#modern domestic life with thoma . . . . . . .. .

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley (l. c. 1753-1784) was the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry and become recognized as a poet, overcoming the prevailing understanding of the time that a Black person was incapable of writing, much less writing poetry and, further, that an enslaved person, considered property, could do so.

She was not, as commonly claimed, the first African American author to publish poetry, as that distinction goes to Jupiter Hammon (l. 1711-1806), who published his An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries in 1761. Wheatley, however, holds the honor of being the first African American author to publish a full-length book of poetry, her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, in 1773.

Her book was widely praised both in England (where it was published) and in Britain's North American colonies. She received a personal response from General George Washington (l. 1732-1799) thanking her for a poem she had written in his honor in 1775, which was later published by Thomas Paine (l. 1737-1809) in the Pennsylvania Gazette.

Not everyone was a fan of Wheatley's works, however, and some, most notably Thomas Jefferson (l. 1743-1826), dismissed her as simply a mimic who was only capable of reflecting concepts she had absorbed from White classical writers. The backward views of Jefferson, and those like him, did nothing to diminish popular appreciation for Wheatley's work, however, and she remained highly regarded, even after falling on hard times, until her death at the age of 31.

Today, Phillis Wheatley is regarded as one of the greatest American poets and continues to be honored as such through place names, memorials, plaques, and educational institutions.

Life & Work

Wheatley's brief biography, as given by L. Maria Child and included in Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction (1926), compiled and edited by Hallie Q. Brown, is given below, although some details are omitted, which will be addressed here.

Phillis Wheatley's actual name is unknown. She is thought to have been born c. 1753 in modern-day Gambia or Senegal and was one of the over three million people of those regions sold into slavery. She arrived in Boston, Massachusetts, aboard the slave ship Phillis in July 1761 and was purchased by John Wheatley, a wealthy merchant, and his wife Susanna. The Wheatleys named her after the ship that had brought her to them.

The Wheatleys had two children, twins, Mary and Nathaniel, who were then 18 years old. Mary taught young Phillis English and how to read and write, while Nathaniel assisted as his duties would allow. Phillis was a fast learner, and by the age of 12, was proficient in Greek, Latin, and the Bible. She wrote her first poem when she was 14, and, that same year, published another poem, on the near wreck of a merchant ship caught in a storm, in The Newport Mercury on 21 December 1767.

Although a slave, Phillis was treated like a member of the family and given light domestic work. The Wheatleys were progressive members of Boston society and, recognizing the girl's innate intelligence and quick wit, encouraged her education. She would frequently be invited to dinner parties given at the home to read her latest works, which were met with praise and gave her the confidence to write more.

By 1773, Phillis had a book-length manuscript of verse, and Susanna sent her to London, accompanied by Nathaniel, who was traveling there on family business, because she felt there were better chances of finding a publisher there than in the Colony of Massachusetts. Phillis had also been told by the family's doctor that she should avail herself of a sea voyage for her health as she suffered from asthma and a frail constitution.

Through Nathaniel's connections, Phillis was introduced to the members of high society in London, including the Lord Mayor, Frederick Bull. News of the young African poet circulated quickly, and Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, agreed to be her patron without ever having even met her. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published 1 September 1773.

An audience was arranged with King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820), but news arrived that Susanna Wheatley was seriously ill, and Phillis and Nathaniel left for Boston before she could be presented to the king. Upon her arrival home, the Wheatleys set her free, and she cared for Susanna during her illness until her death in the spring of 1774. John died in 1778, and Mary soon after. Nathaniel moved to London to manage the business there, and Phillis was left alone in Boston.

She found work as a domestic before meeting the free Black grocer, John Peters, whom she married. The couple lived in poverty, and their two children died in infancy. Peters' business failed, and when he could not pay his debts, he was sent to prison in 1784.

Phillis was left alone again, this time with a third infant child, and found work as a scullery maid. Never very robust, Wheatley developed pneumonia and died on 5 December 1784, along with her infant daughter.

Read More

⇒ Phillis Wheatley

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liam being bi again, let's not ignore it

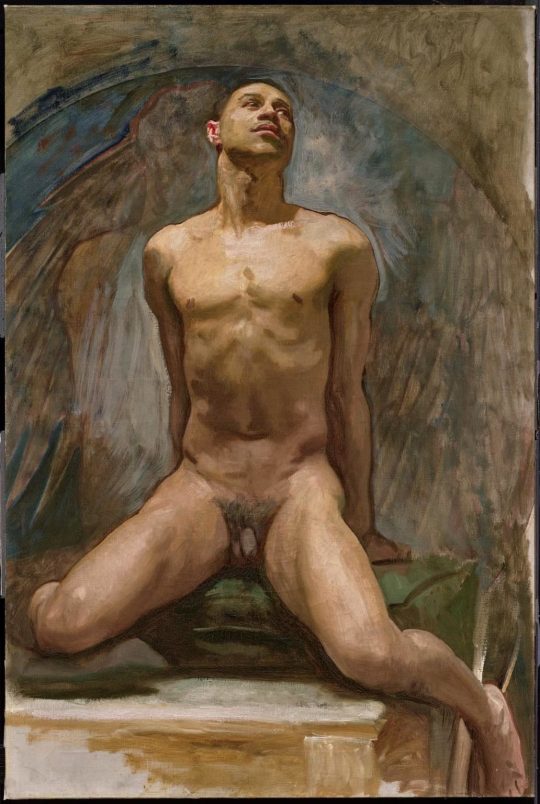

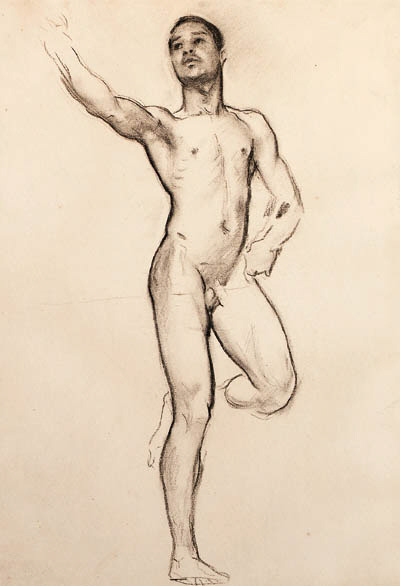

On his IG live on 7.8.23, Liam said John Singer Sargent is his favorite artist. Sargent's sexuality is heavily debated; modern interpretations are that he was likely gay - at minimum, much more an admirer of the male figure than the female.

Sargent never married, was intensely private about his personal life. X He was a neighbor to Oscar Wilde and would have been very aware of his trial.

Sargent's paintings are often considered homoerotic or "remarking on the fluidity of human sexuality."

Many of his works are sensual portraits of well-built men in generally feminine poses - arched backs, heads thrown back in passion, etc.

His muse was Thomas Eugene McKellar, a Black bellhop at a posh Boston hotel. Every figure - both women and men - in Sargent's mural at the Boston Museum of Fine Art's rotunda - is McKellar's face - though with his race obscured, and who was paid only a small amount.

He also created many other images of McKellar, one of which he exhibited in his studio his entire life but never showed in an exhibit.

McKellar's family have said they suspected he was gay, and that's why he moved away to Boston.

Some of Sargent's contemporaries remarked about him having many trysts with men when he traveled to Venice and Paris, with a preference for men with darker hair and skin.

Andy Warhol named Sargent as one of his inspirations. Sargent's mural of Hell for the Boston Public Library is thought of as some of his least sensual work - yet when Warhol first saw it, he referred to it as a "gang bang."

On his IG live Liam also read a username that referred to Timothee Chalamet, and before answering the question, he remarked on his attractiveness, twice.

A few days earlier, Liam posted two photos on Instagram of him meeting British artist David Hockney who he called his "inspiration and idol." Hockney is LGBTQ and is known for his intimate portraits of gay domesticity:

Here is a video of Hockney talking about Harry asking to be painted by him and someone please link the masterpost about Harry queer coding through talking about Hockney.

