Text

Taqqiq, the moon spirit [Inuit mythology]

Ever-present in the night sky, the moon plays a central role in countless folktales and myths from around the world. In native Inuit religion, the moon is inhabited by an Inua (supernatural spirit) named Taqqiq, which literally means ‘moon’. This enigmatic but benevolent creature watches over humanity and is responsible for guiding the souls of the dead to the afterlife. He once was a mortal man, and his transformation into the moon spirit is the subject of several different stories. Details differ, but a common version has it that he lusted after his own sister, Siqiniq. According to one tale, he made his advances at night, when it was too dark for her to recognize him. But Siqiniq was clever and smeared her body with black soot. The next morning, she saw Taqqiq’s face was blackened with soot and realized that it had been him. He chased her and she fled into the heavens and turned into the sun spirit.

Taqqiq, still chasing after her, followed his sister into the sky and eventually became the moon spirit, ironically reflecting his sister’s fate. He deeply regrets his actions and tries to make up for them. Perhaps because of this, he is said to sometimes descend to the Earth when women are abused and then saves them. Sometimes, he takes them back with him to the moon, where they live happily as Taqqiq takes care of them.

His outfit is made with gorgeous white fur, and Taqqiq himself is said to be particularly handsome. In some stories, he is said to travel with a troupe of dogs. It is unclear to me where these dogs came from, but they are particularly powerful and large.

The moon spirit is also associated with the hunt: the Polar Inuit believe Taqqiq brought wild animals to the world of the living so that humans could hunt and eat (hunters would sometimes offer prayers to thank him), and in the belief of the Inuit of Baffin Island, these animals are specifically mentioned to be caribou and seals. Iglulik Inuit believe that Taqqiq would bestow good fortune on seal hunters, whereas the people from eastern Greenland believe him to bless whale hunters. Taqqiq is often depicted with his signature whip, which he uses to hit young boys, as it is his role as a spirit to harden them into strong hunters. While this is a harsh (and presumably very traumatic) way to teach a kid a lesson, Taqqiq is regarded as a protector of young boys and defender of the weak.

Source:

Taylor, J. G., 1997, Deconstructing deities: Tuurngatsuak and Tuurngaatsuk in Labrador Inuit Religion, Études Inuit Studies, 21 (1/2), pp. 141-158.

Christopher, N., 2013, The Hidden: a compendium of arctic giants, dwarves, gnomes, trolls, faeries, and other strange beings from Inuit oral history, 191 pp, p. 178-181.

D’Anglure, B. S. and Philibert, J., 1993, The Shaman’s Share, or Inuit Sexual Communism in the Canadian Central Arctic, Anthropologica, Canadian Anthropology Society, 35 (1), pp. 59-103.

(image source: Christopher Stevens, painted for Pivut Magazine, Copyright Inhabit Media)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

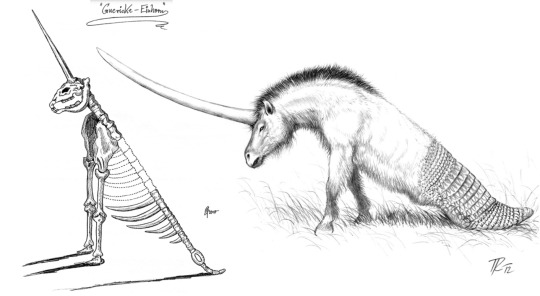

The Magdeburg unicorn [Bad paleontological reconstruction; miscellaneous]

I have a different kind of creature this week, because it's April 1st!

In 1663, quarry workers excavated a bunch of odd skeletons near Quedlinburg, Germany. Otto von Guericke, the mayor of Magdeburg at the time and also a local scientist, identified the reconstructed creature as a ‘unicorn’ in his report in 1678. The creature had a slightly curved horn of 5 ellen (about 2.3m) long. Otto also mentioned that the remains were damaged due to the clumsy removal of the bones by the quarry workers.

In truth, the workers had found the remains of Pleistocene animals, including the front legs of a mammoth, what appears to be a woolly rhinoceros skull and either the tooth of a narwhal or an elephant tusk. The bones are not identified with 100% certainty because the reconstruction became lost to time.

Forty years later, another unicorn horn had been found (this one was actually the tusk of a straight-tusked elephant). Several respected scientists (including Gottfried Leibniz) would eventually confirm that these were indeed the remains of a unicorn. In 1714, Valentine published his somewhat clumsy attempt at a reconstruction of what he believed to be a fossilized unicorn. If palaeontologists or paleobiologists at the time had any theories about the ecology of the creature, they might have been lost to time, as I couldn’t find anything about it. Going by the contemporary illustrations, perhaps the Einhorn might have been assumed to hop around like a kangaroo, or maybe it was a slow walker, dragging its tail behind it.

The Museum für Naturkunde in Magdeberg currently displays the famous model of the reconstruction (a double reconstruction, if you will, for the original reconstruction got lost). Today, the ‘Guericke Einhorn’ is widely used as a textbook example of a bad paleontological reconstruction, though in Guericke’s defense, the mistake wasn’t as obvious back in the 17th century as it is today. Several unusual bones were found closely together and were incorrectly assumed to be part of a singular, puzzling animal, as Guericke obviously didn’t have access to the current knowledge about each of the Einhorn’s component animals.

The Sewecken Hills area actually has a very rich Pleistocene fossil record – the Lampe collection being famously catalogued by Alfred Nehring in 1904 – but at least for the time being, unicorn fossils remain absent from this list.

Sources:

Diedrich, C. G., 2021, Unicorn ‘Holotype’ skeleton from the Late Pleistocene spotted hyena den site Sewecken-Berge (Germany), Acta Zoologica, 104(1), pp.1-70.

Van Kolfschoten, T., 2021, The woolly rhinoceros from Seweckenberge near Quedlinburg (Germany), in: S. Gaudzinski-Windheuser, O. Jöris, The Beef behind all Possible Pasts, pp. 39-48. DOI:10.11588/propylaeum.868.c11306

(image 1: image on the left: a 2011 redrawing by Elke Grönig of Leibnitz’ 1749 illustration. Right: 2012 drawing by George Teichmann based on the famous reconstruction)

(image source 2: Reddit user and_so_forth)

#creatures#miscellaneous#mythical creatures#well not really a mythical creature#but I think it's a great fit for April Fools day!

