Niki Lauda & Mike Hawthorn ❤️ Account runner of @Niki.Lauda.Tribute on Instagram @Cazzyf1 on Bluesky and Tiktok

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

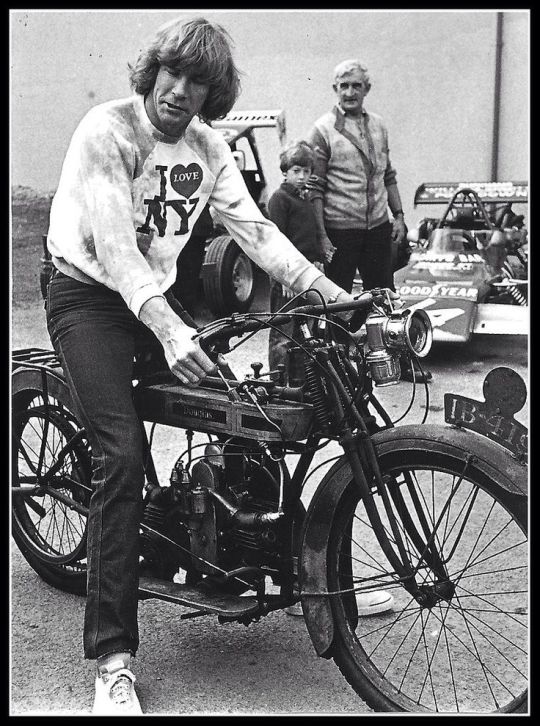

James Hunt on a...motorised vehicle of some sort. Date, location and photographer unknown

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luca Montezemolo, date, location and photographer unknown. Probably at the US Grand Prix in Watkins Glen in 1974, but I am open to correction on that.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Hunt sitting with Robert Fearnall, Tour of Britain Rally, 6 July 1973

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

teammates PATRICK DEPAILLER and JODY SCHECKER during the 1976 FORMULA ONE SEASON

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

LELLA LOMBARDI adjusting her helmet before the 1975 RACE OF CHAMPIONS || photo by BEN MARTIN

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter, Mike and Me by Louise Collins

The Sunday Express, March 1959

THE aircraft bumbled its way through the German sky. Peter, my husband, was dead and Mike Hawthorn and I were flying back to England.

We were silent and both feeling a little teary. Then Mike turned to me and murmured: "Mon ami mate wouldn't like to see us like this"

I was greatful for Mike then. But it was only a few weeks later, when he too was dead and people started to talk to me about him, that I realised what we three had meant to each other.

The start wasn't very suspicious.

It was at Sebring in Florida and I had just married Peter Collins. We bumped into Mike one day and I asked Peter about him.

Peter said: "He's a nice chap." His voice was flat, and he would have shown more enthusiasm for a visit to his dentist.

As for Mike, he gave a facile grin and was gone.

It was of no importance to me at all. I just remembered thinking, Mr Hawthorn would never be one of us.

But how does deep strong friendship grow?

There was no one dramatic incident that bundled us together.

Yet in less than two years I had become a partner in a trio with two blond and brave young men, then suddenly and violently lost both of them for ever.

Looking back now I can see the first tiny straws in the wind that made our friendship.

Both Mike and Peter drove for Ferrari.

Their first distrust of each other as they found themselves on their own with a foreign team melted. Peter, the new boy, spoke fluent Italian. Mike, the old hand, had stumbled along for years with a vocabulary about as large as that of a rather backward budgerigar.

It was out of this business like beginning that their appreciation for each other grew.

And soon our first question when we arrived at an hotel was always: "Has Mike arrived?"

Mike always asked: "Are Louise and Peter here yet?"

Peter and I had a yacht down in Monte Carlo. We stole every chance to be aboard it. As the months went on the image of Mike Hawthorn was with us too. Peter would be on deck and would suddenly shout out for me to come. He would point to a pretty girl walking past on the quay and say: "Wouldn't Mike like to see her?"

Then between us we would hoard all the gossip and all the little incidents so that we could pour them out to Mike next time we met.

You may know nothing about motor racing. You may think it's silly, foolhardy and a waste of time - and trivial occupation in an earnest world. But that doesn't detract one scrap from the brilliance of Mike.

Grand Prix driving is fierce, tough and a dangerous career and at 29 Mike was the master of them all.

That takes qualities few men have. But he had them, and like all champions in any way of life, he walked alone.

