#possession trope. resurrection trope. in one. character. wow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ghosts of the Shadow Market Commentary pt. 9

The Lost World:

- I haven’t heard anything from this story as well! I think it’s about Ty and Libby’s ghost! That’s all I know

- Ty is the smartest most stupid character we’ll ever meet. His shitty plan will blow up in his face and we will be the ones picking up the pieces. Just wait

- I’m glad Jia is feeling better. Although I think she’s one of the characters that will bite the dust in twp but good thing she’s fine by now

- Livvy and ty need to get their shit together or I’ll call the ghostbusters

- Idk if I said this in my TDA commentary, but I think Scholomance is one of the stupidest names one could come up with

- I like how Livvy is grateful for being a ghost, coming back to life and stuff. It’s kinda new when it comes to this trope. We always get the ghost wanting peace, to move on, etc. it feels exciting plot wise

- In the words of trin Lovell: lesbian rights!

- We literally had a “save the cat” moment, huh

- Stop trying to make LA look dreamy! I went there! LA fucking sucks!

- Zara. My favorite character is back. (This is sarcasm if you can’t tell)

- Villains who believe they’re doing the right thing will always be more interesting than just plain evil

- I need more Helen and Aline!

- I love Paranormal Activity!

- Oh! I just noticed! We haven’t gotten Jem’s pov in this story yet! I wonder if he’ll show up with Tessa giving birth and stuff

- Kit! I missed my chaotic son!

- Does Livvy want to possess a baby? I mean, I know she’s desperate and wants to live but damn! That’s dark!

- Of course they’ll name their daughter after Will!

- Magnus ex machina always there to save the day

- I agree with Livvy here. Why do boys have to be so stupid? Just say you love each other

- Catarina is the most underrated character in this entire series. In this essay I will...

- As someone with 6 names, it’s safe to say Mina’s name could be longer

- I’m thankful we got some clarification on how the resurrection worked cause I was still confused

- Anush is precious! I hope Ty becomes his friend

- Siblings being cute! I love it

- Yeah! Write to kit! Do it! Do it!

- Wow! This was easily one of my favorites! I really enjoyed it!

#lety rambles#tsc#tmi#tda#book commentary#twp#livvy blackthorn#ty blackthorn#kit herondale#jem carstairs#tessa gray#magnus bane#qoaad spoiler#queen of air and darkness#gotsm#gotsm spoilers

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get to know me: MDZS Edition

Get the template by @zhuilingyizhen here

// General //

If you had to join a sect, which would you join? GusuLan Sect. I know, there’s so many rules, but I can’t deal with lively, loud or hot places, so Lan it is.

Your three favorite characters? Wei Wuxian, Lan Wangji, Lan Shizui

Manhua, donghua, novel, live-action, or audio drama? Probably live action. I absolutely love and adore the novel because it gave us married and domestic WangXian (and of course ALL the delicious dirty SMUT), but there’s just something about the live action that captured my heart. Wang Yibo and Xiao Zhan just breathed so much life into the characters. The donghua is cute, the manhua is even cuter and the audio drama is absolutely lovely, but they’re mostly an added bonus.

List your favorite sects, in order. Dang, that’s hard. Depends on what characteristics I’m going by. Going just by aesthetics it would probably be YunmengJiang, GusuLan, LanlingJin, QingheNie, QishanWen.

How long have you been in the fandom? Not long, February probably, but my obsession hit really hard. It’s the first time I’ve been active in a different fandom than HP since 2005 (can you imagine?).

// Ships //

What’s your OTP? WangXian, no question about it.

What’s your NOTP? Or any other ship you hate? Any with Wei Wuxian or Lan Wangji not with each other, I’m possessive.

Other ships you like? I’m not particular about other ships, there are a lot of cute ones.

Thoughts on Wangxian? 🤔 The best thing to happen since... anything basically. I wish novel!WangXian would use lube though, please. Do it for Bichen.

Platonic OTPs/BROTPs? Rarepairs? OT3+s? No particular preference.

Describe a ship in five words. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

// Characters //

If you could date any character from MDZS, who would you pick? Wow, that’s difficult to answer. Definitely neither WWX or LWJ because they belong with each other. In a perfect world, it’d be someone who’d treat me right, like Lan Xichen (I’m too old for Lan Shizui, so he’s out)... but realistically it’d probably be someone like Jiang Cheng or Nie Mingjue because I’m weak for dominant, moody, grumpy men with soft cores. Also, apart from fanficition I don’t enjoy romantic/couply things in RL, so it’d fit I guess.

If you had to kill a character, who would you kill? Xue Yang, Wen Ruohan, Wen Chao or Su She probably. I’m on the fence with Meng Yao because without him WWX probably wouldn’t have been resurrected, so I don’t know.

Favorite character & why? Lan Wangji. I just find him really interesting and unusual.

Least favorite character & why? Probably Meng Yao. The other “evil” characters didn’t try to hide they’re evil whereas Meng Yao pretended to be innocent right until the end and betrayed those that loved him just to reach some idiotic goal. I hate snakes like him.

Favorite character of the juniors? [don’t forget OYZZ] Lan Jingyi probably, because he’s pure comic relief.

Favorite character from each main sect (secondary is optional)? I’m excluding WWX and LWJ here, just because) Jiang Yanli, Lan Xichen, Jin Ling, Nie Huaisang, Wen Yuan (Wen Ning following closely behind, literally).

// Story //

If you could make one major story change, what change would you make? Why? This is too hard to answer. I’ve read so many fix-it-fics and no matter what is changed, there’s always something I miss from the original work. If I’d kill Wen Ruohan beforehand, I’ll miss WWX’s interaction with the Wen survivors etc. I think it would bring less pain all around if neither WWX nor JC ever lost their cores but who knows how that would’ve changed things. Maybe it also would’ve helped if WWX realized LWJ’s feelings earlier, but we’ll never know.

Which character would you bring back to life? Jiang Yanli, definitely. There’d be a lot less hurt between JC and WWX and the siblings would be reunited again.

You can bring one character back to life, but you must pick someone else to die in their place. Would you do it? How would this affect the story? If I brought back Jiang Yanli in exchange for one of my hated characters (i.e. Xue Yang, Meng Yao or Su She), that’d work out for everyone probably?

// Fic //

Do you write fic for MDZS? If so, what’s your ao3/wattpad/ff.net? Nope, I’ve only drawn so far, if you wanna see, check out my art tumblr.

What characters/ships do you mostly write/draw for? Only WangXian!

Favorite tropes & which characters? Lovely dovey & domestic fluff. Scenes from the book as well.

AUs or canon-verse? Argh, again with the difficult questions. I love modern!WangXian but I also love post-canon!WangXian a lot.

Recommend a fanfic!! Can be yours or someone else���s. I have too many favourite fics! Here, have some I’ve read recently and absolutey adored: “the kite string and the anchor rope” by fleurdeliser (features WWX and LWJ raising LSZ together in Cloud Recesses, 39k) “like wildflowers (we grow)” by moonsteps (features Wei Ying as Lan Zhan's son's teacher, Lan Zhan is also a teacher at the same school, 80k) “A Little Happiness” by Suspicious_Popsicle (features de-aged Lan Wangji, 20k) “Night of Sixth Magnitude Stars” by Leffy (features LWJ as WWX’s teaching assistant, saying more would be spoilery, 22k)

@ a friend, answer them yourself, or send an ask w/ category & number!!

#i was in the mood to do this#feel free to do it as well#or just use the template for your followers to ask you#mdzs#mdzs meme#cql#the untamed#mo dao zu shi#grandmaster of demonic cultivation

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re-Fridging Mary Winchester? The Ouroboros Narrative Swallows its Origin Story (14x18)

This is the last time we see Mary Winchester alive (14x17 Game Night). Her last words are, “Jack, please, listen to me!” and her last shot is this shaky close-up, straight to camera.