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

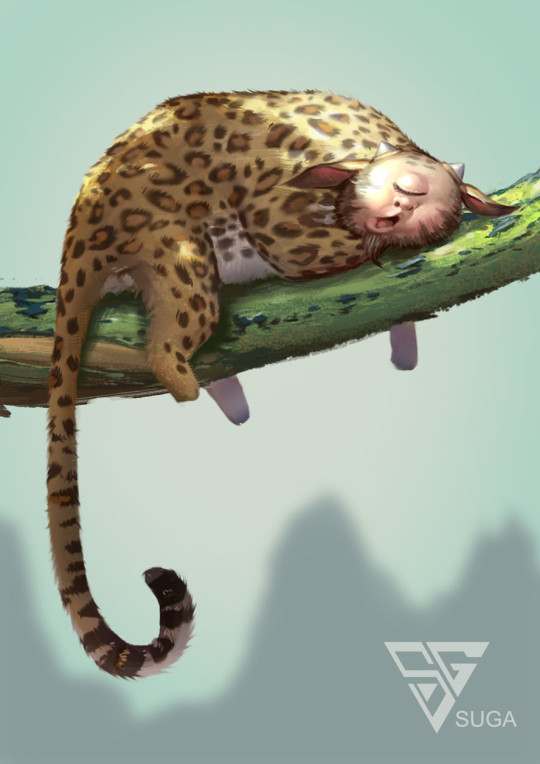

The Zhujian [Chinese mythology]

According to the ancient Chinese Shan Hai Jing (the ‘classic of mountains and seas’), there is a place called Single-Sheet Mountain. The location of this mountain, if it even corresponds to a real-life place, is unclear, but it features a desolated high-altitude landscape where no trees or other plants grow.

Several strange creatures call these heights home, one of which is the Zhujian. The most striking characteristic of this bizarre beasts is its human head, while its body resembles that of a leopard. It has a singular eye in the middle of its face, and its ears resemble those of an ox. The Zhujian has a remarkably long tail, which it holds in its mouth when moving. When the creature sits down, its long tail is coiled.

Not much is known about these creatures, but the Shan Hai Jing also mentions that it is known for making angry shouts.

Source:

Strassberg, R. E., 2002, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange creatures from the Guideways through the Mountains and Seas, 313 pp., p.123-124.

(image source: SUGA良仁 on Artstation)

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

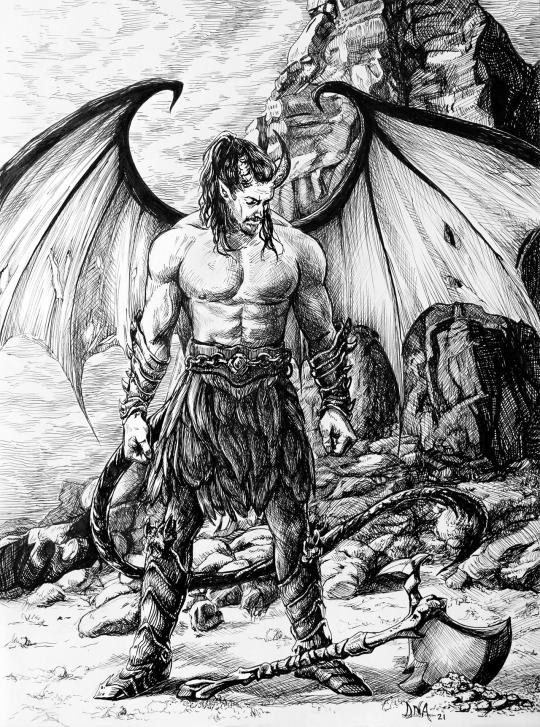

The Cambiones [Christian demonology; medieval European mythology]:

A very common theme throughout mythology and religion that connects stories about mythical creatures of many, if not all, civilizations: where magical monsters and supernatural beings exist, there are stories about people having sex with them.

In some stories, this union between the natural and the unnatural results in a child. There are many medieval European stories about children with one human parent and one fey parent. These stories might have originated as a way to explain physical abnormalities or rare traits in infants, such as an unusual appetite or deformities. For example, Matthaeus Parisiensis (a 13th century English historian) describes a Welsh boy who supposedly was the offspring of a human parent and an Incuba, which is a supernatural creature. The boy had already grown a full set of teeth by the time he was 6 months old, and became weirdly tall when he was a teenager. Because of this, he was classified as a ‘Gigantulus’. Another story tells of a boy named Tydorel, whose fey parentage caused him to be unable to sleep.

This all brings us to the Cambiones (singular: Cambion): the offspring of a human parent and a demon. These creatures resemble human infants but with a monstrous appearance. In addition, they weigh much more than a regular child. One often-cited story (cited by Morasch, 1725, among others) from Galicia (Spain) tells of a female beggar who struggled to cross a river with her child. A rider on horseback saw her and offered to carry her baby across the water, but the horse collapsed under its weight. She then admitted that the baby was not her child, but a Cambion devil which had promised her that as long as she carried it around, people would not refuse to give her alms and money.

In modern pop culture, Cambiones are usually portrayed as classical devils: human-like creatures with horns, red skin and a tail. They also usually grow up like regular people rather than remaining in the form of an infant, and are often the result of a forbidden love between a mortal and some kind of fiend. But looking at older mentions of this creature, the nature of the Cambion actually differs a lot between stories and authors, and it is not always the child of a human and a demon:

According to the account of William of Auvergne, dating from the 13th century, Cambiones are demonic illusions resembling babies who have been left in a human household to replace a kidnapped human infant. The word comes from ‘cambiti’, meaning ‘[those who] have been exchanged’. They are predominantly male, cry much more than a normal child, and possess a voracious appetite, to the point where 4 maids are unable to produce enough milk to satisfy a single Cambion. They remain with their human family for years before mysteriously disappearing.

Nicolaus van Jauer, in his 1405 Tractatus de Superstitionibus, claims that Cambiones are in fact not magical illusions, but real living demons. In his version as well, these creatures had been left in human households by the devil.

Still later, in the 1486 Malleus Maleficarum, Heinrich Kramer posits that there are three kinds of Cambiones: the first type is the offspring of a human man and a Succubus demon. The second kind is created by the devil from a bit of semen he collected from a sleeping human man. And then the third kind is not actually a child, but rather a mature demon who magically takes the form of a mortal infant. All three types of Cambiones distinguish themselves from normal babies by their enormous appetite, and the fact that they never grow, no matter how old they are.

Finally, I want to mention Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, which claims that a Cambion is actually the offspring of two demons: a male Incubus and a female Succubus. They retain most of the traits that the other versions had, though: they eat much more than normal infants and are much heavier. De Plancy recites a story about a Cambion which screamed whenever someone touched him, and laughed when something bad happened nearby. In this version, they only live for seven years.

Sources:

Green, R. F., 2016, Elf Queens and Holy Friars: Fairy Beliefs and the Medieval Church, University of Pennsylvania Press, 285 pp., P. 112-115.