He was always lonely.

I am telling you this because I have just read the book he wrote before his death. This is the story of the season that left him a giant towering over the Grand Prix circuits. It should be a proud and arrogant book full of success.

But it is not. It is a simple, almost humble story of his friendship for Peter and me.

To me it is a gift, a diary.

I can't remember the first time I woke up to find Mike in our bedroom looking down on Peter and me and saying: "Where's the tea?" But always after that, whenever we were together we had tea and breakfast in our room.

Peter and Mike were cheerfully bossy. They bullied me. There was never enough tea and while I was ringing for more they would drink up all the milk.

There was pressing to be done and buttons to be sewn. There was no peace for me. And all the time they would be reading an endless succession of mystery stories. They would swap them, discuss them, and when they found a good one they insisted that I read it.

They were remarkably relaxed. Even on the eve of a race they would lounge in our room and read. Only now and again they would get up to go to the circuit for the practising or the race itself.

Then they were like small boys. I am sure they never thought for one moment that people were going to see them. They went there just to watch other drivers.

They did have their little conceits. They would get furious if some official created difficulties about getting tickets or getting onto the circuit. Mike, who never shared his own moods, soon borrowed Peter's. If he came into the room and Peter was upset about something, within minutes Mike would be upset too.

Then they would send me shopping to get the Daily Express. They had to have its Four D Jones comic strip. From that they got their name for each other... mon ami mate. They were always mon ami mate and I was mon ami matess.

It was very light-hearted and childish, but it made us laugh and kept us all calm.

It was a new life for Mike.

For years he had stayed with the noisy gang. Now he was finding a sort of peace. The transition wasn't always easy in odd little ways.

If he met a girl he thought an old married couple like Peter and myself would approve of, he would bring her along to us. But if he thought we wouldn't approve he would take incredible trouble to avoid us.

Peter for all his part was frantically anxious for Mike to be world champion. He buried his own racing interests in his concern for Mike.

But our friendship was a really simple affair.

We had our parties, but often, while the rest of the Grand Prix circus was beating up the town you could find us three sitting over the dinner table, not saying a word, reading detective novels.

It brought us three a very happy happy year.

But Mike's book reveals two incidents that moved me deeply. One hurt me, the other leaves me wondering still.

In his book Mike says Peter and I went off to a wedding in Paris and left him at a loose end. I wish we had known. He could have so easily come too. I regret that one single day that the three of us could have shared but didn't.

The other is when Mike is talking about Peter's death. Despite what is said at the time neither Mike or I was with Peter when he died.

I was told Peter was unhurt and walking back to the pits, so I just stayed where I was. When I discovered the truth, I couldn't get to him in time.

Mike, on the other hand, saw Peter's crash. Soon afterwards, his own car broke down - I suspect with some help of him. But Mike did not turn up to the pits for ages.

When he did come, he was carrying one of Peter's gloves and his crumpled helmet.

He never did tell me where he had been all that time.

In his book he writes a confusing story of not being able to get back from the other side of the circuit. That's nonsense.

I long to know what Mike was doing when he pulled out of the race.

I can believe only that Mike who saw Peter thrown from his car didn't want to face me then. While I went to the hospital, Mike went alone to our room where we had had tea with us that day, and packed our luggage.

Then he arrived at the hospital...too late.

With Peter dead, Mike and I flew home.

Soon afterwards I returned to Monte Carlo. At Nice airport was the little car Peter and I had parked there when we flew too his last race. I drove it alone to our yacht. It was a miserable journey. But I was just trying to play my way back into life.

After a week on the yacht where Peter and I had been so happy I felt much better. And then I got an invitation to go to Monza to see the next Grand Prix. I didn't want to go but Ferrari had some idea that it would be rather like getting back on a horse after a fall.

I brooded about it.

Then went.

I realised that I was still young and it was quite possible that one day I would be invited to a motor race again. So I felt I had better get the shock over.

On the morning of the race I went to Mike's room, and we drank tea.

It was a bitter mistake. It was impossible to recapture the old happy days and there was far too much tension.

After the race I met Mike again. He had resumed his old habit of rushing back to England and home the first moment he could.

We smiled at each other and said we would meet again soon.

We never did.

In a matter of weeks Mike was dead too.

