#1795

Photo

Court Suit

1790s

United Kingdom

Victoria & Albert

#fashion history#historical fashion#1790s#regency era#menswear#mensfashion#regency fashion#regency#floral#flower print#silk#linen#cotton#embroidery#british#united kingdom#18th century#1790#1795#1799#court suit#v and a#v and a museum#popular

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch (1795) by Henry Raeburn

#The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch#1790s#1795#Henry Raeburn#painting#art#skating#ice skating#Miss Cromwell

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

A silk round gown from 1795

From the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Dress.

Date: 1795-1805

#fashion history#history of fashion#dress#fashion#18th century#18th century fashion#18th century dress#19th century fashion#19th century#19th century dress#1795#1805

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Partitions of Poland - 1792, 1793, 1795.

by aresten_dmp

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Cotton Coat, 1795-1805, French.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#beige#cotton#coat#extant garments#french#1790s#1795#1790s France#1790s extant garment#1790s coat#1790s menswear#V&A

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me at the end of every social interaction:

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

▪︎Micromosaic Two-Handled Vase.

Artist/Maker: Nicola de Vecchis (Rome, 1795-1800)

Date: 1795-1800

Medium: Marble, hard stone.

#decorative arts#history#history of art#19th century#19th century art#18th century#18th century art#mosaic#Two-Handled Vase#vase#Nicola de Vecchis#1795#1800

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georges – "What If" or an Alternative Life

We all know how the life of Georges de La Fayette, only son of Adrienne and Gilbert turned out. Born into a life of privilege, separated for the first time from his family as a young boy to make sure that his father’s status would not interfere with his studies, he later had to flee with his tutor into the mountains and then to America. In America he was a constant wanderer before returning to France and joining his family in exile in Danish-Holstein. The family was finally able to return to France for good, Georges joined the Army, married, had children, became a politician, returned with his father to America in 1824/25 and finally inherited his title as Marquis de La Fayette – just like his two sons later inherited the title from him.

While his father, his mother and his sisters were all imprisoned at various points in time for various reasons and durations, Georges remained free and was able to live, relatively speaking, “comfortably” in America. But let us imagine for a moment how his life could or would have looked like if some things had been different. Because Georges was a family man – even as a grown man he lived with or near his parents (granted, their living arrangements were normally quite spacious, so …), he married the daughter of one of his father’s friends and colleagues, he followed his fathers into the military and in politics, he cared for his mother, he accompanied his father to America – what would happen if his family had died during the French Revolution? Not only his mother and father but maybe even his sisters? Chances were rather high, Adriennes life was threatened by illness and the guillotine (her grandmother, mother and sister were all guillotined) and La Fayette’s life was threatened by illness, the French warrant for his arrest and his status as a Prisoner of War in both Prussia and Austria.

This questions “how would Georges’ life look like” is not completely theoretical. When Adrienne send her son to America, she wrote both to James Monroe and to George Washington and her letters make it clear that she had planned for the eventuality that Georges maybe had to stay for a very long time in America.

Adrienne wrote in an undated letter, probably from November of 1794, to James Monroe:

I ask him kindly to look after my son. I want him to finish his education in an American house of commerce. It would appear to me preferable to set him up at the residence of a consul of the United States. I want him to join their navy, and if it is absolutely impossible for him to begin his first line of duty at sea on an American vessel, I would have him serve on a French merchant ship.

I encourage the minister of the United States to recall that my son was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1785, and that he still has his certificate as a citizen of that state. I foresee therefore no difficulty in his entering the service of this second country, friend and ally of the French Republic.

Papers of James Monroe, 3: 165; Bookmen’s Holiday, x: 20

She wrote secondly in a letter to George Washington on April 23, 1795:

Sir, I send you my son. (…) it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. (…) While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. (…) My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. (…)

Noailles Lafayette

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 317-322.

I shortened the letter in some parts but there is a complete version under the cut for everyone who is interested.

Adrienne gives very detailed instructions, how Georges should be brought up. In short, she wants him to:

Continue his education under Frestel’s tutelage, without too much ado

Start an apprenticeship, I believe, in a house of commerce

Work on an American merchant ship, or, if that is not possible, on a French merchant ship

Be the picture-perfect American citizen without forgetting his identity as a Frenchman

This is all pretty straight forward and we could end our little thought experiment here and take Adrienne’s instructions as the alternative life Georges could have lead. But I would like to elaborate on some aspects.

Félix Frestel

See, on this blog we appreciate Festel and all that he did. Adrienne herself wrote it in the letter to Washington how much the La Fayette’s owned to Frestel. He was Georges tutor long before the Revolution and likely also lived with him during this time. By all accounts he and Georges were close and Georges’ parents also liked and respected Frestel a lot. He risked his personal safety to hide George, helped Adrienne when her fate hung in the balance, he uprooted his entire life and left a family that he “dearly loved” to follow Georges to America – friendship and all things considered, this went clearly beyond the call of duty of a tutor. Adding to that my suspicion that he was not paid during the French Revolution. Both from a logistical and a financial point, paying Frestel would have been difficult and while we have letters from Adrienne to Monroe, asking him to do certain financial transactions for her, there is not letter from her reminding or asking him to pay Frestel. This is certainly no conclusive evidence but I have a very strong hunch.