Goodey, C. F. and Stainton, T., 2001, Intellectual disability and the myth of the changeling myth, Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 37(3), p. 223-240.

Morasch, J. A., 1725, Praelectiones academiae ex medicina practica de febribus et capitis morbis, habitae in Alma, Catholica Electorali Universitate Ingolstadiana, et Paucis abhinc annis consensus authoritate inclyti collegii medici per Partes Publicis disputationibus subjectae, nunc in unum digestae volumen, Graffiana, 806 pp., P. 497-498.

De Plancy, C. and Albin, J. S., 1844, Dictionnaire Infernal, ou Recherches et Anecdotes sur les Démons, Third Edition, Paris, France, 605 pp., P. 111.

(image source 1: YaxeMoon on Deviantart)

(image source 2: Andrea Guardino on Artstation)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Embekete [Onge mythology; Andamanese mythology]

In the religion of the Onge people – native to Little Andaman Island in the Indian Ocean – the Embekete are small humanoid supernatural creatures. Despite their diminutive stature, they play a large role in the system of rebirth. In Onge religion, the nature and manner of one’s death determine what happens to the soul: if you die from illness, your spirit will become a malevolent Eaka, a resident of the world directly below ours. Similarly, if you meet your end at sea, your soul will transform into an ocean spirit, and if you kick the bucket while within the confines of a forest, you will transcend to the world above ours and become an Onkoboykwe spirit.

But the Embekete are a special case. The soul of every Onge person who dies from disease will rise from the corpse to become an Eaka spirit, but one day before this happens, a strange creature climbs out of the dead body. This entity, resembling a tiny humanoid creature, is an Embekete. The Embekete will then try to find the shore and jump in the sea. These strange creatures can tirelessly swim enormous distances, and so the Embekete will keep swimming until it reaches the land of the Inene, which is the Onge term for Caucasian people. It will then live among the white-skinned people and will eventually transform into an Inene itself.

The significance of this bizarre system of rebirth is that supposedly, all Caucasian folks are reincarnated Onge people: they were all Onge in their past life. I don't know if people who are neither Onge nor Caucasian are also supposed to be reincarnated Onge. But if they are, the story then implies that since the very first Onge people grew from trees planted by the Onkoboykwe spirits, all human life originated at Little Andaman Island.

The traditional Onge religion is fascinating and refreshingly unique. Unfortunately, the Onge people are nearly extinct as current estimations place their numbers at about a hundred.

Sources:

Ganguly, P., 1975, The Negritos of Little Andaman Island: A Primitive People Facing Extinction, Indian Museum Bulletin, 10(1), pp. 7-27.

Ganguly, P., 1987, Negrito Religions: Negritos of the Andaman Islands, in Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition, Lindsay Jones (editor), Volume 10, pp. 6455-6456.

(image: Onge women engaging in a traditional dance. Image source: Ganguly, P., 1975)

#Onge mythology#spirits#mythical creatures#world mythology#undead creatures#well not technically undead I guess#more like reborn from the corpse of a previous life

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

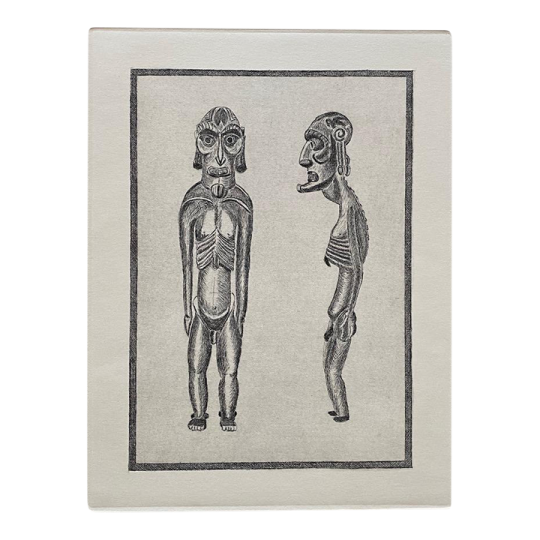

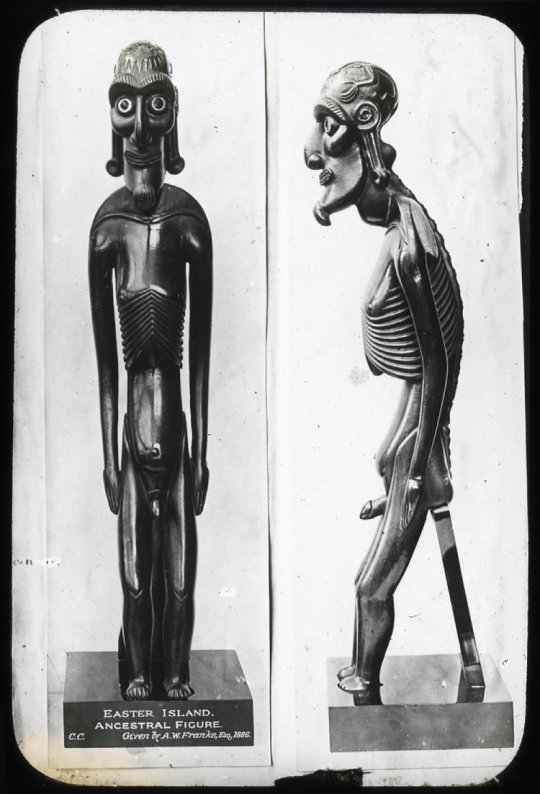

The Aku-Aku [Rapa Nui mythology; Polynesian mythology]

In the mythology of the native Polynesian people of Easter Island, the Aku-Aku are a group of supernatural spirits. They resemble skeletal humanoid creatures but have the ability to disguise themselves as humans.

These beings were the guardians of the land and were fiercely territorial and dangerous. The idea that some parts of land belong to a specific Aku-Aku is still alive today in some parts of Rapa Nui. These were dangerous spirits and more than one islander had been devoured by a hungry Aku-Aku. However, they could be defeated and even killed by mortal warriors. But despite the danger they posed, these beings were not inherently malicious and benevolent Aku-Aku existed as well. For example, if one of these spirits took a liking to you, you might find that all of your chores had magically been done overnight.

Iva-Atua, a term for a shaman-like class of people, were believed to be capable of communication with these spirits.

At least some of the Aku-Aku spirits are believed to have been humans in life who died and became supernatural undead creatures, but as far as I can tell, this doesn’t apply to all of the Aku-Aku. The first of these beings were said to have arrived on Rapa Nui with Hotu Matu’a, the legendary first king of the island, who supposedly came from a landmass to the northwest of the island (which has long since sunk into the ocean). It is a native tradition to mention the names of Aku-Aku before eating a meal, and if you have guests, it is considered good manners to mention their Aku-Aku (the spirits of the region they came from) as well.

