#1466 - 1503

Text

Elizabeth of York, wife of King Henry VII, mother of King Henry VIII

#Elizabeth of York#Queen consort#Henry VII#House of Tudor#Wars of the Roses#Tudor dynasty#monarchy#English history#1466 - 1503

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Elizabeth of York] was only thirty-seven and still attractive when she died from complications of her final pregnancy in 1503. She had never lived in entirely tranquil times. The diplomacy in which she sometimes participated was part of Henry’s effort to establish peaceful relations with as many states as possible. Yet her death came just four years after the execution of the Yorkist pretender Perkin Warbeck and three years before the final imprisonment of the real Yorkist claimant, Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk. That she was able, devout, charitable, and kind is beyond question. That she sacrificed her claim to the throne for the good of the kingdom is obvious. That Henry used her abilities to his advantage is clear enough, but that he unfeelingly exploited her is doubtful.

— William B. Robison, The Sexualization of a “Noble and Vertuous Quene”: Elizabeth of York, 1466-1503 | The Royal Studies Journal

#elizabeth of york#henry vii#historicwomendaily#i don't think we can say she 'sacrificed her claim'#she leant into it to lend support to her husband#she would've sacrificed it if she'd refused to marry#as no englishman thought a woman could rule alone#(at that time in the 15th century)#historian: william b. robinson

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The three Elizabeth’s who marked the life of England’s most notorious king, Henry VIII — his grandmother, Elizabeth Woodville (1437–1492), his mother, Elizabeth of York (1466–1503), and his second daughter, Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533–1603).

#elizabeth woodville#elizabeth of york#queen elizabeth i of england#elizabeth tudor#elizabethan era#elizabethan england#tudor history#house of tudor#tudor dynasty#tudor england#henry tudor#henry viii#english history#british history#history#royalty#royal family#british royal family#historic#royals#medieval history#middle ages#wars of the roses#uk history#tudor era#portrait#historical painting#women history#house of york#house of lancaster

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families - Edward V of England @asoiafcanonjonsnow

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Edward V of England (1470 –1483), son of Edward IV of England and his wife Elizabeth Woodville

2) Edward IV of England (1442 – 1483), son of Richard of York and his wife Cecily Neville

3) Elizabeth Woodville (1437–1492), daughter of Richard Woodville and his wife Jacquetta of Luxemburg

4) Richard III of England (1452 - 1485), son of Richard of York and his wife Cecily Neville

5) Elizabeth of York ( 1466 – 1503), daughter of Edward IV of England and his wife Elizabeth Woodville

6) Henry VII of England (1457 – 1509), son of Edmund Tudor and his wife Margaret Beaufort

7) Catherine of York ( 1479 – 1527), daughter of Edward IV of England and his wife Elizabeth Woodville

8) Bridget of York ( 1480 –c. 1507), daughter of Edward IV of England and his wife Elizabeth Woodville

9) Cecily of York (1469 -1507), daughter of Edward IV of England and his wife Elizabeth Woodville

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#day 10#echoes from the past#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#jon snow#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#edward v of england#edward iv of england#elizabeth woodville#richard iii of england#elizabeth of york#henry vii of england#catherine of york#bridget of york#cecily of york

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

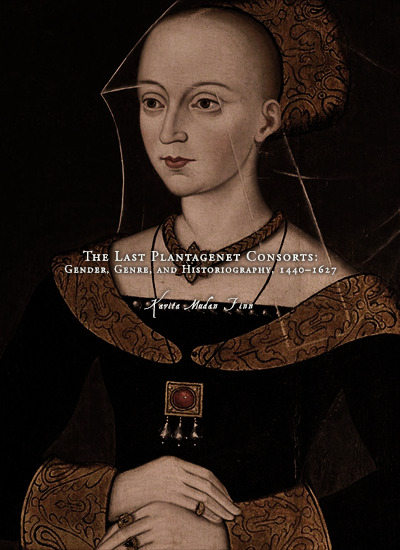

Favorite History Books || The Last Plantagenet Consorts: Gender, Genre, and Historiography, 1440–1627 by Kavita Mudan Finn ★★★★☆

