#(and there are male and nonbinary dress historians)

Note

hi! i was reading an article on fashion history today, specifically the 1840s, and it seemed to focus heavily on the idea of clothes relating to female oppression. i was wondering your opinion, if you have the time?

the article is here, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1840-1849/

in particular, the article says “Women’s clothes became so constricting that her passivity in society was clear (C.W. Cunnington 135)”. i suppose i’m not entirely sure how valid that is? i’m just looking for another opinion, especially since i’m a complete amateur at fashion history. i know that you’ve talked before about some misconceptions around victorian womenswear, especially with corsets, so i’d love to know if this is of a similar vein to that or if it’s something different with a different background.

if you take the time to respond, thank you so much! i hope you’re doing well :)

This is. A very strange article, providing citiations for opinions as if they were facts. Like...why are you giving a citation for an interpretation of 1840s feminine clothing? I guarantee you won't find anybody in contemporary literature saying "ah yes, women dress like this because they are passive! that is the conscious reason we do this and we have all agreed on it." So it's not really a fact, is it? And therefore, why is it being cited as if it were?

They also seem very determined to believe that these clothes restricted movement to an unmanageable degree. While it's true that you can't bend at the waist easily in 1840s stays, you can still bend at the hips or kneel down. Preventing you from moving in one very specific way doesn't necessarily prevent you from accomplishing the same action with a different movement. It's also bizarre because they talk about women of limited means having access to fashion via ladies' magazines, but don't carry that through to its logical conclusion: working-class women wore similar clothing styles to their upper-class counterparts. And therefore were also wearing stays (practical applications thereof aside). And could ill afford to have their physical action limited. And therefore...? Maybe these garments weren't whalebone cages that kept women from living their lives, perhaps?

Also, this Cunnington fellow they cite for their FactPinions died in 1961. He was active primarily during the period of greatest disdain for all things Victorian- the early to mid 20th century. Are we examining those biases and comparing the opinions expressed therein to modern scholarship, World-Renowned Institution F.I.T.? No! Of course not! Why would we, when Everybody Knows Victorian women's clothing was horrible and restrictive and kept them from doing anything ever? Their society was highly misogynistic, so it must follow that every single thing about their lives was designed to actively oppress them! That's how human beings work, after all! Ahahaha! AHAHAHAHAHAHA!

[Marzi.exe has encountered an error. Please wait.]

Don't get me wrong, he was one of the founders of my main field. He and his wife saved a vast number of garments from being lost forever, and I appreciate that. But he was, as we all are, a product of his time- and that time just happened to absolutely loathe everything about the era he was examining. So I'm not sure why we're taking his word as gospel here- especially when it's not even hard fact.

Like, for example, he says that the scoop bonnets of the era acted like blinders for women, a "moral check" keeping them focused on "the straight and narrow path ahead."

Except. Mr. Cunnington.

Women can turn their heads.

You can just. You can look in another direction. You're not a horse in a head-rein when you put on a coal-scuttle bonnet, so it hardly keeps you from seeing "immoral" things. It is, quite frankly, Not That Deep.

Aaaaand there's the old bugaboo of children's corsets, with a direful comment that girls began "corset training" as young as ten years old. I've gone over this before but, whatever salacious literature of the day may imply, it was not at all common to waist-train young children. Indeed, most so-called "children's corsets" that I've encountered are more like lightly stiffened vests designed for posture support, and can't even be tightened.

There was also at least one very weird technical observation about clothing in here, which surprised me for a fashion school where you'd think at least one person editing their articles would have sewing experience: the comment that the tightly-fitted armsceyes (arm holes) of 1840s bodices kept women from raising their arms above 90 degrees.

I could be wrong, but in my experience a more fitted armsceye allows for MORE freedom of movement, not less. One of the biggest issues I've encountered- and heard other sewists complain about -with modern mass-produced garments is armsceyes cut too large. This may seem counterintuitive, but the principle is something like: Armsceye Cut Close To Armpit = Less Pulling On Body of Garment = Can Raise Arm Higher Without Disturbing Rest Of Shirt/Dress/Whatever. And for an extremely close-fitted garment like a Victorian bodice, that effect could mean that you really CAN'T raise your arm above your head. Trust me; I know this from having made the mistake too many times in my own historical sewing. Now, if the armsceyes were cut very small in general- high in the armpit but very low on the shoulder, too -that maybe could restrict movement somewhat. And I haven't examined many 1840s bodices; it's possible that's how the sloped-shoulder silhouette of the day was achieved.

