Text

9. References

Aboriginal homelessness count in Metro Vancouver. (2018). Aboriginal homelessness – 2018 homeless count [PDF File]. Retrieved from http://infocusconsulting.ca/wp-content/uploads/ABORIGINAL-HOMELESSNESS-Aug-2018-Final.pdf

Care Quality Commission. (2018). Service types. Care Quality Commission. Retrieved from https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/regulations-enforcement/service-types

Caryl, P. (2018). No home in a homeland: Indigenous peoples and homelessness in the Canadian North, Canadian Journal of Sociology (Online),43(1), 85-88. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/nahs/docview/2030653905/fulltext/A65B44D098C34058PQ/5?accountid=13631

Correctional Service Canada. (2019). Correctional service Canada healing lodges. Correctional Service Canada. Retrieved from https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/aboriginal/002003-2000-en.shtml

Dennis, C. (2018). A new study on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls highlights challenges. Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved from https://nonprofitquarterly.org/a-new-study-on-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-and-girls-highlights-challenges/

Edwards, K. (n.d.). Fighting foster care. Maclean’s. Retrieved fromhttps://www.macleans.ca/first-nations-fighting-foster-care/

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Indigenous harm reduction principles and practices fact sheet [PDF File]. Retrieved from http://www.fnha.ca/wellnessContent/Wellness/FNHA-Indigenous-Harm-Reduction-Principles-and-Practices-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Gaetz, S., Dej, E., Richter, T., & Redman, M. (2016). The state of homelessness in Canada 2016 [PDF File]. Retrieved from https://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC16_final_20Oct2016.pdf

Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, A., Harris, B., Hill, C., Kovacs-Bums, K., … Marsolais, A. (2012). Canadian definition of homelessness [PDF File]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHhomelessdefinition.pdf

Giphy. (n.d.). Shocked Oprah Winfrey GIF. Giphy. Retrieved from https://giphy.com/gifs/shocked-oprah-winfrey-Ld7IFYuds4MA8

Hadjipavlou, G., Varcoe, C., Tu, D., Dehoney, J., Price, R., & Brown, J. A. (2018). “All my relations”: Experiences and perceptions of Indigenous patients connecting with Indigenous Elders in an inner city primary care partnership for mental health and well-being, Canadian Medical Association,190(20), 608-615. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171390

J Hollinshead. (2017, June 18). Resilience from an Indigenous perspective [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://peak-resilience.com/blog/2017/6/18/resilience-from-an-indigenous-perspective

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. (2014). Missing and murdered Indigenous women in British Columbia, Canada [PDF File]. Retrieved from http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/indigenous-women-bc-canada-en.pdf

Menzies, P. (2009). Homeless Aboriginal men: Effects of intergenerational trauma [PDF File]. Retrieved from https://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/6.2%20Menzies%20-%20Homeless%20Aboriginal%20Men.pdf

Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2018). Indigenous women, intimate partner violence & housing [PDF File]. Retrieved from http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/issuebased_newsletters/Issue-25/Issue_25.pdf

Pelley, L. (2017). Precarious housing means thousands may live on brink of homelessness. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/precarious-housing-1.4036116

Postcolonialism. (n.d.). In Wikipidea. Retrieved June 13, 2019, fromhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postcolonialism

Schmunk, R. (2019). Home prices in Vancouver are quadruple what average millennial can afford: report. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/home-prices-vancouver-twice-what-millennials-can-afford-1.5172388?fbclid=IwAR0eDN-Ggp4EoHxSGMXh1FFkL8_DqCwlY5xI9ZL6YM5PaS0k6uRXS-u0mWM

Smee, M. (2019). Locals object to Indigenous healing lodge in Scarborough neighbourhood. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/locals-object-to-indigenous-healing-lodge-in-scarborough-neighbourhood-1.5171332?fbclid=IwAR1uFATyjFHvho_CC_WGNhsbaNFbFA2m8oTvc815pNuXXjy58lk82C7HMT8

Stamler, L. L., Yui, L., & Dosani, A. (2016). Community health nursing: A Canadian perspective (4thed.). Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Stardustedit. (2017, December 15). Aesthetic headers [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://stardustedit.tumblr.com/post/168575481098

The Lancet. (2016). Canada’s inquiry into violence toward Indigenous women, The Lancet, 732. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)3143-1

Thistle, J. (2017). Definition of Indigenous homelessness in Canada [PDF File]. Retrieved from https://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHIndigenousHomelessness-summary.pdf