#a DEVISTATING read#Louise you are breaking my heart#their friendship was so beautiful#it's amazing how close they were in this sport#and then found it fell apart...#really interesting that she thinks Mike lied about what he was doing after Peter's crash#it makes me wonder#classic f1#f1#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#mike hawthorn#peter collins#louise collins

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Life of SPEED by Peter Collins

World of Sports, July 1957

NEARLY every motor-sport fan who writes to me wants to be a racing driver. Somebody probably my friend, Stirling Moss, who always looks as if he's taking a quiet ride round Hyde Park-has given them the impression that this driving business is easy.

All right. Suppose you can drive superlatively and are prepared to go tremendously fast. Suppose you have an ear so receptive to an engine's pitch that when something goes wrong you can tell the trouble in an instant. Suppose you have assimilated all the knowledge you can gain from a battery of experienced drivers. You climb into a great Formula 1 racing car, its cockpit tailor-made to your requirements, and away you go to approach the first bend at, say, 100 m.p.h. (160 km.p.h.).

Now, world champion Juan Manuel Fangio has suggested that you take this bend at a certain speed, and Moss has told you the angle of approach he prefers. Collins, if you're lucky, has mentioned a change of gear at a certain point, and Hawthorn has indicated where he would start to use his brakes. You do all these things at the right times.

But Collins's gear-change does not give you Fangio's speed; Hawthorn's braking-point throws you out of Moss's line of approach. Instead of floating round in a beautifully controlled four-wheel drift, you head for the banking in a magnificently uncontrolled straight line.

So what do you do? You drive by instinct, my friend. Only if you can add to your technique this instinctive ability to do the right thing at the right time, plus precision-timing that takes years of experience and hard work to acquire, will you become a racing driver.

What is this instinctive quality? I can't really explain it, but here are two examples of it by the man who probably has more than anyone the world's greatest, Fangio.

First, Le Mans, 1955, that tragic day when Pierre Levegh and his Mercedes burst into flames. Fangio was first through after the crash. Smoke poured across the road Lance Macklin's Austin Healey was spinning wildly in the middle of it parts of the Mercedes were still flying through the air.

But Fangio picked his way through the shambles as delicately as if he were dancing in a crowded ballroom.

Secondly, Monaco, 1957. Momentarily failing brakes had caused Moss to crash into a "chicane," or false corner. I couldn't stop. so my Ferrari went into the back of Stirling's Vanwall. Mike Hawthorn, following, stood on his brakes and skidded his Ferrari into both of us. Fangio was a split-second behind ... but again he drove smoothly through the litter of cars, broken poles and general debris.

You can't learn how to do that sort of thing. None the less, you soon find that race-driving is an art involving, as well as intuition and cool courage, a scientific application of certain principles. So however casual Stirling looks, don't think it's an easy life.

I am lucky, because I do not have to race for a living. Some other drivers are in the same position, but many are not. How many of the people I have heard wish that they could be racing drivers would persist with their desire if they had enough money to be able to choose? I think many would soon be disillusioned about the glamour of the business.

My interest in racing-cars grew from being the son of a garage-proprietor in Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It is not an inherited trait. My family spend all their spare time sailing their ketch in and out of Dartmouth: and I'm the same when I get the chance, because I enjoy all forms of water sport..

Nobody urged me to take up motoring, and I was 18 before I made a start, in 500 c.c. Coopers, in 1949. The following year I won my first event, at a "500" club meeting at Silverstone, and two years later had my worst crash to date, when the Cooper I was driving overturned. I was badly shaken.

Another year or so went by before I graduated to the "big stuff," going from Formula 3 to H.W.M., and also driving Aston Martins in sports-car races. It was in an Aston Martin, in the 1955 Mille Miglia, that I had another narrow escape, one of the rear wheels throwing a tyre-tread when we were belting along at 140 m.p.h. (225 km.p.h.) and a piece of the rubber hitting me on the back of the head. I managed to retain control, but had to retire soon afterwards. That was the year Moss won at a record speed.

But I did have some success that year, winning the Daily Express international race at Silverstone in a Maserati and an international event at Aintree in a B.R.M. In June the following year, I won my first Grand Prix, in Belgium, in a Ferrari; and, after further victories in Monza, Rheims and Sicily, became the second Briton (Moss was the first) to be elected Driver of the Year by the nine-nation Guild of Motoring Writers. So far this year, I have had wins in the Syracuse Grand Prix and the Naples Grand Prix, and one big disappointment: retiring with a broken differential from the Mille Miglia when I was leading more than half-way round.