Most modern accounts of fifteenth-century queens focus on separating what really happened from what was fabricated— an important distinction, particularly in such a volatile time period. What has not been considered in any detail is the fabrications themselves as narratives, and as reflections, not of fifteenth-century reality, but of the questions and anxieties that haunted their writers. Well into the Jacobean period, the civil wars of the fifteenth century—known to us now as the Wars of the Roses, through William Shakespeare’s own fabricated Temple Garden scene in the first part of Henry VI —were repeatedly invoked as the dire consequences of weak monarchy. Directly linked to these invocations, I argue, is the representation of queens, who, by virtue of their proximity to the reigning monarch and larger cultural discourses trying to make sense of that role, are inextricably associated with questions of political instability.

It can be, and frequently is, written off as a commonplace that anxiety about queens exercising political power manifests itself in historical writing—a fact pinpointed decades ago by feminist critics and therefore in no further need of exploration. My interest, however, lies in the embedded literary narratives used to illustrate that anxiety—themselves culled from multiple generic frameworks including, but not limited to, romance (in the sense of the medieval roman), hagiography, and, most prominently, de casibus tragedy—and how they echo across texts, time, and even geographical boundaries. Why do certain narratives persist and others die out? How is the choice of embedded narrative an inscription of the political and cultural climate in which the writer was working? How, especially later in the sixteenth century with the growing popularity of historical drama, does the staging of queenship deconstruct those politically and culturally motivated narratives, and, by extension, ideas of historiography and sovereignty?

There has been a recent surge of critical interest in the traumatic effects of the fifteenth-century civil wars on the English cultural psyche under the Tudor monarchs and their manifestation in texts such as A Mirror for Magistrates —to say nothing of the history plays of Shakespeare, Heywood, and that most prolific of authors, Anonymous—and it is within this dialogue of literary patterning and historiographical engagement that I wish to position this study. Most recently, in his monograph on concepts of nationhood in the two editions of Holinshed’s Chronicles, Igor Djordjevic has called for “a new critical vocabulary to refer to Shakespeare’s source-narratives,” pointing out the innate instability of the fifteenth-century historical narrative that he calls “a palimpsestic form characterized by multiple revisions, corrections, and annotations.” While I cannot claim to have produced this new critical vocabulary, an exploration of the palimpsest Djordjevic describes through the lens of how each of those layered narratives deals with questions of gender and power dynamics will hopefully open up further discussion of other ways early modern writers and readers approached and produced histories.

I focus on five royal consorts from the late fifteenth century— Margaret of Anjou (1430–1482), Cecily Neville (1415–1495), Elizabeth Woodville (c. 1437–1492), Anne Neville (1456–1485), and Elizabeth of York (1466–1503)—whose personae have been repeatedly appropriated by both historical and literary writers. By charting their changing representations in the context of larger shifts in discourses of femininity and historiography from approximately 1450 to the beginning of the Jacobean period, I propose to challenge the imposition of modern models of female agency upon this body of texts, particularly in representations of queenship, by drawing attention to generic shifts and emplotted narratives. This involves interrogating the complex relationship between literature, politics, and historiography.

My analysis of Shakespeare’s first history tetralogy, as a result, interprets these four plays in light of a century and a half of literary, political, and historiographical negotiations. Further complicating these issues is the question of the female voice: when women do display agency in these texts, it is often compromised, both in terms of generic emplotment and in terms of a more pervasive conception of womanhood that informs that emplotment. This complex relationship is highlighted in Shakespeare’s three parts of Henry VI and Richard III, all of which feature women in prominent political and rhetorical positions, but runs as an undercurrent through texts as early as the chronicles and diplomatic accounts from the mid-fifteenth century. With the advent of two queens regnant in the later sixteenth century comes a more urgent questioning of how to represent powerful women, further informed by changing historiographical trends and shifts in concepts of textual authority. The writing and rewriting of the fifteenth century led to an interrogation of historiography itself, and queens can often be found near those points of interrogation.