(Image credit Wayward Winchester https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BIbBibdvsaM )

Doesn’t it look as if she’s directly addressing the audience here, as if to say, “Hey, folks, pay close attention!”?

The “real” Mary is, like the title of the episode (Absence) absent in 14x18.

Rowena says, after doing her locator spell, that Mary, “...is not on this earth.” We see ash that is supposedly hers, as Jack tries desperately to “resurrect” her. We learn Castiel has seen her soul in Heaven, but we do not see her, only the apparent door to her Heaven:

And the “body” Jack raises using Rowena’s necromancy spell? It is not Mary:

(Image credit Wayward Winchester: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ny7tLZC3nto )

Sam is very explicit about that. He says, “I talked to Rowena. She said she thinks that what Jack brought back, he just brought back a shell, a body, y’know, that it was empty, just a... replica, incapable of holding life.”

A replica, like... a doppleganger, a mirror-image?

The shot above, of her sons holding this shell, this replica-double, is laid out at a boundary, between grass and ash, between life and death, almost as if between one world and another (separated, perhaps, by a portal?).

You might have seen my posts already about 14x17 Game Night and 14x18 Absence, wherein I am suspicious (for various reasons) as to whether that is really the last we will see of Mary Winchester on the show. Just as I am suspicious about Jack’s “Hallucifer” really just being a part of his own mind, because likewise, I highly doubt we have seen the last of Lucifer on the show:

http://drsilverfish.tumblr.com/post/183968888069/lucifer-rides-again-games-within-games

http://drsilverfish.tumblr.com/post/184140015899/14x18-absence-the-games-continue

So, my consideration of the re-fridging of Mary Winchester in the S14 SPN narrative is caveated by the fact that I have a sense that this re-fridging may be contingent rather than final.

It is also caveated by the fact that Mary’s second (apparent) fridging was handled by Berens in a way which subverts it, because, as outlined above, Mary herself is absent from the mise-en-scène of her re-fridging. She has noped out of it!

But, if my suspicions concerning another twist to this narrative are incorrect (and I hope they’re not) then, deft or not, Mary is still dead again to further our male protagonists’ narratives.

I think we’re probably all familiar with the term, “fridging”....

The term originates with Gail Simone, a comic book writer who created the website Women in Refrigerators in 1999 (twenty years ago now, wow).

This is the link to the website (still live) and this is an excerpt of what she said:

“This is a list I made when it occurred to me that it's not that healthy to be a female character in comics. I'm curious to find out if this list seems somewhat disproportionate, and if so, what it means, really.

These are superheroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator. I know I missed a bunch. Some have been revived, even improved -- although the question remains as to why they were thrown in the wood chipper in the first place.”

http://lby3.com/wir/

The trope, “fridging”, has now taken on an established life of its own in pop-culture criticism.

Here is some more discussion of it in an article by Maria Norris “ Comics and Human Rights: A Change is Gonna Come. Women in the Superhero Genre” (2015).

“The trope Simone describes is now widely acknowledged, and the practice it describes has come to commonly known as ‘fridging’. The superhero genre typically depicts interactions and relationships between male and female characters that lack consequence, emotional resonance, permanence and accountability. Often, these fictional relationships stagnate, or end tragically. Too often, women in superhero comics become pawns in schemes meant to develop male characters or give them motivation to act.”

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/80285/1/Comics%20and%20Human%20Rights_%20A%20Change%20is%20Gonna%20Come.pdf

So, we can define fridging, from these sources as - the often gruesome or shocking death of a female character, for the primary purpose of driving male character motivation or development.

Whilst the trope may have been defined in the 1990s, it is much older in literature. We could argue that Oedipus’ mother, Jocasta, was fridged, for instance, because who she is (Oedipus’ birth mother) and her suicide, are framed as being all about Oedipus and the impact on Oedipus. We could even argue that Shakespeare fridged Ophelia, whose tragic suicide is driven by Hamlet’s cruelty (and his murder of her father) and whose death, in the play, is primarily designed to impact her menfolk - Hamlet (her beloved) and her brother Laertes.

Essentially, what we mean by the “fridging” of a female character is that in stories (usually by men) where men are the protagonists and the heroes (or tragic heroes or anti-heroes) sometimes (by no means always) women are written as primarily existing in relation to those men, so that their own deaths are not about themselves, but are used principally to explore the emotional landscapes of the hero-protagonists to whom they mattered and who live on after they are gone.

Mary Winchester’s original fridging, her gruesome burning on the ceiling, which we the audience see in 1x01 Pilot, provides the origin story for Supernatural.

Mary is fridged because she is dead the moment we meet her.

We don’t have time to get to know who she is, or what her death means as part of her own journey. She is killed gruesomely and that death provides major character motivation and development for her husband John Winchester and for her sons Sam and Dean. She is, originally, defined primarily by her relationships to them; as a dead wife and a dead mother.

Mary Winchester is fridged by fire and her menfolk are thus “birthed” into narrative. Over her silenced and torched corpse, they become words and action. Their narrative journey begins because hers ends.

That fridging is, in the very same pilot episode, repeated for Sam’s girlfriend Jess:

Supernatural, it is thus swiftly established (by a double fridging at the outset) is, overtly, a story of heterosexual men (John and Sam being so established by their relationships to Mary and Jess) without familial women. Men who have been initiated into a world of violence and grief, powerfully driven by revenge, because their women-folk have been slaughtered.

(Dean, however, has been queer-coded from the beginning, but that’s another story.)

In the established patriarchal order of the SPN universe (in which stories about men are central and stories about women are peripheral) heightened masculine emotion (which lies at the heart of Supernatural) is thus created and legitimised, by the death of women.

When Bobby becomes the Winchesters gruff substitute father-figure (with a gooey, although masked, heart-of-gold centre) his own back-story repeats the pattern. We learn Bobby had to kill his own wife, Karen, whilst she was possessed by a demon (see 3x10 Dream a Little Dream of Me, 5x15 Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, and 7x10 Death’s Door). In Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Karen is raised as a zombie by Death, and Bobby is forced to kill her all over again, thus, once more, reinforcing the death of familial women as the origin point for the centrality of masculine emotion in the narrative. Karen, in the SPN narrative, does not really exist as her own person, only as Bobby’s tragic wife, framed, rather tellingly, as a home-maker and help-meet in this shot from 5x15:

Familial women, associated with the core male characters in Supernatural are thus, initially, strongly framed as occupying the domestic space, the hearth-fire, whilst hunting and the open road belongs to their (bereaved) menfolk.

For Mary Winchester, however, things become a little more complicated than that. Because, thanks to the time-travel abilities of the angels, she is “resurrected” in 4x03 In the Beginning and 5x13 The Song Remains the Same and her sons get to meet a living, younger, version of her. Mary becomes a person, raised as a hunter in her own right, rebellious, brave, independent, determined, a fighter. We see her having something of her own agency, although to a limited extent, in that she remains “trapped” by the angel breeding programme and the fate the angels have laid out for her - to marry John and to bear angel-vessel sons. She cannot therefore, escape her primary framing as a wife and mother, as in this shot from 5x13:

So, when Dabb inaugurated his era as showrunner, and his Ouroboros narrative structure, by taking us back to the start of Superantural and re-working the story by unnfridging Mary Winchester (11x23 Alpha and Omega):

(Image credit: http://timetraveldean.tumblr.com/post/144939142393 )

it was such a brilliant “un-zipping” of the original SPN narrative architecture. The Ur “woman in white” was back from the dead; Supernatural was going meta-narrative on its own ass in a big way. By having Mary brought back to life from Heaven by the feminine God-principle in the universe, Amara, who had previously been unjustly locked away by her brother, God, SPN was critiquing its own patriarchal origin story.

Yay!

Which is why Mary’s re-fridging in 14x18, IF the writers’ room is playing it straight (and, as above, I have my strong doubts about that) would be so disappointing.

