Photo

I have a confession to make. I sometimes have a real problem when I'm working with the museum collection. It's the guilty pleasure I often refer to as "Postcard Voyeurism." Working with a collection of over 3000 postcards, many of them scrawled on, distraction from the loopy handwriting from 100 years ago can get me into a real postcard reading vortex. There could be worse problems, and reading people's notes gives such a perfect glimpse into what people were saying to each other at the turn of the century. While the vast majority of the written postcards say the typical "wish you were here," or "having a swell time," in this post, I'll highlight some of my favorite, more puzzling, entertaining postcards in our collection.

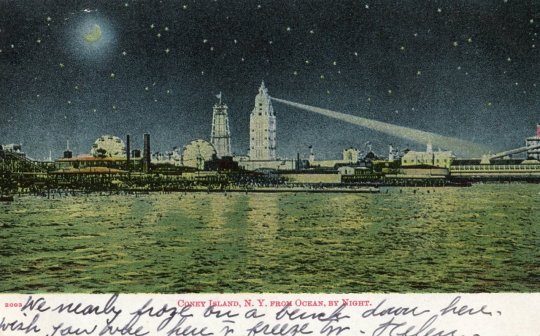

The inscription reads: We nearly froze on a bench down here. Wish you were here to freeze too. Helen. postmarked 1907

Postcards became an extremely popular method of correspondence after an act of Congress legalized the mailing of postal cards on May 19, 1898. Postcards could be sent with a 1 penny stamp, and offered a cheaper way to send a letter. At Coney Island and other destinations, picture postcards acted as inexpensive souvenirs. Below is another favorite: one part of a multi-card poem.

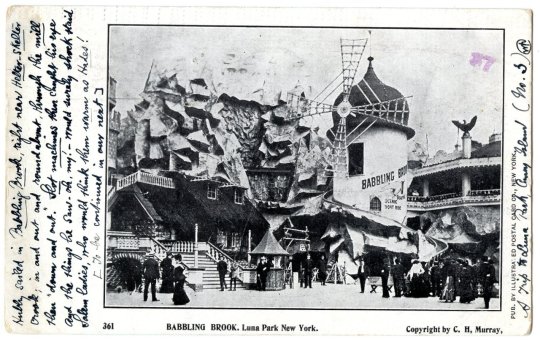

Hubby sailed in Babbling Brook, right near Helter-Skelter crook; in and out and round about, through the mill then 'down and out.' Slot machines then caught his eye and the things he saw - oh, my! - would surely shock staid Salem ladies who would them warm as Hades! [to be continued in my next] A Trip to Luna Park, Coney Island (no. 3), Postmarked 1903

I love this card so much, and really wish we had the other cards with the rest of the poem.

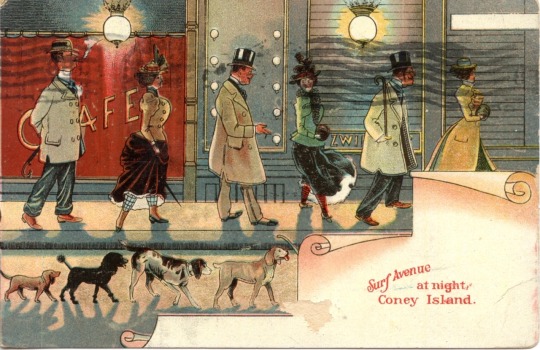

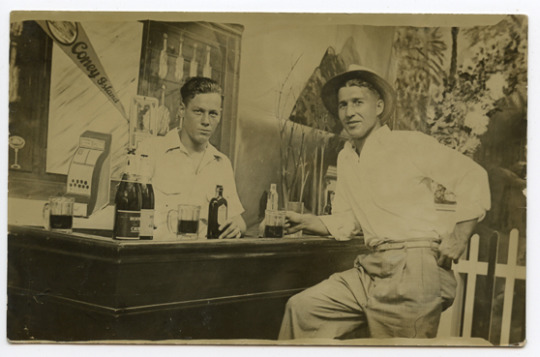

Here is another that really gives a good sense of the kind of fun people were having in Coney Island. This one is a little bit more suggestive of the drinking, partying and carousing popular in Coney Island, and would have probably been slightly scandalous in 1909.

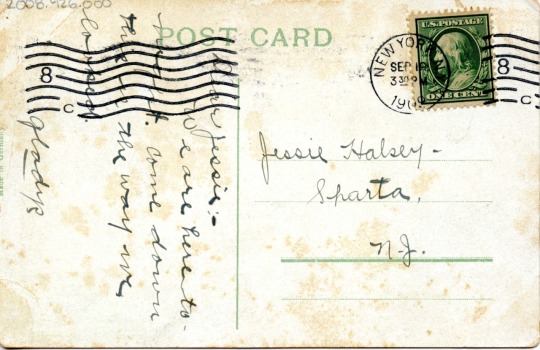

Dear Jessie - We are here to-night. Come down. This is the way we looked. Gladys. Postmarked 1909

The postcards I find most interesting are the ones that are used for practical correspondence, whether asking a favor, updating someone on what's going on in their lives, or conveying important information. One of my favorite postcards in our whole collection (currently unscanned) states: Grandma told me to let you know Uncle Clark died this morning the funeral is 2 o'clock Monday, Ruth. It is a matter of cost and efficiency that would prompt someone to announce a death on a birds-eye view of Coney Island? Another postcard asks if someone would be willing to let space in a barn to store unsold hay. Here's another:

My dear Mallie, Hope you all got home all right. I am feeling some better today, but still have the pains but gone out to my side. Lovely and cook, am using eye wash. Love to both. Postmarked, 1908.

The above is a perfect example of why my postcard voyeurism lives on. Eyewash? Why would anyone put that in a postcard? (other than my own delight) I can practically hear the voice of an old lady complaining about her ailments! I will periodically share future postcards. Until then, I'll keep reading them.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

image via, The San Francisco Call, Mar. 1, 1903

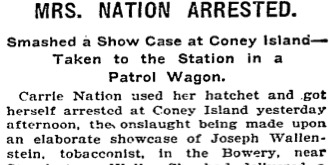

After researching a bit about Raines Law for a previous post, it is clear that very little was effective in preventing people in Coney Island from drinking. In September 1901, the infamous hatchet-weilding temperance leader, Carrie Nation, paid a visit to Coney Island to cause some trouble. Coney Island's debauched reputation made it a natural target for Carrie Nation's hatchet, but surprisingly, Steeplechase Owner, George C. Tilyou was the one who brought her there!

