Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Meditating on the Route

Tony Astarita

Nearing the end of our cross country road trip, we have managed to consume over 6,500 miles of roadway in a remarkable 10 days. Being on the road for about 10 to 15 hours every day has encouraged me to do some thinking about how people move across the country, and what the impact of the structure that supports such movement looks like.

For reasons that will be explained throughout this blog, major roadways and interstates were avoided in the directions and plans for almost all of the past Beats trips. This parameter remained the same when planning out the routes of our own trip. But it was not just tradition that encouraged us to do so. There was definitely a historical component that influenced our decision. When Jack Kerouac made his first few cross country trips in the mid to late ’40s, interstates had not yet been created. But surprisingly, our decision had less to do with historical accuracy than it did with keeping the drive interesting. The drives on interstates are usually not as interesting as smaller, more local roadways. In 1962, John Steinbeck wrote, “When we get these thruways across the whole country, as we will and must, it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.” When the Interstate Highway System was authorized in June of 1956, Steinbeck’s view seemed to express the primary criticism for the decision to implement the interstate system. In his Wired article “June 29, 1956: Ike Signs Interstate Highway Act,” Brandon Keim writes “Small towns that were bypassed by the highways withered and died. New towns flourished around exits. Fast food and motel franchises replaced small businesses.” While interstates created new infrastructure in circumventing existing towns and roadways, the interstate supporting infrastructure was a threat to pre-existing towns and communities, mostly in an economic sense. It was now possible to travel large distances without needing to venture beyond the area immediate to the major roadways. It is understandable then that as the interstate network expanded, small towns all across America continued to be pushed into dust and despair.

We came across some of these communities that, given their location relative to major roadways, were probably affected by the development of interstates. While it is difficult to find the history of these towns in the few moments spent passing through, it is not hard to imagine that some of these towns, now in a state of economic hardship, were at one point flourishing communities.

While we make it our best effort to avoid major roadways wherever possible, it is still important to recognize that it would not be possible for us to complete the same kind of mileage in a similar amount of time without the interstate system. Even though several of our experiences have elucidated some of the system’s disadvantages, there are definite advantages to the existence of interstates-- in terms of general convenience, travel times, etc-- and it is undeniable that interstates have done much to change the way that people and things move around our country, in both modernizing and developing our nation’s transport system.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, the People You’ll Meet!

Gabriella Cessna

I’ve said before that the trip is its own bubble, my classmates and Simpson and Susan have been (practically) my entire world for the past eleven days. I mean, it’s difficult to have your focus on anything but each other when you’re together for, bare minimum, 14 hours a day. As we make our trek, we must take our breaks from each other any way possible, whether it be talking to people in the streets of New Orleans or to the person ringing up our purchases at some random gas station.

My favorite instance of getting to talk to a complete stranger, to have them be apart of my inner circle for a brief time, was during our visit to Bourbon Street. Tony and I had been (more than) slightly intimidated by the mass of partygoers and drunks on the street itself, so we’d maneuvered our way to the adjacent street. We stopped at a corner, Tony intently searching Yelp for somewhere nearby that we could grab dinner, when a movie-style break up happened before our very eyes. A guy appeared in the middle of the road, attempting to hail a cab. He was closely followed by a girl, who was shouting, clearly drunk, claiming she was going to call his parents. She shoved him, screamed into his face, and he ignored her, thumb still in the air as he gazed down the street, hoping a cab would save him from this mess. Tony and I turned to each other, sharing a look and laughed silently to ourselves. At this moment, we realized there was a man standing on the corner with us, he wore American flag printed leggings, a 90’s style windbreaker, and flip flops. He watched the scene unfold right along with us. He leaned over and said “Isn’t that a mess.” before returning to his phone. Tony continued scouring Yelp, I looked for the couple (who despite being messily drunk had disappeared quickly), and the man continued texting.

Another man, who I have fondly been referring to as The Bead Man, came up and strung beads across Tony and my necks, then turned to the man and said “And some beads for Papa!” and hung beads from the man’s neck before walking away. I turned to the man and said “I guess you’re our dad now.” and he tilted his head, confused. I informed him The Bead Man had referred to him as our dad and he let out a hearty chuckle, “You two better be home by midnight!” he joked. Our newfound dad asked about how we were enjoying our Mardi Gras, and we admitted that we were a quite freaked out by the happenings on Bourbon Street. He told us not to be, and started giving some actually quite sound advice (not something I was expecting to receive from a Mardi Gras partygoer). He told us that 99% of the people we met were actually sweethearts with intimidating exteriors and that as long as we were kind and friendly, no one was going to give us any real trouble. He then asked what we were doing off of Bourbon Street and we told him that we were searching for a place to grab a bite to eat before meeting back up with our class. He asked what we wanted, and as I told him “gumbo.” he pulled out his phone and typed a number into it. I told him not to worry about it and thanked him profusely for even considering going to that much trouble for us but he waved me off and spoke to the person on the line. He asked if Ben was working, was told no, then asked if they served gumbo, was told yes, asked what time they closed, was told 10 (it was around 9:50), asked if they would be able to have a cup of gumbo ready for a couple of his friends (he turned and winked at us as he said this), was told no. He told whoever he was speaking to that he could make it worth their while if they did, but was still denied. He hung up and promised us that if Ben had been there, we would’ve gotten some gumbo. I thanked him again for going to the trouble and he, again, waved me off, saying it was no problem.