But I really doubt that all women went around being unable to raise their arms above their heads given that, again, many of them had to work. And it seems weird that a fashion school would simply say "tight armsceyes Bad" without explaining themselves more specifically. Potentially, depending on what they meant, it's even downright ignorant.

In conclusion: the article is correct in a lot of specifics, like the shapes and silhouettes concerned, the trend towards historical inspiration and very subdued ornamentation, etc. It's just when they start trying to interpret the imagined Deeper Meaning of the garments, or extrapolate about the lived experience of wearing them without ever trying it/examining what women actually said about it in the period (or didn't; absence of discussion can be telling in itself) that it starts to go off the rails.

I also feel like it's emblematic of a larger issue within the field, namely: You Can Just Say Whatever The Hell You Want About Dress History And People Will Believe You. One might think academia would be immune to this and more rigorous in its fact-checking, but. One would be wrong. Probably because there have been so many myths floating around for decades, getting repeated over and over, never being questioned because- as I said above -everyone is very very ready to believe that the past was a total hellhole. And most of these myths bolster that image, so...why would anyone doubt them?

Besides the small, unimportant fact that, you know. They're not true.

I don't know. It definitely puts my professional imposter syndrome to flight, I can tell you that much.

#ask#anon#dress history#fashion history#victorian#long post#1840s#also of course there's the fact that dress history has only been a recognized field of study for. Not Long#(hint: It's Misogyny Babes)#(not that it's an entirely feminine topic or field obviously. men wear clothes too)#(and there are male and nonbinary dress historians)#(but. I don't think the fact that it's a topic traditionally associated with women can be overlooked here)#(in terms of its being brushed off and ignored by the wider historical field)

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Be a Don Cheadle not a Dave Chappelle” –Imani Gandy. Why? Because Chappelle believes one of the most marginalized groups on the planet should be made fun of. Conversely, on February 16, 2019, Don Cheadle hosted Saturday Night Live wearing a T-Shirt that read “PROTECT TRANS KIDS.”

--On This Day in History, Shit Went Down: February 16, 2019--

Don didn’t say anything, just wore the shirt for a bit. The media said lots the next day, and so did social media. Much of the commentary was positive, but much was … not, because some folks love to hate trans people. They even build an identity around it, make it a cornerstone of their “comedy” act or put silly descriptors like “gender critical” in their online bios because they imagine that what is between a person’s legs is all that matters. Fuck those bigots, and enough about recent history. Let’s look way back, because trans people have existed for as long as people have existed.

The term transgender is new, but they are not. Records from ancient Mesopotamia, going back about 5,000 years, refer to priests of the goddess Inanna called gala that may have been trans. Graves from a few thousand years ago in Northern Iraq reveal burial rites that show they considered gender to be a spectrum. Archeologists discovered different funerary artifacts for men than for women, and also different offerings for a “third gender.”

In 2011 archeologists discovered a 5,000-year-old grave near Prague of a biological male buried with the funerary rites of a female. In 5th century Lebanon an assigned female at birth masculinized their name to Marinos and joined a monastery as a child, living the rest of his life as a man, not even revealing his sex (sex, not gender) after being falsely accused of fathering a child, but rather accepting three years of exile as punishment. His sex was only revealed upon his death.

Elagabalus served as Roman Emperor under the name Antoninus from 218 to 222 and was certainly trans. Contemporary Roman historian and statesman Casius Dio referred to Elagabalus with female pronouns. Legally, Hierocles was the wife of Elagabalus, but Dio wrote that the “husband of this woman [meaning Elagabalus] was Hierocles.” Dio wrote that Elagabalus preferred to be referred to as a wife and a queen, a lady not a lord. She dressed and adorned herself as a woman of the time, and reportedly offered a fortune to any surgeon who could give her a vagina. The Sanskrit epic Mahābhārata, written in India 2,300 years ago, tells the story of a trans man named Shikhandi.

These stories are barely a sample. Across areas and eras trans and nonbinary people have lived and loved and been both accepted and maligned. The prevalence of hate is nonsensical. In 2018 Dr. Joshua Safer, Executive Director of the Center for Transgender Medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital, said, “Being transgender is not a matter of choice. It is not a fad … it is generally an overwhelming sense that their gender is not the one on their birth certificate.”

Get the book "On This Day in History Sh!t Went Down" at JamesFell.com.

Subscribe to Sweary History at JamesFell.Substack.com.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: “Queer City” by Peter Ackroyd

Thanks to @kyliebean-editing for the review request! I have a list of books I’ve read recently here that I’m considering reviewing, so let me know if you’re looking for my thoughts on a specific book and I’ll be sure to give it a go!