I have now developed one or two likes and dislikes about racing, chief among these being:

I like Ferrari cars (and Enzo Ferrari, a wonderful man, in particular).

I prefer "natural" racing circuits (such as at Monaco) to artificial ones (such as the con-verted airfield at Silverstone).

I do not like open road racing, chiefly through the danger to the public.

This latter fear is common to many drivers, and applies particularly to the Mille Miglia, the world's sternest test of car and driver. Italy is the centre of world motor-racing-that's one reason why my wife, Louise, and I have decided to make our home in Milan and the Italians are the most incorrigible racing fans I know. Time after time on this long, twisting circuit, one finds oneself approaching what looks like a solid wall of people in the roadway. Only at the last moment do they part to let you through. No driver likes to feel he is endangering the public.

But although there is always a great public outcry when accidents occur, it must be accepted that some crashes are almost unavoidable. You can be the best driver in the world, carry all the lucky charms you want (mine is a gold St. Christopher's medal given to me by my mother), be travelling round a course you have covered a thousand times before, at a safe speed and untroubled by other cars-yet still crash.

A sudden mechanical failure can do it; or split-second lack of concentration. But I would deny the charge of "recklessness" which many people have levelled against racing drivers after recent crashes. A reckless driver would never get round the first lap of a practice run in one piece. And if he did, no team-manager in charge of cars which cost several thousand pounds each, and with a firm's name to uphold, would ever let him drive. Piloting a car at speed is a science of precision that leaves no room for error.

Mechanical failure is something no one can foresee. The car is as perfect as excellent, devoted mechanics can make it; these men will cheerfully spend all night stripping down a car to trace one minor fault discovered during practice. But in a race, its thousand and one parts are subjected to stresses and strains which fully reveal its weaknesses. If the driver is alert to the pitch of the engine, the "carry" of the body, its response to the demands made on it, he can tell whether something is wrong. Like as not, he can also assess what the trouble is, for if it can be corrected at the pits, it saves time to give the mechanics some idea of where to look.

A car is never returned to a race "patched up." It either has to be repaired properly, or not at all. That is why so many are retired from races with what, on the surface, seem to be trivial troubles.

Of course, if something goes suddenly-a tyre-burst or brake-failure there is little you can do except make full use of your skill and ability to bring the car to a halt with the minimum of danger. A driver's concentration can be affected in many ways. Escaping fuel, for example, although quickly spotted by the experienced man, can soon make you hazy; and in this year's Argentina Grand Prix, both Stirling Moss and I suffered from the heat of the sun.

I have mentioned Stirling's relaxed appearance. I give a more intense impression, as I prefer to crouch more over the steering-wheel. Every driver has his peculiarities, and the cockpit items are adjusted to his requirements. The car becomes part of you-I expect you've heard the saying, "A good driver drives with the seat of his pants"-but, however well acquainted you are with the car and course, taking one round the other never becomes an automatic action.

First task of a driver is to master the car; the second to memorise the peculiarities of the course and its surroundings. Every corner has its maximum approachable speed, its ultimate braking-point and its method of approach, according to your ability. A fraction of a second gained at every corner can win you the race, but to gain that fraction you have to know exactly how you are going to take the corner whatever the conditions-and what you are going to meet round the other side. Imagine what this involves in a race like the Mille Miglia, which must have as many corners as it does miles each one different and requiring only a slight misjudgment to put you out of racing for good.

On courses like Le Mans, where one covers the same lap time after time, other factors come into consideration. One has, for example, to take into account the degrees of light and shade thrown on vital parts of the course by the scenery at various times of the day. The shadow of a bank not obvious at 10 a.m. can look suspiciously like the start of a corner at noon. Road-surfaces vary, and are affected differently by dew or rain-showers. It is even necessary to note which types of trees overhang the course, because pine needles, for example, can make a resinous patch on a roadway which you would know all about if you tried to brake on it.

My ambition is the world championship. Many people thought I sacrificed my chance last year when I handed over my Ferrari to Fangio in the September Grand Prix of Europe at Monza. This is not so. To win the championship I had to do the fastest lap as well as win the race, and I was in a pretty hopeless position to accomplish either. All Fangio had to do to retain the championship was finish in the first three, which he did. Nobody forces anybody to hand over their cars in the middle of a race, but the principle is that the team No. I driver has first consideration. You obey the team-manager's instructions at all times, even as to how fast you must travel and what position you are expected to fill.

