#Anissa M. Bouziane

Text

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 (@AnissaBouziane), author of DUNE SONG

Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 was born in Tennessee, the daughter of a Moroccan father and a French mother. She grew up in Morocco, but returned to the United States to attend Wellesley College, and went on to earn an MFA in fiction writing from Columbia University and a Certificate in Film from NYU. Currently, Anissa works and teaches in Paris, as she works to finish a PhD in Creative Writing at The University of Warwick in the UK. Dune Song is her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter: @AnissaBouziane.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10 (who also got her MFA in writing from Columbia, albeit in creative nonfiction), had the chance to chat with Anissa via email about Dune Song, doing research, publishing in translation, forming a writing community, and catching up on reading while in quarantine. E.B. is especially grateful to Anissa for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series while we are in the middle of a global pandemic.

And if you like the interview and want to hear more from Anissa, you can attend her virtual talk at The American Library tomorrow (Tuesday, May 26, 2020) at 17h00 (Central European Time). RSVP here.

EB: First, thank you for being part of this series! I loved getting to read Dune Song, especially right now with everything going on. I loved getting to escape into Jeehan’s worlds, though sort of depressing to think of post-9/11-NYC as a “simpler time” to escape to. My first question is: Reading your biography, I know that you, much like Jeehan, have moved back and forth between the United States and Morocco––born in the U.S.A., grew up in Morocco, and then back to the U.S.A. for college. You’ve also mentioned elsewhere that this book was rooted in your own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. How much of your own life story inspired Dune Song?

AMB: Indeed, Dune Song is rooted in my own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. As a New Yorker, who experienced the tragedy of that now infamous Tuesday in September almost 19 years ago, I would not have chosen the collapse of the World Trade Center as the inciting incident of my novel had I not lived through those events myself. So yes, much of what Jeehan, Dune Song’s protagonist, goes through in NYC is rooted in my own life experience. Nonetheless the book is not an autobiography — I would consider it more of an auto-fiction, that is a fiction with deep roots in the author’s experience. The New York passages speak of the difficulties of coming to terms with the tragedy that was 9/11 — out of principle, I would not have chosen 9/11 as the inciting incident of my novel if I did not have first hand experience of the trauma which I recount.

EB: Thanks for saying that. I feel like there is a whole genre of 9/11 novels out there now and a lot of them make me uncomfortable because it feels like they are exploiting a tragedy. Dune Song did not feel that way to me. It felt genuine, like it was written by someone who had lived through it.

AMB: As for the desert passage that take place in Morocco, though I am extremely familiar with the Moroccan desert — and have traveled extensively from the dunes of Merzouga to the oasis of Zagora — this portion of the novel is totally fictional. That being said, I am one of those writers who rides the line between fiction and reality very closely, so if you ask me if I ever let myself be buried up to my neck in a dune, the answer would be: yes.

EB: How did the rest of the story come about? When and how did you decide to contrast the stories of the aftermath of 9/11 with human trafficking in the Moroccan desert?

AMB: Less than six months after 9/11, in March of 2002 I was invited back to Morocco by the Al Akhawayn University, an international university in the Atlas Mountains near the city of Fez. There I gave a talk which would ultimately provide me with the core of Dune Song: the chapter that takes place in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, where following a mass in commemoration of the victims of the 9/11 attacks, an Imam from a Mosque in Queens was asked to recite a few verses from the Holy Quran. The Moroccan artists and academics present that day were deeply moved by my talk (which in fact simply recounted my lived experience); they told me that I should turn my talk into a novel. I thought the idea interesting and began to write, but within a year the Iraq War was launched and suddenly a story promoting dialogue and mutual understanding between the Islamic World and the West seemed to interest few, so I moved on to other things. Nonetheless, the core of Dune Song stayed with me.

