Text

Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist Dancing Costumes

Photos scanned from a 2011 Vajrayana Buddhism Dancing Costume catalogue. © Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer, and Kashba. See rest of catalogue on their website here.

The costumes blend elements from Tibetan, Mongolian, and Nepalese cultures. They may also be used for shamanistic and/or tantric rituals.

#tibet#nepal#mongolia#china#buddhism#vajrayana buddhism#shamanism#tantric buddhism#asia#asian culture#asian art#dancing costume#folk dance#culture

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

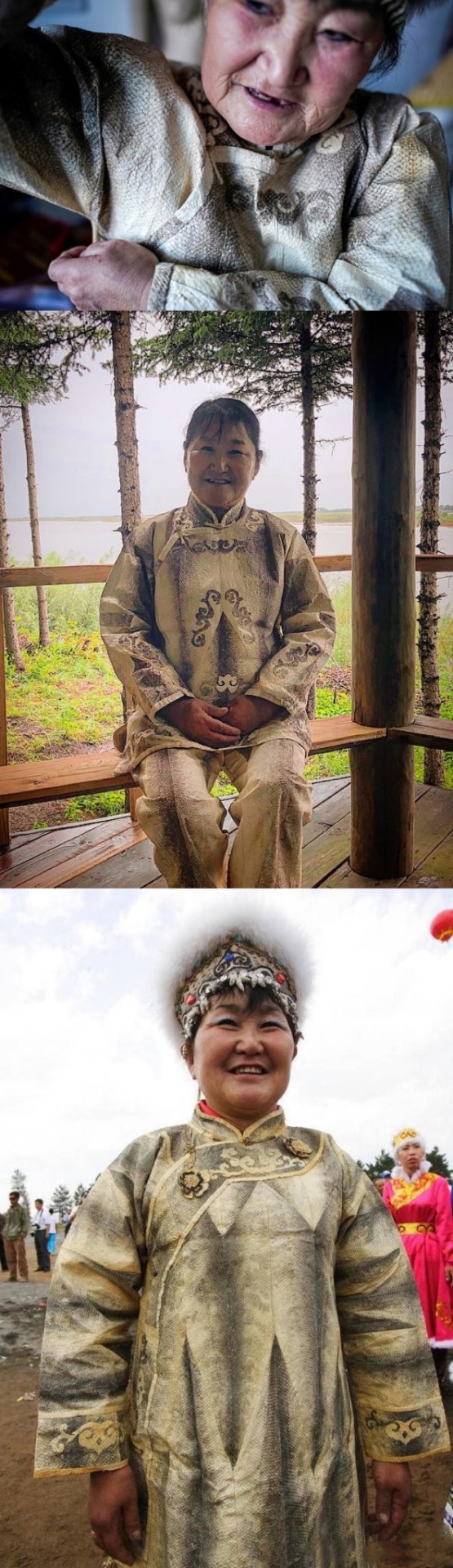

Fishskin Robes of the Ethnic Tungusic People of China and Russia

Oroch woman’s festive robe made of fish skin, leather, and decorative fur trimmings [image source].

Nivkh woman’s fish-skin festival coats (hukht), late 19th century. Cloth: fish skin, sinew (reindeer), cotton thread; appliqué and embroidery. Promised gift of Thomas Murray L2019.66.2, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, United States [image source].

Back view of a Nivkh woman’s robe [image source].

Front view of a Nivkh woman’s robe [image source].

Women’s clothing, collected from a Nivkh community in 1871, now in the National Museum of Denmark. Photo by Roberto Fortuna, courtesy Wikimedia Commons [image source].

The Hezhe people 赫哲族 (also known as Nanai 那乃) are one of the smallest recognized minority groups in China composed of around five thousand members. Most live in the Amur Basin, more specifically, around the Heilong 黑龙, Songhua 松花, and Wusuli 乌苏里 rivers. Their wet environment and diet, composed of almost exclusively fish, led them to develop impermeable clothing made out of fish skin. Since they are part of the Tungusic family, their clothing bears resemblance to that of other Tungusic people, including the Jurchen and Manchu.

They were nearly wiped out during the Imperial Japanese invasion of China but, slowly, their numbers have begun to recover. Due to mixing with other ethnic groups who introduced the Hezhen to cloth, the tradition of fish skin clothing is endangered but there are attempts of preserving this heritage.

Hezhen woman stitching together fish skins [image source].

Top to bottom left: You Wenfeng, 68, an ethnic Hezhen woman, poses with her fishskin clothes at her studio in Tongjiang, Heilongjiang province, China December 31, 2019. Picture taken December 31, 2019 by Aly Song for Reuters [image source].

Hezhen Fish skin craft workshop with Mrs. You Wen Fen in Tongjian, China. © Elisa Palomino and Joseph Boon [image source].

Hezhen woman showcasing her fishskin outfit [image source].

Hezhen fish skin jacket and pants, Hielongiang, China, mid 20th century. In the latter part of the 20th century only one or two families could still produce clothing like this made of joined pieces of fish skin, which makes even the later pieces extremely rare [image source].

Detail view of the stitching and material of a Hezhen fishskin jacket in the shape of a 大襟衣 dajinyi or dajin, contemporary. Ethnic Costume Museum of Beijing, China [image source].

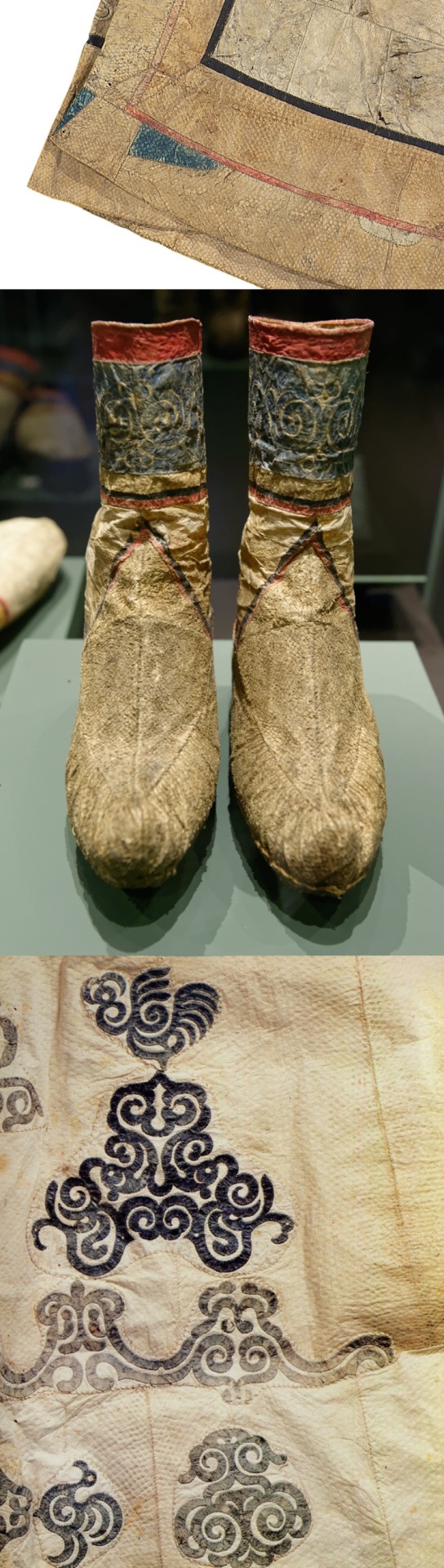

Hezhen fishskin boots, contemporary. Ethnic Costume Museum of Beijing, China [image source].

