Text

Soul-Stealing Picture Phobia

I've heard of the superstition that cameras steal someone's soul when a picture is taken. I'm not sure when or where this belief first took hold, but Journey to the West (Xiyouji, 西遊記, 1592) exhibits an example that predates the camera. Chapter 32 reads:

Among those thirty little fiends, there were some who did not recognize Eight Rules. There were a few, however, who found his face somewhat familiar, and pointing at him, they said, "Great King, this monk looks like the portrait of Zhu Eight Rules." The old fiend told them at once to hang up the picture so that they could examine it more closely. When Eight Rules saw it, he was greatly shaken, muttering to himself, "No wonder I feel somewhat dispirited of late! They have caught my spirit in this portrait!" (emphasis added) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 2, p. 101)

那三十名小怪,中間有認得的,有不認得的。傍邊有聽著指點說話的道:「大王,這個和尚,像這圖中豬八戒模樣。」叫掛起影神圖來。八戒看見,大驚道:「怪道這些時沒精神哩,原來是他把我的影神傳將來也。」

I'm sure a phobia of having one's picture drawn goes back even further.

Source:

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

the Buddha made 3 circlets; each were given to Monkey King, Black Bear Demon, and Red Boy by Guanyin. but Sandy & Pigsy are sometimes depicted with headbands too? do they actually wear them or is this a stylistic choice? are they the same as Monkey's?

I enjoy reading your articles and going back to them for references!

Thank you for the kind words.

Sand and Pigsy do not wear the circlets in the novel. I believe that look is based on Chinese opera. Circlets are often symbols of "martial monks" (wuseng, 武僧).

#Asks#Journey to the West#JTTW#Pigsy#Sandy#Sha Wujing#Zhu Bajie#golden headband#golden circlet#golden fillet#Chinese opera#Beijing opera

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sun Wukong's theft of immortal peaches

Here is an article on the origins of the immortal peach-stealing episode from Journey to the West. The Monkey King's theft is likely based on the respective stories of the Han-era trickster Dongfang Shuo (東方朔) and a magic white ape from Song-era material.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Queen Mother#immortal peaches#peaches of immortality#immortality#stealing is fun#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#Jade Emperor#Dongfang Shuo#magic white ape#white ape

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

The historical Zhu Bajie

My friend Irwen Wong of the Journey to the West Library blog wrote a lovely article about a historical monk named Zhu Bajie (朱八戒) that the pig-spirit Zhu Bajie (豬八戒) is likely based on.

#Zhu Bajie#Pigsy#Journey to the West#JTTW#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#Buddhist monks#Chinese Buddhism#Buddhism

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Does Red Boy Look Like?

I've written an article about Red Boy's (Honghai’er, 紅孩兒) description in Journey to the West for the benefit of artists and cosplayers. Fans of Lego Monkie Kid can compare it to the design for Red Son.

#Red Boy#Princess Iron Fan#Bull Demon King#Monkey King#Sun Wukong#Journey to the West#JTTW#Red Son#Lego Monkie Kid

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Crow's Nest Chan Master of JTTW

I am reading back through Journey to the West (Xiyouji, 西遊記) and was reminded of a strange, seemingly throwaway character who appears at the end of chapter 19, the "Crow's Nest Chan Master" (Wuchao chanshi, 烏巢禪師). He is described as an accomplished cultivator who lives in a juniper tree nest on Pagoda Mountain (Futu shan, 浮屠山), just beyond the border of Tibet (Wusicang, 烏斯藏). Zhu Bajie claims the master once asked him to jointly practice austerities, but the pig-spirit passed on the opportunity. Flash back to the present, and the pilgrims pass into his domain. After a brief chat, the Crow's Nest Chan master orally passes on the Heart Sutra (Xin jing, 心經) to Tripitaka.

There are two things that interest me about the Chan Master. The first is his magical abilities. Sun Wukong is offended by the monk but fails to hit him with his staff:

Enraged, Pilgrim lifted his iron rod and thrust it upward violently, but garlands of blooming lotus flowers were seen together with a thousand-layered shield of auspicious clouds. Though Pilgrim might have the strength to overturn rivers and seas, he could not catch hold of even one strand of the crow's nest (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 391).

This reminds me of an event from Acts of the Buddha (Sk: Buddhacarita; Ch: Fo suoxing za, 佛所行讚, 2nd-century), an ancient biography of the Buddha:

The host of Mara hastening, as arranged, each one exerting his utmost force, taking each other’s place in turns, threatening every moment to destroy [the Buddha, but] … Their flying spears, lances, and javelins, stuck fast in space, refusing to descend; the angry thunderdrops and mighty hail, with these, were changed into five-colour’d lotus flowers…” (Beal, 1883, pp. 152 and 153).