2.5 ⭐/5

Hey all! I’m back with another book review and this time we’re taking a dip into nonfiction with Peter Ackroyd’s Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day. Let’s dive right in.

The good: Peter Ackroyd is a hugely prolific writer and a historian clearly trained for digging through huge archives of history and his expertise shows. This particular volume--his 37th nonfiction book and 55th overall published work--provides a startlingly comprehensive timeline of London’s gay history, just as promised. Arguably, the book’s subtitle short sells the book’s content; Queer City actually rewinds the clock all the way back to the city’s origins as a Celtic town before it became Roman Londinium. From there, Ackroyd’s utilizes his extensive historical experience to trace proof of gay activity through the ages. From the high courts of medieval times to the monks of the Tudor era, the gaslit back alleys of Victorian London to the raging club scene of the 1980s--gay people have lived and even thrived in London for literal millennia, and Ackroyd has the receipts to back it up. If you need proof that homosexuality has been a staple of civilization since the Romans--and the homophobia has often recycled the same arguments for the same period of time--then look no further.

The mediocre: All that being said, Ackroyd’s “receipts” often tend towards the salacious, the scandalous, and often the explicit. It seems that legal edicts and court cases made up the foundation of his research, so us readers get to hear in full detail the punishments levied against historical queer individuals, from exile to the pillory to the gallows. Occasionally, Ackroyd dips into the written pornagraphic accounts of the time to describe salacious sexual encounters, which add little to the overarching narrative except proof that gay people do, in fact, have sex. Later down the historical record, once newspapers became more common, we also receive extensive account of the gossip pages of the day, complete with rants about the indecency of “buggery” and the moral decay of “the homosexual.” Throughout the book, ass puns and phallic wordplay run rampant, so much so that it occasionally feels like it’s only added for shock value.

While I’m not a professional historian, as a queer person I can’t help but feel that there must be more to the historical record than these beatings, back alley hookups, etc. In focus on the concrete evidence of gay activity--that is, gay sex and all the official documents surrounding the subject--it feels like Ackroyd neglects the emotional side of queerness in favor of the physical side. Even the queer poetry excerpts or diary entries of the time (which I’m nearly positive exist throughout the historical record, though once again I’m not a professional) sampled in this book are all focused on the physical act of sex. No queer person wants a pastel tinted, desexed version of our history--but we also don’t need to hear a dozen explicit accounts of gay park sex. Queer love and queer sex go hand in hand and to focus on one without the other is disingenuous, not to mention dangerous in promoting the idea that queer people are hypersexual and predatory. Admittedly, I do think the omission of queer love is an unintentional byproduct of Ackroyd’s fact-checking and editorial process. He may not have intended to leave out tenderness, but his intentional choice to focus on impersonal records--court cases, royal decrees, newspapers, etc.--rather than personal ones--diaries, poetry, art, etc.--meant that emotion was largely excluded anyway.

The bad: Though Queer City does a good job of following queer history through the ages, Ackroyd fails to connect his cited historical examples with larger sociocultural movements of the time. He discusses queer coding in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales but not the larger (oft homoromantic/homoerotic) courtly love traditions that Chaucer drew on. He describes the cult followings around boy actors playing female parts in Elizabethan and Jacobian London but neglects to put those theaters and the public reaction to them within the context of the ongoing Renaissance. Similarly, Ackroyd omits explicit connections to the Enlightenment, Romanticism, Neoclassicism, free love, and countless other cultural movements that undoubtedly shaped both the social and legal responses to the queer community. This exclusion, unlike the exclusion of queer love, had to be intentional on Ackroyd’s part; it’s hugely unlikely that a historian with his bibliography accidentally forgot to mention the last millennium’s worth of Western civilization cultural movements. It’s a massive oversight that utterly fails to place London’s queer history within the context of wider history.

And finally, last but definitely not least, oh boy does Ackroyd have some learning to do when it comes to gender, gender presentation, and gender identity. From the very first chapter, it’s apparent that Ackroyd’s research and writing focused largely on MLM cisgender men, with WLW cisgender women as a far secondary priority. While there are chapters on chapters dedicated to detangling homosexual men’s dealings, homosexual women are often pushed to the fringes of London’s queer history. They receive paragraphs, here and there, and occasionally the closing sentence of a chapter, but overall they’re clearly downgraded to a secondary priority within Ackroyd’s historical narrative. Some of this can once again be blamed on the type of records Ackroyd uses; sex between women was never criminalized or discussed in the public sphere in the same way that sex between men was, so it was a less common topic in London’s courts and newspapers. (And, once again, I have the sneaking suspicion that turning to less traditional sources would’ve helped resolve this issue, though in part the omission can likely be pinned on Ackroyd’s demonstrable preference towards male history.)