There is a story about two Aku-Aku named Hitirau and Nuko te Mangó, who were carelessly sleeping without their human disguise. By pure coincidence, Tu’ukoiho, son of the legendary king Hotu Matu’a, found the two spirits while he was taking a stroll.

(As a small note: Hotu Matu’a and his son were Ariki, a term for a noble ruling class that roughly translates to ‘nobility’ or ‘royalty’. I used the term ‘king’.)

He found it a truly remarkable sight, as these people were sleeping but they did not have any intestines or flesh on their bodies. Clearly these were supernatural beings! Tu’ukoiho decided to leave without disturbing them, and then a third Aku-Aku spirit showed up and awoke the sleeping spirits. ‘Wake up!’ he yelled, ‘for you were not wearing a disguise and now the mortal Ariki has seen your true, miserable bodies!’

Hitirau and Nuko te Mangó were distraught at this news. They quickly got up and, after donning human flesh and blood like mortal people wear clothes, hatched a plan to get out of their situation. The two spirits, now unrecognizable as anything but two normal humans, deduced which way the prince must have gone. They took a shortcut and cut off his path, pretending to be innocent travelers.

‘Well met, oh noble Ariki!’ said one of the spirits. ‘The same good tidings to you, and to your companion over there’, the prince replied politely. ‘Tell us, noble Ariki,’ asked the spirit, ‘have you seen any strange things on your travels today?’ But the prince denied this. ‘Me? I haven’t seen anything weird or unordinary today.’

The spirits said their goodbyes and both parties continued on their path. But they were not fully satisfied and resolved to try again. This time, the prince met a group of four normal human travelers (again, these were magical Aku-Aku in human disguises) and again he was asked about the strange things that he saw on his path that morning. But like the first time, he denied having seen anything particularly weird. The spirits tried a third time, now disguised as a party of ten travelers, but the results were the same.

Tu’ukoiho arrived at his house in Hangapoukura. When night fell, a huge mob of Aku-Aku spirits stealthily approached the building and listened closely for any conversation, but the prince didn’t say a word about the two skeletal spirits he saw that morning. Now finally satisfied that the Ariki had not seen them asleep, and that the whole thing must have been a misunderstanding, the spirits left.

But the Ariki had seen them, and gathered wood and rope. With great skill and patience, the mortal noble fashioned small puppets in the likeness of the skeletal spirits he had seen, and made them into marionettes using the rope. These were the first kavakava moai, a common type of statuette or puppet from Rapa Nui.

Sources:

Sebastian Englert and Te Pou Huke, 2001, Legends of Easter Island, Anthropological Museum of Easter Island, 291 pp., p.103-107, p.288.

Dreckmann, C. Z., 2011, Familia, propiedad y herencia en Rapa Nui, Anales de la Universidad de Chile, No. 2, pp. 165-185.

Williamson, R. W., 1937, Religion and Social Organization in Central Polynesia, California University Press, 340 pp., p. 33-35.

(image source 1: Ricardo Candiani)

(image 2: a now famous statue of an Aku-Aku in the British Museum)

#Rapa Nui mythology#Polynesian mythology#spirits#mythical creatures#undead creatures#world mythology#myths

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kukilialuit [Inuit mythology]

According to Inuit mythology, the frozen landscapes of Canada and Greenland are home to a mysterious and highly dangerous race of monsters. They are called the Kukilialuit, and while that name is often translated as ‘trolls’ or a different common word for monsters, their most defining characteristics are their long and viciously sharp claws, said to be like knives. Literally translated, the name Kukilialuit means something like “those beings with great claws”. Aside from their hands, they have a humanoid body.

Supposedly, the Kukilialuit live inland, far away from the coasts. Despite their monstrous nature, they are intelligent and build huts to survive the winter. Whether these are isolated huts or built together in a society or settlement is unclear.

What we do know is that they are relentless hunters and regularly eat human flesh. After killing a victim, the Kukilialuit carry their prey away and vigorously slice the flesh from their bones until only the skeleton remains. Slingerland and Collard use the story of a Kukilialuit as an example of folktales where lone travelers (or people who get isolated from a group) get picked off by monsters, teaching the audience that traveling by yourself is dangerous in inhospitable environments like the Arctic.

Only a particularly powerful Angakkuq (an Inuit shaman) can escape from these monsters.

Sources:

Christopher, N., 2013, The Hidden: a compendium of arctic giants, dwarves, gnomes, trolls, faeries, and other strange beings from Inuit oral history.

Slingerland, E. and Collard, M., 2011, Creating Consilience: Integrating the Sciences and the Humanities, New Directions in Cognitive Science, Oxford University Press, 472pp., p.634.

(image source 1: Vinod Rams)

(image source 2: Ethan Nicolle)

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Changfu [Chinese mythology]

Foundation Mountain is a – presumably fictional – location mentioned in the ancient Chinese work Shan Hai Jing, the Classic of Mountains and Seas. Strange creatures dwell on the slopes of this mountain, such as a goat with four ears, nine tails and a set of eyes located on its back.

One of these bizarre species is the Changfu, a mythical bird with three heads and six legs. It also has a third wing on its back, but aside from these extra extremities it resembles a normal chicken.

Not much is known about their ecology or behaviour, but its meat has a special characteristic to prevent the eater from sleeping. Those who hunt and consume a Changfu will find themselves unable to sleep.

Source:

Strassberg, R. E., 2002, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange creatures from the Guideways through the Mountains and Seas, 313 pp., p.87-88.

(image source: Behane on Deviantart)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Onkoboykwe [Onge religion; Andamanese mythology]

Little Andaman Island – or Gaubolambe, as it is called by the native Onge people – in the Indian Ocean is the centre of the universe. Above it, 6 layers of worlds exist, and 6 additional worlds exist below the island. Above these 13 worlds is an immaterial void, and below it lies the primordial ocean, Kwatannange, which is filled with turtles (note: I don’t entirely understand the religious significance of the turtles). This is, though a bit oversimplified, the universe of the native Onge religion.

Each of these world layers is inhabited by a kind of spirits. Though they are usually translated as ‘spirits’, it would be more accurate to call them otherworldly beings: they are not human, but they eat, work, reproduce and die of old age, just like humans. Nor are they immaterial or intangible.

The first layer above the island is the world of the Onkoboykwe, which are the most important of these beings. They created the shining disk that we call the sun, and they created the moon and stars as well. Onkoboykwe are considered to be kind and benevolent, and these spirits harbour no ill will towards humanity. Sadly, I found no description on what these beings look like.