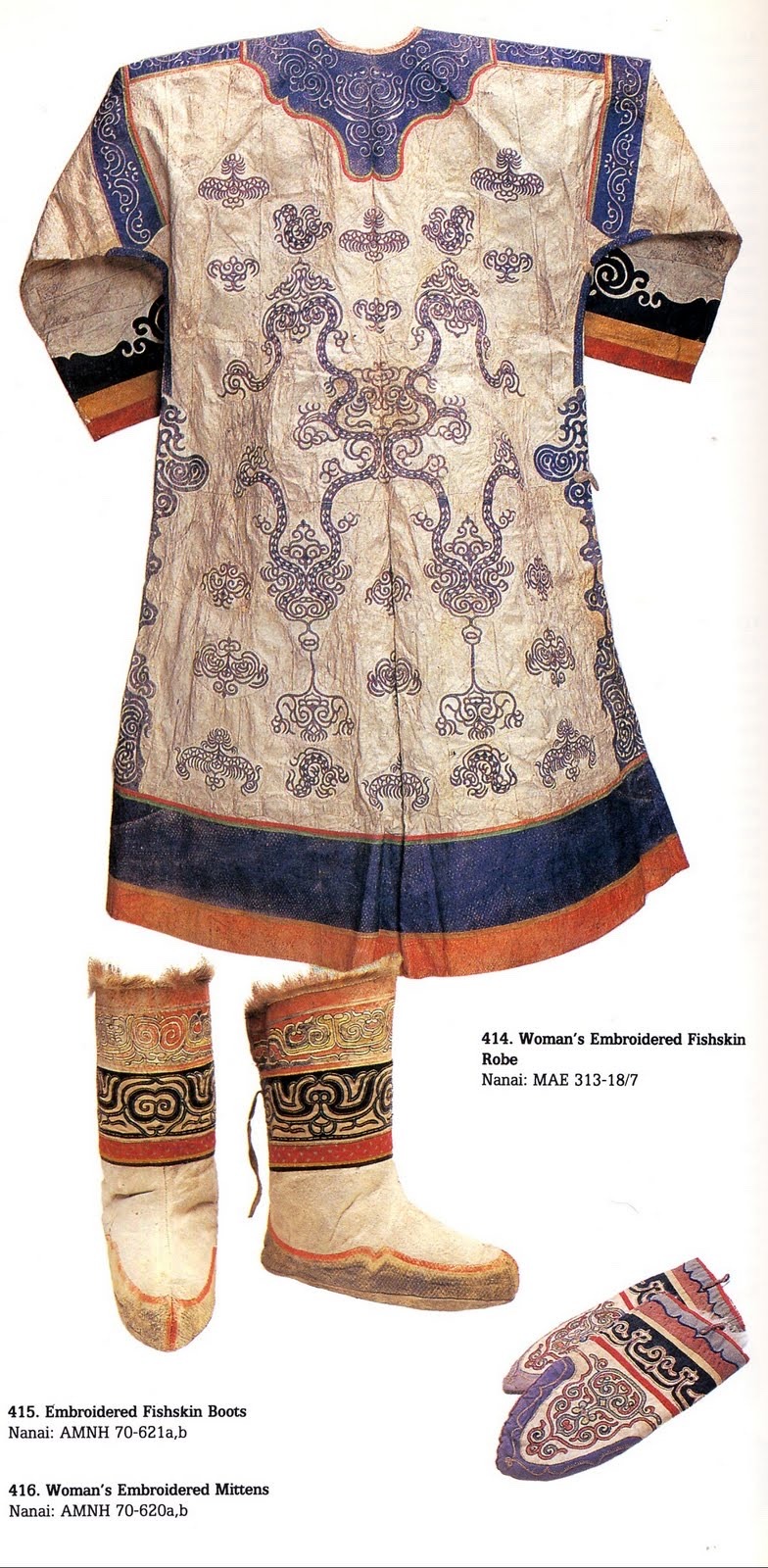

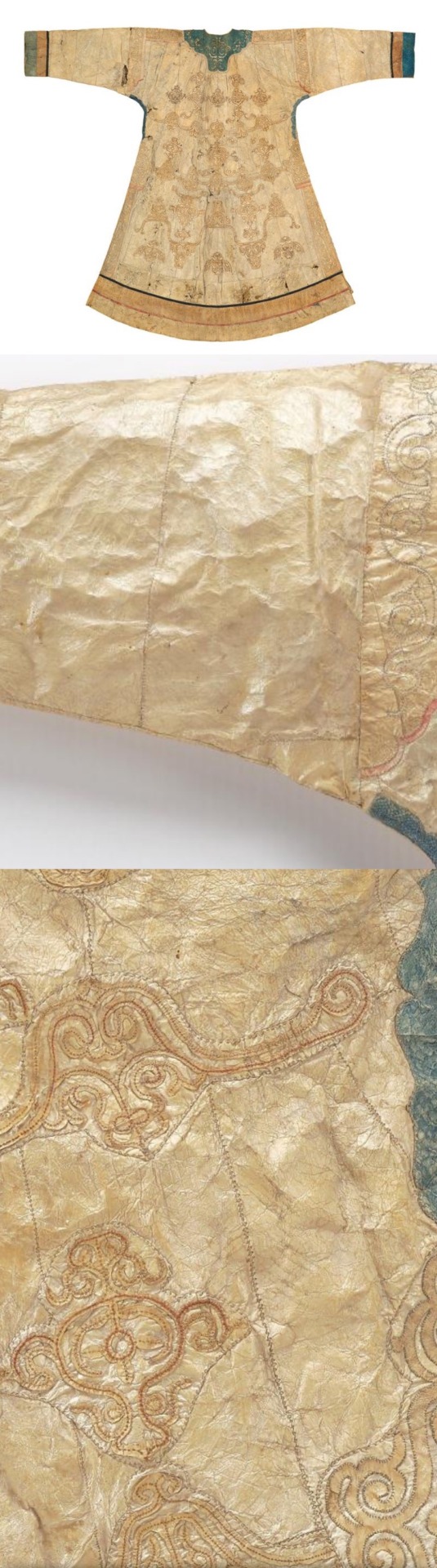

Although Hezhen clothing is characterized by its practicality and ease of movement, it does not mean it’s devoid of complexity. Below are two examples of ornate female Hezhen fishskin robes. Although they may look like leather or cloth at first sight, they’re fully made of different fish skins stitched together. It shows an impressive technical command of the medium.

赫哲族鱼皮长袍 [Hezhen fishskin robe]. Taken July 13, 2017. © Huanokinhejo / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 [image source].

Image containing a set of Hezhen clothes including a woman’s fishskin robe [image source].

The Nivkh people of China and Russia also make clothing out of fish skin. Like the Hezhen, they also live in the Amur Basin but they are more concentrated on and nearby to Sakhalin Island in East Siberia.

Top to bottom left: Woman’s fish-skin festival coat (hukht) with detail views. Unknown Nivkh makers, late 19th century. Cloth: fish skin, sinew (reindeer), cotton thread; appliqué and embroidery. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the Mary Griggs Burke Endowment Fund; purchase from the Thomas Murray Collection 2019.20.31 [image source].

Top to bottom right: detail view of the lower hem of the robe to the left after cleaning [image source].

Nivkh or Nanai fish skin boots from the collection of Musée du quai Branly -Jacques Chirac. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 [image source].

Detail view of the patterns at the back of a Hezhen robe [image source].

Read more:

#china#russia#tungusic#hezhe#nanai#fishskin#ethnic minorities#nivkh#chinese culture#history#russian culture#amur basin#heilongjiang#east siberia#ethnic clothing

974 notes

·

View notes

Text

Origins of the Pibo: Let’s take a trip along the Silk Road.

1. Introduction to the garment:

Pibo 披帛 refers to a very thin and long shawl worn by women in ancient East Asia approximately between the 5th to 13th centuries CE. Pibo is a modern name and its historical counterpart was pei 帔. But I’ll use pibo as to not confuse it with Ming dynasty’s xiapei 霞帔 and a much shorter shawl worn in ancient times also called pei.

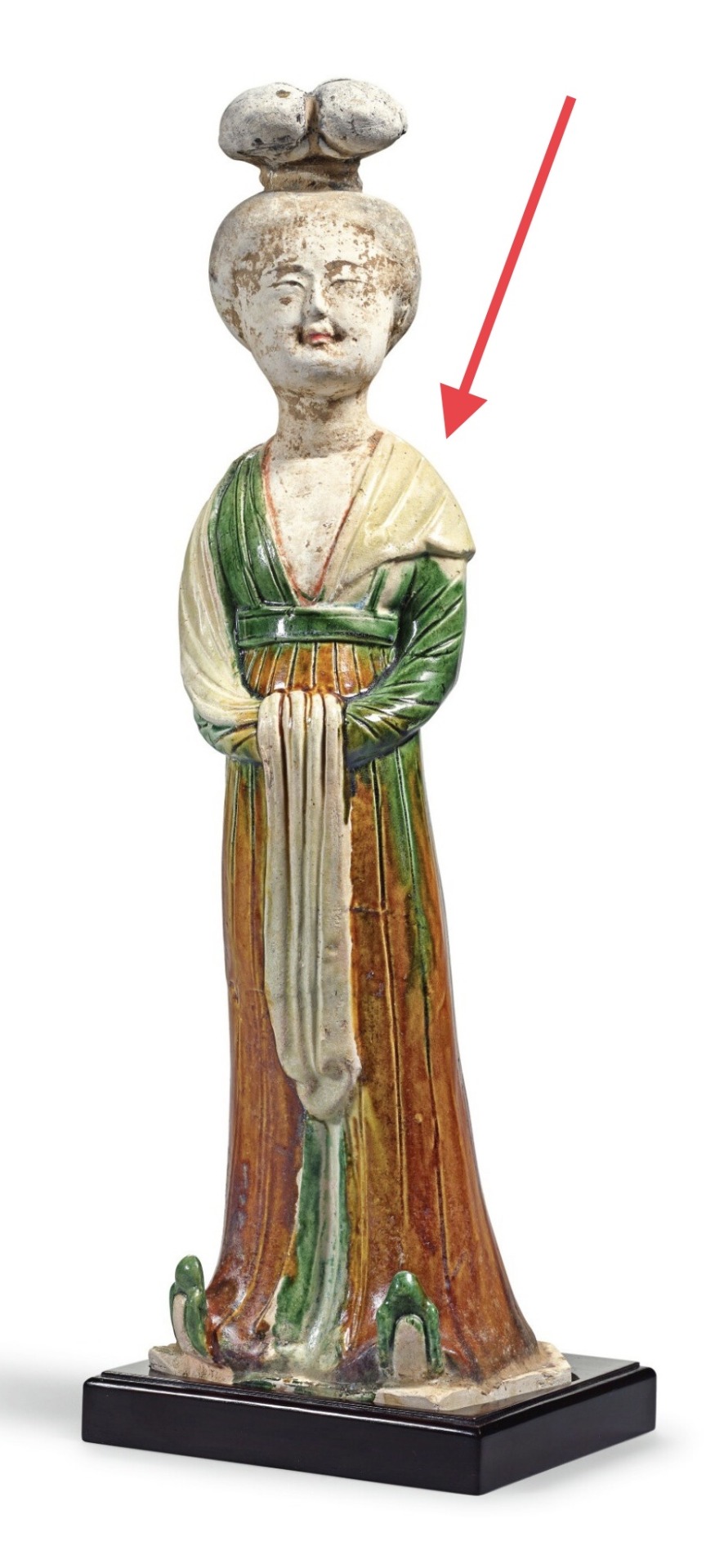

Below is a ceramic representation of the popular pibo.

A sancai-glazed figure of a court lady, Tang Dynasty (618–690, 705–907 CE) from the Sze Yuan Tang Collection. Artist unknown. Sotheby’s [image source].

Although some internet sources claim that pibo in China can be traced as far back as the Qin (221-206 BCE) or Han (202 BCE–9 CE; 25–220 CE) dynasties, we don’t start seeing it be depicted as we know it today until the Northern and Southern dynasties period (420-589 CE). This has led to scholars placing pibo’s introduction to East Asia until after Buddhism was introduced in China. Despite the earliest art representations of the long scarf-like shawl coming from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, the pibo reached its popularity apex in the Tang Dynasty (618–690 CE: 705–907 CE).

Academic consensus: Introduction via the Silk Road.

The definitive academic consensus is that pibo evolved from the dajin 搭巾 (a long and thin scarf) worn by Buddhist icons introduced to China via the Silk Road from West Asia.

披帛是通过丝绸之路传入中国的西亚文化, 与中国服饰发展的内因相结合而流行开来的一种"时世妆" 的形式. 沿丝绸之路所发现的披帛, 反映了丝绸贸易的活跃.

[Trans] Pibo (a long piece of cloth covering the back of the shoulders) was a popular female fashion period accessory introduced to China by West Asian cultures by way of the Silk Road and the development of Chinese costumes. The brocade scarves found along the Silk Road reflect the prosperity of the silk trade that flourished in China's past (Lu & Xu, 2015).

I want to add to the above theory my own speculation that, what the Chinese considered to be dajin, was most likely an ancient Indian garment called uttariya उत्तरीय.

2. Personal conjecture: Uttariya as a tentative origin to pibo.

In India, since Vedic times (1500-500 BCE), we see mentions in records describing women and men wearing a thin scarf-like garment called “uttariya”. It is a precursor of the now famous sari. Although the most famous depiction of uttariya is when it is wrapped around the left arm in a loop, we do have other representations where it is draped over the shoulders and cubital area (reverse of the elbow).

Left: Hindu sculpture “Mother Goddess (Matrika)”, mid 6th century CE, gray schist. Artist unknown. Looted from Rajasthan (Tanesara), India. Photo credit to Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States [image source].

Right: Rear view of female statue possibly representing Kambojika, the Chief Queen of Mahakshatrapa Rajula, ca. 1st century CE. Artist unknown. Found in the Saptarishi Mound, Mathura, India. Government Museum, Mathura [image source].

Buddhism takes many elements from Hindu mythology, including apsaras अप्सरा (water nymphs) and gandharvas गन्धर्व (celestial musicians). The former was translated as feitian 飞天 in China. Hindu deities were depicted wearing clothes similar to what Indian people wore, among which we find uttariya, often portrayed in carvings and sculptures of flying and dancing apsaras or gods to show dynamic movement. Nevertheless, uttariya long predated Buddhism and Hinduism.

Below are carved representation of Indian apsaras and gandharvas. Notice how the uttariya are used.

Upper left: Carved relief of flying celestials (Apsara and Gandharva) in the Chalukyan style, 7th century CE, Chalukyan Dynasty (543-753 CE). Artist Unknown. Aihole, Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source]. The Chalukyan art style was very influential in early Chinese Buddhist art.

Upper right: Carved relief of flying celestials (gandharvas) from the 10th to the 12th centuries CE. Artist unknown. Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source].

Bottom: A Viyadhara (wisdom-holder; demi-god) couple, ca. 525 CE. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Nomu420 on May 10, 2014. Sondani, Mandsaur, India [image source].

Below are some of the earliest representations of flying apsaras found in the Mogao Caves, Gansu Province, China. An important pilgrimage site along the Silk Road where East and West met.

