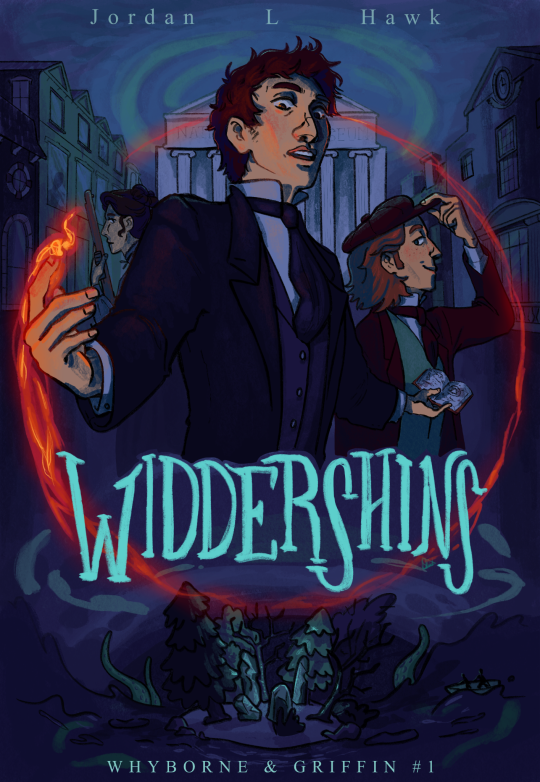

#ALSO the town street in the back? revolutionary for me i almost never draw buildings

Text

Continuing on my quest try more book cover illustration by doing my own take on a cover for Widdershins 🌀

#can you believe ive been chipping away at this for over a year#parts of the lines were drawn a year ago and... i think you can tell lol#but yeah these books mean so much to me#whyborne and griffin#jordan l hawk#widdershins#skiddyscribbles#digital art#my art#fan art#illustration#book cover#cover illustration#percival whyborne#christine putnam#griffin flaherty#queer artist#ALSO the town street in the back? revolutionary for me i almost never draw buildings

167 notes

·

View notes

Link

A black and white portrait of Che Guevara casts a watchful eye over a room adorned with socialist memorabilia from all over the world. A sculpture of two giant marble fists bound by a broken metal chain inscribed with the name “Marinaleda” has pride of place on a grand wooden desk. Behind it sits a small, bearded man wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh scarf and a multicoloured shirt. His name is Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, mayor of the last communist town in Spain.

“Capitalism is like King Midas,” he tells me, “everything it touches turns to gold, commodity, trade and death. I think the capitalist system is necrophilous.”

The 70-year-old has run Marinaleda, near Seville, for almost 40 years, having spent decades fighting the system to create his “utopian” village. Many are starting to question whether this “paradise” will last much longer, after the Socialist PSOE failed to gain an absolute majority in Andalusia’s regional elections in December – for the first time in history. For four decades, Marinaleda has been granted free rein under the Socialists but that would not be guaranteed under a right-wing coalition, which could soon be formed between the Partido Popular, Ciudadanos and far-right party Vox.

Perhaps surprisingly, some 44 people in the town voted for the extreme right party, which won its first ever seats in parliament. But it will probably take more than Vox’s 12 seats to topple Europe’s last communist outpost, which has been a unique success story for decades.

As unemployment stands at 22.9 per cent in Andalusia, only 4 per cent of Marinaleda’s 3,000 citizens are out of work and that is mostly “their choice”. Every civilian is offered a job with the same salary and a house with a mortgage of just €15 (£13.50) a month, while the total cost is deducted if the occupant helps towards building and upkeep.

The town’s success lies in a cooperative where villagers work in the fields or factory to earn €47 for a six-and-a-half-hour working day, bringing in €1,200 a month. Even the unemployed receive €400 from Andalusia’s regional government each month. Although large companies and chains are not permitted, the mayor insists he does not stand in the way of small businesses.

As well as 352 hectares of olive groves, Marinaleda also cultivates broccoli, artichokes, broad beans and peppers, which are jarred at the factory and distributed across the country, creating a year-round harvest.

“The more vegetables we cultivate, the more work we create,” says Sánchez Gordillo. “The money from sales is reinvested into the town to improve the community. It is never for anyone’s personal profit. The land is for anyone who wants it.“

Marinaleda’s journey to utopia began after years of deep repression under General Franco’s harsh fascist regime, when Sánchez Gordillo saw “hunger reach the stomachs of many labourer families” with an unemployment rate of 80 per cent.

Four decades later, El Sindicato de Obreros del Campo (The Union of Farm Workers) was born, leading to the first democratic elections held in Spain – in 1979 – since the collapse of the Republican government. The workers’ collective CUT (Colectivo de Unidad de los Trabajadores) gained an absolute majority in Marinaleda and at the age of 30, Sánchez Gordillo was elected mayor – a position he has upheld ever since.

But “La Lucha” (the fight) would plague the town for another decade as the CUT attempted to take political control over Marinaleda, by staging a 700-strong “hunger strike against hunger”. For more than 90 days Marinaleda villagers occupied the Cortijo de los Humosos, a farmhouse owned by a wealthy duke who left its vast fields uncultivated while families starved. Daily, the Guardia Civil violently expelled them, and daily they returned.

