#cos of the number of thirst edits using that scene

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

nah people using that ballerina scene of kim jihoon literally getting ready to rape a girl in their thirst edits is crazy

#i get that ppl love the actor yall think hes hot sure make edits of him thats fine#but using that scene is psychotic yall rly missed the entire point of the movie#searched up ballerina on here and tiktok to see the cool revenge edits and now i genuinely feel physically sick#cos of the number of thirst edits using that scene#yall are disgusting#ballerina#ballerina kmovie#ballerina 2023#kim ji hoon#mine#kmovie

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you do a one shot of MK1 Johnny with a street racer reader?

Johhny Cage x Street Racer Reader

Johnny was in peak of his career, every movie he was in earning award after award. He was practically expected in every action movie of the decade, along with the occasional rom com. So here he is, looking over the long list of films his agent had procured for him to star in. Most had been by the request of their directors, but a few were movies his agent went out of his way to look into.

Being that films took years of work to film and edit, reshoots and last second voice overs, Johnny could only really commit to one, and the occasional small series or backup role. Looking through the list his attention was caught by a high pace action movie where he would star as the lead; an undercover cop trying to crack down on Los Angeles' street racing epidemic, only to be drawn into numerous hijinks.

It seemed like an interesting concept, the script was good, and he did have experience with this studio and director. But the real draw was the warning that was attached with the script.

Due to the risk factor involved in numerous stunts, scenes, as well as for realisms purposes. All cast members will be required to take safety courses as well as in constant supervision of professional consultant at all times.

He was going to be doing his own stunts and working with a real street racer. If that didn't have 'Cage Flick' written all over it in bold he didn't know what did.

He of course got the part, he still questioned why the audition was even necessary.

His first day on set was simple enough, meeting the cast and crew, as well as a few brief investors for the movie. That was until he met you.

You had grown up in LA and gotten into street racing fairly young, so naturally you were the best pick for this job. And the producers were willing to pay a fuck ton to be able to advertise that extra layer of 'authenticity'.

You were an instant hit with the cast, getting along with nearly all of them instantly. Johnny in particular was rather captivated. It was your first time meeting such a high-profile celebrity, even as a born and raised LA resident.

The attraction on Johnny's part was immediate. Confident, hot, and looked damn good in the driver seat.

Throughout shooting, you had coached Johnny on safety guidelines and how to do complex drifts and turns.

That wasn't to say the attraction was one-sided. Hell, you had thirsted over this man with your friends when you binged his movies. So, when you heard the director making fun over him about his less than hidden attraction towards you, you took your chances.

A hand guiding his when instructing him how to use the gear shift, giving him pats on the back when he figured out how to pull off the reversed driving sequence, and being extra sure he was behind you when you decided to bend over to inspect the hood of the car. (there was nothing wrong with it)

Despite what media would have you think, being an actor is a very busy and grueling job. Johnny had wanted to ask you out a number of times, but by the point he had enough courage and confidence that you were also interested, filming had wrapped up.

So here he was, sitting in an Italian tux, surrounded by some of the most talented minds in the filming industry, with an Oscar nomination, wondering where the hell it all went wrong.

"Johnny" he looked to his co-star sitting to his left. Looking down to see the small bound together papers with the word 'draft' on it.

"It's soon, but, by the looks of it.... It's been greenlit" A sequel?

Well, seeing as he was the main lead, it was no doubt they'd need him to come back. And if they did?

He knew the condition he was going to demand if they wanted him.

Maybe he could finally ask you out for that drink.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starring Role!Patrick

i made a new post because there was no place to fit this on the chain

I'm bored so Imma ramble off ideas for the three series of Star!Patrick ^w^

Series one

Said here, this season is spent on the friendship between Miccah, Patrick's character and [Rowan?], a co-star of the show; Hell's Secrets. I like to think of Miccah and [Rowan's] relationship as "opposites attract". Like, tons of banter between the two of them, as well as sarcasm and coldness from Miccah's side and pure sunshine and kindness or something from [Rowan]. Ooh! And the difference in how they react when they're called to help investigate a murder. Like, Miccah is calm and uncaring to the sight of a mutilated body, whereas Rowan is on edge and on the verge of passing out every second they're in the same vicinity as the body. Then, the first season ends and leaves viewers wanting more (because Patrick is hot) when Miccah shoots a character between the eyes with no remorse. Was this death foreshadowed? Was it sudden? Whatever it is, it shocks a bunch of viewers, especially Patrick's family, as they thought the show was more of a "whodunnit?" type show.