Carrie Nation (also spelled Carry) began a branch of the Women's Christian Temperance Union in her hometown in Kansas, but quickly became dissatisfied with the results of the passive hymn singing outside taverns. In 1899, Carrie's signature "smashings" began, first with piles of rocks, then with a hatchet. She would storm into taverns, brandishing her hatchet and a bible, pour beer onto the floor, clear bars of beer with a single swipe and hack away at anything she could break. She considered her "hatchetations" to be the work of god, and referred to herself as "a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn't like." For this, she was arrested over 30 times in under 10 years.

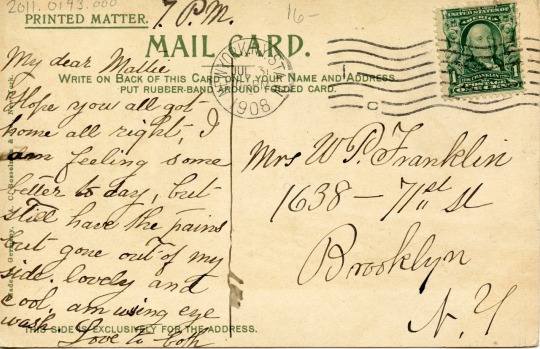

New York Times, Sept. 3, 1901

To me, the biggest question is why would Tilyou, a showman who benefited from the consumption of alcohol in Coney Island, invite someone like Carrie Nation to speak at Steeplechase in the first place? Upon further investigation, the invitation had all the markings of a publicity stunt. It seemed that Tilyou expected a mocking crowd, and promoted the event with talkers, hatchet-selling souvenir venders and people walking around dressed as Kansas farmers.

New York Times, Sept. 3, 1901

The trouble didn't even start with her arrival at Coney Island. She boarded a steam ship to Coney Island and confiscated the cigars of several men (one of them sleeping) and threw them overboard. She went to the bar and dumped as many beers she could onto the floor, and ran after a waiter who narrowly missed her attempts to knock the tray out of his hands. At her actual lecture, despite the crowds that gathered to get a glimpse of her, only about 100 paying customers entered to hear her speak. During her lecture she said "Coney Island would not be what it is if it were not for the government of New York. But what can you expect from a lot of beer-besmeared, nicotine-faced, beak-nosed devils."

She did not leave Coney Island without getting arrested. She marched into a tobacco shop and smashed everything she could with her hatchet. Police came to arrest her, and after throwing a police wagon driver to the ground and resisting arrest, she was handcuffed (for the first time ever) and brought to the Coney Island police station. According to her memoir, when she refused to enter a cell with other women, a police officer struck her, breaking a bone. She was bailed out by George C. Tilyou, himself.

This seems to be an awful lot of trouble to stir up some publicity in Coney Island, but very little could be done to dampen the spirits of visitors in Coney Island's heyday.

4 notes

·

View notes

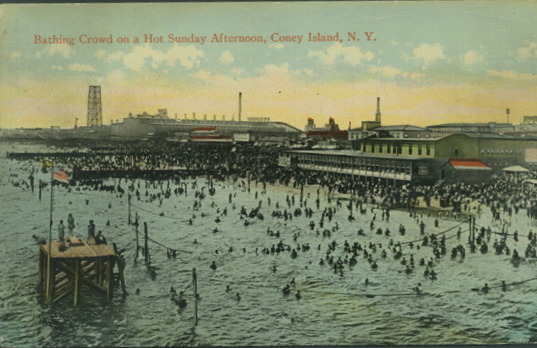

Photo

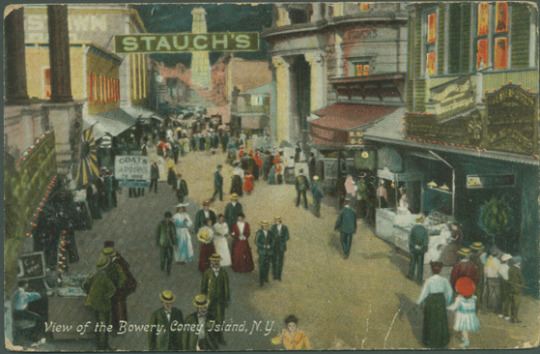

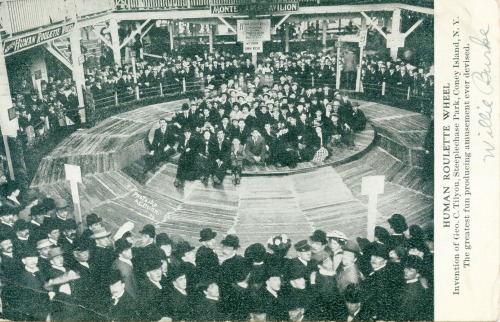

1909 Postcard, Collection of Coney Island Museum

While attempting to sit and write another article about Coney Island history, I can’t help but think of more recent history – the status of Coney Island one year ago. Yesterday was the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Sandy, which devastated the whole area.

On October 29th, I sat in my apartment with some non-perishable food and a battery-powered lantern, overlooking the Hudson River, as the wind kicked up and the water began to get rougher. I had no doubt that the storm would live up to the violence the weather channel was predicting – they’re usually wrong about these things. At worst, I figured we would temporarily lose power and some trees would fall and that would be it. I worried about Coney Island from afar, but figured that the water would predictably rise and recede as it had in previous years, sparing our old building.

As the night went on, things got scarier. The wind got very strong, my house (built in the 1830s) began to sway, the glass in my sliding doors began to flex and I started to panic. Just before I lost power, I saw a photo of Surf Avenue completely under water. Soon after, I watched the beloved houseboat, just steps from my door begin to sink. Despite what was happening in my own neighborhood, I spent the whole night worrying about my coworkers and friends who stayed to move buckets in the museum, in case the roof leaked, their safety, and their homes.

In the morning I texted a coworker to see how everyone was and got a two word response: total devastation. Thankfully, everyone was safe, but it did not look good. The massive clean-up job began immediately. Volunteers showed up. People delivered food and water. It took a while before I was actually able to get down there, due to gas shortages and closed roads, but once I did, I found it hard to believe the “we will rebuild” sentiments that were being repeated. It was terrible. Somehow, we did reopen this past spring.

