#source: thoma's second anecdote from this event

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

MORE THOMAMA LORE: her name is ulrike :D

#category 5 aster moment#thoma#source: thoma's second anecdote from this event#kaeya is there also :D#ALSO: ulrike joined the knights before kaeya did#also also: ulrike has high alcohol tolerance#scrounging lore about character's families like my cat begging for table scraps lol#according to kaeya ulrike is ''free-spirited and thoughtful“ + ''gentle and kind'' but he's kind of a notorious flatterer lol (i <3 him)

1 note

·

View note

Text

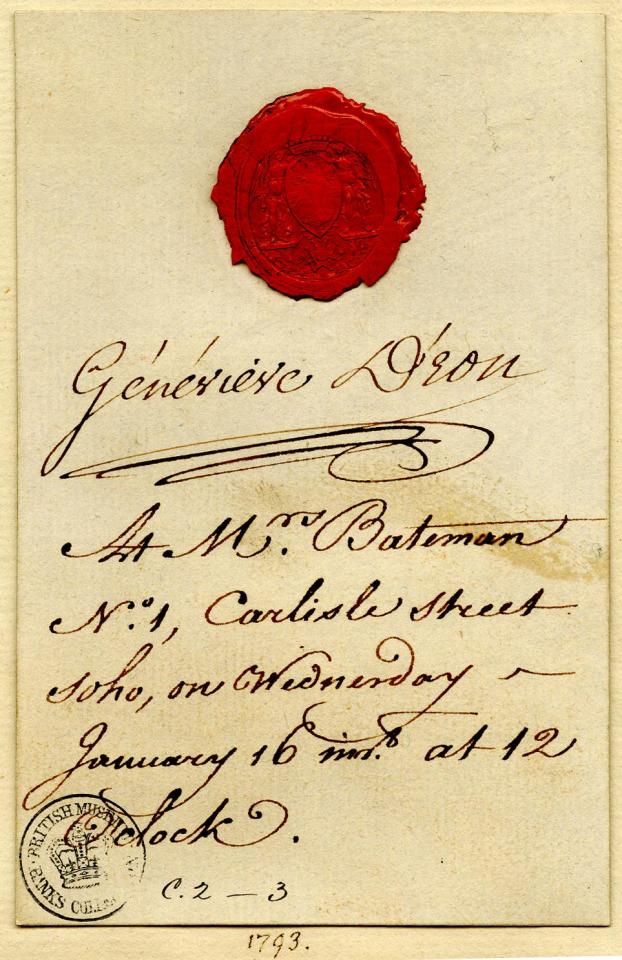

The Partnership of Mrs. Bateman and the Chevalière d’Eon

[Right: Mrs Bateman, print c.1793 by Marino or Mariano Bovi (Bova), after Ludwig Guttenbrun, via the National Portrait Gallery

Left: Mademoiselle La Chevaliere d’Eon de Beaumont, print c.1787 by Thomas Chambers (Chambars), after Richard Cosway, via the National Portrait Gallery]

Mrs. Bateman was an English actress, singer and fencer. In the 1790′s she traveled Britain with d’Eon putting on fencing displays. I could not find much about her life either before or after her partnership with d’Eon. Men and Women of Soho admits to having “not, at present, discovered the date of Mrs. Bateman’s birth or death.” (p6) However A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800 speculates she may have been Mary Bateman née Humphry (1765-1829) who was buried at St Paul’s, Covent Garden. (v1 p376-8) Certainly the dates and location seem to match up.

Its unclear how the two met, but its possible Bateman was one of d’Eon’s students. In August 1792 d’Eon had “opened a fencing School, which is much frequented by the younger Nobility.” (Evening Mail, 6-8 Aug 1792) A Biographical Dictionary of Actors... states that Bateman had been “D’Eon’s pupil since 1792” but it’s unclear what their source is.

The two were clearly acquainted by the 29th of November 1792 when the Morning Chronicle reports:

The Chevalier D’Eon and Mrs. Bateman are made honorary members of the Club d’Arms; so that these heroines, if they are not, like the Fernigs, fighting in the field of war, are at least preparing for the conflict. This is, however, very menacing-if our ladies take to the small sword, the constitution is undone.

Their professional association started in January 1793. Mrs. Bateman held a series of subscription breakfasts at her house in Soho. After breakfast fencing matches were held for everyones entertainment. Both d’Eon and Bateman fenced at these events. The Diary or Woodfall's Register reported that d’Eon complimented Bateman’s fencing skills describing her as “a youngling in her nest, that would rise and support the honour of female heroism in England.”

The World reported that 500 people attended the second event on the 16th. “At one,” writes the London Chronicle, “breakfast being finished, Mademoiselle assumed her former characters and sustained two assaults; the first with Captain Ross, an Irish gentleman, the second with Mr. Scott. It was allowed by all the company, that a greater display of science and dexterity was scarcely ever seen.”

The World reported that “the greatest display of sprit and science, were between Mr. Hill and Mr. Hume, Capt. Walslby, and Mademoiselle D’Eon.” Soho and Its Associations shares the following anecdote from the event:

Mrs. Bateman gave an elegant amusement to a party of about 500 ladies and gentlemen at noon. ‘Le Chevalier D'Eon fenced,’ says a newspaper of the period; ‘she sustained four assaults from Capt. Walmsley, and in the loose play refused a mask, saying, “I have defended my virginity fifty years without, and now cannot adopt it.”’

(see Diary or Woodfall's Register, 12 Jan 1793 and 18 Jan 1793; The World, 17 Jan 1793; the London Chronicle, 17 Jan 1793; Soho and Its Associations p72)

[Admission ticket for “Geneviéve d'Eon At Mrs Batemans, No 1 Carlisle Street Soho, on Wednesday January 16 at 12 O'clock.” c.1793, via the British Museum]

On Thursday the 30th of May 1793 Mrs. Bateman held a benefit night at the King’s Theatre in Haymarket. There was a performance of All in the Wrong. Mrs. Bateman played Lady Restless. Elizabeth Farren (who was rumoured to be Anne Damer’s lover) played Belinda.

“Mrs. Bateman was honoured last night with the appearance of a most numerous and splendid company. Every part of the Theatre was full, and the Boxes were decorated by and uncommon display of beauty and fashion.” Reports the Morning Chronicle, “After the play, the Chevalier D’Eon in generosity of friendship, displayed her wonderful talent in fencing. She first pushed carte and tierce with her youthful imitator, Mrs. Bateman.” D’Eon then fenced a gentleman. In preparation she “pulled off her jacket, and thus stripped to her stays,” reports The Times, “with her handkerchief loose over them, and short petticoats that did not come half way down her legs”.

“It is impossible to describe the wonder and delight of the House, at the agility and muscular strength displayed by the Chevalier,” reports the Morning Chronicle, “Mademoiselle D’Eon has lived long enough in England to adopt the most amiable traits in our manners, and she may be assured, that it will raise her in the esteem of the country she loves.”

The Sun was less impressed by the performance complaining that “the indecent circumstance of her stripping herself to her stays, preparatory to her fencing, gave a very general disgust.” The Times conceded credit to “the Lady’s science and activity” but was horrified “to see an old masculine woman of sixty thus attired, and publicly exposing herself on the stage,” declaring that it was “an indecency which we shall never suffer to pass by without a very severe animadversion.” And the St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post snipes that d’Eon gratified the audience’s “curiosity rather than admiration.”