Series two

Said here, season two is his descent into murder. And because of the number of crimes Miccah has seen go wrong and the murderer be caught for dumb mistakes, such as putting the body in the boot of their car, killing someone with a weapon (usually a knife or gun) they own, never using cash, or even leaving cold hard evidence. It'd only be natural for Miccah to be able to commit perfect murders, never getting caught and satiating his bloodlust. I love the idea of Miccah still being friendly with [Rowan]; despite showing every single one of his victims pure coldness and hostility, going as far as to torture them before letting them die because he loves it when people cry and plead for him to shoot them between the eyes. And! Miccah being adrenalised with the thrill of a kill a bit ago, breathing heavily and being giggly and seeing [Rowan] cry or be upset by a body and Miccah side-eyeing them and having to fight his bloodlust so he doesn't hurt/kill them (see point three). This is also the season where Patrick gets revealed.

Series three

In the last season, in which Miccah is tracked down by the police, the ending is ambiguous to viewers. There'd probably be tons of theories regarding season three, which Patrick would love to reading and comment on. Patrick would have a few of his own, too, because I doubt he actually knows what happens at the end of season three. There's not really much I can say about this season, haha...

Series four (just an idea!!)

This season could happen, maybe it's just a few episodes long, or maybe it's the longest season. My idea for this season is that it plays on the theories made about season three, that Miccah makes an escape, and will eventually die. When he's on the run, I like the idea of it playing on his character's coldness and uncaringness for others by having him rob people, kill people so he can steal their car, e.t.c. The end of the season is a really tense meeting between Miccah and [Rowan], which would eventually end in Miccah killing [Rowan] and then himself. And the credits would roll as the police cars roll up and burst into the room, and it ends with "The devil is dead."

Jus' Liddol Tidbits !

彡✧.*☆ Patrick "cosplaying" (is it considered cosplay if you are the character?) as Miccah on TikTok or something and duetting videos of people cosplaying as [Rowan]!

彡✧.*☆ Oh! Or, maybe, Patrick "cosplaying" as Miccah, and Ciero as [Rowan]?

彡✧.*☆ Patrick, as he's watching it, just spouting off trivia and telling them about his favourite scenes!

彡✧.*☆ (Based sorta off of Pretty Boy Patrick™) He would have so many simps after finishing filming on "Hell's Secrets". Like, he would have so many edits and thirst traps of him, and he'd be like 😳. For things like meet-and-greets, he'd have such a long line; and he'd make sure to take his time with all his fans!

彡✧.*☆ I see Miccah as having tons of rings/jewellery for some reason?? I'm talking about earrings/piercings, rings, necklaces, bracelets, e.t.c. And he also definitely smokes after killing; you can't convince me otherwise.

✩‧.ೃ࿐˚ I don't have anything else to add, haha! if you wanna add anything, Mod, please do! fuel my need for SR!Patrick

#i love patrick#idk why he has me in a chokehold#and im not mad#eldritch-hall-asylum#starring role patrick#starring role patrick au#tw murder#tw murder mention#tw violence mention#tw violence

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Personality Crisis: The Radical Fluidity of Todd Haynes’ ‘Velvet Goldmine’ by Judy Berman

[This month, Musings pays homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to film we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutter’s Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Over the next four weeks, Musings will offer its own selection of tarnished gems, in the hope they’ll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. —Scott Tobias, editor.]

Like the glam rockers it gazes upon through the smoke-clouded lens of memory, Velvet Goldmine is most beautiful when it descends into chaos.

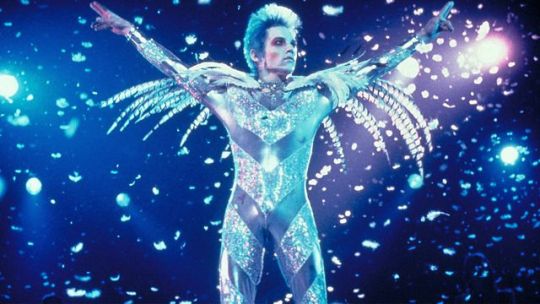

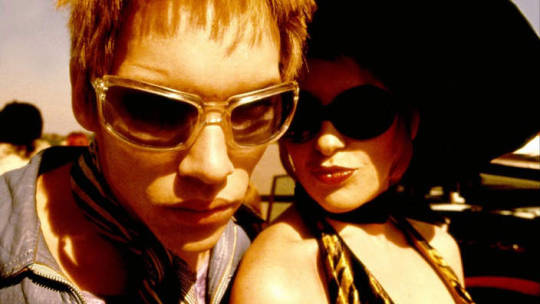

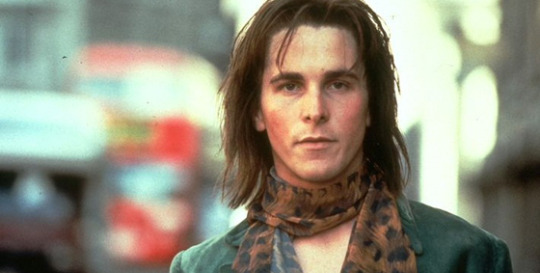

Stolen, the way great artists do, from Citizen Kane, the skeleton of Todd Haynes’ 1998 film is a chain of interlocking reminiscences of Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a David Bowie-like glam rocker who fakes his own onstage death in the mid-’70s. A decade later—in that most dystopic of years, 1984—his ex-wife Mandy (Toni Collette) and former manager Cecil (Michael Feast) relate their bitter tales of betrayal to a journalist (Christian Bale) whose assignment has him reluctantly reliving his own teenage sexual awakening under the influence of Brian’s music. Between the interviews, musical numbers, and onscreen epigrams, there’s also a mysterious female narrator who sometimes surfaces, like a teacher reading a subversive storybook, with dreamy exposition that reaches back a century to invoke glam’s patron saint, Oscar Wilde.