Sure, on one level, from Dabb’s Ouroboros narrative perspective, it makes impactful and symmetrical sense.

Jack was always paralleled to Azazel, as well as to Dean and Sam, at his birth - see this meta of mine on 12x23 All Along the Watchtower:

http://drsilverfish.tumblr.com/post/160876601179/all-along-the-watchtower-12x23-and-12x22-and

A yellow-eyed supernatural being in a nursery, a baby, and a mother who dies. The ingredients are the same (1x01 and 12x23) - the recombination is different, as part of the narrative journey.

Mary’s first death inaugurated Dean as substitute-parent to Sam.

Jack’s mother, Kelly Kline’s death, inaugurated the Winchesters as substitute parents to Jack. And oh boy, did the narrative not treat Kelly Kline well. Kelly Kline was stealth-raped by Lucifer and died giving birth to Jack (her body mystically ripped apart by the birth). Kelly was fridged for Jack’s nascent emotional journey, because, once again, the show’s core depends on the absence of familial women.

Kelly Kline dies giving birth to Jack (12x23)

Jack’s birth and Sam and Dean’s parental responsibility for him also coincided with Castiel’s death, thus (in subtext) the narrative also mirrored Dean’s grief at losing Cas to his father John Winchester’s grief at losing Mary.

In a patriarchal culture where male feeling is repressed, which is definitely the in-show world of Supernatural (mirroring aspects of IRL US culture) the stakes, apparently, “have to” be bloody, they “have to” be high, in order for the narrative to “permit” the levels of traumatic emotion which Dean and Sam (and now Jack) continually cycle through, whilst maintaining their ostensibly “tough” hunter hero status.

The bedrock of that “permission”, i.e. permission to be a show about male sentiment? With Kelly Kline’s death, it continued to be predicated on the violent death of familial women - at the very moment the Winchesters themselves became fathers.

Dabb used the same (tired) trope in 9x20 Bloodlines (Ennis lost his girfriend to a werewolf attack, and was thus deeply emotionally wounded and bent on revenge).

Female familial death is the narrative “excuse” for the homo-social world of SPN, and it also works to contain the homoerotic subtext of SPN. Women are ostensibly, only absent from these men’s lives because they keep traumatically losing them, not because they, in fact, prefer the company of other men.

Two grown brothers and a male-embodied angel who live together, have adopted a son together, and who spend all their time in states of incredible emotional angst?

Hollywood culture (and the mainstream audience it imagines it is speaking to) still (for the most part - although let’s acknowledge Tapert’s Spartacus for Starz, 2010-2013) cannot compute how to experience that kind of set-up as both “queer” AND “manly” (which is why Troy [2004] eviscerates the homo-romantic from Achilles/ Patroclus) so the violent death of familial women in Supernatural is used as an excuse for their absence

Mary’s ostensible death in 14x18 seems, once again, to re-affirm this patriarchal order, even though, in her time back on earth, from 11x23 to now, Mary has been written and portrayed as a flawed, real person; her apple-pie baking, perfect Mom, childhood mirage (Dean’s dream of her idealised memory) thoroughly deconstructed. And I have lived for that.

To have her re-fridged, for her sons’ man-pain (i.e. for the narrative “permission” to cycle through grief and angst and growth again) after all that, just sits wrong with me.

And, despite the beauty of Beren’s structure, despite his respectful treatment of her, make no mistake, Mary is (if we read this as played straight) re-fridged, because her death, is not about her or her own journey, rather, narratively, it now deliberately leaves her sons in the place of their father.

A yellow-eyed “demon” (their adopted Nephilim son Jack, whom they fear has lost his soul) has killed Mary Winchester, again. Will the Winchesters follow in the footsteps of John Winchester’s revenge quest, or will they find another way?

I really hope Mary comes back from the AU world she’s been un-wittingly blasted to by Jack to kick some sense into her sons’ asses and, oh yeah, punch Lucifer in the face all over again:

Mary punching Lucifer in 13x22 Exodus.

#Supernatural#14x18#Absence#spn meta#Meta#Re-fridging Mary Winchester#Ouroboros narrative#Dabb era spiral narrative#Jack the Nephilim#Azazel#Narrative mirrors#Winchester Family Dynamics#14x17#Game Night#1x01#Pilot#3x10#Dream a Little Dream of Me#5x15#Dean Men Don't Wear Plaid#7x10#Death's Door#4x03#In the Beginning#5x13#The Song Remains the Same#11x23#Alpha and Omega#12x23#All Along the Watchtower

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seasonally Appropriate, part I: A Long Look at Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

So it's Halloween season, and I thought maybe it would be interesting/entertaining for me to tackle some themed content. So here we go.

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

There are few video game series that so clearly fit the season as Castlevania. A series that usually has Dracula as its final boss, with any number of mummies, werewolves, and Frankenstein's monsters prior to the ultimate showdown with Bram Stoker's Wallachian sensation, there are few that are perhaps a better fit for the season. And this is just a small sample of the horror and horror-adjacent enemies (we've also got your standard zombies, ambulatory skeletons of varying sizes, gargoyles, giant bats, and giant spiders, gorgon heads, Medusa herself, and even the grim reaper).

But despite the parade of classic horror monsters, Castlevania has never really been scary. It's really always been more of a sort of horror fantasy than anything.

Most installments prior to Symphony of the Night featured you playing as a muscular hero who is the latest scion of the Belmont clan, a powerful, nearly barbarian folk whose sole heirloom appears to be an enchanted chain whip (with a spiked morning star on the end) which is consecrated for killing vampires and other creatures of the night. It's a good thing they have it, because Dracula, in life an evil sorcerer, and in death the king of vampires, seems to come back to life every century. Sometimes this happens on its own, sometimes he's resurrected by various disciples.

Listen, the lore here is neither deep, complex, nor consistent. Anyway, Symphony of the Night marked an interesting fork in the series development.

Let's look back for a minute at the mid-90s.

More below the cut.

It was the dawn of the fifth generation of video game consoles. Sony's PlayStation, Sega's Saturn, and Nintendo's N64 (the three consoles of this generation that mattered, and that are worth remembering as more than a footnote) were collectively the vanguard of 3D graphics in game design. Blocky and pixellated as a lot of those games look, believe it or not, it was an exciting time to be into video gaming. Boundaries were being pushed. New genres (such as survival horror) were being invented. And many developers were struggling mightily to find ways to translate their existing franchises into three dimensions.

TV Tropes refers to this phenomenon as the Polygon Ceiling. Some series, such as Final Fantasy, had a relatively easy, painless transition into 3D. In fact, RPGs broadly speaking weathered the change with few growing pains, if any. The main reason for this, I think, is simply that the mechanics that defined an RPG had very little to do with how those kinds of games were presented, in terms of graphics. The switch from 2D to 3D didn't really change anything about the essence of an RPG, and in most cases was actually beneficial.

The same was not true of more action-oriented titles, such as Mega Man, or Contra, or Ninja Gaiden, or... well, Castlevania. For an RPG, the way a player and the player's character(s) interacted with the world was fairly rudimentary, and the specifics were largely (in most cases) inconsequential. But in an action game, the player's interaction with the game's world is everything. Running, jumping, shooting, slashing, exploring, commandeering vehicles... The feel of these things was every bit as important as how they looked. And the specific details of the mechanics were important. Does the character have a life bar, or do they die in one hit? Can they control their jump mid-air, or are they committed once they launch themselves? Is the game a side-scroller, or a top-down action game? Is there a lot of jumping and verticality to the environments, or is it largely a horizontal affair? And so on, and so forth.

The transition to 3D presents a couple of problems, then.