As we continued making some casual conversation with our father, he received a text and told us that he had to go meet up with some of his friends and that it was very nice meeting us. He gave me a kiss on the cheek and Tony a hug and departed.

We never learned his name, in fact Tony and I have been calling him “Dad” whenever reminiscing on our time on Bourbon Street, we never found out where he was from or what he did, but I know that the memory of this kind-hearted, absurd man is going to stick with me. We make a lot of jokes about authenticity and where it is and where it isn’t, but I know that on a street corner, talking to a drunk stranger, I found it, even if just for ten minutes.

1 note

·

View note

Text

White Sands and the Curse of Wilderness

Audrey Salmons

White Sands National Monument: the taste of the thin rind of salt that collects in low places, the perpetually rippling fingerprints in the sand. I hope that I will have the opportunity to return to this place when I have improved somewhat as an artist (though I have been reassured that constant dissatisfaction with one’s work does not go away with experience). The thought of losing such a place absolutely gutted me. In retrospect, however, White Sands is one of the places about which I should worry least. While it is not protected as a wilderness under the 1964 National Wilderness Act (due to missile overflights and possible debris from the missile range next door), as a national monument, it is relatively well-regulated; there is limited road access and removing sand from the park is prohibited.

The day after visiting White Sands, just two days after leaving the sinking wetlands of Louisiana, we drove through sand dunes in Southern California that are expanding as drought reshapes the landscape. Much of this unpreserved land has been sucked dry by industrial agriculture, and climate change is exacerbating the effects. Observing the contrast in land management led me to wonder: Why are some ecosystems preserved and others disrupted? Is this model of land management sustainable?

As far as I can tell, White Sands is allowed to exist in its current state—that is, with minimal disturbance from human activity—because it allows visitors to escape civilization and interact with a perceived wilderness, defined in the Wilderness Act of 1964 as “in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape… an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” In this relationship, human activity is understood to be necessarily harmful to wilderness, and so separation is necessary to preserve wilderness so that (certain privileged groups of) humanity may consume it in small restorative doses (such as a sunset at White Sands). This language has governed preservation of millions of acres of land in the U.S. for decades. The preservation of some land seems to somehow make up for ruining other land deemed less beautiful or intrinsically valuable. Yet this latter category of land is the one with which we are most familiar, with which we have the most direct contact. We hold at a distance the land which we seem to value most, yet have few qualms (and only an insufficient handful of environmental regulations) about tearing up the land on which we live and from which we obtain sustenance.

While driving through the national forests of the Pacific Northwest past hills of pines stripped and broken by I don’t know what, disease or fire or insects, I thought of this article about ecologist Lauren E. Oakes’s study of dead yellow cedars in Alaska (which also introduced me to the Wilderness Act as I’ve described it). As she talked to local folks invested in the cedar’s survival, a Tlingit weaver named Kasyyahgei told her: “Wilderness is a curse word.” This conversation showed Oakes that “the once well-intentioned act of protecting wild spaces had broken the relationships needed to sustain the larger whole over a much longer time frame.” This shift in perspective is necessary if we are to design a future in which our relationship with our environment is sustainable, one in which the land on which we live is respected as much as the land we make into national parks and monuments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Capture

Ashton Clatterbuck

“Capture the trip.” This was the basic class requirement for our cross country trip. Be to the van on time and capture the experiences you have or you might just miss the trip altogether. Significance of the word ‘capture’ is rather broad, left up for each person to define for themselves. I personally work best with words, so writing down every detail to every interaction I want to remember has been my method so far.

Others have opted to go the visual art route, using paint to nail down the colors of the landscape as it flashes by. In fact, the landscape changes so quickly, I will be just starting to write about green, rolling hills, look up for reference, and find that the lush, well-watered grasses have disappeared entirely, replaced by cactus plants and golden hay fields, all in the matter of minutes.

The most prominent example of the volatility of scenery was in the mountains of Montana. Up one side of the mountain, the sun would be blinding, the temperature not unbearable. Then, as though a switch had been flicked, a massive wall of snow would hit us, causing a near total whiteout, the temperature dropping several degrees. In my sketchbook, there are two pages dedicated to this weather phenomenon, walking through the event as I experienced it. If those moments of astonishment and awe had not been captured on paper, there would be no way in a million years that I would remember what my mind went through in experiencing that for the first time.

However, not every moment can be (or should be) captured in the same way I captured the fickle Montana weather. Day 5 of the trip, March 4th, I believe it was, we visited Salvation Mountain, located in Slab City. In her typical fashion, Susan, our art teacher, struck up a friendly conversation with the woman who attended the visitor table for the day. We all took interest and joined in on the conversation. At some point, a young guy about our age came up to Shannon and asked, “Hey, do you got any cigarettes on you? I’ll buy ‘em.”

”Yeah, hold on a sec.” Shannon jumped from her seat.

“How much for one? I’ve got a one. How about three for a dollar? How much will one get me?”

“I’ll give you two for it.” Shannon said, firmly as she disappeared into the front seat of a lived in van parked just behind the tent. She was only gone a moment, reemerging with two sticks in her hand. The boy handed her the dollar, thanking her profusely before jogging over to where two friends of his waited. Shannon returned her attention to our group.

“He lives up in the slabs.” Shannon said. Looking at our inquisitive faces she went a step further, explaining that a group of kids lived in the concrete ruins over the hill and liked to come down now and then to work on repairing the mountain. We continued conversation with Shannon for several more minutes. She even agreed to a recorded interview for a podcasting project we have been working on.

