#old art but happy trans day to owen >:]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

(Semi-)OC Profile: Cyrus Vermillion

Another “semi-OC" and one of my main characters in Scarlet Cross!

He’s our favorite plant mage as a trans boy. There is no Mimosa in this universe, and all archives regarding Lady Mimosa Vermillion have been altered by ink magic. There is only Lord Cyrus Vermillion (ʘ‿ʘ✿)

Age: 15 (as of chapter 8) Height: 158cm (hoping for a second growth spurt) Birthday: August 26th Blood Type: O Astrological Sign: Virgo Likes: potion-making, plants and insects, sweets and black tea that would complement them Love Interest: Yuno Grinberryall (ship name “Icarus”)

@artistic-endchamber DREW A BEAUTIFUL RENDITION OF THIS BOY HERE!

But also, behold, some picrew visuals!

Picrew Credit: Left | Right

Additional Details Below the Cut

Cyrus and Yuno’s ship name is Icarus. I decided to go the mythological/aesthetic route because Yuno can fly and Cyrus’ name literally means The Sun. Also, Cyno sounds like a futuristic space pod, and Yunorus sounds like a virus.

Since Mimosa looks like Tetia in canon, Cyrus here looks like a red-headed version of Lumiere. I imagine Tetia and Lumiere to have similar facial structures, given that they’re siblings, and let's face it, most anime faces look similar thanks to the nature of anime art styles. Patry is not happy about this resemblance.

But before his transition, lots of people (including his sister Rose, a.k.a. Girl!Kirsch) said that he looked like his mother, Fleur Vermillion (neé Silva), who looks like a silver-haired version of Tetia. He still takes after his mother, but because of his hair and his clothes, the resemblance is less noticeable to most people. He and Mother have the same smile and the same uncanny way of pestering people with sweet affirmations. Patry’s just in denial.

Plant mages are naturally gifted potion-makers, and Cyrus is no exception. He learned to brew potions from a witch named Edna at the Black Market (recommended by Owen, who also had his fair share of dealings there). At first, Cyrus was only there to learn how to brew the phloxglove potion—a puberty-blocking potion for his transition (and a pun because “foxglove” + “night phlox”, with night phlox being a key ingredient in this potion). Then, he realized that potions have wide applications to supplement recovery magic, so he decided to learn everything he could.

Whenever Cyrus was in the Black Market, his codename was Ambrose (inspired by Ambrosia). He also stumbled upon an injured Zora (whom he calls “Mask”) who won a dueling match at the Black Market amphitheater. He could only do first aid and heal non-fatal wounds since he didn’t have a grimoire yet, but still, he accidentally became a vigilante because he couldn’t leave an injured person alone, no matter how rude they were. And when he learned that Zora wasn’t the only reckless fighter here, he kept coming back to make sure no one would die from their stupidity.

As a consequence, “Mask” ended up meeting “Ambrose” every week for two years. He also bullies Zora into teaching him some basic runes, which means that when he goes to Heart to study at 13 years old, he asks to learn Mana Method instead of (per my headcanon of Mimosa’s first time in Heart) focusing on natural wonders like plants native to the kingdom. That means Cyrus can already use rune arrays by the time of the main plot.

Cyrus never gets a crush on Talia, unlike his canon counterpart’s crush on Asta. There is no love triangle in Ba Sing Se in Scarlet Cross. The “divergence” here is caused by the fact that Cyrus first officially meets Talia while she’s with Leopold, so Cyrus’ first impression of Talia is “aww look, it’s Leo and a Smaller, Louder Leo, that’s delightful”. The association of Talia with his cousin ruined any semblance of romantic inclinations Cyrus might’ve otherwise had.

Fuegoleon gives Cyrus a congratulatory gift on the day he moves into the Golden Dawn base: Calvin the Venus Flytrap. Calvin is a good, enchanted plant boy. Calvin is Cyrus’ beloved minion. Calvin will devour the limb of his master’s enemy and be proud of it. (I’ll add a hyperlink to Calvin’s profile here once it’s ready.) @artistic-endchamber also has an enchanted plant counterpart for Mimosa in their universe, Celia the Venus Flytrap. If Celia and Calvin ever meet, they will mate, and the world may not survive.

With Cyrus’ name and orange hair, it is only natural that @artistic-endchamber’s OC Mai calls him “Big Brother Citrus”. His eyes are also golden, which is pretty darn close to the shade of lemons, so that’s a double citrus attack.

Yami calls Cyrus “Treehugger”, and Edna (the potions master) calls him “Greenie”. Zora calls him “Pipsqueak” instead of Ambrose to spite him. And his mother, Fleur, calls him Sunshine. Fleur belongs to @f-oighear and she's the best.

Before Cyrus came out as trans, his nickname used to be “Sunflower”, to go with his deadname “Mimosa”, a flower that can sometimes be sunshine yellow. But he told his mother that he didn’t want to be a flower anymore, because he associated flowers with girls at the time (considering Fleur and Rose’s names). That’s why Fleur changed his nickname to Sunshine.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: As a beginner in Classics I love your Classicist themed posts. I find your caption perfect posts a lot to think upon. I suppose it’s been more than a few years since you read Classics at Cambridge but my question is do you still bother to read any Classic texts and if so what are you currently reading?

