My personal recollection of the 2016 U.S Presidential Election, November 9th 2016.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Critical Reflection:

The United States 2016 Presidential Campaign was a tumultuous and abrasive affair, repudiating existing political norms and traditions at every turn. It was, without a doubt, the most closely followed and analysed cultural event of the year. The election of Donald Trump on November 8th, 2016, symbolised a changing America; a country increasingly willing to embrace populism and anti-establishment rhetoric. Prosthetic memory is a concept proposed by memory-studies scholar Alison Landsberg in her article “Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner. Landsberg explains prosthetic memory in her article, saying “by prosthetic memories I mean memories which do not come from a person’s lived experience in any strict sense.” (175). Modern technologies such as film, television and social media can transport individuals through time and space, allowing an individual to have a memory of a narrative experience which occurred, without actually having physically experienced those events in any way. Social media played a predominant and at times, contentious role in the lead up to the 2016 Presidential Election. Social media, in particular, allowed me to suture myself to a cultural and political event that I could not actively participate in. Social Media’s accessibility and interactivity, not seen in traditional news platforms, gave users the ability to share, comment or post below candidates advertisements or policy announcements. Social media allowed me to possess vivid memories of experiences that were not my own. I have vivid memories of watching Hillary Clinton’s concession speech, glued to the television. This is however, very unlikely, as her speech would have been broadcast in the very early hours of the morning in New Zealand. Mass technologies, particularly social media and television, have allowed me to take on prosthetic memories of a traumatic event for which I was not physically present. Taking on these “prosthetic memories” facilitated a strengthening in my identification with certain groups in society. In the wake of Trump’s victory, I felt closer to my female friends, my friends from ethnicities different than my own and I also felt a greater kinship to the LGBTQ community of which I was part of. Landsberg further argues in her article that acquiring prosthetic memories can “enable identity formation” (17). Following the election, I was deeply troubled by the state of politics in America. Consequently, I became increasingly politically active in New Zealand and applied to study Politics and International Relations at University. This links to Landsberg’s idea that modern mass-technologies have produced the capacity to cultivate shared social frameworks and spaces for people who “inhabit different social spaces, practices and beliefs” My extensive use of social media and television during the course of 2016 U.S election campaign fostered a greater sense of empathy for marginalized and disenfranchised groups in society, and enabled me to better understand their frequently agonizing histories. My creative project incorporated images of tweets and messages sent on the day of the election. The 2016 Presidential Election exemplified social media as a powerful locale for where the public cultural memory could flourish. My creative project showed social media as a cultivator of prosthetic memories, a type of memory that emerges only at the convergence of a person and a historical narrative or event. The convergence I am outlining means that individuals do not simply apprehend a historical narrative, but have a more deeply felt and personalised experience with the event at hand through a prosthetic memory, though he or she did not necessarily live this experience themselves. As a result of mass-technologies, my friends and I felt as though we were part of a larger history, even if we were living in New Zealand at the time.

Reference List:

Alison Landsberg, “Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner,” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Ebodiment, (London: Sage, 1995), 17- 175.

Celia Lury, Prosthetic Culture: Photography, Memory and Identity, (London and New York: Routledge, 1998), 7.

0 notes

Text

The Day That Was: Recalling the horror of the 2016 U.S Presidential Election.

It was approximately 7:30am when I awoke on the morning of November 9th, 2016. It was an important day, one I had been waiting on for many many months. I was a mix of nervousness and excitement. It was supposed to be the coda to a long, divisive and brutal presidential campaign. A new era of American politics was to surely be ushered in, or so we thought. November 8th or (the 9th in New Zealand) means wildly different things for different people. For supporters of Republican candidate Donald. J. Trump, his win was to be a sort of deliverance, their ceaseless faith in the controversial businessman rewarded after months of polls showing his campaign would fail miserably. In contrast, supporters of Hillary Clinton’s campaign were left confused and shattered. I fit into the latter category. I despised Trump and wanted him defeated terribly as I believed he had unearthed something insipid in the American psyche. I personally was not too fond of Hillary, but I still understood that the choice was unmistakably clear. On the morning of election day, I straddled conflicting feelings of hope and fear. The numbing feeling that maybe, just maybe he could win, never ceased to escape me. It was all that anyone at school could talk about. There was not much learning going on that day, and morning tea and lunch-time discussions inevitably turned to the upcoming election. I was quietly hopeful, arguing with a few avid Trump supporters that were annoyingly vocal at my all-boys Catholic high-school. I had faith in statistics and numbers and had always been a man that trusted polls.