Up With Women. (2019). What causes the risk of homelessness? Up With Women. Retrieved from https://upwithwomen.org/what-causes-risk-of-homelessness/

Urbanoski, A. K. (2017). Need for equity in treatment of substance use among Indigenous people in Canada, Canadian Medical Association, 189(44). doi:10.1503/cmaj.171002

Winter, J. (2018). It’s safer out here. The Globe and Mail.Retrieved fromhttps://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/torontos-homeless-brave-the-cold-rather-than-stay-in-dangerousshelters/article37601534/

Zig Zag. (September 1). Federal study shines new light on homeless Indigenous people, veterans. Retrieved from https://warriorpublications.wordpress.com/2016/09/01/federal-study-shines-new-light-on-homeless-indigenous-people-veterans/

0 notes

Text

8. Next steps - Allyship and social justice

Is your mind blown yet like this Oprah gif? (Giphy, n.d.).

I have thrown so much information at you in a series of eight posts about Indigenous homelessness, with extended information on some of the social determinants of health, colonialism, statistics, and real life stories.

As I learned this in my Homelessness in Canadian Society class, I too felt overwhelmed at the information, some of which I already knew, but there was so much information that I did not know of, or was not aware of, at all.

But that is okay! It means that you are still learning.

Now in terms of tackling Indigenous homelessness as a whole, it can be overwhelming if we start thinking about solutions on how we can alleviate this issue. In nursing school, I learned about the impact of community development work and the Population Health Promotion model (Stamler, Yiu, and Dosani, 2016).

The Population Health Promotion model combines the social determinants of health, strategies for health promotion, and levels of action in one big frame. While this model mainly sheds light on health promotion, we can also apply its concepts to tackling the issue of Indigenous homelessness (Stamler et al., 2016). Homelessness and social justice activists often work at the community level where we may see these folks protesting on social justice issues in front of Toronto’s Old City Hall or Queen’s Park. At the individual level, we may start small by learning as much as we can on the causes and implications of Indigenous homelessness. This can be done through self-reflection if we start asking ourselves: What are my pre-assumptions of those experiencing homelessness? How can I better educate myself on this issue? What are the social determinants of health and how are they connected to Indigenous homelessness? These are good questions to branch off of. Once we gain this knowledge, we may educate others on this topic by creating a supportive and learning environment.

Furthermore, you may be thinking about strategies that go beyond the individual or community level. For example, at the system/society level, you may be involved in building healthy public policies that include Indigenous people or you may act on the strategy of re-orienting health services by advocating for an overdose prevention site to be made in your town area, for example. The options are limitless.

Most importantly, we must remember to be an ally with the people. To be an ally means to question the status quo, standing in solidarity with the Indigenous folks, and advocating with them. We must learn and listen in an ongoing partnership with the Indigenous people as we move forward as we continue to advocate with those experiencing Indigenous homelessness.

Finally, as I near the end of my last post, I remind you to take a moment to reflect on what you have learned. Did you learn something new? Did something stand out to you? How did you feel? I encourage every reader to spread awareness on Indigenous homelessness. Share your thoughts with a friend, family, coworker, or send me a message! I accept anonymous questions. Let’s keep the conversation going. Thank you for reading.

P.S!!!! IF you are looking for ways to get involved, check out this link! https://www.211toronto.ca/topic/homelessness This website also lists a ton of resources/services for those who need them!

0 notes

Text

7. Resiliency

Now you must be thinking to yourself: “I.. have no words. I don’t know how Indigenous people stuck it out for so long…”Believe me, I thought about this too.. and admittedly, I still do! I am non-Aboriginal. Sometimes when I read the news or listen to stories from Aboriginal people, I feel a tinge of sadness, anger, and helpless. I feel terrible hearing about the tragedy of residential schools, the erasure of their Aboriginal identities, and the growing number of Aboriginal children separated from their families. I feel angry at the system and sad because of how we failed to support or include Indigenous people in our Canadian policies. But what I have learned after hearing from other people’s stories and after reading through pages of research online and from brochures, is that Indigenous people are resilient. While they are deemed as a ‘vulnerable population’, they are strong and very, very resilient people. The common narrative that we see and hear are that Indigenous people feel helpless and are the victims of society. This is partly true when we look at the ongoing problem of racism and colonialism in Canada.