Problem one is a pet theory of mine: 3D gaming compels a certain adherence to reality, at least notionally. I think that, subconsciously, players are better able to accept the more abstracted characters and environments of a 2D game because its nature as a 2D game means it is not operating in a space the player can recognize as real. So the abstractions – things like floating platforms, massive leaps, double-jumping, etc. – don't really seem troubling. But 3D environments have to look, if not realistic, then at least plausible given the restrictions or abilities of the setting. Platforms hanging in mid-air are an abstract thing that's du rigeur in a 2D game, but they look really weird in a 3D game without some kind of justification.

Problem two is less theoretical: 3D gaming requires a from-the-ground-up re-think of level design. Part of the reason the level layouts of a 2D side-scrolling game work at all is that the player has that side-on perspective that lets them see what's over the next rise, and react or plan their movements accordingly. 3D games generally don't allow for that, unless they're going for what's referred to as 2.5D – 3D graphics, but levels laid out and played the same as if they were in 2D. The reason this is a problem is the domino effect it causes. If you're re-designing the levels, you also have to re-design the way the player interacts with them. The player character's moveset has to change to accommodate this new setting. And then you have related problems to solve, which were never an issue in 2D games, such as camera control.

In essence, taking an established series from 2D into 3D changes everything. The environments, the way the player character interacts with said environments, the character's moveset, and the pacing. Meanwhile, franchises tended to be built on a certain consistency. You tend to buy a Contra or Castlevania or Mega Man game because you know what those games are like. The name indicates a certain kind of experience. So, the dilemma: How do you change literally everything recognizable about your game while preserving the essence of the experience so as to maintain continuity with what the franchise is all about?

Outside of Nintendo's major first-party franchises at the time, most of the heavily action-oriented series that were already big when the 3D revolution either:

Stayed 2D, and saw diminished exposure and popularity as a result (some went portable)

Went 3D, failed (sometimes after multiple tries), and died out in a console generation or two

Which brings us to Castlevania, and the fork in the road.

So, like most developers in the mid- to late 90s, Konami was trying to find ways to make their existing franchises work in 3D. This was at some point before Metal Gear Solid became their major cash-cow franchise.

Castlevania was a proven money-maker for them in the U.S. About the only entry they'd left in Japan had been Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, mainly because it was a game for the TurboGrafx-CD, which was doing almost nonexistent business in the States, and had been from its beginning. Which is a shame, really, because Rondo of Blood was damn near perfect. The Super NES conversion, Castlevania: Dracula X was good in general, but paled in comparison. But we'll come to that.

So naturally, the thing to do with their big franchises was to make them over in 3D. Which is exactly what they were doing with Castlevania on the N64. The result, Castlevania 64, was to be the the definitive statement of the series on modern consoles.

It... didn't work out that way.

Castlevania 64 went on to become one of the defining examples of what it meant to hit the Polygon Ceiling. Later that same year (1999), Konami brought out Castlevania: Legacy of Darkness, which expanded on its ideas and made some improvements, but still wasn't all that well received. But there was this other game that came first...

Koji Igarashi, a programmer at Konami, had put together a B team and gotten permission to make his own spin-off Castlevania game for the PlayStation, titled Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. It was going to be a 2D game, so Konami didn't put much effort into marketing or advertising it, at least not in the U.S. I don't know about elsewhere in the world, but in the U.S. at least, there was a certain drive to leave 2D gaming behind in favor of 3D. A certain amount of this (it's difficult to say how much) was admittedly driven by the console manufacturers and software publishers themselves, in an effort to sell more games by making said games look as cutting-edge as possible.

But gaming in 3D was in a transitional state. And most transitions are ugly and awkward. Two-dimensional games like Symphony of the Night or Rayman or Silhouette Mirage lacked a lot of the immediate wow factor that 3D games possessed; they were an iteration on what had come before in a generation when everyone was fixated on what was new and shiny. But at the same time, they had the benefit of established technique. Developers had at least two console generations' worth of history to draw upon when it came to designing a 2D game, to help them understand what worked or didn't work, and why. Many conventions of game design had been pioneered in the 8-bit days – the third console generation – and had been refined in the fourth generation. This fifth generation and its newer technologies offered the opportunity to refine it further still.

Time has been unkind to many of these early 3D efforts. However impressive most of these games looked upon release, many of them have aged poorly. With controls that are often both clumsy and awkward, and with graphics that frequently looked rudimentary even one console generation removed, they can be hard to go back to. And I say this despite all my intense personal nostalgia for games in this period. Two-dimensional games, meanwhile, have frequently aged much better.

Symphony of the Night, for example, which went on to become the face of the Castlevania franchise.

It's a little strange to think about Symphony of the Night being the odd one out, nowadays. It, and all the portable games that chased after its success and were to varying degrees crafted in its image, became what the franchise was known for in the end. There's a reason the genre is called "Metroidvania". But this was where all that began, and as a non-linear exploration-based side-scrolling game with RPG elements, Symphony of the Night seemed like a weird fit for the series at the time it came out.

There was some precedent for this in the series prior. Castlevania II: Simon's Quest had seen the player character traversing the Transylvanian countryside looking for bits of Dracula in order to unite and destroy them, and thus break the curse upon him. It was also a non-linear and exploration-based side-scrolling game. However, it was bad at communicating with the player and providing the necessary clues to make sense of its challenges. Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse, meanwhile, featured multiple routes through its levels by the simple expedient of giving the player a discrete choice at the end of most stages leading up to Dracula's castle. Rondo of Blood featured multiple paths, but presented them more organically, by having branching pathways and hidden routes in the levels themselves, which often led to different subsequent levels when pursued.

But all of these were mere flirtations with the idea of exploration compared to the sprawling, open mass of content that was Symphony of the Night.

Likewise, the series typically featured physically imposing, practically barbarian heroes before. Symphony's immediate predecessor, Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, had about the most characterization the series had seen in any of its heroes with Richter Belmont, who went on his adventure not only because Dracula was a bad, bad man, but also because he had kidnapped Richter's fiancee (along with a few other village girls, and a young lady named Maria Renard, who could also be played once rescued).

In place of the usual pseudo-barbarian hero, Symphony instead features a new playable character, Alucard, Dracula's half-vampire son. His true name, according to the manual, is Adrian Farenheits Tepes (yes, really), which... I can't decide whether that's awesome or ridiculous. Anyway, he goes by Alucard, which of course is his father's name spelled backward, to symbolize his opposition to his father.

Alucard first appeared back in Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse, which Igarashi has stated was his favorite game in the series. There, Alucard was one of three possible partner spirits the main character could recruit, after first facing him as a boss enemy. In that game, Alucard had a weaker version of his father's trademark triple-fireball attack, and the ability to turn into a bat and fly to locations other characters couldn't reach (at the cost of a constant expenditure of special weapon ammo). There, he was probably the least useful of the three partner spirits. His bat transformation was really helpful in only a small number of situations, and his attack was weak even when powered up to the three-shot version, unless you could make all three shots hit the same target. And like all the partner spirits, he was more fragile than the main character.

He's appeared elsewhere in the series since. In addition to an appearance prior to Symphony in one of the old-school Gameboy entries, he also shows up (under the alias Genya Arikado) in Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow for the Gameboy Advance, as well as in Castlevania: Dawn of Sorrow for the original DS. His appearance in Symhony of the Night led to a change in how its heroes looked. Character designer Ayami Kojima has a far more shoujo design sensibility, and as a result the franchise's leads have tended toward being more slender and androgynous ever since, even in the games she didn't design characters for.

But getting back to Symphony of the Night, Alucard was the perfect character for what Igarashi had in mind for the game. Both in his personal identity and in the kind of character he was, he represented something altogether different from the series norm: a slender, impeccably dressed nobleman in place of a broad-shouldered, leather-clad warrior; a cold, remote swordsman over a muscle-bound whip-swinger. He served as much as anything else to communicate that Symphony of the Night was headed in a different direction from the rest of the games up to that point.