I don’t know whether to be flattered or get depressed by your (sincere) remarks. Thank you so much for reminding me how old I must come across as my youngish Millennial bones are already starting to creak from all my sins of past sport injuries and physical exertions. I’m reminded of what J.R.R Tolkien wrote, “I feel thin, sort of stretched, like butter scraped over too much bread.” I know the feeling (sigh).

But pay heed, dear follower, to what Menander said of old age, Τίμα το γήρας, ου γαρ έρχεται μόνον (respect old age, for it does not come alone). Presumably he means we all carry baggage. One hopes that will be wisdom which is often in the form of experience, suffering, and regret. So I’m not ready to trade in my high heels and hiking boots for a walking stick and granny glasses just yet.

To answer your question, yes, I still to read Classical literature and poetry in their original text alongside trustworthy translations. Every day in fact.

I learned Latin when I was around 8 or 9 years old and Greek came later - my father and grandfather are Classicists - and so it would be hard to shake it off even if I tried.

So why ‘bother’ to read Classics? There are several reasons. First, the Classics are the Swiss Army knife to unpick my understanding other European languages that I grew up with learning. Second, it increases my cultural literacy out of which you can form informed aesthetic judgements about any art form from art, music, and literature. Third, Classical history is our shared history which is so important to fathom one’s roots and traditions. Fourth, spending time with the Classics - poetry, myth, literature, history - inspires moral insight and virtue. Fifth, grappling with classical literature informs the mind by developing intellectual discipline, reason, and logic.

And finally, and perhaps one I find especially important, is that engaging with Classical literature, poetry, or history, is incredibly humbling; for the classical world first codified the great virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, loyalty, sacrifice, and courage. These are qualities that we all painfully fall short of in our every day lives and yet we still aspire to such heights.

I’m quite eclectic in my reading. I don’t really have a method other than what my mood happens to be. I have my trusty battered note book and pen and I sit my arse down to translate passages wherever I can carve out a place to think. It’s my answer to staving off premature dementia when I really get old because quite frankly I’m useless at Soduku. We spend so much time staring at screens and passively texting that we don’t allow ourselves to slow down and think that physically writing gives you that luxury of slow motion time and space. In writing things out you are taking the time to reflect on thoughts behind the written word.

I do make a point of reading Homer’s The Odyssey every year because it’s just one of my favourite stories of all time. Herodotus and Thucydides were authors I used to read almost every day when I was in the military and especially when I went out to war in Afghanistan. Not so much these days. Of the Greek poets, I still read Euripides for weighty stuff and Aristophanes for toilet humour. Aeschylus, Archilochus and Alcman, Sappho, Hesiod, and Mimnermus, Anacreon, Simonides, and others I read sporadically.

I read more Latin than Greek if I am honest. From Seneca, Caesar, Cicero, Sallust, Tacitus, Livy, Apuleius, Virgil, Ovid, the younger Pliny to Augustine (yes, that Saint Augustine of Hippo). Again, there is no method. I pull out a copy from my book shelves and put it in my tote bag when I know I’m going on a plane trip for work reasons.

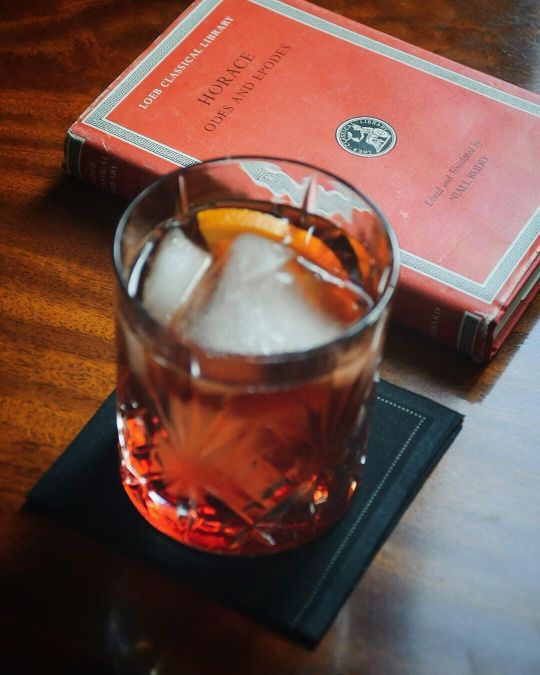

At the moment I am spending time with Horace. More precisely, his famous odes.

Of all the Greek and Latin poets, I feel spiritually comfortable with Horace. He praises a simple life of moderation in a much gentler tone than other Roman writers. Although Horace’s odes were written in imitation of Greek writers like Sappho, I like his take on friendship, love, alcohol, Roman politics and poetry itself. With the arguable exception of Virgil, there is no more celebrated Roman poet than Horace. His Odes set a fashion among English speakers that come to bear on poets to this day. His Ars Poetica, a rumination on the art of poetry in the form of a letter, is one of the seminal works of literary criticism. Ben Jonson, Pope, Auden, and Frost are but a few of the major poets of the English language who owe a debt to the Roman.