It is important to note that in the Onge creation story, humanity descended from the Onkoboykwe: the first inhabitants of Little Andaman Island, Engigegi and his wife, had come from this strange world above ours. They built a house on the island and planted rows of trees. It is from these trees that the first humans grew.

Interestingly, it is said that if a human dies within the confines of a forest, his spirit will ascend to the world of the Onkoboykwe and become one of them. This is because in Onge religion, the circumstances of one’s death would determine what happened to the spirit.

Sources:

Ganguly, P., 1975, The Negritos of Little Andaman Island: A Primitive People Facing Extinction, Indian Museum Bulletin, 10(1), pp. 7-27.

Ganguly, P., 1987, Negrito Religions: Negritos of the Andaman Islands, in Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition, Lindsay Jones (editor), Volume 10, pp. 6455-6456.

(image: native Onge people posing for a photo. I couldn’t find the original image source, sorry.)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ndamathia [Kenyan mythology; African mythology]

The Kikuyu are a somewhat lesser-known ethnic group located mainly in central Kenya. These people have (or had, I am uncertain whether this religion is still being practised) a religious ceremony that was held every few decades and was connected to a creature called the Ndamathia, a creature associated with rainbows. It was the Ndamathia which made rainbows appear in the sky.

This being was a giant aquatic snake-like reptile of incredible length (said to be as long as the rainbows it created). At the end of its enormous tail grew magical hairs that had potent medical properties.

A complicated procedure was required to harvest these hairs, however. First, the creature had to leave the deep rivers in which it lives. This was done by summoning it with a special ceremonial horn, and when the Ndamathia was on land, it was distracted by a beautiful girl. The monster was dangerous, however, and had to be drugged with powerful medicine, which was administered by splashing it on the ground before the girl (which was traditionally done by the same young girl). The reptilian creature would then proceed to lick up the water containing the drug.

In addition, the girl was covered in castor oil (which is made from beans of the castor plant) to make her slippery. The idea was that if the monster tried to grab the girl, she would be too slippery to hold and she would escape from its maw.

The Ndamathia then followed the maiden away from the water, but as it was an incredibly long creature, it took multiple hours of walking before its tail finally left the water. A group of warriors was waiting patiently for this moment and jumped at the tail as soon as it was on land.

Each warrior plucked as many hairs as possible. Even though the Ndamathia was under the influence of medicine, plucking its tail hairs caused it great pain and the creature would become furious. It immediately returned to the water at great speed, so the warriors had to hide after plucking the hairs. When the giant creature arrived, it would find nobody and decided to go back to the depths from which it came.

As the story goes, the girl who acted as bait to lure the creature away from the water would have an important position in Kikuyu society when the ceremony was over, as she was regarded as a heroine. The priests would then slaughter an ewe, a bull and a male goat. They would then proceed to cut the skins of the ewe and the goat into ribbons and dip them in a liquid consisting of the blood mixed with the stomach contents of the slaughtered animals. The hairs of the Ndamathia were tied to these ribbons to make bracelets, which were to be worn by the elders on the ankle and wrist. When this was all done, a giant celebration would be held.

When Christianity established a foothold in the region, the missionaries tried to convince the indigenous people that the Ndamathia was actually their version of the Christian devil, and the creature was villainised. This made an impact on the indigenous folktales that is still visible today: the Kikuyu’s translation of the Bible translates ‘devil’ as ‘Ndamathia’.

Sources:

Hazel, R., 2019, Snakes, People and Spirits, Volume 1: Traditional Eastern Africa in its Broader Context, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 567 pp.

Kenyatta, J., 1978, Facing Mount Kenya: the traditional life of the Gikuyu, African Books Collective, 260 pp.

Karangi, M. M., 2013, The creation of Gikuyu image and identity, in: Revisiting the roots of an Africna shrine: the sacred Mugumo tree: an investigation of the religion and politics of the Gikuyu people in Kenya, p.24 ch.2., Karangi, M.M. (editor), Lambert.

Karanja, J., 2009, The Missionary Movement in Colonial Kenya: the Foundation of Africa Inland Church, Cuvillier Verlag, 227 pp.

(image source: Steven Belledin. The image is card artwork for Magic: the Gathering and depicts an unrelated seamonster, but I chose it because it fits with the description and I rather like the illustration).

#Kenyan mythology#African mythology#aquatic creatures#monsters#mythical creatures#mythology#bestiary

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tangi [Scottish, Shetland folklore]

There are lots of folktales about supernatural horses that live underwater and entice people into mounting them. Once the victim does so, they find themselves unable to dismount and the horse takes its prey underwater to drown them. The most famous of these creatures are the Scottish Kelpie and the Welsh Ceffyl Dŵr, though there are lots of similar aquatic horse monsters from British, Germanic and Scandinavian folktales. They are related and come from the same root story.

In the Shetland Islands, however, there are two such creatures, and while they are undeniably similar, surprisingly they are said to be two distinct kinds of beings that exist in different habitats. The Njuggel (or ‘Shoopiltee’ in Northern Shetland, among other names) resides in lakes and other fresh bodies of water, whereas the Tangi (also Tangie) is a marine monster. Keep in mind however that this distinction is not set in stone (folklore is hardly an exact science, of course) and in some places the Njuggel and the Tangi are considered to be synonyms.

In the Orkney islands of northern Scotland, the Tangie would appear either as an old human covered in seaweed (true to its name, as the name ‘Tangie’ is likely derived from ‘tang’ which is a local term for seaweed) or as an aquatic horse. This Tangie would jump out at unwary travelers, and it took a particular liking to young women, kidnapping them from the banks of the Scottish lakes and dragging them into the depths to be devoured.

In places where the two are said to be separate monsters, the following distinction is usually made: a Njuggel appears as a white or grey horse with a wheel for a tail that drowns its victims in lakes. A Tangi, on the other hand, is black or dark grey and has no wheel. Tangis are shapeshifting creatures and sometimes appear as cows, other animals, or as humans. When taking the form of a human, a Tangi usually chooses to appear as a handsome young man and seeks out girls to seduce and have sex with. Sometimes they go the extra mile and abduct a girl to marry her. Being associated with the sea, they commonly haunt shores but these creatures make their homes in seaside caverns.

Like its cousin the Njuggel, a Tangi is engulfed in a blue flame when galloping at high speed. Sailors sometimes claimed to have seen one of these creatures as a distant blue flash that raced across the shore.

One old account of these creatures also claimed that they have wings and the uncanny ability to locate any object that fell or was thrown into the ocean, regardless of depth. These claims are not backed by any other sources. However, they do have an important trait that sets them apart from Kelpies, Njuggels, Nixen and the like.