(A full cast list can be seen in the advertisement printed in the Diary or Woodfall's Register, 25 May 1793; For reports of the event see: Morning Chronicle, 31 May 1793; The Times, 31 May 1793; Sun, 31 May 1793; St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 30 May - 1 June 1793.)

D’Eon’s next fencing match took place at Ranelagh on Wednesday the 26th of June and was against Monsieur Saniville. Saniville had previously fenced the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. There was considerable excitement leading up to the match. The Times reports that the event “engrosses at present the conversation of the beau monde. This extraordinary Lady has always been renowned for her skill in the art of Fencing, and from her attacking so capital a fencer as Mr. Sainville, she must still have the same ideas of her own superiority.”

So many applications were made for boxes for the event that the Managers of Ranelagh had to “inform the public that no preference can be given any more of that night than on any other” but they assured that “the Fencing Stage which is erected before the Prince’s box, is so situated that the Assault may be seen by the Company with the greatest conveniency.”

The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser reports that: “Mad. D’Eon hit her antagonist very often in the first assault; but that in the second she received many fine thrust from Mr. Sainville!” The Morning Herald reports that d’Eon displayed “a vigour and firmness incredible to her age.” and that Sainville’s “dexterity, easiness and the sureness of his thrusts, are so much increased since his last assault with Mr. St. George”.

(For the lead up to the event see: The Times, 24 June 1793; Morning Post, 22 June 1793. For an advertisement for the event see: Star and Evening Advertiser, 22 June 1793. For the message from the Managers of Ranelagh see: Diary or Woodfall's Register, 25 June 1793. For reports of the event see: Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, 28 June 1793; Morning Herald, 29 June 1793)

While d’Eon continued fencing, Mrs. Bateman had been improving as an actress. “Mrs. Bateman is in great estimation at Richmond as an actress.” Reports the Morning Post, “She has more exercise for her talents, and is of course, exceedingly improved.” (Morning Post, 21 August 1793)

On Friday the 23rd of August, 1793, the Theatre Royal in Richmond held a production of The School for Scandal followed by The Citizen. Mrs Batman played Lady Teazle in The School for Scandal and Maris in The Citizen. “In the course of the Evening, (by Particular, Desire of several Persons of Distinction)” reads an advertisement in the Morning Post, “The celebrated CHEVALIERE D’EON, Will FENCE with A NOBLEMAN.”

A reporter at the St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post was appalled by d’Eon’s attire:

A disgusting fight was exhibited on Friday Evening last, at the Richmond Theatre—the Chevalier D’Eon fencing with a gentleman. Her merit, as a fencer, is great; but we were hurt to see her displaying that merit on a publick stage, and in a dress that was scarcely decent. She seemed to have but one petticoat on, while a pair of immense pockets dangled on the outside. If she deems is prudent to make a publick display of her fencing abilities, would it not be better to reassume the dress of a man?

( Morning Post, 21 Aug 1793; Morning Post 22 Aug 1793; St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 27-29 Aug 1793.)

D’Eon and Bateman arrived in Brighton in late August. Reporting from Brighton, The World writes that on the 31st of August “Madam D’Eon is here renovating her strength by exercise and bathing.” And on the 1st of September “D’Eon, and Mrs. Bateman, are arrived here; the latter is to make her appearance in Lady Teazle and the Irish Widow, on Wednesday next; every place is already taken-It is hinted, that Mad. D’Eon is to fence. They are much courted by the fashionables.” The military camp near Brighton was excited by the prospect of the entertainment. Especially by the news that “D’Eon is to fence with an Officer of Brighton.”

On the 3rd of September Mrs. Bateman preformed in Bridget, the Chapter of Accidents and Widow Brady. “The Theatre last night was better attended than on any former occasion ever witnessed in Brighton-” reports The World, “Mrs. Bateman went through both her parts with the upmost spirit and vivacity, and received the warmest applause; the Performers in general went beyond their usual style of acting.”

D’Eon then fenced with an officer. “She was dressed in armour, with a helmet and feathers-” reports The World, “her antagonist, with all the advantages of youth, activity and a considerable share of skill, had the worst of the contest.” The Morning Post reports that “Several of the Militia Heroes fainted during the contest.”

(The World, 2, 3, 6, 7 & 9 Sept 1793; Morning Post 19 Sept 1793)

During their stay in Brighton, Bateman preformed at the Margate Theatre. “The two nights that the Chevalier fenced the house was crowded, a circumstance rather surprising at this time of year,” reports the Morning Chronicle, “but so improvident was the engagement which Mrs. Bateman made with Mr. Wells, the Acting Manager, that their profits were by no means sufficient to defray the expenses of their journey.” When the Duchess of Cumberland heard of this she began a subscription for d’Eon, who “was so affected that she even shed tears.” Mrs. Bateman presented to the Mess, a poem “said to be written by Wm. S----d, Esq”, which included the following lines about d’Eon:

Our heroine, who, with wondrous pow’rs of art

Has play’d thro’ motley life, full many a part;

And who, with equal ease and praise alike,

Can write a folio, or can trail a pike;

Can as a deep and learned Lawyer shine,

Or coolly try the diplomatic line;

Can, like Bellona, rage an actual war,

Or at fencing-match desporting spar;

Can a fine Lady’s airs and ease assume,

The admiration of a Drawing Room;

Who, with a courage yet untaught to yield,

Has mow’d down legions in the tented field;

Has the fierce Despot’s vengeance dar’d to brave,

And mock’d alike the prison and the grave;

And tho’ a host of Myrmidons attack,

Disdain’d alike the Bastile and the Rack.

But now, alas! our matchless maid appears,

For the first time, a woman-by her tears.

Nay, she e’en boasts them as tribute due

To that support she has received form you;

And, sobbing, thus requests me to impart,

The feelings of her charged, and grateful heart:-

(Morning Chronicle, 23 Oct 1793)

The Officers of the East Essex, inspired by the Duchess of Cumberland, invited Mrs. Bateman and d’Eon to Deal where “they gave a Ball; D’Eon fenced, and a purse of ten guineas was sent to her the next day.” At the parade on Sunday one of the officers presented d’Eon to the solders as a woman who had “undergone all the vicissitudes of war. “Be only, my boys,” said he, “as brave as this woman, and the Sans Culottes may land at Deal as soon as they please.”” (London Evening Post, 5-7 Nov 1793)

On the 28th of November The World reports that d’Eon and Bateman were in Canterbury visiting Lady Fielding. D’Eon had “signified her intention of making a Public Assault in every town she visits, the profits of which are to be applied towards providing flannel and other comfortable necessaries for our brave troops". However I’m not sure which other towns the two visited.