This points to the Crow's Nest Chan Master having great holy powers.

The second thing that interests me is that he is based on a historical monk, Niaoke Daolin (鳥窠道林, lit: "Bird's Nest" Daolin; 741–824). Here is his full biography from the Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde chuandenglu, 景德傳燈錄, 1004 to 1007):

Chan master Niaoke Daolin ... was from Fuyang in Hangzhou and his family name was Pan. His mother, whose maiden name was Zhu, once dreamt of the rays of the sun entering her mouth, after which she conceived. When the baby was born a strange fragrance pervaded the room, so the name ‘Fragrant Light’ was given to the boy. He left the home life at the age of nine and received the full precepts at the Guoyuan Temple in Jing (Jingling, Hubei) when he was twenty-one years old. Later he went to the Ximing Monastery in Chang’an to study the Huayan Jing (Avatasaka Sūtra) and the Śāstra on the Arising of Faith (Śraddhotpada Śāstra, Aśvagosa) under the Dharma Teacher Fuli, who also introduced him to the Song of the Real and Unreal, and had him practise meditation.

Once Niaoke asked Fuli, ‘Could you say how one meditates and

how to exercise the heart?’

Teacher Fuli was silent for a long time, so then the master bowed

three times and withdrew.

It happened that at this time Tang Emperor Taizong had called the

First Teacher in the Empire [Daoqin] of Jing Mountain to the Imperial Palace and Daolin went to pay him a formal visit, obtaining the True Dharma from him.

Returning south the master first came to the Yongfu Temple on

Mount Gu (Zhejiang), where there was a stūpa dedicated to the

Pratyekabuddhas. At this time both monks and laymen were

gathering there for a Dharma-talk. The master also entered the hall, carrying his walking stick, which emitted a clicking sound. There was a Dharma-teacher present from a temple called Lingying, whose name was Taoguang, and who asked the master, ‘Why make such a sound in this Dharma-meeting?’

‘Without making a sound who would know that it was a Dharmameeting?’ replied the master.

Later, on Qinwang Mountain, the master saw an old pine tree

with lush foliage, its branches shaped like a lid, so he settled himself there, in the tree, which is why the people of that time called him Chan Master Niaoke (Bird’s Nest). Then magpies made their nest by the master’s side and became quite tame through the intimacy with a human – so he was also referred to as the Magpie Nest Monk.

One day the master’s attendant Huitong suddenly wished to take

his leave. ‘Where are you off to then?’ asked the master.

‘Huitong left the home life for the sake of the Dharma, but the

venerable monk has not let fall one word of instruction, so now it’s a question of going here and there to study the Buddha-dharma,’

replied Huitong.

‘If it could be said that there is Buddha-dharma,’ said the master, ‘I also have a little here,’ whereupon he plucked a hair from the robe he was wearing and blew it away. Suddenly Huitong understood the deep meaning.

During the Yuan reign period (806-820 CE) Bai Juyi was

appointed governor of this commandery and so went to the

mountain to pay the master a courtesy call. He asked the master, ‘Is not the Chan Master’s residing here very dangerous?’

‘Is not your Excellency’s position even more so?’ countered the

master.

‘Your humble student’s place is to keep the peace along the

waterways and in the mountains. What danger is there in that?’

asked Bai Juyi.

‘When wood and fire meet there is ignition – the nature of thinking

is endless,’ replied the master, ‘so how can there not be danger?’

‘What is the essence of the Buddha-dharma?’ asked Bai.

‘To refrain from all evil and do all that is good,’ answered the

master.

‘A three-year-old child already knows these words,’ said Bai.

‘Although a three-year-old can say them, an old man of eighty

can’t put them into practice!’ countered the master.

Bai then made obeisance.

In the fourth year, during the tenth day of the second month of the reign period Changqing (824 CE), the master said to his attendant, ‘Now my time is up.’ And having spoken he sat on his cushion and passed away. He was eighty-four years old and had been a monk for sixty-three years.

(Textual note: Some say the master’s name was Yuanxiu, but this

is probably his posthumous name.) (Whitfiled, n.d., pp. 56-58).

Sources:

Beal, S. (Trans.). (1883). The Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king: A Life of Buddha by Asvaghosha Bodhisattva. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/foshohingtsankin00asva/mode/2up.

Whitfiled, R. S. (Trans.). (n.d.). Records of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume 2 - The Early Masters. Hokun Trust. Retrieved from https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Lamp2.pdf

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#Journey to the West#JTTW#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Tripitaka#Tang Monk#Tang Sanzang#Xuanzang#Zhu Bajie#Pigsy#Crow's Nest Chan Master#JTTW characters

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve been doing my best to find proper descriptions of the pilgrims’ appearances, but my search results are being frustratingly vague, and the novel itself has a habit of giving this information in small, dispersed increments (which I struggle to find)—not to mention one or two costume changes on Monkey’s end.

