to fit too much into every moment as years pass in mere minutes. There’s so much of Marie’s life that just isn’t very interesting, but trying to include all of it just takes away from the scenes that do anything significant. Maybe it’s no surprise that Thorne also wrote The Aeronauts, Amazon’s 2019 ballooning biopic that failed to soar despite having Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones as its leads.

I’m a similarly huge Rosamund Pike fan, so I was looking forward to her shining in this role, but she does very little to make Marie Currie someone you might want to follow, as she’s so headstrong and stubborn. This is the most apparent when she meets Pierre Currie, as played by Sam Riley, and maybe you don’t blame her for being cynical, having had much of her work either discredited or stolen by men in the past. Shockingly, Pike’s performance seems all over the place, sometimes quite moving but other times being overly emotive. Almost 90 minutes into the movie, Anya Taylor-Joy turns up as Curie’s grown daughter, and it’s one of the film’s biggest infraction, wasting such great talent in such a nothing role.

While Radioactive could have been a decent vehicle for Ms. Satrapi to flex her muscles as a filmmaker, the movie spends so much time having Currie fighting against the male-dominated science field that it loses sight of why she was such an important figure in the first place. Radioactive just comes across as a generally bland and unimaginative by-the-books biopic.

Also on Digital and On Demand this Friday is Chris Foggin’s FISHERMAN’S FRIENDS (Samuel Goldwyn Films), another quaint British comedy based on a true story, much like the recent Military Wives. Rather than being about a group of singing women, this one is about a group of singing men! What a twist!

Daniel Mays plays Danny, a music biz exec from London who travels to the seaside town of Port Isaac, Cornwall with some of his record company coworkers. Once there, they discover a local group of singing local fisherman, known as “Fisherman’s Friends,” who Danny wants to sign to a label. He also wants to get closer to Tuppence Middleton’s single mother Alwyn, who, no surprise, is also the only pleasant-looking younger woman in the town.

Fisherman’s Friends isn’t bad, but if you’ve seen a lot of British movies from the last few decades, then you’ve already seen this movie, particularly the “fish out of water” humor of a guy from the big city trying to relate to the down-to-earth ways of folk in a fishing village. It’s the type of really forced humor that is perfectly pleasant but not particularly groundbreaking in this day and age with so many filmmakers trying to do cutting-edge work.

Instead, this goes for a very typical and cutesie formula where everything works out with very little real conflict even when it throws in a needless subplot about the local pub falling on hard times and selling to a rich man who has little regard for the ways o the town. On top of that, and even if this wasn’t based on a true story, it’s very hard to believe anyone in the music industry or who buys records would be that interested in this group to make them worth signing a million-pound record deal. (Apparently, this really happened!)

I think it’s adorable that filmmakers are trying to turn character actor Daniel Mays (who you’ve seen in everything!) into a romantic lead, especially when you have James Purefoy right there! Instead, 56-year-old Purefoy is instead cast as Middleton’s father, while she’s put into a situation where she’s the love interest for a man that’s 23 years her elder. This kind of thing rarely bothers me as it does many younger female critics, but their romance is just ridiculous and unnecessary if not for the formula. As much as I enjoyed seeing Dave Johns from I, Daniel Blake as one of the singing fishermen, there really isn’t much for him to do in this.

If you like sea shanties and you are a woman over 60 (or have a mother that age) then Fisherman’s Friends is a cute butnever particularly hilarious British comedy that tries to be The Full Monty. But it never really tries to be anything more or less than the formula created by that movie 23 years ago, so it’s quickly forgotten after its saccharine finale.

Unfortunately, I just wasn’t able to get THE ROOM (Shudder/RLJE Films), the live action directing debut from Christin Volckman (Renaissance), but it’s now available on VOD, Digital HD, DVD AND Blu-Ray! It stars Olga Kurylenko and Kevin Janssens as a couple who leave the city to move into a an old house where they discover a secret hidden room that has the power to materialize anything they want, but this is a horror film, so what might seem like a fairy tale is likely to get dark. (I actually think I saw the trailer for this on Shudder, so I’ll probably check it out, and if it’s worth doing so, I’ll mention it in next week’s column.)