By May 1794 d’Eon was back fencing at Ranelagh, where on the 26th she faced M. Recouvrot. “Mademoiselle D’Eon appeared upon the stage, dressed in the uniform she formerly wore as Captain of Dragoons” reports the Oracle, she “fenced with as much grace and agility as if in the vigour of youth; and met her antagonist with such dexterity as to oblige him often to retreat.” (Morning Post, 26 May 1794; Oracle, 28 May 1794)

In August d’Eon and Bateman return to Brighton. Bateman “plays all the Hoydens in an excellent stile, and D’Eon fences;” reports the Morning Post “thus they manage to draw all the Company in Town.” (Morning Post, 6, 14 & 25 Aug 1794; Oracle, 13 Aug 1794)

On the 30th of August it was announced that Bateman and d’Eon were engaged to perform in Cork and Dublin. The Morning Post writes that d’Eon’s exhibitions will “be an amazing treat to the People of Ireland, as she has never been in that Kingdom.” (Morning Post, 30 Aug 1794)

On the 16th of September d’Eon was fencing in Bristol, the Morning Post reports that “she has given a challenge, which has been received, to the Fencing Master there, to fence with marked foils on that day three months.” On the 23rd she arrived in Waterford and the next day set off for Cork. (Morning Post, 19 Sept and 21 Oct, 1794; Oracle, 30 Sept 1794)

In Cork its reported that Mrs. Bateman “cast down the gauntlet to any bold Irishman, that dare come forward and push with her Quarte and Tierce. When the Curtain arose, a Drayman in the Gallery called out, “By J--- I will accept the Challenge, and will drink four quarts to her one, and lift a Tearce with her or any other Jontleman in the Theatre” (Morning Post, 27 Oct 1794)

By the 3rd of March Mrs. Bateman had returned from Ireland but “her friend d’Eon is so much indisposed as to be obliged to stop at Liverpool.” (Morning Chronicle, 3 Mar 1795)

On the 28th of May 1795 “Mrs. Bateman nearly put an end to her existence” reports the Oracle, “Not having slept for two or three nights, she imprudently took a great quantity of laudanum with spirits of salts!” The incident was reported as an accident that was “happily perceived time enough to save her life; but she still lies very ill at her house in Wimpole-street.” (Oracle 29, May 1795)

On the 10th of October 1795 the Morning Post reports that:

Madame D’Eon and Mrs. Bateman, have dissolved Partnership, and the latter sprightly Dame, now pushes Quarte and Tierce on her own account.

D’Eon also continued fencing, on the 28th of December, the Morning Post reports that d’Eon “is now performing at Bath, unaccompanied by her former friend Mrs. Bateman.”

It’s not clear why their partnership, and it seems friendship, dissolved. But it was certainly a spectacle of the stage while it lasted.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

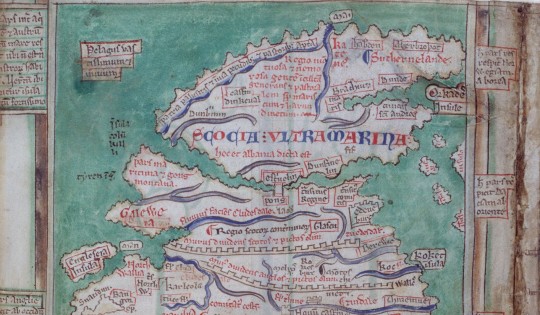

19th March 1286: “A Strong Wind Will Be Heard in Scotland”

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

On 19th March 1286, a body was discovered on a Fife beach, not far from the royal burgh of Kinghorn. The corpse was that of a 44-year-old man, and the cause of death was later diversely reported as either a broken neck or some other severe injury consistent with a fall from a horse at some point during the previous night. It is not known exactly when this body was found, nor do we know who discovered it. But we do know that the dead man was soon identified, with much dismay, as the King of Scots himself, Alexander III.

The late king had no surviving children, only a young widow who was not yet known to be pregnant, and an infant granddaughter in the kingdom of Norway. Despite this, Alexander III’s untimely death did not cause any immediate civil strife, although it did set in motion a chain of events which eventually led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. This conflict would forever alter the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and England, as well as the wider course of European history.

Although Alexander III was a moderately successful monarch, he had been unfortunate over the last ten years. His first wife, Margaret of England, had died in 1275 and Alexander initially showed no immediate interest in remarriage. At first the succession seemed secure: Margaret had left behind two sons and a daughter. However the death of the couple’s younger son David c.1281, may have prompted the king’s decision to arrange the marriages of his two surviving children over the next few years. In the summer of 1281, the twenty-year-old Princess Margaret set sail for Bergen, where she was to marry King Eirik II of Norway. Her brother Alexander, the eighteen-year-old heir to the throne, married the Count of Flanders’ daughter in November 1282. Neither marriage lasted long. The queen of Norway died in spring 1283, possibly during childbirth, while her younger brother succumbed to illness in January 1284. Within a few years, a series of unforeseen tragedies had destroyed Alexander III’s family and hopes, and the outlook for the kingdom seemed equally bleak...

All was not lost however. The king was in good health and believed he could count on the support of the realm’s leading men. Steps were swiftly taken to ensure their compliance with his plans for the succession. On 5th February 1284, a few weeks after Prince Alexander’s death, an impressive number of Scottish nobles* set their seals to an agreement at Scone. In the event of the king of Scotland’s death without any surviving legitimate children, they obliged themselves and their heirs to accept as monarch the heir at law. This was currently a baby named Margaret, the only surviving child of Alexander III’s daughter the queen of Norway.

(Drawing based on a seal belonging to Yolande of Dreux, Alexander III’s second queen. She later became Countess of Montfort and, by marriage, Duchess of Brittany. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the bishops of Scotland were to censure anyone who broke this oath, the prospect of the crown being inherited by an infant girl on the other side of the North Sea was obviously not ideal. Her grandfather struck an optimistic note in a letter to his brother-in-law Edward I of England, writing that in spite of his recent “intolerable” trials, “the child of his dearest daughter” still lived and hoping that “much good may yet be in store”. But the king would not leave everything up to chance and in October 1285, at the age of 43, he married the French noblewoman Yolande of Dreux. As the year drew to a close, Alexander might have hoped that his misfortunes were behind him. He still had his kingdom and his health, and now, with a new queen, there was every chance that he could father another son.

In fact, the king had less than six months to live. The exact circumstances of Alexander’s death are shrouded in mystery, although most sources agree on the fundamental details. Only the Chronicle of Lanercost gives a detailed account, although much cannot be corroborated, and its author had a habit of providing moral explanations for historical events. He was convinced that the calamities which befell the Scottish royal house in the 1280s were punishment for Alexander III’s personal sins. The chronicler never explicitly names these sins, but he does hint at a conflict between the king and the monks of Durham (allowing Alexander’s death to be attributed to a vengeful St Cuthbert). The chronicler also included salacious stories of Alexander’s private life, claiming:

“he used never to forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of flood or rocky cliffs, but would visit, not too creditably, matrons and nuns, virgins and widows, by day or by night as the fancy seized him, sometimes in disguise, often accompanied by a single follower.”

Although this does seem to back up the king’s habit of making reckless journeys, alone and in bad weather, the chronicle’s biases are nonetheless fairly obvious. On the other hand, the man who probably compiled the chronicle up to the year 1297 does appear to have had many contacts in Scotland. These included the confessors of the late Queen Margaret and her son Prince Alexander, as well as the latter’s tutor, the clergy of Haddington and Berwick, and the earl of Dunbar. It is unclear how he acquired information about Alexander III’s death, but the chronicle’s narrative is at least plausible and correct in its essentials. Although some of the anecdotes are a little too detailed and didactic to be entirely truthful, the narrative provides some interesting insights into contemporary behaviour, such as the way medieval Scots felt entitled to address their kings. In the absence of alternative narratives, and without necessarily subscribing to the chronicler’s moral views, it is therefore perhaps worth following Lanercost to begin with, supplementing this with additional information where possible.