#litedit#historyedit#house of plantagenet#wars of the roses#english history#medieval#european history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Woodville (also spelled Wydville, Wydeville, or Widvile;[nb 1] c. 1437[1] – 8 June 1492) Elizabeth Woodville was Queen of England from her marriage to King Edward IV on 1 May 1464 until Edward was deposed on 3 October 1470, and again from Edward's resumption of the throne on 11 April 1471 until his death on 9 April 1483. Noted fact: A common knight's daughter to be the queen of England.

Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503) Elizabeth of York was Queen of England from her marriage to King Henry VII on 18 January 1486 until her death in 1503. Elizabeth married Henry after his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field, which marked the end of the Wars of the Roses. They had seven children together. Noted fact: Mother to Henry VIII and grandmother to Elizabeth I.

Elizabeth I (7 September 1533 – 24 March 1603) Elizabeth I was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Sometimes referred to as the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth was the last of the five monarchs of the House of Tudor. Noted fact: Her Era and reign were known as the Golden Age and made England prosperous and a powerful nation that defeated Spain.

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022)Elizabeth II was Queen of the United Kingdom from 6 February 1952 until her death on 8 September 2022. Her reign of 70 years and 214 days was the longest of any British monarch and the second-longest recorded of any monarch of a sovereign country. Known fact: surpassing Queen Victoria's 63-year reign.

"God save the Queens! We will remember you." quoted by 1086letsgo

#united kingdom#monarch#queens#history#elizabeth woodville#elizabeth of york#elizabeth i of england#queen elizabeth ll