Whereas most Kelpie-like monsters are said to make people mount them and then drown their victims, the Tangi does not need to be mounted. It can cast a spell on its victims by galloping in circles around them. When under the influence of the Tangi’s magic, the victim becomes hypnotized and immediately tries to drown themselves, usually by jumping off a cliff into the ocean. Those who survive find themselves in a dazed state which lasts for a few days at most.

They are not invincible however and share the same weaknesses as the Njuggels: they are afraid of fire, can be injured with iron and lose their power if you utter their name. For example, one story tells of a man who encountered a Tangi. The black horse started running in circles around him but he managed to stab it with an iron knife. The creature ran away and disappeared.

Sources:

Teit, J. A., 1918, Water-beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia, The Journal of American Folklore, 31(120), p.180-201.

Lecouteux, C., 2016, Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic.

Monaghan, P., 2004, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, Facts on File Library of Religion and Mythology, 512 pp.

Pérez-Lloréns et al., 2020, Seaweeds in mythology, folklore, poetry and life, Journal of Applied Phycology, 32, 3157-3182.

(image source 1: orig03 on Deviantart. The image actually depicts a black Kelpie, but I figured it’s fine since the Tangi is related and similar)

(image source 2: unknown, sorry)

#Scottish mythology#British mythology#aquatic creatures#monsters#Kelpie#mythical creatures#fey#bestiary

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dard [French folklore]

Supernatural monsters that suck the milk out of cows are surprisingly common throughout European folklore. I suppose it was a way for farmers to explain why a perfectly normal, healthy cow suddenly didn’t give any more milk.

In the Vienne region of France, stories were told of a strange creature called ‘le dard’. According to Desaivre’s 1882 description, this animal was a snake with the head of a cat, a short tail and four legs. A furry mane ran along the creature’s spine.

Though the Dard is not venomous, it can deliver a vicious bite if provoked. In addition, these creatures are known to make a hideous hissing sound. They suck milk from cows' udders.

Curiously, some farmers in the region claimed to recognize the Dard’s likeness in the decorations on the columns of certain churches, though it’s not mentioned which ones.

Source:

Ellenberger, H., 1949, Le monde fantastique dans le folklore de la Vienne, Nouvelle revue des traditions populaires, 1(5), pp. 407-435.

(image source: me, hence the crude pencil drawing. I figured I could probably draw a cat’s head, right? Such is the folly of man!)

#French mythology#monsters#honestly I think I did pretty well#I'm fairly certain people care more about the text than the image anyway#mythical creatures#world mythology

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi. I actually have two questions, so I’ll send them in separate asks so you don’t have to answer all in one.

I’m trying to do some research about lithuanian folklore, particularly shadow/malicious creatures like the Baubas. I found your post about the baubas, but it didn’t have very much information about it. I’m just wondering if you might ever go back and try to find more, or if you exhausted all your resources with the one post.

Basically, am I going to hit a brick wall in my search?

I remember writing that post several years ago, I indeed had trouble finding sources about the Baubas. At the time, I didn't really take this blog very seriously and often used crappy sources (I go back to fix those old posts every now and then).

According to this article, the Baubas are classical bogeymen figures: stories about them are told to children to frighten them and to dissuade them from bad behaviour (as in, don't play near the river or the Baubas will drag you into the water! or, don't eat this or that because the Baubas will take you if you do!). Baubas are supposed to be aquatic monsters and usually make their lair underwater. As such, there are a lot of stories about them dragging children under the water.

The article I linked also admits that there isn't much information available on these monsters, though one consistent characteristic is that they catch and eat kids (presumably, they focus on misbehaving children rather than good ones). The only things the text mentions about their appearance is that Baubas are horribly hideous and that they have iron horns on their heads and their hands end in strange wooden claws.

Interestingly, the text speculates that the Baubas might have been derived from a much older mythical figure, a local deity of shepherds. He was respected and benevolent rather than malicious, but has since degraded into a monstrous bogeyman character. This theory is unproven, though.

Lithuanian folklore has a lot of regional variants of common stories and monsters, though. This is part of the reason why relatively little information about the Baubas survives: many villages and regions have their own regional variant of the Baubas, and those often have different names and characteristics.

I also found the article 'Intimidating, Cruel and Violent Motives of the Traditional Lithuanian Lullabies' by Vita Dzekcioriute (original title: 'Bauginantys, žiaurūs ir smurtiniai motyvai tradicinėse lietuvių lopšinėse') which gives some examples of old nursery rhymes:

"Be silent, be silent! The Baubas is crouching in the corner. With wooden claws, with iron horns. If you do not sleep, he will catch you."

"Be silent, be silent! The Baubas is coming. If you fall asleep, he will not find you. If you wake up, he will put you in his bag with which he carries children away."

Obviously the original Lithuanian versions sound better than my crude translations, but the point of these nursery rhymes is that if the kid stays up past his bedtime, the monster will come for him.

Finally, according to the article 'Scaring of Children in the Traditional Lithuanian Worldview' that you can find here as a pdf file, the Baubas also punish children for lying and for not listening to their parents.

Sorry I couldn't be of more help, I hope these three articles and the information I extracted from them can be somewhat helpful!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Thila [Burkinese mythology; Lobi mythology]

At the dawn of time, the supreme deity Tangba You created the world. Tangba You fashioned the land, the seas, and then the humans to populate the world. But human men lusted after women and soon began fighting one another over the women, and the deity eventually grew tired of this. He was the creator god, after all, and we can assume he had better things to do than solve every petty issue among mortals. So he withdrew from the world of men, never again interfering with mortal affairs. Before leaving, however, Tangba You figured he should leave someone to guide and watch over humanity, so he created the Thila (singular: Thil): a group of semi-divine nature spirits.

This is the creation story of the Lobi people, who live in the north eastern parts of Côte d’Ivoire and south western Burkina Faso. They trace their roots back to Ghana.

The Thila play a very large role in traditional Lobi religion. These spirits are not really gods in the common sense of the word, but they are somewhat similar to the angels of Abrahamic religion (but note that they are sometimes described as ancestor spirits). They offer protection to the people, but also tell them how they should act. Though normally invisible to mortal eyes, these beings take on the form of an animal or a human in the rare event that they do appear before people.

Normally though, a Thil communicates solely through a ‘Thildar’, which is a human diviner in direct contact with the spirits (the societal role of these people can be likened to shamans of some native American traditions). As per the rules of their religion, a Thildar is always male, and usually there are only one or two of these diviners in a community. Each Thildar stands in contact with his own group of Thila spirits, with whom he can communicate during a divination. He then relays the will of the Thila, which includes guidelines and taboos pertaining to all kinds of subjects, including how the people should dress, have sex, hunt animals, etc. Sometimes the spirits demand to hold great feasts or festive events, and sometimes they forbid certain practises. One example is the village of Korhogo (near Gaoua): the people living here stopped sleeping on mats made from millet stem, because a Thil once forbade it. Also noteworthy is that Thila sometimes demand that the Thildar takes up a specific profession, like becoming a smith or a doctor.