(The northern half of a map of Britain, drawn by the thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris. Matthew Paris was based in the south of England and was not overly familiar with Scottish geography, but his depiction of Scotland as split over two islands and joined only at the bridge of Stirling, is nonetheless enlightening. The map is now in the public domain and has been made available by the British Libary (x))

On the evening of 18th March 1286, Alexander III is reported to have been in good spirits. This was in spite of the weather, which the author of the Chronicle of Lanercost described as being so foul, “that to me and most men, it seemed disagreeable to expose one’s face to the north wind, rain and snow”. The king of Scots was then dining at Edinburgh, attended by many of his nobles, who were preparing a response to the king of England’s ambassadors regarding the aged prisoner Thomas of Galloway. However when the court had finished dinner King Alexander was not at all anxious to retire early. Instead, not in the least deterred by the wind and rain lashing the windows, he announced his intention of spending the night with his new wife. Since Queen Yolande was then staying at Kinghorn in Fife, travelling there from Edinburgh would not only involve riding over twenty miles in the dark, but would also mean crossing the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth. Unsurprisingly, the king’s councillors tried to dissuade him. However Alexander was determined, and eventually he set off with only a few attendants, leaving his courtiers wringing their hands behind him.

The first part of the journey passed without incident and soon the king and his companions arrived at the Queen’s Ferry, by the shores of the Forth. This popular crossing point was named after Alexander’s famous ancestress St Margaret, who had established accommodation and transport for pilgrims there two hundred years earlier. But when the king himself sought passage, the ferryman pointed out that it would be very dangerous to attempt the crossing in such conditions. Alexander, undeterred, asked him if he was scared, to which the ferryman is said to have stoutly replied, “By no means, it would be a great honour to share the fate of your father’s son.” So the king and his attendants boarded the ferry and, notwithstanding the storm, the boat soon reached the shores of Fife in safety. As the king and his squires rode away from the ferry port, intending to complete the last eleven or so miles of their journey that night, they passed through the royal burgh of Inverkeithing. There, despite the evening gloom, the king’s voice was recognised by the manager of his saltpans, who was also one of the baillies of the town.** The burgess called out to the king and reprimanded him for his habit of riding abroad at night, inviting Alexander to stay with him until morning. But, laughing, Alexander dismissed his concerns and, asking only for some local serfs to act as guides, he rode off into the night.

(South Queensferry, as drawn by the eighteenth century artist John Clerk and made available for public use by the National Galleries of Scotland. Obviously the Queen’s Ferry changed a lot between the 1280s and the 1700s, but at least during this period the ferry was still the main mode of transportation across the Forth.)

By now darkness had set in and, despite the local knowledge of their guides, it was not long before every member of the king’s party became completely lost. Although they had become separated, the king’s squires eventually found the road again. However at some point they must have realised that they had a new problem: the king was nowhere to be found.

In the early fifteenth century, local tradition held that Alexander was at least heading in the right direction when he became separated from his companions. Although he too had lost sight of the main road, the king followed the shoreline, his horse carrying him swiftly over the sands towards Kinghorn. It was there, only a couple of miles from his destination, that the king’s luck finally ran out. Since there were no known witnesses to Alexander III’s death, it is unlikely that we will ever know for certain what happened that night. However most sources agree that the king’s horse probably stumbled and threw its rider. Alexander tumbled to the ground and snapped his neck and, at a stroke, the dynasty which had ruled Scotland for over two hundred years came to an end.

It is not known precisely how long the king’s body lay on the beach, alone under the moon while the waves crashed on the shore and confusion reigned among his squires and guides. However his corpse was discovered the next day and was swiftly conveyed to nearby Dunfermline. Ten days later, on 29th March 1286, the kingdom’s ruling elite gathered to see the last King Alexander buried near the high altar of the abbey kirk, in the company of his ancestors. Near the spot where the king’s body was allegedly found, a stone cross was later erected beside the road, which could still be seen by travellers over a hundred years later. The modern belief that Alexander III died when either he or his horse fell from a cliff*** (a tradition which is not supported by any mediaeval sources so far as I am aware) may stem from the position of this old cross, which possibly occupied the same spot as that of the Victorian Alexander III monument. This monument can now be seen at the side of the modern A921 road between Burntisland and Kinghorn, a permanent reminder of the role this seemingly nondescript location once played in the history of Scotland.

(The Alexander III monument near Kinghorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons- the photo was taken by Kim Traynor who has kindly made the image available for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The impact of Alexander’s death on a small mediaeval kingdom like Scotland, conditioned to look to its monarch for leadership, must have been great. Even the Lanercost chronicler admitted that the general populace was observed “bewailing his sudden death as deeply as the desolation of the realm.” However it is important not to exaggerate the scale of the crisis. Popular views of Alexander III’s death are inescapably informed by the accounts of fourteenth and fifteenth century writers, who depicted it as the root of all of Scotland’s later ills.

Writing in the aftermath of a century dominated by war, plague, famine, and climate change, it is perhaps unsurprising that many late mediaeval chroniclers looked back on Alexander III’s reign as comparatively peaceful. As the author of the fourteenth century “Gesta Annalia II” explained, “How worthy of tears and how hurtful his death was to the kingdom of Scotland is plainly shown forth by the evils of after times.” Meanwhile, in his “Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland” completed c.1420, Andrew Wyntoun portrayed Alexander’s reign as a Golden Age of peace and justice (when, just as importantly, oats only cost fourpence a boll). He incorporated an old song into his chronicle, perhaps written in the years following the king’s accident, which neatly encapsulates later views of the event and its impact:

“Quhen Alysandyr oure Kyng wes dede

That Scotland led in luẅe and lé,

Away wes sons off ale and brede,

Off wyne and wax, off gamyn and glé:

Oure gold wes changyd in to lede.

Cryste borne in to Vyrgynyté,

Succoure Scotland and remede,

That stad [is in] perplexyté.”

Wyntoun’s younger contemporary Walter Bower, author of the “Scotichronicon”, also lamented Alexander’s premature death and even rolled out a legend about Scotland’s famous seer, Thomas the Rhymer, to reinforce his point. On 18th March 1286, he claimed, the earl of Dunbar “half-jesting” asked the Rhymer for the next day’s weather forecast. True Thomas answered gloomily:

“Alas for tomorrow, a day of calamity and misery! Because before the stroke of twelve a strong wind will be heard in Scotland, the like of which has not been known since long ago. Indeed its blast will dumbfound the nations and render senseless those who hear it, it will humble what is lofty and raze what is unbending to the ground.”

The next morning came and went without any gales, so the earl decided that Thomas had gone mad- until a messenger arrived at precisely midday with news of the king’s death. Although Bower may have been attempting to bolster Thomas of Erceldoune’s reputation as a prophet (in response to English propagandic use of Merlin’s prophecies), the anecdote reveals the significance he attached to Alexander III’s death. Similarly for John Barbour, author of the fourteenth century romance “The Bruce”, there was no doubt that the story of his hero’s story began, “Quhen Alexander the king was deid / That Scotland haid to steyr and leid.” Following this, Barbour skips ahead to the selection of John Balliol as king, dismissing the six years in between as a time when the country lay “desolate”. In this way later chroniclers created the impression of an Alexandrian ‘Golden Age’ and that Scotland almost immediately descended into chaos after his death. Though understandable, these late mediaeval interpretations have traditionally hampered analysis of Alexander’s reign and the events of the decade following his death, despite the best efforts of modern historians.

