Text

Chapter 18 Reflection

This course has been really enjoyable, enlightening, and empowering and I am sad to see it end! It’s been a very interesting time to study economics and I look forward to at least one more course in microeconomics, hopefully this Fall. Would that be the study of market behavior? It’s hard to pick out one concept or theory that was most useful. Overall, I would say that Chapter 11, which covered the Federal Reserve- it’s history, goals, and tools- really answered a lot of questions for me. It was previously a vague entity in my mind, but understanding now what exactly the Fed can and can’t do has made me, at the very least, feel like a more informed citizen. Figure 4 in Chapter 12 on page 243 showed some fascinating graphs of what hyperinflation can look like and I really enjoyed gaping at the four Eastern European economies depicted there. Chapter 8’s Figure 5 which depicts US government debt from 1791-2011 was really interesting, also. In fact, most of the charts and figures offered were incredibly helpful and I would love to see the updated versions of all of them in the next edition of this textbook. There are so many delightful little cliffhangers since this book was published before the Covid-19 pandemic. It was be a treat to see what Mankiw has to say on all of these topics in light of the recent economic turmoil that we’ve been through. This last chapter, as well, that covered the pros and cons of six major macroeconomic debates was very informative. I wish I didn’t have to return this textbook next week because I would like to be able to refer back to this chapter in particular when reading about future economic policies in the news. My thinking was changed throughout the entirety of the course! Most recently my thinking has been challenged on tax reform. I still think that taxing the pants off the ultra wealthy could solve a lot of our economic inequality, but it seems much easier said than done. Especially after our professor’s insight into the intricacies and difficulties with taxing wealthier and after reading this last chapter. The two debates that I thought most important and interesting were the debate over balancing the government’s budget and the debate over tax reform to encourage saving. It seems that, throughout my lifetime in which interest rates have been on the decline or just kept incredibly low, that there’s never been any incentive for my generation to save money. Coupled with a double boom in the housing market and the cost of living, it has seemed just damn near impossible to save for most people around my age. It feels like maybe the two go hand in hand- incentivize saving and balance out our massive government debt. The issue of government debt has seemed to just been treated like a can kicked down the road for some future generation to deal with. As I mentioned in the Chapter 17 Reflection, there are so many issues at hand that have come from this short termist approach to everything in out country. I’m not sure if I’m articulating myself very well, but the kick-the-can approach that policy makers have used over the last 60+ years is starting to feel like there’s not much road left to kick the can down. Even the textbook’s argument against balancing the government’s budget sounded pretty weak and unjustifiable to me. I’m not sure what the answer is to any of these looming economic, environmental, educational, public health and safety, social justice and equality issues is. After taking this course, though, it feels like increasing access to this information, educating the public to be more conscious participants instead of blind reactionaries, would be a good first step.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 17 Reflection

The short run trade-off between unemployment and inflation as described by the Phillips curve is a negatively correlated relationship. That is, when unemployment numbers are high, inflation is low and vice-versa. According to mid-century English economist A. W. Phillips, in years with high unemployment rates, inflation was relatively low. American economists of Phillips’s time, Robert Slow and Paul Samuelson backed up his research with similar findings of their own in the US economy. The sense here being that, when unemployment numbers are low, or a greater number of citizens are working, more money is being generated and passed around. More money in an economic system generally leads to higher prices or inflation. Conversely, when unemployment is high, or more citizens are out of the workforce, the amount of money in the system is depressed, meaning inflation rates run lower. This theory, however, does not hold up in the long run. As described by both Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps about a decade after the discovery of this short-run relationship, monetary policy cannot, in the long run, reduce unemployment by raising inflation nor vice-versa. Classical theory and monetary neutrality both point to why this is the case. As stated in our textbooks, “…monetary growth does not affect real variables such as output and unemployment; it merely alters all prices and nominal incomes proportionately” (p.369). Friedman points to the existence of a vertical long-run Philips curve that describes higher or lower inflation rates along the consistent, natural rate of unemployment. I think that there has to be a trade off, in the short-run, because we have real world examples of it. However, I agree with Friedman and Phelps that there isn’t much of a trade-off in the long-run. According to Friedman, the “short-run” can describe a period of anywhere from two to five years (p.386) and I agree with this view. Due to many factors- how long policies can take to implement and the amount of time it takes before we see actual impacts, sticky wages and prices, the confusion brought on by unexpected inflation- it is really hard to nail down exactly what constitutes a short-run. However, the short-run in economic terms is usually much longer than any media outlet will lead one to believe. I think that an antsy population with little to no understanding of how long economic trends take to unwind and understand has led to too many politicians running on very short-termist platforms which has led us to all the kinds of trouble that we are experiencing now; in terms of environmental problems, social justice issues, massive economic inequality, a poorly educated populace, etc. Is our current rate of inflation helping to reduce unemployment? I honestly have no idea. If this graph from the Bureau of Labor Statistics is correct, then yes:

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

It appears that unemployment has been decreasing in the US since it’s spike of around 8% in 2020. Unemployment numbers have gone down, but according to this graph from the US Inflation Calculator, inflation has also been decreasing; so far this year down 2-3% from its high of around 8% last year:

https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/current-inflation-rates/

If President Biden is able to enact his proposed Inflation Reduction Act, though, and if everything that we’ve learned so far in this course is true, then I can’t see how injecting more money into the economy and creating more jobs will actually reduce inflation. However, I am not an economist and, as mentioned previously, I think that these things will take years to play out before we are able to see and understand the full implications. It is, at the very least, a really interesting time to be learning about economics!

0 notes

Text

Chapter 16 Reflection

Based on the article shared with us earlier this month, “What Did the Fed Do in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic?” put out by the Brookings Institute, the Fed did so much to lessen the affect(s) of the pandemic on the economy (https://www.brookings.edu/research/fed-response-to-covid19/). They eased monetary policy by cutting the federal funds rate; used “forward guidance” to communicate future monetary policy and build confidence, or at least, provide a vague outline to investors and consumers; and resumed quantitative easing by buying back large amounts of government backed debt. The Fed also supported financial markets by lending to securities firms and backstopping money market mutual funds by relaunching the “Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility” which lent money to mutual funds that were having a hard time meeting depositors withdrawals. The Fed also encouraged banks to lend by loaning money to banks directly and by relaxing regulatory requirements, allowing banks to use reserves that were just waiting for such “rainy day” conditions. The Fed also made it possible for small and mid-sized businesses to access emergency loans, as well as state and municipal governments. Because these actions were all carried out by the Fed, they would be examples of monetary policy, tools that the Fed can use to affect interest rates and the money supply. I feel like I’m only really scratching the surface here of all that the Fed did in response to the pandemic to keep the US economy from total disaster. This was combined with the government’s various fiscal policies that were passed in a similar effort. All together, there were four stimulus and relief packages passed (though the last one is deemed 3.5) between March 6th 2020 and April 24th 2020 (https://www.investopedia.com/government-stimulus-efforts-to-fight-the-covid-19-crisis-4799723). I would say that their combined efforts were successful seeing as the US economy did not completely tank in the face of the global pandemic. However, such expansionary policies may be responsible for current economic conditions, namely, the inflationary cycle we have been in for the last year and a half now. In response to higher inflation, which began in mid 2021, the Fed has been increasing interest rates by .25-.5 percentage points over the last year. Since it’s only been one year since the Fed began raising interest rates, we are only now just starting to feel the effects. I can’t say that they have been successful or unsuccessful so far as it is still too early to tell. As far as the government and any fiscal action that they might take, I have no idea if they have done anything in response to inflation. Theoretically, the government could raise taxes, which would help suck some of the excess money out of the system, but I have not seen nor heard any hint of this happening. What politician is going to successfully run on a platform of raising taxes? On top of that, while everyone is struggling to make ends meet due to inflation, no voter is going to happily start paying higher taxes. If only there was some magical way to get citizens making over $250k/year to pay higher taxes… if only the wealthiest citizens among us could be persuaded to pay a fairer amount of taxes proportionate to their absurdly and unnecessarily high earnings so that they rest of us might be even just slightly better off… Unfortunately, I can’t ever see that happening in our country. The wealthiest members of the US economy also hold the most sway over fiscal policies that would reduce such massive inequality by charging them a higher tax rate. I feel that, in order to amass such amounts of wealth and gain such disproportionate amounts of power, these folks can’t have been the most civic minded to begin with. And, if I know anything about humans by now, it’s that, for all of our technological and societal advances, our brains have not evolved all that much from our days on the African Savannah. That being said, we are biologically wired to be greedy, to hoard resources beyond our immediate and even foreseeable future needs. How would you reason with a monkey sitting atop a 3 ton pile of bananas? How would you convince the monkey that it couldn’t possibly eat even a fraction of all of those bananas in its lifetime and that many more monkeys could be made better off if only it would give up 1 ton of its banana pile? Let’s say that it’s even a pretty smart monkey that has a small band of monkeys working for bananas to keep the 3 ton pile safe. How in the world do you reason with greedy, scared, overprotective monkeys?

