#1749-1750

Photo

Portrait of Sarah Eleanore Fairmor by Ivan Vishnyakov, circa 1749-1750

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gown and Petticoat

A womans's gown and petticoat, 1750-55, altered 1870-1910, English; of beige figured silk, c.1749 brocaded, floral motifs

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1749-1750 Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewski - Johanna Elisabeth von Holstein-Gottorf, mother of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia

(Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden)

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

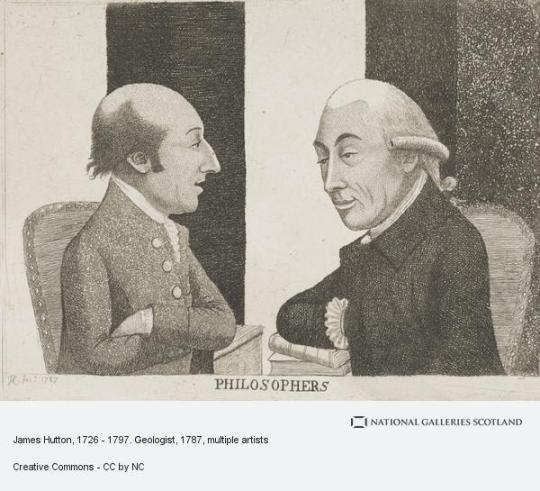

On 26th March 1797, James Hutton, the Scottish chemist and geologist, died.

Farmer and naturalist James Hutton is credited with being the founder of modern geology. The first to determine that the Earth is millions of years old, Hutton believed our planet is continually being formed. James Hutton was born in Edinburgh in 1726. He went on to study medicine and chemistry at Edinburgh University, and in Paris and Leiden. He took his degree in 1749.

In 1750 he returned to Edinburgh and resumed chemical experiments with friend James Davie. Their work on the production of sal ammoniac – a salt used for dying and working with brass and tin – led to a profitable partnership. Hutton moved to Slighhouses, a lowland family farm, in the 1750s. He spent 14 years running the farm. This gave him an interest in how land changed with the forces of wind and rain.

In 1753 Hutton became interested in studying the surface of the earth. He went on to devote his scientific knowledge, powers of observation and philosophical mind to the newly-named subject of ‘geology’.

Hutton went on a geological tour of the north of Scotland with George Maxwell-Clerk (the great-grandfather of the famous physicist James ) in 1764. He let his farms to tenants in 1768 and returned to Edinburgh. Between 1767 and 1774 he was closely involved with the construction of the Forth and Clyde canal.

Travels in Britain and abroad, as well as a time farming in Berwickshire, gave Hutton the opportunity to observe different rocks. He was intrigued to find fossilised shells high above sea level, and puzzled over other geological features. Hutton’s thinking was then influenced by reading about Joseph Black’s experiments with heated limestone, and by the proof of the power of heat demonstrated by James Watt’s steam engines. Hutton began considering the centre of the Earth as a massive heat source, where continuous processes destroy and reform rocks — the 'uniformitarian’ theory of geology. That led to his belief that the Earth was millions of years old.

Other scientists and philosophers vehemently disagreed with him. Many of these were 'catastrophists’ who believed that changes in geology happened as a result of natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions or floods. The debate continued for several decades during the 19th century, until finally geologists became reconciled to Hutton’s theory.

In 1785 Hutton presented his findings to the newly formed Royal Society of Edinburgh. He died on 26 March 1797 and was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh in the part of the graveyard known as the “Covenanters Prison”

Five years after Hutton’s death, mathematician John Playfair published 'Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth’. This volume contained a summary of Hutton’s 'Theory of the Earth’ alongside numerous additional illustrations and arguments.

In a poll, James Hutton was voted the seventh most popular Scottish scientist from the past. It is remarkable that men like Hutton , David Hume, Adam Smith, Dugald Stewart, Thomas Reid, and countless others all came out of Scotland in the same era, all within less than a hundred year period, their thoughts and works were spread throughout an ever growing world as part of the Scottish diaspora, the era became known as The Scottish Enlightenment.

Pics are of Hutton, the statue is on The Scottish Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh and the James Hutton Memorial Garden, which I have to admit have never visited, even though I have regularly taken a shortcut through Viewcraig Gardens, where it is situated.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lady Christian Henrietta Caroline ‘Harriot’ Acland, née Fox-Strangways (1749/1750–1815)

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

National Trust, Killerton

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1741, the Russian ship St. Peter, part of Vitus Bering’s expedition of discovery, shipwrecked on one of the islands while returning from the first European exploration of Alaska. Bering’s scurvy-wracked men spent a miserable winter, killing marine mammals for food and warding off the fearless arctic foxes (Alopex lagopus) that tried to eat the dying. Georg Wilhelm Steller, the expedition’s naturalist, devoted much of his time to a study of the island’s fauna, later published to great interest in Europe. Few Europeans had ever experienced the numbers and variety of marine mammals that the men encountered on these islands. “If I were required to state how many [fur seals] I saw on Bering Island,” Steller wrote, “I should truthfully say that I could not guess -- they were countless, they covered the whole shore.” [...]

---

When the remnants of the expedition arrived in Kamchatka in the summer of 1742, their tales of the abundant sea otters, fur seals, and sea cows sent Russian fur traders (promyshlenniki) from Siberia to hunt in the newly discovered waters. [...] Initially, the promyshlenniki found the animals to be as unbelievably numerous as Steller had reported them to be. The first hunters killed as many as fifty sea otters per day, several gigantic sea cows (used for food and leather) per season, and thousands of the arctic foxes that had once eaten Russians. [...]