(The coronation of the young Alexander III at Scone, as depicted in a manuscript version of the fifteenth century “Scotichronicon”, compiled by the Abbot of Incholm, Walter Bower. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In reality, while the king’s death was undoubtedly a deep blow, the Scottish political community rallied in the immediate aftermath. In April 1286, parliament assembled at Scone and promised to keep the peace on behalf of the rightful heir to the kingdom. Six ‘Guardians’ were to govern in the meantime- two bishops (William Fraser of St Andrews and Robert Wishart of Glasgow), two earls (Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan and Duncan, earl of Fife), and two barons (John Comyn of Badenoch and James the Steward). Despite the oaths sworn to Margaret of Norway two years earlier, there may have been some doubt as to who the “rightful heir” actually was. Certain sources claim that Alexander III’s widow Yolande of Dreux was pregnant and the political community waited anxiously for several months before the queen gave birth in November 1286. However no male heir materialised**** and by the end of the year it seems to have been generally acknowledged that the three-year-old Maid of Norway was the rightful “Lady of Scotland”. She was destined never to set foot in Scotland, but, despite her age, gender, and absence from the realm, the country did not descend into complete anarchy in the four years when she was the accepted heir to the throne. Undoubtedly there were people who had reservations about her reign: the Bruces, for example, seem to have attempted a short-lived rebellion, though the situation was soon defused by the Guardians. By 1289 the cracks were perhaps beginning to show, with the death of the earl of Buchan and the murder of the earl of Fife removing two Guardians, who were not replaced. Nonetheless, the authority of the Guardians was recognised in the absence of an adult ruler and they generally attempted to govern competently in the four years between Alexander III’s accident and the Maid of Norway’s own death in 1290.

Having received news of this second tragedy, the Guardians again acted cautiously, deciding that rival claims for the kingship should be judged in an official court chaired by a respected and powerful arbitrator. Thus they appealed to Scotland’s formidable neighbour, Edward I of England. Despite later allegations of foul play, the English king’s eventual judgement in favour of John Balliol does appear to have been consistent with the law of primogeniture and due process. It would take years of steady deterioration before war finally broke out in 1296. By then Alexander III had been dead for a decade, and though the crisis may have indirectly grown out of his demise, it was not necessarily the immediate cause of Scotland’s late mediaeval woes. Nonetheless the events of that dark night in March 1286 would leave their mark on the popular imagination for centuries, shaping Scottish history down to the present day.

(An imprint of the Great Seal used by the Guardians of Scotland following Alexander III’s death. Reproduced in the “History of Scottish seals from the eleventh to the seventeenth century”, by Walter de Gray Birch, now out of copyright and available on internet archive)

Additional Notes:

*The assembled magnates included the earls of Buchan, Dunbar, Strathearn, Atholl, Lennox, Carrick, Mar, Angus, Menteith, Ross, Sutherland, and two other earls whose titles are illegible but who may have been Caithness and Fife. The barons included Robert de Brus the elder (father of the earl of Carrick and grandfather of the future Robert I), James Stewart, John Balliol (the future king), John Comyn of Badenoch, William de Soules, Enguerrand de Coucy (Alexander III’s maternal cousin), William Murray, Reginald le Cheyne, William de St Clair, Richard Siward, William of Brechin, Nicholas de Hay, Henry de Graham, Ingelram de Balliol, Alan the son of the earl, Reginald Cheyne the younger, (John?) de Lindsay, Simon Fraser, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, Angus MacDonald, and Alan MacRuairi, among others.

** The historian G.W.S. Barrow identified this figure as Alexander the saucier the master of the royal sauce kitchen and one of the baillies of Inverkeithing.

*** There are some variations on this local tradition too- in 1794, the minister who wrote the entry for Kinghorn parish in the Old Statistical Account claimed that the ‘King’s Wood-end’ near the site of the current Alexander III monument was where the king liked to hunt and that he fell from his horse while on a hunting trip.

****The Guardians and other nobles may have assembled at Clackmannan for the birth. Several modern historians have accepted Walter Bower’s statement that the queen’s baby was stillborn, despite the Chronicle of Lanercost’s somewhat fantastic tale of a fake pregnancy, with Yolande being caught conspiring to smuggle an actor’s son into Stirling Castle.

Selected Bibliography:

- “The Chronicle of Lanercost”, as translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, Volume 2, ed. Joseph Bain

- Rymer’s “Foedera…”, Volume 1 part 1

- “Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland”, vol 1., ed. Joseph Stevenson

- “Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson (especially Annals of Worcester; Thomas Wykes; Chronicles in Annales Monastici)

- “Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson (esp. Chronicle of Holyrood, various continuations of the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland; John of Evenden; Nicholas Trivet)

- “The Flowers of History… as Collected by Mathew of Westminster”, ed. C.D. Yonge - Gesta Annalia II (formerly attributed to John of Fordun) in “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W. F. Skene

- John Barbour’s “The Brus”, ed. A.A.M. Duncan

- “The Orygynale Cronikil of the Scotland”, vol.2., by Andrew Wyntoun, ed. David Laing

- “A History Book for Scots: Selections from the Scotichronicon”, ed. D.E.R. Watt

- “The Authorship of the Lanercost Chronicle”, by A.G. Little in the English Historical Review, vol. 31 no. 122, p. 269-279

- “The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

- “Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland”, G.W.S. Barrow

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1230-1371”, Michael Brown

I have extensive notes so if anyone needs a reference for a specific detail please let me know.

#Scottish history#British history#Scotland#thirteenth century#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#1280s#Alexander III#Yolande of Dreux#House of Canmore#Margaret of England#Margaret Maid of Norway#Margaret of Scotland Queen of Norway#Prince Alexander (d.1284)#Edward I of England#William Fraser Bishop of St Andrews#Robert Wishart Bishop of Glasgow#John Comyn of Badenoch#Alexander Comyn Earl of Buchan#James the Steward#Duncan Earl of Fife (d.1288)#Chronicle of Lanercost#Patrick III Earl of Dunbar#Walter Bower#Scotichronicon#Andrew Wyntoun#John Barbour#John of Fordun#Gesta Annalia II#Sources

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

What the heck was this blue 'luminous event' photographed from the space station?

https://sciencespies.com/space/what-the-heck-was-this-blue-luminous-event-photographed-from-the-space-station/

What the heck was this blue 'luminous event' photographed from the space station?

On October 8, French astronaut Thomas Pesquet captured something strikingly rare from on board the International Space Station (ISS).

The photo – which is a single frame taken from a longer timelapse – might look like it shows a cobalt bomb exploding over Europe, but this scary-looking blue light didn’t do any damage. In fact, most people would never have noticed it happening.

Instead, the frame shows something far less ominous called a ‘transient luminous event‘ – a lightning-like phenomenon striking upwards in the upper atmosphere.

Also known as upper-atmospheric lighting, transient luminous events are a bunch of related phenomena which occur during thunderstorms, but significantly above where normal lighting would appear. While related to lighting, they work a little bit differently.

There are ‘blue jets’, which happen lower down in the stratosphere, triggered by lightning. If the lighting propagates through the negatively charged (top) region of the thunderstorm clouds before it gets through the positive region below, the lightning ends up striking upwards, igniting a blue glow from molecular nitrogen.