I guess I wanted to just use this as an opportunity to reflect, and congratulate my coworkers for an incredible job well done. Without their dedication, hours and hours of hard work over many months, and that of volunteers all over, it never would have happened. When I first started there 4 ½ years ago, I had no idea what I was getting into. Coney Island is an astoundingly close-knit, passionate, dedicated community that I am honored to be a part of.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

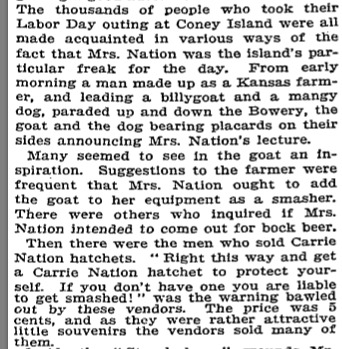

Since its beginnings, Coney Island has been criticized its sometimes-perceived scandalous activities and amusements. During the first decades of the 20th century, Coney Island was full of taverns, gambling, prostitution, girlie shows, dance halls and all sorts of entertainment frowned-upon by the more conservative powers that be. Robert Moses, even famously referred to Coney Island as “tawdry.” Despite all that, it was still a popular destination, frequented by families from all over New York City. Several attempts have been made over the years to clean up the “less moral” activities at Coney Island, often with clever and hilarious workarounds by Coney Island business owners.

On March 23, 1896, the New York State Legislature passed the controversial Raines Law, banning the sale and consumption of alcohol on Sundays and shuttering dance halls. Tavern owners and visitors were appropriately upset, as a six-day work week left Sundays as the only full days for entertainment. At first, bars, saloons and dance halls in Coney Island stayed open, sometimes opening a side door, openly ignoring the new law. Eventually, the law began to be enforced, with police conspicuously arresting bar owners.

The most interesting things about the Raines Law were the loopholes that were found to prevent arrest. The only businesses that were allowed to serve alcohol were hotels, provided that they had at least 10 rooms and served food. “Raines Hotels” popped up all over the city and at Coney Island, sometimes creating the illusion of operating rooms, or subdividing very small spaces into tiny hotel rooms. The unintended consequence of this probably upset the censors more. Prostitution abounded and unmarried couples took advantage of the privacy these tiny rooms offered.

New York Times, April 4, 1902

Even odder were the use of “property sandwiches.” There was great discussion about what actually constituted a meal. In the April 13, 1896 New York Times, Assistant District Attorney, William A. Miles declared “a cracker was a subterfuge, but a sandwich was a meal.” Drinkers were required to pay for a sandwich with their drinks. They were not required to actually eat the sandwiches, they merely had to sit on the table. The same sandwich, sometimes a brick between two pieces of stale bread, or a completely fabricated, unbreakable sandwich, was brought to the table and taken away over and over for each drink and from one customer to the next.

New York Times, January 14, 1907

By 1907, the fake sandwiches were done away with. All food ordered in order to drink on Sundays, had to be actual sandwiches to be eaten. One article (below) describes how bar patrons have come to regard individual fake sandwiches as treasures – with some having customers initials carved into its surface.

New York Times, January 14, 1907

Later attempts to make Coney Island more wholesome included an attempt at closing all amusements that were not strictly educational. In response, L.A. Thompson temporarily renamed Luna Park “The Luna Park Institute of Sciences.” Performers in the Bowery theaters would show to work randomly wearing the same modest clothing, and spontaneously bursting into performance. Rides were also mockingly renamed. Some amusement operators wore caps and gowns and called themselves professors of their particular sections of the “Institute.”

New York Times, May 24, 1909

These laws were eventually overshadowed by Prohibition, yet blue laws still exist in many places today, including nearby Bergan County, NJ, though I doubt such brilliantly silly, typically Coney Island workarounds are still in use.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo via Library of Congress

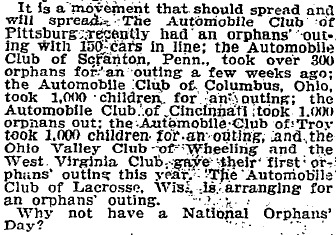

A while ago, I came across this image on the Library of Congress website and thought about what the circumstances were that brought them there. What could it have been like for a kid, living in an orphanage to have an outing with thousands of other kids in similar situations?

The Orphan’s Day Outings began as The Orphan’s Automobile Day in 1904 as a way to create a little levity in the lives of children living in homes for orphans. The idea began with William J. Morgan, a philanthropist and correspondent for Automobile Magazine.

Photo via Library of Congress

The kids were driven in a parade through the city, eventually ending in Coney Island, where they were given lunch, and free, unlimited access to rides and shows. There were even “smile contests,” where the children displaying the biggest measured smiles won prizes. The events were huge successes, with the first events bringing over 1000 children to the parks, and as many as 6,000 in later years. The cars were loaned by car owners, taxi drivers, and truck owners, sometime at considerable expense from lost wages, in order to bring as many children as possible to the events.

New York Times, June 6, 1912

The idea caught on with several Automobile Associations, including AAA, spreading the event to cities and amusement parks throughout the country. Mr. Morgan was given the title of “Father of Orphan’s Day,” for his endless campaigns to create a National Orphan’s Day. Later outings to Coney Island were sponsored by the New York Anchor Police Club, which continued at least until the 1950s.

New York Times, June 13, 1909

Frequently, when preparing these articles, I begin my research looking at one topic, and end up someplace else entirely. This topic got me thinking about my great grandfather and his connection to Coney Island. I knew very little of his time in Cone Island. I knew he lived there from the time he moved to New York from Italy in 1900, but the only story I knew was of his involvement in an accident with some fireworks on the 4th of July, which cost him 3 fingers. I knew that when he was 12, his father died and his step-mother sent him and his brother to an orphanage in Westchester. I wonder if he was one of those children paraded into Coney Island on Orphan’s Day. He always talked about his first time riding in a car, and I wonder if the Orphan’s Day of 1912 or 13 was his second ride.

0 notes

Text

4-Wheeled Ponies at Coney Island

For well over a century, Coney Island performers and entertainers have been attempting spectacularly dangerous feats for audiences - from high-wire stunts and aerial acts, to lion training, to daredevil motorcycle feats, to sword swallowing. Only recently, did I hear of a spectator sport that became popular in Coney Island around 1912 - Auto Polo!

Auto Polo in Coney Island, c. 1913 (image via)

Auto Polo was officially invented by Topeka auto dealer, Ralph "Pappy" Hankinson. It was developed as a fun way to promote the sales of Model T Fords, by demonstrating that they were the fastest, most maneuverable cars on the market. Like equestrian polo, players aimed to score goals by hitting a ball with a mallet, but in auto polo, the use of a regulation basketball made the ball bounce erratically. The game was played with two players per car - one driver and one mallet man. The first games involved 4 cars on each team, but due to the danger were later cut to one car per team.

The game was predictably dangerous. The cars were stripped to almost nothing, and were basically engines on wheels. While the drivers were strapped in, the mallet wielders were not. They rode clinging to a brace while trying to hit the ball, and were constantly thrown from the cars. Later, iron bars extended above the drivers, though they added little safety. Rollovers were very common, and collisions constant.