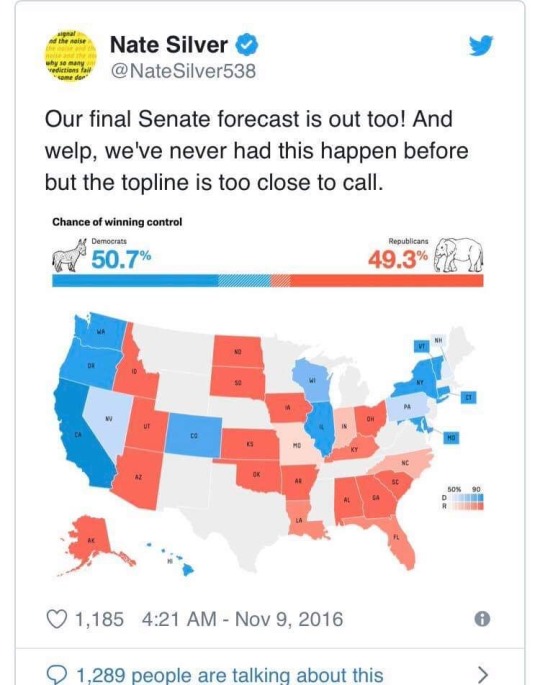

(A tweet by renowned American Statistician, Nate Silver, showing that the Democrats would retake the senate)

Most of my morning was spent reading endless articles theorising on what the potential outcome of the election would be. There were articles on “Which celebrities will leave the U.S if Trump is elected” which I found amusing and strangely reassuring. Other tweets I distinctly remember include images of Hillary Clinton casting her vote in Chappaqua, NY or an image of Vice Presidential Candidate Mike Pence and his family casting their respective votes in Indianapolis, IN. The image that is forever seared into my brain from that day, however, is the picture of Donald Trump peering over onto his wife Melania’s ballot. For me, this picture exemplified Donald Trump’s distrust of women and blatant misogyny. What a dick, I thought, whilst scrolling through a seemingly endless barrage of political commentary and theory. At around 12.00pm in New Zealand, I remember the first results began pouring in. I was stuck in Computer Science class (my least favourite) The benefit of this was, of course, the computer which I used extensively to analyse the first results. My teacher, who already disliked me due to my incompetence with coding, caught me a few times and scolded me. The friend I was sitting next to in class kept peering over at my screen and asking questions. CNN’s bright red logo filling up my twitter feed is something I remember all too well.

(Results begin to pour in from Early Voting states: Vermont, Indiana and Kentucky)

Just past 1.00pm in New Zealand, it was lunch-time at school, and we all watched with bated breath, glued to our phones and laptops. The statistics began to turn against Clinton, whose original chance of winning levelled out at 98%. The number had now fallen to 78% and reports soon flooded in of Trump’s success in rural and ex-urban counties and regions. It was at this very moment that I began reckoning with the possibility of a Trump presidency. The numbers began to sour with every passing minute and soon enough I had lost faith in the statistics I had once trusted so very much. I recall form-time as a period of uncertainty. Reports began to show Trump’s unexpected success in several swing states — states crucial to winning the electoral college. By the end of the school day, I rushed home hurriedly and turned CNN on the television. Pundits were suggesting that the election was a toss-up or too close to call. The entire experience felt incrementally surreal and dream-like.

