#Angelika Hilbeck

Text

"20 Jahre Whistleblower-Preis". Das Buch wurde gestern in Bremen vorgestellt

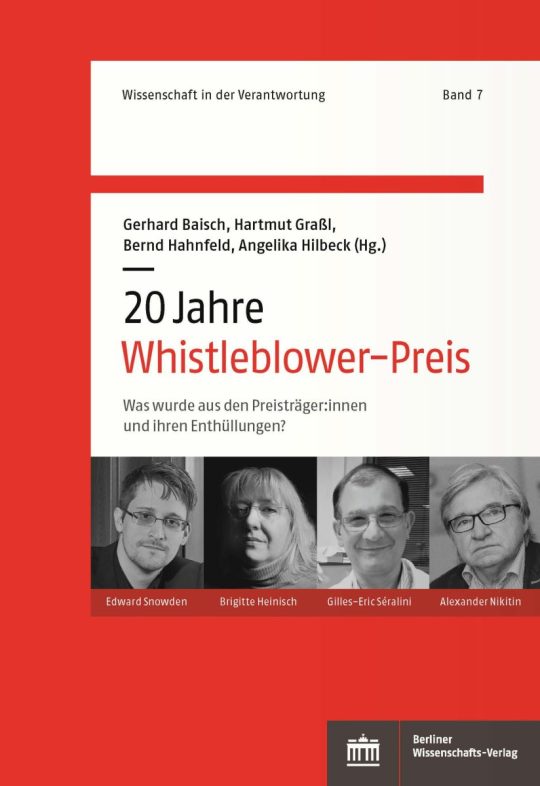

Auf einer Hybridveranstaltung wurde am gestrigen Abend im „Goldenen Saal“ der Villa Ichon in Bremen das Buch „20 Jahre Whistleblower-Preis. Was wurde aus den Preisträger:innen und ihren Enthüllungen?“ (Hrsg. Gerhard Baisch, Hartmut Graßl, Bernd Hahnfeld und Angelika Hilbeck) vorgestellt.

Der Whistleblower-Preis

«Zur Ehrung mutiger WhistleblowerInnen wird seit 1999 alle zwei Jahre der…

View On WordPress

#Angelika Hilbeck#Bremer Friedensforum#Dieter Deiseroth#Gerhard Baisch#Hartmut Graßl#IALANA#neues deutschland#Peter Nowak#VDW#Whistleblowerpreis