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#10K2024 1-16-24

1404. Another Town, ANother Train-ABBA

1405. Disillusion-ABBA

1406. People Need Love-ABBA

1407. I Saw it in the Mirror-ABBA

1408. Nina, Pretty Ballerina-ABBA

1409. Love Isn't Easy (But It Sure is Hard Enough)-ABBA

1410. Me & Bobby & Bobby's Brother-ABBA

1411. He is Your Brother-ABBA

1412. She's My Kind of Girl-ABBA

1413. I AM Just a Girl-ABBA

1414. ROCK N ROLL BAND_ABBA

1415. Merry-Go-Round-ABBA

1416. Santa Rosa-ABBA

1417. Ring Ring (German)

1418. My Way-AVA MAX

1419. The MOTTO_AVA MAX/TIESTO

1420. Into Your Arms (feat. Ava Max)-Witt Lowry

1421. Not Your Barbie Girl-AVA MAX

1422. Sweet But PSycho (Acoustic)-AVA MAX

1423. Make Up (Feat. Ava Max)-Acoustic-VICE/Jason Derulo/AVa Max

1424. Salt (Acoustic)-AVA MAX

1425. Kings and Queens Acoustic-AVA MAX

1426. My Head and My Heart Acoustic-AVA MAX

1427. ON ME!- Ava Max, Kane Brown, Thomas Rhett

1428. Slow Dance (feat. Ava Max)-AJ Mitchell

1429. Make Up (Feat. Ava Max)-Vice/Jason Derulo/Ava Max

1430. Sad Boy- R3HAB, Jonas Blue, Ava Max, Kylie Cantrall

1431. Blood, Sweet and Tears-Ava Max

1432. My Head My Heart-AVA MAX

1433. H.E.A.V.E.N.-AVA MAX

1434. Kings and Queen-AVA MAX

1435. Naked-AVA MAX

1436. OMG WHAT'S HAPPENING_AVA MAX

1437. Tatoo-AVA MAX

1438. CALL ME TONIGHT-AVA MAX

1439. BORN TO THE NIGHT_AVA MAX

1440. Torn-AVA MAX

1441. Take You to Hell-AVA MAX

1442. Who's Laughing Now?_AVA MAX

1443. Belladonna-AVA MAX

1444. Rumors-AVA MAX

1445. So AM I-AVA MAX

1446. Salt-AVA MAX

1447. Sweet but Pyscho-Ava MAx

1448. Weapons-AVA MAX

1449,. Million Dollar Baby-AVA MAX

1450. Sleep Walker-AVA MAX

1451. Ghost-AVA MAX

1452. Maybe You're the Problem-AVA MAX

1453. Hold UP (Just Wait a Minute)-AVA MAX

1454. Diamonds and Dancefloors-AVA MAX

1455. In The Dark-AVA MAX

1456. One of Us-AVA MAX

1457. Cold As Ice-AVA MAX

1458. Dancing's Done-AVA MAX

1459. Turn off the lights-AVA MAX

1460. Get OUtta My Heart-AVA MAX

1461. Last Night on Earth-AVA MAX

1462. Clap Your Hands (Feat. AVA MAX)-Le Youth

1463. Freaking Me Out-AVA MAX

1464. ON Somebody-AVA MAX

1465. Tabu-Pablo Alboran, Ava Max

1466. Every Time I Cry-AVA MAX

1467. THE FOX (What Does the Fox Say?)-Ylvis

1468. Dragostea Din Tei---Ozone

1469. Heaven-DJ SAMMY, Yanou, Do

1470. OMG-Suki Waterhouse

1471. TO LOVE-Suki Waterhouse

1472. ...Japanese LEtters... Yoko IShida [not a sailor moon song]