Additionally, Ackroyd tends to treat crossdressing as undeniable proof of homosexuality. While it’s true that historically queer individuals found freedom or relief in dressing as the opposite sex, the latter didn’t necessarily equal the former. Additionally, if the crossdressing individual in question was female, dressing as a man was often a way for a woman to secure more freedoms than she would receive while wearing traditional feminine outfits. (Also, he tended to use “transvestite” over “crossdressing,” and while I tend to think of the latter as more preferred, the former may be more in use among queer studies circles or British slang). Though Ackroyd briefly acknowledges that women could and may have crossdressed to more easily navigate a misogynistic world, he nevertheless continually dredges out records of crossdressing women as concrete proof of historical sapphics.

Which brings us to the elephant in the room; in clearly identifying crossdressers as homosexuals, Ackroyd entirely overlooks the existence of transgender and nonbinary people in London’s historical record. This omission, arguably unlike the others, seems definitively intentional and malicious. In the entire book, I could probably count on one hand the number of times Ackroyd mentions the concept of gender identity, and I could use even fewer fingers for the number of times he does so respectfully and thoughtfully. Though he largely neglects to discuss transgender history as a subset of queer history, when he does bring up historical non-cisgender identities it’s often as a component of his salacious narratives rather than a vibrant and storied history all on its own. In the final chapter on modern gay London, Ackroyd’s casual dismissal of the concept of myriad gender identities felt dangerously close to modern day British “gender criticism,” which is likely more familiar to queer readers as TERFism masquerading under the guise of concern for women and gay rights (JK Rowling is a very public example of a textbook gender critical Brit, if you’re wondering). By the end of the book, Ackroyd’s skepticism of so-called “nontraditional gender identities” is so glaringly evident that he might as well proclaim it outright.

The verdict: For a book supposedly focused on queerness, the focus on male cisgender homosexuality is both disappointing and honestly not surprising. This book is a portrait of gay London, yes--but it’s also a portrait of Peter Ackroyd as a historian and a professional. It’s clear from early on that he’s writing from the perspective of an older white gay man (I think queer WOC know what I’m talking about when I say that that POV is very distinct, and his clear idolation of 1960s-1980s gay culture makes his age quite evident as well). As you progress through the book, his blindspot in regards to gender and gender politics become increasingly clear, as does his simultaneous obsession and criticism with transgender identities. Overall, Queer City is a clear example of how “nonfiction” doesn’t necessarily mean unvarnished truth--or at least not all of it--and how individual historian’s methods and biases bleed into their research.

A dear London friend suggested Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London: Perils and Pleasures of the Sexual Metropolis as a more gender inclusive review of the famous city’s queer history. While I take a break from London for a bit, I would welcome any and all thoughts on either Queer City or Queer London, the latter which I fully intend to get to eventually so I can properly compare the two.

#book review#queer history#queer city#text heavy tw#sex mention tw#long post for tw#wow this got really long sorrt#kinda starts rambling by the end oops

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonbinary Genders Throughout History

I started compiling these with the intention of posting them on trans visibility day as a congrats to @neurodivergent-crow getting their top surgery consultation (woot!), but I kept finding more and more and more third gender figures and it developed into this ever-growing monster of a list of genders to research about... and next thing I know we’re entering Pride month.

I've already found 24 extinct genders and 48 modern ones, so I figured I could start with the extinct ones I’ve already researched and post more instalments as I go so people don’t have to scroll for half an hour to get to the end of this post. ;P

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ay’lonit [איילונית] (Ancient Israel)

A person who is identified as “woman” at birth but develops “man” characteristics at puberty and is infertile.

There are 80 references to this gender in the Mishna and Talmud and 40 in the classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Androgynos [אנדרוגינוס] (Ancient Israel, from at least 1st century CE to 16th century CE)

A person who has both “male” and “female” sexual characteristics.

There are 149 references to the gender in the Mishna and Talmud and a whopping 350 mentions in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Assinnu (Assyria, Mesopotamia)

An ambiguous gender often represented as being a passive man, but which also at one point was "listed among a group of female cultic attendants".

In Mesopotamia, the man was supposed to be sexually active while the woman took on the passive role. Because of the assinnu's passivity, they were categorized as a third gender figure.

-----------------------

Çengi (Ottoman Empire, now Turkey)

According to Şehvar Beşiroğlu they were “dancers who are non-moslems or [Rromani]”.

From what I understand the term has now evolved to be the feminine form of the noun “dancer” in Turkish, but it was originally considered to be a gender separate from man or woman, which is why I put it in this extinct gender list.