0 notes

Photo

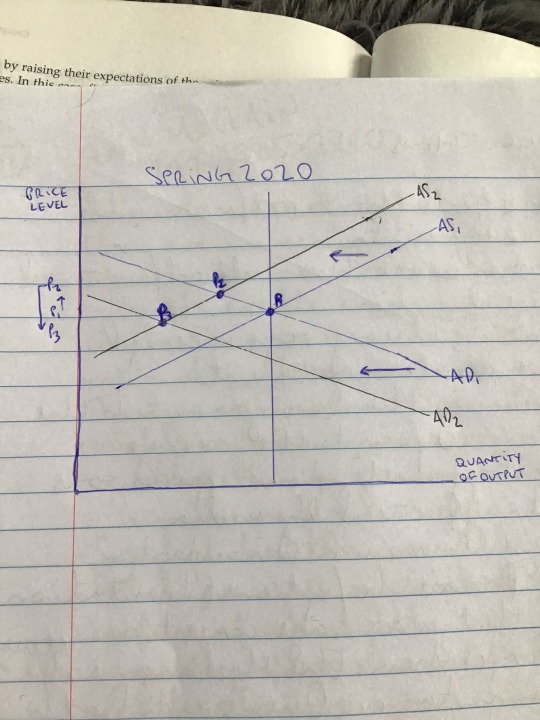

CHAPTER 15 REFLECTION

I’m not sure if I’m drawing this correctly on the graph, but after the initial shift in AS to the left, the price level along the original demand curve increases from P1 to P2. However, after the AD1 also shifts to the left to AD2, the price level (P3) drops to just below the original P1. As expected, the original shift in AS1 to AS2 in the Spring of 2020 did indeed result in higher prices, as I recall. I would expect that the short and long run are related in that prices will naturally rise over time. This adds up as every year, prices slowly creep upwards to adjust for inflation. From 1960-2021, the annual inflation rate was 3.8% (https://www.worlddata.info/america/usa/inflation-rates.php). I would expect that, after the initial spike in prices from P1 to P2, P3 would fall to just above the original P1 since I have never seen anything get any cheaper over the long run in my lifetime. As far as how long I would expect a short run to be, I would assume that the “short run” couldn’t be any shorter than 2 years nor any longer than 4 years. I suspect that the new long run equilibrium would be at a higher level, again, because, outside of the Great Depression and the Great Recession, we have only ever experienced an increase in prices over the long run. Now thinking of Spring 2023, I can only assume that SRAS has shifted back to, at least, close to our long run aggregate supply (I can’t find the current information online, what should I be searching for to procure this info?) According to this Wikipedia page about the recent bout of inflation (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021%E2%80%932023_inflation_surge): “A worldwide increase in inflation began in mid-2021, with many countries seeing their highest inflation rates in decades. It has been attributed to various causes, including pandemic-related economic dislocation, supply chain problems, and the fiscal and monetary stimuli provided in 2020 and 2021 by governments and central banks around the world in response to the pandemic were also instrumental. Unexpected recovery in demand through 2021 ultimately led to historic and broad supply shortages (including chip shortages and energy shortages) amid increasing consumer demand.”

So it sounds like our AD2 would have shifted back to at least AD1 levels. However, I would imagine that the AD curve would shift to the right again in response to inflation’s higher costs. As far as AS goes, I’m not sure if we have recovered to “normal” aggregate supply levels. The war in Ukraine and the US's decoupling from China would lead me to believe that we have not recovered to AS1. This adds up in my mind as we are still experiencing higher price levels. So, in terms of my predictions for price level and GDP growth over the next year, it looks bleak at best. The Fed only began raising interest rates to combat inflation one year ago and, from everything that I’ve read, we are only now starting to see and feel the effects of this tightening. I assume it will take at least another year before price levels begin to reach equilibrium. I’ve come to these conclusions by reading this newsletter sent out by Bridegwater Associates, a hedge fund that my partner follows- https://www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/an-update-from-our-cios-the-tightening-cycle-is-beginning-to-bite

0 notes

Text

Chapter 14 Reflection

The article that I chose to use for this reflection came from the Financial Times’ “Swamp Notes” series, a dialogic newsletter concerned with the interplay of money, power, and US politics. The link to the article is below:

https://www.ft.com/content/77e382a7-6a2a-4e42-af19-c34275ce3137?accessToken=zwAAAYdxzjL3kc9344KnaipOQtOvGcNCdc4xNw.MEUCIQD2nI_ShVOVcbqOGycWpK2VGzNrV_RF95fTWhaOrU7kuwIgK0xu1IlKJV5QJiomRVZGJKoMUYyolc2pN5rq6839k5Q&sharetype=gift&token=96a98b23-b0aa-4d15-964a-851ecedcfece

The author is Rana Foroohar and I largely agree with her perspectives. In this article, she reports on a speech made last week by US Trade Representative Katherine Tai about the future of US trade policy. I agreed with Foroohar mostly because I agreed with what Tai proposed- a sensible, flexible, open approach to “how domestic economic concerns and foreign policy concerns should be knitted together”. The four key takeaways that Foroohar presents from Tai’s speech are:

“This isn’t about keeping China down. It’s about using America up.” “Industrial policy and trade policy must work hand-in-hand.” “Neoliberal/Neoclassical economic modeling has too often assumed that markets are perfect. They aren’t and they need more active tweaking by the government.” “Yes, we need a new trade alliance in Asia to compete with China. But not if it sells out US labor or puts the green transition at risk.” “Resiliency and redundancy trump efficiency. We need to move away from concentrations of power be they in countries or companies.”