So, I must ask, do you have any reliable sources for the crew’s physical appearance?

(Sorry if you’ve been asked this before!)

Sun Wukong - https://journeytothewestresearch.com/2018/05/30/what-does-sun-wukong-look-like-an-artist-and-cosplayer-resource/

Zhu Bajie - https://journeytothewestresearch.com/2021/08/08/what-does-zhu-bajie-look-like-a-resource-for-artists-and-cosplayers/

Everyone's height and also Tripitaka's description - https://journeytothewestresearch.com/2023/04/17/how-tall-are-the-main-characters-from-journey-to-the-west/

Sha Wujing's face and early clothing - https://journeytothewestresearch.com/2018/03/24/the-origins-and-evolution-of-sha-wujing/

#asks#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Tripitaka#Tank Monk#Tang Sanzang#Xuanzang#Zhu Bajie#Pigsy#Zhu Wuneng#Sha Wujing#Sha Monk#Sandy#Journey to the West#JTTW#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hellooooooo~

I've just been doing some research, and one of my sources gave a frustratingly brief explanation to one of my questions about JttW. As you know, Monkey cannot swim because he is a rock. HOWEVER, he's constantly going back and forth to Ao Guang's palace at the bottom of the ocean with no apparent repercussions, which has always seemed wierd to me. That's why when this book:

mentioned that the reason he was able to go down there was because of some water repellent charm called the Bishui Jue, I was interested. Unfortunately when I try to look it up, all I get is stuff about Genshin Impact. Do you have any more information on it?

Apart from transforming into an an aquatic animal, Monkey has a couple of methods for traveling through water. One is the "magic of water restriction" (bishui fa, 閉水法). He first uses this to travel to the Dragon Kingdom in chapter three (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 133). The phrase only appears once in the entire book. The second is "opening a waterway" (kai shuidao, 開水道). He first uses this on his return trip to Flower-Fruit Mountain in chapter three (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 137). The phrase appears a total of six times in the entire book (ch. 3, 14, 49, 63, and 92).

The latter skill seems obvious; it's like a tunnel of sorts. The former is, I guess, an ability to repel water. I'm assuming both are from separate oral story traditions that made it into the finished novel.

#asks#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#magic#magic travel through water#travel through water#Chinese magic#Taoist magic#Daoist magic#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I was Reading journey to the West and I came to the part where Buddha made the deal with wukong Here's something that catches in my attention when wukong said he wanted to take over heaven Buddha openly mock him to my knowledge Buddha was worship as a nice and kind Buddhist but yet he openly mocked the monkey king I don't know if it was translation error or something so I want to hear your answer

It is not a translation error. The simple answer is that the novel humanizes divine figures, giving them all of the emotions of a normal person. Even Guanyin gets angry with and berates the Monkey King. For example in chapter 15 she says: "You brazen macaque, red buttocks of a village fool!" (我把你這個大膽的馬流,村愚的赤尻。). [1]

Note:

1) Yu (Wu & Yu, 2012) for some reason translates this as, "You impudent stableman, ignorant red-buttocks!" (vol. 1, p. 327)

Source:

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.) Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare JTTW Puppet Play

I am proud to host a guest post by @ryin-silverfish about a rare JTTW puppet play from Quanzhou, Fujian province, China. The play is roughly from the Yuan to early-Ming period, meaning that it predates the 1592 edition of the novel. There are parallels with the finished work, pointing to a possible influence, or at the very least, they borrowed from the same source. But there are many differences as well. The most surprising for me are:

Sha Wujing is the one who transforms into a white horse.

Erlang becomes one of Tripitaka's disciples after being demoted for flirting with a heavenly maiden.

An example of modern Quanzhou string puppetry depicting a battle between Sun Wukong and Princess Iron Fan.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Tripitaka#Sanzang#Tang Monk#Zhu Bajie#Sha Wujing#puppetry#puppet history#puppet#Quanzhou#Fujian#Chinese theater#zaju play#Journey to the West#JTTW#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#Erlang shen#Erlang

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buddhist Deities Exiled From the Western Heaven

My new article examines the reasons why three Buddhist deities from Ming-Qing vernacular Chinese literature are exiled from the Western Heaven.

Master Golden Cicada (Jinchan zi, 金蟬子) (a.k.a. Tripitaka, Tang Sanzang, 唐三藏) from Journey to the West (Xiyouji, 西遊記, 1592) - a Buddha disciple who is caught sleeping during the Tathagata's sermon.

Miao Jixiang (妙吉祥) from Journey to the South (Nanyouji, 南遊記, c. 1570s-1580s) - A Buddha disciple who kills a belligerent sage on the grounds of the Thunderclap Monastery.