---

Beginning with Steller’s two-year visit, hunting had been carried out at an unsustainable rate. The sea otter population entered a serious crash seven years after Steller’s shipwreck -- in 1749 and 1750 -- when at least four crews hunted in the Commanders. In what must have been a vast and ceaseless slaughter, hunters killed at least 1,380 sea otters (roughly a quarter of the entire estimated population) in these two years alone. By 1754 the population had probably dropped below eight hundred animals spread across the two islands -- a decline of 85 percent over twelve years -- numbers low enough that hunters would have had trouble locating the animals at all. In 1757, hunters suddenly began bypassing the Commanders for the Aleutian Islands [...]. Nearly forty years later, Commander Islands’ sea otters still had not recovered from the onslaught of 1749 − 1750. [...]

---

The Russian fur trade in the Pacific differed from the New World European terrestrial fur trades in another way. The Russians, besides trading for furs with the Aleuts, also demanded from them a yearly tribute of furs (called yasak), as they had with all conquered Siberian peoples. The fur traders forced compliance by taking some members of the community hostage and promising their safety only upon delivery of furs. As more and more Aleut communities fell under promyshlennik domination in the course of the eighteenth century, yasak collection naturally increased. At the same time that the supply of sea otters was in steep decline, tribute demands increased. [...]

---

By then, all involved in the trade expected sea otters to disappear rapidly; they no longer expected sea otters to behave like sables. Irkutsk governor Ivan Iakobii reported to Catherine II in 1787 that “we know from many examples that the hunting has decreased substantially each year. There is absolutely no doubt, when one realizes that millions of animals have been taken [in the North Pacific]. One can therefore suppose that in a few years the animals will be completely depleted [...].” By the time the Russian American Company (RAC) was granted a monopoly on the trade in 1799, it too was forced to begin looking immediately for new hunting grounds in southeastern Alaska. [...]

---

Text by: Ryan Tucker Jones. “A ‘Havock Made among Them’: Animals, Empire, and Extinction in the Russian North Pacific, 1741-1810.” Environmental History Vol. 16, No. 4. October 2011. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#this article is great and is actually much more focused on the history of environmentalist thought and the formation of green imperialism#basically about how british and french imperial naturalists observed and responded to russian practices and#and how a sort of Russian Orientalism and prejudice against Russians led the British and French to frame Russians as barbarians#and develop a sort of imperialist justification for conservation but conservation mostly as a means of controlling resources#but also the article is about how naturalists in western europe developed ideas of extinction and conservation in response#therefore inspiring a lot of the Victorian nineteenth century fascination with anitquity and finality and extinction etc

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

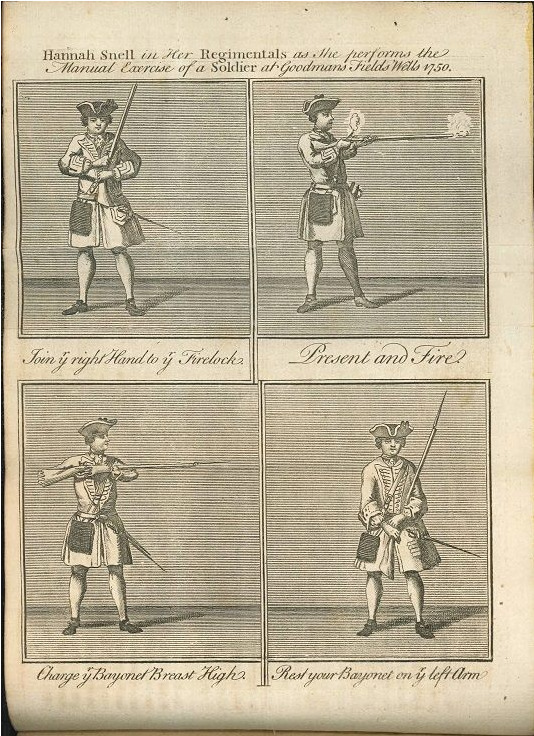

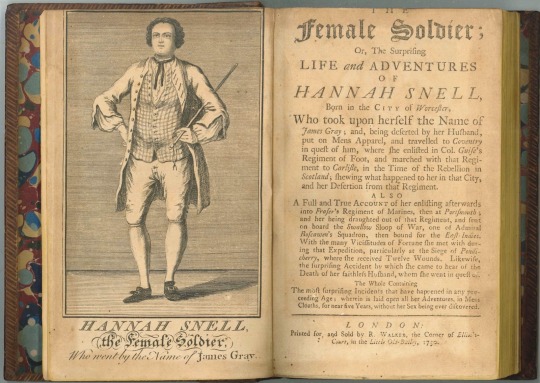

Hannah Snell “The Woman in Men's Cloaths”

Hannah Snell was born on 23 April 1723 in Worcester, England. She moved to London in 1740 and married James Summes, a Dutch Sailor, on 6 January 1744. Two years later their daughter Susannah was born and died after only one year. Her husband had left her while she was still pregnant and now without husband and child she saw no other way out than to look for him.

Hannah Snell, a woman who passed as a soldier. Mezzotint by J. Young, 1789, after R. Phelps. (x)

She borrowed men's clothes from her brother-in-law James Gray and used his name. According to her account, following the death of her daughter, on 23 November 1745, she joined John Guise's regiment, the 6th Regiment of Foot, in the army of the Duke of Cumberland against Bonnie Prince Charlie. She deserted when her sergeant gave her 500 lashes and moved to Portsmouth and joined the Marines. At this point it was not true, because the events and dates she gave, as well as the chronologies of her life, make it unlikely that she served under John Guise.

Rather, after the death of her daughter, she went to Portmouth to look for him and learned that he had been executed for murder. What motivated her to join the Marines is not clear. Some historians suggest that she had hoped to find him at sea or at a naval base and joined the Marines before learning of his death. What is certain, however, is that she boarded HMS Swallow on 23 October 1747 and sailed for Lisbon on 1 November of the same year. In August 1748, her unit was sent on an expedition to capture the French colony of Pondicherry in India. She later also took part in the Battle of Devicotta in June 1749. She was wounded eleven times in the legs and once in the groin. She either managed to treat her groin wound without revealing her sex, or she enlisted the services of a compassionate Indian nurse.