Years later, as I re-examined that early draft, I realized that if I was to turn it into a novel, it had to transcend my life experience — and that is when I turned to my knowledge of the Moroccan desert and my longstanding interest in illegal trafficking across the Sahara desert. I returned to Morocco from the USA in 2003 thanks to Wellesley’s Mary Elvira Stevens Alumnae Traveling Fellowship to research what will soon be my second novel, but truth be told I got the grant on my second try. My first try in the mid-90s had been a proposal to explore the phenomenon of South-North migration across the Sahara and the Mediterranean. I remained an active observer of issues around Trans-Saharan migration, but I went to the desert three or four times on my return to Morocco before I understood that this was where Jeehan too must travel. My decision to bring Jeehan there probably emanated out of the serenity that I experienced when in the desert, but if Dune Song was to be more than just a cathartic work, I realized it should also attempt to draw a cartography of a better tomorrow — and so Jeehan would have to go to battle for others whose fate was in jeopardy because of a continued injustice overlooked by many. It seemed clear to me that Jeehan’s path and those of the victims of human trafficking had to cross. Her quest for meaning in the wake of the 9/11’s senseless loss of life depended on it.

EB: I really loved the structure of the book––the braided narratives, moving back and forth between New York and Morocco. How did you decide on this structure? And how and why did you choose to have the Morocco chapters move forward chronologically, while the New York chapters bounce around in time? To me it felt reflective of the way that we try to make sense of a traumatic event––rethinking and obsessing over small details, trying to make sense of chaos, all the pieces slowing coming together.

AMB: Fragmented narratives have always been my thing, probably because, as someone who straddles many cultures and who feels rooted in many geographies, I felt early on that fragmented forms leant themselves to the multi-layered stories that emanated out of me. My MFA thesis was an as-yet-unpublished novel entitled: Fragments from a Transparent Page (inspired by Jean Genet’s posthumous novel). Even my early work in experimental cinema was obsessed with fragmentation — in large part because I believe that though we experience life through the linear chronology of time, we remember our lives in far-less linear fashion. I agree with you that trauma further disrupts our attempts at streamlining memory. The manner in which we remember, and how the act of remembering — or forgetting — shapes the very content of our memory is essential to my work as a novelist, for I believe it is essential to our act of making meaning of our lived experience.

In Dune Song the reader watches Jeehan travel deep into the Moroccan desert. We also watch her remember what has come before. And we witness her struggle with her memories, which is why the New York chapters bounce around in time. The thing she is frightened of most — her memories of seeing the Towers crumble, knowing countless souls are being lost before her eyes — this she cannot remember, or refuses to remember clearly. And it is not until she is in the heart of the desert and is confronted with the images of the collapse of the WTC as beamed through a small TV screen in Fatima’s kitchen, that she takes the reader with her into the recollection of that trauma. Once that remembering is done, her healing can truly begin — and the time of the novel heads in a more chronological direction.

EB: While this is a work of fiction, I imagine that a significant amount of research went into writing this book, especially concerning the horrors of human trafficking. What sorts of research did you do for Dune Song?

AMB: As I mentioned earlier, beginning in the mid-nineties, the issue of human trafficking across the Sarah became a subject of academic and moral concern to me. But the fact that I grew up in Morocco, and spent many of my summers in my paternal grandmother’s house in Tangier, sensitized me to this topic very early on. Tangier, is located at the most northern-western tip of the African continent, and therefore it is a weigh station for many who aim to cross the Straits of Gibraltar with hopes of getting to Spain, to Europe. I recall a moment when as a teenager I gazed out over the Straits from the cliff of Café Hafa, where Paul Bowles used to write, and imagined that the body of water before me as a watery Berlin Wall. One of my unpublished screenplays, entitled Tangier, focused on the tragedy of those who risked their lives to cross the Straits. So, did I do research to write Dune Song? You bet — I folded into Dune Song topics that had been in the forefront of my consciousness for years.

EB: I know that Dune Song has been published in Morocco by Les Editions Le Fennec, published in the United Kingdom by Sandstone Press, published in France by Les Editions du Mauconduit, and published in the U.S.A. by Interlink Books. What was the experience like, having your book published in different languages and in different countries? Were any changes made to the novel between editions?