Film from "Where's the Ball," via

As much fun as this would be to watch, because of safety concerns, I doubt Auto Polo could survive today.

2 notes

·

View notes

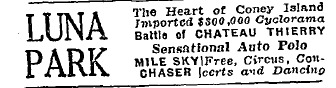

Photo

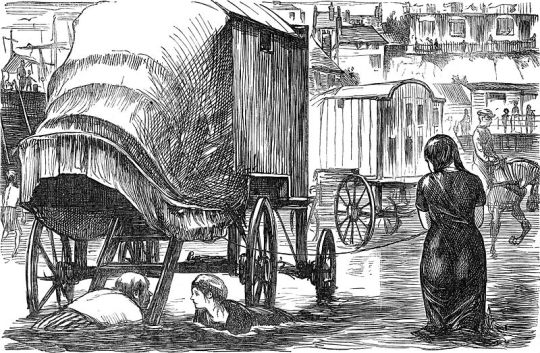

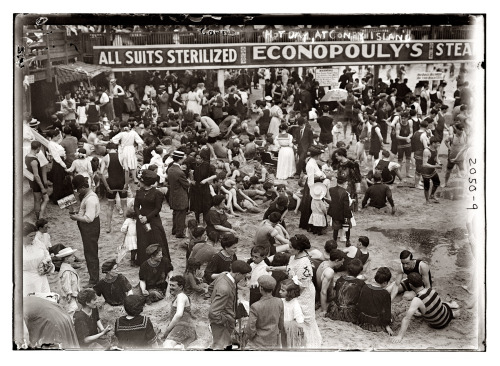

On a hot day like today, it is almost impossible to not think of the beach. Coney Island was well populated during the late 1800s and early 1900s as a place where anyone - no matter how rich or poor - could cool off by taking a dip in the ocean.

Dozens of bath houses accommodated the millions of bathers that came to Coney Island every year, by renting lockers, chairs, and the very modest wool bathing suits often depicted in iconic photos of the time. Women's bathing suits, in order to meet the Victorian decency standards were head to toe, with dresses, stockings, slippers and hats. Additionally, early on, the bath houses and beaches were sex segregated.

While looking for topic ideas earlier today, I came across this:

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 16, 1873.

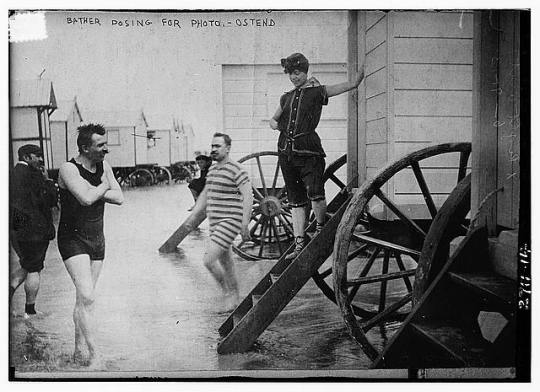

Bathing Machines?? What are bathing machines??

image via Library of Congress

It turns out that to some people, the head-to-toe bathing suits and sex-segregated beaches were not private enough. Bathing machines were essentially dressing rooms on wheels. The bather would get into it in the back, fully clothed. She would undress, change into her bathing suit, and when the operator estimated that the bather was fully changed, it would be led either by horse, or by human-power, into the water. The bather could then slip into the water by way of a step ladder coming from the front door. This way, she wouldn't have to indecently walk from a conventional dressing room to the water.

Punch, October, 1, 1870

They became popular in the 19th century in England, and Queen Victoria reportedly had her very own. Various modifications were made to the design, including bathing machines that were raised and lowered by mechanical means, and some with hoods, so that the occupant wouldn't be seen at all getting in or out of the water. They eventually fell out of popularity when the beaches were no longer sex segregated. Regardless, it is a strange little piece of Coney Island and bathing history.

0 notes

Photo

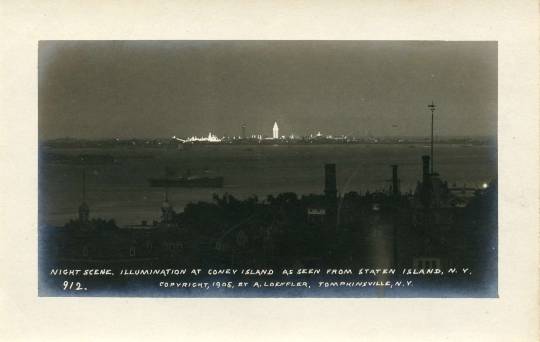

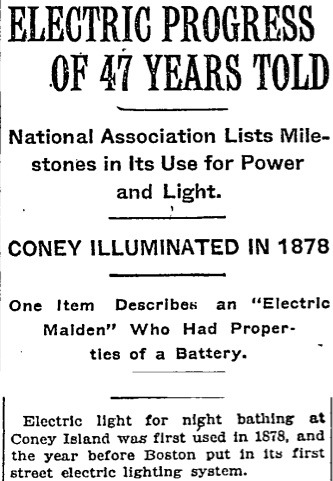

Many people think of light and electricity when they think of old Coney Island. Thomas Edison famously electrocuted Topsy the Elephant at Coney Island, in 1903, during his AC vs DC current rivalry with George Westinghouse. (A terrible sight, which can be viewed through the Mutoscope at the Coney Island Museum). The illumination of Coney Island at night around the turn of the century, was a notable sight. The lights were so bright that they could be seen 4 miles out to sea. I have had several Brooklyn-born friends tell me their parents used to exclaim "turn off the lights! It looks like Luna Park in here!" Visitors would come from all over to see the "The Electric Eden."

A somewhat more surprising electric attraction that predated all three major parks at Coney Island was the practice of "Electric Bathing." The New York Times article (below) claims that Coney Island was first illuminated in 1878 (though by the pre-incandescent arc lamps), the very same year that Joseph Swan created the first incandescent light bulb, and Thomas Edison founded the Edison Electric Company. Lights were placed high on poles on the beach, in the water and on piers to light the water, and allow visitors to continue their fun into the night.

New York Times, September 7, 1924

In an article entitled "The Progress of the Electric Light," dated August 8, 1880, the New York Times refers to electric light as the only thing that will appease "those lunatics that persist in bathing after nightfall." This seems particularly dangerous, with modesty customs dictating that bathers wear full-length bathing costumes, the limited light these lamps offered, and the fact that water and electricity pose a serious electrocution hazard.