Yet another horror movie hitting On Demand this Friday is Pamela Moriarty’s A DEADLY LEGEND (Gravitas Ventures) that stars Corbin Bensen as a real estate developer who buys an old summer camp to build new homes unaware of the dark history of supernatural worship and human sacrifice. I’m gonna take the fifth on this one, which also stars Judd Hirsch and Lori Petty.

Available via Virtual Cinema through New York’s Film Forum and L.A.’s Laemmle is Gero von Boehm’s documentary, Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful (Kino Lorber), about the photographer who had a nearly five-decade career before dying in a car crash in 2006.

From Colombia to various Virtual Cinemas is Catalina Arroyave’s debut, Days of the Whale (Outsider Pictures) set in the city of Medellin, where it follows two young graffiti artists, Cristina and Simon, who tag places around where they live but coming from very different backgrounds, but they eventually bond while part of a revolutionary art collective.

Danny Pudi from Community and Emily C. Chang from The Vampire Diaries star in Sam Friedlander’s comedy Babysplitters (Gravitas Ventures) as one of two couples who have mixed emotions about having kids, so they decided to share one baby between them. Okay, then.

Netflix will also debut the rom-com sequel, The Kissing Booth 2, once again starring Joey King as Ellie, who is trying to juggle her long-distance romance with Jacob Erlodi’s Noah and her close friendship with Joel Courtney’s Lee. I haven’t seen the first movie. Probably won’t watch this one.

Next week, more movies in a variety of theatrical and non-theatrical release!

If you’ve read this week’s column and have bothered to read this far down, feel free to drop me some thoughts at Edward dot Douglas at Gmail dot Com, or tweet me on Twitter. I love hearing from my “readers,” whomever they may be.’

#Movies#Reviews#TheRental#Retaliation#Radioactive#YEsGodYes#VOD#Streaming#MostWanted#Amulet#TheWeekendWarrior

0 notes

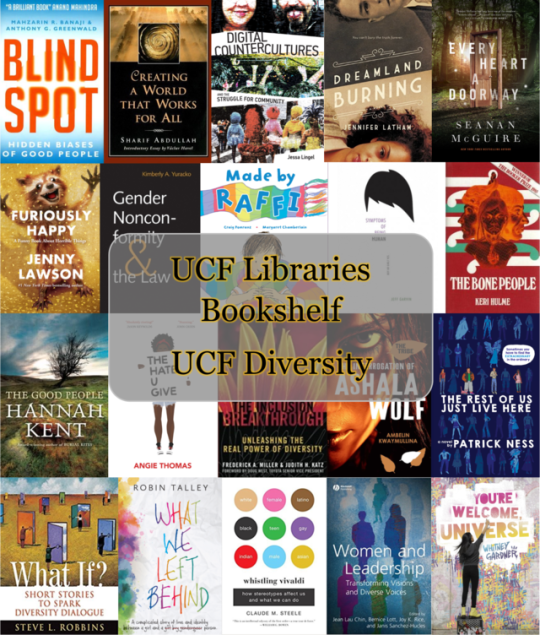

Photo

Every October UCF celebrates Diversity Week. This year’s dates are October 16 – 20, and the theme is Transform and Inspire Inclusion. University-wide departments and groups champion the breadth and culture within the UCF community, and work to increase acceptance and inclusion for everyone at UCF and the surrounding communities.

One of the fantastic things about UCF is the wide range of cultures and ethnicities of our students, staff, and faculty. We come from all over. We’re just as proud of where we are from as we are of where we are now.

For information about the Library Diversity Week activities visit: guides.ucf.edu/diversityweek

Join the UCF Libraries as we celebrate diverse voices and subjects with these suggestions (below the keep reading link)

And thank you to every Knight who works to help others feel accepted and included at UCF!