Left to right: Cave No. 461, detail of mural in the roof of the cave depicting either a flying apsara or a celestial musician. Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285 flying apsara (feitian) in one of the Mogao Caves. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE), Artist unknown. Photo taken by Keren Su for Getty Images. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 249. Mural painting of feitian playing a flute, Western Wei Dynasty (535-556 CE). Image courtesy by Wang Kefen from The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance, The Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 15. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

I theorize that it is likely that the pibo was introduced to China via Buddhism and Buddhist iconography that depicted apsaras (feitian) and other deites wearing uttariya and translated it to dajin.

3. Trickle down fashion: Buddhism’s journey to the East.

However, since Buddhism and its Indian-based fashion spread to West Asia first, to Sassanian Persians and Sogdians, it is likely that, by the time it reached the Han Chinese in the first century CE, it came with Persian and Sogdian influence. Persians’ fashion during the Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE) was influenced by Greeks (hellenization) who also had a a thin long scarf-like garment called an epliblema ἐπίβλημα, often depicted in amphora (vases) of Greek theater scenes and sculptures of deities.

Left to right: Dame Baillehache from Attica, Greece. 3rd century BCE, Hellenistic period (323-30 BCE), terracotta statuette. Photo taken by Hervé Lewandowski. Louvre Museum, Paris, France [image source].

Deatail view of amphora depicting the goddess Artemis by Athenian vase painter, Andokides, ca. 525 BCE, terracotta. Found in Vulci, Italy. Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany [image source].

Statue of a Kore (young girl), ca. 570 BCE, Archaic Period (700-480 BCE), marble. Artist unknown. Uncovered from Attica, Greece. Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece [image source].

Detail view of Panathenaic (Olympic Games) prize amphora with lid, 363–362 BCE, Attributed to the Painter of the Wedding Procession and signed by Nikodemos, terracotta. Uncovered from Athens, Greece. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, United States [image source].

Roman statue depicting Euterpe, muse of lyric poetry and music, ca. 2nd century CE, marble, Artist unknown. From the Villa of G. Cassius Longinus near Tivoli, Italy. Photo taken by Egisto Sani on March 12, 2012, Vatican Museums, Rome, Italy [image source].

Greek (or Italic) tomb mural painting from the Tomb of the Diver, ca. 470 BCE, fresco. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Floriano Rescigno. Necropolis of Paestum, Italy [image source].

Below are Iranian and Iraqi period representations of this long thin scarf.

Left to right: Closeup of ewer likely depicting a female dancer from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia , Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 10, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Ewer with nude dancer probably representing a maenad, companion of Dionysus from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia, Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 16, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Painting reconstructing the image of unveiled female dancers depicted in a fresco, Early Abbasid period (750-1258 CE), about 836-839 CE from Jawsaq al-Khaqani, Samarra, Iraq. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul [image source].

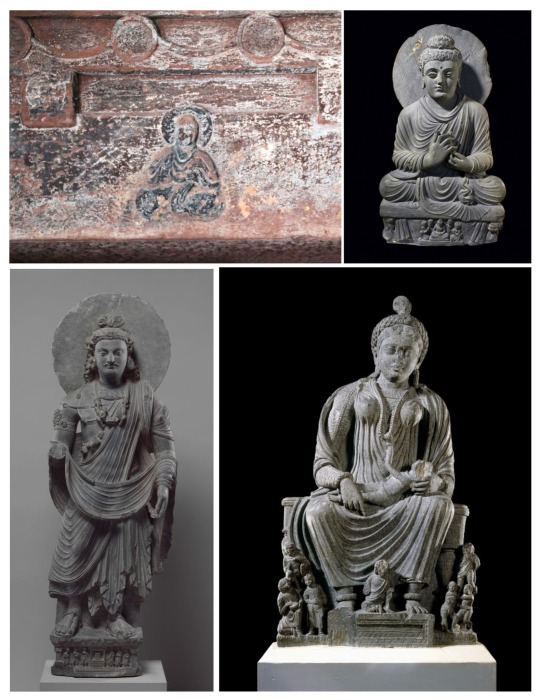

The earliest depictions of Buddha in China, were very similar to West Asian depictions. Ever wonder why Buddha wears a long draped robe similar to a Greek himation (Romans called it toga)?

Take a look below at how much the Greeks influenced the Kushans in their art and fashion. The top left image is one of the earliest depictions of Buddha in China. Note the similarities between it and the Gandhara Buddha on the right.

Left: Seated Buddha, Mahao Cliff Tomb, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han Dynasty, late 2nd century C.E. (photo: Gary Todd, CC0).

Right: Seated Buddha from Gandhara, Pakistan c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Standing Bodhisattva Maitreya (Buddha of the Future), ca. 3rd century, gray schist. From Gandhara, Pakistan. Image credit to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States [image source].

Statue of seated goddess Hariti with children, ca. 2nd to 3rd centuries CE, schist. Artist unknown. From Gandhara, Pakistan. The British Museum, London, England [image source].

Before Buddhism spread outside of Northern India (birthplace), Indians never portrayed Buddha in human form.

Early Buddhist art is aniconic, meaning the Buddha is not represented in human form. Instead, Buddha is represented using symbols, such as the Bodhi tree (where he attained enlightenment), a wheel (symbolic of Dharma or the Wheel of Law), and a parasol (symbolic of the Buddha’s royal background), just to name a few. […] One of the earliest images [of Buddha in China] is a carving of a seated Buddha wearing a Gandharan-style robe discovered in a tomb dated to the late 2nd century C.E. (Eastern Han) in Sichuan province. Ancient Gandhara (located in present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India) was a major center for the production of Buddhist sculpture under Kushan patronage. The Kushans occupied portions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and North India from the 1st through the 3rd centuries and were the first to depict the Buddha in human form. Gandharan sculpture combined local Greco-Roman styles with Indian and steppe influences (Chaffin, 2022).

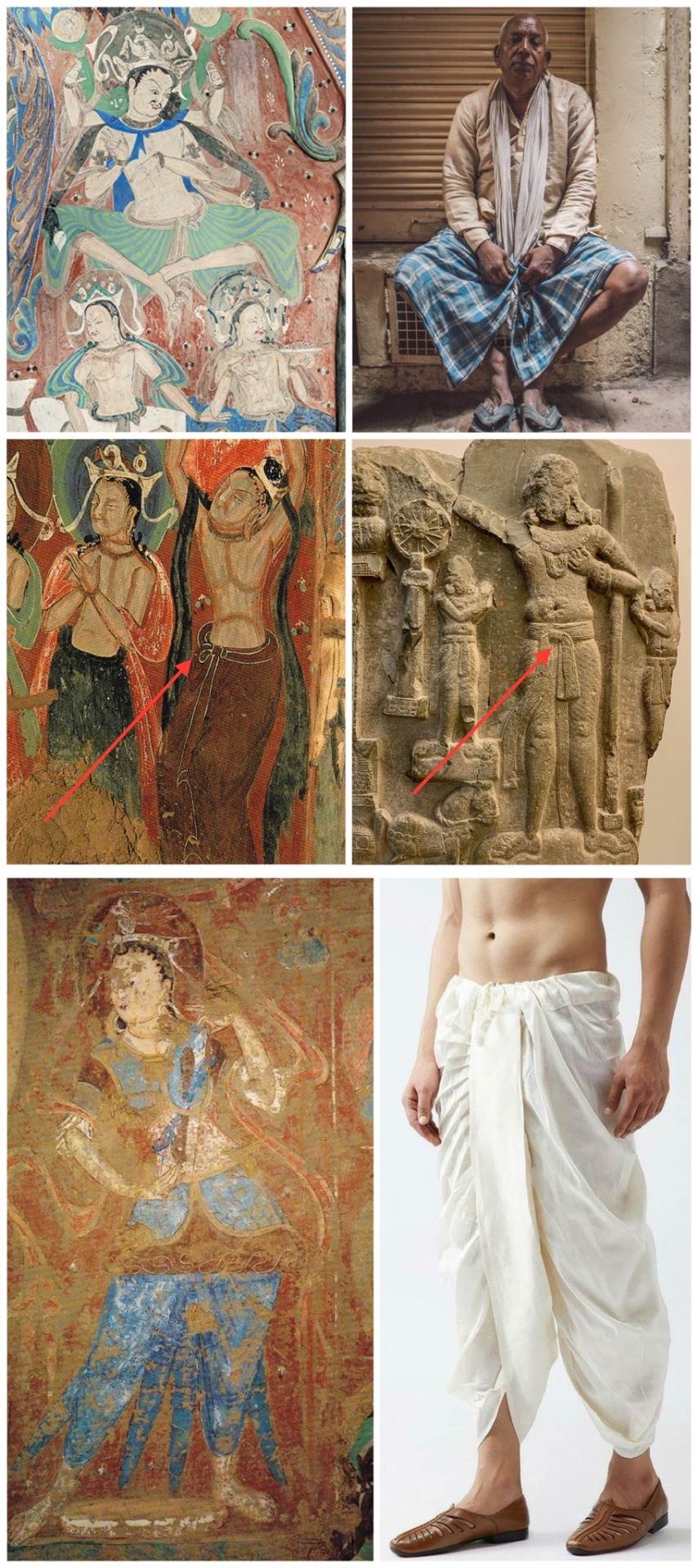

In the Mogao Caves, which contain some of the earliest Buddhist mural paintings in China, we see how initial Chinese Buddhist art depicted Indian fashion as opposed to the later hanfu-inspired garments.

Left to right: Cave 285, detail of wall painting, Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Courtesy the Dunhuang Academy [image source]. Note the clothes the man is wearing. It looks very similar to a lungi (a long men’s skirt).

Photo of Indian man sitting next to closed store wearing shirt, scarf, lungi and slippers. Paul Prescott. February 20, 2015. Varanasi, India [image source].

Cave 285, mural depiction of worshipping bodhisattvas, 6th century CE, Wei Dynasty (535-556 A.D.), Unknown artist. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Notice the half bow on his hips. That is a common style of tying patka (also known as pataka; cloth sashes) that we see throughout Indian history. Many of early Chinese Buddhist paintings feature it, including the ones at Mogao Caves.

Indian relief of Ashoka wearing dhoti and patka, ca. 1st century BC, Unknown artist. From the Amaravathi village, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Currently at the Guimet Museum, Paris [image source].

Cave 263. Mural showing underlying painting, Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535 CE). Artist Unknown. Picture taken November 29, 2011, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source]. Note the pants that look to be dhoti.

Comparison photo of modern dhoti advertisement from Etsy [image source].

Spread of Buddhism to East Asia.

Map depicting the spread of Buddhism from Northern India to the rest of Asia. Gunawan Kartapranata. January 31, 2014 [image source]. Note how Mahayana Buddhism arrived to China after passing through Kushan, Bactrean, and nomadic steppe lands, absorbing elements of each culture along the way.