Scribner's Monthly, July 1880

The fact that Coney Island's illumination and the very popular electric bathing predated even the first Edison Electric power plant in New York City, and the adoption of the incandescent lightbulb, to me, is nothing short of astonishing. I can only imagine the wonder of people arriving at Coney Island for the first time and witnessing the glow of the lights.

#coneyisland#electricity#electricbathing#electriceden#thomasedison#westinghouse#topsy#amusements#history

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When most people think of old roller coasters, they usually think of something that looks like the above image - twisting and full of drops and peaks that give riders that thrilling stomach-in-throat feeling. (The coaster above was the Tornado.) It is no surprise that Coney Island had a large hand in the development and evolution of the roller coaster, but I didn't know that there was a precursor to these iconic gravity-fueled rides practically in my back yard!

Image via Poor William's Almanack

L.A. Thompson's Scenic Railway was built in Coney Island in 1884 and was powered by gravity. Riders would climb into the seats, and ride down an incline up to another hill, where they would turn around and return to the beginning. This model lead to roller coasters of all kinds, including the Flip-Flap Railway (1895) of Sea Lion Park, and the Loop-the-Loop (1901).

Loop-the-Loop, circa 1903 (image via)

While working with the local history collection at the public library (the non-Coney Island part of my life), I came across mention of the Dunderburg Spiral Railway. This sounded vaguely roller coaster related! After looking into it, I discovered that anyone visiting the Hudson Valley can visit the remnants of an early roller coaster-related railroad that significantly predated L.A. Thompson's Coney Island railways!

Modern sketched map of the Dunderberg Spiral Railway (image via)

The Dunderberg Spiral Railway was preceeded by the Mauch Chunk Railway of Jim Thorpe, PA, which was built originally for mine use in the 1870s. The Mauch Chunk became a popular tourist attraction. In 1889 the Dunderberg Spiral Railway Corporation intended to build a hotel at the top of Dunderberg Mountain. Visitors accessed the hotel by steam railway, and would leave by way of the spiral railway. Looping down the mountain, through tunnels and offering views of the hudson valley, the gravity-only powered spiral railway was to cover about 12 miles and reach a speed of 50-60 miles per hour.

Mauch Chunk Railway (image via)

Unfortunately, the Dunderberg Spiral Railway was never completed. Around 1891, the project ran out of money and construction stopped completely. Interested hikers can visit the site and find handmade tunnels, cleared paths and remnants of the early roller coaster intended to be hotel transportation.

One of the tunnels from the remnants of the spiral railway (image via)

I plan to take a hike once it gets warmer. For more information about the trails, visit the New York New Jersey Trail Conference.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the many ways that Coney Island has left a long-lasting stamp in American popular culture is in song. It has inspired songwriters for well over a century, and continues to do so. More recent songs include at least three very different songs titled "Coney Island Baby," by Lou Reed, Tom Waits, and The Excellents, "Coney Island" by Death Cab for Cutie, "Coney Island Shuffle," by Andrew Bird's Bowl of Fire and many many others.

We have a fair number of leaflets of sheet music and old records of songs about Coney Island in the museum collection. At the time I started working here, I had not heard any of them, and we had no means for playing the records. The elaborate covers of the sheet music were especially interesting as art objects. At the time, sheet music was promoted as "in the style of" or "as popularized by" various performers.

Probably the best known of these old songs is "Meet Me To-night in Dreamland," written by Beth Slater Whitson and Leo Friedman, and published in 1909. It was performed by many, including a young Judy Garland in the 1949 movie In the Good Old Summertime.

Here is a 1910 recording, by Henry Burr, of the same song, digitized from an Edison wax cylinder.

Now, thanks to massive audio preservation projects, like the Internet Archive, and the Library of Congress's National Jukebox, many historical recordings have been digitized and made available to the public. While I understand the mechanics or early recording and playback, for me, it is still nothing short of magic to hear these early recordings.

Another less popular recording is "Meet Me Down At Luna Lena," composed by Henry Frantzen. Below is a 1905 recording by the Haydn Quartet, with Billy Murray as the lead vocalist. To hear it, click here.

It seems that many of the early songs written about Coney Island involved innocent, and not-so-innocent trysts at the beach and amusement parks. To me, while hearing these songs, it is pretty easy to imagine people meeting up on the boardwalk during Coney Island's heyday.