This may sound strict to outsiders, but Thila are kind and benevolent spirits. They receive offerings during special occasions such as births and weddings, and bestow rain and childbirth on humanity. Should the people break the taboos that the Thila enforce, however, they can wreak havoc upon a community.

These spirits are believed to reside in special religious wooden sculptures called ‘Bateba’, which are usually housed in shrines dedicated to that specific Thil. This is important, because the act of placing a Bateba on a shrine greatly enhances its spirit’s ability to manifest in this world, allowing it to protect the people against evil (such as evil warlocks). If a Thil wants a shrine, it will tell this to a Thildar, along with specific instructions of where and how the shrine should be built. Within Burkina Faso, the Lobi are actually renowned for their woodworking skills, and as such the Bateba tend to be impressive works of art.

Finally, I want to mention that there are different kinds of Thila spirits, and the distinction is easily visible in their Bateba carvings. Some examples:

Bateba Phula are humanoid figures with a stiff standing pose. They house regular Thila.

Bateba Ti Puo house protective spirits that defend against evil; they feature raised arms.

A Thil Dorka houses a particularly powerful variant of Thila. It is a humanlike statuette with two heads, referencing the spirit’s ability to watch multiple locations at the same time.

Sources:

Asante, M. K. and Mazama, A., 2008, Encyclopedia of African Religions, SAGE Publications, 920 pp.

Peek, P. M., 1991, African Divination Systems: Ways of Knowing, African Systems of Thought, Georgetown University Press, 230 pp., pages 98-99.

Harvey, G., 2014, The Handbook of Contemporary Animism (Acumen Handbooks), Routledge, 544 pp., page 68.

(image source 1: African Arts Gallery, lot 12963)

(image source 2: MutualArt)

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wingwak [Algonquin mythology; Native American mythology]

Sleep-inducing creatures and spirits are somewhat common in myths and tales from around the world, presumably having arisen independently as ways to explain peoples’ need for sleep. In the folklore of the Native American Algonquin people – who live in Canada – this creature takes the form of the Wingwak (alternatively ‘Wingoc’), a small insect-like supernatural being.

Though the Wingwak is a spirit of sleep, it takes the form of a butterfly (though I have also seen them described as flies). Usually they swarm someone in groups of five in order to put that person to sleep.

There is an Algonquin legend about a celestial being who, being aloof and not paying attention, fell through a hole in the heavens and fell down to Earth. Though he was not hurt by the impact, the being was surprised to find that mortal humans sleep. He eventually discovered a man who slept significantly more than the other humans, and around whose head there was a swarm of butterflies. He crafted a bow with arrows and took aim at the insects. His aim was far beyond that of mortals, so he managed to hit some of the insects with an arrow and chased the others away. Thus, the being from the heavens managed to wake the man and proceeded to share his knowledge with the humans. He prophesized that one day, a race of bearded creatures would arrive in this world. When that happens, the people would die off. And later, the arrival of the women of this bearded species will signal ruin for the people. I believe this last part might be a reference to a different story that I did not manage to find.

The Wingwak is also mentioned in a bunch of proverbs: the saying ‘wingwak ondjita manek’ (“there are many wingwak”) means that everyone is currently asleep. ‘Ni nisigok wingwak’ (“[may] the wingwak kill me’) is said when one is very tired.

Sources:

Chamberlain, A. F., 1900, Some Items of Algonkian Folk-Lore, The Journal of American Folklore, 13(51): pp. 271-277.

University of Western Ontario, 1990, Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics, Volumes 15-20, page 35.

Cuoq, J. A., 1886, Lexique de la langue algonquine, J Chapleau & Fils, Oxford University, 446 pp.

(image source: Pinclub Teaser for the Metazoo Cryptid trading card game, illustration by Siobhan Daly)

This is the third or fourth time I looked up images of a very obscure folktale and found artwork from Metazoo cards. Maybe I should check that out. I really suck at trading card games, though.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

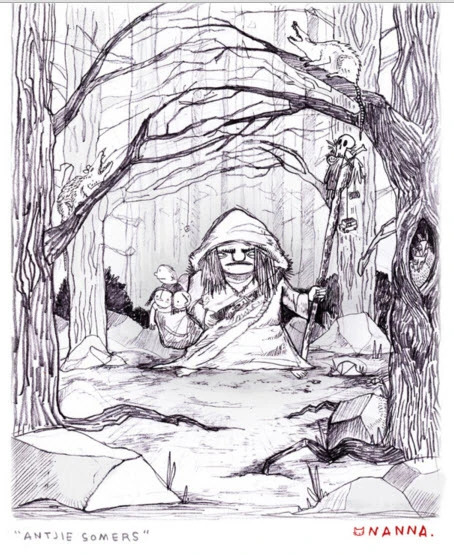

Antjie Somers [South African folklore]

Bogeymen are one of the most common recurring character types among folktales: an evil monster, ghost or undead human that comes out at night and takes misbehaving children. Sometimes to eat them and sometimes just dragging them off to an unknown (yet likely unpleasant) fate. In South Africa, children were told similar tales about Antjie Somers, a local folk character originating from the 19th century. Though she checks all the boxes of a typical bogeyman character, there is one thing that sets her apart from the others: Antjie Somers is human with no clear supernatural traits.

As the story goes, there once was a man named Andries Somers. He worked on a fishing vessel (interesting note: in some variations, he was a slave rather than a conventional fisherman) and was known for his exceptional work ethic: when Andries hauled in his nets, his skill and strength put his fellow fishermen to shame. Aside from being talented and diligent, Andries was also brave and kind-hearted, as he had saved people from drowning on several occasions.

Alas, his diligence bred jealousy in his comrades until one day they decided to teach him a lesson. The fishermen banded together and surrounded Andries on a beach, intending to rough him up. But Andries was a man of exceptional strength and knocked all of his assailants to the ground. When the dust settled however, he saw that one of his attackers couldn’t get up: the man had hit his head falling down and died on the spot. Knowing that he would be charged with murder if he stayed, Andries saw no choice to flee.