Most games in the series were fairly typical for side-scrolling action games. Enemies tended to be weak defensively, but packed a punch, and were intended to soften you up for the bosses. You had your standard layouts of platforms to navigate between, with spike traps and instant-death falls into bottomless pits as punishment for bad timing of your jumps. Your player character did not grow as the game progressed: You had a single weapon with which to attack the enemies, though Castlevania allowed you to supplement this with sub-weapons, which you could find scattered throughout the game's stages, and which required ammunition to use. The game, meanwhile, grew in difficulty as you progressed, requiring you to hone your skills as you went. What was unique about Castlevania was its difficulty (its particular mechanics put it on the high end of fair, for the standards of the day) and its medieval/gothic horror setting.

Symphony of the Night is still a side-scrolling game, but that's essentially where the similarities end. Igarashi took a page out of the Metroid playbook, and crafted a non-linear, exploration-based action game. Then, for good measure, he bolted on some basic RPG elements. So rather than a linear march to the endgame, the player is allowed – encouraged, even required! – to explore every nook and cranny, gradually acquiring new weapons and abilities as they go, and to revisit old locations with their new-found powers and abilities in order to open up new pathways.

Yet for all the ways it's different from the series that sired it, Symphony of the Night leaned more heavily on the (admittedly somewhat anemic) series lore than any game had previously.

Rondo never saw release in the U.S., which is a goddamned crime, even as I understand perfectly why Konami passed on localizing it. What we got instead was Castlevania: Dracula X for the Super NES (known as Vampire's Kiss in Europe). This version of the game has some interesting trade-offs going on. The graphics are somewhat better, since it's a Super NES game. However, the music, while nice, doesn't hold a candle to the CD soundtrack featured in the original game. It also loses out on the multiple routes that were perhaps the defining feature of the TurboGrafx-CD version, which seems more questionable. The result is something that feels very much like a bright, shiny consolation prize.

Symphony of the Night is set in the 1790s, about five years after the events of Rondo of Blood. Alucard himself first appeared in the fifteenth century during the events of Castlevania III, so he's been around a while already; Symphony is therefore tied to two different games in the series. But as much as there was a shared continuity between installments, their taking place a century apart meant that none of them really required you to have played the previous installments to appreciate the current one. It isn't the first game in the series to revisit a particular point in time and set of characters – the very first sequel did it, after all – but it is the first to show real growth of any kind in those characters. Richter returns in a startling reversal of his original role as vampire hunter, and Maria Renard is all grown up and looking to take care of things on her own. And while it's true that you still really don't need to have played Rondo of Blood to enjoy Symphony of the Night, there was that added layer of interest for fans of the previous game.

Among the many other things Symphony gets right is its gameplay. Overall, the game is a little on the easy side, but that's easy to forgive. One of the things that makes it easy is simply its design. As an exploration-based game rather than a linear side-scroller, a lot of the traditional instant-death traps (such as bottomless pits) really don't make a lot of sense from the standpoint of environmental design. Punishing the player's bad timing is basically antithetical to the design of a game like this. The challenge lies far more in figuring out the correct path to the end, instead. Instant-death scenarios would be deeply unfair in that context. Instead of running a gauntlet, the player is navigating a labyrinth.

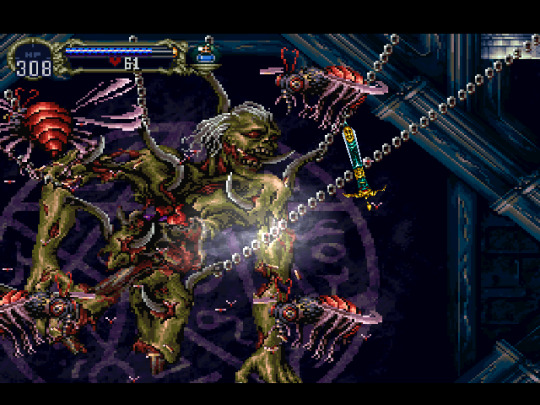

As befits a game that takes up as much geographical space as Symphony of the Night does, the enemies show wide variation in shape, size, strength, and tactics. Their placement is likewise well-considered. Enemies of the same type only rarely occupy more than one region of the game's map, giving each region its own ecosystem. Many of them pose little threat, playing into the relative easiness of the game. They're there because fighting them gives you something to do as you traverse the castle. The real challenge is finding your way through... and, of course, fighting off the bosses.

While many of the bosses pose only a middling challenge, a few encounters are genuinely harrowing, and many of them – Olrox, Granfaloon, and Galamoth, just to name a few – make for fantastic setpiece fights.

In addition to its gorgeous and varied environments, Symphony also offers the player several different powers and abilities. Over the course of the game, Alucard gains access to powers that allow him the classic vampire transformations (into a wolf, bat, or mist) which are essential for navigating the environment. This is in addition to abilities such as double-jumping and being able to walk underwater. There's also a multitude of weapons the player can find, with a variety of abilities and drawbacks, as well as several with hidden moves.

The only place the game really falls apart is in its second half. After uncovering enough of the castle to find a particular item, then player can then face off against the seemingly final boss, only to discover that this boss isn't so final as previously believed. In fact, it's just the halfway point. The game then reveals that there is an entire second castle to explore, where the real final boss is hiding. This is great in theory.

In practice, it’s somewhat less great. The second castle is a mirror image of the first; take the castle, rotate it 180 degrees, and you have the second half of the game. The problems here are manifold.

It's not as interesting to explore, because you've seen all this before. The color palettes are altered in much of the reverse castle, but the layouts are otherwise exactly as they were in the first castle, right down to all of the secrets. But at the same time...

It's disorienting, because while essentially familiar, it's also upside-down. It constantly messes with your ability to navigate without constant reference to the map. And while it would be nice to praise clever level design that works both right side-up and upside-down, the fact that you can double-jump, high-jump, and fly means that pathfinding is trivially easy no matter which way the environment is pointed. And since you already have all the essential expansions to your moveset...

There's less to get excited about. Part of the appeal of any good Metroidvania game is the player character's slowly evolving moveset, which allows increased exploration of the game's environment. There's a small thrill at the "Ah-ha!" moment when you realize that your double-jump or ability to fly or turn into mist will allow you to access an area you couldn't reach previously, either granting access to new areas or to yet another new power-up, expanding your moveset further. But that sense of excitement goes away since you already have all the essential maneuvering capabilities. It also means...

Since you've already acquired all your essential abilities, there is no direction suggested by limitations upon your movements, as there would usually be in a game like this. Most Metroidvanias are structured so that there are initially only a few places you can go, with tantalizing hints of what might lie beyond currently accessible regions. Thus, while you're free to explore in the reverse castle, the lack of growing capabilities means every direction is arbitrary. You spend the whole latter half of the game just going wherever, because one direction is as good as another.

While the game still never gets really hard, the difficulty does spike in the inverted castle. Unfortunately, it does this mainly by just making the enemies give and take more punishment. Monsters who served as minor bosses in the first castle now show up as basic enemies. As a result, the game slows down as you slog your way forward.

The thing is, this doesn't make Symphony of the Night a bad game. It does mean the latter half falls apart a bit, and is somewhat disapointing as a result. Most of the time, when I play through it these days, I tend to stop once I reach the inverted castle. The level of novelty adn inventiveness on display throughout the first half tapers off pretty abruptly in the second half. But it's still overall a vastly entertaining game, and one that I love. It’s worth playing through by basically anybody.

Inverted castle aside, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night was a smash hit. It was one of the first PlayStation games I ever bought, somewhere in the spring of 1999.

I remember suddenly recalling, out of the blue one day, that I'd read about a Castlevania game for the PlayStation that was a little different from the rest of the series. That was it. I knew it existed. So renting it seemed like the safest bet.

The problem with rentals, of course, is that after the end of the rental period, they actually do expect you to give it back. And that was a problem, because after just about half an hour spent playing the game, I decided that this was one of the most phenomenal games I'd ever played. It went without saying that I wanted to own it. In fact I wound up picking up a copy that night (technically, it was after midnight, so that would really make it the following morning) for $20 at a Wal-Mart that was open 24 hours. I returned the rental the next day, since I wouldn't be needing it any more.