Ever since I reached the front rank I have made a point of competing only in top-class races. I believe a rest-period is necessary, and I try to relax whenever I can. I like having a good time. Enjoying the good things in life is a necessary counterpart to the strain and nervous exhaustion of a professional racing driver's life.

I think Britain has probably the best team of drivers in the world today. Moss is second only to Fangio, and Hawthorn can hold his own with the best. Among an excellent crop of up-and-coming men, I would pick out particularly Tony Brooks, the young Cheshire dentist. Finishing second to Fangio in the 1957 Monaco race was a great achievement.

I don't think British cars quite match up to their drivers, yet. This, I feel, is not so much the fault of the men who design and promote the cars, nor the mechanics who look after them, as of the people who actually make them. Britain was once proud of its craftsmanship, but I feel that in the racing-car business it has been succeeded too much by "push-button" workmanship that is just not good enough.

Most drivers reach their peak between 27 and 42, but rarely stay on top longer than seven years. I shall be 26 in November, so I look forward to a few more years in the game; though if I do pull off that world title I may be content to retire.

And if I don't? Well, I suppose my happiest memory will be of the French Grand Prix in Rheims in July last year. The first prize was £10,000-one of the highest ever offered and every other driver was laying plans to carry off the tit-bit. I lay low, watched the others burn each other out in a hectic battle for the lead, and then came through to take the prize. It was a great day!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mike Hawthorn - We hardly knew you

#thinking about the fact that Stirling Moss is more remembered than Mike#and when people do they hate him because of le mans#life is so unfair for Mike :(#classic f1#f1#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#mike hawthorn

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Life of SPEED by Peter Collins

World of Sports, July 1957

NEARLY every motor-sport fan who writes to me wants to be a racing driver. Somebody probably my friend, Stirling Moss, who always looks as if he's taking a quiet ride round Hyde Park-has given them the impression that this driving business is easy.

All right. Suppose you can drive superlatively and are prepared to go tremendously fast. Suppose you have an ear so receptive to an engine's pitch that when something goes wrong you can tell the trouble in an instant. Suppose you have assimilated all the knowledge you can gain from a battery of experienced drivers. You climb into a great Formula 1 racing car, its cockpit tailor-made to your requirements, and away you go to approach the first bend at, say, 100 m.p.h. (160 km.p.h.).

Now, world champion Juan Manuel Fangio has suggested that you take this bend at a certain speed, and Moss has told you the angle of approach he prefers. Collins, if you're lucky, has mentioned a change of gear at a certain point, and Hawthorn has indicated where he would start to use his brakes. You do all these things at the right times.

But Collins's gear-change does not give you Fangio's speed; Hawthorn's braking-point throws you out of Moss's line of approach. Instead of floating round in a beautifully controlled four-wheel drift, you head for the banking in a magnificently uncontrolled straight line.

So what do you do? You drive by instinct, my friend. Only if you can add to your technique this instinctive ability to do the right thing at the right time, plus precision-timing that takes years of experience and hard work to acquire, will you become a racing driver.

What is this instinctive quality? I can't really explain it, but here are two examples of it by the man who probably has more than anyone the world's greatest, Fangio.

First, Le Mans, 1955, that tragic day when Pierre Levegh and his Mercedes burst into flames. Fangio was first through after the crash. Smoke poured across the road Lance Macklin's Austin Healey was spinning wildly in the middle of it parts of the Mercedes were still flying through the air.

But Fangio picked his way through the shambles as delicately as if he were dancing in a crowded ballroom.

Secondly, Monaco, 1957. Momentarily failing brakes had caused Moss to crash into a "chicane," or false corner. I couldn't stop. so my Ferrari went into the back of Stirling's Vanwall. Mike Hawthorn, following, stood on his brakes and skidded his Ferrari into both of us. Fangio was a split-second behind ... but again he drove smoothly through the litter of cars, broken poles and general debris.

You can't learn how to do that sort of thing. None the less, you soon find that race-driving is an art involving, as well as intuition and cool courage, a scientific application of certain principles. So however casual Stirling looks, don't think it's an easy life.

I am lucky, because I do not have to race for a living. Some other drivers are in the same position, but many are not. How many of the people I have heard wish that they could be racing drivers would persist with their desire if they had enough money to be able to choose? I think many would soon be disillusioned about the glamour of the business.