In America, Frestel was father, friend and teacher for Georges and I am of the firm believe that he would not have easily deserted the boy, even if their stay in America would have been a longer one. I can think of two possible scenarios. One possible scenario would be that Frestel stayed with Georges until he boy would have reached his majority and finished his education in so far as that he was settled with an American merchant firm and learning there. Frestel might have returned then to France – he was free to do so, there was no warrant for his arrest and his name was not on the list of émigrés – and be reunited with his family. Since he was such a loyal soul and very devoted to his pupil, I could imagine him doing what Adrienne in reality did. Going back to France and trying to reclaim the possessions of the La Fayette family for Georges.

In the second scenario, Frestel decides to stay in America, possible because he had started his own family there. When he left France, he was unmarried and childless. It was therefor very possible for him to fall in love in America and decided to stay there with his family. Just as well he could take his wife and potential children with him back to France.

The Merchant Navy

While first reading Adrienne’s letters I found it quite peculiar that she was so insistent on the merchant navy. The merchants trade is one thing, but the service on a merchant ship means a live at sea and some potential dangers that you do not have, if you sit on dry land behind your desk. It could have been Georges expressed desire but since later in France as an adult he choose the Army over the Navy (and there is no indication that he ever considered the navy), I am somewhat doubting that. Life at sea however promised “adevntures”, comradery and occupation – all things that Georges would have needed and liked. Under British law, crew members of merchant ships were often pressed into the military service due to their skills and experiences. American law was different in that regard and Georges would not have worked as a common sailor, so he should have been all good on that front. Being at sea for long stretches of time was also making social engagements difficult. Adrienne had seen what politics can due to peaceful family life and she maybe intended to set Georges up in way where he would not join the politics of his time.

Being an American – Being a Frenchman

Adrienne herself wrote that she hopes her son “preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison”. Later in life, La Fayette wrote in a letter to his son that they should never forget, no matter what had happened or will happen, France is their country and their home. Georges was born and breed in Paris and he was a patriot. In the real turn of events, he would go on risking his life for France. The question therefor is, would he stay in America or return to France? Both are very real possibilities but, in our scenario, I lean more towards staying in America. We assume that his close family is dead (and with that more or less all family members on his father’s side) and many of his Noailles relatives were also dead or had fled the country (his mother’s father for example, he settled in Switzerland). He had extended family that settled into exile in Wittmold but even in reality he only joined them once his sisters and parents were freed and settled there as well. This extended family alone did not seem to be such a huge pull-factor for him. In our scenario he has nothing to return to, no family, no money, no title, no land – even if we assume that Frestel or Georges managed to get some of the family’s possessions back, they would have been empty, void of life and happiness. They would have been shadows, painful reminders of his former life and all that he had lost. Georges was utterly devoted to his family and to his father in particular. I do not think that he could just let go and start over without constantly lingering in the past. But then again, he was French. France was his home and everything that was left from his family was there in France. That again leads us to two possible scenarios.

In the first one, Georges stays in America. If someone was able to get some or all of the family’s former holdings back, he would maybe sell them and use the money to provide for the family he would (absolutely and definitely) start in America. He maybe would even start his own house of commerce. He could also use some of the money to provide for his father’s elderly widowed aunt still living in France. La Fayette had loved her dearly and vice versa. She would have been too old to come to America but Georges could find other means of making sure she was comfortable. He would inherit his father’s titles and probably not use them much, if at all, while in America. Instead referring to his father as “General La Fayette”

In the other scenario, Georges return to France, either with a wife he married while in America or he finds himself a wife in France. Either way, the girl in question would likely been the sister/daughter/niece/etc. of one of his father’s acquaintances. I could imagine that in France, and especially in Paris, even while serving in the merchant navy, there would have been high chances of Georges being caught up in his “old life”. In this scenario, I can very well see Georges enter politics and most importantly bump heads with Napoléon, just as his father would have done. But where Georges had his father’s opinions and views, he did not had his father later “immunity” towards Napoléon’s antipathy.

Anyway, this whole post has turned into a long “what if” rambling but if you made it to this point, I would be really interested to hear your opinions!