But what we do not often see are the level of resiliency that Indigenous people have. According to Hollinshead (2017), Indigenous people who overcame trauma, the loss of their identities, language, and culture learn how to build resiliency over time through relationship-building, activism, and community development work. The concept of building resiliency has always fascinated me for a long time. I think it’s important to remember that although Indigenous people have lived through multiple traumatic experiences, they are still strong and they will continue to advocate for themselves and with others.

0 notes

Text

6. Harm Reduction

From my previous post, I wrote about the need for cultural-appropriate services and how they may benefit Indigenous people experiencing homelessness. For this post, I will write about the philosophy of harm reduction and how harm reduction services is viewed in Indigenous culture. Lastly, I will explore the connection between harm reduction and Indigenous homelessness.

While in school, I had the honour of participating in a Durham women’s health conference as a public speaker. For the first time, I delivered a speech in front of nursing students, community members, and service providers. It was a very rewarding day as I had the pleasure of listening to many people’s stories. One speaker was Indigenous and her topic was on harm reduction and how it is connected with Indigenous values and perspectives. I was fascinated by her talk to the point where I urged myself to learn more about harm reduction from an Indigenous perspective.

I will start by defining what harm reduction means and what it entails. Harm reduction, in the literal sense, means to reduce harm. For example, a seatbelt policy in cars is a harm reduction policy as it enables passengers to drive safely so that in case of a car accident, their bodies would be safely secured under the belt (P. Murphy, personal communication, June 6, 2019). The standard procedure of putting on gloves before performing a sterile procedure in a hospital environment is another example of a harm reduction policy as we not only protect ourselves from infection but also protect the patients in the hospital. Harm reduction in health care and in community agencies follow a non-judgmental and equitable approach to ‘meeting people where they are at’, especially in the midst of an opioid crisis. Safe injection sites/overdose prevention sites supports individuals who use drugs by educating them safer ways to take their drugs and by providing them safe, sterile drug-related equipment. They are also trained on overdose prevention procedures, which is an important life-saving skill to learn especially if they are intravenous drug users.

Harm reduction from an Indigenous perspective bears some similarities to the Western definition however there are some unique differences.

First Nations Health Authority (n.d.) outlines the symbolic meaning of four animals in connection to harm reduction principles. On the very left side of the symbol is a wolf, representing “relationships” and “care” (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.). The meaning behind the wolf looks at relationship-building, especially with those who use drugs. The top image is the eagle, representing “knowledge” and “wisdom”. The eagle is associated with the idea that the road to recovery from a drug addiction is an on-going and patient process. On the bottom, we have the bear, symbolizing “strength” and “protection”. The bear emphasizes the importance of capacity-building work in harm reduction services and it also acknowledges the meaning of providing cultural-specific care to people who need these services. Lastly, the raven on the right symbolizes “identity and “transformation”. The raven looks at identity exploration and acknowledges that, similar to the eagle, the road to recovery is a journey where we continue to learn more about ourselves and from others along the way (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.).

Harm reduction from an Indigenous perspective is similar to the Western definition of the term as both definitions look at supporting people in a non-judgmental, equitable, and holistic manner. The Indigenous perspective also acknowledges the various context of why one might be using drugs or other substances. Intergenerational trauma, exposure to violence, homelessness, precarious housing, racism, or feelings of a lost identity, could influence someone to use and abuse drugs (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.). The social and emotional impacts of Indigenous homelessness, on top of the accumulated stress, can be overwhelming for many Indigenous people. I also learned that harm reduction entails more than just community outreach services but a key part harm reduction focuses on relationship-building grounded in compassion, empathy, and supportive healing.

To address the issue of homelessness, we must remember to follow a harm reduction approach by ‘meeting people where they are at’, rather than shutting people down. This is important to consider in the context of Indigenous homelessness. It would be more appropriate to support those experiencing homelessness in an equitable and non-judgmental manner. It would be more appropriate to support those experiencing homelessness in an equitable and non-judgmental manner so that rather than letting our fear and judgments take over, we learn to be more open and accepting to one another.

