Text

Girl 1 music versus Girl 2 Music

“See You Again (feat. Kali Uchis)” by Tyler the Creator is a great song. Watching people sort gender presentation by the lyrics is less than great.

If those first two sentences seemed absurd, it’s because they are, all things considered, to the average person. The context will not make it much better, but instead dismantle this concept and piece together what happened to make such a thing reality. It’ll be a long walk; stay with me.

We’ll start at the beginning. For hundreds and hundreds and even thousands of years, there has been a concept of “those” people, a disparaged “other”. The evolution of a stratified society and predefined societal roles exacerbated the issue of classifying people as well as it did the issue of classifying those who fail to fulfill a role, or who fulfill a role we particularly dislike.

Unfortunately, a lot of the burden for classified ‘others’(so to speak) has fallen onto women. Certain definitions of proper, traditional femininity are utterly stifling in their restrictions and equally punishing for deviation from said restrictions. There are ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ ways to be feminine. Though this is less restrictive (perhaps just restrictive in a different way)—nowadays, the roots of policing and judging women for how they exist while being women persists. As far back as 1851, editorials warned of women with “an obvious tendency to encroach upon masculine manners, manifested even in trifles, which cannot be too severely rebuked or too speedily repressed”. They were certainly rebuked. Victorian women couldn’t even ride bicycles for a while without being mocked for ‘bicycle face’, or being told that their organs would get jumbled to death if their fragile uterus dare brave the ride of a velocipede. The emerging trend of wearing bloomers (billowy big pants) met harsh criticism as well—how dare women engage in such mannish behavior…like…. pants. This policing of women’s’ existence has always had its ugly trivial side. On the more extreme side of things, suffragettes fighting for women’s’ right to vote were cast as angry, cruel women that would die alone and unloved for their inability to surrender their lives to men. For a modern equivalent, turn to the more recent ‘snowflake’ trope. It gets its name from the phrase ‘special snowflake’, a phrase borrowed from children’s books that used snow as an analogy for all people being unique, and therefore special, in their own way. The ‘special snowflake’ as a stereotype gained popularity in 2016 and 2017. Women and LGBTQ+ folks who people decided were a little too unique were slapped with this label. Easy bullying. Anything from using they/them pronouns to being visibly queer or even just protesting a misogynist joke would get you thrown in this bin. I myself was, confusingly, labeled a snowflake when I did a class presentation by myself since my groupmates had done nothing. Honestly it made no sense. The snowflake thing by itself didn’t either, though—it was just slapping a target onto the back of people that society could easily deem nonconforming. Such people using the ‘snowflake’ term thought the nonconformist existence of minoritized folks was only acceptable as a punchline. Why else would it be okay to be so strangely un-average? Women had possessed the right to vote for almost 100 years by 2016, but heaven forbid a woman wanted to exist in a way that was noticeable.