He stole a kopdoek (a kind of headscarf) and a dress from his sister and ran away disguised as a woman. After fleeing far away, he eventually found new work in a settlement somewhere over the mountains, where his former comrades would never find him. Andries worked in a vineyard and it wasn’t long until his employer noticed his exceptional work ethic and put him in charge of the other workers. But here his sad past repeated itself, and he soon found himself the target of jealousy and anger from his co-workers. Eventually, they found the dress and kopdoek Andries still kept in his hut, and mocked him endlessly about it. They called him Antjie (a feminine name) and poked fun of him for crossdressing. He endured these childish taunts for three days, before packing his stuff and leaving under the cover of night, full of anger and disappointment.

Andries was never found, but after a while, children who had been sent to the forest to collect lumber started telling stories of a strange elderly woman dressed in a striped dress and kopdoek, wearing a sack over her shoulder. The woman was always angry and would threaten kids with her knife, threatening to kill them and stuff their corpses into her sack. Their parents connected the dots and assumed this mysterious woman to be Antjie Somers, as they had taken to calling Andries. From then on, people would warn their kids to behave, lest Antjie Somers stab them and take them away in her sack.

This story actually has some political context, as it originated in a period of tension between workers and farmers following the then-recent abolishment of the slave trade. I won’t go into the details here, but there is quite a bit of historical context to this tale if you want to read up about it.

Though Antjie/Andries is the protagonist of the story, this character was later demonized further and turned into a demonic monster, a goblin, a monstrous woman with animal-like characteristics or a witch in some retellings. In this last version, Andries quite literally became a woman when he turned evil, which also has some political subtext. In fact, because the character was crossdressing and gender-nonconforming, Antjie Somers is sometimes regarded as a queer character, though I assume this is more of a modern interpretation (he only donned the dress to disguise himself, after all). The moral of the story however remains quite simple: don’t leave children unattended in creepy woods.

Sources:

Steenekamp, M., 2011, Antjie/Andries Somers: Decoding the bodily inscriptions of a South African folklore character, research report submitted to the University of the Witwatersrand in fulfilment of the requirements of the Master’s degree of Arts, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Croeser, C., 2020, A wilting whisper of Antjie Somers: a meditation on the witchery and gender-non-conformance of Afrikaans Folklore Figure Antjie Somers, Scrutiny2, 25(2).

Gorelik, B., 2021, Cross-dresser as a bogey: on the gender ambiguity of Antjie Somers in South African folklore, South African Journal of Cultural History, 35(1).

(image source 1: Anja Venter)

(image source 2: Galago on Deviantart)

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The folktale of the Ketelaars and the haunted castle of Maldegem [Belgian folklore]

The Belgian city of Maldegem used to be plagued by a gang of notorious bandits called the ‘Ketelaars’. The name ‘Ketelaars’ is an old Dutch word for coppersmiths who made and fixed things like kettles for a living, also called ‘Keteileirs’ in older sources. I'm not sure this gang ever really existed because I found no mention of them in actual historical sources, but there is a well-documented folktale about them (which was originally a song, called ‘de legende van het heerke van Maldeghem’ meaning 'the legend of the lord of Maldegem'):

As the story goes, the lord of Maldegem was out hunting one day deep in the woods, when he came upon a shepherd waiting for his sheep to return. This man didn’t look unusual but he did carry a beautiful, well-crafted horn that immediately caught the lord’s attention.

And so the lord dismounted and talked to the shepherd, asking if he could blow that wonderful horn of his. The shepherd protested and refused but the lord was very persistent. Eventually, he grabbed the horn anyway and blew it loudly.

Unfortunately for him, the shepherd was a bandit in disguise: all 36 Ketelaars were hiding nearby and the sound of the shepherd’s horn was the signal for the thieves to gather. The lord of Maldegem was reminded that actions have consequences – even for nobles – and he soon found himself surrounded by the entire gang of robbers. The bandits couldn’t risk their hideout being found, and so they agreed to kill the lord.

But the bandit who had disguised himself as a shepherd disagreed. Perhaps he didn’t like unnecessary bloodshed, or perhaps he was afraid that killing the lord would cause his servants to come looking for him, or maybe he simply took a liking to this odd fellow. Whatever his reason, he argued that they should let the man go and – being a talented orator – he managed to convince the rest of the gang. And so they let the lord go, but they did make him promise to ‘never speak with your mouth of what happened here today, and never write with a pen about it.’

The lord solemnly swore that he would never do either of those things, and he quickly mounted and disappeared. But he couldn’t just let those robbers and thieves go about their business, and so he rode to the city of Brugge with a plan.

When he arrived, the lord demanded a cart full of white sand. He then spilled all of the sand on the floor and spread it into a thin layer, and removed his shoe. Carefully, he wrote his story in the sand with his toe, and the onlookers understood what had happened. Immediately, a group of soldiers travelled to the hideout of the Ketelaar gang. All 36 members were swiftly arrested and sentenced to death by immurement.

The lord of Maldegem did not show mercy and ordered the construction of a subterranean dungeon with 36 chains. All of the robbers were chained to the wall, given a loaf of bread and a can of water, and then the lord’s men closed the last hole in the walls, entombing the criminals forever.

But the spirits of the Ketelaars never found rest, always lamenting their fate and how stupid they were to trust the lord of Maldegem. Unable to truly leave this world, their ghosts haunted the castle of Maldegem.

One day, the building was plagued by a supernaturally terrible storm: the heavens raged and screamed with thunder and lightning. The lord of Maldegem was struck by a lightning bolt and died on the spot. And so, the spirits of the bandits got their revenge.

This is the story as it is told by professor K. C. Peeters. My second source, which in turn cites a book from 1963 that I’ve been unable to locate myself, tells the same story with some minor differences (there, it was the shepherd who blew his horn instead of the lord).

The story of the Ketelaars is claimed to be centuries old but no precise date is given. The oldest mentions that I personally found were from J. F. Willems in 1838 and one from Frans Willems in his 1848 collection of folk songs.

In Reesinghe, Maldegem, there is a castle that’s sometimes implied to be the haunted location in the story but it’s not old enough. East of the current building, however, there are ruins of a much older fortress. I cannot say with certainty that this is where the Ketelaars were imprisoned, but I do know that it has a basement which is now dedicated to bats.

Sources:

Peeters, K. C., 1979, Vlaams Sagenboek, Davidsfonds, Leuven.

Volksverhalenbank

Notteboom, H., 1995, een literair historische benadering van I. Rond den Heerd: de legende van het heerken van Maldeghem, Appeltjes van het Meetjesland: jaarboek van het Heemkundig genootschap van het Meetjesland, nr. 46.

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/58231 for the details on the castle.

Willems, J. F., 1838, Belgisch museum voor de Nederduitsche tael- en letterkunde en de geschiedenis des vaderlands, Deel 2, Belgisch Museum, which you can read here.

(image: the ruins of the supposedly haunted castle of Maldegem. Image source: Willems, J. F., 1838)

24 notes

·

View notes