To me, this all sounds fair, logical, and practical. I think that de-emphasizing some kind of “imminent” conflict with China is ridiculous fear mongering peddled by the media. Why the two countries shouldn’t be able to coexist and pursue their own agendas (as long as the agenda isn’t war mongering, I’m looking at you US) is beyond me. Secondly, as pointed out in our text books on pages 298-299 (“In the News: Separating Fact from Fiction”), trade policy should be more closely in step with industrial policy. Instead of constantly looking to blame foreign countries for our problems, how about facing up to some of our own problems here at home? Thirdly, it is absurd that economists rely so heavily on models of perfect markets. It seems like a constant fallacy in the US that we don’t legislate proactively. We have a tendency to wait until problems blow up in our face to act instead of trying to prevent them in the first place. Next, we will have to compete with China but why should we sacrifice our environment or workers to do it? Why can’t competition be healthy for both countries and lead to higher standards for everyone? And lastly, we know by now that power tends to corrupt. Making a shift away from high concentrations of power in any system seems like a proactive move then. Trade deficits/surpluses are inextricably linked to capital flows. After copying each model in Chapter 14 of our textbook, it became clear that an economy’s net capital outflow determines how much of a country’s currency will be available on the foreign-currency exchange market. It also plays a role in determining the demand for loanable funds in a country's market for loanable funds. The relationship between a government budget deficit and a trade deficit is nicely summed up on page 291 of our textbooks: “Hence, in an open economy, government budget deficits raise real interest rates, crowd out domestic investment, cause the currency to appreciate, and push the trade balance toward deficit.” (Mankiw) The US does owe money to countries with whom we also have a trade deficit, China being the largest and most glaring example. Currently, the US trade deficit with China stands at $382.9 billion according to this New York Times article: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/07/business/economy/us-trade-deficit.html. China also owns about $870 billion of US government debt (from https://www.thebalancemoney.com/u-s-debt-to-china-how-much-does-it-own-3306355) Another example would be Japan. If you look at the graph at the top of the page linked above, Japan is the largest holder of US government debt with a whopping $1.08 trillion. Likewise, the US is running a trade deficit with Japan at $60.2 billion as of 2021 (https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/technology-evaluation/ote-data-portal/country-analysis/2982-2021-statistical-analysis-of-u-s-trade-with-japan-public-version-ote/file). It is beyond me how the US government continues to operate under such weighty debt, both in the trade of goods and services and financially. Does anyone ever talk about repaying any of the debt? I only ever hear about raising the debt limit.