My interest in racing-cars grew from being the son of a garage-proprietor in Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It is not an inherited trait. My family spend all their spare time sailing their ketch in and out of Dartmouth: and I'm the same when I get the chance, because I enjoy all forms of water sport..

Nobody urged me to take up motoring, and I was 18 before I made a start, in 500 c.c. Coopers, in 1949. The following year I won my first event, at a "500" club meeting at Silverstone, and two years later had my worst crash to date, when the Cooper I was driving overturned. I was badly shaken.

Another year or so went by before I graduated to the "big stuff," going from Formula 3 to H.W.M., and also driving Aston Martins in sports-car races. It was in an Aston Martin, in the 1955 Mille Miglia, that I had another narrow escape, one of the rear wheels throwing a tyre-tread when we were belting along at 140 m.p.h. (225 km.p.h.) and a piece of the rubber hitting me on the back of the head. I managed to retain control, but had to retire soon afterwards. That was the year Moss won at a record speed.

But I did have some success that year, winning the Daily Express international race at Silverstone in a Maserati and an international event at Aintree in a B.R.M. In June the following year, I won my first Grand Prix, in Belgium, in a Ferrari; and, after further victories in Monza, Rheims and Sicily, became the second Briton (Moss was the first) to be elected Driver of the Year by the nine-nation Guild of Motoring Writers. So far this year, I have had wins in the Syracuse Grand Prix and the Naples Grand Prix, and one big disappointment: retiring with a broken differential from the Mille Miglia when I was leading more than half-way round.

I have now developed one or two likes and dislikes about racing, chief among these being:

I like Ferrari cars (and Enzo Ferrari, a wonderful man, in particular).

I prefer "natural" racing circuits (such as at Monaco) to artificial ones (such as the con-verted airfield at Silverstone).

I do not like open road racing, chiefly through the danger to the public.

This latter fear is common to many drivers, and applies particularly to the Mille Miglia, the world's sternest test of car and driver. Italy is the centre of world motor-racing-that's one reason why my wife, Louise, and I have decided to make our home in Milan and the Italians are the most incorrigible racing fans I know. Time after time on this long, twisting circuit, one finds oneself approaching what looks like a solid wall of people in the roadway. Only at the last moment do they part to let you through. No driver likes to feel he is endangering the public.

But although there is always a great public outcry when accidents occur, it must be accepted that some crashes are almost unavoidable. You can be the best driver in the world, carry all the lucky charms you want (mine is a gold St. Christopher's medal given to me by my mother), be travelling round a course you have covered a thousand times before, at a safe speed and untroubled by other cars-yet still crash.

A sudden mechanical failure can do it; or split-second lack of concentration. But I would deny the charge of "recklessness" which many people have levelled against racing drivers after recent crashes. A reckless driver would never get round the first lap of a practice run in one piece. And if he did, no team-manager in charge of cars which cost several thousand pounds each, and with a firm's name to uphold, would ever let him drive. Piloting a car at speed is a science of precision that leaves no room for error.

Mechanical failure is something no one can foresee. The car is as perfect as excellent, devoted mechanics can make it; these men will cheerfully spend all night stripping down a car to trace one minor fault discovered during practice. But in a race, its thousand and one parts are subjected to stresses and strains which fully reveal its weaknesses. If the driver is alert to the pitch of the engine, the "carry" of the body, its response to the demands made on it, he can tell whether something is wrong. Like as not, he can also assess what the trouble is, for if it can be corrected at the pits, it saves time to give the mechanics some idea of where to look.

A car is never returned to a race "patched up." It either has to be repaired properly, or not at all. That is why so many are retired from races with what, on the surface, seem to be trivial troubles.

Of course, if something goes suddenly-a tyre-burst or brake-failure there is little you can do except make full use of your skill and ability to bring the car to a halt with the minimum of danger. A driver's concentration can be affected in many ways. Escaping fuel, for example, although quickly spotted by the experienced man, can soon make you hazy; and in this year's Argentina Grand Prix, both Stirling Moss and I suffered from the heat of the sun.

I have mentioned Stirling's relaxed appearance. I give a more intense impression, as I prefer to crouch more over the steering-wheel. Every driver has his peculiarities, and the cockpit items are adjusted to his requirements. The car becomes part of you-I expect you've heard the saying, "A good driver drives with the seat of his pants"-but, however well acquainted you are with the car and course, taking one round the other never becomes an automatic action.