Blindspot: hidden biases of good people by Mahzarin R. Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald In this accessible and groundbreaking look at the science of prejudice, Banaji and Greenwald show that prejudice and unconscious biases toward others are a fundamental part of the human psyche. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Creating a World that Works for All by Sharif Abdullah (ebook) The world is a mess. The privileged few prosper. The masses suffer. And everyone feels spiritually empty. Most people would blame capitalism, racism, or some other "ism". But according to Sharif M. Abdullah, the problem is not ideology. It's exclusivity -- our desire to stay separate from other people. In Creating a World That Works for All, Abdullah takes a look at the mess we live in -- and presents a way out. To restore balance to the earth and build community, he says, people must stop blaming others, embrace inclusivity, and become "menders". He outlines three simple tests -- for "enoughness", exchangeability, and common benefit -- to guide people as they transform themselves and the world. Suggested by Schuyler Kirby, Rosen Library

Digital Countercultures and The Struggle for Community by Jessa Lingel Whether by accidental keystroke or deliberate tinkering, technology is often used in ways that are unintended and unimagined by its designers and inventors. Jessa Lingel tells stories from the margins of countercultural communities that have made the Internet meet their needs, subverting established norms of how digital technologies should be used. She examines a social media platform (developed long before Facebook) for body modification enthusiasts, with early web experiments in blogging, community, wikis, online dating, and podcasts; a network of communication technologies (both analog and digital) developed by a local community of punk rockers to manage information about underground shows; and the use of Facebook and Instagram for both promotional and community purposes by Brooklyn drag queens. By examining online life in terms of countercultural communities, Lingel argues that looking at outsider experiences helps us to imagine new uses and possibilities for the tools and platforms we use in everyday life. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Dreamland Burning by Jennifer Latham When Rowan Chase finds a skeleton on her family's property, she has no idea that investigating the brutal century-old murder will lead to a summer of painful discoveries about the past... and the present. Nearly one hundred years earlier, in 1821, a misguided violent encounter propels Will Tillman into a racial firestorm. In a country rife with violence against blacks and a hometown segregated by Jim Crow, Will must make hard choices on a painful journey towards self discovery and face his inner demons in order to do what's right the night Tulsa burns. Suggested by Christina Wray, Digital Learning & Engagement Librarian

Every Heart a Doorway by Seanan McGuire Children have always disappeared from Eleanor West's Home for Wayward Children under the right conditions; slipping through the shadows under a bed or at the back of a wardrobe, tumbling down rabbit holes and into old wells, and emerging somewhere ... else. But magical lands have little need for used-up miracle children. Nancy tumbled once, but now she's back. The things she's experienced ... they change a person. The children under Miss West's care understand all too well. And each of them is seeking a way back to their own fantasy world. But Nancy's arrival marks a change at the Home. There's a darkness just around each corner, and when tragedy strikes, it's up to Nancy and her new-found schoolmates to get to the heart of the matter. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Furiously Happy: a funny book about horrible things by Jenny Lawson Jenny Lawson is beloved around the world for her inimitable humor and honesty, and in Furiously Happy, she is at her snort-inducing funniest. This is a book about embracing everything that makes us who we are - the beautiful and the flawed - and then using it to find joy in fantastic and outrageous ways. Because as Jenny's mom says, "Maybe 'crazy' isn't so bad after all." Sometimes crazy is just right. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Gender Nonconformity and the Law by Kimberly A. Yuracko When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, its primary target was the outright exclusion of women from particular jobs. Over time, the Act's scope of protection has expanded to prevent not only discrimination based on sex but also discrimination based on expression of gender identity. Kimberly Yuracko uses specific court decisions to identify the varied principles that underlie this expansion. Filling a significant gap in law literature, this timely book clarifies an issue of increasing concern to scholars interested in gender issues and the law. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Made by Raffi by Craig Pomranz; illustrated by Margaret Chamberlain As a shy boy, Raffi is a loner and teased at school until one day he discovers knitting and decides to make a scarf for his father and a cape for the prince in the school play. Suggested by Cindy Dancel, Research & Information Services

Symptoms of Being Human by Jeff Garvin A gender-fluid teenager who struggles with identity creates a blog on the topic that goes viral, and faces ridicule at the hands of fellow students. Suggested by Cindy Dancel, Research & Information Services

The Good People by Hannah Kent (on order) Based on true events in nineteenth century Ireland, Hannah Kent's startling new novel tells the story of three women, drawn together to rescue child from a superstitious community. Nora, bereft after the death of her husband, finds herself alone and caring for her grandson Micheál, who can neither speak nor walk. A handmaid, Mary, arrives to help Nóra just as rumours begin to spread that Micheál is a changeling child who is bringing bad luck to the valley. Determined to banish evil, Nora and Mary enlist the help of Nance, an elderly wanderer who understands the magic of the old ways. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