Great Peng, the Golden-Winged King of Illumination (Dapeng jinchi mingwang, 大鵬金翅明王) from The Complete Vernacular Biography of Yue Fei (Shuo Yue quanzhuan, 說岳全傳, 1684) - An avian dharma protector who kills a stellar-spirit for farting during the Tathagata's lecture.

The article analyzes them together and notes parallels, even with concepts from Greek philosophy.

The motif might serve as a good idea for writers wanting to create an OC with an interesting backstory. I have, for example, previously used it to suggest a fictional origin for Sun Wukong as a hot-tempered Bodhisattva (see the 06-16-23 update here).

#Buddhist deities#Chinese fiction#Master Golden Cicada#Golden Cicada Elder#Journey to the West#JTTW#Miao Jixiang#Journey to the South#JTTS#Great Peng#Great Roc#Yue Fei#story idea#story motif

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there an archive where the first versions of the journey to the west can be found?

I have two posts (one article and one archive) about the late-13th-century JTTW. It is radically different than the standard 1592 edition that we all know and love. For instance, Zhu Bajie is nowhere to be found, and Sha Wujing's precursor only briefly appears as a monster.

This article describes the 17-chapter story (part of chapter eight is missing):

And this archive hosts an English translation:

#Journey to the West#13th century#oral storytelling#JTTW#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Sha Wujing#Monkey Pilgrim#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#Chinese mythology#Buddhism

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there! unsure if this has been asked before, but where is your header from?

I found the picture randomly on the internet. But as luck would have it, I actually met the actor in November 2023 during a yearly Monkey King Temple trip in Taiwan. Yuta Ishiyama is a Beijing Opera-trained Japanese actor who specializes in playing Sun Wukong.

Here he is holding his personal Great Sage idol in a procession.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#asks#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#JTTW#Chinese opera#Beijing opera

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP: Sun Wukong's Powers and Skills

I'm currently working on a comprehensive list of Sun Wukong's magic powers. Here is just a taste from chapters two to four.

Bold black = magic power

Bold red = acquired non-magic skill

Bold green = claimed magic power that is never actually demonstrated

Bold orange = inborn talent?

Ch. 2

Early education #1: human skills - “[H]e began to learn from his [senior immortal] schoolmates the arts of language and etiquette” (與眾師兄學言語禮貌) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 116).

- Note: We all know that Monkey failed his etiquette classes.

Early education #2: religious skills - “He discussed with them the scriptures and the doctrines; he practiced calligraphy and burned incense” (講經論道、習字焚香; i.e. ritual procedure) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 116).

Wukong’s knowledge of scripture and philosophy pops up a few times in the novel. For example, he subsequently becomes enraptured by Subodhi's lecture on the Dao and Chan (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 116).

Early education #3: gardening skills - “In more leisurely moments he would be … hoeing the garden, planting flowers or pruning trees” (閑時即...鋤園、養花修樹) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 116).

Immorality (1st category) [1] - This is achieved via oral formulas (口訣) and breathing exercises (自己調息) at prescribed times (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 120-121).

- The stipulated Chinese hours are before zi (12:00-14:00) and after wu (12:00-02:00) (i.e. noon to midnight) (子前午後). However, historical real world practice is reversed: after zi and before wu (i.e. midnight to noon).

Adeptness (i.e. quick learning) - “But this Monkey King was someone who, knowing one thing, could understand a hundred!” (這猴王也是他一竅通時百竅通) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 122).

First learns the “Multitude of Terrestrial Killers” (地煞數; a.k.a. “72 changes,” 七十二般變化) - This requires oral formulas (口訣, a.k.a. “oral spells,” 咒語) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 122).

- This sometimes requires a magic hand sign and a shake of the body (see below).

First attempt at “Cloud-Soaring” (騰雲) - Subodhi mockingly calls this “Cloud-Climbing” (爬雲) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 122).

First learns the “cloud somersault” (觔斗雲) - This requires a magic sign, an oral spell, a fist clinch, and a body shake (捻著訣,念動真言,攢緊了拳,將身一抖). It takes him 108,000 li (里) in a single leap (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 123).

- 108,000 li = 33,554 mi or 54,000 km [2]

Multitude of Terrestrial Killers (i.e. 72 changes) - This requires a magic sign (捻著訣) and an oral spell (咒語). He transforms into a pine tree (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 124).

Cloud somersault - He flies from the Western Continent to Flower-Fruit Mountain (i.e. from one side of the world to the other) “in less than an hour” (消一個時辰) (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 125).