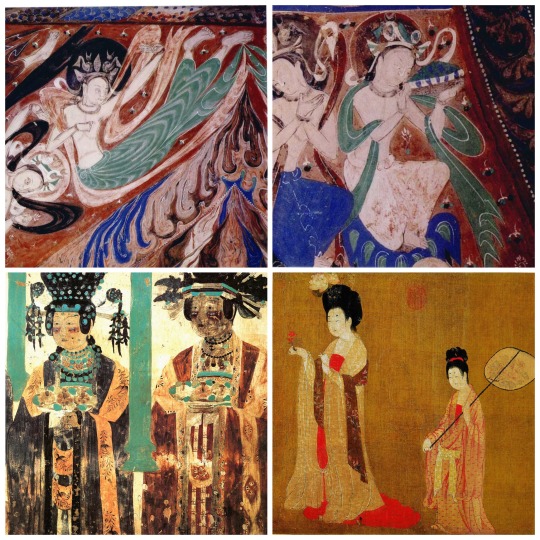

Wealthy Buddhist female patrons emulated the fantasy fashion worn by apsaras, specifically, the uttariya/dajin and adopted it as an everyday component of their fashion.

Cave 285. feitian mural painting on the west wall, Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285. Detail view of offering bodhisattvas (bodhisattvas making offers to Buddha) next to the phoenix chariot on the Western wall of the cave. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 61 Khotanese (from the kingdom of Khotan 于阗 [56–1006 CE]) donor ladies, ca. 10th century CE, Five Dynasties period (907 to 979 CE). Artist unknown. Picture scanned from Zhang Weiwen’s Les oeuvres remarquables de l'art de Dunhuang, 2007, p. 128. Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons on October 11, 2012 by Ismoon. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Detail view of Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers 簪花仕女图, late 8th to early 9th century CE, handscroll, ink and color on silk, Zhou Fang 周昉 (730-800 AD). Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China [image source].

Therefore, the theory I propose of how the pibo entered East Asia is:

India —> Greek influenced West Asia (Sassanian Persians, Sogdians, Kushans, etc…) —> Han China —> Rest of East Asia (Three Kingdoms Korea, Asuka Japan, etc…)

Thus, the most likely theory, in my person opinion, is Buddhist iconography depicting uttariya encountered Greek-influenced West Asian Persian, Sogdian, and Kushan shawls, which combined arrived to China but wouldn’t become commonplace there until the explosion in popularity of Buddhism from the periods of Northern and Southern Dynasties to Song.

References:

盧秀文; 徐會貞. 《披帛與絲路文化交流》 [The brocade scarf and the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road]. 敦煌研究 (中國: 敦煌研究編輯部). 2015-06: 22 – 29. ISSN 1000-4106.

#hanfu#chinese culture#chinese history#buddhism#persian#sogdian#kushan#gandhara#indian fashion#uttariya#pibo#history#asian culture#asian art#asian history#asian fashion#east asia#south asia#india#pakistan#iraq#afghanistan#sassanian#silk road#fashion history#tang dynasty#eastern han dynasty#cultural exchange#greek fashion#mogao caves

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portraits of Áo Dài by Chiron Duong

Portraits of Áo Dài series by photographer Chiron Duong.

Who is Chiron Duong? The architect turned photographer who portrays the many shades of Ao Dai, the traditional Vietnamese costume [read more at Vogue].

Where can I find out more about him? chironduong.com

Where can I see more of his work? chironduong [on Instagram]

#ao dai#vietnam#vietnamese fashion#traditional vietnamese clothing#viet phuc#chiron duong#photography#portraits of ao dai#portrait photography#asia#asian photography#asian fashion#asian art#art

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Google New Year Animations:

When you go on Google and type “[insert Asian country that celebrates Lunar New Year] New Year”, you will be greeted with a firework and a rabbit/cat animation (depending on the country). A rabbit for China and other countries that use the same animal zodiac and a cat for Vietnam since 2023 is the Year of the Cat there. It’s the little things…

Screenshots of animations that show up when you search “Chinese New Year” and “Korean New Year” respectively on Google. Since both countries share the same zodiac, it’s the year of the rabbit for both.

Screenshot of animation that shows up when you search “Vietnamese New Year” on Google. The Vietnamese zodiac replaces the rabbit for the cat as the fourth zodiac animal.

#chinese new year#korean new year#vietnamese new year#春节#spring festival#seollal#설날#tết nguyên Đán#lunar new year#google#asian culture#asia#it’s the little things#year of the rabbit#year of the cat

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mongolian Women Series by Artist Su Ruya.

Mongolian Noble Women. Su Ruya. Painting, 2017 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 9, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2002 [image source].

Mongolian Women No. 2, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting [image source].

Mongolian Women No. 1, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 1998. [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 10, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2002 [image source].

Golden Age. Su Ruya. Painting, 2014 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 15, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2015 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 5, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2000 [image source].

#mongolia#inner mongolia#chinese art#china#chinese artists#inner mongolian artists#asian art#mongolian fashion#traditional mongolian fashion#su ruya#su ruya artist#painting#art#boqta#gugu hat

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

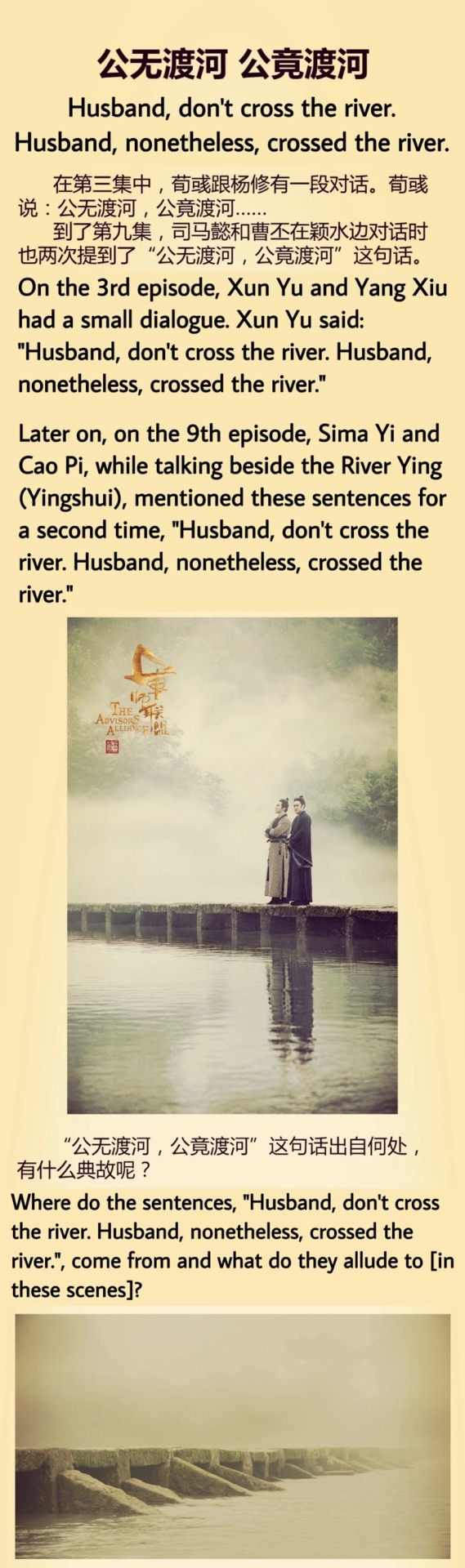

The Advisors Alliance Translation Post 2: “Husband, don’t cross the river. Husband, nonetheless, crossed the river.”

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Hidden Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

Extra information:

Yuefu (乐府), literally Music Bureau, are a genre of ancient Chinese folk songs that, either imitate the style of, or are from the Imperial Music Bureau. The latter was an institution in charge of collecting and writing lyrics to folk songs. Yuefu are known for having strict syllabic rules that change from dynasty to dynasty.

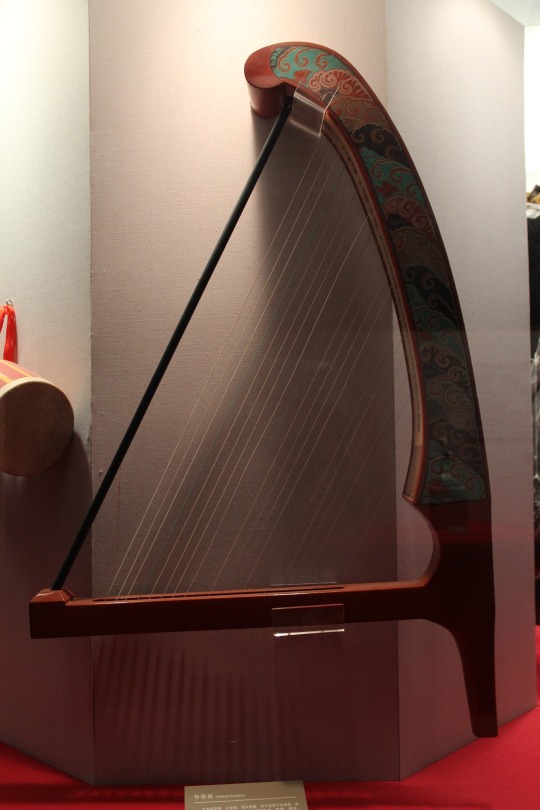

《公无渡河》 is also known as Kong Hou Yin (箜篌引). Konghou is an ancient Chinese stringed instrument similar to a harp. A Yin (引), in this context, is another type of ancient music poetry that has a freer syllabic structure and is characterized by long syllables that go well with the melody of the konghou. Below is a picture of the instrument:

Vertical konghou 箜篌 in exhibit at the Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou, China. Taken on May 10, 2013 by Gary Todd [image source].

Allow me to clarify something. The folk song 《公无渡河》 was recorded by Cui Bao in "Notes on Ancient and Modern Times" to be of Gojoseon origin. As such, Koreans consider it to be their oldest surviving folk song.

The Chinese consider it a Chinese Han Dynasty song on account of the tale being set and song created in the Lelang Commandery [108 B.C.E. - 313 C.E.] which is one of the four regions Gojoseon was split into while under Han rule. Koreans consider the residents of Lelang, and the other commandaries, to be Gojosen Koreans who retained a separate culture to the Han Chinese. If you wish to conduct further research into the song, don’t get surprised if you read different names for the characters that appear in the story.

Koreans call the song "Gongmudohaga (공무도하가)” and the ferryman Gwaklijago (곽리자고). The Korean folk tale differs from the Chinese retelling in that the Korean name of Gwaklijago wife, who is credited with creating the actual song, according to certain Chinese and Korean retellings, is Yeo-ok (여옥) rather than Li Yu (丽玉). In Cao Yong and Cui Bao’s retellings, the wife of the drowned drunk man created the song while, in the Korean version, it was the wife of the ferryman who, upon learning about what had transpired from her husband once he came home, created the song on her harp, called in Korean gonghu (공후).