0 notes

Photo

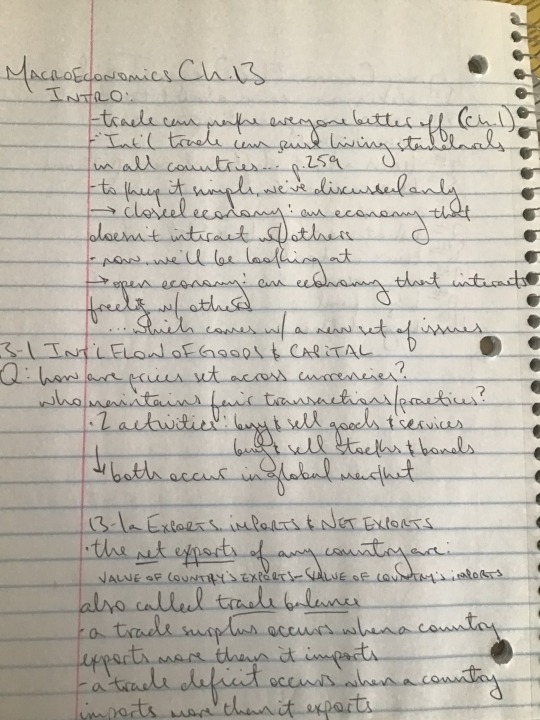

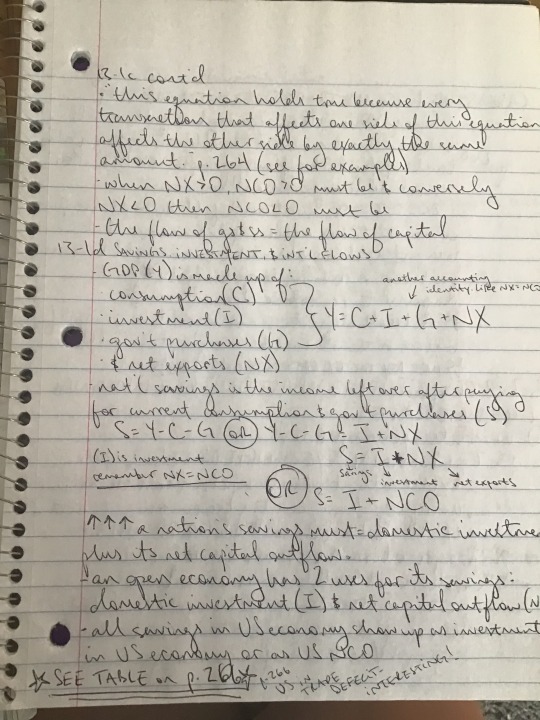

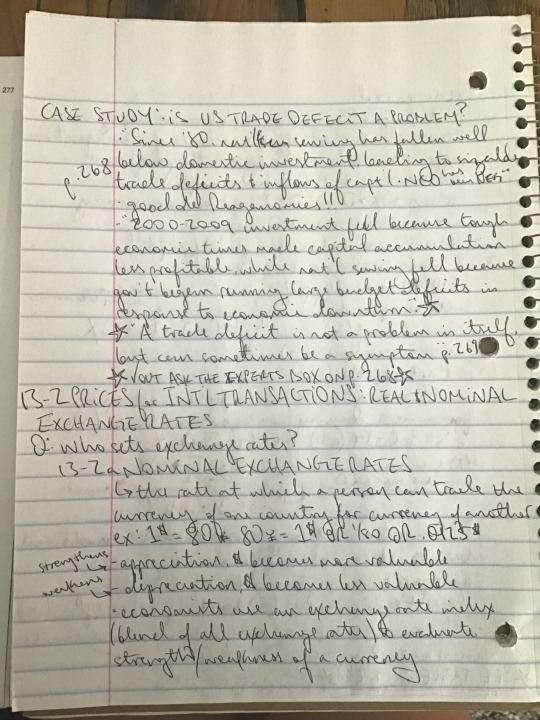

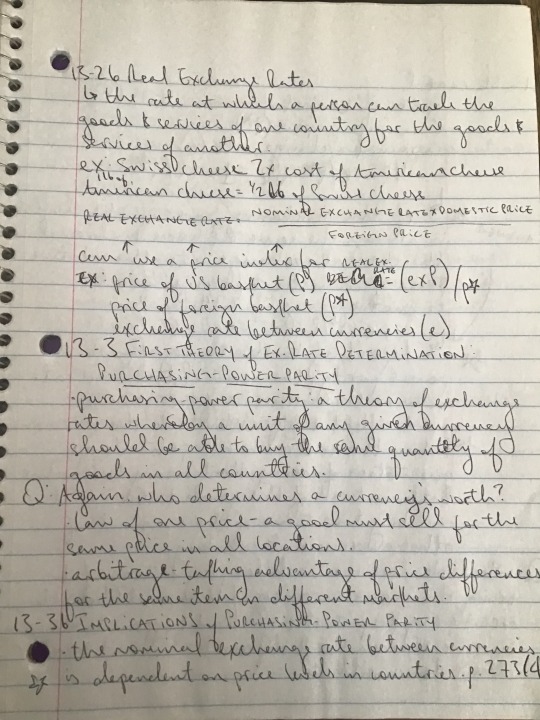

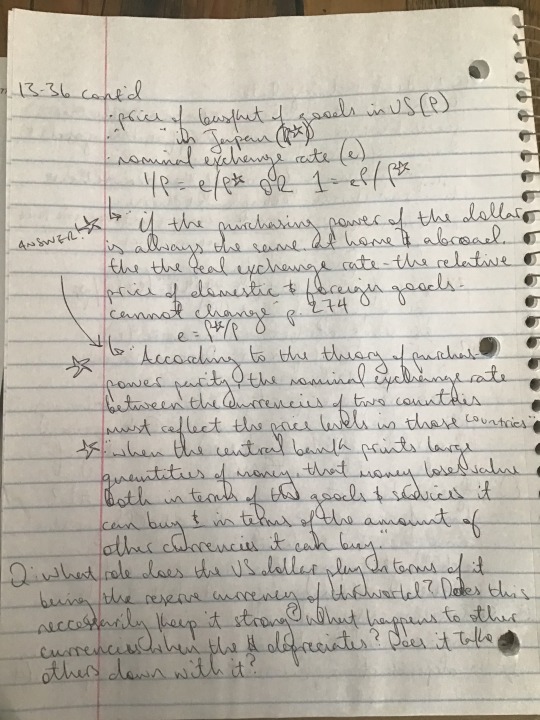

Chapter 13 Reflection/Notes

The three points I found most interesting in this chapter:-Case Study: Is the US Trade Deficit a Problem? The breakdown of the last three decades (at least, 1980-2010s) and how the US was handling itself in terms of international trade was particularly interesting. I am currently learning about how Ronald Reagan ballooned US debt under his presidency and it was great to see how our current economic state is tied in with his actions some 30+ years ago. I also found the tiny blurb at the bottom great- about how then President Donal Trump was, at the time of print, burning bridges as far as international trade (particularly with China) goes. The pie charts to the left on pg. 268 that show how economists feel about trade balances and trade negotiations was also very insightful. Particularly the pie chart that shows most economists disagree with the statement, “An important reason why many workers in Michigan and Ohio have lost jobs in recent years is because US presidential administrations over the past 30 years have not been tough enough in trade negotiations”. I feel like Trump used this misconception to win a lot of votes from disenfranchised people in the Rust Belt. He also used it as an excuse to sabotage the US’s relationship with China. -The algebraic equations used throughout the chapter were very confusing at first. After writing them down and shifting them around a bit, they began to make more sense. The ease and clarity of trusting these simple equations was helpful. I understand that this is all theoretical and I wonder where I can look to find real information being plugged into these equations? I would like more history about the discovery of these formulas. Who came up with the theory of purchasing power parity for instance?-The question that I kept asking throughout the chapter was- Who sets the exchange rates? What determines a currency’s value in relation to another? The answers finally came to me on pg. 274. It all comes back to money supply and demand and the value of the money determined by price levels in each country. The table at the very end of the chapter that illustrates how purchasing power parity is not always a perfect tool, at least in the case of Big Macs, was very handy in my understanding of this.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 12 Reflection

The costs of inflation listed in our textbook are: the shoe leather costs (wasted resources as a result of holding less money), menu costs (money spent changing prices), misallocation of resources in response to relative-price variability, money wasted over paying taxes due to inflation induced distortion of earnings, money wasted due to confusion and inconvenience, and, in cases of unpredicted inflation, arbitrary redistributions of wealth. I’m not sure which of these costs is the most important or expensive. Of course, my gut reaction is that the confusion and inconvenience is, at least, the most widely felt and talked about cost of inflation. It seems to leak into each of the costs that the text book covered (p. 247-251); distorting and confusing tax rates, confusing businesses who may misallocate resources, confusing and upsetting consumers when prices change (menu costs), and costing us all “shoe leather” when we are uncertain how to handle our money in uncertain inflationary times. As for deflation, it could lead to larger problems than could inflation that is properly managed. In the event of a deflationary spiral, the economy could suffer a contraction or, at the very best, stagflation. While a small amount of predictable deflation could be nice (who’s going to balk at lower prices?)- the “prescription for moderate deflation is called the “Friedman Rule” (p.252)- deflation is not known for behaving predictably. In a deflationary economy, what cost $1 today may well cost $.75 tomorrow so why in the world would buy anything today in a world where you can always get it cheaper tomorrow? While this sounds nice to me, an average struggling citizen living in inflationary times in an already expensive area in the country, most officials are very wary of such an economy. The Federal Reserve Bank worries about deflation because it could mean a contraction in the US economy which would hardly be patriotic or in keeping with the US’s image as “#1”. Personally, I wouldn’t mind a little bit of deflation and neither would my bank account. Although Wikipedia is not always the best source, there was an argument on the page titled (Japan’s) “Lost Decades” that there were some positive effects on the social well being of the country during its period of its economy’s stagnation. There are compelling arguments for economic “degrowth”, as well, and a push for paying more attention to a country’s GDH (Gross Domestic Happiness) than for GDP. I don’t think that shifting our main focus from consumption and production to happiness and environmental well being can be all that bad. However, I’m old enough now to know that the grass is always greener and to be careful what I wish for. Inflation is something that affects the economic choices that I make. Lucky for me, I’m already a pretty frugal person who is used to getting by with very little so not purchasing luxuries does not bother me very much. Clipping coupons, seeking out deals, and generally not spending money are all pretty familiar habits of mine. I do wonder if I shouldn’t move my meager savings into a bank account that will at least pay interest, though. I’ve never been paid more than maybe $.10 interest on any of my savings accounts, but that could be because I only have a small amount of money in the bank.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 11 Reflection

It’s hard for me to come to a conclusion about the importance of cash (the actual dollar bills in my wallet, of which there are none) to the overall money supply. It would seem erroneous to assume that physical currency has little to do with the the amount of money currently flowing around our economic system. Surely, the dollars and cents most of us have at least in a jar somewhere add up to a sizable chunk of money. Why else would it be if not to function as a “medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value” (p.211) in our economy? There’s an entire “Case Study” in our textbook on page 214 titled “Where Is All The Currency?”, though, that postulates that most of our currency is held by either foreigners or criminals. So, although currency is an important component, it is maybe less important, in the grand scheme of things, than demand deposits and the lines of credit that these make available. The Federal Reserve Bank is related to the federal government in as much as the president of the United States appoints the chair to lead the institution. It’s supposed to be a nonpolitical position and institution that’s only objectives should be to “regulate banks and ensure the health of the banking system” and “to control the…money supply” (p. 215). However, it doesn’t seem like this is always the case. The Fed should remain impartial to political influences, but back in 2019, it was widely reported that then-president Donald Trump was leaning heavily on Jerome Powell (who he was responsible for appointing to chair the Fed) to lower interest rates to encourage spending in the US:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-09-11/trump-calls-on-fed-to-cut-interest-rates-to-zero-or-less

So, even though it it supposed to act nonpolitically, the Fed is not totally free from political influence. The Federal Reserve Bank spent the first two years of the pandemic increasing the money supply to avoid a financial crisis in such fraught and uncertain times. The economic contraction that was a result of the global pandemic could have become much worse had the Fed not stepped in to provide financial assistance to households and businesses in need. The injection of funds also helped stabilize financial markets. According to the article shared with us this week from the Brookings Institute, “The Fed supplied unlimited liquidity to financial institutions so they could meet credit drawdowns and make new loans to businesses and households feeling financial strains.” But, yes, to answer the second part of this question, I think that they may have “over shot” it a bit. I am worried about current and future inflation, though I do feel confident that our Federal Reserve Bank and Treasury Department will be able to keep us out of the realm of hyperinflation. Realistically, I think that maybe it’s time to consider an overhaul of the financial system in the US instead of throwing more money at the problem as was the case in the 2008-09 financial crisis. I don’t propose to know how to accomplish this, but I’m willing to bet that it could not possibly be an easy, painless, or speedy process. The Federal Reserve Bank is at this point reining in the money supply and growth due to current levels of inflation in the system. They pumped too much money into the system in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (and, in my opinion, created a moral hazard for themselves in the wake of the last financial crisis). The tools they have at their disposal now- to suck money out of the system- are to raise interest rates and sell government bonds. The Fed could also raise the reserve requirements for banks, but I have a feeling that banks are probably already preparing themselves some nice cushions in excess reserves as we head into more financial turbulence. It’s all very interesting and unnerving!