Really, I think I knew I wanted to own this game the moment I got into the Alchemy Laboratory, the second main area, and the first that really allowed for some exploration at the very beginning. It was perhaps the first area where everything I loved about the game came together perfectly: the graphics (lushly detailed and lovingly animated), the environments (big, eclectic in theme, and interesting to look at), and the music (as eclectic as the environments, beautifully orchestrated and arranged).

I still wind up digging into it for at least a little while every year – and, yes, it's usually around Halloween that I do. I don't usually go through the inverted castle, as I mentioned before. I have stuff to do, and my enthusiasm usually wanes around that point. But I did it this year, for old times’ sake.

It’s always a pleasure playing Symphony for the little details here and there throughout the game. But I especially took notice playing through it earlier this month, since I was playing it to finish it, and to take a more critical look at it.

For all that the PlayStation is routinely (and, let's be honest, correctly) assessed as a system with anemic 2D capabilities, Symphony of the Night is a 2D powerhouse for the standards of its day. And as pixellated as it looks when viewed on HD TVs or monitors today, it still looks fairly amazing.

There are all sorts of tiny details that work to sell the environments of the game as places with their own distinct identities. Birds nest in the belfries of the Cathedral. The frozen-over sections of the underground caverns have a thin skin of ice on the pools of water there, which will break off, a bit at a time, as you collide with them. Then you have the rats doing their rat business in the little inaccessible nooks and crannies of the Outer Wall. For that matter, the Outer Wall's weather will randomly change whenever you enter it: It can be clear, foggy, or raining. There's no effect on the gameplay; it's purely for effect. Then there's the way many enemies (not just bosses) have unique and involved death animations. This is on top of them being already highly detailed as it stands. And these enemies are rarely repeated throughout the game. Each area has its own unique ecosystem of enemies which aren’t often found elsewhere in the game. Seeing the full range of the game’s bestiary is in fact one of the few real joys of exploring the inverted castle.

The only part of the game that’s aged somewhat less gracefully is its 3D graphics, which thankfully don’t matter too much. There’s actually very little 3D in the game proper, and what’s there is used either as background elements (rushing clouds in the Cathedral and Clock Tower areas, and the clock tower itself), or as a supplement to the 2D graphics (the ice crystals that the Ice Maiden enemies use to shield themselves or shoot at you, the pulsing lake of lava, etc.). About the only instance of 3D where I cry foul is the wings of the giant bat. Those are honestly kind of embarrassing. Everything else is fine, if a bit low-fi. But I find myself getting pretty nostalgic for that, honestly.

Still, as easy as it is to get wrapped up in extolling the virtues of Symphony of the Night’s technical mastery, what should be kept in mind is that buried under all the flash is a solid game. Like the best Metroidvania titles, it challenges you not through your steel-trap reflexes but by your ability to navigate the world, to find the correct way ahead, to ferret out the secrets necessary to success. Unlike its predecessors, it presents not a gauntlet to be run, but a puzzle to be solved.

Because it amuses me, let’s take a look at some of the localization oddities of Symphony of the Night.

Someone at Konami – I'm about 80 percent sure this was someone on the localization team, not the original Japanese development team – was hell-bent on inserting fantasy and sci-fi literature references into the game.

The boss Granfaloon takes its name from a word invented by Kurt Vonnegut in his book Cat's Cradle. It's used to describe a collective of people whose commonalities might seem to be significant factors in their association, but which are in fact meaningless in the grand divine plan. This boss shows up in at least one later game (Aria of Sorrow), and is renamed to the more-appropriate Legion.

There's a handful of references to The Wizard of Oz, of all things. These come in the form of three different enemies: a scarecrow who jumps around fairly brainlessly, an enemy called Tin Man which is essentially a steam-powered machine full of blades, and an enemy called simply Lion which is described as being cowardly.

And then there are the references to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion...

This will be easier as a list:

The Nauglamir: In-game, it’s a necklace that raises the player’s defense. In The Silmarillion it’s a necklace made by the Dwarves for the Elvish king Thingol, which among other gemstones contained one of the Silmarils – a gem (out of a set of three) containing vast but frustratingly vague magical powers.

The Sword of Hador: In-game, it’s described as belonging to the House of Hador. This is a reference to The Children of Hurin, which is one of the main tales of The Silmarillion, and more recently was expanded into a book in its own right. The House of Hador is more famous for its dragon-crested helmet, but the game has a dragon helm as a major piece of Alucard’s equipment already, and the developers probably didn’t want to name one of the more important items after something in an intellectual property they didn’t own.

The Fists of Tulkas: In-game, they’re a set of gauntlets to be equipped for punching enemies. Tulkas in The Silmarillion is a god-like being whose area of divine responsibility is war.

The Mormegil: In-game, it’s described as a black-bladed sword, and by its statistics, it’s especially powerful against holy-aligned enemies. In The Silmarillion, it’s a sword used by Turin Turambar, of the House of Hador (though it’s not an heirloom of said House), which does indeed have a black blade, and a sinister past.

The Ring of Varda: In-game, it’s a ring that gives stat bonuses to the player. In The Silmarillion, Varda is a goddess of sorts – the queen of the highest tier of divine beings, just below the creator – who is associated with the stars.

Azaghal: In-game, a unique enemy who appears in exactly one location (the inverted version of Olrox’s quarters, for the curious). He is an enormous glowing phantom who swings a sword that’s at least twice the size of the player’s character. In The Silmarillion, he’s a Dwarvish king slain in battle by a dragon. He has a dragon-crested helm which is given to one of the Elvish princes after his death, which is the same helm that ultimately becomes the heirloom of House Hador, after changing hands a few times.

The Crissaegrim: In-game, it’s the most game-breakingly powerful sword the player can find, being a sword that strikes four times in the amount of time most other swords take to strike once, strikes diagonally upward and downward on two of its strikes, and has the best reach of any of the game’s other swords’ standard attacks. And you don’t have to stop moving to swing it. In The Silmarillion, it’s a mountain range where the Eagles dwelt. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, it no longer exists, having sunk into the sea along with much of the land where The Silmarillion takes place.

Castlevania has always borrowed from pop culture to some extent. The original game borrowed its boss monsters from classic horror movies and literature (Dracula, Frankenstein's monster, and the mummy), and its sequels up to this point borrowed still more. But the specific things being borrowed in Symphony of the Night have always struck me as weird. There's something a bit more... universal? (pun unintended) about Dracula or the mummy or the wolf-man or Medusa or... The list goes on. The Silmarillion and Cat's Cradle and The Wizard of Oz are more puzzling, at least to me. Maybe it's just that they're not in the public domain (well, The Wizard of Oz is; the book, at any rate). Maybe it's because they're not as firmly in the horror genre themselves, or even horror-adjacent.

The success of Symphony of the Night helped propel Koji Igarashi to the position of de facto steward of the franchise. After Konami's double failure to craft a worthy Castlevania in 3D on the N64, they decided to go smaller-scale for the series, at least for a few years. The next game, Castlevania: Circle of the Moon was released in 2001 for the Gameboy Advance. While it wasn't directed by Igarashi, it clearly aped Symphony of the Night in most respects. Regrettably, its overall quality wasn't one of them. Igarashi returned to the director's seat for the next several games in the series. He got his band back together (Michiru Yamane on music, Ayami Kojima on character designs) for Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance, which has a somewhat divisive reputation among the fanbase. The follow-up, Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow, is often considered to be the first truly worthy successor to Symphony. The following games on the DS – Dawn of Sorrow, Portrait of Ruin, and Order of Ecclesia – saw diminishing returns.