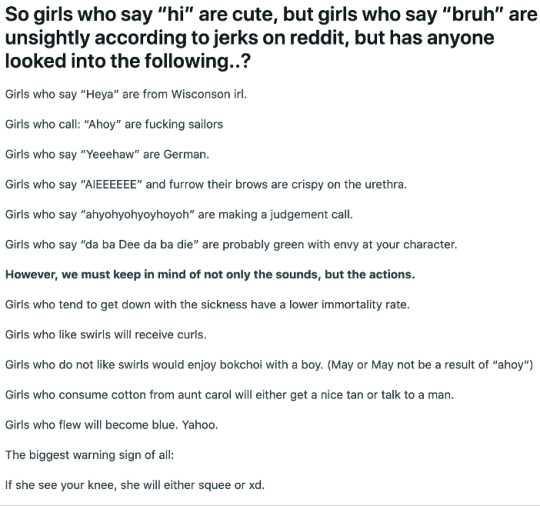

Luckily that trend is long gone. What took it’s place is markedly less of a bully tactic, but still a strange, ambiguous way of categorizing people, and yet another stereotype. Forget the preppy girl, the jock, or the nerd, and make way for the trainwreck that is ‘girls who say hi v.s. girls who say bruh’. I could not make this up. It’s essentially a trend from a couple years ago that made jokes about stereotyping feminine girls (often with the connotation of them being innocent and/or weak) and ‘cool’ girls who are apparently less feminine or something…. essentially a more convoluted ‘type a’ and ‘type b’ for women. As if there wasn’t already enough of that. This is where the music mention from the beginning comes back—the ‘hii’ versus ‘bruh’ girl meme would compare any characteristics from appearance, speech, favorite food, and taste in artistic media between these stereotypes, essentially filing any sort of thing someone could be or enjoy into a category. Hopefully you, reader, can see where this can get messy. Take some real examples:

Already weird and abstract. Back to where we started: “See You Again”. Again, a great song. What happened after the bruh/hi girl thing was that people started to repeat that by categorizing people based on which line of the song’s ending people would sing. “See You Again” ends with Tyler singing “okay okay okay okay” and Kali Uchis harmonizing with some ‘la’s. Literal sounds reappropriated into a ‘type’ of girl. Every action of a woman categorized. In googling examples the first suggestions for ‘okokok lalala girl’ were ‘quiz’ or ‘test’ or ‘difference’—as if one should want to know, to categorize themselves, to fit into being one type of girl or the other and match the media they enjoy and consume to that.

Different iterations of stereotypes persist, of course, it never really ends. Now I often see labels or memes of people’s taste in art as being some sort of nameable, Pinterest-searchable aesthetic—Lana Del Rey is ‘coquette’, Radiohead is ‘femcel’, and with these words go not only music but fashion, speech, body language…sound familiar?

Though definitely strange to process, it isn’t entirely unheard of that this happens. We humans are communal creatures, and undoubtedly finding identifiable communities of shared interest are helpful, but there are caveats to what sort of categorization is helpful and what is a symptom of needing that categorization. I bear no ill will to coquette or femcel or hii or any sort of girl. What I do bear a bit of distaste for is that we live in a world that will try to shove women into a box to make their differences acceptable—one must conform to something.

Let it be known, reader, that no woman—or anyone else for that matter—needs to conform to anything. The very idea of conformity has been fabricated from the start, since ‘woman’ and ‘man’ were conceptualized as separate genders rather than subsets of genetic phenotype. There is nothing to conform to, rules are made up, categories are for fun and magazine quizzes, not the great aggregate mass of human expression.

And “See You Again”, by Tyler the Creator and featuring Kali Uchis, is just a good song. Nothing more. Sing whatever part you want at the end. All it means for who you are is that you decided to sing it.

I send you off with a r/3amthoughts post that highlights the silliness of all this.

Additional citation:

0 notes

Text

Unsurprisingly, Movies Start Gender Conversations Also

Like many people, I went to see the Barbie movie in theaters. Solid movie, with a nice message I thought to be clear-cut and uncontroversial.

Boy howdy. Was I wrong.

(Spoilers for the movie beyond here, by the way)

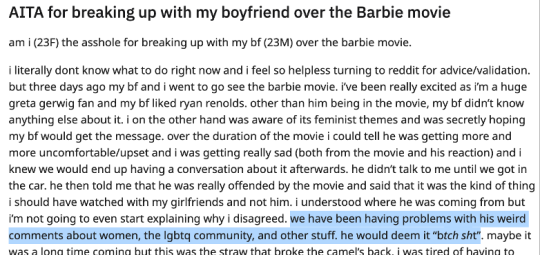

Aside from (justifiably) raving over the production value of the film, the acting, music, et cetera, watchers were also at each other’s throats after the movie concerning what it was about, and, more concerningly, who it was ‘for’. Some men (and women, sexism is a joint effort sometimes) in comments sections of Barbie-related posts complained of ‘anti-man’ sentiments in Barbie. They often get this from the plot: it revolves around Barbie and Ken going to the real world out of Barbieland, Ken seeing the patriarchy, admiring it, and copying it, transforming Barbieland from a strictly matriarchal model to that of a patriarchy—until Barbie puts it back the way it was before, right before she leaves to go live in the real world.