-----------------------

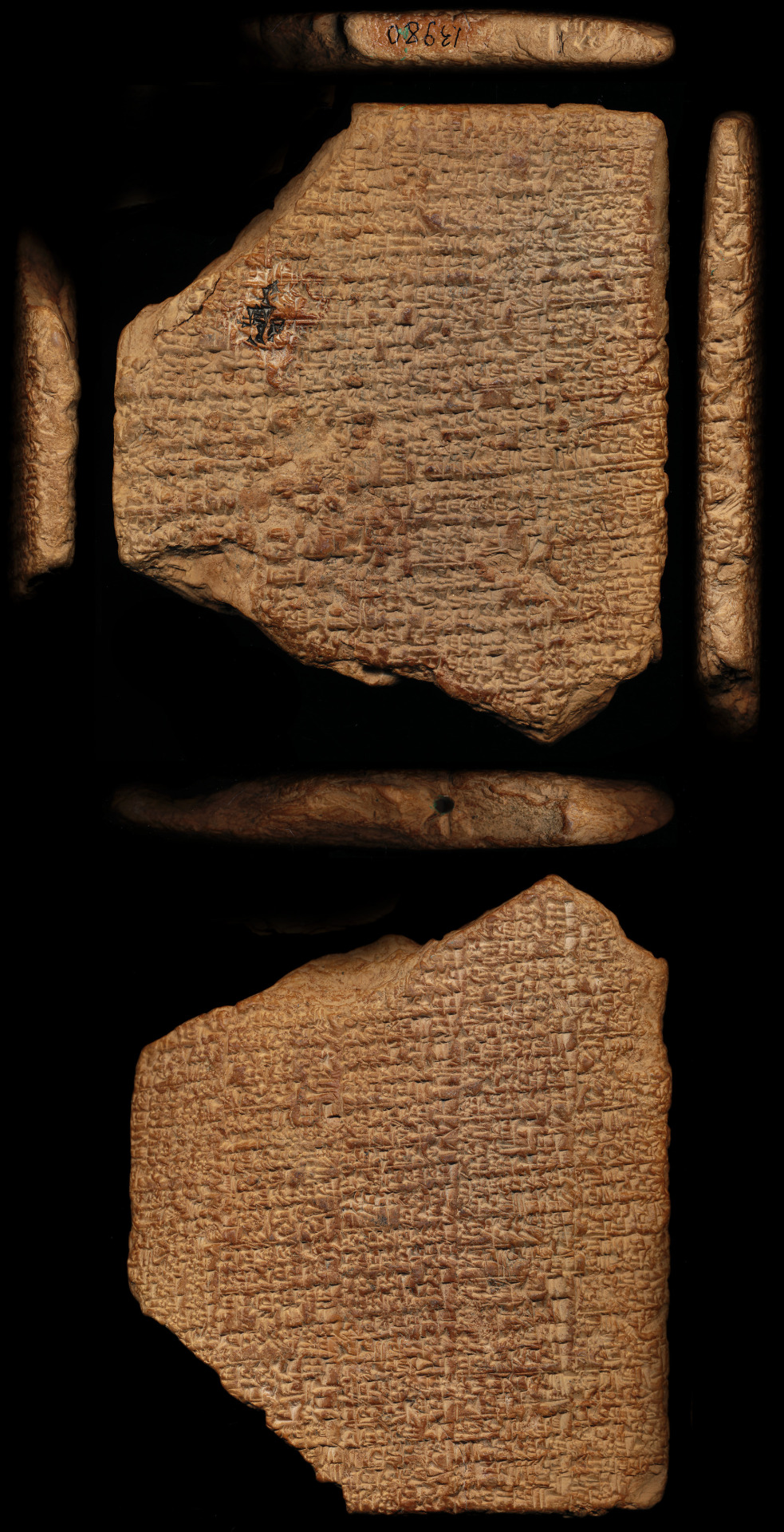

Gala (Sumer, Mesopotamia, 3000 BCE)

^ Cuneiform tablet of Old Babylonian Sumerian proverbs mentioning the gala

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a "chanter of laments".

Simply working as a professional lamenter categorized them as feminine because laments were typically performed by women (not unlike how men who practised seiðr magic were regarded in Norse culture).

During the Old Babylonian period, the role of the gala expanded and became a synonym of kalǔ, becoming a singer who dealt with music-related areas of the worship of Ishtar.

-----------------------

Girseqû (Mesopotamia)

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a childless figure within palace administration.