3 notes

·

View notes

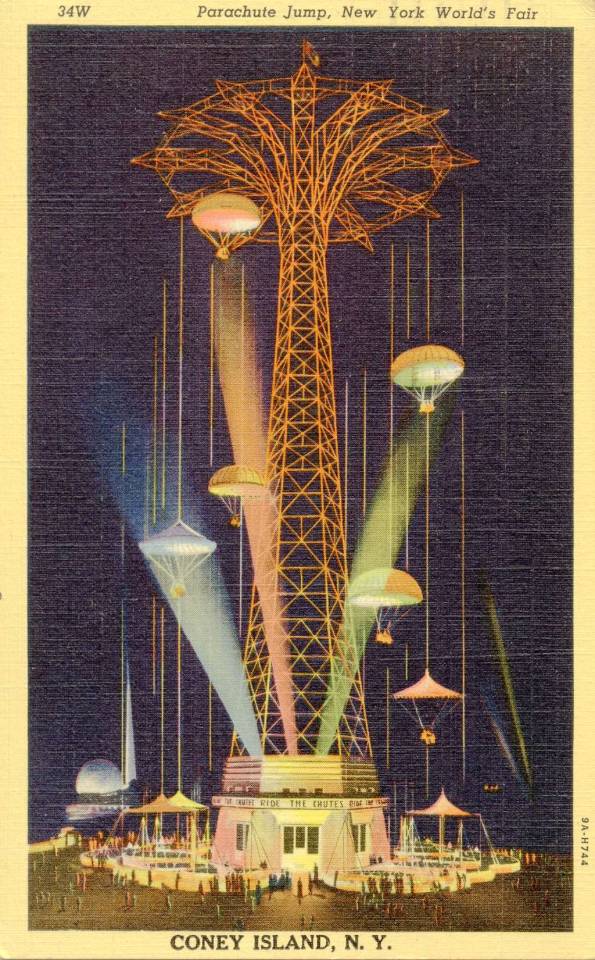

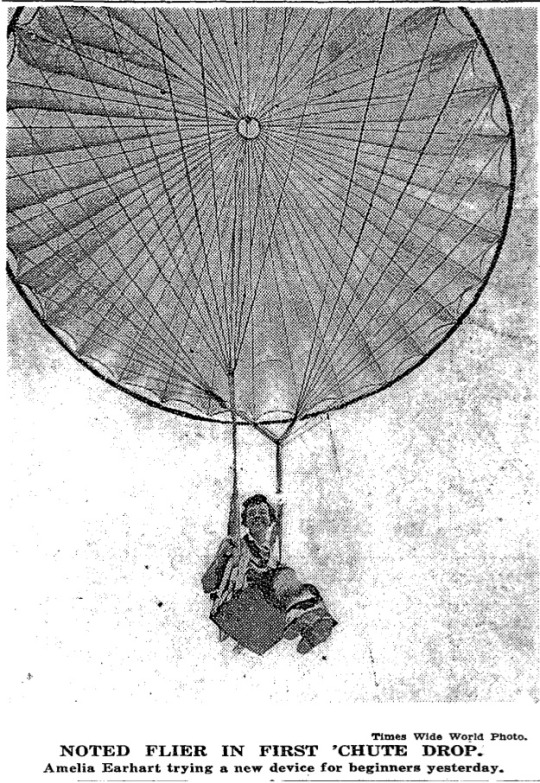

Photo

I had the exciting opportunity last week to visit the Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscripts library to view a collection of Coney Island memorabilia, papers and drawings. While, I ultimately did not find what I was looking for, I had an incredible time sorting through boxes and boxes of notes and papers, often containing little snippets of information I hadn't come across before. While reading one of the letters, I saw a reference to "the parachute jumps in Russia." Taking mental note of it, I decided to dig a little bit into the history of our beloved Parachute Jump, and see if I could find out more about its origins.

The idea of the Parachute Jump was originally conceived by Stanley Switlik and George Palmer Putnam (Amelia Earhart's husband), as a training tool for soldiers. Switlik formed the Switlik Parachute Company, and with Mr. Palmer, built a 115 foot tower on his property in New Jersey, from which Amelia Earhart was the first jumper.

New York Times, June 3, 1935

The original "Russian Parachute Jumps" I saw referenced in the archives, were precursors to Switlik's structures, though they were made of wood, and were rather dangerous, as jumpers were known to collide with the towers. Several of these towers were eventually built on military bases all over, including those in New Jersey and Georgia. They offered new paratroopers safe training on the towers, before making actual parachute jumps from airplanes.

image via

The existing Parachute Jump was built as an amusement attraction for the 1939 World's Fair, and was originally sponsored by Life Savers Candy. It was extremely popular among fair-goers.

image via

New York Times, May 28, 1939

The structure was eventually purchased by George C. Tilyou to become an attraction at Steeplechase Park, where it remained in operation until 1968. It has narrowly escaped demolition a handful of times. Fred Trump wanted to demolish it to make room for condominiums, and it was failed to be bid upon in auction in 1971, and in 1977. It received National Landmark status federally in 1980, and in 1989 by the city. Thankfully, the "Eiffel Tower of Brooklyn" is safe and protected. Now to get it up and running again...

3 notes

·

View notes

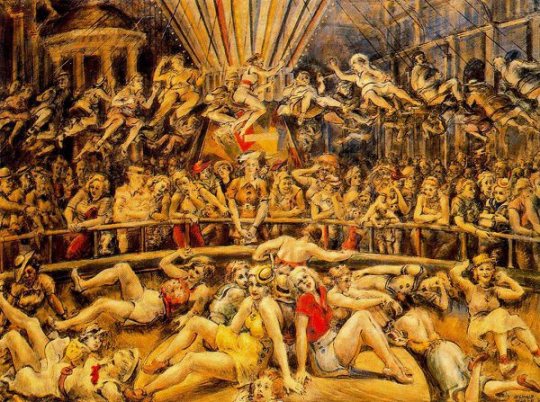

Photo

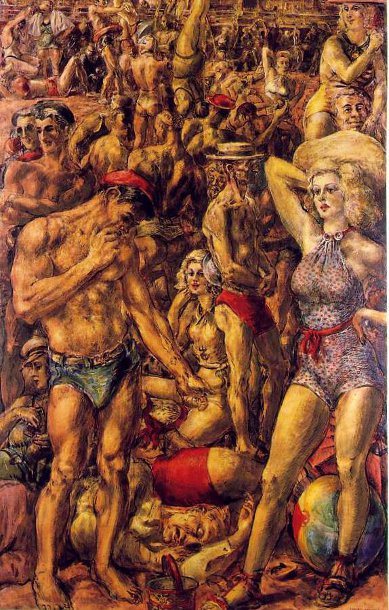

George C. Tilyou's Steeplechase Park, collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (image via)

Everyone who is at all familiar with Coney Island history is aware of its influence in so many facets of American culture - from film, to literature, to art. I would like to occasionally highlight some of the important American artists that used Coney Island as inspiration. The 1910s through the 1950s were an important period in the introduction of Modernism in American art, and are also often considered the larger heyday of Coney Island. With the huge crowds, the diversity of the people, the (at times) vice-filled activities, and the large, beautiful amusement parks, it is no wonder it was such a frequent subject for artists of the time.

image via

The artist that is probably the best known for his depictions of Coney Island beaches, amusements, burlesque shows, and rides is Reginald Marsh (1898-1954). Born in Paris, and raised in New Jersey, Marsh studied at Yale, where he became the illustrator for the Yale newspaper. He later studied at the Art Student's League in New York, where he was taught by George Luks. He used a variety of media, including oil, lithograph, drypoint etching, and egg tempera. He kept many sketchbooks during his summers spent in Coney Island. Marsh rejected the modernists, and referred to himself as a Social Realist.

What, to me is most remarkable was his ability to capture the energy of the people - the crowds, the movement and the interaction. The paintings almost writhe with action!

Coney Island 1936, Syracuse University Art Collection (image via)

image via

While Marsh's painting above, was made several years after the above photograph, the effect of the crowd is the same. It perfectly captured the spirit of the area. I hope to revisit the work of other iconic artists and their depictions of Coney Island in future posts.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Despite how long I have been researching Coney Island history and writing this blog, I am forever surprised at where my research takes me. Rarely do I end up writing the post I intend to write, because in gathering information, I always come across something I never thought of, or knew about. Those surprising little tidbits tend to become the topics of my posts, and I have to learn to begin my research with an open mind.

I intended on investigating the imagery on a postcard in our collection depicting a revolving airship tower, that to me, looked like a fantasy illustration of an existing ride. I did not find any information on the "Rotating Air Ship Tower, but upon further digging, I found out more about Coney Island's connection to early flight.