The film climaxes with a propulsive sequence of scenes that are exhilarating precisely because they merge all of these points of view, subjective and omniscient, into one collective fantasy. Brian and his new conquest, the Iggy Pop/Lou Reed composite Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), ride mini spaceships at a carnival to Reed’s “Satellite of Love.” Two random schoolgirls, their faces obscured, act out a love scene between a Curt doll and a Brian doll. In a posh hotel lobby, Brian’s entourage, styled like Old Hollywood starlets on the Weimar Germany set of a fin-de-siècle period film, recites pilfered sound bites about art. Then Brian and Curt are kissing on a circus stage, surrounded by old men in suits. They play Brian Eno’s “Baby’s on Fire” as Haynes cuts between the performance, an orgy in their hotel suite, and Bale’s hapless, young Arthur Stuart masturbating over a newspaper photo of Brian fellating Curt’s guitar. Stripped of narration—not to mention narrative—the film seems to be running on its own amorous fumes, its story fragmenting into a heap of glittering images as it hurtles from set piece to set piece.

Visual pleasure aside, it’s a perfect way of translating into cinematic language the argument that underlies Haynes’ script—that glam’s revelations about the radical fluidity of human identity go far beyond sex and gender. As the apotheosis of teen pop audiences’ thirst for outsize personae, fictional characters like Ziggy Stardust (who Velvet Goldmine further fictionalizes as Slade’s alter ego, Maxwell Demon) melded the symbiotic identities of artist and fan into a single, tantalizing vision of hedonism and transgression. Kids imitated idols they didn’t quite recognize as pure manifestations of their own inchoate desires. Musician and fan became each other’s mirror, and both could become entirely new people simply by changing costumes or names.

But it’s pretty much impossible to imagine Velvet Goldmine’s distributor and co-producer, Harvey Weinstein, appreciating this as he watched the film for the first time—or seeing anything in it, really, besides an expensive mess.

Haynes and his loyal producing partner, Killer Films head Christine Vachon, had already been through hell with Velvet Goldmine by the time they delivered a cut to Miramax. Bowie had refused Haynes’ repeated requests for permission to use six Ziggy-era songs in the film, claiming that he had a glam movie of his own in the works. And in a production diary that appears in her book Shooting to Kill, Vachon points out one unique challenge of making a film about queer male sexuality: “The MPAA seems to have a number of double standards. Naked females get R ratings, but pickle shots tend to get NC-17s. Our Miramax contract obligates us to an R.” She also mentions that an investor pulled $1 million of funding just weeks before filming.

The shoot was even more harrowing than the two veteran indie filmmakers could’ve predicted. As they fell behind schedule, a production executive started nagging Vachon to make cuts. “Todd is miserable,” she wrote in her diary the night before they wrapped. “He says that making movies this way is awful and he doesn’t want to do it.” In an interview that accompanies the published screenplay for Velvet Goldmine, Oren Moverman asks Haynes, “Was the making of the film joyful for you?” “I’m afraid not,” he replies. “We were trying very hard to cut scenes while shooting, knowing that we were behind and we didn’t have the money for the overloaded schedule. But there was hardly a scene we could cut without losing essential narrative information.” It’s remarkable that he managed to capture 123 usable minutes’ worth of meticulously art-directed ‘70s excess (and ‘80s bleakness) in just nine weeks, under so much external pressure, on a budget of $7 million.

When the film finally reached Harvey Scissorhands, after months of editing, Weinstein told Haynes it was too long and the structure didn’t work. “He made suggestions that I didn’t follow, and then he just buried it,” the director told Down and Dirty Pictures author Peter Biskind. What happened next comes straight from the Weinstein playbook: “Even afterward,” Haynes remembered, “they threw out a DVD, they didn’t ask for a director commentary, my name wasn’t on the cover of it, it was buried in the minuscule billing block. He can’t even do the really small things that don’t cost anything—he never shows any respect.” (That Haynes never found a distributor he preferred to Weinstein, with whom he reunited for I’m Not There and Carol, speaks volumes about the way Hollywood treats ambitious filmmakers.)