This cannot be happening, I thought to myself. I realised I had been naïve and had greatly underestimated the power of the Trump message. I realised American voters had chosen personality and populism over qualifications, plans and experience. My once squeaky clean view of America had been tarnished. His success appeared symptomatic of something much darker.

(An image showing Trump’s victory in the crucial swing-state of Ohio)

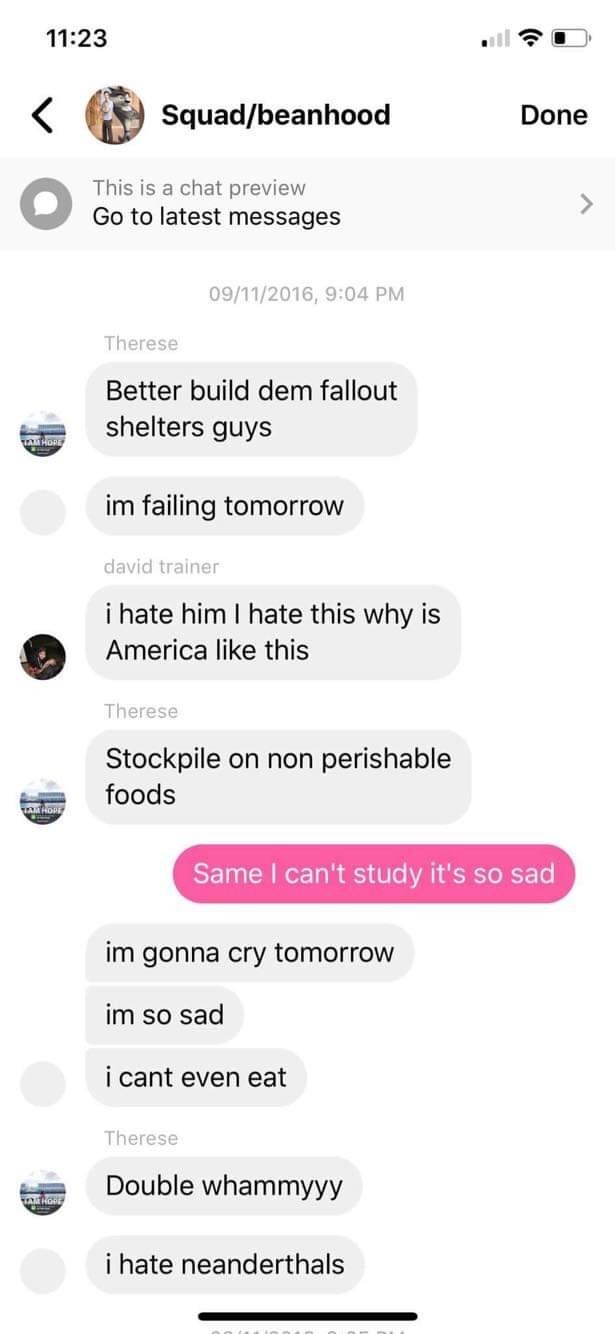

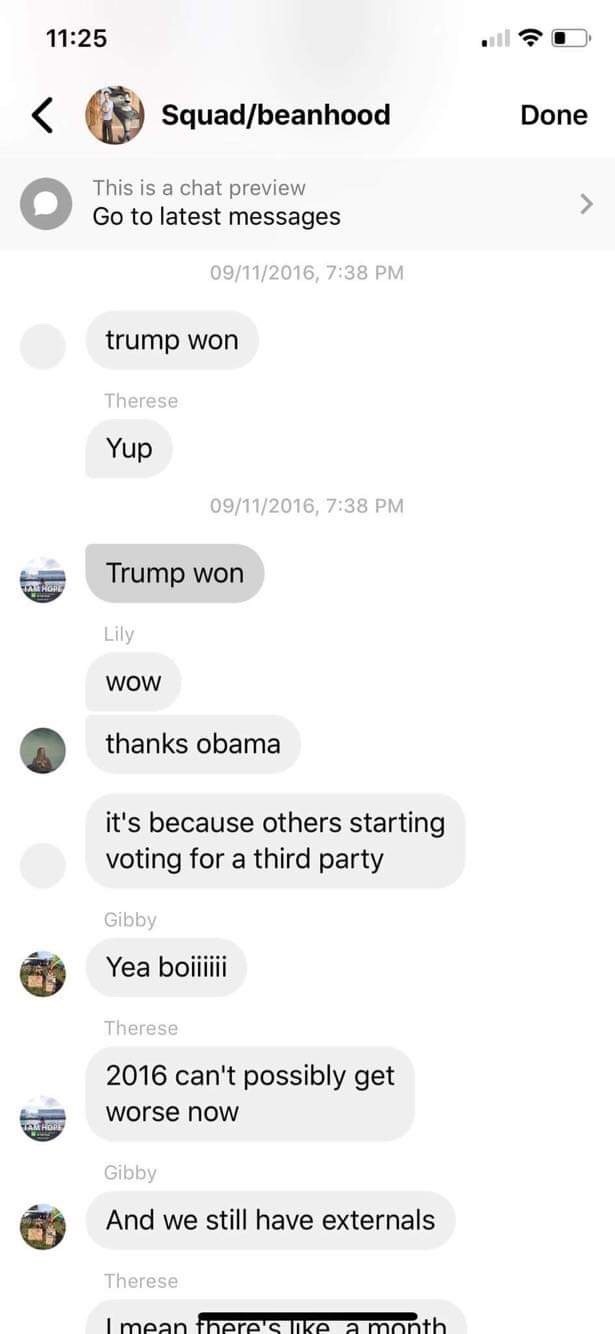

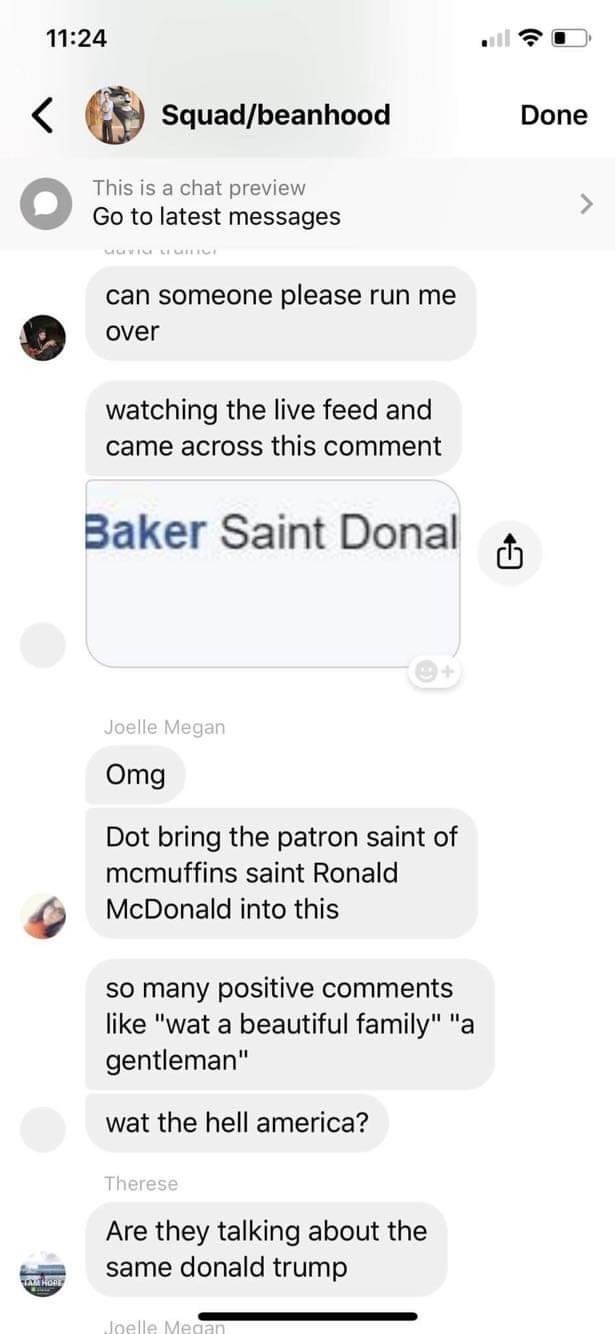

Later that night, my Aunt visited and we watched the unfolding horror live on Television. The graphs that pervaded social media almost seemed to mock me and wink at my credulity. Something on social media had never troubled me as much as seeing those graphs showing the possibility of a Trump Win at ‘95%’ At the same time, several Facebook Messenger group chats I was part of were unusually active. The messages that my friends were sending were characterised by a confusing mixture of anguish, disgust and humour. I have included a few screenshots of these group chats as I believe they are quite telling to the sombre, unexpected and upsetting nature of election day.