That entire interaction was such a special moment, I wished to freeze every detail, and study it for hours. However, I would have missed all of the nuances and expressions if attempting to simultaneously write and observe. It was only after everyone piled into the van and we were headed down the road again that my sketchbook came out and I recorded every detail I could remember.

Capturing the trip is still a challenge for me, despite there being no more than two days of driving remaining before our tired, sorry van rolls into the school parking lot. I am either trading the moment for the page or the page for the moment and the line of capturing both is either fine or dotted. Either way, I have torn through one sketchbook and the second is more than halfway filled, so I hope there is something in there worthwhile.

0 notes

Text

Authenticity

Tony Astarita One of the fundamental tensions of our trip has been deciding the best way to experience and also capture places, things, and experiences (like that of Sanderson) in a way that avoids false representation and representation that also undermines the actual thing. Frequently we exit the interstates to investigate smaller towns, towns that in many ways seem forgotten and off the map. But rarely do we leave our vehicle, in an attempt to protect whatever power and attraction that we find.

Our studies of Kerouac’s On The Road and Dharma Bums, in our preparation earlier in the year, brought to our attention some of the primary concerns and motivations of the Beat generation, namely the attention payed to the idea of “authenticity.” It is a widely accepted idea that Kerouac's search for the authentic self-motivated him to launch the journey encapsulated in On The Road, possibly the defining work of the Beat generation, and the text that has on some level served as inspiration for our own trip. To quote George Mouratidis’s “Into the Heart of Things,” the earliest Beats were motivated by an “Existential concern with ‘authentic’ being particular to the postwar period, as well as the most contemporary preoccupation with authenticity in representation.” So where “authenticity” is arguably one of the major focuses behind the Beat generation, it also makes sense to pay attention to what “authenticity” means in terms of our own experience.

Before the trip, we were-- and still are-- excited by one specific aspect of the trip: the opportunity to visit towns, neighborhoods, and other places of interest that exhibit a certain sense of the thing that we now identify as “authenticity.” That we have identified the gravitation to certain things as a function of “authenticity” is somewhat significant. But with this being the case, our approach to finding and understanding how best to experience such “authenticity” is admittedly complex. On one hand, we recognize the clumsiness that contributed to the problematic nature of the Beats’ portrayals of “authenticity.” On the other, we, like everyone experiencing some level of postmodern grief, are always in search of experiences that are real and, well, “authentic”-- in whatever form that takes. There is something about the exploration and discovery of run-down houses and abandoned buildings that is incredibly captivating, and that we cannot avoid.

In seeking for the best way to have and capture an “authentic” experience, I point towards one of the moments during the trip where we crossed through the tiny West Texas town of Sanderson on our way to Las Cruces. Sanderson was really incredible, with abandoned buildings, rusted out cars with perfect patina, dirty dogs running around the streets, etc. While we had a strong desire to hop out of our vehicle and take a million pictures, it definitely did not seem like an appropriate thing, or even the right thing, to do. However unbelievable, this was still a place where people lived, and a place where people are still making their own experiences.

1 note

·

View note

Text

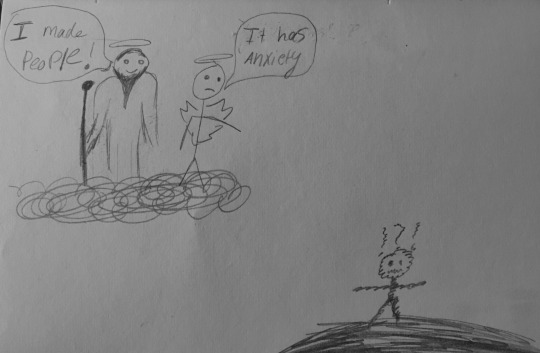

The Space Where Anxiety and Exploration Collide

Halle Richardson

Rationality is triumphed as the supreme power, but where does that leave the irrational emotions in the strictly rational world? I have constant thoughts about the worst possible outcome of a situation, while they are extremely unlikely they seem so plausible. For instance, before this trip I thought of the worst possible things would come true. I would forget something important, I would break my computer, I would regret everything second of it, everyone will hate me after spending three hours with me, ect. This builds a sense of dread inside of my head, but most of the time everything turns out fine and nothing happens. However, to prevent myself from feeling any of this tension within myself, I use humor as a defense mechanism. I think that maybe if I can just make people laugh they will like me, or if I am laughing then I do not have to open myself up to any emotion whatsoever. This becomes mentally exhausting. I am a very introverted person, so having to be social via this persona I created for nine days straight and twenty plus hours everyday, only creates more problems. I need space and at some points on the trip I struggle to find it. Some people find it fun to walk around cities for hours on end, I find it unpleasant. I prefer to go sit at a park alone and watch people, but how do I explain that this is just as enjoyable to me as walking around a pier is to someone else?