The Barbie matriarchy is a direct and more hyperbolic opposite to the patriarchy we currently live in. Women hold all the jobs, get all the awards, and men are hollow accessories who are only important as attachments to women. Kens do not have careers, dreams; Kens are Simply There. Some watchers were offended by this, despite it being satirical—neither a matriarchal or patriarchal Barbieland is ideal. The movie basically smacks you with the repeated notion that no one should be put down for their gender or have their worth judged for a stereotyped role they are forced into. Barbie’s trip into the real world overloads her with real-life oppression against women, and she recoils in horror and some jokes come of the absurdity of the patriarchal complications of living womanhood. Women familiar with it laugh, and some men aware of this reality get a laugh out of it too.

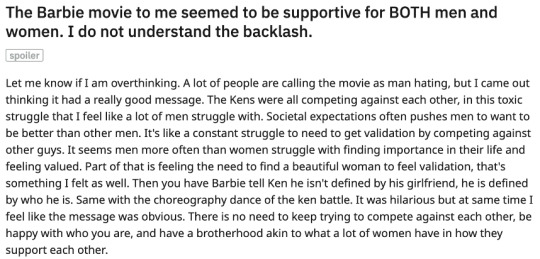

It was a jokey, palatably political movie about something most everyone knows about (if they don’t directly deny it). But the plot’s focus on barbie fostered a belief in some listeners that it wasn’t ‘for’ men to watch. Aside from the experiences of men also being a feature of the movie, as it’s reinforced that the reduction of identity Kens face (under the Barbieland matriarchy and satirized in the Ken patriarchy) is also a problem, the day-to-day experiences of men or other non-women like nonbinary folks are not as much of a focus.

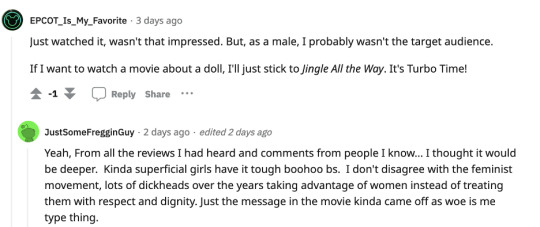

Does that mean the movie is not ‘for’ them? Many thought so:

What’s an audience in terms of media? Are messages for people, or to people?

I think they are both; a mix. Maybe not always in equal parts, but a mix nonetheless. However, a lot of the ‘who it’s for’ part of the conversation has molded into another set of gender stereotypes it seems.

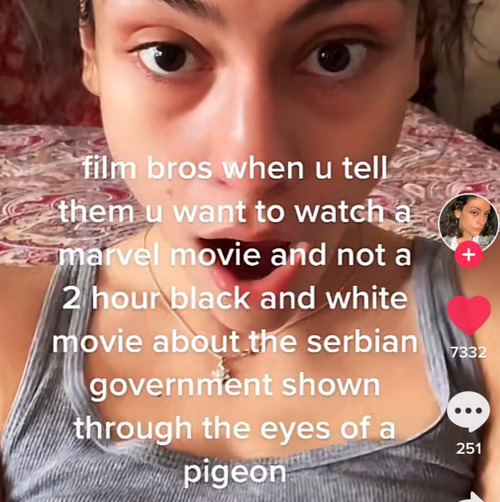

Take the case of ‘film bros’. This was at first a designation of dudes who, at the rise of the DVD, took to buying them and listening to all the commentary tracks and subsequently talked down to folks who didn’t know every single minute detail of production. It has since evolved into a category assigned to men who watch movies that some deem pretentious for their content. No longer does it always mean a man who talks down to someone about their interest (though that still definitely happens), it can mean something like this:

“Film bro” thus becomes merged with a category of movie.