0 notes

Text

Chapter 10 Reflection

There will always be at least some unemployment in (at least US, that’s all we’ve learned about) society due to both frictional and structural unemployment. Frictional unemployment refers to the shorter spells of unemployment that citizens will face while between jobs, searching for their next source of income, hoping it will be a good fit for them. Structural unemployment refers to the unemployment that happens as a result of there being too many workers in any given industry for the relative amount of jobs available. An example of a public policy that affects the unemployment rate would be subsidized student loans and government grants made available to students in need of finical aid in order to pursue higher education. This affects the unemployment rate by providing incentives to students to go back to college to (hopefully) receive a degree or training in an industry that will bring them greater fulfillment in their careers. Again, hopefully, this would lead to higher GDP, having a better educated, trained, and committed work force. In my opinion, such policies are positive. I think that governments should act and act responsibly in steering their citizens towards furthering their educations and (always hopeful) improving their standards of living by engaging with work that they find fulfilling. I don’t know that I could come up with what I think is the “right” amount of unemployment and, in fact, I’m a little confused by some of the numbers that I have pulled up. After just a basic Google search, I found that the “natural” rate of unemployment in the US is 4.4%, which, sure that sounds fine to me. When I searched what the current unemployment rate is in the US, the most recent figure that came back was 3.6%. It seems to me like that’s going well, then, albeit a bit dubious... If I were responsible for designing programs that would affect the unemployment rate, I think I would include incentives to work including making funds available to those who wanted to pursue higher education through colleges or trade schools. I think that providing incentives to work jobs that we both know you’re not going to enjoy but somebody’s got to do sounds fair. Providing incentives to pursue work that would make you happy, too, sounds like a win-win for everyone. I might do the opposite of what the textbook suggests in terms of raising wages in industries that no one really wants to work in, but somebody has to. I think it would be beneficial to everyone if teachers got paid more, for instance, and for other public service sector jobs- waste management, for example- to pay more and offer benefits for otherwise undesirable jobs. I think that the people who have to do the nitty-gritty labor to keep society functioning deserve more respect and compensation for their work. I don’t know if time limits are necessary if you, the government, can actually convince people that you are on their side, rooting for them to do their best and be their best. That’s a pretty far stretch, though. I guess that someone would demand that we account for the cost of such programs should unemployment rates spike (which, they invariably would if you told everyone that they should feel free to pursue a job that they could actually enjoy and/or the government was going to make it worth their while to do the jobs no one else wants to do). I guess I have some pretty pie-in-the-sky socialist dreams here that I can’t see ever realistically coming to fruition in the US. I'm not saying that everyone should be encouraged to live off of unemployment benefits and do whatever in the hell they want, but the current system doesn't seem to be working out that well, either. There's got to be a better approach to educating the work force than asking teenagers fresh out of high school to make such serious time, life, and financial committments to the rest of their lives, you know? I know so many people who are swimming in debt (and they will be for the foreseeable future) and working jobs that they resent because, right after high school, they were made to thinkn it was imperative for them to decide what in the world they wanted to do for the rest of their lives and to commit to it. I guess I'd like to normalize not going to college right out of high school and to be able to feasibly live with that decision. Yes, programs helping with unemployment should consider the type of unemployment in question. Should there be high rates of unemployment in the waste management sector due to a surplus of workers, why shouldn’t this be now considered frictional employment while these workers are being trained to work in another industry? Again, it doesn’t really make sense to me that there should be twice as many jobs as workers right now if the unemployment rate is currently below what is considered “natural” in the US. This last question confuses me. Shouldn’t the unemployment rate be higher then? I’m going to say that this does not affect my answer at all because, according to the numbers, it doesn’t seem like that dire of a situation. What is especially confusing is that, when running errands around town, I can’t help but notice all of the “Help Wanted” signs and have seen more than one restaurant close in the valley due to lack of workers. Can you help me understand this? Why do the numbers seem at absolute odds with reality?

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10443.pdf

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/3881/economics/policies-for-reducing-unemployment/

0 notes

Text

Chapter 9 Reflection

I save money because it’s important to have a little extra tucked away in case of emergencies, car repairs, moving house, and/or even the odd vacation. I don’t understand the question about why a firm would pay me something to use my “extra” money. I have never worked for a firm and have never been paid anything extra besides when working overtime (but even that’s not always a guarantee). I’ve never had enough money to invest in stocks or bonds, but I can imagine that would be a nice way to get some extra income. In future, should I have money to invest, I would balance risk and return by investing primarily in bonds rather than stocks. Money is so hard to come by that I can’t imagine wanting to take such risks with it the are required by investing in stocks. To be honest, I have not thought a lot about what I would like to do in terms of a career after graduation. Right now, I’m just trying to finish my associates degree in Sociology and I don’t think there’s a whole lot I can do with just an associates. It would probably require furthering my education with at least a bachelor’s degree to do much with. With a bachelor’s degree, I would be most interested in working as either a social worker, a community healthcare worker, or a school counselor. As far as risks go associated with the strength of the economy, I’m pretty sure that people will always needs people and that these fields will remain relatively open for new hires. The need for school counselors and social workers can only grow, in my opinion. It’s not like there are any major policies or earth shattering social movements in action to change how many people are in need of help from others. I think my educational and career choices are both pretty low risk, pretty solid in this regard- these jobs aren’t going anywhere. However, the risk involved in these choices comes in the form of relatively low salaries. According to this article from The Muse, here’s a list of potential jobs and salaries for students graduating with at least bachelor’s degrees in sociology:

https://www.themuse.com/advice/sociology-degree-major-jobs-careers

Were I to choose to get a job as a social worker, according to this article, I can expect to make an average of about $49,000/year. A quick google search, though, tells me that the average social worker in the US makes about $64,000/year, which is slightly less nerve wracking. Without a degree, though, I can tell you that I regularly made about $20,000/year so, really, anything more than that will suit me fine. According to this page on CMC’s website, in-district students living off-campus can expect to pay $20,333 for two 15 credit hour semesters. Seeing as I only have one 15 credit hour semester left, let’s halve that number for me- $10,166.50. According to the Education Data Initiative website, the average cost of one year of college at for a student classified as in-state in Colorado is $22,200:

https://educationdata.org/average-cost-of-college-by-state

So let’s add all this up: $10,166.50 (cost of finishing my associates) + $88,800 (cost of four years of college in-state CO) = $98,966 (total amount spent just on college fees to get a bachelor’s degree in sociology)

As previously mentioned, a social worker can hope for an average income of between $50-$64K a year. So, on paper, no this isn’t a great financial investment. It looks like I will need to be in debt for quite a while after graduating, especially seeing as interest rates are on the rise. Unfortunately for me, I’m not very interested in the kinds of jobs that make a lot of money- or in answer to your question- I am more interested in the non-monetary aspects of my potential career. I have never known what I want to be when I grow up besides that I wanted to help people so this comes as no surprise to me as I don’t think our society really highly values the average jobs that fall under that umbrella.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 8 Reflection