Another problem with anxiety and exploration is what happens when your worst possible fear comes true. In New Orleans, we all went to Bourbon Street (just a reminder this was the weekend before Mardi Gras). It was fine at first, but as the night dragged on more and more people started to crowd the streets. It was hard to imagine that this was the kind of place that Kerouac and Cassady actively sought out to party. I hated it. I hated the noise, trash, smell, and oh god the number of people. It was jammed packed wall to wall with hundreds of people. This was my worst nightmare. I was much more content staying on the side streets, or several streets away but my group wanted to go right through the crowd. I followed because we weren’t allowed to go off on our own, and I felt like I could no longer breathe. My hands were shaking and I kept thinking ‘oh god we are going to get trampled.’. Even after we exited the street, I still felt panicked and riddled with anxiety, I just wanted to see the van again. Again, everything worked out okay that night, but that experienced really solidified the fact that I hate big cities and crowds in general. Oh brother, do I love the small towns we stop in and the places where there is little no people. It made me appreciate every moment I have in the van and the fact that we were able to create this amazing space inside a car. Sometimes my anxiety drives me to be hyper aware of all my surroundings, so I feel like I have this itch to capture everything and if I do not I feel unsettled. In this way, having anxiety is kind of helpful. It makes me realize how special certain aspects of the trip are.

Gil Fronsdal, who is a practicing Buddhist and runs the Dharma Talks we listen to every morning, has really helped me focus on being in the present. It is hard to just think about the current moment and not the other 100 things going on in your mind, such as what is your next stop, when/if you will stop for dinner, what are people doing at home, where is your pencil, does the motel 6 soap actually do anything, etc. However, the practice of being mindful helps me center myself and notice the things around me. I often watch other people and things, but hardly ever look at myself and just observe. However, it is important to observe without judgment, so you can watch how you think and operate and just better understand yourself as a person. While using this method, I realized how much I use humor as a defense mechanism and how problematic it is. I realized self exploration was going to be apart of this trip, but never to the extent that it has happened. It is amazing what you can observe about yourself when you just take a step back and recognize the emotions you are feeling. In this rational world, it is okay to have irrational thoughts. You just have to take a step back, recognize them for what they are, and then allow them to go so you can be in the moment.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Van is a Holy Space

Gabriella Cessna

During the first week of talking about the trip, Simpson told us that the van was the trip and that the stops were fun, but not nearly as important as the van itself. I believed this instantly, but that still does not prepare someone for Van Life. The little nuances, like the separation of rows (Simpson/Gottlieb row, front seat, back seat) and how switching the seating around can make or break a day are nothing I could’ve imagined.

For the first three days, I sat in the same seat, the left in The Back Seat, and my very best friend, Tony Astarita, sat in the seat next to me for all three days. Halle also sat in the back with us for two days and it was amazing! The jokes, the cackling, the masking tape being applied to the windows isn’t something I was prepared for. We shout excitedly at cows, deer, turkeys, abandoned gas stations, houses, churches. We chant Simpson’s name until he agrees to pull over and let us walk around an area (“Ninety seconds.” He always says, we’re never there for only ninety seconds). I was very fearful that the van would be just messy and gross (which it definitely is) and that we’d all hit a point where we didn’t want to talk and were just… peeved with one another. It’s not all sunshine and rainbows, I can’t pretend like there haven’t been moments where I just couldn’t wait to get to the Motel6 and flop onto a possibly bed bug-ridden mattress and avoid everyone for as long as possible, but for the most part, I feel so lucky to be able to be my weird, loud self.

There’s been a large shift since leaving Sierra Meadows in regards to Van Life. We’ve all realized that this bubble we’ve built is going to pop and the van is now quiet, slightly anxious, and uneasy. Simpson and Gottlieb have told us many times that we can’t let the turn to start heading back East get to us too soon, that the days are still going to be beautiful and powerful and that we’ll have time to mourn the loss of our little Beat World on the last day as we head back into Lancaster, but I don’t think we’ve really taken that advice.

I look forward to the moments where I know that we’ll all be engaged and excited, like when Simpson blasts “California Gurls” or when I start reading “Undead and Unappreciated”. I know how much I’m going to miss this when it’s over so I’m trying my damndest to appreciate it while I have it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Capturing the Blue of Distance

Audrey Salmons

Though the majority of my watercolor sketches are of desert landscapes of gray, red, and ochre sand and rock, I find that I am using up my blue paints more quickly than red and yellow, as blue skies and mountains are frequently featured. As I work, I find myself reflecting often on an essay from Rebecca Solnit’s Field Guide to Getting Lost. Solnit describes the poetic physics of certain shades of blue in our world:

“The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. Water is colorless, shallow water appears to be the color of whatever lies underneath it, but deep water is full of this scattered light, the purer the water the deeper the blue. The sky is blue for the same reason, but the blue at the horizon, the blue of land that seems to be dissolving into the sky, is a deeper, dreamier, melancholy blue, the blue at the farthest reaches of the places where you see for miles, the blue of distance. This light that does not touch us, does not travel the whole distance, the light that gets lost, gives us the beauty of the world, so much of which is in the color blue.”

Solnit experiences “the blue of distance” as “the color of solitude and desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go. For the blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon, but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains.” The speed of our travel means that sometimes we have only minutes to capture a particular shade of distant blue before we lose it to increasing proximity with the object we are painting. This experience of quickly changing proximity emphasizes the principle that the painter captures the light they observe rather than the objects themselves; therefore, the image depends on the subjective perspective of the painter.

These reflections on light have also affected my assessment of the poetic catalogue of images I have collected over the course of the trip. I have noticed that in describing seen objects, the act of seeing is almost always invisible. Our mode of travel blocks out most sensory information from the world outside the van other than light, and so the images I collect on the road are largely visual. I typically record only the observed subject itself, asserting what is rather than what I experience. Records of sound are often secondary to visual information even when they are available, and smell, touch, and taste seem to demand the existence of an observer and therefore subjectivity. Since noticing this tendency, I have tried to pay attention to what information about light and perspective I can convey poetically to acknowledge the physical subjectivity of my observations.