After it failed to blow audiences away at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, Miramax effectively dumped Velvet Goldmine. It debuted on just 85 screens that November, ultimately grossing about $1 million stateside. Its ridiculous theatrical trailer might well be a glimpse at the movie Weinstein was expecting: a “magical trip back to the ‘70s” with 100% more murder mystery and 100% less gay sex.

Critics were just as ambivalent about the film as festival audiences. While forward-thinking reviewers wanted to love it for its visual beauty and openly queer aesthetic, many lamented that its plot was slight and its characters hollow. David Ansen of Newsweek complained that “Haynes is unwilling to get too close to his characters. Slade, in particular, is a blank”—failing to see that Brian is a cypher by design. Like the Barbie-doll Karen Carpenter of Haynes’ debut feature, Superstar, and the fragments of Bob Dylan diffused across I’m Not There, Velvet Goldmine’s Bowie is less a portrait of the real person than a screen on which fans project their own fantasies about him.

At The Nation, Stuart Klawans rightly identified Arthur, not Brian, as the film’s protagonist. But he also wondered why he grows up to be such an unhappy adult. “Why is Haynes so tough on Arthur?” Klawans wanted to know. “Why, through the character, is he so tough on himself? It’s apparent everywhere in Velvet Goldmine that Haynes, like Arthur, loves Glitter Rock. He, too, fell for a mass-marketed product, which was no more likely than Mr. Clean to carry out a world-transforming promise. But instead of honoring the truth of his enthusiasm, so that he might look back on its object with a smile and a sigh…Haynes does penance for being a sap.”

Others found the film’s collage of ideas and allusions cumbersome. “Velvet Goldmine is weighed down with self-important messages, but it’s also splashily opulent,” Stephanie Zacharek wrote at Salon. “It’s as if Todd Haynes had plunged his hand into a pile of clothes at a jumble sale and come out with a handful that was half velvet finery, half polyester rejectables.”

All of these reactions make sense, coming from adult critics who had probably seen the film just once, after reading months’ worth of reports about its troubled birth, in the sterile environment of a press screening. But what’s clear from a distance of nearly two decades, during which Velvet Goldmine has become a low-key cult classic, is that few films are so poorly suited to be judged on the basis of a single dispassionate viewing. If you’re looking for tight plotting and complex characters, you’re not going to find them in this mixtape of music videos, aphorisms, and waking dream sequences. There is no actual murder mystery, and Arthur’s investigation into Slade’s disappearance isn’t a source of suspense so much as an excuse to keep contrasting an incandescent past with a dull, gray present.

I’m lucky enough to have first encountered Velvet Goldmine under what turned out to be ideal circumstances: at age 15, on premium cable, late enough at night that it easily bypassed my rational mind en route to my adolescent subconscious. I had no idea how many details it cribbed from the biographies of Bowie and his contemporaries, or how much of the dialogue was quoted from their (and their heroes’) most memorable utterances. I bought the soundtrack without realizing that it put ‘70s originals side-by-side with contemporary covers and new songs by younger bands like Pulp and Shudder to Think in yet another glam pastiche. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to find the 1984 scenes unsatisfying because I got so instantly immersed in the ‘70s spectacles that they barely existed for me.

Not that the film only works on an emotional level. Haynes’ ideas about fandom, politics, sexuality, and identity become even more profound once you can see the organizing principle behind what might initially seem like a jumble of indulgent images. Like the death hoax Brian Slade uses to escape a fantasy life that’s grown too real for comfort, Velvet Goldmine’s loose plot is classic misdirection, obscuring a tight and purposeful structure that delays the resolution of the ‘80s storyline until it’s primed you to feel the loss of the liberated ‘70s viscerally. But you’ll never get that far into dissecting the film if you don’t fall in love with it at first viewing. And that’s easiest to do when you’re as impressionable as young Arthur, who watches Brian Slade flaunt his queerness in a televised press conference and imagines himself shouting to his parents, “That is me!”

Revisit it as you grow older, though, and you might discover that the disillusioned 30-something characters now feel as rich as their idealistic former selves. Velvet Goldmine is often called a gay film, but that obscures the universal resonance of its queer coming-of-age narrative. Better to think of it as a bisexual film that uses non-binary sexuality as a metaphor for the boundless possibilities of youth—the promise of a future constrained only by the limits of one’s own ambitions and appetites. Its characters can’t achieve permanent liberation by “coming out”; to maintain lifestyles that match their desires, they would have to reject the monogamy that defines adulthood for most people. Particularly amid the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, which haunts the film’s dreary present on a purely subtextual level, it’s obvious why they (like the real glam rockers they’re modeled after) retreat from the liberated lives they staked out for themselves.

But you don’t need to buy in to the incendiary claim Brian makes at his press conference, that everyone is bisexual, to see how this storyline reflects the many kinds of disappointments that await most starry-eyed fans in adulthood. Klawans’ objection to Haynes’ treatment of Arthur feels naive because it assumes people should be able to peacefully coexist with their shattered dreams. Why shouldn’t he feel bitter about having joined a sexual revolution that didn’t, finally, set him free? “It gets better” for Arthur when he leaves his homophobic family to move in with a latter-day glam act in London, but sometime after he hooks up with an unmoored Curt Wild at a tribute concert called the Death of Glitter, “it” just gets boring as the world gets worse.