AMB: Dune Song was first published in Morocco in an early French translation. Initially this was out of desperation, not choice. I wrote Dune Song in English, and I shopped the English manuscript in the UK and the US to no avail. I was told by people who mattered in literary circles that the book was too transgressive to be published in either the US or UK markets. Suggestion was made to me that I remove all the New York passages from the book if I was to stand a chance of having it hit the English speaking market. I refused to do so and instead worked with my friend and translator, Laurence Larsen to come up with a French version. That being done, I shopped it around in France only to be told that a translation couldn’t be published before the original. Dismissively, I was told to seek-out who might benefit from an author like me existing. The comment hit me like a slap across the face, and I sincerely thought of giving up on the work all together — more than that, I thought I might give up on writing — but my students (who have always been a source of support for me — more on that later) convinced me not to trow in the towel. Once I had the courage to re-examine the question posed to me by the French, I realized that there was a viable answer: the Moroccans. That’s when I contacted Layla Chaouni, celebrated French-language publisher in Casablanca, and asked her if she might want to consider Dune Song for Le Fennec.

Layla’s enthusiasm for the novel marked a huge shift in Dune Song’s fortunes: the book was published in Morocco, won the Special Jury Prize for the Prix Sofitel Tour Blanche, was selected to represent Morocco at the Paris Book fair in 2017, which then lead me (through my Wellesley connections) to gain representation by famed New York literary agent Claire Roberts. It was Claire who got me a contract with Sandstone as well as with Interlink and with Mauconduit — she has been an unconditional champion of my work, and for this I will be eternally grateful. It must be noted that when the book got to Sandstone, I believe it was ‘wounded’ — it had gone through many incarnations, but I was not thrilled with the final outcome. My editor at Sandstone, the fantastic Moria Forsyth gave me the space and guidance to “heal” the manuscript — that is, she identified what was not working and sent me off to fix things, with the promise of publication as a reward for this one last push. The result was the English version that everyone is reading today (published in the UK by Sandstone and in the US by Interlink Publishing). My translator, Laurence Larsen worked diligently to upgrade the French translation for Mauconduit.

It has been a long journey, at times dispiriting, at time exhilarating. I am terribly excited that today, my Dune Song has been published in four countries, and there is hope for more. In the darkest hours of the process, I gave myself permission to give up. “You’ve come to the end of the line,” I told myself, “it’s okay if your stop writing altogether.” In hindsight, hitting rock bottom was essential, because the answer that came back to me was NO. No, I won’t stop writing. I accepted that I might never be published, but I refused to stop writing, for to do so would be to give up on the one action that brought meaning to my life.

EB: You’ve mentioned that Dune Song was originally written in English, though I am guessing, based on your background and reading the book, that you also speak Arabic and French. How and why did you decide to write Dune Song in English? And did you translate the work yourself into the French edition?

AMB: Yes, Dune Song was originally written in English. Though I speak French and Moroccan Arabic (Darija) fluently, my imagination has always constructed itself in English. Growing up in Morocco as of the age of eight, I considered English to be my secret garden — the material of which my invented worlds were made. I had often thought that my return to the United States, at the age of 18 to attend Wellesley, was an attempt to find a home for my words. Even today, living in Paris, I continue to write in English.

I chose not to translate Dune Song into French myself, primarily because my French does not resemble my English — it exists in a different sphere belonging more to the spoken word. I wanted a translator to show me what my literary voice might sound like in French. I have done a fair amount of literary translation, but always from French into English, and not the other way around. Nonetheless, as you rightly noted, I have actively wanted to give my readers the illusion of hearing Arabic and French when reading Dune Song. I like to refer to this as creating Linguistic Polyphony: were the base language (in this case English) is made to sing in different cords. I think my French translator, Laurence Larsen was able to reverse this process and give the French text the illusion of hearing English and Arabic.

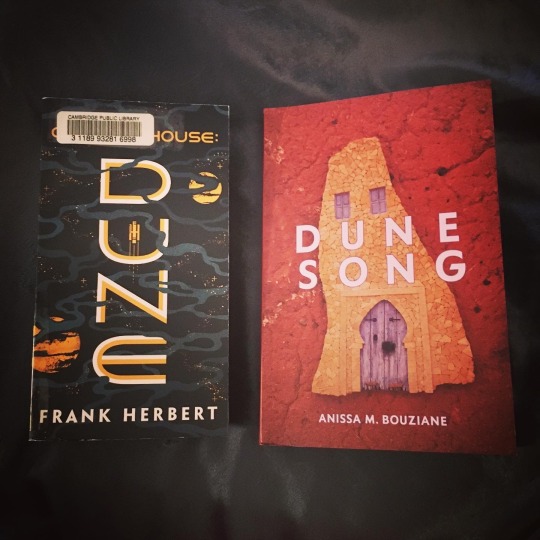

EB: In addition to your research, what other books influenced or inspired Dune Song? My fiancé, Richie, happened to be reading the Dune chronicles by Frank Herbert while I was reading your book, and then I laughed to myself when I saw you reference them on page 56.