1473. Intro-Neon HItch [Seasons Album]

1474. More Than Okay-Neon Hitch

1475. Head-Neon Hitch

1476. Trust Me-Neon Hitch

1477. Problem-Neon Hitch

1478. I KNow You Wannit-Neon Hitch

1479. E-Neon Hitch

1480. 1969-Neon Hitch

1481. Welcome to Try It-Neon Hitch

1482. One Step Away-Neon Hitch

1483. Worth It-Neon Hitch

1484. Like Fruit-Neon Hitch

1485. Easy to Love-Neon Hitch

1486. Ghost-Neon Hitch

1487. Bendin' Backwards-Neon Hitch

1488. Intro-Neon Hitch [Anarchy Album]

1489. Neighborhood-Neon Hitch

1490. Grade and Liquor-Neon Hitch

1491. Anarchy-Neon Hitch

1492. Why-Neon Hitch

1493. Razorblade-Neon Hitch

1494. RDLN (LINES & LUST)-Neon Hitch

1495. Dear Mr. Jesus-Amy Nieves

1496. Here We've Been-4Troops

1497. Cuando Un Nino Nacio-Amy Nieves

1498. World Burn-Renee Rapp/Cast of Mean Girls

1499. Baby Baby-Amy Grant... with Jr. Asparagus

1500. Fried Chicken at Night-Neon Hitch

1501. Boom-Neon Hitch

1502. No. 1 Lady-Neon Hitch

1503. Let Dem Go-Neon Hitch

1504. Fire Tiger-Neon Hitch

1505. Please-Neon Hitch

1506. Freedom-Neon Hitch

1507. Saturday-Rebecca Black, Dave Days

1508. Aura-Lady Gaga

1509. Venus-Lady Gaga

1510. G.U.Y.-Lady Gaga

1511. Sexxx Dreams-Lady Gaga

1512. Jewels N Drugs-Lady Gaga, T.I. Too Short, Twista

1513. MANiCURE-Lady Gaga

1514. ARTPOP_Lady Gaga

1515. Swine-Lady Gaga

1516. Donatella-Lady Gaga

1517. Fashion-Lady Gaga

1518. Mary Jane Holland-Lady Gaga

1519. Dope-Lady Gaga

1520. Applause-Lady Gaga

1521. Gypsy-Lady Gaga

1522. Eagle-ABBA

1523. Take a Chance on Me-ABBA

1524. ONE MAN, ONE WOMAN_ABBA

1525. The Name of the Game-ABBA

1526. Move On-ABBA

1527. Hole in Your Soul-ABBA

1528. Thank You For the Music-ABBA

1529. I Wonder(Departure)_ABBA

1530. I'm a Marionette-ABBA

1531. Thank You the Music (Doris Day Mix)-ABBA

0 notes

Photo

#OTD in #Tudor history, 11 February 1466, the matriarch of the Tudor dynasty, Elizabeth of York, was born. She died exactly 37 years later on 11 February 1503. Elizabeth of York married Henry VII in 1486 and was the mother of Prince Arthur, Henry VIII, Margaret Queen of Scotland and Mary Dowager Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk. She died in the Tower of London as a result of childbirth. Her newborn daughter, Katherine, also died within days of birth. Every monarch since Henry VII is a descendent of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII. 📸 National Portrait Gallery NPG 311 #elizabethofyork #onthisday #tudors #henryvii #birth #death #anniversary #historygirls #11february #february https://www.instagram.com/p/Coh63PsIk-5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#otd#tudor#elizabethofyork#onthisday#tudors#henryvii#birth#death#anniversary#historygirls#11february#february

0 notes

Text

WCW: Elizabeth of York

As you may have noticed, I’ve been periodically going through and adding WCW’s on the various English queens that I skipped-for-being-too-big in my series. Last time was Anne Neville, now it’s her successor, Elizabeth of York (1466-1503). She was the eldest daughter of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, and married King Henry VII, thus bringing... Read more →

from Frock Flicks https://ift.tt/Tx8JFNH

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

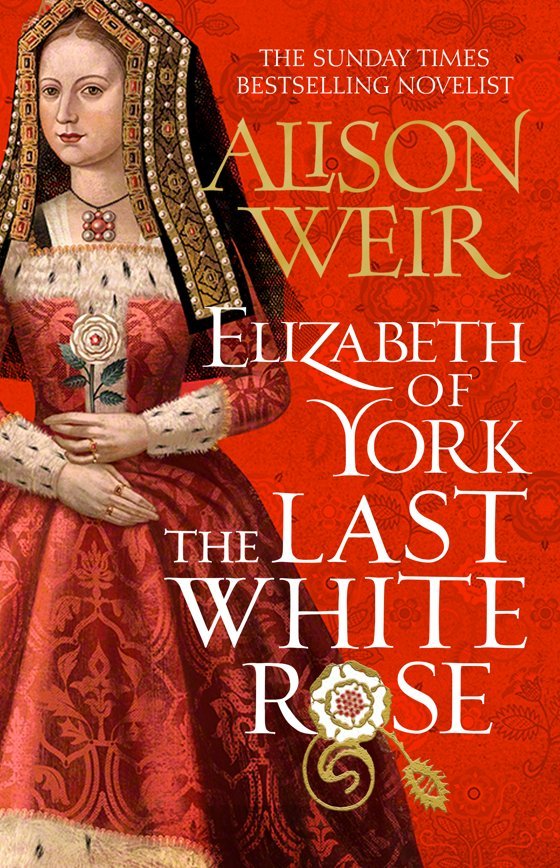

Elizabeth of York (1466-1503). Queen Consort of King Henry VII of England, whom she married in 1486, and was the mother of King Henry VIII.

On the right this is an original work by unknown author 15th century. Elizabeth keeps a white York's rose.

On the left this is a fake )) It's a modern work for a book cover. Elizabeth keeps a red carnation: the flower connected with betrothal and marriage.