(Images taken from a few of my group chats with friends during the time where Trump looked poised to win the Presidency)

The election was so widely anticipated that in the wake of Clinton’s lose, some of my friends were too upset to even study for their exams or eat. The result felt catasphrophically upsetting. These messages show the ubiquitousness of the coverage on the election, and how easily it pervaded our everyday lives. Trump’s win created so much horror for a lot of people I knew. By 9.00pm that night, I remember a close friend streaming live on Facebook and discussing the election with an anger I did not know she was capable of. It was at that moment, as she broke down live on social media, that I understood how greatly Hillary’s loss had affected some people. I felt completely lost for the rest of that night, unable to sleep and paralysed with fear. I thought of my female friends who were forced to watch a candidate win the Presidency after flagrantly boasting about sexual assault. I thought of the LGBTQ community, a community that had already been through enough and now had to watch a man hold up the Pride flag with a smile painted across his face, a flag of which he had no business holding. And, finally, I thought of the many immigrants at my school, in my community and in my city, who had to see a man ascend to the highest office in America after using race and natioality as a tool to fire up voters. It all made me rather sick.

(Hillary Clinton concedes the Election to Donald Trump and apologises to the American people for losing the election.)

(Far-right internet talk show host Bill Mitchell celebrates Trump’s victory.)

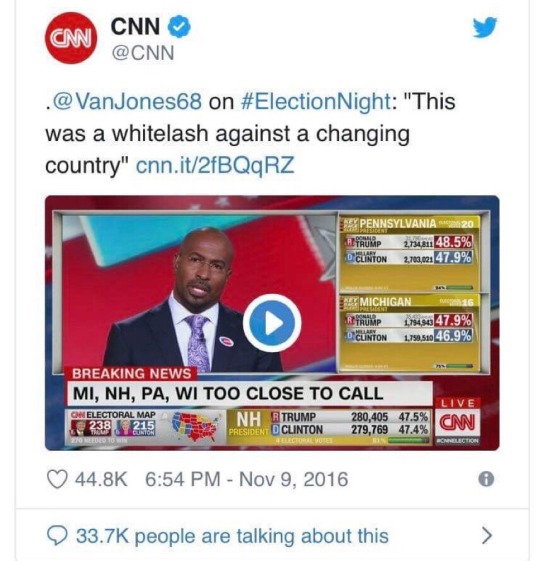

(CNN commentator Van Jones argues that Trump’s win was due to backlash from white-middle class voters who felt left out and dissatisfied with government)

When I look back on the day of the 2016 United States Presidential Election almost three years on, it is easy to forget that I was not actually in America at the time of the election. The pervasive omnipresence of social media and mass-media allowed New Zealanders to believe, for just one day, that we were part of a humongous cultural and political event that could change the course of world history forever. As far as my personal experiences go, it felt as if I my well-being were at stake and in a sense it was. When I look back, I think more of the things I saw online and on Television rather than who I saw or where I was, which is quite telling to how cultural events may be experienced by individuals.

By Cormac Jelicich.

1 note

·

View note