(x)

In 1750, her unit returned to Britain and travelled from Portsmouth to London, where she revealed her gender to her shipmates on 2 June. She asked the Duke of Cumberland, the commander-in-chief of the army, for her pension. She was then honourably discharged and, because of her good service, was promised a pension in November 1750. Hoping for the pension but uncertain that she would receive it, she sold her story in June to Robert Walker, a publisher in London, who published it in two different editions.

Hannah Snell, a woman who passed as a male soldier. Wood engraving, 1750. (x)

Curious about who this woman was, more and more people wanted to see her and so she appeared in public and in theatres in her uniform and told of her adventures, showed her fighting skills and sang marching songs. Three painters painted portraits of her in her uniform and The Gentleman's Magazine also covered her story in July.

Hannah showing her skills (x)

After her pension was approved Hannah retired to Wapping and began running a pub called The Female Warrior or The Widow in Masquerade - sources disagree on this - but it did not last long. She then moved to Newbury in Berkshire in the mid-1750s. In 1759 she married a second time to a man called Richard Eyles, with whom she had two children. And in 1772 she married a third time to a man called Richard Habgood from Welford, also in Berkshire, and they moved to the Midlands. In 1785 she was living with her son George Spence Eyles, a clerk, in Church Street, Stoke Newington, but in that year her pension was withdrawn.

One edition of Hannah’s Story, published by Rober Walker 1750 (x)

She appeared to be suffering from Alzheimer's disease and her health deteriorated gradually but not dramatically. This suddenly changed in 1791. she was admitted to Bethlem Hospital on 20 August and died on 8 February 1792. she was then buried in Chelsea Hospital, which had already been a hospital and let's call it an old people's home for veterans of the British army and also functioned like the Royal Navy Hospital in greenwhich is now even an old people's and nursing home.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johann Sebastian Bach's (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) handwritten personal copy of his Mass in B minor held by the Berlin State Library and added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.

The Mass in B minor (completed in 1749) is widely regarded as one of the supreme achievements of classical music.

Source: Historic Vids / X

youtube

Bach: Mass in B minor - Kyrie I - Herreweghe

#Johann Sebastian Bach#Mass in B minor#Berlin State Library#UNESCO's Memory of the World Register#UNESCO#classical music#Youtube#Baroque period#Baroque style#Baroque era#composer#western classical music

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

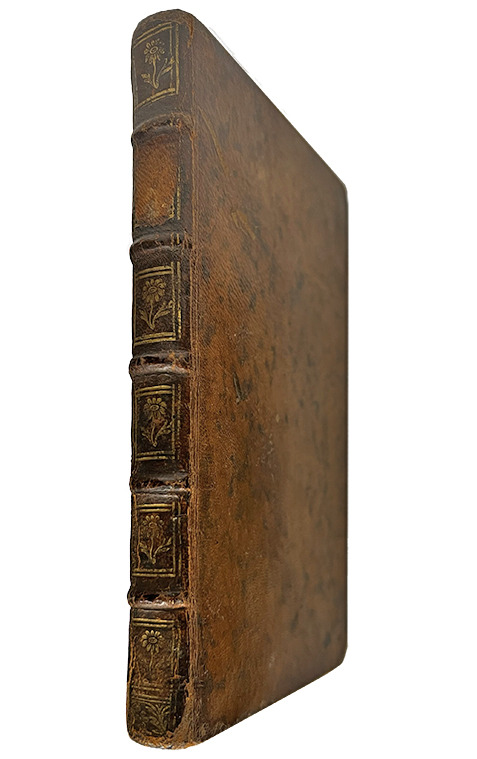

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room!

At the Hardin Library of Health Sciences

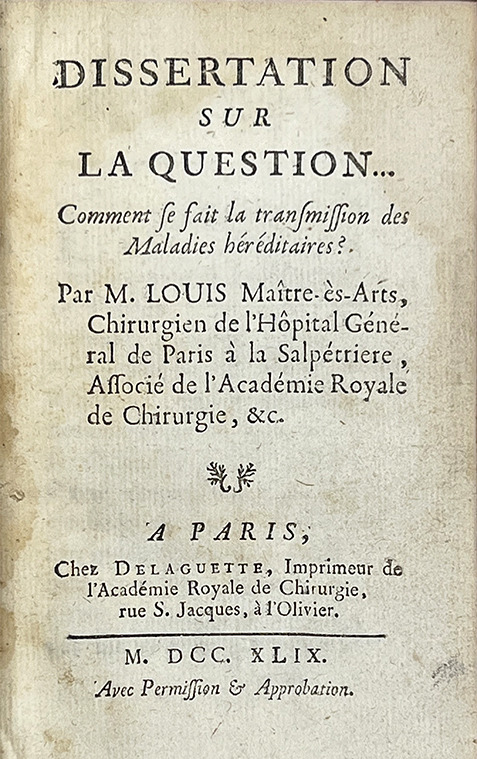

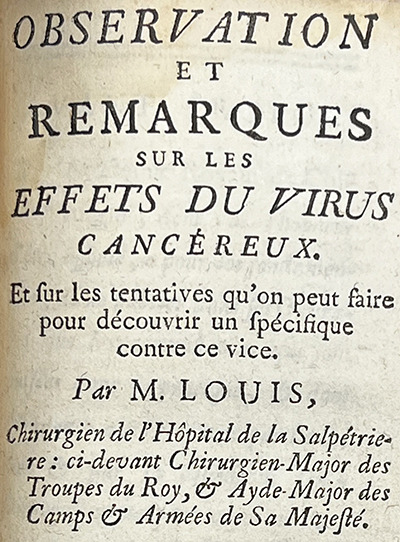

LOUIS, ANTOINE (1723-1792). Dissertation sur la question--comment se fait la transmission des maladies héréditaires? [Dissertation on the question--how are hereditary diseases transmitted?] and Observation et remarques sur les effets du virus cancéreux [Observation and remarks on the effects of the cancer virus], Printed in Paris at Chez Delaguette, 1749. 17 cm tall.