The Bone People: a novel by Keri Hulme Kerewin, a part-Maori painter living in self-exile, is drawn out of her isolation by a mute boy who is cast up on a beach, the only survivor of a shipwreck. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas Sixteen-year-old Starr Carter moves between two worlds: the poor neighborhood where she lives and the fancy suburban prep school she attends. The uneasy balance between these worlds is shattered when Starr witnesses the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend Khalil at the hands of a police officer. Khalil was unarmed. Soon afterward, his death is a national headline. Some are calling him a thug, maybe even a drug dealer and a gangbanger. Protesters are taking to the streets in Khalil's name. Some cops and the local drug lord try to intimidate Starr and her family. What everyone wants to know is: what really went down that night? And the only person alive who can answer that is Starr. But what Starr does or does not say could upend her community. It could also endanger her life. Suggested by Andrew Hackler, Circulation

The Inclusion Breakthrough: unleashing the real power of diversity by Frederick A. Miller & Judith H. Katz The Inclusion Breakthrough cuts a path through this potential minefield, offering a proven methodology for strategic organizational change, including models for diagnosing, planning, and implementing inclusion-focused, culture-change strategies tailored to each organization's individual needs. It also describes the key competencies for leading and sustaining a culture of inclusion. Offering real-world results of ''before and after'' surveys, including anecdotal and statistical reports of organizational change achieved using the methodologies described, Suggested by Sandy Avila, Subject Librarian

The Interrogation of Ashala Wolf by Ambelin Kwaymullina Taking refuge among other teens who are in hiding from a government threatened by their supernatural powers, Ashala covertly practices her abilities only to be captured and interrogated for information about the location of her friends. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

The Rest of Us Just Live Here by Patrick Ness What if you aren't the Chosen One? The one who's supposed to fight the zombies, or the soul-eating ghosts, or whatever the heck this new thing is, with the blue lights and the death? What if you're like Mikey? Who just wants to graduate and go to prom and maybe finally work up the courage to ask Henna out before someone goes and blows up the high school. Again. Because sometimes there are problems bigger than this week's end of the world, and sometimes you just have to find the extraordinary in your ordinary life. Even if your best friend is worshiped by mountain lions. Suggested by Christina Wray, Digital Learning & Engagement Librarian

What if?: short stories to spark diversity dialogue by Steve L. Robbins Hiring and retaining the best and brightest talent is what defines market leadership today. And in the global marketplace winning the war for talent means embracing differences, discovering other worldviews, and reframing our organizations for competitive advantage. What If? delivers a creative and innovative way to explore the issues that dominate today's multicultural workplace: leadership and mentoring, creativity and innovation, organizational culture and engagement. In 25 inspiring stories-some deeply personal-Steve Robbins offers fresh insight into the real and meaningful differences among people and how the power of everyday experiences can be the catalyst for seeing the world through a different lens. What If? also presents specific ideas of what organizations can do toengage our global world, build core competencies in diversity and inclusion, and benefit from the best talent available - regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, race, or disability. Suggested by Sandy Avila, Subject Librarian

What We Left Behind by Robin Talley From the critically acclaimed author of Lies We Tell Ourselves comes an emotional, empowering story of what happens when love may not be enough to conquer all. Toni and Gretchen are the couple everyone envied in high school. They've been together forever. They never fight. They’re deeply, hopelessly in love. When they separate for their first year at college—Toni to Harvard and Gretchen to NYU—they’re sure they’ll be fine. Where other long-distance relationships have fallen apart, theirs is bound to stay rock-solid. The reality of being apart, though, is very different than they expected. Toni, who identifies as genderqueer, meets a group of transgender upperclassmen and immediately finds a sense of belonging that has always been missing, but Gretchen struggles to remember who she is outside their relationship. Suggested by Cindy Dancel, Research & Information Services