Then there are red SPRITES (Stratospheric/mesospheric Perturbations Resulting from Intense Thunderstorm Electrification) – electrical discharges that often glow red, occurring high above a thunderstorm cell, triggered by disturbances from the lightning below – and slightly dimmer red ELVES (Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources) in the ionosphere.

Sticking with the theme, there are also TROLLs (Transient Red Optical Luminous Lineaments) which occur after strong SPRITES, as well as Pixies and GHOSTS. We’re sure the scientists had lots of fun naming all of these phenomena.

“What is fascinating about this lightning is that just a few decades ago they had been observed anecdotally by pilots, and scientists were not convinced they actually existed,” Pesquet explains in a photo caption.

“Fast forward a few years and we can confirm elves, and sprites are very real and could be influencing our climate too!”

Although Pesquet doesn’t explain specifically which type of luminous event we’re seeing, this particular image could be showing a ‘blue starter’, which is a blue jet that doesn’t quite make it to the jet part, and instead creates a shorter and brighter glow.

These events are particularly hard to photograph from the ground as they are both very high in the sky and also regularly obscured by storm clouds. Plus, the phenomena usually only last for milliseconds or a couple of seconds each time.

With all those things in mind, it makes the ISS a particularly great place to look for these transient events, particularly if you have a timelapse turned on. So far we’ve seen a number of these events captured by astronauts on the ISS, and a small number taken from the ground.

Interestingly, Earth isn’t even the only place where the light shows take place, with researchers discovering just last year that ‘blue sprites’ were occurring on Jupiter too.

“The Space Station is extremely well suited for this observatory as it flies over the equator where there are more thunderstorms,” says Pesquet.

“This is a very rare occurrence and we have a facility outside Europe’s Columbus laboratory dedicated to observing these flashes of light.”

We hope that this research will give us plenty more photos of this incredible phenomena in the future!

#Space

1 note

·

View note

Text

subfluences, of

ploughs expansive sheets of flame, subfluence of the beaming sconce! — limely waving 1 useful for reference, subfluence of whom the exquisite portrait, join the following list 2 subfluence of loss 3 long under the in when mixture containing organic subfluence of 4 I’d like to know the subfluence of the fairies differences of opinion about in employment of the word 5 enterprise, and subfluence of 6 conversation to another subfluence of 7 distance as to be entirely out of the ínspire of the long wire this arrangement is subfluence of 8 subfluence of chlorómethy ! and 9 if not subfluence of slavery 10 Pages could be written upon the subfluence of water, its importance waters 11 subfluence of a large proportion of the lands 12 Therapeutical subfluence of 13 temptation to be subfluence of 14 an answer. The cause was subfluence of 15 sum and subfluence and suggestion of 16 What processes here occur, accompanying reactions take place and the and which take place especially under the in-intensity of attraction which these other subfluence of light 17 the in of books on the ever-expanding subfluence of the far 18 subfluence of a periscope 19 subfluence of style was distinctly jagged pseudo-geometrical slack 20 the azoted subfluence of 21 subfluence of “Some English and Old French forms a volume of Phrases” 22 subfluence of those decisions 23 subfluence of rays 24

sources (all OCR cross-column misreads/confusions)

1 ex The Universal Magazine v.14 (1754) : 6 preview snippet, evidently from “A descant upon creation” by James Hervey (1714-58 *), found at his Meditations and Contemplations. In Two Volumes... (London, 1796) : 151 2 ex “Biographical Particulars of Celebrated Persons Lately Deceased,” here involving The Rev. Mark Noble and John Fleming, late Lord de Tabley, in The New Monthly 21 (August 1, 1827) : 350 3 ex E. Bellchambers, A General Biographical Dictionary : Containing Lives of the most emininent persons of all ages and nations. Vol. 4 (of 4; London, 1835) : 252 involving entries for Conrad Vorstius (“an eminent divine”; 1569-1622) and Gerard John Vossius (poet, philologist, professor of rhetoric and chronology; 1577-1649) 4 entry for “toxicology” by James Apjohn (1796-1886 *), in The Cyclopaedia of Practical Medicine Vol. 4 (SOF — YAW) Supplement (London, 1835) : 189-243 (214) 5 ex T. F., “Familiar Epistles from Ireland, Letter the Fourth, from Terence Flynn, Esq. to Dennis Moriarty, Student-at-Law, London.” in Fraser’s Magazine 42 (September 1850) : 319-328 (327) 6 ex Archibald Alison, History of Europe from the Commencement of the French Revolution in 1789 to the Restoration of the Bourbons in 1815. Ninth edition, vol. 12 (Edinburgh and London, 1855) : 50 7 ex John Flesher, ed., Arvine’s Cyclopaedia of Moral and Religious Anecdotes : A collection of nearly three thousand facts, incidents, narratives, examples, and testimonies... the whole arranged and classified on a new plan, with copious topical and scriptural indexes. (London, 1859) : 23 a later edition and who was Arvine? *Kazlitt Arvine, name originally Silas Wheelock Palmer, changed by Mass. leg. while at Newton, b. Centerville, N.Y., Dec. 18, 1819. Wes. U. 1841; N.T.I. 1842-45; ord. Nov. 6, 1845; p. Woonsocket, R.I., 1845-47; Providence ch., New York, N.Y., 1847-49; West Boylston, Mass., 1849-51; author, Cyclopedia of Moral and Religious Anecdote, 1848; a volume of poems; sermons; d. Worcester, July 15, 1851. ex The Newton Theological Institution, General Catalogue, Eleventh Edition (Newton Centre Massachusetts, April 1912) : 56 8 ex entry (by Joseph Henry, of the Smithsonian Institution) for “Magneto-Electricity” in George Ripley and Charles A. Dana, eds., The New American Cyclopaedia : A popular dictionary of general knowledge, Vol. 11 (MacGillvray-Moxa). (New York, 1861) : 67-72 (69) 9 ex letter to the editor on the topic of Bichloride of Methylene (from A. Russell Strachan), in The Medical record : a semi-monthly journal of medicine and surgery (March 2, 1868) : 22 on mixture of alcohol, chloroform and ether, see wikipedia 10 ex “Slavery,” in The Complete Works of W(illiam). E(llery). Channing: With an Introduction (London, 1870?) : 570-615 (591) on Channing (1780-1842), consult wikipedia 11 ex Charles McIntire, Jr., “Science in Common Things,” in Our Home: A Monthly Magazine (Devoted to Local and General Literature) 1:6 (Somerville, N.J.; June 1873) : 247-250 12 ex History of Summit County : With an Outline Sketch of Ohio. Edited by William Henry Perrin. Illustrated. (Chicago, 1881) : 280 13 ex Edwin J. Houston. A Dictionary of Electrical Words, Terms and Phrases, second edition, rewritten and greatly enlarged. (New York, 1892) : 200 14 ex John Brooks Leavitt. “On the Administration of Justice,” in The Counsellor : The New York Law School Law Journal 2:4 (January 1893) : 101-108 15 ex Birmingham Mineral R. Co. v. City of Bessemer (Supreme Court of Alabama. July 27, 1893), in The Southern Reporter 13 (June 14 – December 20, 1893) : 487-489 16 ex Josephine Lazarus, “Jewish Thought in Modern English Poetry : Robert Browning” in The Menorah (“official organ of the Jewish Chautauqua”) 38:1 (January 1905) : 42-53 (44) 17 snippet view only, ex Society of Dyers and Colourists, Bradford, Eng. (Yorkshire), The Journal 25 (1909) : 12 18 ex review of Joseph H. Longford, The Story of Old Japan, in The Oriental Review 1:11 (New York; April 10, 1911) : 212-213 19 ex “The Story of the Week” (involving Canadian War Graft, and The “Sussex” Question), The Independent vol 86 (April 17, 1916) : 96-99 20 ex The American Magazine of Art 8:3 (January 1917) : 118 involving “A fiction among futurists” and an obituary for Henry W. Ranger (landscape painter) 21 ex Andre Dubosc, “Application of Catalysis to Vulcanization,” in The Rubber Age 3:2 (April 25, 1918) : 78-79 22 ex XXIX. Literature and Language / Romance Languages and Literature, by George L. Hamilton, in The American Year Book : A Record of Events and Progress, 1918. Edited by Francis G. Wickware... with coöperation of a supervisory board representing national learned societies (New York, 1919) : 778 23 ex Thomas v. Little et al. (June 7, 1923) in Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Alabama Vol. 209 (1923) : 590-592 24 snippet view, ex International Labour Office, Occupation and Health: Encyclopedia of Hygiene, Pathology, and Social Welfare 2 (1934) : 417