This month we highlight a book (but two works!) by the 18th-century French surgeon, Antoine Louis, who helped change the perception of surgeons in the medical community. We touch on his works on hereditary diseases and cancer, his little-known connection to the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror, and his role in helping to create the modern surgical profession.

Louis was born to a military surgeon family. His father was a surgeon-major, the senior surgeon of a regiment, at a military hospital. Louis apprenticed under his father and by 1743 had joined another regiment as a surgeon himself. He soon went to Paris, though, to further his education at the Salpêtrière hospital, which you may remember from such JMRBR newsletters as "Volume 2, Issue 4." In 1750 he was appointed professor of physiology, holding that position for 40 years.

Louis was at the head of a movement to push back against the negative perception of surgeons driven by physicians. He wrote often, and effectively, to argue for equal status for surgeons. For centuries surgeons were thought of by physicians as, at best, less educated technicians and, at worst, uneducated boors who would cut anything for money.

Although eventually a separate discipline with its own schools, societies, and formal training, surgery in Europe had its roots in the barber-surgeon tradition. Often employed in the military, barber-surgeons used their tools for surgical and dental procedures as well as for cutting hair.

The 16th-century predecessor of Louis, Ambroise Paré, helped lay the groundwork for the modern evolution of surgery into a medical specialty. He challenged surgical dogma at the time and wrote many works, always in French as he did not know Latin, describing his new techniques and inventions.

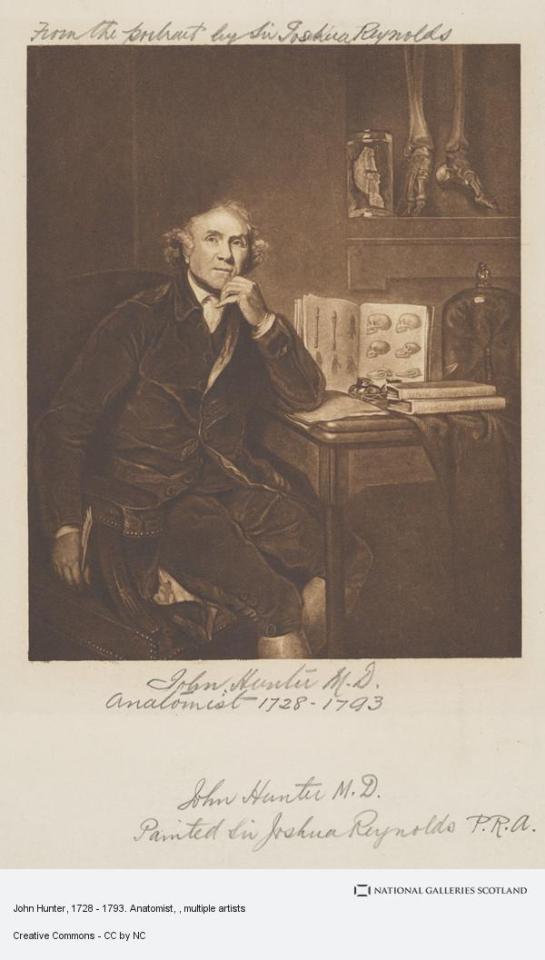

Scottish surgeon John Hunter, a contemporary of Louis, established the empirical foundations of modern surgery. Echoing a common theme among early modern medical pioneers, he rejected the status quo and sought to understand surgical knowledge from the ground up. He based his conclusions on his own observations, experiences, and experiments. With his skill as both an experimentalist and writer, Hunter nearly singlehandedly set surgery on the path to its modern place in medicine.

By the 19th century, barber-surgeons ceased to exist and surgeons were well-trained doctors who chose surgery as a specialization.

Louis was not afraid to put his money where his mouth was. Upon the completion of his stint at Salpêtrière, he could have slid right into a position at the college of Surgery, but instead, he wrote and publicly defended his thesis, Positiones anatomicae et chirurgicae(1749). Both of which he accomplished in Latin, thereby demonstrating that surgeons were as liberally educated as their physician colleagues.

While also performing surgeries, writing, and maintaining a busy administrative calendar, Louis found time to invent and improve surgical instruments. His renown eventually led to an association with the most infamous period in French history. A physician opposed to capital punishment petitioned the National Assembly (formed shortly after the French Revolution) to advocate for a more "humane" way to execute criminals.

This would be accomplished by using a machine designed to quickly decapitate them. The Assembly eventually petitioned Louis to design and build it. Originally referred to as the Louisette, it eventually adopted the name synonymous with the Reign of Terror - the Guillotine, named after the physician who originally proposed its use, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin.

Louis wrote and published throughout his life, including several biographies of other surgeons, Encyclopédie entries, and pioneering works on medical jurisprudence. Two boxes of unpublished works were found while cataloging his belongings after his death. The books highlighted here are two of his earlier publications. Observation et remarques sur les effets du virus cancéreux is an interesting piece on cancerous growths and remedies, in which Louis refers to cancer as a virus. We now know of several viruses that can lead to cancer.

Our copy is an adorable little book with beautiful marbled endpapers, a closeup of which you can see above. The contemporary sheepskin cover shows that the book has lived a busy life. It is a deep, rich brown color with several gilt flowers along the spine. The paper is in excellent condition, showing few signs of age or damage.