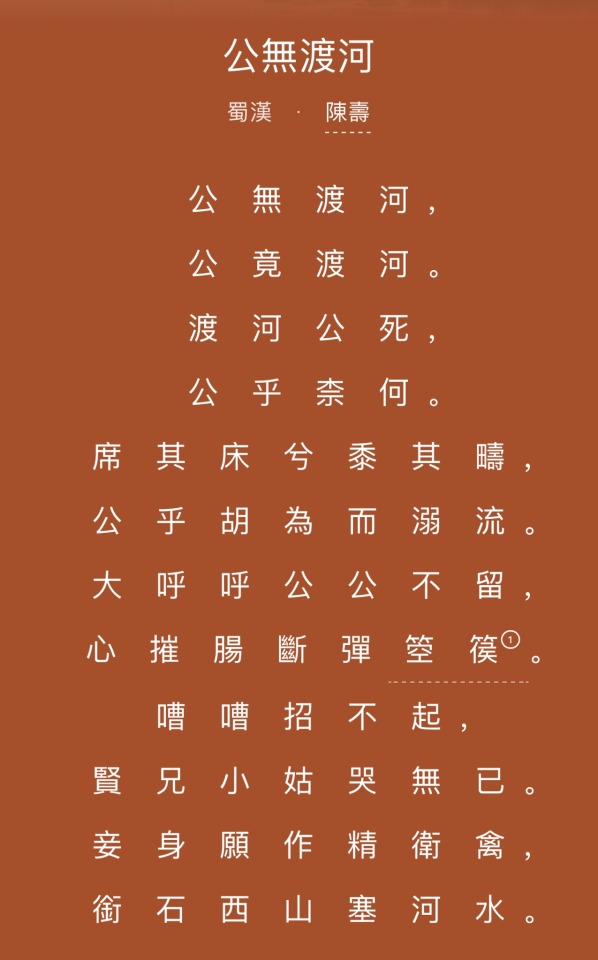

Many Chinese poets have retold the story in their own ways and added, omitted, or reinterpreted content. Some of said poets are Li Bai and Chen Shou of Shu Han. On top is Li Bai's version which lacks strict syllabic structure, a signature of his style and, on the bottom, Chen Shou's more structured one:

This expression 《公无渡河, 公竟渡河》 is often used as an allegory to satirize someone who is heading into clear danger but is too stubborn or obsessed to listen. If this person doesn't listen, then they are sure to run into trouble.

Catalogue (find the rest of the posts):

#chinese culture#chinese history#the advisors alliance#sima yi#history#three kingdoms#eastern han dynasty#korean folklore#li bai#chinese poetry#ancient chinese poetry#ancient china#gojoseon#korea

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vietnamese paintings from Vietnamese-French artists Lê Phổ (1907-2001) and Mai Trung Thứ (1906-1980)

Vietnamese lady 越南女士. Lê Phổ. Ink and gouache on silk. ca. 1938. Important Private American Collection. Sotheby’s [image source].

Idylle (Idyll). Lê Phổ. Ink and gouache on silk. c.a. 1940s. Private Collection, France. Christie’s [image source].

Portrait de jeune femme à la branche de lotus. (Portrait of a young woman with a lotus branch). Lê Phổ. Ink and gouache on silk laid on board, 1939. Private Collection, USA. Sotheby’s [image source].

><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

"Trong dam gi dep bang sen

Lá xanh bông trang lai chen nhi vang

Nhi vang, bông trang, lá xanh

Gan bun mà chang hôi tanh mui bun.”

— Một bài thơ truyền thống Việt Nam

><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

"In a pond, what is more beautiful than a lotus,

Green leaves and white petals surround yellow stamens.

Oh, yellow stamens, white petals, and green leaves,

Though near mud you grew, your smell is still perfumed”

— A Vietnamese traditional poem

><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

Harmonie verte: Les deux sœurs (Harmony in Green: The Two Sisters). Lê Phổ. Gouache on silk, 1938. Collection of National Gallery Singapore, Singapore [image source].

Jeune fille en blanc (Young Girl in White). Lê Phổ. Gouache on silk, c.a. 1931-1932. Christie’s [image source].

Maternité (Motherhood). Lê Phổ. Ink and color on silk, 1940. Private Collection, Paris. Aguttes [image source].

Grand-mère (Grandmother). Mai Trung Thứ. Ink and gouache on silk mounted on cardboard, 1944. Private Collection, Spain. Sotheby’s [image source].

L'Heure du thé (Tea Time). Mai Trung Thứ. Ink and gouache on silk, 1945. Invaluable [image source].

A l'approche du tet (As Tet Approaches). Lê Phổ. Ink and color on silk [image source].

Note: the word “tet (Tết)” is short for Tết Nguyên Đán (“Festival of the First Day of the Year”). It’s the most sacred festival for the Vietnamese. It’s the Lunar New Year in the Vietnamese calendar. It celebrates the arrival of Spring which falls between January and February in the Gregorian calendar.

#vietnam#vietnamese#vietnamese art#vietnamese painters#le pho#mai trung thu#asian art#ao dai#Tết#Tết Nguyên Đán

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hulos: Elevating the Áo Dài to Haute Couture

This áo dài collection took inspiration from the ancient royal robes that were in vogue during the Nguyen Dynasty. It combines three dimensional hand embroideries of phoenixes and dragons – Asian symbols of royalty – with intricate cast bronze decorations. The collection represents an idealized image of Asian beauty – luxurious and seductive while evoking mystery and intrigue. These unique designs were specially created to promote and preserve Vietnam’s cultural heritage.

Oi Vietnam, 2014

“Fashion is the bridge to bring Vietnamese, our beloved country’s culture to the world. Many designers approach fashion by looking forward to its magnificence, but then lost themselves in its frivolously and flashy. In our opinion, fashion is not only talent itself, but also a demonstration of many skills and understanding in many aspects. A designer is also a psychologist, a politician, an architect, an economist, a scientist, and many other jobs. To exist in this industry, a designer need resolves and experience…We follow the Buddhist teaching. The philosophy of Buddhist teaches us many lessons to help us grow up. My principles of living are sharing, live slowly, think differently and love more. If I am a super hero, I want a power which can transform other everybody to be good because a fashion designer can only create external beauty, but cannot perfect people soul”

David Leung, 2017

Vietnamese designer duo, Huỳnh Hải Long and Đặng Thế Huy, along with their brand, Hulos, breathe new life into áo dài by re-envisioning and presenting it to a new generation of Vietnamese and international audiences.

Áo dài’s simple yet elegant form allows it to adapt easily to changing environments and generational tastes.

Sources:

Hulos website: www.hulosprive.com

Hulos Instagram: hulosbythehuyhailong

#vietnam#ao dai#nguyen dynasty#vietnamese#vietnamese culture#asia#asian fashion#Huỳnh Hải Long#Đặng Thế Huy#hulos prive#viet phuc#越服#viet phuc movement

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

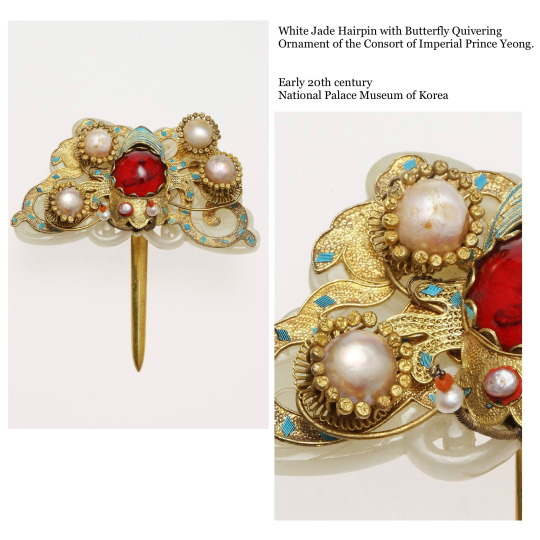

Jewelry of Consort of Imperial Prince Yeong, Crown Princess Uimin (1901-1989).

One of a pair of white jade ornamental hairpins with phoenix head-shaped design. Used in upright position on a braided wig, it is decorated with gold thread, pearl, red and blue crystal beads, and kingfisher feather on top of the white jade phoenix. This hairpin is part of a daesu 대수 ensemble. A Joseon wig worn by Queens for ceremonial occasions resembling a helmet [image source].

This women’s ornamental pendant, Norigae was made by vertically connecting two pieces of white jade plates. Each jade plate is decorated with a pierced open work of a butterfly. Norigaeis an ornamental pendant for women, which is worn by being hung from the top garment or skirt with a string. It is one of the pendants which Lady Hyoyeong, the consort of Imperial Prince Regent of Gang, presented to the consort of Imperial Prince Yeong in 1941 [image source].

Jade hairpin in the shape of a flower worn with daesu. Kingfisher feathers are inlaid between delicate gilt gold framework in the shape of various flowers and phoenixes. Blue and red glass stones adorn the pin along with pearls [image source]

This is a silk-lantern-shaped hairpin made of jade. The head of the harpin is sculpted after intertwined tree branches in openwork, with plum blossoms, bamboo leaves, and birds represented in between [image source].

Bongjam is a phoenix-shaped hairpin. It has 6 pearls decorating the tail, wings, and eyes of the phoenix, three red glass stones at the end of the tail, top of the head, and front of the bottom support, and two blue glass stones on the sides. The red glass stone at the front is framed by an 8-petal flower decorated with kingfisher feathers [image source].

One of a pair of hairpins used by the Consort of Imperial Prince Yeong for her daesu, worn together with a ceremonial pheasant robe. The head of the hairpin is carved in the shape of a dragon holding the pearl of wisdom in its mouth. The mouth, filled with red beeswax, has a red glass bead inside, but only small portion of the bead is visible. The whole piece is gold-plated, but two small pearls which had been studded in the eyes are missing [image source].

A plum blossom is embossed at the center of a milky-white jade in the shape of a chrysanthemum. An eight-lobed metal support is placed on top of it. Golden stamens were added and shaped with a technique called eojamun 어자문 to flatten the top. Kingfisher feathers are used to decorate the support at the center. Finally, a red glass stone was added on top [image source].

Hairpin in the shape of a butterfly worn along with the daesu. Four large pearls flank the corners of the wings to create flowers. Golden stamens surround them. At the center is a lotus flower with a red glass stone. Eojamun technique was employed to decorate the frame with small rounded indentations where kingfisher feathers were inlaid on top [image source].

A one of a pair of phoenix hairpins used with the daesu. This type is worn horizontally [image search].

This hair ornament is to be vertically placed in the front of the queen’s wig. It is made of carved white jade connected with a gold-plated skewer. It was usually worn with a pheasant robe. Both sides of the white jade plate, where circular longevity symbols, a phoenix, and arabesque patterns are carved in relief, are decorated with pearls and blue and red crystal beads [image source].