Finally, seven years later, the Andalusian government granted them the land and Marinaleda has never looked back. Now the rustic farmhouse bears the proud words: “This land belongs to all the unemployed labourers of Marinaleda.”

“After all this, we know there is nothing you can’t achieve. Even your wildest dream can become a reality,” says Sánchez Gordillo as we gaze up at a decaying wall painting reading “Tierra Utopia”.

And it is not just local Andalusians who have looked for paradise in this small corner of Spain. Christopher Burke is one of the six British residents living in Marinaleda. The 70-year-old Liverpudlian moved to the town eight years ago with his wife after falling in love with the community spirit during a holiday.

“This place grabs your heart, people are so kind and it’s not about money here,” he says. “It’s great to be part of something that has a different outlook on society and see whether this system is actually achievable. I would say it definitely is.”

He smiles as he tells me how locals regularly pop over with freshly baked bread and recounts stories of the town’s festivals, where even the mayor waits on tables. If it were not for Brexit, Burke says he would never go back to the UK. “If we lose healthcare in Spain I’m absolutely done for because I have glaucoma. It’s a big problem,” he says.

And it seems the town’s folk are also content. As the sweltering sun beats down on us in the lush green fields, young farmer, Alba Martin tells me she has no plans to leave after experiencing life in the outside world.

“The work here is fairer than in other places in Spain,” says the 24-year-old Marinaleda native, speaking from bad experience in Mallorca where she was crippled by her €600-a-month income. “Life is relaxing here, you live well, you’re paid well and above all, things are cheap. The workers are really looked after here.”

Picking broad beans beside her is 42-year-old Antonio Casares, who returned to his native town six years ago after working in construction in Barcelona, Ibiza and others parts of Andalusia. He too worked for a “miserable” salary of €600.

“You can’t live on that,” says Casares, whose wife and teenage daughter work alongside him in the fields. “I had to come back at the beginning of the economic crisis when everything became so expensive. The working days are a lot shorter and life is better here, you feel protected.”

Casares believes in Marinaleda’s model as it has provided almost everyone with a job and he says it’s all thanks to the mayor, who is voted in with an overwhelming majority every year. “If it weren’t for him, we would not have this,” he says gesturing towards Sánchez Gordillo, who is quietly eating freshly picked beans across the field.

It is clear the town’s folk greatly respect the mayor, who was allegedly the subject of multiple assassination attempts by the Guardia Civil for his political protests. He makes time for everyone he bumps into on the street, as they gossip and ask for advice like a close friend. Time, it seems, is not an issue in Marinaleda.

A history teacher until four years ago, Sánchez Gordillo lives on a modest street of small terraced houses. It is well known he has never taken a mayor’s salary and earns the same as everyone else.

“I don’t think anyone is more important than others,” he tells me after asking to be called by his first name as he finds it more “comfortable”.

During the throws of the recession, the revolutionary made international headlines after leading his union to raid supermarkets to provide food for the hungry. Many called him a “Robin Hood”, others a robbing troublemaker.

“The true thief is capitalism,” he insists. “It is a thief of human rights. Europe is the biggest food importer in the world, yet it is throwing its farmers and labourers into bankruptcy.”

And what would he say to people who call him a rebel? “Well I am a rebel,” he responds with a mischievous smile. “Rules are made to be broken.”

Yet when rules are broken in police-free Marinaleda, civilians face nothing more than a stern word from the mayor. “We do not punish anyone. Education is better than repression,” he insists.

However, Burke is concerned some take advantage of the lenient laws of the village.

“Sometimes there’s too much licence for people to do whatever they please,” he says. “Because it has a reputation of having no police, it can attract people buying and selling drugs from other places – like a mini drug market.”

Although Marinaleda is dubbed communist, the mayor describes it as a melting pot of ideologies – socialism, communism and humanism. He draws inspiration from the likes of Gandhi, Lenin, Marx and, of course, Che Guevara. Unlike strict communist models, he believes this watered-down version can work anywhere in the modern world.

“The main objective should be to conserve public property, such as land, housing and energy,” he explains. “There needs to be a direct exchange between the producer and the consumer, with no private business in the middle. If we continue to be ruled by money and by the selfishness and criminality of the global market, we will be on our way to the Third World War.

“The global system right now is just a new type of fascism,” he adds, while admitting that his “utopian” model is difficult to achieve as many don’t like sharing their wealth or possessions.

As the threat of the right looms like a dark cloud over Marinaleda and with elderly Sánchez Gordillo facing recent severe health problems, there is one question many do not want to confront: what will happen when he is no longer there?

“It’s the $64,000 question,” says Burke. “People want it to carry on but he is the central pillar. There’s no obvious successor.”

And it is too early to know if the mayor’s only son, aged seven, will continue his legacy.

Only Sánchez Gordillo is not worried.

“This is a collective effort,” he says simply. “I’m not sure what will happen but I would like the project to be continued for a future of solidarity. And I have faith it will.”

13 notes

·

View notes