I did come across the top image via Shorpy of the "Revels of Japan" Japanese Teahouse, with a sign advertising an Airship! What was this?! It turns out that in the gardens of the teahouse, was a parked airship available for visitors to view. It was build in 1903 by Brazilian aviator and inventor, Alberto Santos-Dumont, and was named Airship #9, or "La Baladeuse." It was designed to be an easy way to travel, and Santos-Dumont was known to make personal visits with it.

image via

Aviation was the craze at the time, with the Wright Brothers also making their first flight in 1903. This fascination is reflected in many images in Coney Island souvenirs, with postcards and souvenir photographs of people posed inside fake airplanes and airships.

The romanticism of air travel, at the time, seemed to fit in perfectly with the fantasy of Dreamland.

3 notes

·

View notes

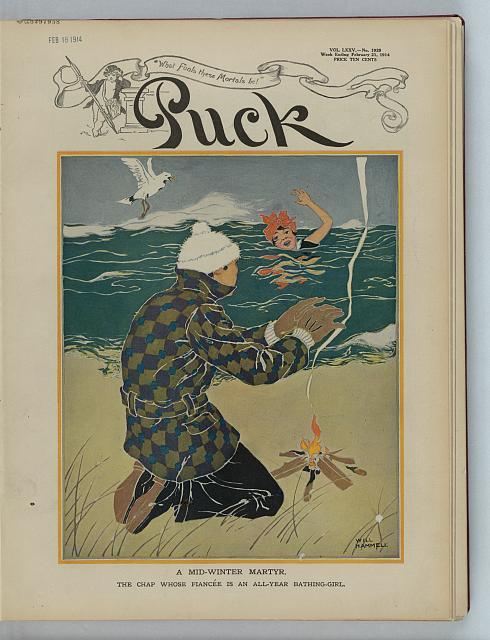

Photo

Puck Magazine, February 21, 1914 (image via)

As everyone knows, yesterday was New Year's Day, and with that comes the annual Coney Island New Year's Day swim. It is organized every year by the Coney Island Polar Bear Club and has always raised money for charity. It also brings luck and a good year to those that jump in every January 1st.

While I knew that every year, hundreds and sometimes thousands come to Coney Island for New Year's Day, what I didn't know is that winter swimming has a very long history in Coney Island, and was extremely fashionable around the turn of the century.

New York Times, January 8, 1908

The Coney Island Polar Bear Club is the longest-running winter swimming club in the United States. It was founded in 1903 by Bernarr Macfadden, the self-titled "Father of Physical Culture," who promoted winter swimming as a health-building activity.

Bernarr Macfadden (photo via)

He began the magazine Physical Culture, in 1899, in which he published many of his ideas about good health and fitness. Among them were the promotion of exercise, the drinking of milk, sleeping on hard surfaces, regular sex, and fasting. He warned against the dangers of eating white bread, wearing corsets, drinking, smoking, taking medication and wearing glasses.

The cold baths were supposed to promote vigor, strength, good circulation and better overall health, though today I think most do it for the fun of it.

So, in the spirit of a freezing-cold New Year's day plunge, I hope everyone has a happy, healthy, vigorous New Year.

For more information about Coney Island USA and our hurricane recovery efforts, please visit www.coneyisland.com.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I fully intended on writing a post a couple of weeks ago about how we have packed up the Niagara Falls Museum collection, and are preparing to go dark for renovations during our off-season. I wanted to include some funny remarks about the things I never foresaw being able to put on my resume. Unfortunately, I got sidetracked and the post was never completed. Now there are much more serious issues at hand.

Coney Island USA has been very hard hit by Hurricane Sandy. The combination of the rising storm waters from the ocean, and the flooding of the Coney Island Creek brought 4-5 feet of toxic, sewage-filled water into the first floor of our building. Everything is destroyed. Miraculously, our museum collection and archives were spared. Thankfully, all of our people and pets are OK, and we expect to reopen in the spring, but it's going to be a very long haul.

As discussed in a previous post, Coney Island is no stranger to disaster. It has been burned to the ground, and rebuilt many times. George C. Tilyou famously charged 10 cents to view the wreckage of Steeplechase Park, after it was burned to the ground in 1907. He posted a sign that stated "To enquiring friends: I have troubles today that I had not yesterday. I had troubles yesterday which I have not today. On this site will be built a bigger, better, Steeplechase Park. Admission to the burning ruins -- Ten cents." It was eventually rebuilt.

Right now, we need your help. We have already begun to clean up. If you wish to help, we are accepting donations of supplies and money, and need volunteers to help with the cleanup. Donations and volunteer inquiries can be made on our website. Please share this widely, as it is essential to our recovery.

-Katie Karkheck

6 notes

·

View notes

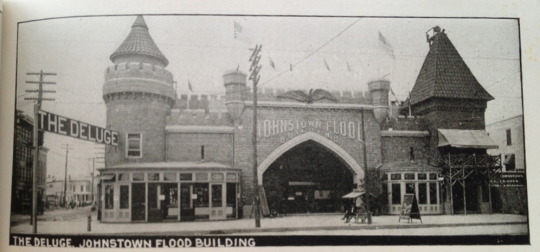

Photo

Ever since I started going to concerts, when I was 13 or 14, I have been a rather vigilant ticket stub collector. While I have never been organized or motivated enough to make a concert ticket scrapbook, or anything like that, I do have many stubs for the many shows I have attended. By going through them, I can instantly recall the goofy antics of one performer, the place where I was in my life, or the dance party that broke out despite the stifling heat in the venue.

I lament the shift from physical, heavy paper tickets, to online printouts, because the printouts make terrible keepsakes. As a museum worker, I get to handle the normally thrown out scraps of the past. The scraps and ticket stubs from early Coney Island are infinitely more interesting than my stack of ticket stubs. The truly beautiful dove, shown above, was the ticket stub for a theatrical attraction called the Deluge.