0 notes

Link

Sit Down Science Dr. Mercola By Dr. Mercola Industry funded 'science' has tainted our world and turned science based evidence into science biased propaganda. Universities are laundering money through foundations to intentionally hide relationships, while scientists secretly nurture their relationships with corporate executives. Negative outcomes go unpublished, the peer review process is so weak only studies that challenge industry interests are heavily scrutinized (usually by scientists hired by corporate public relations firms). Media is paid handsomely to ensure the public that 'the science is settled', especially when corporate liability is a primary concern. Raw data is held captive, conflicts of interest are not fully disclosed, and studies are designed to specifically obtain a desired outcome. It’s certainly no secret that academic research is often funded by corporations. Academia often claims that such funding allows for innovation and does not influence the outcome of the studies. Industry, too, claims that such relationships do not influence the scientific process. Syngenta spokesman Luke Gibbs even told The New York Times, “Syngenta does not pressure academics to draw conclusions and allows unfettered and independent submission of any papers generated from commissioned research.”1 James Cresswell, Ph.D., a pollination ecology researcher with the University of Exeter in England, had a different take on the matter, however. He spoke openly to the Times about his relationship with the pesticide giant, which included Syngenta-funded research into what’s causing bee colonies to die. Despite having reservations about receiving corporate funding, he did accept it, and soon after began to see the effects of this supposedly independent relationship “The last thing I wanted to do was get in bed with Syngenta,” Cresswell told the Times. “I’m no fan of intensive agriculture [but] … absolutely they influenced what I ended up doing on the project.”2 University Pressured Researchers to Accept Corporate Money Cresswell’s foray into the world of corporate-funded research started when his initial research caused him to question whether neonicotinoid pesticides were to blame for bee deaths. The chemicals, which are produced by Bayer and Syngenta, have been implicated in the decline of bees, particularly in commercially bred species like honeybees and bumblebees (though they’ve been linked to population changes in wild bees as well). In 2012, Syngenta offered to fund further research by Cresswell on the link. It was an offer Cresswell felt he couldn’t refuse. “I was pressured enormously by my university to take that money,” Cresswell told the Times. “It’s like being a traveling salesman and having the best possible sales market and telling your boss, ‘I’m not going to sell there.’ You can’t really do that.”3 A University of Exeter spokesman said up to 15 percent of academic research in Britain is funded by industry and that such sponsors are independently analyzed.4 In Cresswell’s case, he and Syngenta agreed on a study looking into eight potential causes of bee deaths, including a disease called varroosis, which is spread by varroa mites. Pesticide makers have argued that it’s the mites, not pesticides, that are killing bees, but Cresswell’s research didn’t find such a link. Manipulating Research to Fit Industry Agendas When he reported the findings to Syngenta, they pushed back, suggesting he tweak the study in various ways, such as looking at specific loss data in beehives instead of bee stock trends and focusing on data from specific countries or only in Europe, as opposed to worldwide. After the parameters were changed, varroosis became a significant factor in bee colony losses, according to Cresswell’s research. It’s a clear-cut example of how scientific research can be easily manipulated to fit the sponsor’s agenda, a practice that’s well known to occur in pharmaceutical research. In a tongue-in-cheek essay in the British Medical Journal, titled “HARLOT — How to Achieve Positive Results Without Actually Lying to Overcome the Truth,”5 it’s wittily explained exactly how industry insiders can help make their agenda, in this case drugs, look good:6 “Pairing their drug with one that is known to work well. This can hide the fact that a tested medication is weak or ineffective. Truncating a trial. Drugmakers sometimes end a clinical trial when they have reason to believe that it is about to reveal widespread side effects or a lack of effectiveness — or when they see other clues that the trial is going south. Testing in very small groups. Drug-funded researchers also conduct trials that are too small to show differences between competitor drugs. Or they use multiple endpoints, then selectively publish only those that give favorable results, or they 'cherry-pick' positive-sounding results from multicenter trials.” Industry Will Work to Discredit Scientists That Produce Unfavorable Findings Some scientists willingly embrace corporate funding for their research, including James W. Simpkins, a professor at West Virginia University and the director of its Center for Basic and Translational Stroke Research. Simpkins has conducted studies for Syngenta regarding the herbicide atrazine. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) specifically cited research by Tyrone Hayes, Ph. D., an integrative biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, which found atrazine may be chemically castrating male frogs, essentially turning them into female frogs. Hayes used to conduct research for Novartis, which eventually became Syngenta, but he resigned his contractor position after the company refused to allow him to publish the results of studies they had funded. After resigning, he obtained independent funding to repeat the research, which was subsequently published and found that atrazine causes hermaphroditism in frogs. Syngenta attempted to discredit Hayes after the damaging research was released. Meanwhile, Simpkins’ research, which he often co-authors with Syngenta scientists, continues to support atrazine’s supposed safety. In addition to receiving funding for research, Simpkins also receives $250 an hour from Syngenta to consult on expert panels and is involved in a consulting venture with a Syngenta executive, according to the Times, after a Freedom of Information Act request. Syngenta also donated $30,000 to a West Virginia University foundation to support Simpkins’ research.7 How University Foundations Hide Corporate Funds A foundation is a non-governmental entity that is typically established to make grants to institutions or individuals for scientific and other purposes. Donors often give money to foundations instead of to the university itself, in part, because foundations have a fiduciary responsibility to represent the donors’ interest. Also important, money given to a foundation can be kept private in order to protect the donor’s identity and does not become public record.8 It provides the perfect opportunity for industry corporations like Syngenta and others to pay for research on their behalf without receiving any public scrutiny for doing so. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, which is dedicated to improving higher education in North Carolina and the U.S., noted that many researchers refer to foundations as “slush funds” and “shadow corporations” “that too often operate in secrecy, despite spending taxpayers’ money [although foundations are often supported by donations as well].”9 It’s difficult to gain access to university foundations’ activities, contributions and spending. Records are often considered to be off limits, which means corporations can easily channel funds to the universities they believe will give them the best pay-off in the form of favorable research. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal quoted David Cuillier, director of the University of Arizona School of Journalism, as saying:10 “‘I think there are a ton of flags that need to be raised when it comes to university foundations. I think it’s one of the most underreported scams in America. It’s total slush fund … What a great way to hide money for a university.’ [Cuillier] said foundations have allowed universities to hide ‘wrongdoing, and questionable expenditures’ because foundations usually aren’t subject to public records laws, and may not comply with them in states where they are.” Universities and foundations often claim that protecting donors’ privacy is key to keeping fundraising avenues open, but making such information public is in the public’s interest. Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center in Washington, D.C., told the Columbia Journalism Review:11 “Whether donors are buying influence with public agencies is the information that the public needs the most … It’s ironic that the institutions that claim they’ll be unable to raise money if they can’t protect their donors’ privacy will engrave their donors’ names in 10-foot-high letters into the facades of buildings.” Confidentiality Agreements Silence Researchers Another tool used by corporations to control science is confidentiality agreements. Syngenta predecessor Ciba-Geigy had a confidentiality agreement with Switzerland-based agricultural research center Agroscope. So when one of their researchers, Angelika Hilbeck, found problems with genetically engineered corn (specifically that it appeared to be toxic to a beneficial insect, lacewing, which eats other pests), the corporation ordered her to keep the results secret.12 Hilbeck ultimately published the results anyway, and her contract with Agroscope was not renewed. According to the Times:13 “Dr. Hilbeck continued as a university researcher and was succeeded at Agroscope by Jörg Romeis, a scientist who had worked at Bayer and has since co-authored research with employees from Syngenta, DuPont and other companies. He has spent much of his career trying to debunk Dr. Hilbeck’s work [and has since become the leader of Agroscope’s biosafety research group].” US Biotechnology Panel Financially Tied to Biotech Industry Even government panels are not immune from industry ties. In fact, they’re prime targets for conflicts of interest. The latest scandal involves a panel studying biotechnology, which is expected to give advice to The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, which in turn provides policy guidance to the U.S. government. Of the 13 experts named to the panel, seven have potential conflicts of interest. This includes:14 Richard M. Amasino, professor of biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who holds various biotechnology patents Jeffrey Wolt, professor of agronomy and toxicology at Iowa State University, who has a commercial interest that violates the organization’s conflict of interest policy Steven P. Bradbury, professor of environmental toxicology at Iowa State University, who owns a consulting firm that advises companies on biotechnology Richard Murray, professor of bioengineering at the California Institute of Technology, who co-founded Synvitrobio, a synthetic biology (i.e., genetic engineering) start-up Steven L. Evans, fellow in seeds discovery research and development at Dow AgroSciences, which has major interests in the biotechnology industry Dietary Rules Influenced by Corporate-Funded Research The tentacles of industry-funded research reach far and wide — even to your dinner table. In investigative journalist Gary Taubes’ new book, “The Case Against Sugar,” you can read how food companies manipulated research to make sugar a mainstay of Americans’ diets. As it became increasingly clear that excess sugar was linked to rising rates of obesity, diabetes and other chronic diseases, the Sugar Association, an industry trade group, stepped in to combat it by funding industry-friendly research and attacking the credibility of researchers that found otherwise. Decades’ worth of research convincingly shows excess sugar damages your health, yet the sugar industry managed bury the evidence and cover it up with faux science that supports sugar as an important food. According to The Wall Street Journal:15 “These efforts were successful enough to influence the language of FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] reports on sugar in 1977 and 1986, as well as the first government-compiled Dietary Guidelines, released in 1980, which unsurprisingly declared that fat caused disease.” While scientific research is far from, well, an exact science, when industry funding is involved it may be virtually impossible for scientific truth to be heard. Whether the subject is sugar, pesticides or biotechnology is irrelevant. Although most researchers and sponsoring companies will insist the research is sound and unbiased, it’s well-known that industry-funded research almost always favors industry.