I'd say Lima mildly flirted with Mark Wahlberg in his thirst trap IG photo comments also x

Besides Ziam, my favorite bi liam content here x

#bi bi bi#bi liam payne#liam payne#queer coding#Liam's sexuality#not even gonna mention ziam in the post#john singer sargent#andy warhol#david hockney#Thomas Eugene McKellar#lgbtq artist#lgbtq artwork#7.8.23

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Janan Ganesh: Next week, when Donald Trump strokes a Bible and requests the help of God as president, even a large share of his own fans will doubt that he means either gesture. Thirty-eight per cent of them, as well as most Americans in general, have him down as “not too” or “not at all” religious. I won’t presume to know the inner life of a stranger. But as far as the public is concerned, the US has had, and is about to have again, a leader who is at least atheist-adjacent. Within my lifetime, this was unthinkable.

It is worth pausing to mark little liberal wins, such as the creeping secularisation of the most important country on Earth. Seventy per cent of Americans were members of a place of worship as recently as the millennium. Now fewer than half are. The religious right, while still a force, as Dobbs showed, has to be more covert and euphemistic than it was under Reagan or either Bush. Trump keeps the agents of God around him, no doubt. But on what a tellingly short leash.

A liberal looking for some shards of light in the general murk doesn’t have to make do with this. Here is another intellectual victory so total and pervasive that it tends to pass without notice:

When was the last time someone suggested “de-growth”, and received a hearing? When did it last seem deep and clever to name “wellbeing” as something that should displace gross domestic product? Pre-Covid? Almost everyone in public life now has to pay at least lip service to economic growth: in Europe, which doesn’t have enough, in the US, which does and wants more, in India, which hopes to be a rich country by 2047. Trump keeps the agents of God around him, no doubt. But on what a tellingly short leash

“It’s time we admitted there’s more to life than money,” said David Cameron, who grew up in a rectory, though which wing of it he favoured I don’t know. A prime minister who spoke that sentence in public now wouldn’t see out the week. There is nothing like economic stagnation to teach a country that anything you might rate above money — the preservation of nature, universal access to art, leisure time for relationships — itself depends on surplus income. GDP, while not everything, is almost everything. The priorities of liberal capitalism are harder to question than in the very recent past.

And even this isn’t the ultimate fillip for we who believe in that cause. Five winters ago, news of a viral pandemic started to trickle through. When the lockdown began, I thought it would be 2025 before tourism, nightlife and the ambient sound of cars would come back in full. Other people I thought I knew well hoped that it would be longer. There is a romantic and almost medieval distaste for modern life that simmers away in societies that have been rich for a long time. It isn’t confined to nature-is-healing airheads. It drove TE Lawrence to the desert, and enamoured George Kennan of pre-industrial Russia.

Well, it lost. My prediction was pessimistic by, what, three years? Tourism is rife. I can’t get a table at Goodbye Horses. New York has introduced a congestion charge. In the end, as soon as restrictions eased, people voted with their feet for liberal modernity, even if few of them would think to call it that.

One of the dangers of being excessively online is that you over-index small-time “trends”. Yes, quack science is spreading. This or that gasbag reactionary has two million followers. But these things have to be set against larger defeats for the superstitious, the nostalgic and the anti-modern: defeats so structural as to be hard to spot.

In retrospect, it was a deceptively civilised moment when Trump couldn’t name his favourite Bible verse during a TV interview. (“I don’t want to get into specifics.”) Thomas Jefferson had to go through brilliant circumlocutions to pass off his beliefs as something mistakable as Christian faith. It is possible that one or two recent presidents have slyly padded out whatever quantum of religious feeling dwelt inside them. Now? Going through the motions is enough. Like no other modern figure, Trump shows that liberalism is beleaguered, and quietly rampant.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Escaped/Modern DBD A/B/O AU - “A Pack’s Harmony”

Chapter 1: “Shaky Assimilation”

Word Count: 3,739

Other Posts Regarding This Fic: ☾ ❀ ✮ ♚

After years of tortuous trials and countless attempts at fleeing, the survivors and killers finally found a breakthrough in the growing instability of the collapsing realm. With the unexpected help from the FBI — as they had been observing the unnatural phenomenon for years — the extensively trained agents immediately jumped into action once the victims made it to the other side. Finally free from that hellish, cold, dark realm, the FBI came to their aid, providing shelter, protection, and life necessities to the victims.

The federal agents chose very few, specific killers to rescue, a true Hail Mary with their rehabilitation attempts. Most other killers were deemed unsafe to come out of the phenomenon, and others were sadly believed to be beyond repair. The FBI keeps the killers and survivors separate with their housing arrangements, not wanting to cause any possible altercations. Yet, they all live in the same, fenced-up, small, secluded cul-de-sac.

Not far apart, the killers and survivors were simply just across the road from each other, surprisingly — for the most part — getting along rather well. The government desperately tried to keep the group contained and hidden away from the public, still undergoing studies and tests on them to test for any abnormalities. Once passed through the tests — however long that would take — they *could* have the possibility of leaving this controlled environment, moving to a normal location instead. Though, that wasn’t expected to happen any time soon.

In their first day of freedom, a few of the domestic agents worked together with the victims, trying to get their living arrangements in writing. Giving them a day of downtime before beginning to conduct their series of medical tests. Allowing for each individual to speak up on their housing preferences, many immediately chose to bunk with a specific person/group, while others just seemed too baffled to even answer the question.

Getting what they could out of everyone, the housing arrangements were decided…at least for now. Leading everyone to their respective houses, they had everything in writing:

- Survivor house arrangements -

• House 1: Claudette Morel, Meg Thomas, Dwight Fairfield, and Jake Park. (Per all individuals’ requests.)

• House 2: Mikaela Reid, Sable Ward, Feng Min, and Nea Karlsson. (Per 2 individuals’ requests.)

• House 3: Haddie Kaur, Kate Denson, Yun-Jin Lee, Yui Kimura, and Zarina Kassir. (Per 2 individuals’ requests.)

• House 4: Jane Romero, Élodie Rakoto, Thalita Lyra, and Renato Lyra. (Per 2 individuals’ requests.)

• House 5: David King, Vittorio Toscano, Gabriel Soma, and Jeff Johansen.

• House 6: Ace Visconti, Adam Francis, Felix Richter, and Jonah Vasquez.

- Killer house arrangements -

• House 7: Susie Lavoie, Julie Kostenko, Frank Morrison, and Joey. (Per all individuals’ requests.)

• House 8: Max Thompson Jr. and Philip Ojomo. (Per 1 individual's request.)

• House 9: Anna, Sally Smithson, and Carmina Mora. (Per all individuals’ requests.)

—

As everyone was freshly showered and well rested for the first time in forever, they were awoken to a surprise of multiple doctors scattered across their limited yard. Temporary medical tents were even set up, stock full of countless, expensive supplies. Carmina had already beaten everyone else to the tents — besides Anna and Sally, who had pushed her here in the wheelchair — hooked up to a few IVs and surrounded by soft-tempered doctors.

Inspecting the poor woman’s missing, crucial limbs, it was obvious prosthetics would quickly need to be made and fitted to her, which meant physical therapy would also be necessary. They were just thankful for the girl’s compliance, getting fluids and numbing medication flowing through her system while she lay and relaxed. There was little enjoyment to be had in life when you were missing your arms *and* legs, pushing the professionals to speed up their prosthetic building process, wanting to give this girl her life back.

Determined to fully observe each little detail of the group after coming from such an unexplainable phenomenon, each person was mandated to undergo a series of medical exams. Blood tests, physical exams, and, of course, DNA tests. It was not only to examine the body’s possible reaction to their previous experiences, but also to test for their secondary genders. Each person was going to be provided therapy and support groups in correspondence to their secondary genders. These individuals were just victims after all, and the agents didn’t mind extending a supporting hand out to help them step closer towards the integration of the new world.

While going through their lengthy line of medical checks, the professionals were met with a few uncertain, reluctant people, yet they all eventually agreed and complied. However, making their way to a particular redhead who had previously been so kind and cooperative with the other tests, they were shocked by her sudden, blatant refusal. Getting unexpectedly snippy and short with the patient staff, Meg refused the mouth swab. “Yeah, no thanks.” Stepping back away from the medical personnel, she crossed her arms over her chest, careful not to bump her bandage from recent blood drawing.