According to N. Gregory Mankiw, author of our textbook, “Brief Principals of Macroeconomics”, when the federal government is running at a deficit, or the amount of national debt exceeds the amount of revenues received, this effects the supply of loanable funds negatively. That is to say, the more indebted the country, the less money there is to lend out. I tried to find some kind of number somewhere that would give me the current total of available loanable funds within the US, but all I got was ads. Is this a readily available figure? All that I can assume, based on the last year of inflation and rising interest rates, is that maybe there were too many available loanable funds. Due to many factors (in part, ex-presidents trying to buy votes) our current inflationary economy must have been caused by too much money in the system. This is why the Fed have been steadily raising interest rates over the last year. Last March, they raised interest rates from nearly 0% to .25%-.5%. This may not seem like a huge move, but let say you just bought a million dollar house expecting to pay little to no interest on it. With an interest rate now at just .25%, you’ve incurred $250,000 in interest payments alone. Over the course of a year, your monthly payments have just increased by almost $21,000. I don’t know that many people with that much extra money to budget into each month. A year later, and interest rates are now between 4.5%-4.75%. Raising interest rates is the Fed’s number one tool to try to deflate inflation, as it sucks excess capital out of the system. In the 1980s, in order to combat a particularly stubborn bout of inflation, interest rates reached nearly 20%:

https://www.bankrate.com/banking/federal-reserve/history-of-federal-funds-rate/

Throughout my lifetime, interest rates have mostly only trended downwards. This seems to have encouraged more spending than saving, but I could be totally wrong here. It feels to me like rates are going to have to rise even further over the next year because it seems like there is still some excess capital being thrown around at speculative assets (namely, cryptocurrencies). This article came out last June, but it still haunts me today:

https://today.duke.edu/2022/06/don%E2%80%99t-expect-gas-food-or-housing-prices-drop-soon-experts-say

If we think about the supply and demand of/for loanable funds, there seems to be a higher demand than supply right now. By raising interest rates, hopefully this will also encourage both private and public saving, thereby increasing the amount of loanable funds over the next several years or decades. Although, I’m not sure how easy it will be to save money in such a highly indebted country. In 2022, the national debt was about 122% larger than the national GDP:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/269960/national-debt-in-the-us-in-relation-to-gross-domestic-product-gdp/

If we are indeed heading into a recession, during which expected return on investments will be lower, this will only encourage further saving (hopefully). If, by some unforeseen circumstance, we are heading into a time of booming economic prosperity, then return on investment will be anticipated to be greater and so lenders will be happy to lend and borrowers happy to borrow. Unfortunately, it seems like we’ve left the days of optimistic speculation behind. Again, in my life time, we have primarily experienced falling interest rates, encouraging borrowers to borrow and lenders to lend, leading to an economy that, on paper and to my eyes, doesn’t look very different from the excessive times of the 80s (shoulder pads out to HERE). In my short, bless-ed life I have seen countless high-end cupcake bistros, cookie parlors, endless apps promising to change your life, excessively content loaded streaming platforms, tech start-ups hell-bent on changing the world, kids earning six-figure incomes for posting about absolutely nothing on social media, and- the cherry on top- the rise and fall of cryptocurrency. I think we are just now seeing the train of excess pull out of the station and that we may be in for a rude awakening once the last ultra chic pet-salon-five-star-hotel-and-all-organic-doggie-restaurant close its doors for good. As for me, I will continue to not have very much money and plan on continuing to not spend it.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 7 Reflection

By providing subsidies in both higher education and healthcare, the federal government can contribute to higher productivity amongst its citizens. When the government subsidizes student loans or makes grants available to students in need of financial assistance, they are increasing the "human capital per worker". Human capital per worker is defined by Mankiw in our textbook as “the knowledge and skills that workers acquire through education, training, and experience” (p. 130). The better educated the population- that is, the longer each citizen spends in the education system and the quality maintained within that system- the more productive that population can be (in terms of GDP). Not everyone has the means to further their education after public school, though, so subsidized loans and grants are the government’s ways of making sure that more of their citizens have access to higher education. Personally, I think this is great and am very grateful for all of the financial assistance I’ve been awarded because otherwise, I would be unable to attend college. Here’s a pretty interesting break down of federal vs. state government spending on higher education and how it has changed over the past two decades: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2019/10/two-decades-of-change-in-federal-and-state-higher-education-funding This information was published in 2019 and it would be interesting to see the updated graphs that incorporate data from the last three years of a global pandemic. Reading along, I couldn’t help but wonder if government subsidies, while incredibly helpful and necessary, haven’t also been somewhat responsible for the “sky-rocketing costs of tuition” we’ve see over the last thirty or so years. If the government is willing to foot yea-much of the bill each year, what’s stopping institutions from raising costs each year to capitalize on what more student borrowers can afford? It’s seems like a little bit of a catch-22, damned if you do, damned if you don’t sort of situation. Higher education access for all those who want to partake not only increases GDP, but can that higher educated populace will go on to make safer decisions regarding health and lifestyle choices. Surely I do not have to list for you the benefits of having a healthier and more safety conscious society. Thanks to the Affordable Care Act, passed under the Obama administration in 2010, more citizens- educated or not- were granted access to health care that they would have otherwise not received. I am also a huge fan of subsidized healthcare because, without it, I would not be able to afford health insurance which would mean I could not afford access to the medication that I require to maintain a healthy life. Here’s an article that I found that explains how the government provides coverage through a subsidized healthcare network so that more Americans have more access to more healthcare providers: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/explaining-health-care-reform-questions-about-health-insurance-subsidies/ As far as infrastructure goes, the government subsidizes the maintenance and sometimes improvement of physical aspects of the country that are necessary to the functioning of the economy- road ways, bridges, waterways, ports, railroads, public transportation, etc.- by providing grants and tax breaks to companies that perform these projects. Again, I trust that I don’t need to elaborate on the importance of such improvements and investment in the county’s physical infrastructure, but I found a good article from investopedia.com that spells it out in detail: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/060215/how-do-government-subsidies-help-industry.asp How should we choose the appropriate subsidy for activities that improve productivity? In my opinion, health, education, and infrastructure are of top tier importance when choosing which activities to subsidize. How can it all be paid for? Ideally with a mass overhaul of the tax system in this country. Higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy and less tax payer money diverted to military spending. More tax payers dollars showing up in improved systems and infrastructure would be a great way to convince tax payers that higher taxes can be a good thing if we actually get to enjoy the benefits. In answer to the question regard population growth, I think more lenient policies regarding immigration would be beneficial. You state that immigration numbers are currently “well below historic levels”. I say why in the world is this the case? 99.99% of people who move to the US do so to work hard to make a better life for themselves and/or their families. Why in the ever loving world would a country- built on the backs of immigrants and slaves- deny access to or impede the process of immigration? It reminds me of a story about one of my neighbors who literally shot himself in his bigoted foot because it was of utmost importance for him to carry his revolver around on his hip so that everyone could admire how tough he was. Way to go guy(s).

0 notes

Text

Chapter 6 Reflection

The section in Chapter 6 of our textbooks brings up three majors problems with the way the CPI is calculated: it does not account for substitution bias (wherein consumers will substitute cheaper goods when the prices of some standard goods, often included in the CPI basket, rise); nor does it account for the introduction of new goods (with rapidly changing technology, it’s hard to keep on top of new goods introduced to the market that may make their way into the average consumer’s basket and possibly change consumption of other goods); and finally, it does not account for a change in the quality of goods (for example, if there’s a really bad year for apples and the quality of apples drops considerably to the point that no one is buying them as much this year, the CPI would still include the cost of apples into the consumer’s basket, even though no one is buying this year). As far as how serious these problems are, they sound to pretty glaring obviously present a problem here, as far as the accuracy of the CPI is concerned. However, I am just a simple Intro to Macroeconomics student and I cannot imagine a solution to any of these problems as it would seem impossible to keep up with all of these changing factors. Living in a very rural area, it does seem that the rate of inflation is running higher here than in urban areas. I do remember hearing a report on the local news station last Fall that gave the region deemed the “Mountain West’s” rate of inflation two percentage points higher than the country’s average. I went to the Bureau of Labor Statistics website and found in our area, the rate of inflation is currently just above 6%:

https://www.bls.gov/regions/west/news-release/consumerpriceindex_west.htm

Contrary to what I had heard or understood previously, it seems that the national average is about the same, based on the CPI-U:

https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0&output_view=pct_12mths