#korea#korean#korean traditional jewelry#joseon empire#crown princess uimin#imperial prince yeong#joseon#eojamun#asia#asian jewelry#jewelry#hanbok#history

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

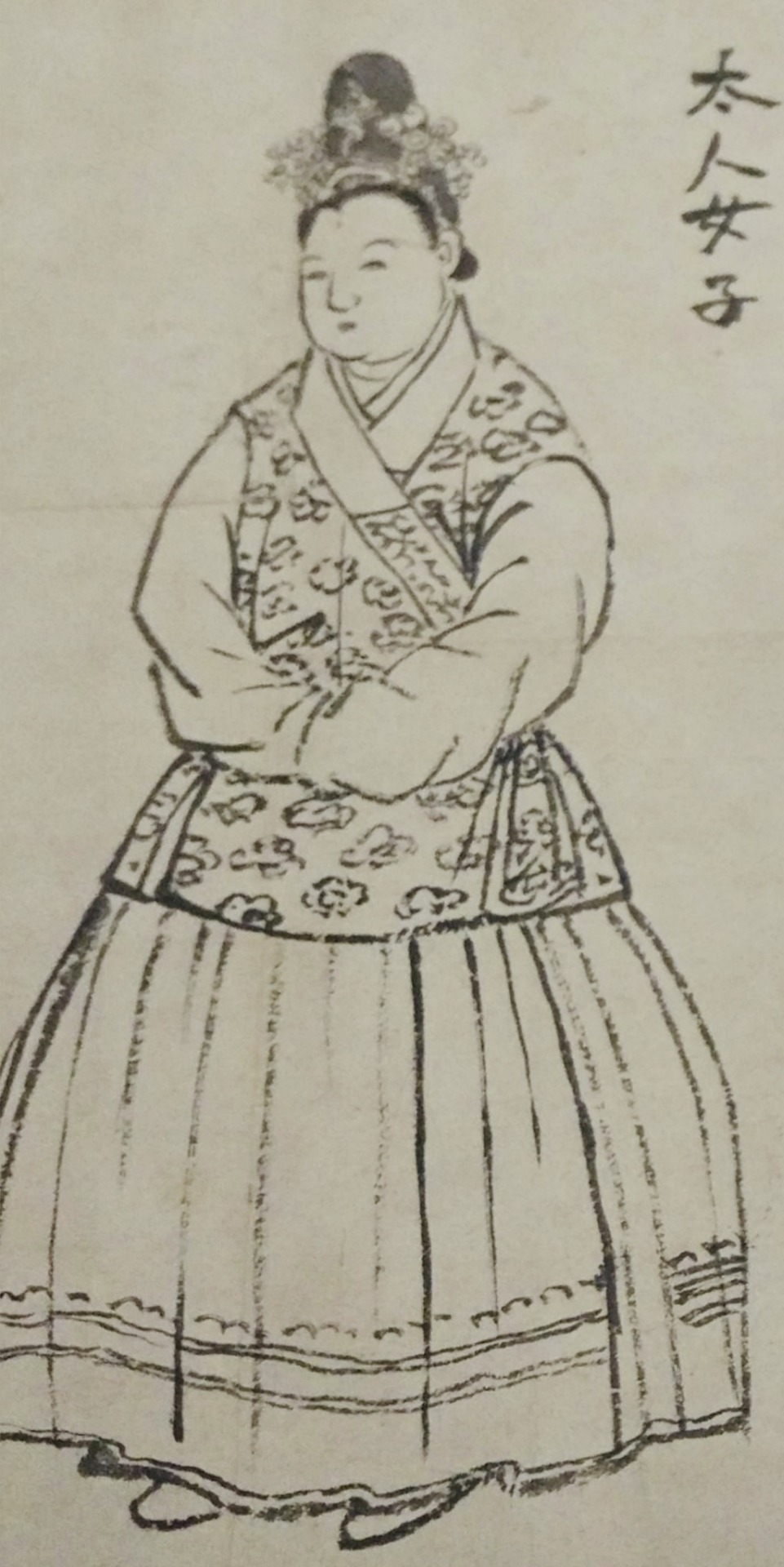

Rare Portraits Depicting Hanfu Worn with Right Over Left Lapel Closing (左衽).

Thirteenth Ancestor Portrait from Portrait Album of Wu’s Ancestors 吳氏先祖容像十三. Ni Renji. Painted sometime between the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty during the artist’s life (1607-1685). Yiwu Museum, Zhejiang, China [image source].

For the Han, the left lapel was considered Yang and the right one Yin and, thus, living people placed the left lapel over the right one to symbolize Yang (life) covering Yin (death). That’s why only dead people had their right lapel over their left. In the case of the dead, Yin (death; right lapel) overtook Yang (life; left lapel). Moreover, the left over right lapel (右衽) served as an ethnic distinction for the Han.

However, not all living Han people followed this tradition and there are documented cases of them wearing their hanfu with the right lapel over the left one.

There are exceptions in which living Han Chinese would wear clothing with a zuoren closure. For example, in some areas (such as Northern Hebei) in the 10th century, some ethnic Han Chinese could be found wearing left-lapel clothing. It was also common for the Han Chinese women to adopt left lapel under the reign of foreign nationalities, such as in the such as in the Yuan dynasty. The practice of wearing the zuoren also continued in some areas of the Ming dynasty despite being a Han Chinese-ruled dynasty which is an atypical feature.

Wikipedia, Garment collars in Hanfu

Fifth Ancestor Portrait from Portrait Album of Wu’s Ancestors 吳氏先祖容像五. Ni Renji. Painted sometime between the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty during the artist’s life (1607-1685). Yiwu Museum, Zhejiang, China [image source].

Other non-Han ethnicities, such as the Khitans and Xianbei, would preserve their 左衽 tradition even after adopting hanfu. It’s possible for these women (and its mostly women wearing hanfu depicted with 左衽) to be non-Han in origin or are Han but came from areas where 左衽 was still practiced due to non-Han ethnic influence. I remember reading somewhere that, South of the Yangtze, certain Han women wore their hanfu in both styles.

Since almost all of the portraits below are ancestor portraits and there are plenty of those where the women and men wear 右衽 despite being dead at the time of painting, it’s unlikely that the 左衽 depicted is meant to indicate that the woman is dead.

Portrait of the wife of a dignitary with maid by Chow Ying. Scroll. Painting on silk. 16th century. Moscow State Museum of Oriental Art [image source].

Portrait of Father Zhang Jimin and Mother Zhao. Unknown artist. Ming or Qing dynasty, Late Ming or early Qing dynasty (17th century or later). Hanging scroll. Ink and colors on silk. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution [image source].

Ancestor Portrait of a Court Lady. Possibly Ming Dynasty. Unknown artist. Hanging scroll (laid down on panel), ink and color on silk. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art [image source].

Notice how, even the maid in the background above, has 左衽.

Possible Portrait of Ancestor with maid. Unknown Artist. Possibly Ming Dynasty [image source].

Ancestor Portrait. Unknown artist. Late 19th century. Qing Dynasty. Auguttes Auction House. [image source].

Note: Be careful when dating ancestor portraits. Many were painted posthumously and could depict ancestors from multiple previous generations. Just because the figures are seen wearing a dynasty’s distinctive clothing, does not necessarily mean that it was painted then. Some Qing Dynasty ancestor portraits depict ancestors from the Ming Dynasty and, thus, artists painted the figures with Ming clothing.

Images portraying hanfu in the Ming Dynasty with 左衽 drawn by Sesshu Toyo (1420 - 1506 CE), a Japanese monk who visited China between 1467 to 1469. Ink on paper [image source].

More portraits with 左衽 and modern recreation:

#chinese history#chinese culture#ming dynasty#ancestor portraits#右左衽#hanfu#ming paintings#ming portraits

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

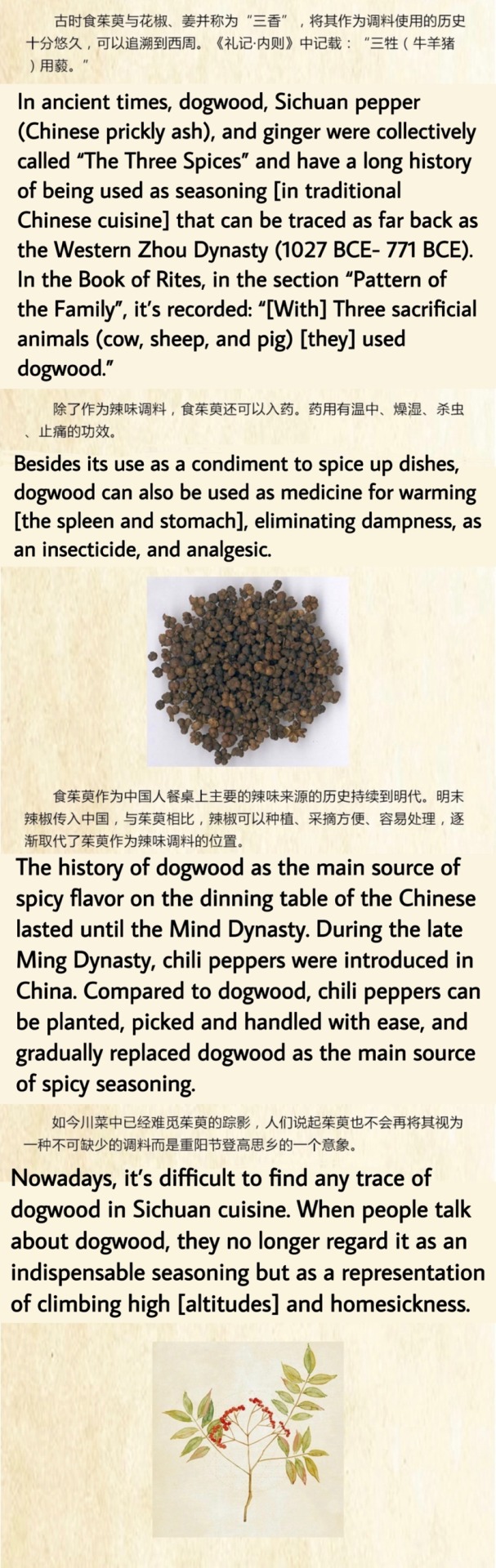

Advisors Alliance Mini Encyclopedia Translation Post 19: Dogwood

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Roaring Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

There’s a typo. I meant “Ming Dynasty” not “Mind Dynasty”.

Extra information:

Double Ninth Festival, also known as Double Yang Festival and Chongyang Festival, is a Chinese holiday celebrated on the ninth day of the ninth month in the traditional Chinese calendar. It’s called the Double Yang Festival 重阳节 [Trad. 重陽節] because nine, in Chinese culture, was regarded to be a Yang number (6 was Yin). As such, the ninth day of the nine month was considered to have very strong Yang energy and, thus, was auspicious. People celebrated it by climbing high places such as mountains (from there the festival also came to be known as the Height Ascending Festival 登高节), drinking chrysanthemum wine, eating chrysanthemum cakes, appreciating chrysanthemum flowers, wearing dogwood branches on the hair, and visiting the graves of ancestors to leave food, drinks, and gifts. The tradition of climbing mountains likely came from the worship of mountains as ancient Chinese people climbed them to pray and receive blessings from the gods and/or ancestors. The Double Ninth Festival predates the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Like all other traditional Chinese holidays, poets wrote poems dedicated to celebrating the auspicious days. The fragment of the poem that is mentioned at the beginning of the post is one taught to children in China in elementary school. It’s by the Tang poet Wang Wei 王维 and it’s titled 《九月九日忆山东兄弟》 [Trad. 《九月九日憶山東兄弟》]. Below is the poem in both simplified and traditional Chinese. I will leave a translation made by American Poet Witter Bynner below.

Traditional:

獨在異鄉為異客,

每逢佳節倍思親。

遙知兄弟登高處,

遍插茱萸少一人。

Simplified:

独在异乡为异客,

每逢佳节倍思亲。

遥知兄弟登高处,

遍插茱萸少一人。

Translation (On the Mountain Holiday Thinking of my Brothers in Shandong)

All alone in a foreign land,

I am twice as homesick on this day.

When brothers carry dogwood up the mountain,

Each of them a branch -- and my branch missing.

The three sacrificial animals 三牲 changed depending on the dynasty. For instance, nowadays, people associate the three sacrificial animals with chicken, pork, and fish. However, in the time of the Western Zhou Dynasty, people referred to the three sacrificial animals as cow, sheep, and pig. Variations also include chicken, duck (or geese), and fish. Another variation involves five animals instead of three: chicken, duck, pork, fish, and squid. The purpose of animal sacrifice was to ask the gods and ancestors for protection and/or blessings.

Picture showcasing the five animal sacrifices 五牲 of chicken, pork, fish, duck, and squid [image source].