0 notes

Text

5. Access to Indigenous culturally Appropriate Health/Social Services … or lack of..?

Welcome back! I previously mentioned that I will be exploring whether Canada currently has culturally appropriate health and social services for Indigenous groups. A LACK of these services must be addressed if we were to consider addressing the issue of homelessness. While the primary solution to homelessness is affordable housing, we must also question … are there enough culturally appropriate services and programs for Indigenous groups? There are many reasons why one may seek access to these services. But first, let us start by listing what kind of services/programs are there! Care Quality Commission (2018) cites some of which that include child care, health care (sexual health, mental health, physical health), community services, housing services, etc. I found this article written by Urbanoski (2017) and in her commentary, she emphasizes the need for equity in treating Indigenous people who are experiencing some form of substance abuse. While I think it would be more efficient to work upstream (looking at how we can prevent issues from occurring) it is also be important to think about effective downstream methods (treatment) and how we can support Indigenous people in a holistic and equitable manner. Urbanoski (2017) states that on top of providing treatment, service providers must be properly trained on how they can provide appropriate trauma-informed care. As a nursing student, I have met many patients who carried different life stories and lived experiences with them. To fully support them in their care, I wanted to understand their life context. This is especially important for many service providers working with marginalized groups, especially those who identify as Indigenous. Hadjipavlou et al. (2018) emphasizes this for mental health services. In order to support the mental health of Indigenous people, we must not identify their mental illnesses as separate incidents. Instead, we must understand the context of their mental health and also understand how racism, colonialism, and inequity affect their mental well-being. (Hadjipavlou et al., 2018).

In addition to providing culturally appropriate health services, we must also look at other types of services that may benefit Indigenous people. While scrolling on Facebook, I came across an article that piqued my interest. Author Smee (2019) wrote about Toronto’s two-year plan of building an Indigenous healing lodge in West-end Scarborough. To provide some context, healing lodges are not like the traditional jail centres that we see in film and television. Indigenous healing lodges provide services and programs to Aboriginal inmates specific to their culture, traditions, and values (Correctional Service Canada, 2019). Some locals in the neighbourhood actively opposed this idea by stating that the implementation of this lodge may compromise their children’s safety (Smee, 2019). For these locals, they associate Indigenous members with criminal activity. It is unfortunate to see that fear can affect how we perceive other people. But this healing lodge may be the best alternative to Indigenous people than institutionalizing them in traditional jail centres. These lodges not only follow Aboriginal values but they also assist inmates with basic life skills, therapy, relationship-building programs, support, and healing services (Correctional Service Canada, 2019). Incarcerated individuals experiencing Indigenous homelessness may benefit from holistic services and programs that are specific to their culture and way of life.

We must remember that as Canada’s population grows larger, our demographics continue to change as well. Therefore, service providers in the health care and social services field must be properly equipped in providing appropriate cultural specific care to a diverse group of people. Inclusivity is important to think about if we are working with marginalized communities.

0 notes

Text

4. Violence and Indigenous women

I must address a possible trigger warning before we delve further into this topic on violence and abuse. As a reader, if you feel uncomfortable or experience flashbacks while reading this post, please take the time to take care of yourself. Your health comes first.

To start, there is indeed a relationship between violence and homelessness. Violence can take on many forms. There is physical violence (ex. hitting, punching, kicking, restraining), emotional violence (ex. verbal abuse, insult), sexual violence (ex. non-consensual sex, coercive sex), and spiritual violence (ex. forcing someone to follow a certain religion). According to the Ontario Native Women’s Association (2018), Aboriginal women are more likely to experience violence than non-Aboriginal women. Aboriginal women may choose to leave their homes if they have experienced some form of abuse inside of their homes. As a result, they may experience homelessness if they lack the social supports and have no where else to stay. While circumstances such as these can also be seen in all women, there is still a higher representation of Aboriginal women who experience violence and homelessness (The Lancet, 2016).

If you reside in Canada, you may be familiar of the report that detailed the number of Indigenous women who have been missing, performed suicide, or have been murdered. In 2012, there were 120 documented cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women reported in British Columbia (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2014). It is unsettling to think that while 120 may sound like a low number, it is probable that there could be a higher number of cases that went unnoticed (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2014). It is important to remind ourselves of the discrimination and racism that existed and still exist against Aboriginals peoples to this day. In addition to the fact that there has been a high representation of Aboriginal kids placed in foster care and in unstable homes, we must also acknowledge the vulnerability of Indigenous women today. Indigenous women not only experience homelessness, but they may also experience various implications of homelessness such as poverty, low education, food insecurity, and most importantly, exposure to violence (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2014). As we know, there are a number of social determinants of health that can impact the way we live daily. These determinants include food insecurity, education, early childhood development, income level, race, etc. For Indigenous women, it becomes much harder for them to advocate for themselves if discrimination and systemic racism still exist.