And the world really does sometimes get worse, though audiences in the relatively peaceful, prosperous late ‘90s might have forgotten about that. Watching Velvet Goldmine for perhaps the 25th time, two weeks before Donald Trump’s inauguration, at the end of an era that has brought unprecedented freedom of sexual and gender expression, I was struck by how vividly Haynes captures a culture’s flight from progress, and how rare it is to see that kind of transition depicted on film. His argument about fluidity turns out to be even more potent when applied to societies than individuals (or, at least, it seems that way in 2017). Our capacity for transformation may be infinite, but that doesn’t mean those changes are always for the best.

#todd haynes#velvet goldmine#ewan mcgregor#christian bale#jonathan rhys meyers#toni collette#michael feast#citizen kane#produced and abandoned#David Bowie#lou reed#oscar wilde#killer films#christine vachon#Musings#Oscilloscope Laboratories

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architecture film is "a genre in the making" as festivals multiply

Architecture film festivals are booming, as filmmakers turn their attention to the genre, new events launch, and audiences grow.

2017 has been a particularly standout year for film festivals dedicated to architecture, with new festivals opening in London and Melbourne, and already established ones adding more dates and cities to their programmes.

"I noticed that increase over a number of years," Kyle Bergman, founder of Architecture and Design Film Festival (ADFF) told Dezeen. "And now, since there's more and more festivals about it, there's more and more films actually being made on the subject, because there's a great audience for them."

Bergman already runs screenings in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York, which this year included a documentary about Australian architect Glenn Murcutt and a movie set among the modernist gems of Columbus in Indiana.

He will add Washington DC and San Diego to the ADFF festival roster for 2018. He said the popularity of architecture on film is "snowballing", with filmmakers being driven to produce by the demand for film festivals, and vice versa.

More festivals means more films, which means more festivals

ADFF started off in 2008. In addition to its solely architecture and design offerings, Bergman has also successfully lobbied larger film festivals such as the Chicago International Film Festival and Doc NYC to include sub-sections for architecture films.

"I think that really stems out of us showing, and other film festivals showing, that there is a real interest in this little niche," said Bergman.

"I'm not even sure it's established as a genre yet. But we're working on [it]," he added. "It's a genre in the making."

Across the Atlantic, London played host to the inaugural Archfilmfest in June 2017, a six-day festival exploring architecture through screenings, installations and workshops.

"To be honest I was really surprised there hadn't been one in London before we started. There's such an obvious relationship between architecture and filmmaking," the festival's co-director Charlotte Skene-Catling told Dezeen.

Related story

Movie protests demolition of Helmut Jahn's Thompson Center in Chicago

For Skene-Catling, the traditional drawings and renderings employed by architects had become staid in comparison to the avenues opened by employing cinematic techniques.

"Architects for so many years have represented buildings devoid of any kind of activity in them," she said. "People are always cartoon like or they are wiped out completely. Places are filmed or photographed completely empty. That's a very primitive approach to what architecture does."

Film can bring drama to architecture

Skene-Catling, the co-founder of architecture studio Skene Catling de la Peña, had been experimenting with using filmmaking in her practice and became fascinated with how the two overlap. She said film can push architects to design more exciting built environments.

"Buildings can be so incredibly powerful in creating an atmosphere. That's something that filmmakers seem to be more in control of than architects," said Skene-Catling. "There's so much architecture that exists at the moment that feels very devoid of atmosphere or emotion."

"Buildings need to have some of the drama of great films, so you have a beginning, a middle and an end. You have a series of events, you have drama, you have excitement, you have things that make your heart race," she said.

While architecture has played both a starring and supporting role in film since the medium began, technological advances have made it easier than ever to capture exciting and dramatic footage of the built environment.

Drone-mounted cameras have become particularly prevalent when it comes to capturing previously inaccessible shots, whether it's Hong Kong high-rises shot from above, Zaha Hadid's museum on a mountain-top, or footage of Robin Hood gardens pre-demolition.

Architects can learn from filmmakers

For its first London line-up, Archfilmfest functioned as a showcase for how buildings are sometimes more alive in the hands of filmmakers than the architects who first designed them.

Skene-Catling is keen to show that the symbiosis of architecture and film is very much the future. For students today, the boundary between the disciplines of architecture and film-making are increasingly fluid.

More universities are offering courses that train architects in filmmaking, and students are adopting new technologies such as CGI and 3D modelling with vigour. Of the seven students that the RIBA awarded its President's Medals to this year, three of the winners used short animated films as a central part of their project.