Whistling Vivaldi: and other clues to how stereotypes affect us by Claude M. Steele In this work, the author, a social psychologist, addresses one of the most perplexing social issues of our time: the trend of minority underperformance in higher education. With strong evidence showing that the problem involves more than weaker skills, he explores other explanations. Here he presents an insider's look at his research and details his groundbreaking findings on stereotypes and identity, findings that will deeply alter the way we think about ourselves, our abilities, and our relationships with each other. What he discovers is that this experience of "stereotype threat" can profoundly affect our functioning: undermining our performance, causing emotional and physiological reactions, and affecting our career and relationship choices. But because these threats, though little recognized, are near-daily and life-shaping for all of us, the shared experience of them can help bring Americans closer together. In a time of renewed discourse about race and class, this work offers insight into how we form our sense of self, and lays out a plan that will both reduce the negative effects of "stereotype threat" and begin reshaping American identities Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Women and Leadership: transforming visions and diverse voices edited by Jean Lau Chin Over the past thirty years the number of women assuming leadership roles has grown dramatically. This original and important book identifies the challenges faced by women in positions of leadership, and discusses the intersection between theories of leadership and feminism. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

You're Welcome, Universe by Whitney Gardner When Julia finds a slur about her best friend scrawled across the back of the Kingston School for the Deaf, she covers it up with a beautiful (albeit illegal) graffiti mural. Her supposed best friend snitches, the principal expels her, and her two mothers set Julia up with a one-way ticket to a "mainstream" school in the suburbs, where she's treated like an outcast as the only deaf student. The last thing she has left is her art, and not even Banksy himself could convince her to give that up. Out in the 'burbs, Julia paints anywhere she can, eager to claim some turf of her own. But Julia soon learns that she might not be the only vandal in town. Someone is adding to her tags, making them better, showing offand showing Julia up in the process. She expected her art might get painted over by cops. But she never imagined getting dragged into a full-blown graffiti war. Suggested by Emma Gisclair, Curriculum Materials Center

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcast: The Trauma of Racism- An Open Dialogue

As the world watched in horror the brutal murder of George Floyd by a police officer, many people are searching for answers. In today’s Psych Central Podcast, Gabe and Okpara Rice, MSW, tackle all of the tough subjects: white privilege, systemic racism, disparities in education and the concept behind Black Lives Matter.

Why does racism still exist in America and what can be done? Tune in for an informative discussion on race that leaves no stone unturned. This podcast was originally a live recording on Facebook.

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘Okpara Rice- Racism Trauma’ Podcast Episode

Okpara Rice joined Tanager Place of Cedar Rapids, Iowa in July 2013, and assumed the role of Chief Executive Officer in July 2015. Okpara is the first African American to hold executive office at Tanager Place in its more than 140-year history. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Social Work from Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois, and a Master of Social Work from Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. Okpara lives in Marion, Iowa with his wife Julie and sons Malcolm and Dylan.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘Okpara Rice- Racism Trauma‘ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast, we are recording live on Facebook. And for this special recording, we have Okpara Rice with us. Okpara Rice joined Tanager Place of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in July of 2013 and assumed the role of chief executive officer in July of 2015. Now, Okpara is the first African-American to hold executive office at Tanager Place in its more than 140 year history. He also holds a Bachelor of Science in Social Work from Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois, and he has a Master’s of Social Work from Washington University from St. Louis, Missouri. Okpara lives in Marion, Iowa, with his wife, Julie, and sons Malcolm and Dylan. Okpara, welcome to the podcast.

Okpara Rice: It’s good to be with you again, Gabe. It was good to see you, man.

Gabe Howard: I am super excited for you to be here. There’s a lot going on in our country right now that necessitated conversations that, frankly, should have happened centuries ago. And you brought to my attention that there’s a lot of trauma involved in racism. Now, that’s something that I had never really considered. I want to state unequivocally, I think that racism is wrong and that it’s bad. And a month ago at this time, I would have thought that I understood what was going on. And I’m starting to realize that I may understand a skosh, but I don’t understand a lot. And you suggested an open dialog to talk about racism, race relations and the trauma that you’ve been through. And I want to say I appreciate you being willing to do so because it’s a tough conversation.

Okpara Rice: I appreciate you, man, being open to it and just I’ve always appreciated your friendship and being a colleague and knowing that what we have to do for our society is to have conversations with each other, to be vulnerable and not be afraid to ask questions of each other. If we don’t do that, we’re not going to learn. We’re not going to gain enough of a perspective and it’s definitely not going to help us move the community forward. So I just appreciate you having me today and look forward to the dialog.

Gabe Howard: Thank you so much for being here. All right. Well, let’s get started. Okpara, why do you think that racism is still an issue?