First use of the “body beyond body” (身外身法; a.k.a. “magic of body division,” 分身法) (i.e. hair clones) - This requires chewing and a “change!” (變) command. Small clone monkeys are used to overwhelm and beat up a monster who is three zhang (三丈) (31.29 ft / 9.53 m) tall (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 128). [3] A passage explains:

- “For you see, when someone acquires the body of an immortal, he can project his spirit, change his form, and perform all kinds of wonders [出神變化無方]. Since the Monkey King had become accomplished in the Way, every one of the eighty-four thousand hairs on his body could change into whatever shape or substance he desired” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 128).

- 原來人得仙體,出神變化無方。不知這猴王自從了道之後,身上有八萬四千毛羽,根根能變,應物隨心。

Cloud somersault - He flies 30 or 50 monkeys and property (pots, bowls, utensils, etc.) home from captivity to Flower-Fruit Mountain (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 129).

Ch. 3

Martial arts (武藝) - He “teach[es his monkeys] how to sharpen bamboos for making spears, file wood for making swords, arrange flags and banners, go on patrol, advance or retreat, and pitch camp” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 131-132).

- 教小猴砍竹為標,削木為刀,治旗幡,打哨子,一進一退,安營下寨 …

Cloud Somersault - He flies east from Flower-Fruit Mountain over “200 li of water in no time” (霎時間過了二百里水面) to the Eastern Continent (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 131).

Blows a mighty wind (陣風) - This requires a magic sign (捻起訣來), an oral spell (咒語), and taking a deep breath (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 131-132). A poem states that it puts the world into chaos:

- Thick clouds in vast formation moved o'er the world;

Black fog and dusky vapor darkened the Earth;

Waves churned in seas and rivers, afrighting fishes and crabs; Boughs broke in mountain forests, wolves and tigers taking flight.

Traders and merchants were gone from stores and shops.

No single man was seen at sundry marts and malls.

The king retreated to his chamber from the royal court.

Officials, martial and civil, returned to their homes.

This wind toppled Buddha's throne of a thousand years

And shook to its foundations the Five-Phoenix Tower (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 132).

- 炮雲起處蕩乾坤,黑霧陰霾大地昏。

江海波翻魚蟹怕,山林樹折虎狼奔。

諸般買賣無商旅,各樣生涯不見人。

殿上君王歸內院,階前文武轉衙門。

千秋寶座都吹倒,五鳳高樓幌動根。

Body beyond body (i.e. hair clones) - This requires chewing and a “change!” (變) command. The small clone monkeys carry an armory’s worth of weapons (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 132).

Magic of displacement (攝法) - This is a spell that carries the weapon-laden monkeys on wind (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 132).

Monkey claims to have a number of supernatural powers:

- “I have the ability of seventy-two transformations. The cloud somersault has unlimited power. I am familiar with the magic of body concealment (身遯身, a.k.a. 隱身法) and the magic of displacement. I can find my way to Heaven or I can enter the Earth. I can walk past the sun and the moon without casting a shadow, and I can penetrate stone and metal without hindrance. Water cannot drown me, nor fire burn me” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 133).

- 我自聞道之後,有七十二般地煞變化之功,觔斗雲有莫大的神通;善能隱身遯身,起法攝法。上天有路,入地有門;步日月無影,入金石無礙;水不能溺,火不能焚。

Magic of water restriction (閉水法) - He travels to the Dragon Kingdom (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 133).

Super strength - He effortlessly toys with a 3,600 catty (斤) (4,682.61 lbs / 2,124 kg) battle fork and a 7,200 catty (9,365.23 lbs / 4,248 kg) halberd (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 134). [4]

Super strength - He lifts the 13,500 catty (斤) (17,559.81 lbs / 7,965 kg) iron pillar in the dragon treasury (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 135).

Opens a waterway (開水道) - He uses the magic of water restriction to return to Flower-Fruit Mountain (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 137).

First use of the “Magic Method of Modeling Heaven on Earth” (法天像地的神通), a 10,000 zhang (萬丈) (104,300 ft / 31,800 m) tall giant form - This requires bending over and screaming “grow!” [長!]. This form has:

- “[A] head like the Tai Mountain and a chest like a rugged peak, eyes like lightning and a mouth like a blood bowl, and teeth like swords and halberds” (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 138).

- 頭如泰山,腰如峻嶺,眼如閃電,口似血盆,牙如劍戟

Immorality (2nd category) - This is achieved by inking out his name from the ledgers of hell [生死簿子] (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 141).

Ch. 4

Cloud somersault - It is much faster than those of ordinary immortals (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 145).

Travel to heaven - Refer back to ch. 3-#6A (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 145).

First use of “three-headed and six-armed” (三頭六臂) war form - This requires a “change!” (變) command (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 155).

Staff multiplication - This is done millions of times over (以一化千千化萬) to face Nezha’s own countless weapons (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 156).