#medical history#medicine#surgical#french revolution#university of iowa#rare books#jmrbr#hardin library#libraries#antoine louis

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

name every witch that’s been hunted, I’ll wait /j

Veronika of Desenice d. 1425

Theoris of Lemnos before 323 BC

Liu Ju d. 91 BC

Petronilla de Meath c. 1300–1324

Stedelen d. c. 1400

Kolgrim c. d. 1407

Matteuccia de Francesco d. 1428

Agnes Bernauer c. 1410–1435

Guirandana de Lay d. 1461

Gentile Budrioli d. 14 July 1498

Narbona Dacal d. 1498

Janet, Lady Glamis d. 1537

Gyde Spandemager d. 1543

Lasses Birgitta d. 1550

Agnes Waterhouse c. 1503–1566

Polissena of San Macario d. 1571

Janet Boyman d. 1572

Gilles Garnier d. 1573

Soulmother of Küssnacht d. 1577

Violet Mar d. 1577

Thomas Doughty d. 1578

Ursula Kemp c. 1525–1582

Elisabeth Plainacher 1513–1583

Walpurga Hausmannin d. 1587

Anna Koldings d. 1590

Rebecca Lemp d. 1590

Anne Pedersdotter d. 1590

Kerstin Gabrielsdotter d. 1590

Agnes Sampson d. 1591

Marigje Arriens c. 1520–1591

Witches of Warboys d. 1593

Allison Balfour d. 1594

Jean Delvaux d. 1595

Andrew Man d. 1598

Pappenheimer Family d. 1600

Mary Pannal d.1603

Merga Bien 1560s–1603

Mechteld ten Ham d. 1605

Nyzette Cheveron d. 1605

Franziska Soder d. 1606

Elin i Horsnäs d. 1611

Alice Nutter 1612

Pendle witches d. 1612

Evaline Gill d. 1616

Elspeth Reoch d. 1616

Margaret Cubbon (or Ine Quaine) d. 1617

Witches of Belvoir d. 1618

Sidonia von Borcke 1548–1620

Christenze Kruckow 1558–1621

Anne de Chantraine 1601–1622

Jón Rögnvaldsson d. 1625

Katharina Henot 1570–1627

Johannes Junius 1573–1628

Urbain Grandier 1590–1634

Johann Albrecht Adelgrief d. 1636

Maren Spliid c. 1600–1641

Elizabeth Clarke c. 1565–1645

Adrienne d'Heur 1585–1646

Alse Young c. 1600–1647

Margaret Jones 1648

Mary Johnson c. 1648

Alice Lake[13] 1620 – c. 1650

Mrs. Kendall[13] c. 1650

Jeane Gardiner d. 1651

Michée Chauderon d. 1652

Goodwife Knapp[15] d. 1653

Ann Hibbins 1656

Marketta Punasuomalainen 1600s–1658

Daniel Vuil d. 1661

Anna Roleffes c. 1600-1663

Goodwife Greensmith[13] d. 1663

Isabella Rigby d. 1666

Steven Maurer d. 1666

Lisbeth Nypan c. 1610–1670

Thomas Weir 1599–1670

Märet Jonsdotter 1644–1672

Anna Zippel d. 1676

Brita Zippel d. 1676

Malin Matsdotter 1613–1676

Anne Løset d. 1679

Peronne Goguillon d. 1679

Catherine Deshayes c. 1640–1680

Antti Tokoi d.1682

Ann Glover d. 1688

Jacob Distelzweig d. 1690

Alice Parker d. 1692

Ann Pudeator d. 1692

Bridget Bishop c. 1632–1692

Elizabeth Howe 1635–1692

George Burroughs c. 1650–1692

George Jacobs 1620–1692

Giles Corey c. 1611–1692

John Proctor c. 1632–1692

John Willard c. 1672–1692

Margaret Scott d. 1692

Martha Carrier d. 1692

Martha Corey 1620s–1692

Mary Eastey 1634–1692

Mary Parker d. 1692

Mima Renard d. 1692

Rebecca Nurse 1621–1692

Sarah Good 1655–1692

Sarah Wildes 1627–1692

Susannah Martin 1621–1692

Wilmot Redd 1600s–1692

Anne Palles 1619–1693

Viola Cantini 1668–1693

Paisley witches d. 1697

Elspeth McEwen d. 1698

Anna Eriksdotter 1624–1704

Laurien Magee 1689-1710

Mary Hicks 1716

Janet Horne d. 1727

Catherine Repond 1662–1731

Helena Curtens 1722–1738

Bertrand Guilladot d. 1742

Maria Renata Saenger von Mossau 1680–1749

Maria Pauer 1730s–1750

Ruth Osborne 1680–1751

Ursulina de Jesus d. 1754

Anna Göldi d. 1782

Maria da Conceição d. 1798

Leatherlips 1732–1810

Barbara Zdunk 1769–1811

Ama Hemmah d. 2010

Amina bint Abdulhalim Nassar d. 2011

Muree bin Ali Al Asiri d. 2012

Ahmed Kusane Hassan d. 2020

#hope it wasn't a too long wait /j#[.asks]#anonymous#and it's obviously not all of them I don't think we even know all of them#long post

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Managed to make it to the Dicken's Fair this year! Twas the last three hours of the closing day but we still got our meat pie (delicious!), caught Brass Farthing (enjoyable even with only 5 members in attendance), basked in the glory of Edger Allen Poe's recitations, and caught the last run of 'The Naming of Uranus'.

The play was, as the name suggests, about the naming of the planet and an unending joke about its pronunciation. Was also a musical with an all ladies cast performing mostly male roles. It was dumb but it was fun and I did laugh out loud several times. It also sparked in my heart a desire to familiarize myself with more historical women of note.

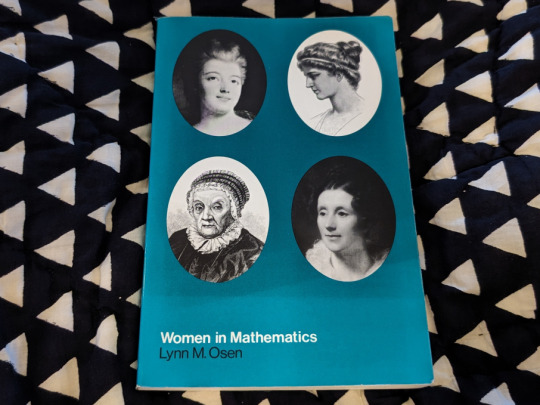

Came home and unearthed the 1975 book Women in Mathematics by Lynn M. M Osen that I'd picked up years ago at a Friends of the Library booksale. Had only read one entry prior (the very depressing tale of Hypatia) and breezed through the rest of it in two days. Kinda' enjoyable, to my surprise?