Okpara Rice: Man, that’s a way to jump right in there, Gabe, I’ve got to tell you. Because we’ve never really dealt with it as a country. As we’ve evolved as a country, we try to think we continue to make advancements, but there are some fundamental things that we have not really addressed. We know Bryan Stevenson down south, who runs the Equal Justice Initiative, was speaking about this a couple of years ago around how we have never come to reconciliation, even around slavery, around lynching. There are things that are just really uncomfortable for us as a society to talk about. And what we know is that there has been systems built. You go back to the beginning of slavery, you go further than that around making sure people are disenfranchised. And so we have these very concrete systems that are entrenched in the very fabric of our society to make sure that some segments, African-Americans sometimes in particular. And I’m an African-American. But there are other segments from all socio-economic levels that people don’t get ahead. And they’re designed that way. It is very hard to go back and look at how we are built as a country, right from the roots of slavery and someone else’s labor to build wealth and then to go back and think about where we are today.

Okpara Rice: Until we really address those core issues of who we are and how we evolved as a country and reconcile some of that painful history. I don’t know if we’re gonna get there. I will tell you, though, I am hopeful. I have never, I’m 46 years old, seen as much conversation as I have right now. And you think about all the horrific incidents that have happened. There’s something that really just resonated all of a sudden. And I mean, think about it, I got an email the other day from PetSmart, telling me Black Lives Matter. What is going on? Right. And so, what changed is we watched another black man die, and it just was the tipping point. And I think that these conversations are critical and it’s going to bring about some reform. I hope to bring about some reform. And let’s not forget we’re in the middle of a pandemic. And so people feel as strongly as possible right now and are out there marching and protesting in the middle of a pandemic. So I should tell you that this is a conversation whose time has come and well overdue.

Gabe Howard: Will Smith said that racism hasn’t changed and police misconduct hasn’t changed and treatment of African-Americans hasn’t changed. We’re just starting to record it because of cell phone cameras. And he feels, I’m not trying to take his platform, but he feels very strongly that this has been going on since pretty much the beginning of America. And we’re just now able to get it televised in a way that people can respond to. I grew up learning about Dr. King. He wrote the book Tales from a Birmingham Jail when he was in jail in Alabama, and we’re like, look, look what he did. Look at this amazing thing. He made lemonade out of lemons. But how do you feel about the headline not being a law abiding African-American man put in jail for doing nothing wrong? And we’re still talking about police reform. And this literally happened in the 60s.

Okpara Rice: We have been talking about. I had the pleasure of meeting Adam Foss a few years ago, and Adam is a former prosecutor out of Boston who has been talking about prosecutorial reform for years. And the criminal justice, the new Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander’s book, these things are out there. What happens is that we just have not been paying attention. Nothing has changed. The data has been there. What we know around the disproportionality and criminal justice system, disproportionality and how education is funded and housing and access to. Well. That does not change. That data has been there. The reality is that we have not paid attention to it for some reason, collectively as a society. And so when we look at that and we talk about the news and how black men are portrayed or even people who are protesting, none of it really surprises me. Because it’s not. That’s not a fun story to say, you know, protester who was doing nothing arrested. It doesn’t really matter. When we’re saying we have someone who may have done a minor crime, who was basically murdered in cold blood with a video camera pointed directly at them. And still, that didn’t make the police officer move or feel like he had anything he needed to correct.

Okpara Rice: That says a lot about who we are as a society. And I think that is a real breaking point. And remember, we just had also, Breonna Taylor, that situation happened down in Kentucky and then Ahmaud Arbery that just happened where two men decided to do a citizen’s arrest for a guy that is jogging. So it just says that we have got to open dialogue and look at addressing these things head on and calling a spade a spade. And that is hard for people to do. And if we think that the media, whoever it is going to, you know, their job is to sell papers, to get viewership. And so those things are the most inflammatory, is always what’s going to hit there, right? So you look at just recently even this, all the news coverage around the rioters and the looters. You’d think just absolute chaos. But it didn’t really talk about the thousands and thousands and thousands of people who were out there just marching and protesting peacefully of all creeds and colors. It just says like you go to the lowest common denominator because that’s what seems to grab people’s attention. But that doesn’t make it right. And some of those stories have not been told.