This morning’s Dharma talk with Gil Fronsdal also reminded me of Solnit’s essay, as she connects the beauty of distant blue to the experience of desire. Echoing Fronsdal’s advice to practice being present with desire rather than constantly acting on or judging it, Solnit writes:

“We treat desire as a problem to be solved, address what desire is for and focus on that something and how to acquire it rather than on the nature and the sensation of desire, though often it is the distance between us and the object of desire that fills the space in between with the blue of longing.”

Perhaps the aesthetic value of desire that can be appreciated through mindfulness and art is some compensation for the frustration of desire. Walt Whitman seemed to believe so: “Sometimes with one I love I fill myself with rage for fear I effuse unreturn’d love, / But now I think there is no unreturn’d love, the pay is certain one way or another / (I loved a certain person ardently and my love was not return’d, / Yet out of that I have written these songs).” Perhaps it is the other way around, that we are compelled to value desire and loss because we know they are inevitable. Much of the work of the Beats follows this tendency: Kerouac’s characters never seem to find a satisfactory “IT,” and Ginsberg’s “Howl” is in part a love letter to those who lose themselves in their search.

These past few days have contained some of the most joyful, crushing, and beautiful moments of my (relatively limited) experience. As we have made “the right hand turn” and begun the eastward half of the trip, I find myself already dreading the distance that will drain the vital reds and yellows of immediacy from the experience as time passes. Layered over this anxiety is the further worry that I’ll miss out if I’m too preoccupied with the impending end. (The sensation that you are missing or unable to access or interpret something vital is in itself a sort of “blue” experience—sort of how I feel reading The Crying of Lot 49.) Perhaps I ought to take Solnit’s word for it and trust that several thousand miles and more time to process this experience may yield a different kind of beauty, which I may as well accept because it is inevitable.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Van and Art

Tony Astarita

As we rack up more and more miles every day, it has been really interesting to observe the capturing processes taking place within the van.

In the weeks leading up to the trip, there had been a lot of discussion surrounding the assembly of our personal art creation kits. This was understandably a daunting task for somebody with very limited artistic ability. My kit contained a few pencils and pens and a glue stick, all of which were wrapped up in a small eccentric pouch kindly lent to me by Gottlieb. My kit seemed especially bare when compared to the kits the other students, most of whom had decided to bring portable watercolor kits, charcoals, and colored pencils, among other tools requiring an artistic skill set that I would probably never possess.

I was worried going into the trip that my artistic abilities would inhibit my ability to capture the type of artifacts that I hoped to capture, but I have learned to embrace artforms that require a different set of artistic talents. Over the first half of the trip, blind contour drawing and collages have become my preferred capturing method. So while my artistic attempts tend to be rather reserved, the same cannot be said for the other members of the trip. It is safe to say that the other four outrank me in terms of artistic ability, and it is impressive how they’re capturing with a pretty remarkable sense of commitment and diligence. It is interesting to observe how each of us tends to do our work in our own style. We all share a couple communal resources to augment our pieces-- whether that be samples from Audrey’s personal collage kit that has been under development since Holiday Break, or from our ever growing collection of maps and visitor pamphlets.

We have recognized that the ability to capture and record quickly is really valuable, since we may only catch a glimpse of what it is that we find to be so profound and capture worthy. Blind contours, while crude and lacking detail, are useful as they make it possible to capture the very essence of something. While somewhat anecdotal, to me it has become more obvious that the quality of the art and the artifact itself is not necessarily all important. The creation process is what serves to cement something into our memories.

It is really remarkable that we are able to create not only a large volume of art but also art that is more often than not, in Gottlieb’s words, “not craft.” Besides the scissors that seem to go missing every five minutes, I am also surprised at how the group cooperates in the art creation process. It is often the case that we do whatever possible to help out our fellow Beats class members in the capturing process, whether it be for our personal journals or for the class sketchbook, a journal of collective memories from Beats trips past.

0 notes

Text

The Salton Sea

Gabriella Cessna

Warning: This blog entry contains pictures of dead fish heads.

Up until a few weeks ago, I thought the Salton Sea was called the “Salt and Sea.” From what Simpson and past Beat students had said, I knew it had once been insanely beautiful and that it had become this horrible, dying thing. I had no clue what to expect. As we arrived, Susan said, “It looks like there’s sand, but as you get closer, you realize that it’s all just crushed up fish bones.” That was my first real clue as to how absolutely heartbreaking our visit was going to be. We made jokes about being able to get out when we were ready to leave, all happy and excited after our amazing stop at Salvation Mountain.

We exited the van, Ashton ran off on his own, Simpson walked off to a little shed we’d seen on our way in, Halle gathered her paints and sat on a dilapidated cement dock with Gottlieb, Audrey searched for the perfect place to take their polaroids, and Tony and I went off to look at another little shed we’d seen and to gawk at the other old, rusted structures. We found so many dead fish heads, so many things just abandoned: an old chimney, a broken trailer, a light pole so rusted that I wasn’t even sure it was a light pole.

I left Tony in hopes of finding some solitude, hopefully something less depressing than seeing evidence of the death of the Salton Sea. I found a cool rock and sat myself down about thirty feet away from Halle on a different chunk of the old dock. I watched the sun set, amazed at the fact that despite the literal toxicity of the location, the colors were just as vivid as ever. Huge bright oranges, yellows, and blues lit up the sky as we all prepared to say goodbye. We watched the sun and the colors disappear, then Simpson said that we needed to mosey in a few minutes. No one waited even for just a few minutes, and it seemed as though everyone was pretty desperate to leave.