Remember “chick flicks”? Seem familiar? It’s the same, sort of opposite. It also bears the unfortunate symmetry of assuming that male interests are inherently intellectual (even if it’s mocking them, that’s the association) and that women wouldn’t want to watch that sort of thing because thinking about movies is stupid.

Nobody wins here. Movies are not ‘for’ anyone in particular in the sense that only certain kinds of people want to watch them. Some may have common interests depending on personal taste. That’s completely normal. Sometimes it may follow lines of gender slightly—women might like a certain movie more than men in some cases, or vice versa, and that difference does not have to bear strange gender stereotypes as long as we do not assign that to them ourselves.

Multiple factors influence the enjoyment of media. Personality, taste in art, sheer random appeal of various elements—gender is a factor in how some trends may go because of how people raise their children differently, and how we treat men and women differently in society at large. It does not determine whether someone will watch Barbie and like it, or whether they like foreign movies that are esoteric and strange. Anyone can enjoy anything. It’s important to not let labels and stereotypes define who we let ourselves be and what we allow ourselves to enjoy—I’m sure a young girl out there somewhere would really love the Serbian government pigeon movie. Pigeons are cool.

0 notes

Text

Video Games and Gender

My first Christmas owning a console—a pink Nintendo DS Lite—I got a couple of game cartridges. Having only been on the sidelines of gaming, playing only at friends’ houses and seeing all sorts of cool games with magic combat, cool graphics, giant motorcycles and guns, I was hyped to say the least.

I got three games that Christmas: Moshi Monsters Moshling Zoo, Moshi Monsters Theme Park, and Chess for Kids. Cue immediate deflation. Why did I get the girl version of a monster collecting game? Moshi Monsters was an often girl-marketed game as far as I understood it. Games were toys, marketed with gender in mind just as often. It didn’t help that I also got one of those game t-shirts from the girls’ section—Pikachu was on it (wahoo!) but only along with a smattering of hearts and sparkles on pink. The “girl” stuff always had to be different. Even while playing the chess game, the UI needed to know whether I was male or female. That wasn’t my parents’ fault—nonetheless, I felt a bit boxed in.

Why was it so important to have a defined gender in these games? Why did the game often get to choose for me? Why did only types of games allow you to play as a girl (or have it as the only option) while some genres were entirely male player-characters (PCs hereafter)?

When I went over to my friend Derek’s house, I could see a world of games entirely different from mine. First off, there was the violence, always coming from male characters. I don’t think I actually ever saw a gender selection screen on any of his games, unless counting the rosters of fighters like Dragon Ball. We had Minecraft and Fossil Fighters in common of our personal game collections, and Fossil Fighters didn’t have a gender selection. Instead, you would choose your favorite dinosaur and get an outfit of its color scheme. You could be pink if you liked the Maiasaurus. Just not a girl. Fossil fighting was for boys, though ironically two other main characters and fighters are young women. (This was fixed in the second game).

There is a strange limitation in effect of many video games. Nowadays, there’s of course more variety—many games, especially role-playing games (RPGs) will offer a character creation bit or a vague gendered selection. Indie games are excellent with this, often taking care to even offer small bits like pronoun preference.

Many games do not have any choice at all, though, except maybe for name. Especially with earlier games in the 80s and 90s, you’d play as a set character or not play at all. And those characters were nearly unanimously men. Exceptions to the rule would usually be games where you could only play as a woman, which included things like Barbie. The content and genre of the games would vary widely based on the gender demographic. PCs were only men in shooter games or things like Grand Theft Auto. Games on average were more focused on adventure, yet had potential to branch out a lot. Boys could play in any sort of story. Except the Barbie games. Barbie games were Barbie games, and you could only be a blonde woman buying heels and calling her boyfriend. This was dating back to the times of the Commodore 64.