- The multitude of armaments are said to “clash like horned-dragons flying in the air” (cf. Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 156).

Body beyond body (i.e. hair clones) - This requires a “change!” (變) command. Monkey creates an autonomous decoy to distract Nezha while he slips behind him to land a staff blow (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 156).

Immortality (3rd category) - This is achieved via heavenly imperial wine (御酒, a.k.a. “Immortal wine,” 仙酒 and “juices of jade,” 玉液瓊漿) (Wu & Yu, vol. 1, p. 159, 165, and 167).

I'm currently on chapter 16, so it will take me a while to finish, especially since I'm simultaneously gathering info for several other articles, including mirrored essays for Zhu Bajie and Sha Wujing.

Once I've gone through all 100 chapters, I will put each instance of a particular power into its own category (transformation, super strength, hair clones/tools, etc.) and then analyze everything as a whole. The Google Doc containing the list of powers will be attached to the analysis.

This project was partly inspired by a previous effort made by @the-monkey-ruler.

I'm open to feedback.

Notes:

1) In place of using “layer” or “level,” I’m choosing to designate his various immortalities as “categories.” This is because a new layer of divine longevity or durability would surely be added for each immortal peach, elixir pill, or cup/jug of heavenly wine consumed. Hence, eating multiple peaches would be one category, eating multiple elixir pills would be one category, and so on and so forth.

2) It’s important to note that 108,000 li is a metaphor for instant enlightenment (see section III here). Therefore, power-scalers should not use any instance of this as a feat.

3) One zhang (丈) comprises ten chi (尺, a.k.a. "Chinese feet"), and during the Ming Dynasty, one chi was roughly 12.3 in or 31.8 cm. This makes one zhang 10.43 ft or 3.18 m (Jiang, 2005, p. xxxi).

4) During the Ming, one catty (jin, 斤) was 590 grams (Elvin, 2004, p. 491 n. 133).

Source:

Elvin, M. (2004). The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China. New Haven (Conn.): Yale University Press.

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Monkey King powers#Sun Wukong powers#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

The aforementioned five ornaments are sometimes combined with another item to form the “Six Ornaments” or “Six Seals” (Sk: Shanmudrā, षण्मुद्रा), each of which is associated with a Buddhist wisdom:

The yogic ornaments … are commonly classified as being six in number: (1) the skull-tiara, (2) the armlets, (3) the bracelets, (4) the anklets … (5) the bone-bead apron and waist-band combined … and (6) the double line of bone-beads extending over the shoulders to the breast, where they hold in place the breast-plate Mirror of Karma, wherein … are reflected every good and bad action. These six ornaments (usually of human bone) denote the Six Pāramitā (‘Boundless Virtues’), which are: (1) Dāna-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Charity’), (2) Shīla-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Morality’), (3) Kshānti-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Patience’), (4) Vīrya-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Industry’), (5) Dhyāna-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Meditation’), and (6) Prajñā-Pāramitā (‘Boundless Wisdom’). To attain to Buddhahood, and as a Bodhisattva to assist in the salvation of all living creatures, the Six Pramita must be assiduously practised (Evans-Wentz, 2000, p. xxv).

The most detailed source I’ve found reads:

a. The Bone Wheel

Vajradharma wears a bone wheel on his head. It is formed from a small bone circle that sits around the crown of the head, surrounded by a second, larger circle. The two circles are attached to one another by eight bone spokes. On each of the five spokes at the front, above the forehead, stands a dried skull that supports the jewel, which is the crest ornament. From the lower part of their jaws, looped chains and hanging decorative chains extend downward to the space between Vajradharma’s eyebrows and to the tips of his ears. One the back of each skull is a multicolored vajra with a crescent moon placed to the left. The deity’s long hair passes up through the hole in the middle of the inner bone circle and is tired in a topknot.

b. The Earrings

There are five parts to the earrings. There is a main circle of bone, which is like a bangle. From the bottom of the circle hang two smaller rings, each one attached to the larger ring above them by a semi-circle of bone.

c. The Necklace

The necklace is made of two strings of bones bound together with hair taken from both a corpse and a living person. At the front is a square central hub. The hub forms the base for a T-shaped triple vajra. There are to more triple vajras placed at the two points where the strings of the necklace reach the shoulders.

d. The Bracelets

The deity wears a bracelet on each ankle, wrist, and upper arm, making six in total. Each bracelet is made from two strings of bones that have been bound together. There are three vajras on each pair of bracelets, one at the knot in the upper string, one at the knot in the lower string, and one opposite the knot in the upper string.

e. The Brahmin’s Bone Thread

Next is the Brahmin’s bone thread, or investiture thread (yajnopavita). On the front of the body, above the novel, is a bone wheel with either right or four spokes. There are holes in four of the spokes and two parallels strings of bone pass through each of them. Two of these strings go over the shoulders, and two pass under the armpit. On each of these strings are two vajras on the shoulder and another two under the armpit, making eight in total. Sometimes there is a second bone wheel on the back, to which all the strings are tied; if not, all the ends of the strings are knotted together.