Adrienne to George Washington, April 18, 1795

Sir, I send you my son. Although I have not had the consolation of being listened to nor of obtaining from you those good offices which I thought likely to bring about his father’s delivery from the hands of our enemies, because your views were different from mine, nevertheless my reliance on your kindness is not diminished, and it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. Notwithstanding all the perils he encountered on his way, he made known to M. Morris the horrible situation I was in, and, after having had the courage to traverse the whole of France in those times of horror, following a prisoner, who was to all appearances devoted to death, he animated the zeal of the American minister to whose applications I probably owe that my sacrifice was deferred until the revolution of the 10th of Thermidor [July 28]. He will tell you that I have never given a pretext for any accusation against me, that my country can reproach me with nothing, and I myself will tell you that it is near him and with him that my son invariably learnt, even in the depth of misery, to discern between liberty and the horrors to which its name has been associated. While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. I ardently wish M. Washington to know what he is, and how much we are indebted to him. A letter will very in sufficiently fulfil my object. When shall I be able to do so myself? My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. I shall not say anything here of my own position nor of the one which interests me still more than mine. I rely upon the bearer of this letter to interpret the feelings of my heart, too withered to express any others but those of the gratitude I owe to MM. Monroe, Skypwith, and Mountflorence for their kindness and their useful endeavours in my behalf. I beg M. Washington will accept the assurance etc.

Noailles Lafayette

The French original can be found here:

“To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 18 April 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-18-02-0041. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 51–54.]

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#american revolution#american history#history#letter#georges de la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1794#1795#george washington#james monroe#founders online#alternative history#felix frestel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vinzenz Georg Kininger (German-Austrian, 1767 - 1851)

The Dream of Eleanor, 1795

#Vinzenz Georg Kininger#the dream of eleanor#1795#18th century art#dreams#nightmares#sleeping#dreaming#nightmare#dream#dark art#gothic art

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boots

1795-1810

Boots began to become fashionable for women in the last quarter of the 18th century, but their use was limited primarily to riding and driving. Few pairs survive, and the peculiar wrap-around leg on this example is specific to this period and extremely rare. Although not well-fitted enough to provide a particularly secure fastening to the foot, the wrapped leg may have been intended to provide superior protection from dust and moisture than the standard laced closure. Colored footwear was a favored means of complimenting plain white dresses in the early 19th century, and the dark teal blue color seen here seems to have been particularly favored.

The MET

#boots#fashion history#historical fashion#accessories#1790s#1800s#europe#regency#regency fashion#1795#1800#1810#blue#lether#18th century#19th century#the met

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Administrators who see armed force as the only remedy for all these movements do not know how to govern. It was a failure to distinguish between sedition and rebellion that led to civil war. I therefore believe I should take no hostile measures against the suddenly arising and partial reactions in the communes of the department of Seine-Inférieure. I am writing to tell the department’s administration to distinguish the instigators, troublemakers, and counter-revolutionaries who always try to take control of these initial popular movements, from the majority of the citizens, who are moved by need or by a moment of giddiness.”

— Napoleon in a letter to Aubert-Dubayet about how to deal with the grain riots, 21 December 1795

Source: Patrice Gueniffey, Bonaparte: 1769–1802

#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#Aubert-Dubayet#Patrice Gueniffey#first french empire#Bonaparte: 1769–1802#letter#quotes by Napoleon#napoleon quotes#19th century#french empire#1790s#1795#history#France#Gueniffey#Bonaparte

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miniature self-portrait of Anne Mee, 1795

From the Victoria & Albert

#anne mee#mee#1795#1790s#1700s#18th century#portrait#painting#art#miniature#self portrait#victoria & albert

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kushi, Kitagawa Utamaro (c.1795). Woodblock print

#art#art history#painting#artists on tumblr#aesthetic#kitagawa utamaro#Utamaro#kushi#woodblock print#japanese woodblock#woodblock art#18th century art#18th century#late 18th century#1795#1790#1790s#late 1700s#1700s art#1700's art#1700s print#1700's print#1700's painting#1700s painting#japan#Japon#japanese#japones#arte#grabado

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Navy Foghorn by Triton from the H.M.S. Caesar, c.1795

Marked with a broad arrow, making this foghorn the property of the Royal Navy and therefore the Admiralty and the King.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

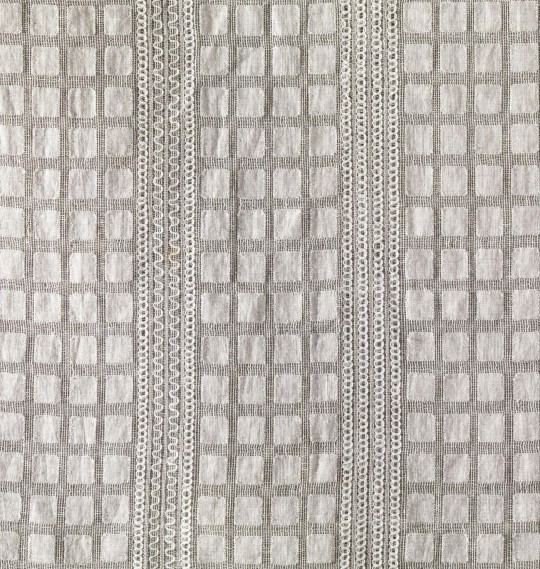

Beige Embroidered Dress, 1795-1799, English.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#beige#embroidery#extant garments#womenswear#dress#1795#1790s#1790s dress#1790s england#1790s britain#english#England#British#Britain#1790s extant garment#V&A

109 notes

·

View notes