First task of a driver is to master the car; the second to memorise the peculiarities of the course and its surroundings. Every corner has its maximum approachable speed, its ultimate braking-point and its method of approach, according to your ability. A fraction of a second gained at every corner can win you the race, but to gain that fraction you have to know exactly how you are going to take the corner whatever the conditions-and what you are going to meet round the other side. Imagine what this involves in a race like the Mille Miglia, which must have as many corners as it does miles each one different and requiring only a slight misjudgment to put you out of racing for good.

On courses like Le Mans, where one covers the same lap time after time, other factors come into consideration. One has, for example, to take into account the degrees of light and shade thrown on vital parts of the course by the scenery at various times of the day. The shadow of a bank not obvious at 10 a.m. can look suspiciously like the start of a corner at noon. Road-surfaces vary, and are affected differently by dew or rain-showers. It is even necessary to note which types of trees overhang the course, because pine needles, for example, can make a resinous patch on a roadway which you would know all about if you tried to brake on it.

My ambition is the world championship. Many people thought I sacrificed my chance last year when I handed over my Ferrari to Fangio in the September Grand Prix of Europe at Monza. This is not so. To win the championship I had to do the fastest lap as well as win the race, and I was in a pretty hopeless position to accomplish either. All Fangio had to do to retain the championship was finish in the first three, which he did. Nobody forces anybody to hand over their cars in the middle of a race, but the principle is that the team No. I driver has first consideration. You obey the team-manager's instructions at all times, even as to how fast you must travel and what position you are expected to fill.

Ever since I reached the front rank I have made a point of competing only in top-class races. I believe a rest-period is necessary, and I try to relax whenever I can. I like having a good time. Enjoying the good things in life is a necessary counterpart to the strain and nervous exhaustion of a professional racing driver's life.

I think Britain has probably the best team of drivers in the world today. Moss is second only to Fangio, and Hawthorn can hold his own with the best. Among an excellent crop of up-and-coming men, I would pick out particularly Tony Brooks, the young Cheshire dentist. Finishing second to Fangio in the 1957 Monaco race was a great achievement.

I don't think British cars quite match up to their drivers, yet. This, I feel, is not so much the fault of the men who design and promote the cars, nor the mechanics who look after them, as of the people who actually make them. Britain was once proud of its craftsmanship, but I feel that in the racing-car business it has been succeeded too much by "push-button" workmanship that is just not good enough.

Most drivers reach their peak between 27 and 42, but rarely stay on top longer than seven years. I shall be 26 in November, so I look forward to a few more years in the game; though if I do pull off that world title I may be content to retire.

And if I don't? Well, I suppose my happiest memory will be of the French Grand Prix in Rheims in July last year. The first prize was £10,000-one of the highest ever offered and every other driver was laying plans to carry off the tit-bit. I lay low, watched the others burn each other out in a hectic battle for the lead, and then came through to take the prize. It was a great day!

#Oh Peter sweetie I love you#such an interesting read#classic f1#f1#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#peter collins

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I learnt about Peter & Louise Collins + Mike Hawthorn from the book "Dear Family"

Stirling Moss once fell asleep on the Collins's snooker table

Peter would take his racing cars down to the local school for the boys to be able to sit in them

Peter was a water boy, any moment he could get he would be on a boat enjoying the sea

Mike, Peter and Louise LOVED reading mystery books. They would consume them rapidly confusing all the other drivers why they were sitting around reading so much

Mike would frequently give lifts in his plane to other drivers including Wolfgang von Trips

Mentioning Wolfgang, everyone HATED the beard he grew

Enzo Ferrari's wife was really fond of Louise Collins and would attach herself to Louise's side even though neither of them could speak to each other

Louise's dad would constantly supply Peter's dad with cigars

Peter Collins loved cats and had some siamese kittens that he would take everywhere

Mike Hawthorn once jumped into a bath Peter and Louise were sharing...naked

Peter's love for motor racing was taken over by his love for Louise

Both Peter and Louise believed Stirling Moss's wedding to Kate was a big publicity stunt

Peter wanted to retire racing to focus on building a life and family with Louise

When Mike and Louise were travelling back after Peter's death they sat in silence until Mike managed to whisper 'Mon ami mate wouldn't liked to have seen us like this'

#im just curious in what sense did the collins believed that stirlings wedding was for publicity#<- in terms of how public is was that there were a couple hundred people and all the press taking videos for the news and tons of photos#though Peter was an usher with how public it was compared to his wedding with Louise where it was all very quick and only a few people there#they saw it as mainly being for publicity when it didn’t need to be

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

When I think of classic F1 relationships that seem as though they may not have been a standard cishet partnership, I feel kind of happy and hopeful that even in more conservative times, people found a way to live their truth and be happy.