0 notes

Text

Scientists Loved and Loathed by an Agrochemical Giant

What would you do if you were a university researcher who signed a confidentiality agreement with a company as part of a consulting contract to not discuss sensitive research, and your findings turn out to be contrary to what the company had hoped you would find out: (1) maintain confidentiality or (2) find some way to share your findings with the public? Why? What are the ethics underlying your decision?

The bee findings were not what Syngenta expected to hear.

The pesticide giant had commissioned James Cresswell, an expert in flowers and bees at the University of Exeter in England, to study why many of the world’s bee colonies were dying. Companies like Syngenta have long blamed a tiny bug called a varroa mite, rather than their own pesticides, for the bee decline.

Dr. Cresswell has also been skeptical of concerns raised about those pesticides, and even the extent of bee deaths. But his initial research in 2012 undercut concerns about varroa mites as well. So the company, based in Switzerland, began pressing him to consider new data and a different approach.

Looking back at his interactions with the company, Dr. Cresswell said in a recent interview that “Syngenta clearly has got an agenda.” In an email, he summed up that agenda: “It’s the varroa, stupid.”

For Dr. Cresswell, 54, the foray into corporate-backed research threw him into personal crisis. Some of his colleagues ostracized him. He found his principles tested. Even his wife and children had their doubts.