"They can start moving naturally between different disciplines. They have to become more fluid, more mobile," said Skene-Catling. "They have a way of strategising and diagramming, but also of representing ideas through visual media that includes film. That's very seductive, it's very convincing."

Established festivals keep getting bigger and better

In May and October, Sydney and Melbourne respectively hosted film and documentary screens alongside panel discussions, as part of ArchiFlix festival.

The success of this year's ArchiFlix, which was founded by business developer Sally Darling and producer Ron Brown in 2013, will see the programme expanded to include three-day festivals in Perth and Brisbane, along with the four-day festivals in Melbourne and Sydney, and satellite events in Adelaide and Hobart.

"The first ArchiFlix film night was held in 2013, with the audience demonstrating a real thirst for the inspiration and storytelling of architectural documentaries," Darling told Dezeen. "After a couple of years of these one night events, I felt the industry was ready for a festival."

The pair are set to launch ArchiFlixTV in the near future, offering a global streaming platform solely for architectural films.

Related story

Architecture at its best is "pure fiction" says Bjarke Ingels in new Netflix documentary

While ADFF, Archfilmfest and ArchiFlix are relative new-comers and fast growing in the world of architecture film festivals, more established film festivals continue to go from strength to strength, as enthusiasm and awareness for this putative genre grows.

Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam (AFFR) was established as a biannual architecture film festival in 2000, with a particular focus on architecture, film and the city.

In 2007, after a brief hiatus, the AFFR came back with a bigger programme than ever, with each edition centred on a theme exploring architecture and urbanism. Past themes include Think Big, Act Small, Time Machine, and City for Sale.

The 2017 AFFR was so successful that the organisers announced earlier this month that the festival would become annual instead of biannual. AFFR 2018 will be its 10th edition, and the foundation that runs it also organises screenings and events throughout the year.

Budapest Architecture Film Days was started in 2008 after its founders, already keen to bring the conversation around architecture and film to Central Europe, were spurred on by an encounter with AFFR co-director Jord den Hollander.

"He was very supportive of the idea of establishing a similar festival in this region," spokesperson Gábor Fehér told Dezeen.

Architecture films are alerting people to urban issues

Now in its 10th year, Budapest Architecture Film Days is organised by KÉK, the Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Centre, which is an independent organisation run by young architects and artists.

They chose film as a medium for its broad appeal, hoping to attract as wide an audience as possible.

"Our motto 'Do you live in a building? Do you watch movies? Good reasons to join us!' perfectly captures the principle behind the festival," said Fehér.

"[We're] making use of the medium of film as an egalitarian tool to converge people towards the topics of not just architecture, but also to various issues surrounding urban conditions and communities, neighbourhoods, and living spaces."

When they started out, awareness of how architecture and film could interact was limited. The first festival was held in a single room in KÉK's former headquarters.

Since then the venue has been Toldi, an art cinema with 250 seats. Today screenings are often fully booked out, prompting the festival to hold multiple showings.

As the audience has grown, so too has the number of films being made. Fehér has also noticed a growing trend for longer architecture films being made, suggesting filmmakers have more time and resources to dedicate to the subject of architecture.

"We are receiving more and more submissions each year to our annual call for films from filmmakers all over the globe," he said. "The cinematic scene of architecture and design is definitely going strong."

It all began in Florence

Marco Brizzi founded what was arguably the world's architecture film festival in 1997, which was Florence's Beyond Media event.

Beyond Media charted the new ways in which architecture and audiovisual tools were being created in relation to each other. Over nine editions, it documented how architecture and the media interacted.

The Florentine festival ran until 2009, spanning a period of immense change for the media and a time of rapid technological advances in filmmaking.

Screenings were at its core, with past line-ups including early videos from architecture notables such as UNStudio, MDRDV, Rem Koolhaas and the late Zaha Hadid.

The online audience for architecture films is also booming

Online, people can't get enough of architecture on video. Dezeen's total video views across all platforms have doubled to 60 million from last year, with a series on moving buildings racking up 17 million views on Facebook alone.

Netflix has been getting in the act too. Earlier this year the digital streaming service launched an eight-part series of documentaries profiling big names from the world of architecture, including BIG's Bjarke Ingels.

Architects have been enjoying their fair share of the spotlight too. Last year Dezeen sat down with Tomas Koolhaas to discuss his film REM, which was the result of following his superstar architect father around the world for four years.

Related story

Rem Koolhaas "doesn’t respond well to having a lens shoved in his face" says his movie-maker son

Photograph is by Fabio Duma.