Holding the swab with confused, furrowed brows, the female doctor was at a bit of a loss. No one else had refused yet, and she didn’t quite know how to gently handle the situation from here. Glancing down at the medical paper on her side table, the woman tried to jog her memory with Meg’s name. “Ms. Thomas, this is a mandatory test.” Going above and beyond to be kind and patient with the girl, the doctor smiled, trying to reassure her — just in case the redhead was ‘afraid’ of the test. “It’s a simple swab. No needles are required; it’s painless, and the labs are run off-site afterwards. It takes just a second.”

As if the girl hadn’t listened to a word the doctor said, Meg immediately shook her head in response, continuing to keep her distance. “Once again: no thanks. I’m not concerned about the test, I just want to opt out.” Looking over at the woman trying her best to stay patient, the redhead continued. “I’m a beta. I went through the test when I was a teen; you can just write that down.”

A bit baffled with such a bold display, the professional momentarily paused. “I’m sorry, but this isn’t an optional test you can ‘opt out’ of. This is actually being requested by the FBI, Thomas.” With her smile beginning to waver ever so slightly, her voice remained soft and comforting. “This is no longer an average, domestic checkup that you’re used to.”

Despite the doctor trying her best to remain kind and patient, Meg trampled all over her gentle performance. “I’m a beta, just write it down.” Glancing down at her paper on the table then back to the kind doctor, Meg gave a short, somewhat sarcastic smile. “Have a great day, ma’am.” Abruptly walking away from the doctor and out of the medical tent, Meg left the baffled professional to herself.

The doctor’s smile dropped after the interaction, hesitantly filling out the redhead’s paperwork. Whether it was actually correct or not, the woman didn’t know. Setting the pencil down, she flipped to the next paper, once again putting on a smile, calling up her next patient. “Karlsson?”

Outside of the tent, Meg’s smile suddenly turned sincere when meeting back up with Claudette again. The girl stood out in the green plains that surrounded their enclosed, FBI-controlled cul-de-sac, gently prodding at the bandage wrapped around the bend of her arm. “Claud, how are you feeling?” Smiling, Meg looked down at the nervous girl, watching her umber eyes immediately shoot up to meet her own emerald orbs.

A smile quickly overtook her once-so-nervous face. “Oh, Meg.” Softly speaking up, the girl lowered her restless, prodding hand. “I’m feeling alright.” Glancing back to the tent behind the redhead, Claudette had just come from that station: the DNA testing. Meg had previously confessed about her true secondary gender to the botanist before, during one insomnia-ridden night at the campfire. The redhead was so ashamed and afraid of being labeled a ‘monster.’ It only led the girl to wonder…how did that interaction go? “Did you give the staff any trouble?”

Running a hand through her soft, clean hair, Meg toyed with her curly ponytail. Stretching a bit, the woman arched her back before abruptly stopping with Claudette speaking up. “Well, no..? Not *technically*?” Smiling sheepishly, the athletic woman knew how ‘disappointed’ the soft-tempered girl would have been to know her full dismissive attitude toward the generous medical staff. A little fib to keep the girl happy wouldn’t hurt, right? “They didn’t get the sample, but I wasn’t rude to anyone.”

With a soft smile and unsure eyes, Claudette’s gaze slowly drifted away from Meg, just hoping she was being truthful. Stepping a bit closer to her redhead counterpart, the girl rested her head gently against the woman’s arm, looking around the busy yard.

Thalita and Renato sat in a tent together, the sister getting her blood drawn, while the younger brother stood close by, taking the familiar hand into his own. It settled his nerves to be close to family like this.

The ‘Legion’ — if it were even proper to call them that anymore — were huddled together like usual. With each test, the teens stayed in a group, causing the doctors to trade paperwork, as the teens were picky to stay together. They couldn’t even blame the poor kids either; this was a truly nerve-wracking experience, and it was only reasonable to stick close.

Glancing over, Claudette noticed Philip and Max still in a tent themselves. The lanky, concerningly emaciated man was hooked up to an IV, getting easy nutrients directly into his body. Beside him was Max, undergoing a physical examination with his severe fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, trying to find the right treatment and medication to proceed. Due to the excess bone structure, surgery was useless, as it was common for more bone formations to just reform in the place of removal.

Although many others were already finished with their tests — in their respective houses, relaxing — Claudette’s attention was directed to the tent with Anna, Sally, and Carmina. The three of them had been there for hours, especially Sally, not wanting to leave Carmina’s side. Doctors continued to aid the quadruple amputee, making rushed molds and casts of the temporary sockets. Although these prosthetics weren’t going to be anything long-term, they were still crucial to creating the eventual, permanent prosthetics for the woman.

Every prosthetic involved the tedious trial and error process. Wrong size. Wrong length. The socket too loose. The socket too tight. The finicky creation was a long one. Giving the girl her first set of prosthetics, the doctors didn’t expect her to use them right away, nor did they want her to. A recovery like this would need months of physical therapy, but eventually she would get to a happier point. Carmina was just grateful to have both Anna and Sally at her side, ready to help at every turn.

—

Returning to their home, butterflies briefly fluttered in Claudette’s stomach. Entering *her house*, that just sounded so nice… She severely missed having a safe place to relax. With the two girls walking in to a quiet TV playing, they were promptly greeted by Dwight’s soft, yet enthusiastic voice. “Welcome back! We had some food supplies delivered while you two were out. I’ve already put it away in the kitchen, have a look if you’d like.” Smiling with his usual, cute, dorky face, it was thoughtful of the man to put everything away, given the girls had been busy and Jake was trying to mellow out.

The introverted, softhearted man was all wrapped up in a soft blanket, curled up on a separate loveseat in the corner of the living room. Upon their arrival and Dwight’s soft greeting, Jake curiously peeked past his blanket, dark orbs landing on the other two. In his own form of greeting, he gave a slight, silent wave accompanied by a smile, staying underneath his blanket. The man struggled with overstimulation and overwhelming situations. The past two days had been a lot for him, leaving him quiet and to himself. It was his own comforting reset of sorts, just trying to fill that social battery back up. There was no shame in bowing out of the action for a second.

Giving a soft smile to her new housemates, Claudette’s umber eyes respectfully drifted to both Dwight and Jake, giving them their equal acknowledgment. “Thank you, Dwight.” Sincere in her gentle gratitude, the botanist curiously eyed the kitchen — just beyond the living room’s farthest wall. “We’ll go check it out.” Giving one last, soft glance to Dwight and Jake, Claudette entered their kitchen, with Meg following behind, like a dog at her heels.

Curiously looking through the cupboards — relieved to see fulfilling snacks and *actual* food for the first time in a long while — Meg’s blue eyes would occasionally drift back, peeking over her shoulder to Claudette. Watching the short girl look through the drawers with a smile, the redhead couldn’t help but smile along herself. It all felt so domestic and warm, like they were truly living a normal, happy life together… If you ignored their small, fenced-in, FBI-controlled cul-de-sac in the middle of — seemingly — nowhere.

Looking back to the cupboards, Meg quietly shut the doors, spinning on her heels, turning to face Claudette. “Hey Claud.” Speaking up, the energetic woman lifted her arm, prodding at the medical gauze wrapped around the bend of her arm. “You’re the smart one; can I take this off yet?” With a teasingly playful tone, Meg gave the girl a cute smile.

Interrupted in the middle of her looking, Claudette curiously turned her head as her nickname was spoken. Glancing back to Meg, the bespectacled girl raised a brow at the woman’s provokingly worded question. “This should be a very simple answer, Meg.” Playfully responding, Claudette turned around, smiling as she faced the redhead. “Has it been thirty minutes since your blood was drawn?” Teasing right back, the botanist awaited a response.

Meg’s heart nearly skipped a beat with Claudette’s sweet smile and cute, reciprocated teases. However, fighting off the admiration, the woman kept their playful conversation’s energy. Pausing for a second, her blue eyes curiously landed on a nearby clock, slightly askew on the wall. “…I *think?*” Meeting back with the girl’s own dark eyes, Meg’s smile remained soft and playful.

Glancing down to Meg’s gauze with a nod after her answer, Claudette tilted her head and softly gestured towards the medical wrap. “Congratulations, you just answered your own question.” Teasing the athletic woman once more, the shorter girl’s smile remained honest and sweet. “You’re allowed to remove it now.” Lifting the teasing tone a bit, Claudette gave a genuine answer, actually beginning to unwrap her own. Honestly, after everything that happened today, the girl had forgotten all about the gauze band.