As we departed, the air in the van was a lot heavier than it had been. It didn’t help that break-up songs played in the background as we all sat on what we just witnessed and were apart of. No singing, no stupid frog jokes, just the inevitability of the death and disgust that goes hand in hand with a visit to the Salton Sea.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Noticing the Silence

Ashton Clatterbuck

Day 4 of the Beats road trip and oh man have we covered a lot of ground (literally and figuratively speaking). From the contented streets of TN, to the insouciant back roads of Southern Virginia, to the abandoned solitude of rural Alabama, to the tumultuous ardor of Bourbon St, New Orleans, to the refreshing reclusiveness of the Gulf, to the gut-wrenching slap oil industry expanses on TX’s eastern border, to the big skies and tiny, in every moment, there is a silent moment waiting to be caught through the power of mindfulness.

Friday, we came upon a little Alabama town that straddled a set of train tracks. A vast majority of buildings were clearly no longer in use, windows boarded, ceiling fragments laying on the barren box springs of loveless bedrooms. Empty shelving I made a very intentional point to steer clear from the rest of the group in fear of missing the experience altogether. This separation enabled me to focus on more subtle details, such as colors, and materials, but most importantly, sounds, or in some instances, the lack thereof.

The first structure I investigated was an old, two story house. It sat, raised about five feet off the ground by pillars made of stacked cinder blocks, which poked my curiosity, considering no other building was raised. Additionally, the town was not necessarily in a flood plain. Whatever the reason, I wanted badly to get into the house somehow, so, I found an open doorway in the back, took a precautionary peak, then climbed in.

Standing in a furnished kitchen, cans on the shelf and pots in the cabinet, there was something very wrong about the emptiness of the place, void of clanking pots or sizzling food, not even a TV babbling in the room adjacent. What exemplified this was the uncanny quiet of the rest of the town. Boligee consisted of many buildings, but the only one that had a person inside was the Post office, which was not an overly noisy place. Usually, while walking through the main street of a city, everyday sounds hum continuously in the backdrop, reminding you that you are not alone. Here, you were pretty much alone except for the occasional train passing through town. The persistent, singular chirp of a bird perched in a backyard tree reminded me repeatedly of just how eerily silent the town was.

This caused me to think about how we define silence, or tranquility, or quiet, and I realized that silence, in this sense, is often associated with the absence of humanity. There are really two ways to think about this. There is the absence of humanity in its entirety, meaning people who are physically present, While the other would also include all human-made structures or visible affects of human presence. The truth is, there is always sound. Even when there were no outside factors, your own body creates sound. However, the obtrusion that structures, such as this particular abandoned house, create the noise does change. Birds sign a little more nervously, deer hooves will always be distant, and cars. trains, and airplanes will always be nearby.

In the case of this house, I allowed my mind to focus on the sounds that were missing, both people, as well as the grasshopper the may have inhabited the lawn if the house were not there. This has been a learning experience for me, and I plan to continue paying attention to sound for the rest of the trip.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anything is Possible

Halle Richardson

My god. White sands. Simpson warned us it would be hard to describe White Sands, and he was right. I was sitting on a white sand dune looking out over the painted sky and realized there is no way I could ever describe this to anyone and capture what it was like or felt. It was definitely emotional, for others more so, but I did not get emotional until we were back at the van and we could see stars in the sky. It has been so long since I have seen stars that it was very powerful to see them after watching the sunset. The colors were just so vibrant. I could not help myself but think about how Whitman talked about timelessness and angels, how the sand dunes were there and will be there for all time. The colors were inspiring. The pure white, light brown, green, and red, orange, blue, yellow, purple, white, and black sky.

Dancing. Screaming. Loving. Dying. Living. Thriving.

Today I was focusing on solitude. I wanted to break away from the group, which I did and I think I was pretty successful at. I meditated with Gill Fronzdale in the morning for almost an hour, which helped frame my time at White Sands. I just wanted to find a quiet place, stare at the sky, and focus on my breathing. Even when I was there it did not feel real. While I was meditating in the sand, my mind kept going to this vision of angels. Angels in the clouds. Angels burning in the sun. Angels’ ashes making up the sand. When you are in that kind of place it is very hard not to think that the divine had something to do with the creation of that particular spot and the performance of that sunset. Even the mountains in the distance were crisp and clearly defined, but as the sun began to set they began blending in with the sand dunes in the distance.

The sky was vibrant and bright and alive, but at the same time it looked like a painting. However, no painting could ever wrapped that experience up in a pretty little bow and capture what was washed away by the sand. Being there just sparks something inside of you that makes you want to lay in the sand forever, -- just sink in and let the sand cover you like a blanket. I did not want to take my eyes off the sky for one moment, but the entire sky was alive so you had to keep looking back and forth and side to side. Then as the sun slipped behind the mountain it looked like the sky was beginning to tear open to let the color leak out, then pull it back in. some parts in the sky were so bright that it looked like it was cut and bled light.