Together, or with the thread of hair from a slain thief, these bone ornaments are called the ornaments of the five mudras.

f. The Bone Belt

The bone belt, or apron, hangs from the waist. It is made, as before, of two parallel strings of bone. The strings have five vajras attached to them–one at the front in the center, one on each hip, and one on each side of the center, halfway to the whips. Hanging chains and looped chains decorated with small silver bells and small bone spearheads hang from the tips of the vajras. The chains end at the point where the calf muscle begins to taper.

According to oral tradition, the necklace we just mentioned is ornamented with five vajras at the heart. Although I have consulted many descriptions of the bone ornaments, I have never seen this stated anywhere else. There are many traditions concerning the bone ornaments, but here I have presented that of the oral tradition taught by my master (Lingpa, Rinpoche, & Chemchok, 2017, pp. 52-54).

As can be seen, the tiger skin is not mentioned among these ornaments either.

Also, as is mentioned, the items making up the six ornaments vary from tradition to tradition. For instance, Huntington and Bangdel (2003) list bone ash in place of the bone thread (p. 161). But it’s important to note for our purposes that the circlet, bangles, bracelets, anklets, and belt make up the five basic accoutrements.

One example of the "skull-tiara" or "bone wheel" (i.e. the ritual headband) mentioned above looks like this.

A 19th-century Tibetan bone headband from the Art Gallery of NSW.

A drawing of Monkey wearing the bone ornaments would be great.

Sources:

Evans-Wentz, W. Y. (Ed.). (2000). Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa: A Biography from the Tibetan Being the Jetsun-Kabbum Or Biographical History of Jetsun-Milarepa, According to the Late Lama Kazi Dawa-Samdup’s English Rendering. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, USA.

Huntington, J. C., & Bangdel, D. (2003). The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. United Kingdom: Serindia Publications.

Lingpa, J., Rinpoche, P., Chemchok, K. (2017). The Gathering of Vidyadharas: Text and Commentaries on the Rigdzin Düpa. United States: Shambhala.

More on the Origins of Sun Wukong's Golden Headband

I've previously suggested that the Monkey King's golden headband (jingu, 金箍; a.k.a. jingu, 緊箍, lit: “tight fillet”) can be traced to a ritual circlet mentioned in the Hevajra Tantra (Ch: Dabei kongzhi jingang dajiao wang yigui jing, 大悲空智金剛大教王儀軌經, 8th-century). This is one of the "Five Symbolic Ornaments" or "Five Seals" (Sk: Pancamudra, पञ्चमुद्रा; Ch: Wuyin, 五印; a.k.a. "Five Buddha Seals," Wufo yin, 五佛印), each of which is associated with a particular Wisdom Buddha:

Aksobhya is symbolised by the circlet, Amitabha by the ear-rings, Ratnesa by the necklace, Vairocana by the hand ornaments, [and] Amogha by the girdle (Farrow, 1992, p. 65). [1]

輪者,表阿閦如來;鐶者,無量壽如來;頸上鬘者,寶生如來;手寶釧者,大毘盧遮那如來;腰寶帶者,不空成就如來。

Akshobya is known to have attained Buddhahood through moralistic practices (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 27). Therefore, this explains why a headband would be used to rein in the unruly nature of a murderous monkey god.

The original Sanskrit Hevajra Tantra calls the circlet a cakri (चक्रि) or a cakrika (चक्रिका) (Farrow, 1992, pp. 61-62 and 263-264, for example), both of which refer to a "wheel" or "disc." The Chinese version uses the terms baolun/zhe (寶輪/者, "treasure wheel or ring") and just lunzhe (輪者, "wheel" or "ring").

One of the more interesting things I've learned is that these ornaments were made from human bone. One source even refers to them as "bone ornaments" (Sk: asthimudra, अस्थिमुद्रा) (Jamgon Kontrul Lodro Taye, 2005, p. 493, n. 13). [1]

Can you imagine Sun Wukong wearing a headband made from human bone?! How metal would that be? Finger bones would probably do the trick.

Note:

1) Another section of the Hevajra Tantra provides additional associations:

The Circlet worn on the head symbolises the salutation to one's guru, master and chosen deity; the ear-rings symbolise the yogi turning a deaf ear to derogatory words spoken about the guru and Vajradhara; the necklace symbolises the recitation of mantra; the bracelets symbolises the renunciation of killing living beings and the girdle symbolises the enjoyment of the consort (Farrow, 1992, p. 263-264).