We owe to Horace the phrases, “carpe diem” or “seize the day” and the “golden mean” for his beloved moderation. Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, of Ancient Mariner fame, praised the odes in verse and Wilfred Owen’s great World War I poem, Dulce et Decorum est, is a response to Horace’s oft-quoted belief that it is “sweet and fitting” to die for one’s country.

Unlike many poets, Horace lived a full life. And not always a happy one. Horace was born in Venusia, a small town in southern Italy, to a formerly enslaved mother. He was fortunate to have been the recipient of intense parental direction. His father spent a comparable fortune on his education, sending him to Rome to study. He later studied in Athens amidst the Stoics and Epicurean philosophers, immersing himself in Greek poetry. While led a life of scholarly idyll in Athens, a revolution came to Rome. Julius Caesar was murdered, and Horace fatefully lined up behind Brutus in the conflicts that would ensue. His learning enabled him to become a commander during the Battle of Philippi, but Horace saw his forces routed by those of Octavian and Mark Antony, another stop on the former’s road to becoming Emperor Augustus.

When he returned to Italy, Horace found that his family’s estate had been expropriated by Rome, and Horace was, according to his writings, left destitute. In 39 B.C., after Augustus granted amnesty, Horace became a secretary in the Roman treasury by buying the position of questor's scribe. In 38, Horace met and became the client of the artists' patron Maecenas, a close lieutenant to Augustus, who provided Horace with a villa in the Sabine Hills. From there he began to write his satires. Horace became the major lyric Latin poet of the era of the Augustus age. He is famed for his Odes as well as his caustic satires, and his book on writing, the Ars Poetica. His life and career were owed to Augustus, who was close to his patron, Maecenas. From this lofty, if tenuous, position, Horace became the voice of the new Roman Empire. When Horace died at age 59, he left his estate to Augustus and was buried near the tomb of his patron Maecenas.

Horace’s simple diction and exquisite arrangement give the odes an inevitable quality; the expression makes familiar thoughts new. While the language of the odes may be simple, their structure is complex. The odes can be seen as rhetorical arguments with a kind of logic that leads the reader to sometimes unexpected places. His odes speak of a love of the countryside that dedicates a farmer to his ancestral lands; exposes the ambition that drives one man to Olympic glory, another to political acclaim, and a third to wealth; the greed that compels the merchant to brave dangerous seas again and again rather than live modestly but safely; and even the tensions between the sexes that are at the root of the odes about relationships with women.

What I like then about Horace is his sense of moderation and he shows the gap between what we think we want and what we actually need. Horace has a preference for the small and simple over the grandiose. He’s all for independence and self-reliance.

If there is one thing I would nit pick Horace upon is his flippancy to the value of the religious and spiritual. The gods are often on his lips, but, in defiance of much contemporary feeling, he absolutely denied an afterlife - which as a Christian I would disagree with. So inevitably “gather ye rosebuds while ye may” is an ever recurrent theme, though Horace insists on a Golden Mean of moderation - deploring excess and always refusing, deprecating, dissuading.

All in all he champions the quiet life, a prayer I think many men and women pray to the gods to grant them when they are caught in the open Aegean, and a dark cloud has blotted out the moon, and the sailors no longer have the bright stars to guide them. A quiet life is the prayer of Thrace when madness leads to war. A quiet life is the prayer of the Medes when fighting with painted quivers: a commodity, Grosphus, that cannot be bought by jewels or purple or gold? For no riches, no consul’s lictor, can move on the disorders of an unhappy mind and the anxieties that flutter around coffered ceilings.

Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt (they change their sky, not their soul, who rush across the sea.)

Part of Horace’s persona - lack of political ambition, satisfaction with his life, gratitude for his land, and pride in his craft and the recognition it wins him - is an expression of an intricate web of awareness of place. Reading Horace will centre you and get you to focus on what is most important in life. In Horace’s discussion of what people in his society value, and where they place their energy and time, we can find something familiar. Horace brings his reader to the question - what do we value?

Much like many of our own societies, Rome was bustling with trade and commerce, ambition, and an area of vast, diverse civilisation. People there faced similar decisions as we do today, in what we pursue and why. As many of us debate our place and purpose in our world, our poet reassures us all. We have been coursing through Mondays for thousands of years. Horace beckons us: take a brief moment from the day’s busy hours. Stretch a little, close your eyes while facing the warm sun, and hear the birds and the quiet stream. The mind that is happy for the present should refuse to worry about what is further ahead; it should dilute bitter things with a mild smile.

I would encourage anyone to read these treasures in translations. For you though, as a budding Classicist, read the texts in Latin and Greek if you can. Wrestle with the word. The struggle is its own reward. Whether one reads from the original or from a worthy translation, the moral virtue (one hopes) is wisdom and enlightenment.

Pulvis et umbra sumus

(We are but dust and shadow.)

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#classical#greek#latin#horace#poetry#literature#arts#cambridge#classics#personal#study#habits#reading#books#culture#personal growth

71 notes

·

View notes