The post Architecture film is "a genre in the making" as festivals multiply appeared first on Dezeen.

from ifttt-furniture https://www.dezeen.com/2017/12/22/architecture-film-movies-genre-in-the-making-festivals-multiply/

0 notes

Text

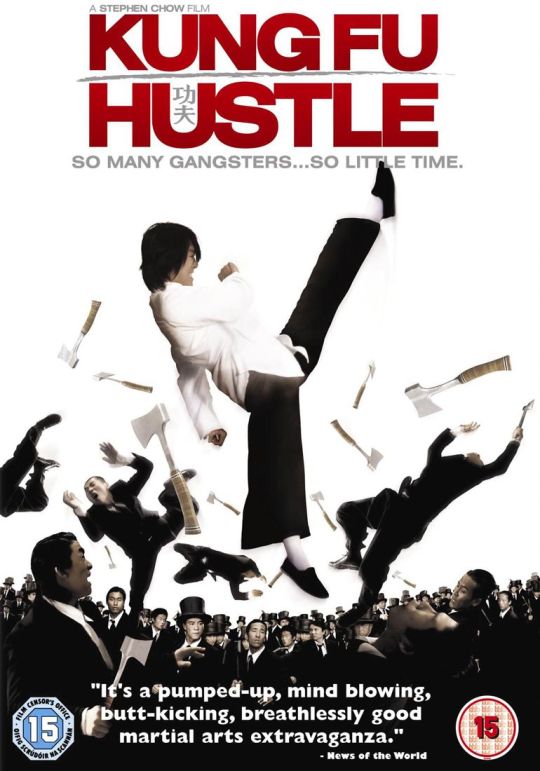

KUNG FU HUSTLE– EXEMPLAR OF A GLOBALIZED ASIAN POPULAR CULTURE PRODUCT

“I don’t feel that I am leaving Asia at the moment.” – thought I. After 2 months moving to Melbourne, yet, I haven’t any sense that Asia is thousands of kilometers away from me. I saw Asians everywhere in Melbourne: they speak Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, etc. I saw Asian languages on street banners and shop signs. I noticed posters and billboards of Asian movies hanging here and there. It seems the continent is ‘expanding’. This expansion does not take a physical shape, but it comes under the form of culture. To prove that Asia and its popular culture are ‘evading’ the earth, I will examine factors that lead to the success of Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle film.

Stephen Chow (Chow Sing-chi) is a Hong Kong film director, actor, producer and playwright. He is well-known in Asia region for his comedies such as Kung Fu Hustle (KFH), Shaolin Soccer, and CJ7. The director remarks his sense of humors through over 50 films across Hong Kong, China mainland and regional countries such as Vietnam, Korea, and Singapore. However, only when KFH was released, could Stephen Chow realize his ambition to make his films go global. In KFH, he adopted a different scheme in film production and distribution to ensure the movie can reach beyond Asia to the America market.

Stephen Chow’s films always retain a commercial sense. Consistently in his screening career, Chow depicts the demotic character as an artful underdog who gradually cultivates recognition with his ability (for example his sharp tongue) (Klein 2007). In KFH case, Sing – the main character who used to wish to become a villain – finally uncovers his goodness and martial-art potentials. He later earns respect from his community by defeating Beast. This pattern in Chow’s film matches Frankfurt School perspective on culture: culture is determined by the production and organization of material existence (Donnar 2017). Hence, in this point of view, popular culture refers to mass culture, massively produced, commodified and standardized. How did Stephen Chow produce his film to satisfy the taste of the broad global market? Did the economic and political environment contribute to KFH’s success worldwide?

The foremost reason for the KFH success undeniably comes from Stephen Chow himself. First, it is his pastiche technique in script writing and acting. Pastiche technique is the imitation of style and or character of the work of one or more other artists to celebrate rather than mock (Hoesterey 2001; Preminger, Warnke & Hardison Jr 2015). He recycled his comic bits from previous films such as God of Gamblers III, Chinese Odyssey I, Forbidden City Cop. Chow built Sing – his main martial-art character – with characteristics and actions that evoke audience mind images of the two famous martial arts figures from both the East and West, Bruce Lee and Keanu Reeves’ Neo (Klein 2007). Sing’s final fight with the Axe Gang imitates the fight between Neo and hundreds of Agent Smiths in The Matrix; during the fight, Sing wears the costume same as Bruce Lee in Enter The Dragon (Szeto 2007).

Second, Chow incorporated Western cultural references within his movie to target American box office. For example, when Donut (a supporting character) dies, he says, ‘In great power lies great responsibility’, a reference to Spider Man, said by Uncle Ben before his death. Explaining his pastique technique and Western culture inclusion, he said “I wanted to capture the mass audience from the start.” (Walsh 2003) Thanks to that combination, Stephen Chow successfully made KFH relatable to both domestic market and Hollywood market.