Furthermore, those who need adequate income may resort to engaging in high-risk activities such as sex work or drug use (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2014). This is not to generalize the experiences of all Indigenous women. But from what I have learned in school and in my interactions with those who have experienced homelessness, the reality is that individuals do what they can in order to survive. They may engage in high-risk behaviours in exchange for money, for example. As I have previously mentioned from my first blog post, it is also important to reiterate that exposure to violence is a precursor to Indigenous homelessness. Long-term exposure to violence may lead to trauma, that can be passed to generations (intergenerational trauma), that may affect one’s social, mental, and physical well-being.

So far, in all of my posts I discussed the defining question of how Indigenous people navigate and/or experience homelessness. You may see a pattern that one topic cannot be isolated from another. Every issue intersects. This is important to think about when addressing the overall issue of Indigenous homelessness.

For my next post, I will write about how Indigenous folks navigate healthcare/social services. I will also explore why it is important to implement culturally appropriate services/programs in order to address those experiencing Indigenous homelessness.

0 notes

Text

3. How is Intergenerational Trauma linked with Indigenous Homelessness?

According to a study done by Menzies (2009), homelessness has been linked with trauma experienced by most Aboriginal peoples. When Canadians colonized the Aboriginals, they sent Aboriginal kids into residential schools where they are then assimilated into White Canadian culture, language, and religion (Menzies, 2009). Those who are caught speaking their own language or display any sign of their Indigenous culture would be subject to punishment, and often times, assault. As a result, Aboriginal children were forced to endure years of abuse, trauma, and pain at the hands of non-Aboriginal people. Children were separated from their families, language, traditions, and most importantly their identities (Menzies, 2009). According to Menzies (2009), this long-time trauma impacted their health in many levels: physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually.

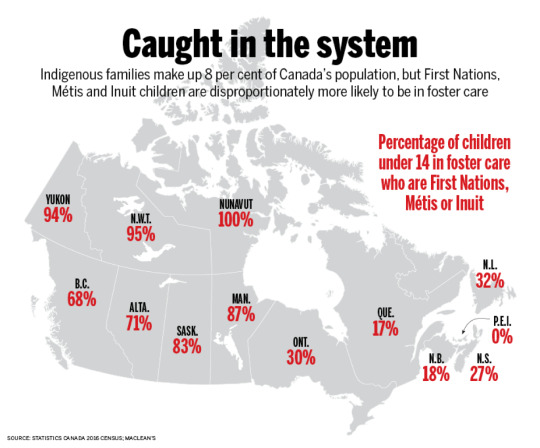

To visualize this, I found an article that included an infographic detailing the percentages of Aboriginal children under the age of 14 placed in foster care in Canada (Edwards, n.d.). The results are staggering. The statistics came from the year 2016.

While the map shows that 0% of Aboriginal children are placed in Prince Edward Island, there is a stark contrast between P.E.I. and in other provinces. There are higher percentages of Aboriginal children placed in foster care in Western provinces than in Eastern provinces (Edwards, n.d.). Still, it is shocking to see that many of these children would be described as homeless as they are separated from their families. The effects of colonialism has caused these children to be moved into foster care or non-Aboriginal homes; in homes that they are unfamiliar with, with faces that they do not recognize, and in a culture that is not theirs. On top of experiencing homelessness and the burdens of their long-term trauma, Aboriginal children are at higher risk of experiencing mental illnesses, drug or substance abuse, low self-confidence, or violence and abuse, (Menzies, 2009).

For my next post, I will explore further the ways in which Indigenous women experience violence inside and outside of the home, and how violence in Indigenous groups contributes to homelessness.

0 notes

Text

2. Who is at risk of experiencing homelessness?

Now that you have gained some basic understanding about homelessness and the preceding factors of this long-standing issue, let us delve into: Who is At Risk of Experiencing Homelessness? For the purpose of my final assignment, I will be specifically focusing on Indigenous Homelessnessand the larger, social implications of this issue. Now, while I will be writing about issues and topics that pertain to Indigenous groups and Indigenous cultures, I must claim that the purpose of this blog is to NOT write on behalf of Indigenous folks as I identify as non-Aboriginal.

Let us start with this infographic: According to a report from the Aboriginal Homelessness 2018 Count in Metro Vancouver (2018), there is a large representation of Aboriginal people experiencing homelessness in one year than their Non-Aboriginal counterparts. In addition to this, if they are Aboriginal, they are at higher risk of experiencing one or more adverse health conditions (Aboriginal Homelessness 2018 Count in Metro Vancouver, 2018). From this statistic, it would not be surprising to conclude that those who experience homelessness may be more likely to die at an earlier age compared to those who live in safe and permanent homes.