The concepts of video game adventures are generally pretty gender neutral. They end up supporting some stifling roles in limiting their adventures to male PCs when there is no reason to. Individual characters (like Ness of Earthbound, or Lara Croft of Tomb Raider) are a different case, as they place you into a single place rather than you being a random insertion into a universe. After a while, though, when you only hold an assault rifle in the hands of a male character and care for animals in that of a female character, there are implicit lines being drawn. Violence is for men. Caring is for women. Women play one role, men another. Binary, exclusive distinctions in the gender roles of characters are damaging, even if you might not take it to heart too much.

The binary is enforced in ways ranging from unnecessary to borderline nonsensical in video games. In the latest installments of the Pokémon game series, the character creation only asks “What do you look like?” with presentations of male and female character options, but if you choose a female character you will be referred to as “Mistress [Name]” by the school’s principal, and “Master [name]” if you play a male character. It’s the only difference, aside from visual, in the game from the player character’s appearance. I am also of the opinion that it is weird to call a school-aged person ‘Mistress’. Strange.

Another example from Pokémon (I play a lot of Pokémon) is a niche, still odd example found in a hidden sort of mini-dating sim in the White 2 and Black 2 versions of the game from 2012. Walking onto certain spots of the map after picking up a lost calling device triggers a series of phone call conversations. The gender and dialogue of the caller change depending whether the PC is a boy or girl. The caller is always the opposite sex: Yancy calls you if you’re a boy, and Curtis calls the girl character. Their dialogue not only differs in their personality…only the men get to talk about themselves! I’m not kidding. Though you can’t read any dialogue from the PC during the calls, if you’re a boy, Yancy only responds to what you say, barely (if ever) saying anything from herself. Curtis will talk your ear off.

Here’s examples of the differences between the same conversations, with the different callers:

Yancy:

Curtis:

It is as insufferable to play as it is to read. Though it’s silly looking, it still supports a standard of men always taking the initiative, and women being receptive conversation partners and always going off of or listening more to what the man is saying. There isn’t even a reason to really have this difference, as since the player has no dialogue options to choose, they can’t really talk about themselves. I wanted to hear Yancy’s favorite type of music too, but all she says is “I like music too!”. Horrible.

These kinds of arbitrary limits and differences are all over the place in games, and though they seem unserious sometimes at face value, they quietly (…or less quietly) reinforce “dos” and “donts” for players based on their gender. In Fire Emblem, only males can axe-wield until the fourteenth installment of the games. Men can’t be Pegasus Knights because they are considered too provocative for the skittish creatures…while literally all women are calm enough, apparently.

There are always arguments of gender differences in games being ‘realistic’, contributing to the suspension of disbelief in gameplay by anchoring mechanics to real world truths. The key takeaway I want you to have from reading this is that not a single gender difference is absolute in this world. Not a single one. There are trends—many people raise their children in separate ways, subtly or unsubtly, based on their assigned sex—in cultures, eras, geographical location, the list goes on. Nonetheless there always exist people outside of the standard. The standards of gendered behavior and general constitution are shaky at best, and fictitious at worst. Women are not inherently more receptive or docile, they are raised to be, so some may have more of that sort of personality by virtue of any sort of influence or personal disposition. They can also be literally anything else. Liking pink or blue, guns or glitter, pegasi or dinosaurs or whatever aren’t wired into anyone’s chromosomes, and neither are their personality traits for the most part.

The prevalence of these sort of tropes create an uncomfortable environment for many gamers that aren’t men that fit the bill of the expected audience. Men may not care as much that men and women’s stats have opposite strength profiles in Fire Emblem for the most part. A female player would likely not want to play games where she is at a set disadvantage solely for picking the character with eyelashes, or where choices are limited based on that initial character choice. Many people enjoy immersion in games, and when that immersion mimics and reinforces real life sexism, video games become understandably less attractive. If the only women in a game are sex objects, it’s not really as fun anymore to play as a woman, knowing that’s the place of women in the world of the game.