I can’t quite make sense of this as I would assume that prices are higher where I live based solely on my experience of living here. On average, prices are always higher in/around the Roaring Fork Valley than, say, in Phoenix, AZ, when I go to visit my family. This is a little confusing, but then again, I’m willing to accept that we all probably assume that our area- whatever area we live in- is the most expensive or at least more expensive than that area over there. I also found this interesting article from the Financial Times that explains that the Federal Reserve are not as concerned with the CPI as they are the PCE, the Personal Consumption Expenditures:

https://www.ft.com/content/87593f86-501d-4e28-ac1f-bb72127bcc7f?accessToken=zwAAAYaEnEOekdOHWT-GUB1OKNOsH7tyEnvMfw.MEYCIQDpA6HShny_X-AUED_6s5aUVXsi7HRKSe8L-NjULBB2CwIhAPfhxoODFmTUD5j4U8ZQYai_a5cIYGi3e_NfYi4mePMm&sharetype=gift&token=c9aa0d5b-799f-4860-900e-b4a42be70c51

Here’s a quote from the article by Alexandra White, Jennifer Hughes, and Kate Duguid:

The personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, which measures how much consumers are paying for goods and services, increased 0.6 per cent month on month, after rising 0.2 per cent in December. The annual rate increased to 5.4 per cent in January from an upwardly revised figure of 5.3 per cent a month earlier. The so-called core PCE index, which strips out volatile food and energy costs and is the Fed’s preferred inflation metric, rose 0.6 per cent in January, up from 0.4 per cent in December. The annual rate increased to 4.7 per cent from an upwardly revised figure of 4.6 per cent in December, missing economists’ expectations for a moderation to 4.3 per cent.

That is to say, I don’t regularly follow either of these price indexes, but thanks to this class and a partner who is really interested in markets, I am paying more attention now. It seems like all of the stated uses of the CPI and/or CPI-U are necessary, and that some users are probably more disproportionately affected by changes to either index than others. I can see how and why this tool is used, but clearly it is not perfect and I have no idea how to even begin to approach fixing it. To sum up how I am getting along with this subject matter, I’d like to end with a quote by Johnny Nash, “There are more questions than answers…”

0 notes

Text

Chapter 5 Reflection

The question that I chose to ask, based on the headings of the Chapter 5 reading, is “What other factors can economists consider that might point to citizens’ well-being?” This question is based on the heading 5-5 which already asks a pretty good question- “Is GDP a Good Measure of Economic Well-Being?” In this section of reading, it turns out while GDP is mostly a decent measure of citizens’ well-being, but it is important to acknowledge that is does not necessarily account for everything that might indicate a happy and healthy population. Mankiw makes the point that GDP does not account for environmental factors; if an economy’s government were to lift all environmental regulations on a industry, this might lead to a rise in GDP, but would not factor in the negative impacts this might have on a society (air quality, pollution, potable water, etc.) GDP also accounts for all paid for goods and services, but does not take into account volunteer work, neighbors helping each other out, or the often unpaid labor of stay-at-home parents (mostly moms). Mankiw also points out that, were all employees in a given country to stop taking days off of work, GDP would certainly rise, but quality of life would also undoubtedly fall. These are some examples of how Mankiw answers his own question in this week’s reading, but what about my question? A handy table included on pg. 101 (Table 3) lists twelve countries with the highest GDPs at the top (US, Germany, Japan) and the lowest GDPs towards the bottom (Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh). This table also lists other factors that we can consider that might point to citizens’ well-being: life expectancy, average years of schooling, and overall life satisfaction (on a scale of 1-10). There is a definite correlation between the “real GDP per person” (listed in the table) and these other factors of overall well-being. The life expectancy in countries with higher GDP is at least ten years higher than countries with the lowest GDPs which leads us to assume that the health care, life styles, and/or diets available to citizens in richer countries are better (or at least more sustaining) than poorer countries. Citizens of richer countries are also in school almost twice as long than in poorer countries leading us to believe that a better educated society is a more prosperous one. I am curious about the last column- overall life satisfaction. I’m curious as to how this data was collected, but what is shown is that people in richer countries rank themselves higher on a scale of 1-10 of how satisfied they are with their lives, at least two points higher than those in poorer countries. A current affairs example that might help answer this question would be to look at a map that tracks immigration from poorer to richer countries. Here is a link to a map that tracks immigration and immigration from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI): https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true When playing around with different settings on the map, you can see that migration is higher from poorer countries to richer countries than richer countries to poorer. Mankiw states that, “Because most people would prefer to receive higher income and enjoy high expenditure, GDP per person seems a natural measure of the economic well-being of the average individual” (pg. 100). In the US, the current GDP per person is $70,248.63 which is incredible because I can’t imagine ever making that amount of money in a year. The total real GDP of the US as of the end of 2022 (the last quarter reported on) is $20.2 trillion. In a basic Google search, it turned up that real GDP for the last quarter of 2021 was $2.25 trillion which means that it shrunk slightly. I think this matters because according to Mankiw, “…an old rule of thumb is two consecutive quarters of falling real GDP” (pg. 98) when discussing whether or not the economy is in recession. I don’t think the US has officially declared that we are in a recession yet, but it does seem possible in our economic future.

0 notes

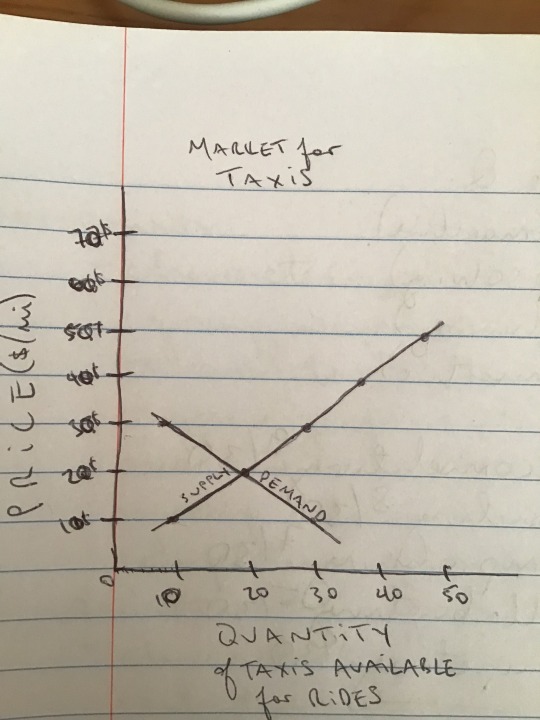

Photo

Photo #1- Here is the market for taxis (sorry, I couldn’t get the photo to flip rightside up!)

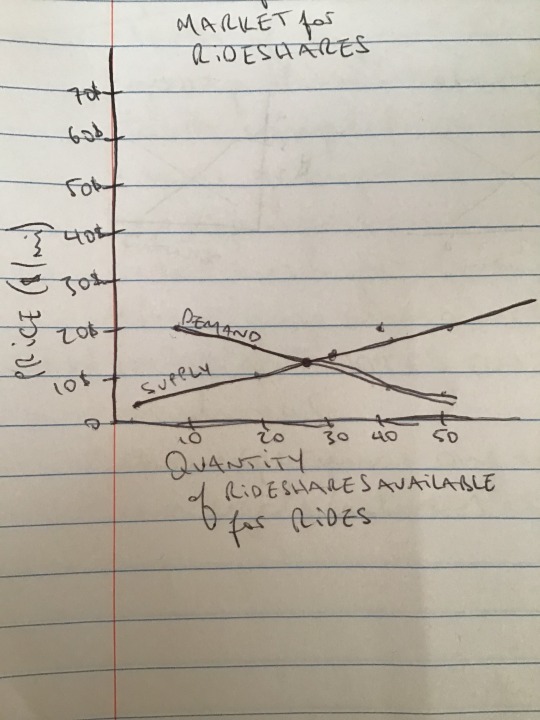

Photo #2- But wait! There’s a new app (or two) in town...