-----------------------

Kalǔ (Akkad, Mesopotamia)

^ According to the inscription, the beardless person is Ibni-Ištar, kalû of Ištar-of-Uruk.

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a "chanter of laments".

Simply working as a professional lamenter categorized them as feminine because laments were typically performed by women (not unlike how men who practised seiðr magic were regarded in Norse culture).

During the Old Babylonian period, the role of the gala expanded and became a synonym of kalǔ, becoming a singer who dealt with music-related areas of the worship of Ishtar.

The kalǔ were institutionalized into religious practice and ritual in order to maintain strong social distinctions between men, women, and a third gender comprised of non-conformative males.

-----------------------

Koekchuch (Itelmens, Siberia, mid 18th - early 19th century)

Individuals assigned to be men at birth but “who wear women's clothes, do women's work*, and have nothing to do with men, in whose company they feel shy and not at their ease”.

It was not uncommon for men to have up to three wives as well as one or more koekchuch (some men reportedly bypassing having any concubines altogether and preferring to have one or more koekchuch instead).

Note 1: Just as a heads up, the link for this gender has transcriptions of material from the 1750s, and as such features some racist, homophobic, and transphobic language.

It’s nothing overly colourful, mostly just the writer having the judgy kind of jerkward attitude you’d expect from a 1700s Christian ethnocentric academic, but I figured I’d give y’all a heads up just the same. :)

Note 2: The book this info comes from, Pacific Homosexualities by Stephen O. Murray, is a treasure trove for anyone interested in the subject, as it features tons of primary sources you’d be hard-pressed to find access to if it’s not your field in academia.

It costs around $40 on Canadian Amazon.

---------------------

Kurgarrǔ (Sumer, Mesopotamia)

Kurgarrǔ were people assigned as men at birth who took part of the cultic performance for Ishtar and presented themselves as militant and masculine.

The kurgarrǔ were considered a third gender because of their involvement in the worship rites for Ishtar, a role that was considered to be ambiguously gendered because Ishtar was an ambiguously gendered deity.

-----------------------

Lύ-sag/Ša rēši (Mesopotamia)

A palace attendant typically in charge of women’s quarters within a palace.

The term Lύ-sag was interchangeable with Ša rēši.

It’s implied in contemporary accounts of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods that they were eunuchs, though there are no such mentions in other periods in the culture’s history.

-----------------------

Mukhannath [مخنثون] (Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, Middle East, 4th-7th century CE)

A term used in Classical Arabic to refer to men who were perceived as effeminate.

During the Rashidun era and the first half of the Umayyad era, they were strongly associated with music and entertainment.

During the Abbasid caliphate, the word itself was used as a descriptor for men employed as dancers, musicians, or comedians.

In later eras, the term mukhannath was associated with the receptive partner in gay sexual practices, an association that has persisted into the modern day.

-----------------------

Paṇḍaka (Buddhist, 2nd century BCE)

Mentioned in the Vinaya as one of the 4 genders, it is a somewhat catch-all term for anyone who does not conform to the other 3 genders (for the other Buddhist third gender mentioned in Buddhist scripture, scroll down to “Ubhatobyanjanaka”).

“As the Vinaya tradition developed, the term paṇḍaka came to refer to a broad third sex category which encompassed intersex, male and female bodied people with physical and/or behavioural attributes that were considered inconsistent with the sexual ideal of man and woman.”

-----------------------

Pilpilû (Mesopotamia)

A member of the Ishtar cult** with feminine traits.

** When talking about ancient theology, “cult” doesn’t have quite the same meaning as it does in everyday language. It just means they worshipped Ishtar.

-----------------------

Sadhin (Gaddhi people, in the foothills of the Himalayas)

People identified as women at birth who renounce marriage and dress and work as men, but retain female names and pronouns.

-----------------------

Sanskrit Third Gender

The Mahābhāṣya, a book on Sanskrit grammar from circa 200 BCE, claims that the 3 linguistic genders of Sanskrit are based on “the three natural genders”.

The Ramayana and the Mahabharata (the two Sanskrit great epic poems) also indicate the existence of a third gender in ancient Indic society.

-----------------------

Saris [סריס:] (Ancient Israel)

A person who is identified as a “man” at birth but develops “woman” characteristics at puberty and/or is lacking a penis.

A saris can be “naturally” a saris (saris hamah), or become one through human intervention (saris adam).

There are 156 references to this gender in mishna and the Talmud and 379 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Sḫt (Egypt, 2000–1800 BCE) [pronounced “sekhet”]

“Someone who is neither a man nor a woman.”

Because the gender is known from only a few pottery shards, it’s not entirely clear whether the ancient Egyptians were referring to man and woman in the sense of sex or gender roles or both.