#dianthus#carnation#portrait#15th century#ancient#elizabeth of york#find the difference#15th century painting#queen portrait#queen consort#women portrait#book cover

1 note

·

View note

Photo

E L I Z A B E T H O F Y O R K || Born February 11, 1466 and Died February 11, 1503

“Impeccably connected, beautiful, ceremonious, fruitful, devout, compassionate, generous, and kind, Elizabeth fulfilled every expectation of her contemporaries. Her goodness shines forth in the sources, and it is not surprising that she was greatly loved. She had overcome severe tragedies and setbacks, and emerged triumphant. We have seen how it is possible to reconcile her much debated actions before her marriage with the gentle queen who emerges after it. Certainly the sources show that, as Queen, she played a greater political role than that with which most historians have credited her, and that she was active within her traditional areas of influence. It is also clear that, far from being in subjection to Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort, she enjoyed a generally happy relationship with both of them.” – Alison Weir, Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World

#elizabeth of york#the white queen#the spanish princess#twqedit#tspedit#historyedit#tvedit#perioddramaedit#ladiesofcinema#userstream#dailyfilmtvgifs#onlyperioddramas#maries

961 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Being a damsel was a specific job. It meant that you were a lady in waiting in a house that was not your own. A lot of the time the period of service would kick in around about thirteen when families had educated their daughters to a level that was deemed sufficient. The next step of their education was to get refined and ladified, so they would get shipped to live with another, usually richer and more powerful, family.

Damsels did all sorts of work. They embroidered and helped with cloth production. They made their lady’s bed. They took messages to other rich people if their mistresses didn’t feel like going themselves. In general, they made themselves useful in whatever way was best. In return, they learned how great houses were run, made contacts among the aristocracy, and hopefully made a good impression so that they could secure a marriage with a nice (rich) young man as well.

Anyway the thing about being a damsel, as my patron Max (shout out!) pointed out, is that the main sort of work you did was essentially being an inverse influencer.

This is because the major thing that damsels did was be very conspicuously pretty, well dressed, and hanging out with the woman that they were serving, especially in ceremonial circumstances. Phillips notes, for example, that Dame Katherine Grey and Mistress Ditton served at Elizabeth of York’s (1466-1503) coronation in 1487 by going “under the table where they sat on either side of the Queen’s feet all the dinner time.” Similarly, the Countesses of Oxford and Rivers “kneeled on either side of the Queen, and at certain times held a kerchief before her Grace”.[2]

Now this is an extremely specific (and weird) flex. What Elizabeth was showing was that she was surrounded by hot important chicks at all times. She had so many hot important chicks around her that they just hung out to pass her a napkin when she needed it. Hell, she had hot important chicks sitting under the table where you can’t even see them just because she can. It’s like a late medieval version of a selfie full of Instagram baddies and a caption that says, “Quiet Tuesday in with these idiots, yawn.”

The point of having a bunch of damsels around you was to create a spectacle which highlighted the woman in charge. She looks very feminine and very powerful because she has lots of feminine powerful women surrounding her and serving her. In return, the damsels get to be a part of the spectacle and prove that they are well connected and feminine enough to be used in this manner. It’s a form of display and you, peasant, are meant to be very very impressed by it. So basically, a powerful lady or queen with a large retinue is running a hype house. I will not be apologizing for this analogy, thanks.

This is interesting though, because it acts in a sort of reverse way from how influencers work now. Influencers are, of course, expected to be extremely hot, and usually conspicuously feminine when they are women. When we have to deal with every white girl in the world in a pair of suede boots at a pumpkin patch every autumn they are acting out a specific form of girly-girlness that we are meant to recognise, respect, and respond to.

However, unlike damsels which are meant to make it clear that someone is very important, and indeed much more important than their audience, influencers have to make their audiences feel as though they are actually friends. Yes, they are standing in a million-dollar beach house in a three-hundred-dollar bikini, but maybe you could be there too with them! The only thing preventing you from doing so is buying X product which will make you just like them.

…So the difference is that influencers are attempting to create what we in the analysing society game refer to as “parasocial relationships”. That’s a technical way of saying when you feel like you have a relationship with someone based off of their media output. So, you know like how you feel that you are friends with the people who are on your favourite podcast? That is a parasocial relationship and that is what influencers do. This is in stark contrast with damsels and ladies’ courts who are extremely on a Mean Girls vibe and doing “on Wednesdays we wear pink” in front of an audience who knows that they, decisively, cannot sit with them.