Igarashi's success with his Metroidvania titles in the series eventually saw him put in charge of a new attempt to make Castlevania in 3D. The results, Castlevania: Lament of Innocence and Castlevania: Curse of Darkness on the PlayStation 2, were... competent, at least. I’ll probably talk more about those another time.

The Castlevania franchise ultimately got farmed out to Mercury Steam, a Spanish developer, who took the series in a different direction (though one of their games is at least to some extent a Metroidvania in Igarashi’s mold).

More recently, Igarashi's gotten back in the saddle. While he's no longer with Konami, he's been toiling away on a Kickstarter project called Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, which follows aggressively in the footsteps of his Metroidvania games. His initial Kickstarter pitch leaned heavily into his success with the Castlevania franchise. While Ritual of the Night has yet to be released, his team put together a faux-8-bit homage to Castlevania III titled Bloodstained: Curse of the Moon, which seems to be positioned as a prequel to Ritual of the Night. It's fantastic, and is available for PC and all current consoles.

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about Symphony of the Night; I should probably discuss its availability for whoever is curious. I’ll break this down by systems.

Sony: By far, Sony’s systems have the widest availability for this game. The original PlayStation disc can be played on a PlayStation, PlayStation 2, or PlayStation 3, or via any halfway decent PlayStation emulator on PC. Almost any computer you can buy today will run PlayStation games just fine with emulation. In addition, this same version is available digitally as a PS One Classic on PSN, so you can download it version for the PlayStation 3, PlayStation Portable, PS Vita, or PS TV. Like most single-disc PlayStation games on PSN, it runs about five dollars. Then there’s Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles. This is a PSP release whose main purpose was to be a shiny new 2.5D remake of Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, a.k.a. Castlevania: The One That Got Away for many years in the U.S. However, you can easily unlock Symphony of the Night in it (as well as the original TurboGrafx-CD version of Rondo of Blood). This version of Symphony features a new voice cast and a rewritten script, which may or may not recommend it. The original game was never going to be High Drama even in some theoretical ideal form, and the original script and hamtastic acting at least gave it a kind of B-grade charm. As it stands, the newer version’s acting is more professional, but loses some of that overwrought but undersold charm. However, it's completely serviceable, and the fact is that all three games in the collection make it well worth a purchase. It's available physically (for PSP only) or digitally (for the PSP, PS Vita, and PS TV). Finally, there’s Castlevania: Requiem, a combo pack for the PS4 which contains both Symphony of the Night and the TurboGrafx version of Rondo of Blood, with the English translations and voice work from the PSP release. These updated versions of the game feature a new song that plays over the ending credits (more on that below). Castlevania Requiem also allows you to enable filters to soften the sharpness of the image, or to play it stretched fullscreen as well as in the original 4:3 aspect ratio with a variety of frames for vertical letterboxing.

Microsoft: An HD remaster of Symphony of the Night came out early in the Xbox 360's lifespan for Xbox Live Arcade. It offers a smoothing filter for the graphics, and a frame for the vertical letterboxing (the game itself is still presented in 4:3 aspect ratio with no option to stretch the image). The script and voice acting are the same as the original version. There are two brief CGI cutscenes in the original version of the game which were cut from this version to save disk space (originally, Xbox Live Arcade titles had to come in under a certain size limit), but nothing of value here is lost. The music for the ending credits has also changed from the original version. The original song, "I Am the Wind", was replaced with a new piece due to licensing issues. Again, personally, I think nothing of value was lost. "I Am the Wind" sounded tremendously out of place, tonally, compared to the rest of the game. In addition to the Xbox 360, this version of the game is also playable on the Xbox One via backward compatibility.

Nintendo: Nothing, sadly. The closest Nintendo ever got to this game was having a near-perfect port of the Japanese version of Rondo of Blood on the Virtual Console, but the VC's basically shut down at this point. You can still download games you've already purchased, but new purchases are no longer possible.

PC: No official release of Symphony of the Night has occurred on PC, despite it being an excellent candidate for Steam, because Konami is a shit company run by shit people, and they've decided to leverage all their intellectual properties for pachinko machines these days, which is a very shit thing for them to be doing. Your best bet for PC is to get the PlayStation disc and download an emulator.

#castlevania#symphony of the night#halloween#effortpost#deep dive#video games#video gaming#gaming#castlevania symphony of the night#castlevania sotn

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Off the Shelf: Still kicking

MICHELLE: Melinda, after we finish this one we will have done as many columns in 2019 as we did for the entirety of 2015-2018! Go us!

MELINDA: *laughs weakly* Yes… “go us.” Um. Wow. When you put it that way, we sound terribly unimpressive.

MICHELLE: Well, the alternative would’ve been to let it disappear, so I think we deserve a bit of credit for resuscitating it! Anyhow, I expect that you’ve been reading some manga!

MELINDA: I suppose you’re right! WE ARE BASICALLY GODS.

…

Okay, maybe not. But yes, I have indeed been reading some manga, or at least rereading, which is to say that I took some time this week to look at the new omnibus edition of CLAMP’s four-volume manga, Wish, originally published in Kadokawa Shoten’s Mystery DX, adapted into English in the early 2000s by TOKYOPOP, and resurrected just a few weeks ago by Dark Horse Comics, with their usual omnibus treatment—larger trim size, very nice-looking print, and a somewhat refreshed translation.

For those who missed Wish the first time around, it’s the story of an angel, Kohaku, who has been sent to Earth to find Hisui, one of the four “Master Angels” (why they don’t just say “Archangel” is a mystery to me, but maybe there’s something I don’t get), who disappeared from Heaven after a visit to the bridge between Heaven and Hell. During their mission, Kohaku—who appears human-sized during the day but reverts to tiny cherub form at night—is rescued from an attacking crow by Shuichiro, a local human doctor. Complications ensue when it turns out that Hisui actually defected to Earth in order to be with Kokuyo, the actual son of Satan, with whom they have fallen in love. Meanwhile, Kohaku becomes confused by their own growing feelings for Shuichiro.

There’s a whole lot packed into this short series, including more angels and demons, time travel, reincarnation, messenger rabbits, cats (some of whom are actually demons), and a tree fairy, but generally speaking it’s all just incredibly CLAMP from start to finish, and if you’re into that, you know what I mean. Someone even sacrifices an eye. This thing honestly couldn’t get any CLAMPier. It’s not my favorite of their series—I could live very happily never reading another manga about angels for the rest of my life—but as most CLAMP fans will know, the big deal about this edition is the translation, which is certainly what caught my attention.

In CLAMP’s original vision, there is no gender in Heaven or Hell, but in early 2000s publishing, it was unthinkable to convey that in English, especially when it came to the angels, who, in Japanese, referred to themselves with genderless pronouns. This led to a decision to choose genders for each of the angels, based on heteronormative standards regarding appearance and romantic entanglement, outraging some fans but satisfying style guides. Fast forward to 2019, when publishing has finally recalled that singular “they” is a thing, and our angels are genderless at last.

I’ve already mentioned that Wish is far from my favorite of CLAMP’s work, so I wasn’t especially eager to reread it, but I was surprised to note just how much more enjoyment I got out of it this time around. As someone who identifies as nonbinary, I realize this may be of greater importance to me than most, but whatever CLAMP’s intention really was when they filled their comic with genderless angels, it feels like representation, and for something originally published in the 1990s, that is kind of a big deal. Freeing the angels from gender expectations breathed new life into them for me, made the story richer, and opened up its universe to the notion that love and attraction might be based on something other than a person’s gender expression or whatever reproductive organs they happen to possess. These are not novel ideas for many of us, but with all the hand-wringing over this series back in 2002, it feels revolutionary. Mostly, though, what I’m struck with as I read this edition, is how easy it would have been to publish it exactly as it is now, then. The sentences are not awkward. There is nothing that feels labored or unnatural in this translation. How has it actually taken publishing this long to figure that out?