Note: Since the bulk of early archaeology was dominated by cishet white men who believed only two genders exist, the term has historically been generally translated as “eunuch”.

However, there’s little to no indication that sḫt were all biologically male (let alone castrated ones at that), and the eunuch interpretation of the word has begun to be questioned by gender study historians.

-----------------------

Tamil Third Gender (x2!)

The Tolkappiyam, the oldest known book of Tamil grammar, refers to intersex folk as a third "neuter" gender, as well as mentioning a feminine category of unmasculine males.

-----------------------

Tīru (Mesopotamia)

Not much is known about this gender.

Historians believe it was likely a childless castrate who had a part of palace bureaucracy (I don’t know if this is like the case of the sḫt and cishet dudes just have a propensity to assume “third gender person assigned male at birth = eunuch” or if there’s evidence to back this up).

-----------------------

Tumtum [טומטום] (Ancient Israel)

A person whose sexual characteristics are indeterminate or obscured.

According to Maimonides' Mishneh Torah, Mada, Avoda Zara, 12, 4 Tumtum is not a separate gender exactly, but rather a state of doubt about what gender a person is (kind of like a Schrödinger’s gender?).

I added it to the list because I thought that, like myself, some folks might find it interesting (and it is gender-related...). :)

-----------------------

Ubhatovyanjañaka (Buddhist, 2nd century BCE)

Mentioned in the Vinaya as one of the 4 genders, it is the gender of people with a dual sexual nature (for the other Buddhist third gender mentioned in Buddhist scripture, scroll up to “Paṇḍaka”).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S. I tried to not use transphobic language, but I’m still learning, so if anyone sees any error please let me know so I can fix it and learn from my mistake! :)

#pride month#woot woot#nonbinary#third gender#transgender#lgbt+ positivity#lgbt representation#lgbt+ history#transgender history#non-binary#happy pride 🌈#read your bible#torah#babylonia

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we are, I’ve just gotten off work from both of my jobs and it’s time to have a history lesson on the Pharaoh Hatshepsut.

While I would love to kick back, relax and read a goddamn book, thanks to that anon, I’m here to serve some knowledge on Hatshepsut with a side of fucking etemology and linguistics.

————

So transsexual (later replaced by transgender is a relatively new term coined in the 20th century in the early 1920s by one man named Magnus Hirschfeld (a physician and sexologist— and most importantly a very outspoken activist for sexuality)

Gender binaries is even a newer coined identity, the earliest record we have of nonbinary identities is 1995. So in the time of Hatshepsut the trans and nonbinary Identity wouldn’t have existed, however that doesn’t necessarily mean that gender dysphoria didn’t exist.

Now Hatshepsut is commonly referred to historians as “the queen who became a king.” Her husband/half brother died shortly after the birth of his son leaving Hatshepsut as queen regnant. It’s a fancy term for “your mommy makes all the decisions until you’re old enough.” However Hatshepsut quickly crowned herself pharaoh— which was absolutely unheard of due to the fact that during that time Egyptians believed that their gods decreed a Kings role could never be fulfilled as a women.

To which Hatshepsut told them all to fuck right off and proceeded to be one of the longest ruling pharaohs of her dynasty. The economy flourished, She was phenomenal at war and lead them into an era of peace. Oversaw so much construction and repairs. Rebuilt buildings and memorials. Generally did a lot of work for the country.

Now here is where we get into the gender discussion and inferences. The first and foremost important thing she did was change her name from Hatshepsut- which meant foremost of the noble ladies, to the male version Hatshepsu. Which means that she genuinely altered her name to assume a more manly and traditional role as a pharaoh. Now most of the time with rulers they had ceremonial garb and your normal every day garb, and while were sure she probably wore the normal sleek tight dress that female queens or regents are depicted to have worn, the importance is how she presented herself ceremonially. Hatshepsut was often depicted in a male form, with a beard, male body, and wearing the traditional king’s kilt and crown. And while it’s unsure on the logic behind it- it’s very safe to say that Hatshepsut wanted go down with a legacy that would be respected by future generations. If they depicted her as a woman she would have likely been written off as another regnant. However that’s not the case here. We recognize Hatshepsut for doing something absolutely unheard of— like altering her identity to be more kingly. Her statues while wearing traditional pharaohs clothes still potrayed her as female. However, more importantly in many statues her breasts are covered by her garb, or her arms are crossed against her chest and unseen.