—

While these particular housemates were getting along exceptionally well — as the four had all chosen to bunk together — the next house over, dubbed ‘house 2’ was…a bit of a different story. Sable and Mikaela had chosen to bunk together; however, Nea and Feng were both randomly selected to fill the empty spaces. They didn’t mind the other housemates…until they did.

Feng could be rather picky or specific at times, though for the most part remaining respectful. But, Nea? Completely different story; the girl seemed incredibly angsty, entitled, and territorial. While it had only been a day together, anything could change as they settled in. Sable was just riding on that hope, while Mikaela was instead already trying to cope with their housing arrangement.

When it came to choosing housemates, Haddie and Yui immediately banded together. The two had grown quite friendly with each other during their time in the fog, so it was only natural that they would choose to stick together. Without further preferences mentioned, the two girls were randomly placed in ‘house 3’ with Kate, Yun-Jin, and Zarina. A house of girls didn’t seem like a bad thing at first; however, their attitudes and secondary genders were definitely going to be a tough challenge to overcome.

Yun seemed to be easily annoyed, with Kate already getting on her nerves; in return, Zarina couldn’t stand Yun’s constant, teetering mood. However, surprisingly, the ex-producer did happen to get along with at least one of her housemates: Yui. This was likely due to their similar dominant personalities, as most of the more dominant pack members tightly banded together.

In ‘house 4’ was a unique setup and interesting ratio. As the Lyra siblings requested to be housed together, they were granted their request, along with adding Jane and Élodie to the house. When their housemates were first revealed, Thalita giggled at the thought of Renato being outnumbered by the women, poking fun at her little brother. However, despite the thrown-off ratio, the house is very calm, with the vibes almost always positive. It was easy for the four of them to relax, sharing stories and telling jokes together. Who knew Renato could fit in so well with women…or, maybe it should have been obvious, as his older sister did practically shape his future.

Unlike all the other arrangements before, ‘house 5’ didn’t have any individual requests on housing preferences. This left the overseeing agents to just put a handful of the leftover survivors together. David, Vittorio, Gabriel, and Jeff ended up sharing this house, all on a random chance. Despite the uncertainty at first, the four men realized just how much they had in common. David and Jeff had a particularly fun time showing certain movies and technological pieces to both Vittorio and Gabriel.

One of the men had been too far in the past to really understand everything in the present — despite his previous timeline hopping — while the other had been too far in the future. For Gabriel, it was all about survival and work; there was no time for movies and entertainment — as if everything even survived the downfall — not to mention, this was actually the man’s first time on Earth… Everything was a bit baffling to him at this point.

Similar to the previous residence, the arrangements at ‘house 6’ were also randomly chosen. Ace, Adam, Felix, and Jonah were the only ones not selected now, leaving the agents to group these last few remaining survivors together. Although these four didn’t necessarily seem compatible at first glance, these guys surprisingly clicked together almost instantly. They held a kind of nonchalant vibe to their house, leaving the housemates collectively relaxed. Despite the odds, they get along super well, staying up all night to watch ridiculous, useless documentaries that they just got too invested in.

Moving onto the killer arrangements, they were actually easier to work with. Nearly each victim requested to be with at least one other, making the work much quicker for the agents. At ‘house 7,’ all the Legion decided to crash together, each agreeing to bunk with one another. It wasn’t much different from when they would spend their time at that old, abandoned lodge. However, now they were offered an actual house? Of course their arrangement was a no-brainer.

It was an initial time period shock to the teens who had grown up in the 90's, not having their usual Walkman or CD player. While settling in on their first day, Susie did convince Feng to come over and help the teens navigate their TV, specifically curious about the music. The technology-obsessed girl felt a twinge of pride while opening the group’s eyes to the ‘magnificent wonders’ of…YouTube.

Almost finished with the housing arrangements, the agents had yet another fairly simple pairing as they got to ‘house 8.’ This was the smallest residence, yet it was also only hosting two people: Philip and Max. Per the request of the lanky man, he was paired with Max, who seemed easily lost in screens. Upon realizing how advanced television had become since he was younger, the softhearted man wanted nothing more than to absentmindedly sit in front of a screen all day. Watching the heroic movies he had missed for so long. Philip didn’t mind his housemate’s stranger interests; he was purely here to be by the man’s side, to hopefully help him through some of his medical challenges. Max deserved the compassion and support.

Finally, at the last occupied home was ‘house 9,’ where Anna, Sally, and Carmina all agreed and requested to be together. Sally wanted nothing more than to help Carmina during her time of need, and Anna was just happy to follow behind anything Sally was doing. Both of the women treated their amputee housemate like a daughter, especially Anna, not wasting a single second to push Carmina’s wheelchair or to even carry the girl if it were easier or necessary. It would be a long, rough road for the girl to get her mobility and independence back, yet Anna and Sally were prepared to be with her every step of the way.

—

Giving the victims some space as they settled in, the agents stayed out of the way, conducting their tests from the previous blood draws and DNA samples. As they were looking for any abnormalities — wondering just how deeply this ‘realm’ could have affected them — they also took note of everyone’s secondary genders. Jotting down every answer they obtained in their files, they would soon need to send back the results to the victims. Along with possibly informing some of their identity for the first time, they also needed to set up respective support groups for each secondary gender. It was essentially a more specific form of therapy and would keep peace within the pack if they had an outlet to vent into, especially with double the amount of alphas to omegas in this particular pack.

A scattered — yet organized — mess of papers lay on a desk, each with a victim’s name, their information, and stray papers containing some of their results:

- Group’s pack roles -

• Alphas: Yun-Jin Lee, Yui Kimura, Sable Ward, Jeff Johansen, Anna, and Joey.

• Deltas: Nea Karlsson, David King, Zarina Kassir, Gabriel Soma, Thalita Lyra, Julie Kostenko, and Max Thompson Jr.

• Betas: Meg Thomas, Jake Park, Feng Min, Haddie Kaur, Jane Romero, Élodie Rakoto, Vittorio Toscano, Ace Visconti, Felix Richter, Jonah Vasquez, Philip Ojomo, and Carmina Mora.

• Gammas: Dwight Fairfield, Kate Denson, Renato Lyra, Adam Francis, Frank Morrison, and Sally Smithson.

• Omegas: Claudette Morel, Mikaela Reid, and Susie Lavoie.

#cozyreadingsao3#dead by daylight#dbd#fanfiction#dbd fanfic#dead by daylight fanfic#a/b/o universe#a/b/o fanfic#omegaverse#dbd au#all dbd survivors#heavy megdette focused

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leaving Purity

Leaving Purity https://ift.tt/LpAIKqU by dannihowell For young girls like Hermione, growing up in Purity meant finishing school after the seventh grade, getting married to a Order-approved husband, having babies as soon as possible, and serving the Prophet. The Order of the Pure controlled its members with an iron grip, all in the name of God. When Draco makes a promise he can't possibly keep, Hermione's life changes forever. The events that follow will change the lives of every member of the Order, especially its leader and prophet, Thomas Riddle. Words: 1370, Chapters: 1/13, Language: English Fandoms: Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling Rating: Mature Warnings: Graphic Depictions Of Violence, Rape/Non-Con, Underage Categories: F/M Characters: Hermione Granger, Harry Potter, Draco Malfoy, Narcissa Black Malfoy, Lucius Malfoy, Helen Granger, Robert Granger, Original Child Character(s), Daphne Greengrass, Sirius Black, Remus Lupin, Tom Riddle, Original Characters, James Sirius Potter, Teddy Lupin Relationships: Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy, Hermione Granger/Lucius Malfoy, Harry Potter/Ginny Weasley, Daphne Greengrass/Draco Malfoy, Lucius Malfoy/Narcissa Black Malfoy, Sirius Black/Remus Lupin, Millicent Bulstrode/Daphne Greengrass, Ginny Weasley/OMC, Lucius Malfoy/Original Female Character(s), Hermione Granger's Father/Hermione Granger's Mother Additional Tags: Religious Cults, Alternate Universe, Alternate Universe - Modern Setting, Alternate Universe - Non-Magical, Polygamy, Hermione Granger & Harry Potter are Siblings, Human Trafficking, Organized Crime, Implied/Referenced Child Abuse, Implied/Referenced Homophobia, Implied/Referenced Underage Sex, Forced Marriage, Forced Pregnancy, Implied/Referenced Sexual Assault, Kidnapping, Implied/Referenced Drug Use, Cheating, Alternate Universe - America, Out of Character, Religious Discussion, Implied/Referenced Abuse, Implied/Referenced Character Death, Implied/Referenced Rape/Non-con, Implied/Referenced Domestic Violence, Good Lucius Malfoy, Good Narcissa Black Malfoy, Good Parent Lucius Malfoy, Good Parent Narcissa Black Malfoy, Unspecified Christian Denomination, Slow Burn Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy, Dramione endgame, Poor Ginny, Arranged Marriage, Hermione Granger is Always Right, Hermione is naive, Tom Riddle is a prophet, canon characters used randomly throughout, Fake Adoptions, Control, Death in Childbirth via AO3 works tagged 'Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy' https://ift.tt/x12RdgU March 17, 2024 at 04:07AM