Hilariously in both the medieval and modern contexts, whether the women in question are letting you know you are not friends, are trying to make you think that you are, the pretty ladies doing the display make some people very very sad. Phillips notes that in the fourteenth-century Book of Vices and Virtues it was written that damsels wearing pretty clothes were in mortal danger of their souls, both because they were vain and because they inspired lechery in the dudes who saw them. It reads:

“To behold these ladies and these maidens and damsels arrayed and appareled, that often [time] apparel them more quaintly and gaily for to make [foolish] lookers to look on them and [think] not to do great sin … But certainly they sin well grievously, for they make and be the cause of loss of many souls, and where-through many men are dead and fall into great sin; for men say in old proverbs, ‘Ladies of rich and gay apparel are arrow blast [against] the tower.’ For she has no member on her body that is not a [snare] of the devil, as Solomon says, wherefore they must yield accounts at the day of doom of all the souls that by reason of them are damned.”[3]

In other words, the damsels at court might think there is nothing wrong with being conspicuously hot in public, but in fact, it is very sinful because it creates a sinful society and encourages lust in men. TL/DR: dressing up in public means that you are in league with the devil.

…This is important to note because both medieval European society and our society now have a clearly very fraught relationship with women displaying themselves in public. The attempt to control gaze both then and now has some very visceral reactions. It can make people feel awe, or build entire relationships in their mind. It can also enrage people to the point that they condemn these women even though, and this is crucial, in neither case were they actually in a relationship with their audiences.

The important thing to take away from all of this is that women being put on display, and using that to wield power, is a very old practice. What has changed over time is the way that display is focused. Medieval people used it to keep others as an outgroup, and people now use it to make outsiders feel as though they are in. Overall, the goal is the same: accruing power, prestige, and respect to the woman who is in control of her image. This often results in backlash but the thing about it is that the world has yet to end because a bunch of hot chicks hung out one time and then someone felt bad about themselves.

Do I think that either iteration of hyper-feminine display is necessarily laudable? Not especially. I am just saying it is a constant feature in our society, and if you want to get rid of it, then we need to rethink our approach to femininity more generally. Until we can offer women more ways to gain prestige, we are gonna keep going back to old reliable: being conventionally attractive. I find it hard to get mad about that.

- Dr. Eleanor Janega, “On damsels and influencers.”

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daughters of Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV:

• Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503), Queen consort of England as the wife of Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509). Mother of Henry VIII (reigned 1509–1547).

• Mary of York (11 August 1467 – 23 May 1482), buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

• Cecily of York (20 March 1469 – 24 August 1507), Viscountess Welles

• Margaret of York (10 April 1472 – 11 December 1472), buried in Westminster Abbey

• Anne of York (2 November 1475 – 23 November 1511), Lady Howard

• Catherine of York (14 August 1479 – 15 November 1527), Countess of Devon

• Bridget of York (10 November 1480 – 1507), nun at Dartford Priory, Kent

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#plantagenet#house of york#elizabeth woodville#edward iv#graphic#elizabeth of york#cecily of york#york princesses#mary of york#anne of york#bridget of york#catherine of york#british history#15th century#war of the roses#edward x elizabeth#holliday grainger#maria valverde#elle fanning#anastasia tsilimpiou#gabriella wilde#historical#women in history#lily james#margaret of york#the white queen