Unfortunately, these strange standards are mirrored onto playerbases quite often. Especially with chronically online gaming folks, the separation of the functions and abilities of men and women gets downright absurd, and can reinforce already prevalent misogynistic stereotypes. And with all that, some come to think: what women would even want to play games then?

Aren’t these just a dude thing?

And so the cycle continues.

People of all genders and backgrounds have infinite potential, on and offscreen. When games refuse to represent that--or worse, refuse its possibility outright by their mechanics--they perpetuate the cycle of restricting peoples lives by arbitrary elements of their identity.

0 notes

Text

TV Tropes and Condemnation

Media, especially visual media like videos and TV, often employs tropes to get audiences to recognize patterns in a message that’s being communicated. For example, sitcoms rely on viewers recognizing an awkward situation, dramatic irony, etc. to laugh when things go wrong or strangely. Horror media often employs tropey signals that a situation is dangerous; that someone will get hurt imminently. Those patterns, as you may guess by the general theme of this blogging profile, include the many patterns and tropes comprising gender and its associated systems of roles. Some shows will expect you to laugh simply because a male actor comes onstage wearing a dress—and reinforces it with a laugh track. It’s supposed to be funny. You are supposed to laugh because people are not supposed to do that; it’s a joke, as the laugh track tells you. What a silly moment, it says. We here at the show production studio think this is quite a funny bit. All those people in the track are laughing, so it is clearly funny to many people. Therefore: join in!

“Well, people would probably laugh at that in real life!” Maybe. But not all the time. It certainly isn’t an absolute. Nothing is, socially. Popular and expected reactions vary widely and define the social climate of any time and place. Laugh tracks are a light way of signaling the expectedly popular reaction: people will find this funny. That “aw” sound does the same thing with pity. Gasps work with shock. You know the deal. Onto the issue of gender.

When gender is performed in media, it is more often than not stifling and character-defining, and any deviations are either highly dramatized (A woman with short hair!! EVERYONE IS SCREAMING!!) or criticized (An adult man is a virgin! Oh no! Now the plot has to fix him!). Gendered standards are a framework that widespread phenomena like TV shows and movies use as a base for expected audience opinions and reactions. Factor in punctual laugh tracks, a cast of characters to reinforce the expected—or mandated—reaction, and you have yourself an informal instruction in how people will react to something. AKA: Whether you should do it or not—and what will happen if you do it anyway. Incorrect actions are signaled by laughter, ridicule, and criticism. If you don’t participate in this condemnation from beyond the TV screen don’t worry, the show will do it for you. As an implicit instruction. Characters who deviate are condemned by their show through transformation into a more agreeable performance of their genders or otherwise punished by the plot and its cogs. This more structural working does the same work that laugh tracks do, fit with more comprehensive signs that scream “Nope! Wrong choice!” with devices like character death,

When a minoritized person fights against the powers that be in a show (usually in the ‘wrong way’) and the show explicitly directs the powers that be to strike them down, the cast and implicit bias of the show chiming in…they expect you to root against that character. Bad things happen to good people, of course. However, the entire framing of a character leaning towards condemnation is something else. Characters drowned by plot weight and laugh tracks are messages, not favorites.

This is often the case for sitcoms and crappy horror movies in my experience. Women getting in ‘catfights’ are often a played-up situation in the former, and making ‘stupid’ or overly ‘neurotic’ decisions in the latter. Both personally tire me out and cause me to avoid the genres like plague in certain situations. These patterns supersede the media they directly appear in, however. The prevalence of reinforced gender roles (that is, reward for compliance and punishment for deviation) circulate back from media through the general social sphere. Of course, people do not learn or absorb their ideas of acceptable gender performance solely through their television, but it certainly contributes to and at times may reflect what is thought to be acceptable (it got on air, after all). People used to a binary that designates the same actions as vindicated on a man’s part and ‘bitchy’ on a woman’s will apply that judgement to their own life as well as the fictional ones presented to them. It can happen even when the show actually argues the opposite; people are often so used to the more condemning set of double standards that when complications are introduced, they are shoved away in favor of binary judgement. I’ve seen it myself. Don’t just take my word for it, though.