The typesetting is rather hideous (blindingly white paper, funky margins) but easy to read language with very high level takes on various ladies. What I particularly enjoyed was how old several of the women were when doing a majority of their work. Enjoyed learning about Mary Somerville (1780-1872) and Caroline Herschel (1750-1848, whose brother discovered Uranus). I kinda' want to know more about Emilie de Breteuil (1706-1749) and am bummed I can't find a free, translated version of her "Discours sur le Bonheur" online.

Anyway, note to self: I should get ahold of a copy of Seduced by Logic by Robyn Arianrhod and read that next.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis XV era dress:

Top left: 1739-1749 Maria Felice Tibaldi by Pierre Subleyras (Worcester Art Museum - Worcester, Massachusetts, USA). From tumblr.com/blog/view/antiquelaceartist/689987624228782080 910X1211 @72 368kj.

Top right: 1743 Marquise de Castellane with her Embroidery by Jacques-André-Joseph Aved (Manchester Art Gallery - Manchester Art Gallery - Manchester, Greater Manchester, UK). From tumblr.com/blog/view/costumedufilm 942X1200 @72 400kj. Manchester was historically part of Lancashire.

Second row left: 1746 Louise Henriette Gabrielle de Lorraine, Princess of Turenne and Duchess of Bouillon by Jean-Marc Nattier (Versailles). From tumblr.com/blog/view/roehenstart 1538X1953 @72 999kj.

Second row right: 1750s Woman by Maurice Quentin de La Tour (Harvard Art Museums - Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). From tumblr.com/blog/view/catherinedefrance 858X1024 @72 241kj.

Third row: Maria Caterina Brignole, Princess of Monaco by ? (location ?). From tumblr.com/blog/view/down-the-rabbith0le/161758053255; blurred background and neckline area 1021X1280 @72 370kj.

Fourth row left: 1759 Madeleine Barberie de Courteille by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum - Braunschweig, Niedersachsen, Germany). From tumblr.com/blog/view/history-of-fashion 769X921 @72 255kj.

Fourth row right: 1760 Mrs. Robert Brudenell by Sir Joshua Reynolds (Fogg Museum, Harvard University - Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). From tumblr.com/blog/view/sims4rococo76 1968X2400 @72 1.2Mj.

Fifth row: 1765 The Roffey Family by Sir Joshua Reynolds (Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery - Birmingham, West Midlands, UK). From tumblr.com/blog/view/catherinedefrance; erased spots w Pshop 2048X1637 @72 949kj.

Sixth row: 1766 The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (Wallace Collection - London, UK). From Google search leading to twitter.com/cowboycaps; erased most obvious spots & cracks w Pshop & mildly cropped 3158X4050 @72 7.5Mj.

Bottom: Lady, half-length, in a dark green velvet dress and white chemise, wearing a white headdress by Hieronymus van der Mij (auctioned by Christie's). From tumblr.com/blog/view/shewhoworshipscarlin 2048X2560 @72 1.3Mj.

#Louis XV fashion#Rococo fashion#1730s fashion#1740s fashion#1750s fashion#1760s fashion#curly hair#cap#attifet#bergere#Pierre Subleyras#Jacques-André-Joseph Aved#Marquise de Castellane#Louise Henriette Gabrielle de Lorraine#Jean-Marc Nattier#Maurice Quentin de La Tour#Maria Caterina Brignole#Madeleine Barberie de Courteille#jean-baptiste greuze#Mrs. Robert Brudenell#Joshua Reynolds#the swing#Jean-Honoré Fragonard#Roffey Family#family portrait#Hieronymus van der Mij

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western Art Music History

I. EARLY MUSIC PERIOD

Medieval (500—1400), Rennaisance (1400— 1600)

Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli, Kyrie (1567) *

II. COMMON PRACTICE PERIOD Baroque Era Music (1600—1750)

Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610. Nigra Sum (1610)

Lully’s Armide Passacaille (1686)

Purcell’s Dido’s Lament (When I Am Laid in Earth) from Dido and Aeneas (1688) ****

Charpentier’s Te Deum, H.146 in D major (1692)

Pachelbel’s Canon in D major (1694)

Corelli’s Sonata for Violin and Basso Continuo, Op.5: No.12 in D minor (1700)

Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 (1707) * #10

Vivaldi’s Gloria RV 589 (1708) * #2

Vivaldi’s Violin Suite Concerto No.1 in D major, Op.3 (1711) * #3

Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582 (1713) * #4

Handel’s Water Music (1717) * #2

Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No.5 in D major, BWV 1050 (1721) * #9

Bach’s Prelude in C major from Well Tempered Clavier Book 1 (1722) * #3

Bach’s Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004 (1723) * #6

Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (1723) * #1

Handel’s Giulio Cesare, HWV 17 (1724) * #9

Petzold’s Minuet in G minor (formerly attributed to J.S. Bach as BWV Anh.II 115) (1725)

Vivaldi Concerto for Mandolin in C major RV425 (1725) * #4

Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion, BWV 244 Part 1 (1727) * #2

Handel’s Four Coronation Anthems (1727) * #4

Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins, Strings and Continuo in D minor, BWV 1043 (1731) * #7

Telemann’s Suite in A minor for recorder, strings, harpsichord, and basso continuo, TWV55:A3 (1735)

Rameau’s Les Indes Galentes (1735)