—

2 of n

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utopia and Apocalypse: Pynchon’s Populist/Fatalist Cinema

The rhythmic clapping resonates inside these walls, which are hard and glossy as coal: Come-on! Start-the-show! Come-on! Start-the-show! The screen is a dim page spread before us, white and silent. The film has broken, or a projector bulb has burned out. It was difficult even for us, old fans who’ve always been at the movies (haven’t we?) to tell which before the darkness swept in.

--from the last page of Gravity’s Rainbow

To begin with a personal anecdote: Writing my first book (to be published) in the late 1970s, an experimental autobiography titled Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (Harper & Row, 1980), published in French as Mouvements: Une vie au cinéma (P.O.L, 2003), I wanted to include four texts by other authors—two short stories (“In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” by Delmore Schwartz, “The Secret Integration” by Thomas Pynchon) and two essays (“The Carole Lombard in Macy’s Window” by Charles Eckert, “My Life With Kong” by Elliott Stein)—but was prevented from doing so by my editor, who argued that because the book was mine, texts by other authors didn’t belong there. My motives were both pluralistic and populist: a desire both to respect fiction and non-fiction as equal creative partners and to insist that the book was about more than just myself and my own life. Because my book was largely about the creative roles played by the fictions of cinema on the non-fictions of personal lives, the anti-elitist nature of cinema played a crucial part in these transactions.`

In the case of Pynchon’s 1964 story—which twenty years later, in his collection Slow Learner, he would admit was the only early story of his that he still liked—the cinematic relevance to Moving Places could be found in a single fleeting but resonant detail: the momentary bonding of a little white boy named Tim Santora with a black, homeless, alcoholic jazz musician named Carl McAfee in a hotel room when they discover that they’ve both seen Blood Alley (1955), an anticommunist action-adventure with John Wayne and Lauren Bacall, directed by William Wellman. Pynchon mentions only the film’s title, but the complex synergy of this passing moment of mutual recognition between two of its dissimilar viewers represented for me an epiphany, in part because of the irony of such casual camaraderie occurring in relation to a routine example of Manichean Cold War mythology. Moreover, as a right-wing cinematic touchstone, Blood Alley is dialectically complemented in the same story by Tim and his friends categorizing their rebellious schoolboy pranks as Operation Spartacus, inspired by the left-wing Spartacus (1960) of Kirk Douglas, Dalton Trumbo, and Stanley Kubrick.

For better and for worse, all of Pynchon’s fiction partakes of this populism by customarily defining cinema as the cultural air that everyone breathes, or at least the river in which everyone swims and bathes. This is equally apparent in the only Pynchon novel that qualifies as hackwork, Inherent Vice (2009), and the fact that Paul Thomas Anderson’s adaptation of it is also his worst film to date—a hippie remake of Chinatown in the same way that the novel is a hippie remake of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald—seems logical insofar as it seems to have been written with an eye towards selling the screen rights. As Geoffrey O’Brien observed (while defending this indefensible book and film) in the New York Review of Books (January 3, 2015), “Perhaps the novel really was crying out for such a cinematic transformation, for in its pages people watch movies, remember them, compare events in the ‘real world’ to their plots, re-experience their soundtracks as auditory hallucinations, even work their technical components (the lighting style of cinematographer James Wong Howe, for instance) into aspects of complex conspiratorial schemes.” (Despite a few glancing virtues, such as Josh Brolin’s Nixonesque performance as "Bigfoot" Bjornsen, Anderson’s film seems just as cynical as its source and infused with the same sort of misplaced would-be nostalgia for the counterculture of the late 60s and early 70s, pitched to a generation that didn’t experience it, as Bertolucci’s Innocents: The Dreamers.)

From The Crying of Lot 49’s evocation of an orgasm in cinematic terms (“She awoke at last to find herself getting laid; she’d come in on a sexual crescendo in progress, like a cut to a scene where the camera’s already moving”) to the magical-surreal guest star appearance of Mickey Rooney in wartime Europe in Gravity’s Rainbow, cinema is invariably a form of lingua franca in Pynchon’s fiction, an expedient form of shorthand, calling up common experiences that seem light years away from the sectarianism of the politique des auteurs. This explains why his novels set in mid-20th century, such as the two just cited, when cinema was still a common currency cutting across classes, age groups, and diverse levels of education, tend to have the greatest number of movie references. In Gravity’s Rainbow—set mostly in war-torn Europe, with a few flashbacks to the east coast U.S. and flash-forwards to the contemporary west coast—this even includes such anachronistic pop ephemera as the 1949 serial King of the Rocket Men and the 1955 Western The Return of Jack Slade (which a character named Waxwing Blodgett is said to have seen at U.S. Army bases during World War 2 no less than twenty-seven times), along with various comic books.

Significantly, “The Secret Integration”, a title evoking both conspiracy and countercultural utopia, is set in the same cozy suburban neighborhood in the Berkshires from which Tyrone Slothrop, the wartime hero or antihero of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), aka “Rocketman,” springs, with his kid brother and father among the story’s characters. It’s also the same region where Pynchon himself grew up. And Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s magnum opus and richest work, is by all measures the most film-drenched of his novels in its design as well as its details—so much so that even its blocks of text are separated typographically by what resemble sprocket holes. Unlike, say, Vineland (1990), where cinema figures mostly in terms of imaginary TV reruns (e.g., Woody Allen in Young Kissinger) and diverse cultural appropriations (e.g., a Noir Center shopping mall), or the post-cinematic adventures in cyberspace found in the noirish (and far superior) east-coast companion volume to Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge (2013), cinema in Gravity’s Rainbow is basically a theatrical event with a social impact, where Fritz Lang’s invention of the rocket countdown as a suspense device (in the 1929 Frau im mond) and the separate “frames” of a rocket’s trajectory are equally relevant and operative factors. There are also passing references to Lang’s Der müde Tod, Die Nibelungen, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, and Metropolis—not to mention De Mille’s Cleopatra, Dumbo, Freaks, Son of Frankenstein, White Zombie, at least two Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals, Pabst, and Lubitsch—and the epigraphs introducing the novel’s second and third sections (“You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood — Merian C. Cooper to Fay Wray” and “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas any more…. –Dorothy, arriving in Oz”) are equally steeped in familiar movie mythology.