Furthermore, since I am focusing on homelessness from an Indigenous perspective, it would be suitable to define the term homelessness that is appropriate to their culture. From my previous post, I made it clear what the term homelessness would mean to Western folks: the inability to afford or secure safe and permanent housing. However, from an Indigenous perspective, the state of being homeless would describe one’s isolation from their land, kin water, their language, and their identities (Thistle, 2019). This definition goes beyond the absence of a physical home. For Indigenous people, homelessness can mean the inability to connect with their people and their land emotionally, culturally, and spiritually (Thistle, 2019). Indigenous homelessness is a recurring issue and has been an issue for many years now due to colonialism.

Canada has long been praised as a multicultural country, and for many Canadians we embrace this part of ourselves very proudly. We like to separate ourselves from the Americans. We take pride in our country’s diversity. We take pride in our food, our culture, our music. But what we fail to acknowledge is the lack of respect that we have for Indigenous peoples. This is not something to be proud of, and yet, because we turn a blind eye to Indigenous folks, we are ignoring the impacts of colonialism. We are ignoring Indigenous voices. You may ask: But what is colonialism and how is it related to indigenous homelessness?

To put it simply, colonialism describes the way in which people from one country visit another separate country to take over their land and resources. Do you remember when the British colony took over Africa and made Black folks into slaves? Or when the Spanish colonized Philippines into making it theirs? Those are examples of Colonialism. POST-Colonialism bears a similar definition to colonialism but post-colonialism looks at the effects of colonialism on impacted groups and countries (Wikipidea, 2017).

Many Indigenous individuals have long been affected by colonialism for many years now. Colonialism has impacted Indigenous homelessness in a number of ways. Because of colonialism, Indigenous groups have been excluded from Canadian social policies (Caryl, 2018). I will explain this further in my next post on the impacts of colonialism and how this has impacted Indigenous homelessness very soon! Stay tuned.

0 notes

Text

1. Let’s talk about this: those who are experiencing homelessness are NOT lazy people.

You guessed it. The people that we see on the streets in downtown Toronto, sitting on the floor in bus shelters, lingering outside safe injection sites, or those waiting in line in emergency shelters, are people that we see almost everyday. As a student at Ryerson University, I always dread my commute to school. It pains me to wake up early everyday and experience delays in the TTC subway system. I would call myself lazy. But I would never call people who experience homelessness lazy. This is because I do not know them. I do not know how or why they ended up on the street. I refrain myself from judging others.

So if they are not lazy, why don’t they work harder? Why can’t they just get off the streets? Why can’t they find a job?

As unbelievable as this may sound, these are good questions; these are questions that we need to examine further. Before delving into these questions however, it is important that we must first understand some key terms.

Homelessness, according to Gaetz et al. (2012), is defined as the state of which an individual lacks, or is unable to have, safe and permanent housing. Up With Women (2019) mentions some reasons as to why one may experience homelessness:

· Being laid off

· Abuse and violence

· Lack of affordable housing…

· (due to..) Gentrification – which is the process of restructuring a neighbourhood to better suit the needs of the middle class and/or upper class citizens

· Natural disasters

· Poverty

One may also experience ‘precarious housing’ if one is already at risk of experiencing homelessness (Pelley, 2017). For example, a new immigrant woman renting a place in Toronto may experience precarious housing if she lives her days paycheque by paycheque but is employed with a low-paying job. She may not have the proper means of paying her rent which places her at risk of experiencing homelessness. To “get a job” is easier said than done. Speaking from experience and from the conversations that I share with my friends, a college degree is not easy to obtain. One would have to work harder to be able to afford school. In addition to this, one may settle for a low-paying job with little to no benefits, has little hours, that requires heavy, physical labour. Low-paying jobs with heavy physical labour may affect workers’ physical health as well. Furthermore, if we were to tell someone to “get off the streets” where should they go? It has become more expensive now to afford a house. According to Shmunk (2019), housing in Vancouver has become much harder to afford for millennials, as a single house requires double the average income! And if not single homes, shelters has been perceived to be dangerous for some, and life-threatening for others (Winter, 2018). So where else canthey go?

In short, homelessness cannot be fixed with a ‘one size fits all’ mentality. You may want to consider WHY it would be not that easy to “just get a job” or the reasons why folks cannot “get off the streets”. Ultimately, we must learn not to judge others and instead be informed and actively learn about the greater, societal issues that exist around us, especially when it comes to homelessness.

1 note

·

View note