MICHELLE: It’s been a long time since I read Wish, and it was also not my favorite, but I definitely feel a greater spark of interest when I imagine a translation that represents the angels as genderless! It makes me want to shake TOKYOPOP and demand, “Would that have been so hard?!?!” (They had other similar issues back in the day, too, and not just with genderless protagonists. I distinctly remember a character in GetBackers being assigned feminine pronouns when, in fact, he is very much a dude and if anyone had actually bothered to learn anything about the series they were translating, they would’ve known that. SIGH.) I can totally see how it would make the whole story richer as a result.

MELINDA: Yeah, nobody could be more surprised than I am to be describing Wish as “rich” in anything other than CLAMP’s beautiful, swirly artwork, but I genuinely enjoyed rereading it, and I’d even recommend it, at least to fans of shoujo manga, and particularly to other enbies. It’s an unusual treasure of representation for the time period. And messenger bunnies! Who doesn’t love messenger bunnies?

There is one jarring panel in the first volume, where one of the demons seems to misgender Kohaku as “she,” but I don’t know if that was an editorial oversight (that’s how it’s translated in TOKYOPOP’s version, too) or if it was actually written that way in Japanese. But in over 800 pages, that one panel wasn’t significant enough to mar my enjoyment overall.

So what did you read this week, Michelle?

MICHELLE: Maybe that demon was intentionally being a jerk.

I checked out the first volume of Hitorijime My Hero by Memeco Arii, one of the first boys’ love manga published in print by Kodansha Comics. (They did release a handful of others digitally in 2018.)

As a kid, Masahiro Setagawa hated tokusatsu shows because he knew that, no matter how miserable his life was, no hero would come to save him. But when he fell in with a group of delinquents in middle school and became their gofer, a hero did come in the form of Kousuke Ohshiba, the so-called “bear killer,” who defeated the thugs and ended up with Setagawa as his new underling. Setagawa befriended Ohshiba’s younger brother, Kensuke, and as the manga begins, some time has passed. He’s dealing with the fact that Kensuke is now in a relationship with another boy named Asaya Hasekura and that Kousuke is a teacher at their high school.

Almost immediately, Kousuke is confronting Setagawa about the feelings he believes Setagawa has for him, saying, “Even if you feel that way I won’t be able to return those feelings.” Setagawa is too dumbstruck to deny it, and then Kousuke (an adult) keeps sending him (a teenager) mixed signals, like suddenly smooching him or calling him “the guy I like.” It turns out that Kousuke is basically trying to make Setagawa realize he is gay. This eventually works. And then they do it. Eyeroll.

Because this series is a spinoff from an earlier series, we’re just kind of thrown into a confusing timeline and a mix of characters without a lot of context. I’ve seen the first couple of episodes of the anime, and they handle all of this material far more clearly. The manga does a little to show why Setagawa likes Kousuke—he’s strong, smart, and capable—but none at all to show why Kousuke likes Setagawa, aside from one page where he talks about how his devotion helped him retain his humanity or something. Really, it’s all pretty disappointing so far. I know it’s a popular series, so I’m hoping it gets better.

MELINDA: I can’t help but roll my eyes along with you. This basically sounds like a collection of my least favorite BL tropes, though maybe (hopefully??) at least without the younger, smaller guy wincing in pain and horror every time they have sex? Please tell me it at least doesn’t have that. Though maybe it doesn’t matter. I know the student/teacher thing is a common trope too, but I really hate it, especially when it’s the main romantic plot line. I know it’s a popular series, but I honestly can’t imagine reading it by choice.

MICHELLE: To its credit, it absolutely does not have that. It’s fully a fade-to-black scenario with some evidence afterwards that Setagawa enjoyed himself tremendously. As for the student-teacher thing, this is a slightly different variation in which the two people concerned knew each other for years before Setagawa came to the school where Kousuke teaches, so the power imbalance between them is not so much that Kousuke is in an official position of authority but that Setagawa has kind of idolized him.

MELINDA: Either way, I’m guessing it’s not for me. I’ll wait to hear what you think of future volumes before taking the risk.

MICHELLE: Okay. I can handle at least one more. Speaking of Kodansha’s advances into the realm of print BL, would you care to do the summary honors for our mutual read this time?

MELINDA: Sure!

This week, we both read the first volume of the much-anticipated series 10 Dance, by Inouesatoh, also from Kodansha Comics, as Michelle mentioned above.

The story involves two ballroom dancers with similar names—Shinya Sugiki, who is an international champion in Standard Ballroom, and Shinya Suzuki, who is the Japanese national champion in Latin Dance. Their relationship with each other is both admiring and rivalrous, and when Sugiki asks Suzuki and his partner to train with with him (and his partner) for the 10-Dance Competition (combining the 5 Standard and 5 Latin dances), Suzuki finds it impossible to refuse.

Over the course of the first volume, the four dancers train together—the men in particular working to be able to lead in each other’s specialty—and that’s literally all that happens in the story, but as we watch the two of them butt heads (and other things) throughout the training, it’s honestly just riveting. This story is all about personality and relationships, and certainly we’re expecting some steamy romance between the two male leads down the line, but even in this preliminary volume, where nothing overtly romantic happens, there’s so much interpersonal entanglement to enjoy.

The two men couldn’t be more different. Suzuki, who grew up in Cuba, has been dancing with his partner since childhood, while Sugiki changes partners constantly, never quite settling in with anyone. Suzuki’s strength is showing passion on the floor, while Sugiki’s is the elegance of his form. And though things are slowly heating up a bit, I honestly believe I would be happy just watching them dance together as I learn new details about Standard and Latin ballroom rules, pretty much forever. It’s that entertaining.

MICHELLE: I enjoyed it tremendously! From the start, the cover art reminded me of est em, and the content within does, too. With est em, I was always struck by the way her characters would talk while engaged in intimate acts, and although Sugiki and Suzuki aren’t having sex, they’re still engaged in physical activity—indeed, they’ve been dancing until dawn together for months—that puts them in close proximity, gettin’ sweaty, maintaining eye contact, et cetera. And they’re talking throughout, gradually becoming closer and revealing details about their personal lives in the process. I love the slow development of their relationship and how this, in turn, makes small moments so pivotal. The one that stands out is when Sugiki has gone to London to defend a championship title. When he succeeds, it’s Suzuki that he calls, and when this reserved man actually smiles when being told “Hurry up and come home,” it has such impact! Of course, they go right back to butting heads after that.

MELINDA: I agree on est em, though I’d go even further and say it feels like an est em/Fumi Yoshinaga hybrid, with the additional warmth of their observations about each other’s habits and idiosyncrasies and the scene where they dance together at a restaurant, because trying to make points about dance while sitting at the table just isn’t working. It’s got all of est em’s sexiness and suave, along with Yoshinaga’s warm goofiness, and the underlying elegance of both.

MICHELLE: “Warm goofiness” is a great way to describe the scene where Sugiki, frustrated by Suzuki’s attempts to lead the waltz, gets Suzuki to adopt the woman’s role and proceeds to very thoroughly make him feel like a princess. “I feel like I could pop out a dozen babies for you right now!” And you’re absolutely right about elegance, too; these dance scenes are drawn so beautifully.

If you’ll forgive somewhat of a non-sequitur, although I don’t know the kanji used for Sugiki and Suzuki’s given names (and, indeed, it might not even be the same), one definition for “shinya” has a meaning that’s very applicable to the story. Check it out.

MELINDA: I believe I read somewhere that the kanji for each of their names is slightly different from the other, but I’m tickled by that meaning all the same. It certainly is appropriate!

Bottom line, I can’t wait to read more of this series, and I’m thrilled that Kodansha brought it over for us!

MICHELLE: I enthusiastically concur!

Thanks for joining us for another installment of Off the Shelf! The winner of last column’s giveaway is Joseph Miller! Joseph, send over an email or drop a message to Melinda on Twitter to collect!

By: Melinda Beasi

0 notes