Handel’s Organ Concerto No. 13 “The Cuckoo & Nightingale” (1738) * #8

Handel’s Concerto Grosso in G minor, Op. 6, No. 6 (1739) * #10

Handel’s Concerto Grosso in B flat major, Op. 6, No. 7 (1739) * #6

Handel’s Messiah, The Hallelujah Chorus (1741) * #1

Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Aria (1741) * #5

Handel’s Solomon, HWV 67 (1748) * #7

Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus , HWV 63 (1749) * #5

Bach’s Mass in B minor, BWV 232. Sanctus (1749) * #1

Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks , HWV 351 (1749) * #3

Classical Era Music (1750—1830)

Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)

Soler’s Fandango

Boccherini’s Minuet from String Quintet in E, Op. 11, No. 5, G 275. (1775)

Salieri’s Les Danaides (1784)

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.20 in D minor, K.466 (1785) * #4

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.21 in C major (1785) * #9

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.24 in C minor, K.491 (1786) * #10

Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (1786) * #2

Mozart’s Don Giovanni, K.527 (1787) * #1

Mozart’s String Quintet No.4 in G minor, K516 (1787) * #7

Mozart’s Symphony No.40 in G minor (1788) * #5

Mozart’s Symphony No.41 in C major, K.551 “Jupiter” (1788) * #3

Mozart’s The Magic Flute, K.620 (1791) * #8

Kozeluch’s Symphony in G minor, Op.22 No.3 (1790’s)

Clementi’s Sonatina, Op.36 No.6 in D major (1795)

Haydn’s The Heavens are Telling the Glory of God (Creation) (1796) *

Beethoven’s Symphony No.3 in E flat major, Op.55 (Eroica) (1804) * #4

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G major, Op.58 (1806) * #10

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No.23 in F minor, Op.57 (Appassionata) (1807) * #5

Beethoven’s Symphony No.5 in C minor, Op.67 (Fate) (1808) * #2

Beethoven’s Symphony No.6 in F major, Op.68 (Pastoral) (1808) * #8

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat major, Op.73 (Emperor) (1811) * #6

Rossini’s Barber of Seville (1816)

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, Op.111 (1822) #9

Beethoven’s Symphony No.9 in D minor, Op.125 (Choral) Ode to Joy (1824) * #1

Beethoven’s String Quartet No.13 in B flat major, Op.130 (1825) #7

Beethoven’s String Quartet No.14 in C sharp minor, Op.131 (1826) * #3

Romantic Era Music (1804—1949)

Schubert’s Erlkonig for solo voice and piano (1815) * #10

Schubert’s Piano Quintet in A major, D.667 “Trout” (1819) * #7

Weber’s Der Freischutz Overture (1821)

Schubert’s Symphony No.8 in B minor “Unfinished” (1822) * #5

Schubert’s Fantasie in C major, Op.15, D.760 “Wanderer Fantasy” (1822) * #9

Schubert’s Die Schone Mullerin, Op.25, D.795 (1823) * #8

Schubert’s String Quartet No.14 in D minor “Death and the Maiden” (1824) * #6

Schubert’s Winterreise (1828) * #1

Schubert’s String Quintet in C major, D.956 (1828) * #2

Chopin’s Etudes, Op.10 (1833) * #2

Berlioz’s Symphonie Fanstastique (1830) *

Chopin’s Ballade No.1 in G minor, Op.23 (1836) * #7

Chopin’s Nocturnes, Op.27 (1837) * #3

Chopin’s Preludes, Op.28 (1839) * #1

Chopin’s Piano Sonata No.2 in B flat minor, Op.35 (1839) * #8

Schumann’s Dichterliebe, Op.48 (1840) * #2

Schubert’s Symphony No.9 in C major, D.944 “Great” (1840) * #3

Chopin’s Fantaisie in F minor, Op.49 (1841) * #9

Chopin’s Polonaise No.6 in A flat major, Op.53 “Heroic” (1842) * #5

Schumann’s Piano Quintet in E flat Major, Op.44 (1842) * #3

Mendelssohn’s Wedding March in C major from Incidental Music Op.61 to “Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1842) *

Wagner’s Tannhauser (Pilgrim’s Chorus) (1843) * #7

Chopin’s Mazurkas (1843) * #4

Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.54 (1845) * #1

Chopin’s Barcarolle in F sharp major, Op.60 (1846) * #10

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 (1845) *

Chopin’s Waltzes, Op.64 (1847) * #6

Wagner’s Lohengrin Prelude to Act III (Bridal Chorus) (1848) * #6

Schumann’s Symphony No.3 in E flat Major “Rhenish”, Op.97 (1850) * #4

Verdi’s La Traviata (1853) * #5

Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor, S.178 (1854) * #1

Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries (1856) * #2

Wagner’s Libestod from “Tristan und Isolde” (1859) * #1

Brahms’ Piano Quartet No.1 in G minor, Op.25 (1861) * #10

Brahms’ Piano Quintet in F minor, Op.34 (1865) * #8

Wagner’s The Mastersingers of Nuremberg Prelude to Act 1 (1867) * #5

Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.16 (1868) *

Saint-Saens’ Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, Op.22 (1868) * #2

Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem, Op.45 (1868) * #6

Verdi’s Aida (Opus Arte) (1871) * #2

Brahms’ Variation on a Theme by Haydn (Saint Anthony Variations) * #9

Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov (1873) *

Verdi’s Messa Da Requiem (1874) * #3

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1 in B flat minor, Op.23 (1875) * #4

Bizet’s Carmen (1875) *

Wagner’s Gotterdammerung (1876) * #3

Brahms’ Symphony No.1 in C minor, Op.68 (1876) * #7

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.4 in F minor, Op.36 (1877) * #7

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op.35 (1878) * #8

Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, Op.24 (1879) * #9

Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D major, Op.77 (1879) * #5

Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.2 in B flat major, Op.83 (1881) * #2

Wagner’s Parsifal Act 1 Prelude 1 (1882) * #4

Bruckner’s Symphony No.7 in E major (1883) *

Brahms’ Symphony No.3 in F major, Op.90 (1883) * #4

Brahms’ Symphony No.4 in E minor, Op.98 (1884) * #1

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet “Fantasy Overture” (1886) * #6