“They couldn’t believe I took the money,” he said of his family. “They imagined there was going to be an awful lot of pressure and thought I sold out.”

The corporate use of academia has been documented in fields like soft drinks and pharmaceuticals. But it is rare for an academic to provide an insider’s view of the relationships being forged with corporations, and the expectations that accompany them.

A review of Syngenta’s strategy shows that Dr. Cresswell’s experience fits in with practices used by American competitors like Monsanto and across the agrochemical industry. Scientists deliver outcomes favorable to companies, while university research departments court corporate support. Universities and regulators sacrifice full autonomy by signing confidentiality agreements. And academics sometimes double as paid consultants.

In Britain, Syngenta has built a network of academics and regulators, even recruiting the leading government scientist on the bee issue. In the United States, Syngenta pays academics like James W. Simpkins of West Virginia University, whose work has helped validate the safety of its products. Not only has Dr. Simpkins’s research been funded by Syngenta, he is also a $250-an-hour consultant for the company. And he teamed up with a Syngenta executive in a consulting venture, emails obtained by The New York Times show.

Dr. Simpkins did not comment. A spokesman for West Virginia University said his consulting work “was based on his 42 years of experience with reproductive neuroendocrinology.”

Scientists who cross agrochemical companies can find themselves at odds with the industry for years. One such scientist is Angelika Hilbeck, a researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. The industry has long since challenged her research, and she has been outspoken in challenging them back.

Going back to the 1990s, her research has found that genetically modified corn — intended to kill bugs that eat the plant — could harm beneficial insects as well. Back then, Syngenta had not yet been formed, but she said one of its predecessor companies, Ciba-Geigy, tried to stifle her research by citing a confidentiality agreement signed by her employer then, a Swiss government research center called Agroscope.

Confidentiality agreements have become routine. The United States Department of Agriculture turned over 43 confidentiality agreements reached with Syngenta, Bayer and Monsanto since the beginning of 2010 after a Freedom of Information Act request. Agroscope turned over an additional five with Swiss agrochemical companies.

Many of the agreements highlight how regulators are often more like collaborators than watchdogs, exploring joint research and patent deals that they agree to keep secret.

One agreement between the U.S.D.A. and Syngenta, which came with a five-year nondisclosure term, covered things including “research and development activities,” “manufacturing processes” and “financial and marketing information related to crop protection and seed technologies.” In another agreement, a government scientist was barred even from disclosing sensitive information she heard at a symposium run by Monsanto.

The Agriculture Department, in a statement, said that without such agreements and partnerships, “many technological solutions would not make it to the public,” adding that research findings were released “objectively without inappropriate influence from internal or external partners.”

Luke Gibbs, a spokesman for Syngenta, which is now being acquired by the China National Chemical Corporation, said in a statement, “We are proud of the collaborations and partnerships we have built.”

“All researchers we partner with are free to express their views publicly in regard to our products and approaches,” he said. “Syngenta does not pressure academics to draw conclusions and allows unfettered and independent submission of any papers generated from commissioned research.”

A look at the experiences of the three scientists — Dr. Cresswell, Dr. Simpkins and Dr. Hilbeck — reveals the ways agrochemical companies shape scientific thought.

A Reluctant Partner

For James Cresswell, taking money from Syngenta was not an easy decision.

Dr. Cresswell has been a researcher at the University of Exeter, in England’s southwest, for a quarter-century, mostly exploring the esoterica of flower reproduction in papers with titles like “Conifer ovulate cones accumulate pollen principally by simple impaction.” He was not used to making headlines.

But about a half-decade ago, he became interested in the debate over neonicotinoids, a class of pesticide derived from nicotine, and their effects on bee health. Many studies linked the chemicals to a mysterious collapse of bee colonies that was in the news. Other studies, many backed by industry, pointed to the varroa mite, and some saw both factors at play.

Dr. Cresswell’s initial research led him to believe that concerns about the pesticides were overblown. In 2012, Syngenta offered to fund further research.

While many academics resisted efforts by The Times to examine their communications with Syngenta, Dr. Cresswell did not challenge a records request submitted to his university. And he spoke with candor.

LONG ARTICLE CONTINUES

0 notes

Video

youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWfmD-7mKhc

The Use of Genetically Modified Organisms in Food - The 2015 Arthur N. Rupe Debate

1 28 min 53 sec

Angelika Hilbeck and Pamela C. Ronald at University of California Santa Barbara on May 29, 2015.

2 notes

·

View notes