I agree entirely, it is always lovely to see and hope they were able to be happy in a society that hated them. Outside of all the speculation about Mike, Peter, and Louise, I think of two drivers from the 50s who we do know were LGBTQ+ and were able to live a life they wanted without too much bother; Raymond May and Shelia Van Damm. It was well known in the community where their attractions lied, and as far as I read, neither of them faced any scrutiny or people reporting them to the police.

I've shared openly information about Mike, Peter and Louise, down to them being one of my main special interests and that I have already shared so much to keep their legacy going, as these times, the 50s seem rarely remembered by F1 aside from the occasional mention of Fangio and Stirling Moss. But there have been other interesting rumours I've happened across about other drivers who might not have had a standard relationship either. As you said, it makes me so happy to know they had the opportunities to live the life they wanted.

#I hope my rambling makes sense#your message is really well said anon#F1 has such a rich history and there is definitely so much under its layers#but I think a lot should also be left covered as the likely wishes of the drivers#classic f1#anon ask#cazzy answers#mike hawthorn#peter collins#louise collins#raymond mays#shelia van damm

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

the more i read about mike hawthorn and the collinses the more i am convinced that was a polyamorous relationship

You and me both, they essentially lived with each other at the tracks, travelled together, ate together, bathed together so it seems 😂 one day I am convinced information will come out about it

I mean this image I think says enough on its own

#anon ask#cazzy answers#the threesome we all need#classic f1#mike hawthorn#peter collins#louise collins

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I learnt about Peter & Louise Collins + Mike Hawthorn from the book "Dear Family"

Stirling Moss once fell asleep on the Collins's snooker table

Peter would take his racing cars down to the local school for the boys to be able to sit in them

Peter was a water boy, any moment he could get he would be on a boat enjoying the sea

Mike, Peter and Louise LOVED reading mystery books. They would consume them rapidly confusing all the other drivers why they were sitting around reading so much

Mike would frequently give lifts in his plane to other drivers including Wolfgang von Trips

Mentioning Wolfgang, everyone HATED the beard he grew

Enzo Ferrari's wife was really fond of Louise Collins and would attach herself to Louise's side even though neither of them could speak to each other

Louise's dad would constantly supply Peter's dad with cigars

Peter Collins loved cats and had some siamese kittens that he would take everywhere

Mike Hawthorn once jumped into a bath Peter and Louise were sharing...naked

Peter's love for motor racing was taken over by his love for Louise

Both Peter and Louise believed Stirling Moss's wedding to Kate was a big publicity stunt

Peter wanted to retire racing to focus on building a life and family with Louise

When Mike and Louise were travelling back after Peter's death they sat in silence until Mike managed to whisper 'Mon ami mate wouldn't liked to have seen us like this'

#never getting over them#classic f1#f1#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#mike hawthorn#peter collins#louise collins

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just so you guys don't think I am going crazy

Okay so when I wrote about the time Mike Hawthorn got into the bath Louise had ran for Peter Collins in my dissertation I got the criticism that it came off a bit suggestive of homosexual undertones SO TELL ME WHY READING MY NEW BOOK LOUISE COLLINS REVEALS SHE HAD ORIGINALLY LIED AND THE TRUTH WAS THAT MIKE HAWTHORN GOT INTO THE BATH NAKED WHILE BOTH HER AND PETER WERE ALREADY IN THE BATH

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so when I wrote about the time Mike Hawthorn got into the bath Louise had ran for Peter Collins in my dissertation I got the criticism that it came off a bit suggestive of homosexual undertones SO TELL ME WHY READING MY NEW BOOK LOUISE COLLINS REVEALS SHE HAD ORIGINALLY LIED AND THE TRUTH WAS THAT MIKE HAWTHORN GOT INTO THE BATH NAKED WHILE BOTH HER AND PETER WERE ALREADY IN THE BATH

#Dissertation tutor I submit the plea that it isn't even suggestive anymore#lucky Louise Collins my god#I'm sitting here in the living room with my grandparents trying not to die rn#classic f1#f1#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#mike hawthorn#peter collins#louise collins

39 notes

·

View notes