Next, external factors also contributed to Chow’s KFH success. Among those, globalization trend in film industry is one of the most significant. According to Steger (2003), globalization enables the creation of new and multiplication of existing social networks and activities that overcome traditional, political, economic, cultural and geographic boundaries. It also involves the intensification and acceleration of social exchanges and activities. Audiences from around the world have been familiar with Hollywood blockbusters about Western society, but rarely seen those of the Eastern one. They, especially U.S audiences, are getting bored with Hollywood plots. Thus, we are seeing more and more co-production of Chinese-American movies in order to quench the audience’s thirst for something new and erotic (Masters 2013). Understanding this, Stephen adopted this social exchanges of globalization in his film production by partnering with Columbia Pictures (an American film studio that is a member of Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group) from the beginning of idea formation. This studio then funded Chow 95% of his cost to produce the movie. 5% left came from sponsorship of 2 mainland partner studios: China Film Group and Huayi Brothers & Taihe Film Investment (Klein 2007).

With Columbia Pictures’ co-production, Chow refined his script to a very detailed and up-to-Hollywood standard: narratively consistent with logical events and without irrelevant scenes. This was very peculiar to Hong Kong usually rough and loosely edited script (Klein 2007). This co-production opportunity offered Chow the best human resources. For instance, his sound engineering team comprises famous sound designers like Steve Burgess who designed sound for Moulin Rouge and Bruce Emery – sound designers of King Kong, Lords of the Ring, The Hobbit. Finally, Columbia Pictures had the responsibilities for film marketing and distribution worldwide, targeting at the world largest box office – U.S.A. Chow’s mainland partners did not only provide shooting locations, but they also helped the film pass the strict censorship in China and penetrate into the domestic market. With all those supports, in total, the film made the worldwide box office of over 102 million dollars (The numbers n.d.). The movie became the highest-grossing Chinese-language film in the history of Hong Kong until 2011 and the all-time tenth highest-grossing foreign language film in the United States as well as the highest-grossing foreign language film in the country in 2005.

Another crucial external factors that led to KFH’s success is the soft power practice in China. The idea of soft power was developed by American political scientist Joseph Nye who argues “country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries—admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness—want to follow it.” He further suggests that one of the resources for the exercise of soft power is culture (Nye 2004). The Chinese soft power allows foreign co-production, ejecting more financial resources to a weakening film industry (Chua 2012). “I think they have a real ambition to build up a film industry, a real studio business,” Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton expressed his opinion of the Chinese agenda in dealing with American studios to create their own version of Hollywood (Masters 2013). As demonstrated above, KFH benefited a lot from this condition as it received up to 95% foreign investment and 100% global marketing and distribution effort. Furthermore, the 2003 Closer Economic Partnership Agreement has significantly reduced the barriers to Hong Kong pop culture crossing into China. The partnership allows Hong Kong films, even co-productions, to be identified as domestic Chinese release, excluding from the foreign films segment. Hence, KFH was recognized as a Chinese movie before it circulated over the world. Soft power, in this case, solved the problem of investment shortage and paved a clear pathway for Chinese culture to expand over the world.

In conclusion, Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle is an exemplar of Asia Popular Culture Product that successfully went global. Thanks to his talents, pastique technique and Western culture allusion, the film appeals to both domestic market and the targeted Hollywood market. In terms of external conditions, globalization brought about co-production between Columbia Pictures and Chow, giving him all favorable prerequisites to make his name and his film world-known. Moreover, without Chinese soft power practice, Kung Fu Hustle would not have been a phenomenon of the Chinese-American movie, which sat as the highest-grossing Chinese-language film in the history of Hong Kong.

REFERENCES

Chua, BH 2012, Structure, Audience and Soft Power in East Asian Pop Culture, Desiring Hong Kong, Consuming South China, Hong Kong University Press, HKU, Hong Kong.

Department of Chinese Literature - Sun-Yat-Sen University 2005, ‘從金剛腿到如���神掌—論《功夫》(From the Steel Leg to Ru Lai Shen Zhang, Kung Fu Hustle)’, Department of Chinese Literature NSYSY, viewed 22 Aug 2017, <http://www.chinese.nsysu.edu.tw/932chp/article/f04.htm?lang=en&Trad2Simp=n>.

Donnar, G 2017, ‘Lecture 2_Asian Pop Culture_2017’, course notes for COMM2345 Exploring Asian popular culture, RMIT University, Melbourne, viewed 20 August 2017, Blackboard@RMIT.

Hoesterey, I 2001, Pastiche: cultural memory in art, film, literature, Indiana University Press.

Klein, C 2007, 'Kung Fu Hustle: Transnational production and the global Chinese-language film', Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 189-208.

Nye, JS 2004, Soft power: The means to success in world politics, PublicAffairs.

Preminger, A, Warnke, FJ & Hardison Jr, OB 2015, Princeton encyclopedia of poetry and poetics, Princeton University Press.

Steger, M 2003, Globalization : A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK).

Szeto, K-Y 2007, 'The Politics of Historiography in Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle', Jump Cut, vol. 49.

Walsh, B. (2003), ‘Stephen Chow,’ Time Asia, 28 April, viewed 23 Aug 2017 <www.time.com/time/ asia/2003/heroes/stephen_chow.html>.

0 notes