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess of Candy Coated Lies, Modern Royalty AU- King Peter Steele & Single Mother OFC, Soulmate AU

Chapter 1

SUMMARY: Single mother Molly Anne Harper does the best she can do, given her circumstances- since she broke up with her ex-boyfriend by sending him to jail, she’s been struggling to be the best mother to twin daughters while working barely minimum waged jobs. But when she meets her soulmate- King Peter Thomas Ratajczyk of Brooklyn- she quickly finds herself falling heads over heels in love with the guarded, battle damaged ruler. Likewise, Peter finds himself with a family of a women and two little girls who call him daddy. But what happens when their father gets out from behind bars and starts to cause mayhem?

A Soulmate AU where you never know what the first words your soulmate says to you until they say it

STORY WARNINGS: mentions of domestic violence (nothing graphic) mentions of spousal abuse (nothing graphic)

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHORESS: This fic is dedicated to SkullWoogle on AO3 abd @rock-a-noodle on Tumblr.

WORD COUNT: 1534

I tapped my car seat with anxious fingers, unable to stop my nervous twitching as the car paused at the gates before entering the palace grounds, little white and black flags flapping from the front of the high end vehicle.

“You nervous?”

My eyes flitted up to where the noblewoman’s assistant, a mousy young woman with enormous eyeglasses was sitting, her attention on the fat binder that she carried around with her to keep everyone closely on schedule.

“What if he knows that I’m not Lady Bridget?” I tittered, bringing my hands up to my lap so that I could fiddle my thumbs together. “What if he knows at once that I am just a pauper wearing a pretty dress?”

“Molly Anne, can you look at me, please?” I looked up, feeling ashamed that I couldn’t remember her name. I met her soft amber eyes and we both exchanged smiles. “The king is an extremely compassionate and polite man. When you do need to tell him about your plight, I know that he will respond with nothing but the purest kindness.”

“If you say so,” I murmured as the car rolled to a stop, the chauffeur tapping the roof three times before the door to my left was opened. I exchanged glances with the woman, who smiled encouragingly at me as she climbed out first, amazing me with her skillful movement on heels.

I took a shaky breath of air in through my nose and then out again through my mouth as I grabbed my bag and carefully stepped out of the car, squinting at the bright sunlight that almost blinded me when I would move my head in a certain direction.

I took another deep inhale of air as I smiled and nodded at people as I carefully strutted my way into the palace, following Chloe- that was her name. as I walked deeper and deeper into the royal home, I found my mind wandering off to how I became to stand here.

I had earned a top scholarship to Brooklyn’s top university, but had dropped out when I was only a semester away from graduating. I had found what I thought was love, and had stupidly wanted nothing else than to follow him wherever he went.

But he was not a nice man.

He would beat me black and blue while howling in a drunken rage, blaming me for all the world’s problems as he dealt illicit drugs and committed various petty crime for drug money. But when I was arrested for his screw up, I had discovered that I was pregnant, and that was all the encouragement that I needed to shift my life back around again.

Once I had got out from jail in exchange for the laundry list of Henry’s dirty deeds, I had started working honest jobs- one as a waitress at a small diner, the second as a receptionist at a small law firm. I was living in a cramped one bedroomed apartment in the poorer part of the city when I found out that I was carrying twins.

My daughters, Aria and Evie.

My Bluebells and my Bumblebee.

My reasons not to fuck up my life again.

“My lady, would you care to step into here?”

I snapped my eyes out of my daydream state of mine over to where a man in black trousers and a green uniform shirt was motioning me off into a room with double doors worn open.

I nodded my head curtly, snapping into my assigned role of Lady Bridget Barlowe, betrothed to King Peter Thomas Ratajczyk of Brooklyn.

Lady Bridget and I had met entirely by chance, when she had swung into the Copper Penny for a quick bite to eat before heading to her hotel for the night, exhausted from a full day of travel from her home providence to the capitol city. I was covering an extra shift because the Scholastic Book fair was coming up the next week and I wanted to be certain that I would have enough money to let my twins buy three books each, their monthly fun treat.

“Oh my god, we could be twins!” Lady Bridget said to me, removing her sunglasses to grin at me. “What’s your name?”

“My name is Molly Anne, my lady,” I had meeped out timidly.

“Molly Anne, such a pretty name,” she hummed before making me an offer that I could not refuse.

She was to be in Brooklyn for two weeks, entertaining the king as the press would whirl out rumors about a royal wedding, entertaining him however he should ask.

In return, she would deposit five thousand dollars a day into my bank account.

Seventy thousand dollars didn’t sound too bad to sneeze at.

And as a gratuity thank you for my time, she deposited ten thousand dollars into my bank account after I had agreed to do so, me calling both my places of work to put in two weeks of time off, saying that I had doctors’ visits and lab works coming up.

“You are literally the best,” Lady Bridget had told me after I was done making all the necessary phone calls. “Who will look after your daughters? Do you have family? You can bring them here to my hotel room and I’ll keep an eye on them!”

And so that’s what I did- I went and picked the girls up from school before taking them home to pack a few bags.

“Lady Bridget Barlowe!” cried a man into the room before the door were shut, figuratively locking me in with the lion.

The girls had been delighted when I told them that we were going out on an adventure- Aria had tried to pack more books than clothes and her not her toothbrush and Evie began to cry when I told her that she couldn’t bring her water paints with her.

Finally, after about two hours of stopping the girls from sneaking items that they wouldn’t be needing into their bags and checking that the windows were in fact locked, the three of us left the cramped one bedroom, one bathroom apartment that we lived in. I had stopped down at the office down on the first floor to tell the manager that the three of us were leaving to attend to some urgent family business and that I would be unreachable for quite some time.

I took three steps into the library before catching sight of the king- an imposing man at near seven feet in height, he had long dark black waves that he normally kept out of his face in a simple braid, snapping eyes that could make woman faint and moan with desire or make enemies quake in their sleep. His body was lined with hard muscles and heavily masculine tattooed littered his skin- a proud bald eagle on his right shoulder, a snarling panther on his left arm, a green minus sign inside of a zero on his right shoulder, a petitely sized spider on his hip, and more recently, the Greek symbols for Alpha and Omega on his fists.

This man looked like he could smell fear.

And right now, he smelled prime meat.

My heart was thudding in my chest as I quickly gathered myself, getting into character to play the role of a lifetime.

“Kingy,” I sneered, wondering where the hostility between the king and Lady Bridget began and what the story was.

The king’s magnificent head jerked up and his eyes went wide with wonder and something that I thought was love.

The next few words that flew out of him mouth stunned me.

“You’re not Lady Bridget Barlowe, who are you sweetheart?”

TAGLISTS ARE OPEN/ ASK BOX IS OPEN/ REQUESTS ARE OPEN/ PLOT BUNNIES ARE WELCOMED

If you liked this, then please consider buying me a coffee HERE It only costs $3!!!

PETER STEELE TAGLIST

@rock-a-noodle

@xxgreendruidessxx

@ch3rry-c01a

#Type O Negative AU#Modern royalty AU#Royal AU#King Peter Thomas Ratajczyk#FanFiction#Soulmate AU#AU#Molly Anne Harper (OFC)#Chapter 1#Aria Harper (OFC)#Evie Harper (OFC)#Chapter One

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

17 and 22!!