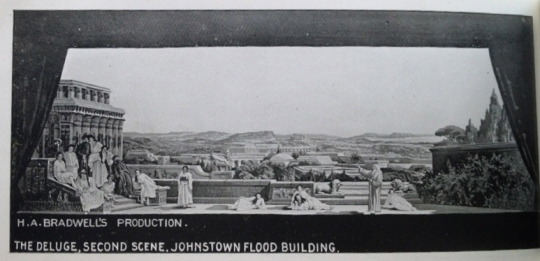

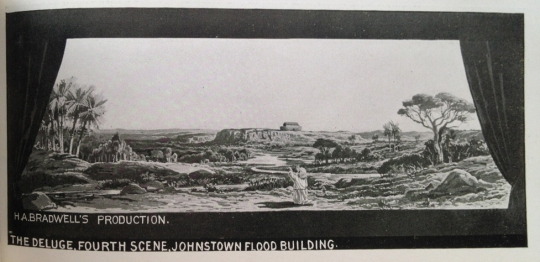

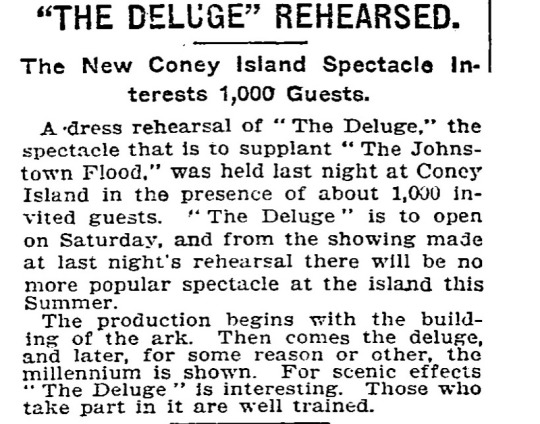

from Coney Island: The People's Playground a Souvenir Book, 1906

The Deluge was created by Amusement Entrepreneur, H.A. Bradwell, and opened in May 1906. Bradwell was responsible for having created other popular attractions in Coney Island, like the Vengeance of Vesuvius, The Jonestown Flood, Feltman's Ziz, and Dreamland's Creation. It seemed that he specialized in large-scale theatrical recreations of disasters or monumental events, though he advertised that he could build anything in the amusement industry.

The Billboard, March 9, 1907

Located in the former Johnstown Flood building, The Deluge was one of a handful of biblical-themed attractions in Coney Island at the time. It recreated the story of Noah and the Ark, beginning with actors carousing in a temple at finishing with the ark on top of Mount Ararat.

from Coney Island: The People's Playground a Souvenir Book, 1906

from Coney Island: The People's Playground a Souvenir Book, 1906

It was quite a popular spectacle. I like to think of Dreamland's version of the large-scale, blockbuster, CGI disaster movies of their time, full of drama and doom. The tickets are certainly more interesting!

-Katie Karkheck

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the objects that first caught my eye when I first started working here was this set of old stilts. They are beautiful objects, made out of wood and leather. They even have their own shoes!

The wearer would strap his or her feet onto the platforms at the top of the stilts and start walking.

The wearer would look something like this:

photo courtesy of deleonhistory.com

I wondered where these stilts had come from and whether they were used in vaudeville performances, parades and other forms of entertainment. Surprisingly, they were not. These stilts most likely used by a local candy store for advertisement purposes!

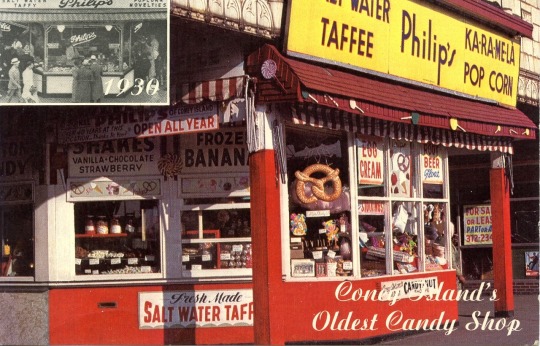

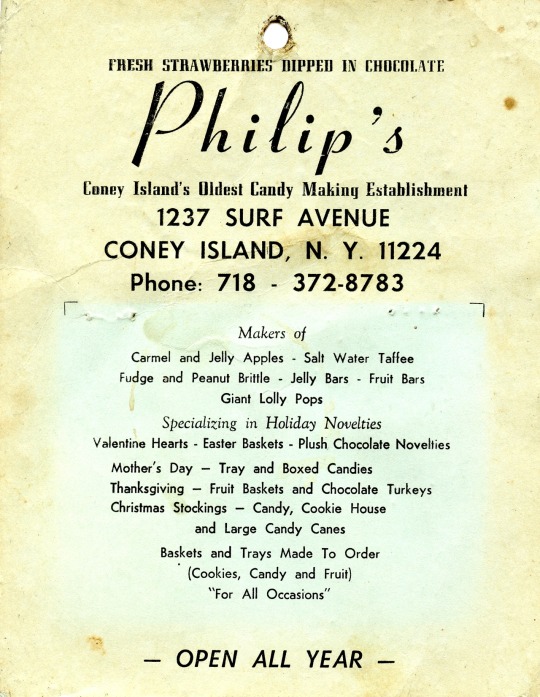

Philip's Candy Store postcard

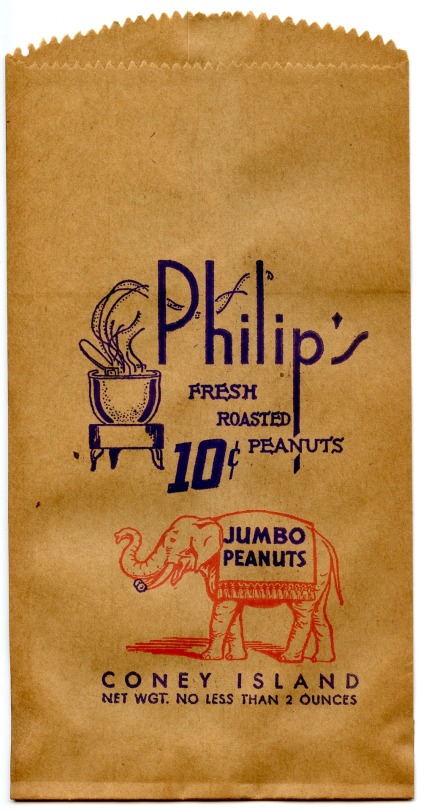

Philip's Candy Story was a fixture on Surf Avenue from 1931 until 2001. In its early days, the owners of Philip's would hire young boys to wear sandwich signs and stilts to walk on the boardwalk, encouraging people to come in, and functioning as walking billboards. Philip's was highly regarded for their homemade candies, fudges and confections of all kinds.

Early Philip's Candy Shop advertisement

Peanut bag, Philip's Candy Shop

Sadly, Philip's Candy Shop closed in 2001, when the Stillwell Ave. train station was being renovated. Philip's was the only remaining tenant in the station, and the shop had to be demolished. Many devoted fans of the shop were sorry to see it close. John Dorman, Philip's owner and candy maker for 54 years, reopened the shop in Staten Island as Philip's Candy of Coney Island.

For those looking for a remnant of Philip's Candy Shop in Coney Island, one has to go no further than our own gift shop. The entire front sign advertising its "Ka-Ra-Me-La popcorn" and "Salt Water Taffee" is above the entrance to the museum in the gift shop. Next time you are here, look up on your way into the museum, and think of the young boys on stilts advertising a Coney Island institution.

- Katie Karkheck

5 notes

·

View notes