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

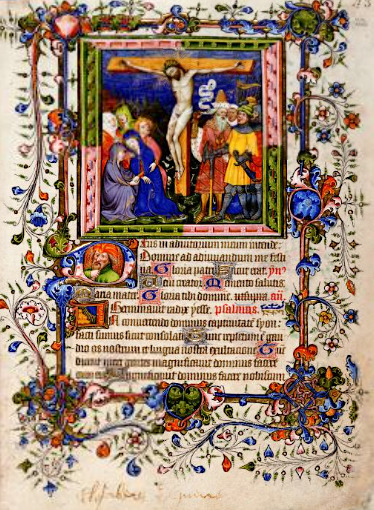

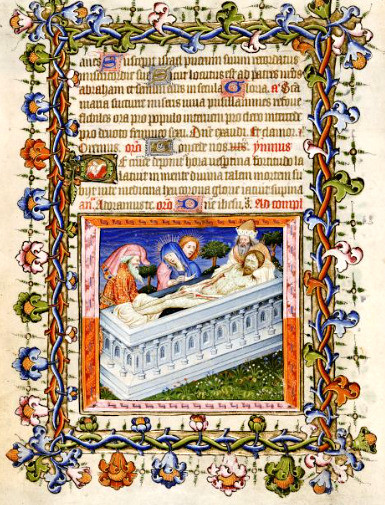

Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary — The Hours of Elizabeth of York (‘Elyzabeth ye quene’) (c. 1415)

This series from The Hours of Elyzabeth ye Quene (Add MS 50001, ff 7r-26v) depicts eight illuminated miniatures in colours and gold at the beginning of each canonical hour: The Last Supper (Matins), The Agony in the Garden (Lauds), The Betrayal (Prime), Christ before Pilate (Terce), Christ carrying the Cross (Sexte), The Crucifixion (None), The Deposition (Vespers), and The Entombment (Compline). Elizabeth of York’s faint inscription, ‘Elyzabeth ye quene’, can be seen just below the sixth miniature, The Crucifixion.

This Book of Hours is said to have first belonged to Cecily Neville, Duchess of Warwick (c. 1425 – 1450), the niece of Elizabeth of York’s paternal grandmother Cecily Neville, Duchess of York (1415 – 1495). The Hours then passed to Elizabeth of York (1466 – 1503), and later to Mary, Queen of Scots (1542 – 1587), who allegedly gave the book to one of her attendants on the eve of her execution.

Source: British Library

239 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elizabeth of York, sister of the princes in the tower and Queen of England (February 11, 1466 – February 11, 1503)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen consorts of England and Britain | [33/50] | Elizabeth of York

Elizabeth was Queen consort of England from 1486 until 1503 as the wife of Henry VII. She was born on 11 February 1466 as the daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. At age 3 she was briefly betrothed to George Neville. After he rebelled against Elizabeth’s father, the betrothal was broken off. In 1475, Elizabeth was then betrothed to Charles of France who would become King Charles VIII. The engagement lasted seven years, until Louis XI (Charles’ father) broke it off. On 9 April 1483, Elizabeth’s father died. Her younger brother briefly ascended to the throne until her uncle, Richard, took over and became King himself. Richard had Elizabeth and her siblings declared illegitimate and she, along with her mother and siblings, took refuge in Westminster Abbey. After this, Elizabeth’s mother began to conspire with Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth was betrothed to Henry Tudor. After the death of Anne Neville in 1485, there were rumors that Elizabeth would marry her uncle, Richard, however these rumors were false and a marriage between them never came to pass. On 22 August 1485, King Richard was defeated in battle by Henry Tudor, making him King Henry VII. Henry decided to take Elizabeth as his wife and the two were married on 18 January 1486. Elizabeth got pregnant shortly afterwards and gave birth, slightly prematurely, to her first child on 20 September—a boy named Arthur. Elizabeth was crowned a year later and subsequently gave birth to several more children. Although Henry and Elizabeth’s marriage started out as political, the two grew to genuinely care about each other. Elizabeth also played a somewhat active role in government. In 1502, Elizabeth’s oldest son died and Elizabeth, in an effort to have another heir, got pregnant again at 36—quite advanced for this period. In February 1503, Elizabeth gave birth to a daughter. The daughter died shortly after birth and Elizabeth herself died on 11 February 1503—her 37th birthday. Her husband was greatly affected by her death, becoming increasingly isolated and miserly. He never re-married and himself died just six years later and was buried next to her.

27 notes

·

View notes