Franck’s Sonata in A-major for Violin and Piano (1886)

Saint-Saens’ Symphony No.3 in C minor, Op.78 “Organ” (1886) * #1

Verdi’s Otello (1887) * #1

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.5 in E minor, Op.64 (1888) * #10

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (1888) *

R.Srauss’ Don Juan, Op.20 (1889) * #5

Faure’s Requiem in D minor, Op.48 (1890) *

Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty Ballet Suite Op.66 Act II Panorama (1890) * #5

Brahms’ Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op.115 (1891) * #3

Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite (1892) * #2

Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C sharp minor, Op.3, No.2 (1892) * #3

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.7 in E flat major (1892) *

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.6 in B minor, Op.74 “Pathetique” (1893) * #1

Dvorak’s Symphony No.9 in E minor, Op.95 “From the New World” (1893) *

Verdi’s Falstaff (1893) * #4

Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1894) *

Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (1895) * #3

R.Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Op.28 (1895) * #1

Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B minor, Op.104, B.191 (1895) *

R.Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathrustra, Op.30 (1896) * #2

Puccini’s La Boheme (1896) *

III. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY 20th Century (1900—2000)

Mahler’s Symphony No.2 in C minor “Resurrection” (1895) * #2

R.Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben, Op.40 (1898) * #3

Sibelius’ Finlandia Op. 26 (1900) * #2

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 in C minor, Op.18 (1901) * #2

Mahler’s Symphony No.5 in C sharp minor (1902) * #1

Sibelius’ Symphony No.2 in D major, Op.43 (1902) * #1

Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) *

Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D minor, Op.47 (1904) * #3

Debussy’s La Mer (1905) *

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.3 in D minor, Op.30 (1909) * #1

Mahler’s Symphony No.8 in E flat major (1910) * #5

Stravinsky’s The Firebird (1910) * #3

Mahler’s Symphony No.9 in D major (finale of D-flat major) (1910) * #3

Williams’ Tallis Fantasia (1910) *

R.Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier, Op.59 (1911) * #4

Stravinsky’s Petrushka (1911) * #2

Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (1911) * #4

Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe “Choreographic Symphony” (1912)

Debussy’s Preludes (1913) *

Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) * #1

Sibelius’ Symphony No.5 in E flat Major, Op.82 (1915) * #4

Prokofiev’s Symphony No.1 in D major, Op.25 (1918) * #3

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No.3 in C major, Op.26 (1921) * #2

Saint-Saens’ The Carnival of the Animals (1922) * #3

Stravinsky’s Les Noces (1923) * #5

Shostakovich’s Symphony No.1 in F minor, Op.10 (1925) * #4

Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass (1927)

Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (1930) * #4

Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No.1 in C minor, Op.35 (1933) * #5

Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler (1934) *

Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, Op.64 (1935) * #4

Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, Op.67 (1936) * #5

Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5 in D minor, Op.47 (1937) * #2

Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra (1943) *

Copland’s Appalachian Spring (1944) *

Prokofiev’s Symphony No.5 in B flat major, Op.100 (1944) * #1

Shostakovich’s Symphony No.10 in E minor, Op.93 (1953) * #1

Shostakovich’s String Quartet No.8 in C minor, Op.110 (1960) * #3

Britten’s War Requiem, Op.66 (1962)

Contemporary (1975—Current)

#music#music history#art history#list#videbi.tumblr.com#lists#favorites#art list#music list#classical music list#western art

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ab. 1749-1750 Unknown artist - Helen Murray of Ochtertyre

(Private collection)

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

13th February 1728 saw the birth of John Hunter, the Scottish physician and anatomist.

Born at Long Calderwood, his actual birth date is unknown, another source gives July 14th but the majority plump for February 13th.

Surprisingly Hunter never completed a course of studies in any university, and, as was common for surgeons during the 18th century, he never attempted to become a doctor of medicine. He went to London in 1748 to assist in the preparation of dissections for the course of anatomy taught by his brother William, a famed obstetrician. In the winters he studied anatomy in his brother’s dissecting rooms, and in the summers of 1749 and 1750 he learned surgery from William Cheselden at Chelsea Hospital.

In 1753 he was elected a master of anatomy at Surgeon’s Hall, responsible for reading lectures. He began his own private lectures on the principles and practice of surgery in the early 1770s. In addition, he had teaching duties from 1768 at St. George’s Hospital, to which he had been elected surgeon in 1758. In 1760 Hunter accepted a commission as an army surgeon. He returned to London in 1763, where he continued in private practice until his death. In 1776 he was named surgeon extraordinary to King George III.

Hunter not only made specific contributions of great importance in surgery but also attained for surgery the dignity of a scientific profession, basing its practice on a vast body of general biological principles. In an attempt to demonstrate that gonorrhea and syphilis are manifestations of a single disease, he inoculated a subject (sometimes said to have been himself) with pus from a person with gonorrhea. The subject developed symptoms of both diseases.

Hunter wrote a number of books on surgery throughout his life, he owned a house in London's Earls Court that had large grounds which were used to house a collection of animals including 'zebra, Asiatic buffaloes and mountain goats', When the animals died he would boil the bones down and use them for animal anatomy, a newspaper article reported that many animals there were 'supposed to be hostile to each other but . . . in this new paradise, the greatest friendship prevails', and he may have been the inspiration for the Doctor Dolittle literary character.

Hunter's death in 1793 was due to a heart attack brought on by an argument at St George's Hospital concerning the admission of students. He was originally buried at St Martin-in-the-Fields, but in 1859 was reburied in the north aisle of the nave in Westminster Abbey, reflecting his importance to the country.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1749-1750.

The cities of Philadelphia and Boston, heavily influenced by religious intolerance, attempted to ban all forms of show business.

3 notes

·

View notes