Gabe Howard: It struck me as odd that there is this belief that everybody is always acting in concert. As a mental health advocate, I can’t get all mental health advocates to act in concert with one another. There’s lots of infighting and disagreement in the mental health community. Now, you are a CEO of an organization. And I imagine that you and your employees are not always in lockstep. There’s disagreements, there’s closed door meetings, and you obviously have a human resources department. Everybody understands this. But yet, in the collective consciousness of America, people are like, OK, all the protesters got together. They had a meeting at Denny’s and here’s what they all decided to do. And this sort of becomes the narrative and that the protesters are looting. Well, isn’t it the looters who are looting? It’s a little bit disingenuous, right? And that really leads me to my next question about the media. Do you feel that the media speaks about African-Americans in a fair way, a positive or negative way? As a white male, the only time I ever feel that the media is unfair to me is when they talk about mental illness. The rest of the time, I feel that they’re representing me in a glowing, positive light. How do you feel about the media’s role in all of this?

Okpara Rice: As an African-American male, first of all, people see us as this threat no matter what. That’s just sort of a given. We have seen that it was actually not that long ago, I forgot who did the study was when you look at two of the same infractions that if there was a white person doing the same infraction, they put up a picture of them in their prep school or a high school picture, looking all young and fresh, and it was an African-American person who got arrested for something. What they portray them is like the worst possible picture you can find to make them look the part. And I think they actually did this with Michael Brown down in Ferguson, after he got killed. It plays into the narrative that we are scary. We’re big. We’re loud. And people should be afraid of us. This sort of gets perpetuated, has got perpetuated in movies, gets perpetuated on film. And things have gotten better because people are standing up and saying there’s a lot of black excellence in this country. Not everybody is a criminal. Millions of hard working and wonderful African-American professionals out there who are just taking care of their families, being great fathers, being great moms. Those are the stories that need to be out there. Those stories are not as sexy, though. That’s not as sexy as saying, oh, my God, we’re looking at some guy running down the street after he grabbed a TV from Target. Whether than saying, oh, my God, there were whole communities that came out together, put masks on and are marching for civil justice. A march for social justice. That’s a different type of story. So I do feel like some journalists are on the ground trying to do a better job of telling that story, because we have to demand that story is told. But we also know that the media is under target. Right. Newspapers are dying across the country. We know that the larger scale media is owned by large corporations. And so,

Gabe Howard: Right.

Okpara Rice: Again, it goes back to the different metrics that are being used. You know, I hope the local media continues to be able to tell those stories in those communities, because that is really important, that people do see others who are being positive to break that sort of stereotype that we’re all waiting to break into somebody’s house, it’s Birth of a Nation type stuff, man.

Gabe Howard: To give a little context, I maintain excellent relationships with police through the C.I.T. program. Now, C.I.T. is the mental health program for crisis intervention. And I’ve asked a lot of police officers how they feel about this. And one person said, look, people hate us now, but I’m not surprised because we were raised on this idea that if you see something wrong, it’s representative of the entire group. We’ve stoked that fire and we’ve raised it. And we’ve been okay with it. We’ve been okay with, oh, we see something in the black community that we don’t like. It’s representative of the entire community. And then we just moved on with our day. Well, now, all the sudden, people are starting to see something that they don’t like in policing or law enforcement. And we’ve decided, oh, that must be everybody. And, well, that’s what we are trained to believe. I can’t imagine, and I’m not trying to put words in your mouth, Okpara. I can’t imagine that you believe that every single police officer is bad. I’ve worked with you on C.I.T. before. So I know that you don’t feel that way. But how do you handle that?

Okpara Rice: I want to reframe it for you just a little bit.

Gabe Howard: Please.

Okpara Rice: And people say, well, why are African-Americans so frustrated about the police? Because we’ve been telling you these things that have been happening for decades. All right? When you have been saying the same thing over and over again and then people realize, oh, wait a minute, this actually is a thing. It’s kind of infuriating, right? Of course, not every police officer is horrible. I have a good relationship with the police chief here. Of course not. But we cannot deny that there is a fundamental systems problem that has to be addressed in policing and criminal justice. It just cannot be denied. The data is there. Again, that’s how people like to divide us. It gets us on this whole, you must hate them, they’re not good. It’s not about that. It’s about the system, the system that has been holding people down. And you have disproportionality in the criminal justice system for the same felonies, misdemeanors, whatever, that a white counterpart will have, African-Americans drastically, statistically, are way out of proportion with the population. So, I mean, those are things that cannot be denied. And this has been going on for decade after decade after decade.