Take the case of Skyler White of Breaking Bad. The wife of Walter White, a man who turns to meth dealing to get money to treat his cancer. Without spoiling too much, to be frank, Walter treats her horribly. There’s huge struggle between the two as they handle the predicaments of the series separately, constantly clashing. They are similar people in a strange way, neither particularly good people, and both with immense flaws.

Skyler White was one of the topmost hated characters on TV for years.

The argument for this, as presented by The Guardian, speaks for itself:

“The general gripe was this: Walt was out doing whatever had to be done to provide for his family, while all she did was sit at home, moan and get in his way, right? Wrong. We didn’t know it back then – perhaps even Breaking Bad’s creator Vince Gilligan didn’t fully understand”

(" Skyler White: the Breaking Bad underdog who set the template for TV's antiheroine”)

It wasn’t that hard to tell, and the writer likely knew what was up when writing a companion to a man that regularly commits atrocities, but when TV is so heavily saturated with tropes and something doesn’t fit, it is sometimes easier to shove whatever is left into those neat boxes. When you have to wear a set of distorting goggles to understand the message of most TV shows, that distortion becomes the default and distorts everything else outside of it.

No one is immune to these implicit biases communicated to us constantly through the media complex. Not even me. Being concious of them is a major step towards dismantling these tropes, however, and minding how the fiction we curate reflects our understanding of character in the real world as well. Skyler’s actor faced endless harassment for simply doing her job acting for a fictional story.

For something to chew on, I leave you with the description of Skyler from earlier in the same Guardian article calling attention to Skyler’s foundational character typing….

“Still, there was a time when Walt’s priggish, perma-pregnant, party pooper of a wife raised the hackles like no one else, and her many Facebook hate pages accrued nearly 60,000 “likes” between them”.

Mind not only your words, but where they come from.

0 notes

Text

Unhinged Woman: BookTok, Genre and Gender

When you see ads for books—rare as they might be—where do you find what it’s about? How do you decide to pick it up? It depends on the kind of summaries you’re reading; what you want out of your read.

Many Americans born in the 90’s and 2000’s alike remember flipping through the Scholastic Book Fair catalog, reading through the tiny blurbs to decide what books to buy. Depending on the magazines and periodicals you’ve read, they still publish blurbs anywhere from a paragraph to a page long, fit with succinct phrase reviews to advertise the draw of a book. What happens when you try to condense that—a book’s central concepts—into a 20 second video?

TikTok’s explosion of popularity and effective streamlining of video content has presented an interesting new form of marketing. Everything from clothes and music to cigarette boxes and keychains has a set of keywords that can carry them into a subculture or niche of the social media platform. The condensation of book discussions is no exception, giving rise to the “BookTok” niche. Users show the books they have read along with their recommendations and short descriptions, ranging from individual recorded discussions to grouping reads by keywords and tropes. The latter has especially seen an explosion on the platform—I myself have scrolled past (on Instagram Reels) videoed stacks of books labeled with “enemies to lovers”, “slow burn”, “toxic romance”, “unhinged women”, et cetera.

It’s a pretty effective way of getting across a central function of the book’s plot across to people who enjoy a certain kind of trope. Books are neatly filed away into what they do for their readers, the kinds of character perspectives readers will immerse themselves in, and what to expect of the read. With the level of simplicity espoused by some corners of BookTok (and TikTok’s algorithm), though, categorization becomes quite literally the name of the game. In a digital world algorithmically naming aesthetics, tropes, and all sorts of presentations of art and the self, nothing is exempt from being named and graded on a keyword rubric.