Catalogue (find the rest of the posts):

#chinese culture#chinese history#the advisors alliance#history#food history#food#dogwood#double yang festival#eastern han dynasty#western zhou dynasty#three kingdoms#wang wei#chinese poetry

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

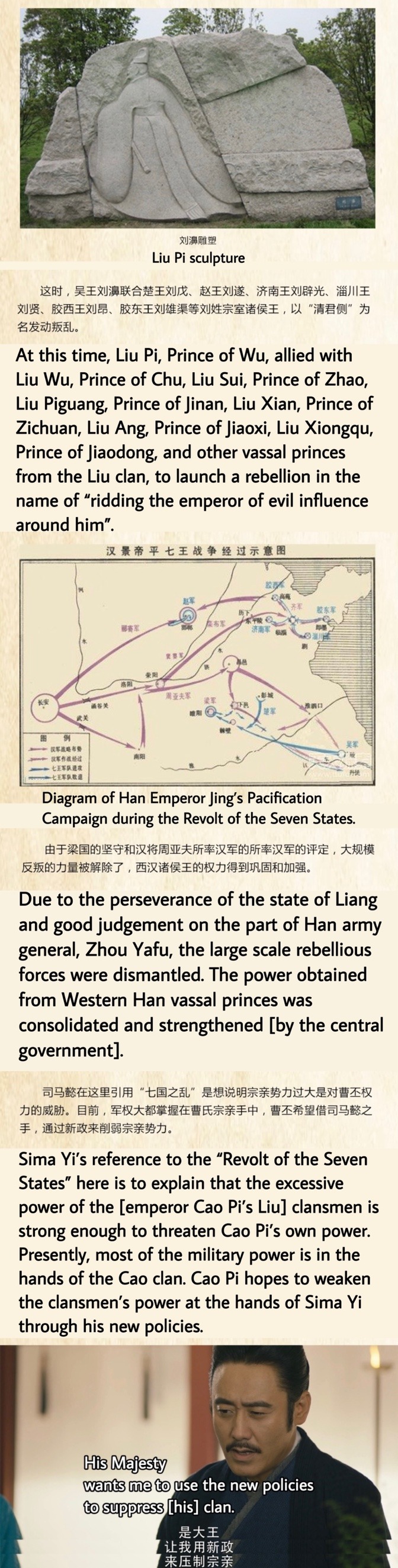

The Advisors Alliance Mini Encyclopedia Translation - Post 15: Revolt of the Seven States

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Roaring Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

Extra information

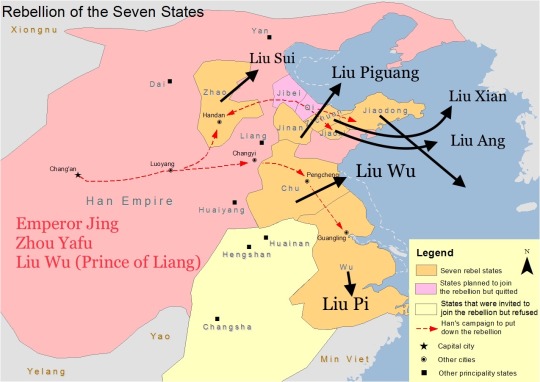

Below is a handy map to picture the conflict better:

Map showcasing the states involved in the Revolt of the Seven States (154 BCE) created by Wikipedia user Seasonsinthesun. Posted July 8, 2017. I added the black arrows and names of the historical figures involved for readers’ convenience [image source].

Let me clarify something. 王 is “king” in Chinese. However, that title only applies to a ruler in ancient China before it became an empire and the title “emperor” 皇帝 was created. Thus, when we are talking about pre-imperial China, in English, the title 王 is translated as “king”. Once China unified and became an empire, to appease regional lords of states, the emperors allowed them to keep the title of “王” while the emperors took the title of 皇帝. However, in English, we, for the most part, do not translate the rulers of states after China unified as “kings”. Instead, we translate them as “princes”. It’s important to note that the phrase “大王” Great King (His Majesty) was used by emperors in ancient China despite containing 王. The further back we go, the blurrier it gets between 皇帝 and 王 and, sometimes, some 皇帝 preferred to go by 王 instead.

When Liu Bang, the founder of the Han Dynasty, ascended to the imperial throne, he took the title of 皇帝 and gave his allies land (states) that would operate as their own (mostly) independent kingdoms and granted them the title of “王” (Prince). Nevertheless, he had them all killed and replaced by his own kin, the Liu clan. That’s why, in the post above, you see so many princes with the names “Liu”. This was a terrible miscalculation because, in consolidating more power for his family, Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu of Han) created a fractured empire with kingdoms that were independent and even minted their own coins (created their own currency). This independence made these states unwilling to follow the orders and laws of the central government (the imperial court).

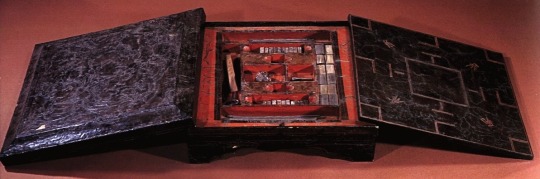

By the reign of emperor Jing of Han, the personal relationship between him and several vassal princes was gravely strained thanks, in no small part, to Jing (then crown prince Qi) killing the vassal Prince of Wu, Liu Pi’s heir apparent, Liu Xian. Crown prince Qi and Liu Xian, while drunk, disagreed over the rules of the board game they were playing called Liubo 六博, a chess-like game tied to divination. Seeing as how Liu Xian, who was from a lower rank as the son of a vassal prince, dared to staunchly disagree with the crown prince, Qi, in what could only be described as a fit of drunken derangement, grabbed the hefty wood board, scattering the pieces to the ground, and proceeded to violently bludgeon Liu Xian in the head, eventually killing him. That act, along with the Vassal Domain Reduction Policy, triggered Liu Pi to start a revolt against centralized power. Below is what a Liubo set looks like:

Lacquered Liubo chess set excavated from Han Tomb No.3 (believed to have been of the son of the Marquis of Dai), Mawangdui, Changsha city, Hunan. Early Western Han (206 BCE – 25 CE), 12th year of Emperor Han Wendi (168 BCE). This Liubo set was around the time period of Crown Prince Qi and is likely to resemble the actual set he used to kill Liu Pi’s son, Liu Xian. This set is currently at the Hunan Provicial Museum.

A close up of a pair of Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE) ceramic tomb figurines of two gentlemen playing Liubo. Earthenware figures displayed at the Met Museum [image source].

Note: The two Liu Xian mentioned here aren’t the same. They are both called Liu Xian and both names are written as 刘贤 (Trad. 劉賢) but one is the Prince of Zichuan and the other is the son of Liu Pi.

Note: Another name that repeats is Liu Wu. There are two different Liu Wu. The first is Liu Wu 刘戊 (Trad. 劉戊) Prince of Chu, ally to Liu Pi, and the other is 刘武 (Trad. 劉武), Prince of Liang, ally to Emperor Jing.

The “good judgement” on the part of Zhou Yafu in the text refers to him purposely disobeying Emperor Jing’s orders to save Prince of Liang, Liu Wu. Instead, Zhou, opted to cut off the supply lines of the states Chu and Wu creating a decisive defeat for those two states and a victory for the emperor and Zhao.

Catalogue (Find the rest of the posts)

#chinese history#chinese culture#history#the advisors alliance#eastern han dynasty#western han dynasty#han dynasty#liubo#ancient chinese board game#revolt of the seven states#rebellion of the seven states#rebellion of the seven kingdoms#cao pi#sima yi#emperor jing of han#emperor wen of han

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Growling Tiger and Roaring Dragon Mini Encyclopedia Translation Post 24: Wine Rinse & Nuptial Wine

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Roaring Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

Extra information:

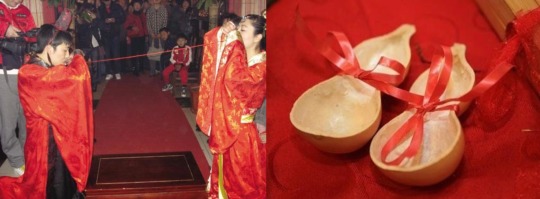

Left image: modern reenactment of 合卺 [image source].

Right image: a drinking gourd split into two with the halves tied at the center with a red string, an ancient Chinese wedding tradition [image source].

A modern wedding ceremony showcasing jiaobeijiu [image source].

A contemporary 亲迎 (sometimes written as 迎亲) procession [image source].

Catalogue (Find the rest of the posts)

#chinese history#chinese culture#history#the advisors alliance#growling tiger roaring dragon#qing dynasty#traditional chinese wedding#wedding#three kingdoms

61 notes

·

View notes

Video

This post reminded me of a connection so, please, don’t mind me adding some extra information.

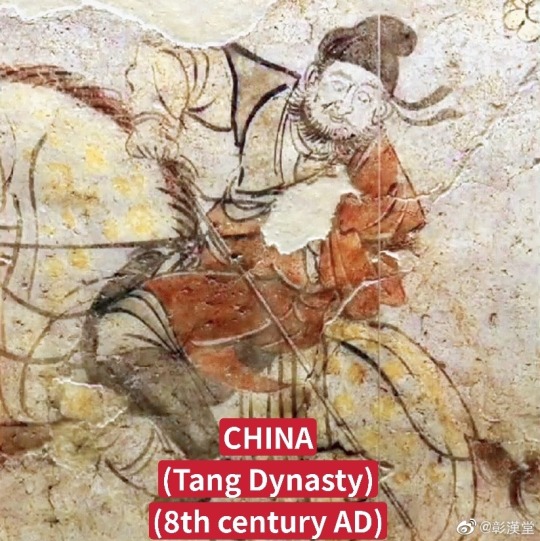

The specific trend of hanfu worn here was one used during the Tang Dynasty, specifically for archery and/or horse riding. It’s composed of a white silk round collar undershirt 圆领汗衫中衣, a jacket called a banbi 半臂, and a round collar robe 圆领袍.

The sleeve pertaining to the arm of the dominant hand was removed from the shoulder and tucked under the belt to allow for maximum mobility and comfort while shooting arrows or horse riding.

Left image: modern recreation of Tang Dynasty archery ensemble. Credit for image to @麟趾 on Weibo [image source].

Right image: scene of an ancient polo game from the tomb of Li Yong in Fuping County , Shaanxi province. Credit for image to @彰漢堂 on Weibo. [image source].

The trend created the opportunity for two or more different fabrics to be placed side by side showcasing an aesthetic contrast.