Okpara Rice: You know, I talked to some officers and again, they’re good people at this tough job. I’ve never been a police officer. I have no idea what that experience is like. But it is very hard. When you look on TV, you know, once again, we go back to the media. When you see people, police officers, when you’re protesting for brutality and then you see police officers beating up on people protesting for brutality. Even in the last week, there have been officers across the country arrested for assault and all kinds of other things. Right. So that’s just happened. But these things are real. And so it’s not that people hate police. People hate a system that disenfranchises whole segments of society. That’s the issue. And that’s what has to be addressed. That’s why reforms can’t happen if a community and a city and everybody is a part of it, don’t come to the table and say we collectively believe this is wrong. And that’s how you have change.

Gabe Howard: One of the things that keeps being said is that, you know, it’s just a few bad apples, it’s just a few bad apples, it’s just a few bad apples. But, you know, for example, in the case of the few bad apples that pushed a 75 year old man and cracked his skull open, the 57 people quit. To, I don’t know, show solidarity that they should be allowed to shove elderly people for, I don’t know, back talking, I guess? So we have the bad actors. We have the bad apples. We’ll leave that sit there that they did the pushing. But why did the other officers feel the need to stand up and say, no, we want to protect our right to push? That takes away from this idea that it’s only a few bad apples, that if everybody is propping up those apples and, you know, not for nothing, nobody ever finishes that quote. It’s a few bad apples spoil the barrel. And if you’re not removing those apples? Do you feel that part of the problem is that nobody is holding the bad actors accountable and that the police sort of close ranks to protect the people that are maybe doing things that are, well, dangerous?

Okpara Rice: Gabe, I would say, again, I’m not a police expert. This is my one perspective is growing up in my skin and my experience. Every organization, every industry, every business has a culture to it. So those who are policemen know what the police culture is like. Know what is expected of each other. Know what the blue wall is. We’ve had that conversation. There are books and articles written about that. I don’t know if people want to cover for that if that is saying, hey, we believe it’s okay to shove a 75 year old guy down. I’m sure most of them wouldn’t want that. If you think about would they want that for their mom or their own dad. But the conversation, again, we lose sight of the conversation. It’s about what do they think is okay use of force? The policy in front of us, talking about what is an OK use of force and having some agreement about when you become aggressive. What that is supposed to look like. So that there is a social agreement with everyone saying this is what’s OK. When I saw the video of the guy getting knocked down and everybody sort of looked at him and then sort of kept it moving. I was like, God, that’s just cold. Right. Yeah.

Gabe Howard: Yeah.

Okpara Rice: But I wasn’t there. I don’t know the dynamics. And from the outside, that’s just crazy to me. But those people who decided to step off of that, they have to attune for themselves and their own morality and ethics. But that’s a conversation among law enforcement that they have to have because they have their own culture. I’m not of their culture, so I can’t speak to what it is like to be an officer, but it’d be fascinating to know and be a fly on the wall of a room behind closed doors. I’d be shocked to see anybody say, gosh, that was good. No, because most officers you talked to off the record say that’s nonsense and we can’t do this. We know we need to get better. So then they have that collective voice and that I don’t know.

Gabe Howard: We’ll be right back after these messages.

Sponsor Message: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com. Secure, convenient, and affordable online counseling. Our counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face to face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counseling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Gabe Howard: We’re heading back to our live recording of The Psych Central Podcast with guest Okpara Rice discussing the trauma of racism. Based on what I’ve seen in the past few years and especially what I’ve seen in the last 10 days, it’s difficult not to just have this knee jerk reaction of why is this okay? Why have we tolerated this? And when you started to look at the research and the facts and figures and then when I started talking to my African-American friends, I realized I am not afraid of the police. I could not find one nonwhite person who said that they weren’t afraid of the police. And I don’t know what the solution is. I’m not even sure I understand the problem. But that’s very striking to me that every single nonwhite person that I met was like, look, Gabe. Between me and you, no, I’m terrified of them. And that’s got to suck if you’re law enforcement. But listen, that’s really got to suck if you’re not white. What are your thoughts on that?