17. Tell us about your favorite character?

Toss up between Yossarian in Joseph Heller's Catch-22 and Oedipa Maas in Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49. They're both paranoid characters, which probably says something about me, but for different reasons. Catch-22 is non-linear so we're introduced to Yossarian as this twitchy hypochondriac who believes everyone wants to kill him. We only learn about why in the novel's final chapter, and it's one of the most horrifying things I've ever read. Catch-22 isn't the first book about how "war is hell," but it's probably the first to be very, very funny too. That's what makes it so chilling when the story becomes very serious.

The Crying of Lot 49 is less intense but it's one of those books that is somehow speaking to the future. Oedipa is a bored housewife who's pulled into a conspiracy when her ex-lover dies and she's named the executor of her estate. The conspiracy involves an ancient postal service that may or may not exist, it's great. It kind of reads like a Q-Anon allegory fifty years before Q-Anon. I love Oedipa because she's not your traditional main character in a paranoid mystery. She lives the ideal modern life, but is still searching for meaning beyond domesticity, and she quickly discovers that the more you search for meaning the less the world has any.

It's probably my favorite book.

22. Something you want to see?

I think Alien: Romulus looks pretty good!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In their book Free to Choose, Rose and Milton Friedman pointed out such patterns more generally: Industrial progress, mechanical improvement, all of the great wonders of the modern era have meant relatively little to the wealthy. The rich in Ancient Greece would have benefited hardly at all from modern plumbing: running servants replaced running water. Television and radio— the patricians of Rome could enjoy the leading musicians and actors in their home, could have the leading artists as domestic retainers. Ready-to-wear clothing, supermarkets— all these and many other modern developments would have added little to their life. They would have welcomed the improvements in transportation and in medicine, but for the rest, the great achievements of Western capitalism have redounded primarily to the benefit of the ordinary person.4