Now does that mean Hatshepsut was trans? Not exactly, as trans wasn’t a coined term yet, but it’s safe to assume Hatshepsut had some nonbinary traits. We regard her as Hatshepsut, not Hatshepsu. Historians in their efforts to straightwash every important historical figures helped create her identity as a female ruler, built entirely around the heteronormative and gender binary. None of us were alive in 1437 B.C. to ask her herself what she preferred to identify as.

However we respect her for being a strong female leader that her son tried to eradicate from existence, and while there are so many questions we can ask about Hatshepsut, the Pharaoh belongs in the queer category of history because at the end of the day she defied societies gender norms in her time and ours.

So sorry anon, I’m not talking out my ass. You’re just fucking rude.

#shywrites#historically queer figures#hatshepsut#i want this to have the same energy as ‘an open letter’ from#hamilton#hatshepsu

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Debunking Enbyphobia and Panphobia

“the lgbt has become such a trend. pansexuality? nonbinary? demigender? when i was a kid, it was simple. there was lesbian, gay, bi and trans and thats it. and i’m not using any pronouns for anyone except male and female pronouns. i just find any gender neutral pronouns ridiculous. sorry. please dont force your pronouns down my throat.”

Okay there are many things wrong with this statement. Judging by your claim, you do not seem to know anything about anything outside of the LGBT acronym and that’s okay. But please do not claim to know whether these identities are “real” or “fake.” Because you only look like a fool.

Pansexuality has been a word since 1917 to denote the idea that “the sex instinct plays the primary part in all human activity, mental and physical.” Of course, it was at a time when we, as a species, did not have very much information about human psychology. While bisexuality is attraction to two or more genders (i.e. men and women, men and nonbinary, women and nonbinary, agender, genderfluid, demigender, etc) pansexual people can be attracted to all genders and/or regardless of gender.

As for nonbinary people, (and do not that bigender, agender, demigender and genderfluid is under this umbrella) while the term genderqueer came into popular use in the late 1990s, the term had it’s development in the mid 90s and implemented far earlier concepts of nonbinary identites, such as androgyny. While the terms may be new, but the concept of genderqueer is not new. For example: Kristina of Sweden. Historians know her as “the Girl King” She was assigned female at birth, but she would very often dress in men’s clothes and participate in men’s activities. She was described to have a masculine physique and was described to have a low pitched voice, similar to that of a man’s. She refused to get married and shared a bed with her lady-in-waiting, La Belle Comtesse. She reigned over Sweden in the mid 17th century.

Another example would be Hatshepsut, the female pharoah who ruled over Ancient Egypt as a man. She was in power for twenty years and was described as one of Egypt’s most prosperous rulers, profitable traders and prolific builders. But after her reign ended, her nephew Thutmose III assumed the throne and most of Hatshepsut’s inscriptions and iconography was destroyed, her name and title removed and monuments of her image vandalized. Supposedly an effort by Thutmose III to ensure the legitimacy of his son’s Ascension to the throne. She basically remained forgotten until she was discovered in the 20th century.

While it’s true that women had more rights in ancient Egypt than other civilizations, a female pharoah, at the time of her reign was mostly unheard of. At first, Hatshepsut took the unconventional method of combining male and female iconography in her statues, as many early depictions of her is shown as the body of a woman with a traditionally male headdress and dressed in an ankle length gown. In later depictions, she fully presented as a King, supposedly with a beard and muscles.

No one knows for sure the gender identity these people would’ve gone with today. One could argue that they were just very masculine women, but one can’t know for sure.

As for the misgendering thing and the “ridiculous” pronouns, referring to someone as they/them is not grammatically incorrect. People say these pronouns all the time when they are unsure of the persons gender. Example: “To each their own.”

As for the other “ridiculous” pronouns, a lot of them are derived from other languages. For example: “ze” is a Gheg Albanian dialect word, of unclear origion. But it appears in Czech and Dutch. So they’re not as far-fetched as you might think. I do understand they can be hard to say, so some nonbinary people I talk to go with they/them pronouns for auxiliary reasons.

Nobody “forces pronouns down your* throat” by asking you to use the correct pronouns when referring to them. I dont think you know what that means. Its one thing to have trouble saying the pronouns and ask for an auxiliary set but another thing entirely when you absolutely refuse to. If you willingly and knowingly use the wrong pronouns for someone, you are forcing pronouns on them. You are forcing them to be like how you expect them to and forcing them to be the gender you want them to be. Please do not act like a victim when someone gets upset at you for willingly misgendering them.

I understand that pansexuality and nonbinary identites would not make much sense to you at the moment, and that’s okay. I understand that this is your opinion. But there are facts that refute your opinion easily. I hope this makes sense. And I wish you well.

12 notes

·

View notes