These are all populist allusions, yet the bane of populism as a rightwing curse is another near-constant in Pynchon’s work. The same ambivalence can be felt in the novel’s last two words, “Now everybody—“, at once frightening and comforting in its immediacy and universality. With the possible exception of Mason & Dixon (1997), every Pynchon novel over the past three decades—Vineland, Against the Day (2006), Inherent Vice, and Bleeding Edge—has an attractive, prominent, and sympathetic female character betraying or at least acting against her leftist roots and/or principles by being first drawn erotically towards and then being seduced by a fascistic male. In Bleeding Edge, this even happens to the novel’s earthy protagonist, the middle-aged detective Maxine Tarnow. Given the teasing amount of autobiographical concealment and revelation Pynchon carries on with his public while rigorously avoiding the press, it is tempting to see this recurring theme as a personal obsession grounded in some private psychic wound, and one that points to sadder-but-wiser challenges brought by Pynchon to his own populism, eventually reflecting a certain cynicism about human behavior. It also calls to mind some of the reflections of Luc Moullet (in “Sainte Janet,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 86, août 1958) aroused by Howard Hughes’ and Josef von Sternberg’s Jet Pilot and (more incidentally) by Ayn Rand’s and King Vidor’s The Fountainhead whereby “erotic verve” is tied to a contempt for collectivity—implicitly suggesting that rightwing art may be sexier than leftwing art, especially if the sexual delirium in question has some of the adolescent energy found in, for example, Hughes, Sternberg, Rand, Vidor, Kubrick, Tashlin, Jerry Lewis, and, yes, Pynchon.

One of the most impressive things about Pynchon’s fiction is the way in which it often represents the narrative shapes of individual novels in explicit visual terms. V, his first novel, has two heroes and narrative lines that converge at the bottom point of a V; Gravity’s Rainbow, his second—a V2 in more ways than one—unfolds across an epic skyscape like a rocket’s (linear) ascent and its (scattered) descent; Vineland offers a narrative tangle of lives to rhyme with its crisscrossing vines, and the curving ampersand in the middle of Mason & Dixon suggests another form of digressive tangle between its two male leads; Against the Day, which opens with a balloon flight, seems to follow the curving shape and rotation of the planet.

This compulsive patterning suggests that the sprocket-hole design in Gravity’s Rainbow’s section breaks is more than just a decorative detail. The recurrence of sprockets and film frames carries metaphorical resonance in the novel’s action, so that Franz Pökler, a German rocket engineer allowed by his superiors to see his long-lost daughter (whom he calls his “movie child” because she was conceived the night he and her mother saw a porn film) only once a year, at a children’s village called Zwölfkinder, and can’t even be sure if it’s the same girl each time:

So it has gone for the six years since. A daughter a year, each one about a year older, each time taking up nearly from scratch. The only continuity has been her name, and Zwölfkinder, and Pökler’s love—love something like the persistence of vision, for They have used it to create for him the moving image of a daughter, flashing him only these summertime frames of her, leaving it to him to build the illusion of a single child—what would the time scale matter, a 24th of a second or a year (no more, the engineer thought, than in a wind tunnel, or an oscillograph whose turning drum you can speed or slow at will…)?

***

Cinema, in short, is both delightful and sinister—a utopian dream and an apocalyptic nightmare, a stark juxtaposition reflected in the abrupt shift in the earlier Pynchon passage quoted at the beginning of this essay from present tense to past tense, and from third person to first person. Much the same could be said about the various displacements experienced while moving from the positive to the negative consequences of populism.

Pynchon’s allegiance to the irreverent vulgarity of kazoos sounding like farts and concomitant Spike Jones parodies seems wholly in keeping with his disdain for David Raksin and Johnny Mercer’s popular song “Laura” and what he perceives as the snobbish elitism of the Preminger film it derives from, as expressed in his passionate liner notes to the CD compilation “Spiked!: The Music of Spike Jones” a half-century later:

The song had been featured in the 1945 movie of the same name, supposed to evoke the hotsy-totsy social life where all these sophisticated New York City folks had time for faces in the misty light and so forth, not to mention expensive outfits, fancy interiors,witty repartee—a world of pseudos as inviting to…class hostility as fish in a barrel, including a presumed audience fatally unhip enough to still believe in the old prewar fantasies, though surely it was already too late for that, Tin Pan Alley wisdom about life had not stood a chance under the realities of global war, too many people by then knew better.

Consequently, neither art cinema nor auteur cinema figures much in Pynchon’s otherwise hefty lexicon of film culture, aside from a jokey mention of a Bengt Ekerot/Maria Casares Film Festival (actors playing Death in The Seventh Seal and Orphée) held in Los Angeles—and significantly, even the “underground”, 16-millimeter radical political filmmaking in northern California charted in Vineland becomes emblematic of the perceived failure of the 60s counterculture as a whole. This also helps to account for why the paranoia and solipsism found in Jacques Rivette’s Paris nous appartient and Out 1, perhaps the closest equivalents to Pynchon’s own notions of mass conspiracy juxtaposed with solitary despair, are never mentioned in his writing, and the films that are referenced belong almost exclusively to the commercial mainstream, unlike the examples of painting, music, and literature, such as the surrealist painting of Remedios Varo described in detail at the beginning of The Crying of Lot 49, the importance of Ornette Coleman in V and Anton Webern in Gravity’s Rainbow, or the visible impact of both Jorge Luis Borges and William S. Burroughs on the latter novel. (1) And much of the novel’s supply of movie folklore—e.g., the fatal ambushing of John Dillinger while leaving Chicago’s Biograph theater--is mainstream as well.

Nevertheless, one can find a fairly precise philosophical and metaphysical description of these aforementioned Rivette films in Gravity’s Rainbow: “If there is something comforting -- religious, if you want — about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” And the white, empty movie screen that appears apocalyptically on the novel’s final page—as white and as blank as the fusion of all the colors in a rainbow—also appears in Rivette’s first feature when a 16-millimeter print of Lang’s Metropolis breaks during the projection of the Tower of Babel sequence.

Is such a physically and metaphysically similar affective climax of a halted film projection foretelling an apocalypse a mere coincidence? It’s impossible to know whether Pynchon might have seen Paris nous appartient during its brief New York run in the early 60s. But even if he hadn’t (or still hasn’t), a bitter sense of betrayed utopian possibilities in that film, in Out 1, and in most of his fiction is hard to overlook. Old fans who’ve always been at the movies (haven’t we?) don’t like to be woken from their dreams.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Footnote

For this reason, among others, I’m skeptical about accepting the hypothesis of the otherwise reliable Pynchon critic Richard Poirier that Gravity’s Rainbow’s enigmatic references to “the Kenosha Kid” might allude to Orson Welles, who was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Steven C. Weisenburger, in A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion (Athens/London: The University of Georgia Press, 2006), reports more plausibly that “the Kenosha Kid” was a pulp magazine character created by Forbes Parkhill in Western stories published from the 1920s through the 1940s. Once again, Pynchon’s populism trumps—i.e. exceeds—his cinephilia.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

185 RARE BOOKS ON WITCHCRAFT, GHOSTS, OCCULT, DEMON, HYPNOTISM, ASTROLOGY ON DVD