Another moment that will stick in my mind was when I was walking back to the van with Simpson and Gottlieb. They were talking about the last time they went to White Sands on Beats and that they thought it was the last time they were going to be there. I asked Simpson if he felt that way this time and he said that he did not, and right now he felt like anything is possible.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mardi Gras

Audrey Salmons

In the days leading up to Mardi Gras, Bourbon Street rehearses the festivities with strings of beads flung from balconies lit up purple and yellow and green. We have come to watch the show and capture what we can. I take notes on my phone as we push through the crowded street until we come to an intersection held by a small battalion square holding signs clear above the chaos. Their messages are all the familiar fire and brimstone, promising destruction to those who do not worship a certain GOD. One reminds us that HOMOSEXUALITY IS SIN. I approach one sign-bearer and ask him why he’s there; my intent, I remind myself, is not to argue, which I know is pointless, but to probe for an explanation. I am not the neutral journalist I think myself to be in that moment, however, and soon he is damning me for my queerness and I am flipping him off and walking away.

“No wonder you’re on Bourbon Street!”

“Hey, you are, too, buddy!”

I am not upset. On the contrary, I feel more at ease in the crowd whose side I have taken in this bizarre and otherwise fruitless ritual. Later, I write: I’ll give you your apocalypse and you’ll give me mine.

Mardi Gras is a festival of indulgence before the long fast, and the city is swollen with tourists who have come to partake. I wonder how the significance of the holiday differs for the residents of the city, the people who clean up the beads after the party, the people whose city is sinking farther below sea level even as the oceans rise. Later in the night we pass a smiling man in a monkish white robe carrying another sign: THE END IS NEAR. Ashton turns to me and notes that he isn’t wrong.

Our drive through the bayou of southern Louisiana makes real the statistics I’d brought with me in pages from a 2007 National Geographic article, the maps of subsiding land and vanishing wetlands. We plot our path on a map showing the land that would be submerged if sea levels rose three feet, which according to the caption is “well within the realm of possibility by 2100.” The land in which we pass streets of homes and towns with raised cemeteries will be underwater along with New Orleans. When we stop the van on a road raised from water and tall reeds, I remember that the unseen birds calling are likely climate refugees. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 alone scoured over two hundred square miles of wetland, much of which provided a storm buffer to New Orleans. Such damage is compounding and potentially irreversible.

The easiest solution is to move away to higher ground. The easiest rebuttal is that people who have been forced by systemic and generational poverty to live on floodplains don’t have the means to move. The more complicated truth is that in many cases, people don’t want to move—not because they are in denial of the threat, but because they have homes, communities, belonging to the places in which they reside. New Orleans is as irreplaceable as the fragile wetlands that surround it, significant not only for its history and its contributions to American culture but also for the fact that people now call it home. A city or town arises from the interplay of human beings and geographical factors. Humans are adaptable creatures and may survive displacement as other species can by becoming generalists, abandoning the ecological niches in which they grew, but if the land on which a city is built is lost or destroyed, the city is gone, the life that was there cannot be replaced.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Up Close and Personal

Halle Richardson

We stopped a lot of places so far and I won’t describe all of them, but I will describe Boligee, Alabama. It was a dying town. There was a mayor's office, post office, surprisingly amount of traffic, active railroads, and a few broken down houses and stores. I think in a few years nothing may be left. I imagined the buildings and business where they were once bustling, but now they were broken down and flooded. It is a lot to take in when you are there and admittedly I was not very mindful of my surroundings when I first got there. I was having fun and messing around with some of the old phones and calculators in front of the house instead of taking it all in. Once I separated from the group though I felt that I was able to take in more of what this place meant, and also be respectful to our surroundings. It is very easy to miss it and it goes by in a blink, so I have been really meditating on what Gill Fronzdale means about being present and being mindful. In order to explore you need to be mindful of everything: how you are feeling, where you are, what it is, what it once be, and what can you capture. After reflecting on that stop and being mindful of those things after the fact, I started thinking about how when I look at a building that has been (presumably) abandoned I am looking at something that is dead. Gone. Forgotten. Rotting. I am able to confront death and laugh in the face of it and then drive away looking for the next death to conquer. I feel no existential dread looking at it and I can even take a cool picture to show off to my friends. “Hey, look at me I stood at death's door and walked away. Enjoy and don’t forget to like!”. I feel powerful because I can control it now. It is no longer a rotting building, it is my rotting building. I have the power to do whatever I want with it.

Nothing scares me more than this. This callous way to treat death, like I do not think twice about what I am looking at. That is when exploration is dangerous and wrong. Will I upload these pictures to this blog and other sites for the purpose of attention? Uh, hell yeah. Will I think and write about the irony, yes. However, I think I can combat some of the side effects by being more mindful of the places I am at. I do not want to be sucked into van dynamic when we stop, I want to appreciate the places and people I am seeing. I do not want to blink and miss it, especially with the places we are visiting next. If I was just mindful of how I felt and how the places were feeling, I wonder what I would have felt. What did those places want to tell me, but did not have a chance because I wasn’t open to it? I do not know, and I can't answer that question, but I do not want to have to ask that question again.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Very few more hours...

Tony Astarita

With the trip now closer than ever before, it has been an interesting process to reflect on the trip from a few different perspectives. Up until this point, I think that our collective experience has been very similar. We have all spent the last few months investing ourselves into Beat literature, attempting to hold academic conversations about our text without ever applying vague literary terms, and struggling to understand what academia actually is. I can also relate to Audrey’s granola bar shopping pre-Beat trip coping strategy. The only difference is that I’m still not packed.

In the next few hours, I believe that there will be a significant departure from the collective experience that we have become so used to, the experience that has so far shaped the trajectory of the course. As veteran Beat students can attest to, there definitely still seems to be a core group element to the trip, and so it would be wrong to suggest that the trip might lose a sense of collective achievement entirely. Even so, I predict that part of the experience will be learning to navigate the tension between individual introspective focus and the group-level experience.