Wealth, Poverty, and Politics by Thomas Sowell

0 notes

Text

Women in modern society can choose one of the two opposite worldviews to establish their values. Traditional women prioritize creating the nuclear family and supporting the patriarchal family structure. Traditional perception is often considered outdated in modern society because it is often associated with religion and supports conservative political views. On the other hand, modern women strive for equal opportunities for both genders and build their careers to be financially independent. There are many differences between traditional and modern women; however, these differences can be linked to two core aspects of women’s life: finances and political views. Discussion Firstly, the financial dependence on a man distinguishes traditional women, who often do not have their sources of income, from modern women who can provide for themselves. In traditional patriarchal families, the husband’s finances are the main source of the family’s income, giving men a dominant advantage (Dewan, 2019). The sole source of income should present the foundation of a family’s financial stability; however, studies show that joint earnings provide a higher level of stability and a higher quality of relationships between spouses (LeBaron et al., 2019). Moreover, financial dependency can expose women to the risks of domestic violence and limit their ability to leave the relationships (Pereira et al., 2020). The topic of women’s financial independence is widely discussed in the media. For example, the Maid series on Netflix shows how men’s willingness to provide for the family can present an attempt to increase control over a partner (Maid, 2021). The women’s need for independent income in films is often portrayed through stories of single mothers (Hustlers, 2021; Herself, 2020). Thus, the media positively portrays modern worldviews to promote women’s financial independence. Furthermore, traditional women often support the interests of men in politics, which leaves them with no opportunities to fight for their rights. One reason modern media rejects traditional women’s values is that these views reinforce conservatism and white nationalism (Gawronski, 2019). Moreover, the traditional anti-feminist views fit all women to the same standard of femininity using negative pressure levers, which rob women of their individuality (Zahay, 2022). Many films capture the negative influence traditional women have on modern women. For example, The Help (2011) captures how traditional wives treated Black maids and supported racist stereotypes enforced by their husbands. The recent film Don’t Worry Darling (2022) suggests that behind the illusion of the ideal life of traditional wives lies a horror in which women are forced to live in a golden cage (Hendy, 2022). Therefore, while modern women actively fight for gender equality, traditional women risk losing their rights because they support men’s views. Lastly, the recent trend of the popularity of traditional femininity aesthetics can also be linked with the negative influence of capitalism and the excessive promotion of feminist values. Thus, it appears that many women consciously reject the values of feminism, justifying it as the manifestation of freedom of choice (Kelsey-Sugg, and Marin, 2021). However, a deeper examination of reasons women switch to traditional values determines that their actions are sourced from the rejection of capitalism (Iovine, 2022). Capitalism prevents women from being housewives because they cannot afford it financially. Furthermore, capitalism forces women to work more because they also have to do household chores after work (Thomas, 2020). Experts connect women’s transition to traditional values with burnout in work/life balance (Froio, 2022). Thus, financial independence presents the main difference between traditional and modern women. Conclusion In conclusion, this essay explored the core differences between traditional and modern women. The essay initially proposed that financial independence and freedom of political views distinguish traditional women from modern. However, after examining the recent trend of the switch to traditional values in women, the essay defined that the desire to be financially independent presents the main difference between modern women. Moreover, the trend shows how economic conditions in the country can force women to shift to traditional values. Reference List Dewan, R. (2019) ‘Gender equalisation through feminist finance’, Economic & Political Weekly, 17, pp. 17-21. Don’t Worry Darling (2022) Directed by Olivia Wilde . Warner Bros. Pictures. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Talk to virtually anyone who grew up in a home with a laundry chute, and chances are they’ll have at least one story about a game they played using the shafts designed to transport dirty clothing, or even a particular mishap where something—or someone—got stuck. But these slide-like tunnels weren’t designed for play: the labor-saving home feature has roots in the domestic science movement (later known as home economics) of the mid-19th through mid-20th centuries, and its quest to make running a household as efficient as possible by applying scientific principles to everyday living. Though once ubiquitous, today, the household features have become relics—easier identifiers of a home’s dated construction, and extremely uncommon in new builds. So, what happened to the trusty laundry chute?One of the first mentions of laundry chutes in the popular press came in an 1891 blurb in the Springfield Republican reprinted in the New York Times, which described "a wilted linen chute" leading to the common laundry room in the basement of a model tenement. It compares the laundry chute to one for mail, cautioning residents against "sending their correspondence to be washed." Around the same time, laundry chutes were likely found in Victorian-era homes of the gentry in England, says Thomas Hubka, an architectural historian and author of How the Working-Class Home Became Modern, 1900–1940. Hubka estimates that laundry chutes made it stateside around 1900, first installed in multistory upper-class houses with servants, then made their way into middle-class homes. "Because laundry chutes were seen in wealthy, elite households, it was appealing to housewives who wanted their home to be the best, most efficient place," he says. "They wanted what rich people had."While the Gilded Age saw wealthy and even middle-class American households employing domestic servants, by the 1910s and ’20s, there was a shift toward having a "servantless home" for all but the richest. This ushered in an era of labor-saving technologies and devices—gas, electricity, vacuums, washing machines—intended to make life easier for the housewives saddled with managing and operating a household. Servants or no servants, most upper- and middle-class homes had a laundry area in the basement, as did some working-class houses. (Working-class households without basements typically did their laundry in the kitchen, Hubka says.) In the days before automatic washing machines were popularized in the late ’30s, doing laundry still involved multiple steps, including hauling all the dirty clothing and linens down to the basement. A laundry chute eliminated that task.By the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, laundry chutes—along with other built-in conveniences—were incorporated into cottages, bungalows, and other compact houses for the middle- and working-classes. Another reason for this, according to James A. Jacobs, architectural historian and author of Detached America: Building Houses in Postwar Suburbia, was that there was a prevailing idea at that time that stairs were treacherous. "Even after World War II, there was a lot of advocacy for one-floor houses, not just because people thought they were modern, but they eliminated dangerous stairs," he explains. As one man who installed a laundry chute in his house put it in a 1947 story in American Home: "I hated to see my wife struggling with armloads of dirty clothes. I shuddered at the thought that she might trip and break her neck tottering down the stairs."Laundry chutes weren’t limited to new builds: in existing homes, they were "so easily built into the walls, between studs," according to a 1931 article in American Builder. Tutorials in home design magazines like House Beautiful walked readers through the installation process, which often involved creating one on the floor of a ground-floor linen closet.Countless laundry chutes were introduced into existing American homes in the 1930s and ’40s thanks to an amendment to the Federal Housing Act of 1934 that introduced a plan through which homeowners could get insured loans of up to $2,000 to make specific upgrades to their homes, including installing built-in laundry and coal chutes, cupboards, broom closets, and garbage receptacles.Send it down the chuteDuring the height of their popularity in the first part of the 20th century, it wasn’t uncommon to have more than one laundry chute in a home. The devices were most commonly placed in hallways near the main bathroom, although they could also be found inside linen closets, bedrooms, bathrooms, and even kitchen cabinets. Either way, the chute emptied into a receptacle in the basement, keeping unsightly dirty clothes out of the living quarters. In the 1920s, some of these hampers were nailed into the joists so they didn’t touch the floor and had small cages built around them, Jacobs says. This kept the laundry off the filthy basement floor, and prevented the person doing the laundry from having to bend down as much.In addition to laundry chutes, some homes built in the first part of the 20th century also had dust chutes—hidden trap doors built into baseboards or the floor itself where you could sweep dirt and dust to make it disappear into a sack in the basement. Similarly, coal chutes were used to transport coal into the basement of a house without having to expose the living space to the filthy fuel. Along the same lines, trash chutes became popular features of apartment buildings (and still are).A linen chute at a Los Angeles hospital in the early 1930sA sanitary and safer solutionLaundry chutes were likely first introduced in hotels, hospitals, and other institutions that housed many people and required a large amount of linens, like bedsheets and towels. The feature was not only convenient, but also thought to be more sanitary, as people believed that unwashed laundry was contaminated with disease-causing germs. In her 1863 book Notes on Hospitals, British nurse, statistician, and social reformer Florence Nightingale recommends that hospitals build "foul-linen shoots" into the wall in order to whisk dirty laundry away from wards as quickly as possible. Although Nightingale called for laundry chutes made of glazed earthenware pipes, the first residential laundry chutes were primarily made of wood, Jacobs explains. But within a few decades, the natural material fell out of favor because splintered wood could snag clothing, and, more importantly, it could help a fire in the basement spread to the upstairs living area, and vice versa.During the "sanitation craze" of the early 20th century, wooden laundry chutes were seen as unsanitary, as the material’s grains and cracks could harbor dirt, dust, and germs. By the 1920s, trade journals typically recommended installing laundry chutes made of aluminum sheeting or glass. Aluminum became the material of choice for laundry chutes, as it was practical, affordable, and, when used with a fireproof door, less prone to spreading fires.A step forward for homemakersDomestic scientist Catharine Beecher recommended laying out a home in a way that would "save many steps"—and therefore cut down on the amount of time needed for housework—as early as 1841. A few decades later, the same concept was used to market laundry chutes to housewives.Home and women’s magazines like House & Garden, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, and the Ladies’ Home Journal ran articles throughout the 1910s and ’20s extolling laundry chutes as a way to cut down on the number of steps women had to take while doing laundry. The feature was even referenced in a 1915 McCall’s article titled "How Suffragists Keep House"—because when you’re fighting for the right to vote, you don’t have time to waste collecting and carrying dirty laundry down to the basement."This is all in line with the American creed of efficiency which gives more leisure as a reward for speedier methods of accomplishing work," reads a 1928 Modern Mechanics article about "the handy dust chute," described as "a counterpart to the laundry chute idea." Building catalogs from the 1910s through the ’50s listed laundry chutes as home features women in particular would find desirable, as they "lessen the burdens of the housewife," one 1922 volume put it.The laundry chute’s last hurrah came in the 1950s, when "homemaking" was still a cultural priority, and postwar suburban homes—like bungalows, ranches with basements, and two-story colonial-style houses—were designed and marketed with housewives in mind, Hubka explains. "It was perfect for the advertisement of the independent woman who is married to a good businessman husband and being an efficient homemaker," he says.But within a decade, society shifted: household efficiency was no longer a top priority, and by the mid-1960s, the popularity of laundry chutes began to wane, Hubka says. The 1970s saw a new trend in residential architecture: cutting costs wherever possible. Houses built in the ’70s weren’t all that different spatially from those constructed in the ’60s, but thanks to inflation, simpler rooms and layouts, and cheaper materials, became increasingly favored, Jacobs explains. "In the 1970s, inflation stamped out every extra you can imagine in a house," he says. "So, if you’re looking to economize, you may not include a laundry chute in your plans."Though the economy eventually bounced back, the popularity of laundry chutes did not. They didn’t disappear completely, but instead of being standard, they were now something homeowners had to request when building a new home—and most people decided that the convenient feature wasn’t worth the additional expense, or the space required to install one. "It’s a reasonable amount of space to give up," Jacobs says. "If you have a laundry chute going through your kitchen and eliminated that, you could create a pantry."The laundry chute’s downfallInterestingly, American houses have only gotten bigger since the laundry chute went out of style. From 1975 to 2023, the average square footage of a new single-family home in the U.S. increased substantially, from 1,660 to 2,514 square feet. While this means there’s now more space to spare—and longer distances to carry laundry—laundry chutes are nowhere near as ubiquitous as they once were. One possible explanation is that larger homes allow for the laundry area to move up in the world, from the basement to a dedicated room or closet upstairs. This has also become more of an option as laundry equipment has gotten cleaner, quieter, and more compact.Still, if a home with two or more stories has a ground-floor laundry room, why not have a chute leading there? Jacobs suspects it may have to do with the fact that we no longer view stairs as a significant threat to our safety. Or it could be the stairs themselves: the widespread adoption of carpeted floors in American homes starting in the ’50s probably made carrying laundry down a plush staircase between a home’s levels feel less daunting than the prior option of navigating open-riser steps to the basement.It may also have to do with the strain of high housing costs, both for living and building. "Laundry chutes are really hard to program sensibly into a [house] plan," Jacobs says. "You have to stack them up in a smart way where it’s in a logical place on each floor—that’s not easy."Or maybe it’s just that priorities have shifted. While middle-class homes from the first half of the 20th century were all about efficiency and built-in conveniences, the 1980s ushered in the era of the McMansion. Many houses built during this period opted for ostentatious amenities—like a pool, two-story foyer, or rec room—over more practical and less-flashy features, like laundry chutes, which are literally hidden with the ductwork. Even following the financial collapse in 2008, when sprawling McMansions gave way to more reasonably sized tract housing—most of these homes with limited floor plan options lacked the convenient features of their mid-20th-century predecessors.Laundry chutes haven’t entirely disappeared from our cultural imagination, but in our homes, even contemporary iterations—like the Laundry Jet, which transports laundry between rooms with a vacuum-powered chute—haven’t taken off. Perhaps we’ve lived without laundry chutes long enough that we’ll forever view them as more nostalgic than necessary.Top photo by Adrian Sherratt/AlamyRelated Reading: Source link