謂頂相寶輪者,唯常敬禮教授阿闍梨及自師尊;耳寶鐶者,不樂聞說持金剛者及自師尊一切過失、麁惡語故;頸寶鬘者,唯常誦持大明呪故;手寶釧者,乃至不殺蠕動諸眾生故;腰寶帶者,遠離一切欲邪行故。

2) For more info on the association between Hindo-Buddhist practices and human remains, see "charnel grounds".

Sources:

Farrow, G. W. (1992). The Concealed Essence of the Hevajra Tantra: With the Commentary Yogaratnamālā. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Jamgon Kontrul Lodro Taye (2005). The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Six, Part Four: Systems of Buddhist Tantra (The Kalu Rinpoche Translation Group, Trans.). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion.

#headband#ritual headband#esoteric buddhism#monkey king#sun wukong#bone ornaments#yogi#buddhist yogi#journey to the west#jttw#lego monkie kid#lmk

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

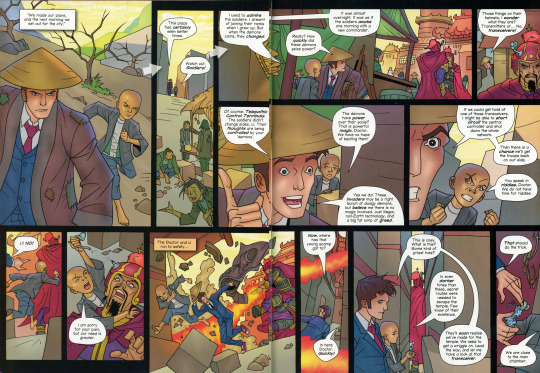

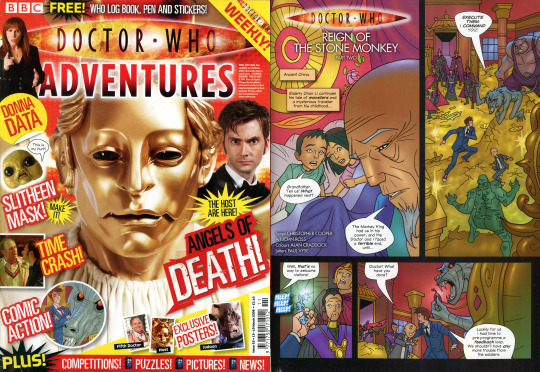

Doctor Who vs Sun Wukong

In December of 2023, a fellow member of the now private Monkey King Facebook group posted a link to this fandom article mentioning a two-part comic book story called "Reign of the Stone Monkey." It appeared in issues no. 54 (6–12 March 2008) and no. 55 (13–19 March 2008) of Doctor Who Adventures magazine. As a once passionate Whovian, I dutifully tracked down copies of the publication just so I could read it. I have attached scans below. Here is a PDF of the comic for anyone who wants to share it externally.

I must point out that the magazines are quite large and challenged even my A3-sized flatbed scanner. Therefore, parts of the pages were chopped off in places. You'll twice notice a vertical white line while reading. This was the result of me not being careful enough and a little too much was cropped. The white line maintains the correct spacing.

Anyway, back to the comic. To be frank, it is terrible beyond words. I think the editorial decision went something like this:

Editor: [Watches the trailer for The Forbidden Kingdom movie on TV] Wow! Jackie Chan and Jet Li? We better jump on this Monkey King thing, too.

Hey, writer ...

Writer: Yeah, boss?

Editor: ... your brother is married to an "Asian," right?

Writer: I guess. She's Filipino.

Editor: Close enough for me. I want you to whip up a script for a 10th Doctor versus the Monkey King comic book story.

Writer: The monkey what?

Editor: Just google "Monkey King." I want a script on my desk in ten minutes.

Beyond the bad story, the art direction is terrible as well. Instead of containing the action to the panels of a single page, it spills across to the other, making it difficult to read. The layout is so bad that translucent arrows are added to guide the reader's eye.

#Stone Monkey#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#Zhu Bajie#Pigsy#Sha Wujing#Sandy#Doctor Who#The Doctor#Tenth Doctor#Doctor Who Adventures#JTTW#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there an English translation of JttW that you consider definitive, or just personally recommend over others? Sorry if you've been asked this a million times!

See my previous answer.

I have numerous foreign language translations of the novel available here.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#Journey to the West translation#JTTW#Lego Monkie Kid#Anthony C. Yu#W. J. F. Jenner#translation#Tripitaka#Tang Monk#Tang Sanzang#Zhu Bajie#Zhu Wuneng#Pigsy#Sha Wujing#Sha Monk#Friar Sand

41 notes

·

View notes