For the trip to serve any function, it is clear that we need to capture not only a significant amount of evidence, but a significant amount of evidence that supports our larger claims about exploration. Something that I have spent a considerable amount of time grappling with is what exactly I want the value of my final work from the trip to be. For the most part, the other members of the class are struggling with the same thing. This trip carries a lot of weight for me: not only is this my first significant road trip, but almost 100 percent of our intended route is on territory unknown to me. Now almost 17 years into my life, spent almost entirely in the small city of Lancaster, this is the first time that I will see the United States in a very real way (albeit in a very short amount of time). But perhaps my experience is only valuable if it can be shared in a way that enables others to derive meaning. Finding exactly what serves as valuable evidence to support this agenda adds to the complexity of this task. Fortunately, at this stage in the journey, this is not something that needs to be ultra clear. It just means that we will be doing a lot of recording, a lot of writing, and a lot of art (well, the others will be doing a lot of art).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few personal reflections

Audrey Salmons

Over a year ago, before I knew I’d be taking a gap year at Stone, I made a “vision board” for my future which included a van on a scenic road cut out of a National Geographic magazine. (If I recall correctly, my younger sister had recently told me she thought I would be good at living in a van.) I thought about this project as I was flipping through dozens of magazines (most of which I have already picked over before for other projects) earlier today, gathering images which I will use in collages on the road. It occurs to me that this process may serve as a physical representation of the way in which I have been collecting the material with which I will construct my experience of the trip. I’ve done the reading; I know from the likes of Kerouac and Krakauer how I’m supposed to feel about driving across the United States, what to look for, what to record. I hope I will be able to get around the idea of the cross-country road trip enough to actually be there for it. I hope there is something new in it for me. My song lyrics have become rather repetitive lately.

---

I feel I have never been good at travel. Perhaps I do not adjust well to the sort of acceleration of experience, and so I am unable to record enough in memory or in writing to sufficiently capture what goes on around me. I’ve found that keeping a sketchbook with me is a helpful exercise, and my field notes have improved in quality over the past few months.

---

Time is passing now in the places through which we will pass. They are not movie sets, as Kerouac’s cities sometimes seemed to me, waiting for us, the protagonists, to make them come alive. The speed of travel and the limits of our perception of geography and economy and such make it easy to lose track of contiguity, to cut from stop to stop like scenes. Still, the land that connects Lancaster, Pennsylvania to San Francisco, California is where it is, mostly regardless of our imminent drive.

---

From the start of this class, I have been thinking about the places we will see that will not be where they are in their current state for much longer. National Geographic reminds me in headlines of disappearing ice, the vanishing of the Grand Canyon, the flooding of New Orleans. I do not expect to see the (already pollution-choked) Salton Sea again. I am taking these images with me alongside the apocalyptic imagery of “Howl” and other Beat texts written as Americans processed the new existential threat of the atomic bomb. I must note that this was not the first existential threat faced by Americans. Mary Annaïse Heglar notes in the context of the contemporary climate justice movement that “history is littered with targeted — but no less deadly — existential threats for specific populations… Imagine living under a calculated, meticulous system dedicated to and dependent on your oppression, being surrounded by that system’s hysterical, brainwashed guardians. Now imagine your children growing up under that system… How’s that for existential?” Rather, because the atomic bomb, and now climate change, represent existential threats to all human beings, otherwise privileged members of society (such as educated middle class white Americans, i.e. most of the Beats, i.e. myself) must grapple with these threats.

---

This morning I found myself itching to buy the right granola bars, as if such a choice will give me sufficient control over my physical conditions on the road. Well, I did not get my granola bars after all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Hours...

Ella Cessna

When Simpson first told me he believed that I would be a good fit for Beats, I had no clue what it was. I just trusted that Simpson knew what he was talking about and asked to get switched in. I’m sure you can imagine my utter glee when I found out this road trip was happening (I’m not being sarcastic, I was immediately filled with absolute wonder and joy). Now the trip is less than 11 hours away and I am completely in denial, how could this thing we’ve been talking about since October finally be happening? I’ve been trying to make the trip feel real. It sort of feels like a dream? Or one of those daydreams that you never believe is actually going to happen. As I write this, my entire being is in denial about hopping in the van and being in said van for thirteen days. I’ve intentionally tried to keep my expectations low, solely because I know it isn’t going to be peachy-keen all trip, but I couldn’t help but get so excited and hopeful about the relationships I’m (will continue) building and the experiences we’ll have. The only things I’m sure of are Motel6s (that Tony is going to be complaining about endlessly), a lot of frogs, a lot of pictures, and getting to know each other maybe too well.

I feel nothing but pure excitement. I’m so ready to go, to become better friends with everyone on the trip, to be vulnerable (I am 100% sure that I’m going to cry at least 3 times in the van), to stop in the middle of nowhere and lay in the middle of a road. This is the kind of thing that no one gets to do and that makes it so incredibly exciting and special and I can’t get over how lucky I feel to be apart of it. I was very worried for a very long time (even while trip discussions were happening), that I hadn’t made it onto the trip. I painted all seven of us as “The Beat Frogs” without believing that I’d be in the van. As much as I hear the underclassmen ragging on “spending 13 days in a van with Simpson”, I was never anything but absolutely pumped to go.

1 note

·

View note