0 notes

Photo

Talk to virtually anyone who grew up in a home with a laundry chute, and chances are they’ll have at least one story about a game they played using the shafts designed to transport dirty clothing, or even a particular mishap where something—or someone—got stuck. But these slide-like tunnels weren’t designed for play: the labor-saving home feature has roots in the domestic science movement (later known as home economics) of the mid-19th through mid-20th centuries, and its quest to make running a household as efficient as possible by applying scientific principles to everyday living. Though once ubiquitous, today, the household features have become relics—easier identifiers of a home’s dated construction, and extremely uncommon in new builds. So, what happened to the trusty laundry chute?One of the first mentions of laundry chutes in the popular press came in an 1891 blurb in the Springfield Republican reprinted in the New York Times, which described "a wilted linen chute" leading to the common laundry room in the basement of a model tenement. It compares the laundry chute to one for mail, cautioning residents against "sending their correspondence to be washed." Around the same time, laundry chutes were likely found in Victorian-era homes of the gentry in England, says Thomas Hubka, an architectural historian and author of How the Working-Class Home Became Modern, 1900–1940. Hubka estimates that laundry chutes made it stateside around 1900, first installed in multistory upper-class houses with servants, then made their way into middle-class homes. "Because laundry chutes were seen in wealthy, elite households, it was appealing to housewives who wanted their home to be the best, most efficient place," he says. "They wanted what rich people had."While the Gilded Age saw wealthy and even middle-class American households employing domestic servants, by the 1910s and ’20s, there was a shift toward having a "servantless home" for all but the richest. This ushered in an era of labor-saving technologies and devices—gas, electricity, vacuums, washing machines—intended to make life easier for the housewives saddled with managing and operating a household. Servants or no servants, most upper- and middle-class homes had a laundry area in the basement, as did some working-class houses. (Working-class households without basements typically did their laundry in the kitchen, Hubka says.) In the days before automatic washing machines were popularized in the late ’30s, doing laundry still involved multiple steps, including hauling all the dirty clothing and linens down to the basement. A laundry chute eliminated that task.By the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, laundry chutes—along with other built-in conveniences—were incorporated into cottages, bungalows, and other compact houses for the middle- and working-classes. Another reason for this, according to James A. Jacobs, architectural historian and author of Detached America: Building Houses in Postwar Suburbia, was that there was a prevailing idea at that time that stairs were treacherous. "Even after World War II, there was a lot of advocacy for one-floor houses, not just because people thought they were modern, but they eliminated dangerous stairs," he explains. As one man who installed a laundry chute in his house put it in a 1947 story in American Home: "I hated to see my wife struggling with armloads of dirty clothes. I shuddered at the thought that she might trip and break her neck tottering down the stairs."Laundry chutes weren’t limited to new builds: in existing homes, they were "so easily built into the walls, between studs," according to a 1931 article in American Builder. Tutorials in home design magazines like House Beautiful walked readers through the installation process, which often involved creating one on the floor of a ground-floor linen closet.Countless laundry chutes were introduced into existing American homes in the 1930s and ’40s thanks to an amendment to the Federal Housing Act of 1934 that introduced a plan through which homeowners could get insured loans of up to $2,000 to make specific upgrades to their homes, including installing built-in laundry and coal chutes, cupboards, broom closets, and garbage receptacles.Send it down the chuteDuring the height of their popularity in the first part of the 20th century, it wasn’t uncommon to have more than one laundry chute in a home. The devices were most commonly placed in hallways near the main bathroom, although they could also be found inside linen closets, bedrooms, bathrooms, and even kitchen cabinets. Either way, the chute emptied into a receptacle in the basement, keeping unsightly dirty clothes out of the living quarters. In the 1920s, some of these hampers were nailed into the joists so they didn’t touch the floor and had small cages built around them, Jacobs says. This kept the laundry off the filthy basement floor, and prevented the person doing the laundry from having to bend down as much.In addition to laundry chutes, some homes built in the first part of the 20th century also had dust chutes—hidden trap doors built into baseboards or the floor itself where you could sweep dirt and dust to make it disappear into a sack in the basement. Similarly, coal chutes were used to transport coal into the basement of a house without having to expose the living space to the filthy fuel. Along the same lines, trash chutes became popular features of apartment buildings (and still are).A linen chute at a Los Angeles hospital in the early 1930sA sanitary and safer solutionLaundry chutes were likely first introduced in hotels, hospitals, and other institutions that housed many people and required a large amount of linens, like bedsheets and towels. The feature was not only convenient, but also thought to be more sanitary, as people believed that unwashed laundry was contaminated with disease-causing germs. In her 1863 book Notes on Hospitals, British nurse, statistician, and social reformer Florence Nightingale recommends that hospitals build "foul-linen shoots" into the wall in order to whisk dirty laundry away from wards as quickly as possible. Although Nightingale called for laundry chutes made of glazed earthenware pipes, the first residential laundry chutes were primarily made of wood, Jacobs explains. But within a few decades, the natural material fell out of favor because splintered wood could snag clothing, and, more importantly, it could help a fire in the basement spread to the upstairs living area, and vice versa.During the "sanitation craze" of the early 20th century, wooden laundry chutes were seen as unsanitary, as the material’s grains and cracks could harbor dirt, dust, and germs. By the 1920s, trade journals typically recommended installing laundry chutes made of aluminum sheeting or glass. Aluminum became the material of choice for laundry chutes, as it was practical, affordable, and, when used with a fireproof door, less prone to spreading fires.A step forward for homemakersDomestic scientist Catharine Beecher recommended laying out a home in a way that would "save many steps"—and therefore cut down on the amount of time needed for housework—as early as 1841. A few decades later, the same concept was used to market laundry chutes to housewives.Home and women’s magazines like House & Garden, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, and the Ladies’ Home Journal ran articles throughout the 1910s and ’20s extolling laundry chutes as a way to cut down on the number of steps women had to take while doing laundry. The feature was even referenced in a 1915 McCall’s article titled "How Suffragists Keep House"—because when you’re fighting for the right to vote, you don’t have time to waste collecting and carrying dirty laundry down to the basement."This is all in line with the American creed of efficiency which gives more leisure as a reward for speedier methods of accomplishing work," reads a 1928 Modern Mechanics article about "the handy dust chute," described as "a counterpart to the laundry chute idea." Building catalogs from the 1910s through the ’50s listed laundry chutes as home features women in particular would find desirable, as they "lessen the burdens of the housewife," one 1922 volume put it.The laundry chute’s last hurrah came in the 1950s, when "homemaking" was still a cultural priority, and postwar suburban homes—like bungalows, ranches with basements, and two-story colonial-style houses—were designed and marketed with housewives in mind, Hubka explains. "It was perfect for the advertisement of the independent woman who is married to a good businessman husband and being an efficient homemaker," he says.But within a decade, society shifted: household efficiency was no longer a top priority, and by the mid-1960s, the popularity of laundry chutes began to wane, Hubka says. The 1970s saw a new trend in residential architecture: cutting costs wherever possible. Houses built in the ’70s weren’t all that different spatially from those constructed in the ’60s, but thanks to inflation, simpler rooms and layouts, and cheaper materials, became increasingly favored, Jacobs explains. "In the 1970s, inflation stamped out every extra you can imagine in a house," he says. "So, if you’re looking to economize, you may not include a laundry chute in your plans."Though the economy eventually bounced back, the popularity of laundry chutes did not. They didn’t disappear completely, but instead of being standard, they were now something homeowners had to request when building a new home—and most people decided that the convenient feature wasn’t worth the additional expense, or the space required to install one. "It’s a reasonable amount of space to give up," Jacobs says. "If you have a laundry chute going through your kitchen and eliminated that, you could create a pantry."The laundry chute’s downfallInterestingly, American houses have only gotten bigger since the laundry chute went out of style. From 1975 to 2023, the average square footage of a new single-family home in the U.S. increased substantially, from 1,660 to 2,514 square feet. While this means there’s now more space to spare—and longer distances to carry laundry—laundry chutes are nowhere near as ubiquitous as they once were. One possible explanation is that larger homes allow for the laundry area to move up in the world, from the basement to a dedicated room or closet upstairs. This has also become more of an option as laundry equipment has gotten cleaner, quieter, and more compact.Still, if a home with two or more stories has a ground-floor laundry room, why not have a chute leading there? Jacobs suspects it may have to do with the fact that we no longer view stairs as a significant threat to our safety. Or it could be the stairs themselves: the widespread adoption of carpeted floors in American homes starting in the ’50s probably made carrying laundry down a plush staircase between a home’s levels feel less daunting than the prior option of navigating open-riser steps to the basement.It may also have to do with the strain of high housing costs, both for living and building. "Laundry chutes are really hard to program sensibly into a [house] plan," Jacobs says. "You have to stack them up in a smart way where it’s in a logical place on each floor—that’s not easy."Or maybe it’s just that priorities have shifted. While middle-class homes from the first half of the 20th century were all about efficiency and built-in conveniences, the 1980s ushered in the era of the McMansion. Many houses built during this period opted for ostentatious amenities—like a pool, two-story foyer, or rec room—over more practical and less-flashy features, like laundry chutes, which are literally hidden with the ductwork. Even following the financial collapse in 2008, when sprawling McMansions gave way to more reasonably sized tract housing—most of these homes with limited floor plan options lacked the convenient features of their mid-20th-century predecessors.Laundry chutes haven’t entirely disappeared from our cultural imagination, but in our homes, even contemporary iterations—like the Laundry Jet, which transports laundry between rooms with a vacuum-powered chute—haven’t taken off. Perhaps we’ve lived without laundry chutes long enough that we’ll forever view them as more nostalgic than necessary.Top photo by Adrian Sherratt/AlamyRelated Reading: Source link

0 notes

Photo