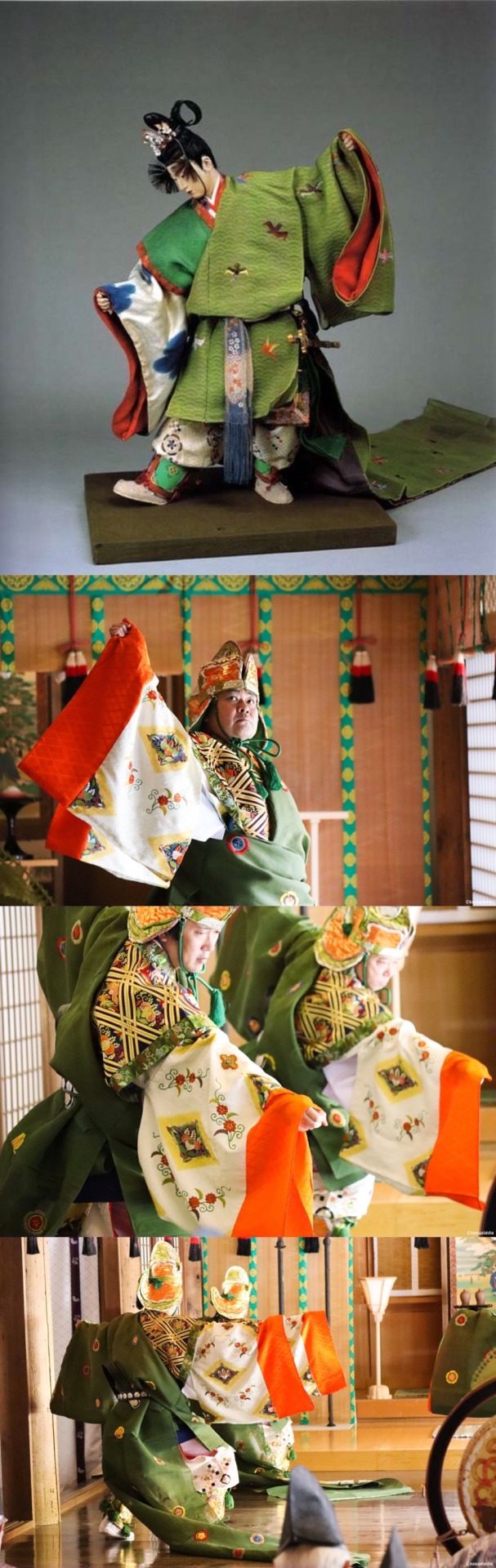

A similar practice & trend emerged in Japan around the same time during the country’s Nara period (710 CE - 794 CE). It’s possible the trend made its way to Japan via Tang influence. Its earliest use may have been as informal wear. By the 11th century CE, it was already well-established in the Japanese court and would inspire other trends in Japanese historical fashion, even a drinking ritual.

Detail of a scene of Illustrated scroll of Kasuga Gongen Kenki Emaki. By Takashina Takakane. 2nd voleme of 20 handscrolls, ink and colour on silk. 40cm height, Kamakura period, dated 1309. Japan Imperial Collection [image source].

When the banbi made its way to Japan, it did so with notable differences. Since Japanese court clothes for both men and women had more layers and fabric compared to Tang hanfu, the banbi (pronounced hanbi in Japanese and written the same way) had to be longer and looser to accommodate the new silhouette.

A better view of the Japanese hanbi. Notice its considerable length. Credits for pictures to @date_bu on Twitter [images source].

The most notable use of the hanbi and the off-sleeve in Japan, however, wasn’t for daily use but for artistic performances where the contrasting layers would be used to their full potential.

Top image: Ikkyoku, from an untitled series of No plays, 1823, Takashima Chiharu, Japanese, 1777-1859, Japan, Color woodblock print, shikishiban, surimono [image source].

Bottom image: Art inspired by Scene from No Dance, Edo period (1615-1868), ca. 1820, Japan, Polychrome woodblock print (surimono); ink and color on paper [image source].

Costume of manzairaku 萬歳楽 dancer. The manzairaku is an auspicious court dance and music performed for the ascension of a Japanese emperor, among other auspicious festivities [image source].

Dancer’s costume of military official [image source].

Young dancers, possibly from the shinto Kasuga-taisha Shrine 春日大社 [image source].

Top image: Sosaku ningyo, “General of cherry blossoms and plums” of Hirata Goyo II, 1936, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo [image source].

Bottom images: dancers in ninwaraku 仁和楽 costumes from the Kasuga-taisha shrine [image source]. Ninwaraku, just like manzairaku, are two type of gagaku 雅楽 (Japanese court music based on Tang court music).

By looking at how cultures influenced one another and how, eventually, they became distinct, we get a richer understanding of the past.

chinese fashion via 国民男友图鉴

#japan#japanese#kimono#japanese court fashion#japanese fashion#japanese traditional dance#heian period#kamakura period#manzairaku#ninwaraku#gagaku#tang dynasty#china#chinese history#hanfu#yuanlingpao#banbi#chinese culture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

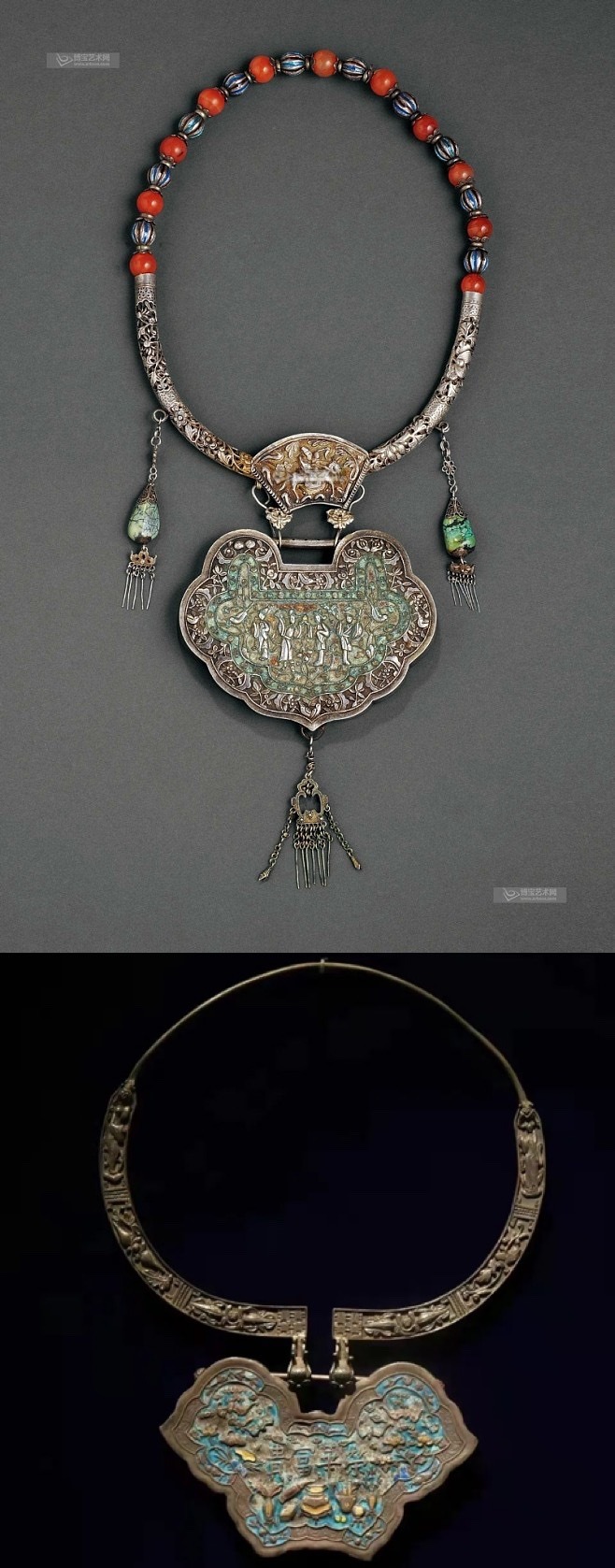

Chinese Longevity Lock -长命锁

Chinese longevity locks were luck charms given to children to protect them from harm, evil, and procure longevity, prosperity, wealth, honor, and good fortune in their adult lives, not dissimilar to a Roman bulla. They were in the shape of ancient padlocks and were linked to a necklace. Most contained messages that could be as general or as specific as the wearer wanted.

As decadent as you could get: rare late Qing Dynasty imperial necklace (ling yue 领约) with double dragons made out of guilt bronze inlaid with gem, enamel, pearl, coral, and linked to a longevity lock made of the same materials [image source].

For boys, some mothers or grandmothers would have them made with messages wishing them luck when they grew old enough to sit the civil service entrance examinations. Eventually, women also started to wear them. They were made out of a variety of materials according to one’s societal class and wealth. The most expensive ones were made out of gold, jade, pearl, enamel, and coral while, the least expensive ones, were made out of silver and brass.

Unknown date; possibly Qing Dynasty. Either gold or guilt silver. [image source]

Not all longevity locks were meant for children and, later on towards the Ming and Qing Dynasties, they were also worn for special occasions such as marriages. Those new locks were designated as “marriage locks”, like in the image below.

Above is a silver marriage lock shaped in the character for double happiness 囍, a popular symbol in Chinese traditional weddings [image source]. The human figures represent the bride and groom.

The predecessor of the longevity lock was the "Longevity thread", which can be traced back to the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD). According to historical records, every household hung silk thread of five colors on the lintel (upper door post) to ward off bad luck during the Dragon Boat Festival (China Daily, 2007).

Qing Dynasty Chinese gilt silver longevity lock [image source].

During the Wei-Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasty period (403 BCE-581 CE), the thread was not only worn during the Dragon Boat Festival but also during Summer Solstice. Eventually, one thread became five different colored ones, braided together, and worn on the wrist. The tradition made its way to the imperial court in the Song Dynasty where male officials also wore the ornament. The emperor used to give them as gifts to the officials on the eve of the Dragon Boat Festival. Gradually, the longevity thread become the longevity lock that we would know throughout the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Read more at China Daily.

Chinese silver cloisonne longevity lock. Unknown period [image source].

The majority of old longevity locks that survive to this day and age come from the Qing dynasty where traditional Chinese jewelry making reached its apex thanks to technological, mining, sourcing, and technical improvements.

Qing Dynasty longevity lock linked to a silver necklace inlaid with kingfisher feathers [image source].

Due to high infant mortality rate, a baby’s birth was only celebrated either 30 days after birth, 100 days, or a full lunar year later. Only then, would a longevity lock be provided. Depending on local customs, only boys would be awarded a longevity lock. At the age of 12, the child would undergo a lock-opening ceremony that changed depending on region and local practices (China Daily, 2007).

Top image: very late Qing Dynasty or possibly early Republic Era guilt silver longevity lock with auspicious symbols engraved [image source].

Bottom image: detail view of engravings in longevity lock [image source].

Longevity locks came in a wide variety of shapes. The ones featured in this post are just two distinct styles out of a myriad of others. Some longevity locks came with grooming tools and resembled a Victorian chatelaine.

Top left corner: late Qing Dynasty (19th century) longevity lock made of silver with traces of gold wash and mythical scenes depicted [image source].

Top right corner: Qing Dynasty silver longevity lock with the traditional Chinese characters 贵富堂满 (it’s read from right to left) calling for wealth and honor. It’s engraved with auspicious animals such as a rooster and dragons [image source].

Bottom: mid Qing Dynasty guilt bronze and enamel longevity lock in the shape of the character for concave 凹. It has the characters 福家全 (read from right to left) engraved on the border calling for good fortune to the family as well as auspicious symbols surrounding it, such as a bat [image source].

Qing Dynasty gilded silver necklace and longevity lock inlaid with kingfisher feathers with the engraved traditional characters 貴富華榮 (read from right to left) calling for prosperity, good fortune, and wealth [image source].

Top picture: very late Qing Dynasty or early Republic Era silver longevity lock for the children of Qing noble officials. Inlaid with agate, turquoise, and other precious stones. Engraved with auspicious symbols, such as magpies [image source].

Bottom picture: Qing Dynasty butterfly-shaped longevity lock with traditional character engravings of 貴富華榮 (read from right to left) calling for good fortune, prosperity, and wealth [image source].

Reference:

#chinese#chinese culture#chinese history#qing dynasty#qing jewelry#chinese traditional jewelry#history#长命锁#longevity lock

205 notes

·

View notes