Photo #3- Here is the market for rideshares (also please excuse my crap imaginary graph skills)

Photo #4- And now, because rideshares are both more affordable and abundant...

Photo #5- The demand for taxis has fallen.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 3 Reflection

What surprised me most out of all the concepts in this chapter is simply that such complex ideas can be boiled down into the simplest of terms. It’s fascinating that in the study of economics, the models that have to be used are these hypothetical and ultra-simplified examples. It makes perfect sense why; as they explained in Chapter 1, economists can’t necessarily test out their theories in a lab. The study of Economics is being developed and refined every day and I find that incredibly interesting. At the same time, I can see how many people find it very boring- economic trends are being played out slowly, daily in a plethora of tiny factors. The model that this chapter focused on was to demonstrate absolute and comparative advantages. Again, the model was super-simplified, assuming that there are only two countries who only produce two marketable goods. And it all made perfect sense! And yet it left me wondering about the real-world implications. Does there exist some master list of countries and their viable exports? How do countries decide what to trade with whom? It seems like reading about Adam Smith or David Ricardo might be a good place to start to unravel all of this. Does our course this semester cover how and why and with whom any given country would trade? Or is that more of a political science question? I might also look into another round of Great Courses videos. I watched titled “Crashes and Crisis: Lessons from a History of Financial Disasters” by Professor Connel Fulenkamp at Duke University. It was a really interesting course, but left me with more questions than answers, I suppose. Perhaps he’s got one about trade…? I don’t think it would be wise to consider trade between the US and China and trade between the US and Wyoming as the same. In some ways they are- maybe the US is really jonesing for some disodium carbonate (Wyoming’s top export as of 2021 according to this article https://www.worldstopexports.com/wyomings-top-10-exports/) and Wyoming, in exchange, could really use some iron and steel articles (I just Google searched “Wyoming’s Top Imports” and these were number one). Trade would benefit both Wyoming and the US. The rub of it is, though, what is good for Wyoming is probably good for the US on the whole and what is good for the US on the whole is probably also pretty good for Wyoming. Wyoming is a state in the US and therefore trade within the US is just that- trade within the US, hopefully beneficial for the US. Trade with China is trade with China- a completely separate country. And what goods China has to offer for trade with the US, presumably, the US could not produce on its own. Trade with China is then even more beneficial for more people on the whole (hopefully). An item that I recently purchased that was 100% produced overseas is a tin of tea that I bought from the UK when my partner and I were over visiting his mom for the holidays. It’s a black tea that actually comes from Assam, India. There is a locally produced option, good ole’ Celestial Seasonings brand tea which is based in Boulder, CO. I consider this local because I also live in the state of Colorado. There is an even more local tea company based out of Hotchkiss, Elevation Tea. This is way more local and it would be great if I could say that I am a supporter of Elevation Tea, but the reality is, Hotchkiss is a little bit over an hour’s drive away from Carbondale (45 min) where I shop at the City Market and buy Celestial Seasonings tea on the regular. The opportunity cost and actual cost of driving to Hotchkiss just for some spanking good tea is just too high for me. But back to Celestial Seasonings vs. my Dragonfly Luxury Leaf Assam Black Tea from the Waitress in Farnham. The reason I spent money on the UK tea instead of even the Elevation Tea, is that it was a “special treat”. It was a mindless tourist purchase. Honestly, I’m wishing now that I had saved the money for some swanky Hotchkiss tea instead of swanky English tea. It’s not that great.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 2 Reflection

The Policy maker that I decided to look into for this Chapter 2 reflection is a favorite of mine, Janet Yellen. Though I don’t have to tell you, Janet Yellen is the current Secretary of the Treasury and previously served as a chair on the Federal Reserve until 2018. She also previously led the White House Council of Economic Advisors and is the first woman to have held all of these positions. It was difficult to find quotes of hers to provide examples of both positive and normative economic statements because she, unlike many of her male counterparts, is a person of few words. She reminds me of one of my favorite aphorisms- “Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to open one’s mouth and be proved one.” After some searching, I was able to obtain an article from the Financial Times that contains two whole sentences by Yellen. The first statement I would like to share could be considered an example of a normative statement. According to our textbook, Principles of Macroeconomics by N. Gregory Mankiw, a normative statement is “prescriptive…they make a claim about how the world ought to be.” (p. 26).The article in question was published on January 19th by Lauren Fedor and Colby Smith for the Financial Times titled “Treasury to Take ‘Extraordinary Measures’ as US Hits Debt Ceiling”. The statement that Yellen made to Congress- “I respectfully urge Congress to act promptly to protect the full faith and credit of the United States.” The issue that she is addressing is that the US fast approaches the limit as to how much money it has borrowed and can continue to spend before coming to terms with its current debt obligations. The statement can be considered normative per our textbook because she is making the case that the government should be acting to face this massive looming deficit. Personally, I have no idea how the US can continue to borrow and/or spend trillions of dollars with no foreseeable repayment solution. Trillions of anything is unfathomable and, besides maintaining the reserve currency of the world, I cannot imagine how or why anybody anywhere would continue to lend money to the US. Maybe everybody takes very seriously what Warren Buffet, the “Sage of Omaha”, espouses- never to bet against the US? Can a country really go on borrowing and spending in such astronomical quantities without a concrete repayment plan? I’m all for government spending because it is necessary, but if I think about the feasibility here, it’s pretty shoddy. I, as a citizen, could not expect to continue taking out loans and lines of credit that continue to exceed my ability to pay them off. If that’s the case for the feds, how can such a government expect its citizens to ever take their debt obligations seriously? The second statement from Yellen that the article provides can be considered a positive statement in an economic sense. According to Mankiw, “Positive statements are descriptive…they make a claim about how the world is” (p. 26). Fedor and Smith explain: “In order to create additional borrowing capacity, Yellen on Thursday said the Treasury would cease investments into the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund as well as the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund. Both funds will be “made whole” after a debt deal has been reached, and federal workers and retirees will be “unaffected by these actions”, she added.”

This quote contains less of a call to action by Yellen and more of a statement about the actions that the Treasury Department will be taking in order to avoid as large a catastrophe as she sees coming should Congress not get their act together. As Secretary of the Treasury, Yellen is doing what she can and surely feels a responsibility to do in her position. Hopefully these two statements are different and descriptive enough examples of both normative and positive statements in economic terms.

One claim from Table 1 in Chapter 2 of our textbook that I don’t necessarily agree with or completely understand is that “A ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.” I’m sure that I don’t fully understand how this plays out, but on the surface, I can’t help but feel that a cap on rents can only benefit those who can’t afford to pay incredibly high rent. It seems like our housing system almost punishes those who can’t afford to buy a house or property (which feels like the majority of my generation). As someone who has always rented or done work-trade for housing by my employers, I can safely say that landlords tend to charge a bit much as is. Surely, they’re just responding to demand and why in the world would they charge less for something that they can get more money out of? It’s probably been close to ten years since I was comfortable paying the rent on the place that I was living in; that is, the cost seemed to make sense for the accommodation. I feel like without a ceiling on rent rates, landlords and/or property owners would charge whatever in the hell they felt like they could and the people that could afford it would fill up their units and leave everyone else (*cough cough* service and hospitality industry workers; I’m looking at you Roaring Fork Valley) to either move farther afield, cram into sub-decent quarters, move in with mom and dad, or end up homeless. It doesn’t really seem to matter to landlords whether there is or isn’t affordable housing for everyone. Are the economists quoted agreeing here thinking that if landlords can’t charge whatever in the world they feel, landlords will cease to exist or rent out housing? I truly am confused about this one.

0 notes