When it comes down to checklists and keywords, it’s easier to see book-reading as a fulfillment of requirements. Readers become primed to look for nameable patterns in the books they read, deciding what they like by looking for a repetition of tropes in their next read. When they find a book they like, they can go on BookTok and find more books to narrow down their favorites into searchable phrases or advertise their own recent reads under a conveniently named list.

Pattern-focused consumption of media has very real drawbacks, though. When categorization dominates the search for more nuanced experiences, nuance takes a backseat as consumers filter out what they don’t want and see books for the sum of their most popular parts rather than a standalone work of writing. A book about a cannibalistic woman, regardless of her reasons or context, is one of a stack of ‘unhinged women’ books recommended by a video on the For You page. I genuinely came across this once when I had a TikTok account.

These microlabels assigned to books are not infallible. As the content can be interpreted in myriad ways, so can the categories they fall into. But let’s zoom in a bit and examine the mechanics of some of their consequences. When books focus on women with severe mental trauma/illness, morally fraught situations, or any kind of intense interiority, they are easily chucked into the ‘unhinged’ pile. This categorization is attractive to keyword-trained readers—and this categories is popular, especially because people find it relatable. It’s put perfectly into words by one blogger who, to paraphrase, writes that their enjoyment comes from seeing people like themself, and instead of being labeled ‘crazy, unhinged, mentally ill’ as accusations, they are able to reclaim their experience by embracing the identity of the ‘unhinged woman’. It is a comfort, and understandably so—women are constantly told they are crazy, with a much lower threshold of what constitutes ‘crazy’ than men. But this is also internalized to a high degree. Women often consider themselves to be mad as well, as the conditioning of woman as an ‘other’, unlike the man, and often the occupant of a role (daughter, wife, mother, etc.) places many restrictions on what they are “allowed” to be while still being considered a typical woman. Deviation from the role, inability to keep up with life without betraying the more deep-cutting aspects of human emotion and suffering, is more ‘unhinged’ when a woman is deviating rather than a man.

Referencing Phyllis Chesler’s “Women and Madness” Dr. Shoshana Felman writes on the intricacies of how woman’s failure to fulfill their assigned role is more easily classified as something absurd:

“From her family upbringing throughout her subsequent development, the social role assigned to the woman is that of serving an image, authoritative and central, of man: a woman is first and foremost a daughter/ a mother/ a wife. ‘What we consider 'madness', whether it appears in women or in men, is either the acting out of the devalued female role or the total or partial rejection of one's sex-role stereotype’” (Felman, Shoshana. “Women and Madness: The Critical Phallacy.”)

The “unhinged” woman is a wide subgenre. It ranges from the main character of Gone Girl to Fleabag to again, a literal cannibal, which I cannot get out of my mind. What really hits home about this category is that it is inapplicable to men with how society treats gender. Gender is not just a set of roles; it assigns personality stereotypes to people. As Chesler writes, “a woman is first and foremost a daughter/ a mother/ a wife” in the consideration of how many understand women’s participation/role in society—therefore, when a woman is primarily defined by something else in literature, especially anger, which is so heavily policed for women, it reads as particularly shocking and absurd. The kind of anger that is actually messed up, that results in the death of others, and is unapologetically violent and destructive reads to most, at the very least subconsciously, as unexpected, or simply less possible for women.

If these books and media had their ‘unhinged’ female characters replaced with men, I have a feeling they would be called something else. I leave you with this thought:

Have you ever heard people call Crime and Punishment an ‘unhinged man’ novel?

Do you think they would think to do that? What do you think would be different if they did? If more people did?

And what if being a man defined the story more than what the man did?

--- Citation below the cut ---

Felman, Shoshana. “Women and Madness: The Critical Phallacy.” Diacritics, vol. 5, no. 4, 1975, pp. 2–10. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/464958. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

0 notes

Text

Welcome/Testing Testing 123

Welcome to the blog. I'm the poster, and I use any pronouns. The blogs posts here are concerned with gender and digital media curation, the first post being soon to come (in the next week or so). Apologies for the blank space until then.

0 notes