AMB: The Dune Chronicles, of course! Picture this: a teenage me reading Frank Herbert’s Dune while waiting at the Odaïa Café on the old pirate ramparts of Rabat while my mother was shopping in the medina. I read twelve volumes of the Chronicles. Reading voraciously in English while growing up in Morocco was one of the ways for me to always ensure that my imagination was powering up in English. You’ll note that I give Jeehan this same passion for books. Many of the books that she turns to in her time of need are the books that have shaped who I am and how I see the world: Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Allende’s House of Spirits, Okri’s The Famished Road, Calvino’s The Colven Vicount, Aristotle’s The Poetics, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry…

EB: What are you currently reading, and/or what have you read recently that you’ve really enjoyed? What would you recommend we all read while laying low in quarantine?

AMB: I’m one of those people who reads many books (fiction, non-fiction, and poetry) at the same time. If I look at my night stand right now, here are the titles I see: in English — Hannah Assadi’s Sonora, Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, Du Pontes Peebles’ The Air You Breathe, and Margo Berdeshevsky’s poetry collection: Before the Drought, in French — Santiago Amigorena’s Le Ghetto intérieur, and Mahi Binebine’s La Rue du pardon.

In quarantine, Margo’s poetry has provided me with a level of stillness and insight I did not realize I longed for — and has seemed prescient in its understanding of humanity’s relationship to our planet.

EB: On your website, you mention you are also a filmmaker, an artist, and an educator in addition to being a writer. How do you think working in those other fields/mediums influences your writing? How do you think being a writer influences those other pursuits?

AMB: Writing as an act of meaning making is the mantra I constantly recite to my students. In my moment of greatest despair, they echoed it back to me. Why do I allow myself this type of discourse with my students? Because as a high school teacher of English and Literature, my speciality is the teaching of writing. While at Columbia University, though enrolled in a Masters of Fine Arts in Fiction at the School of the Arts, I had a fellowship at Columbia Teachers College, specifically with The Writing Project lead by Lucy Calkins (today known as The Reading and Writing Project). There I worked as a staff developer in the NYC Public School system and conducted research that contributed to Lucy’s seminal text, The Art of Teaching Writing. Over the years my students have helped me realize why we bother to tell stories and how elemental writing is to our very humanity. I could never divorce my writing from the act of teaching.

Regarding cinema, as I mentioned earlier, my frustration with how to translate multi-lingual texts into one language is what originally drove me to experiment with film. What I discovered as I dove deeper into the medium, was how key images are to the act of storytelling. Once I returned to writing literature, I retained this awareness of the centrality images in the transmission of lived experience. I smile when readers of Dune Song point out how cinematic my writing is — film and fiction should not stand in opposition one to the other.

EB: Writing a book takes a really long time and can be a really lonely and frustrating experience. Who did you rely on for support during the process? Other writers? Family? Friends? Fellow Wellesley grads? What does your writing/artistic community look like?

AMB: It took me over ten years to write and publish Dune Song. The tale of how it came to be is almost worthy of a novel itself. When things were at their most arduous, I went back to reading Tillie Olsen’s Silences, about how challenging it is for women to write and publish — it was a book I had been asked to read the summer before my Freshman year. Though I won’t tell the full story here — I must acknowledge that without the support of my sister, Yasmina, and my parents, as well as essential and amazing women in my life, many of them from Wellesley, Dune Song would never have seen the light of day. Sally Katz ‘78, has been my fairy-godmother, all good things come to me from her, plus other members of the astounding Wellesley Club of France, especially its current president, my dear classmate, Pamela Boulet ‘87. I must thank my earliest Wellesley friend, Piya Chatterjee ’87, who plowed through voluminous and flawed drafts. Karen E. Smith ’87, who reminded me of my creative abilities when I seemed to have forgotten, and who brought her daughter to my London book launch. Dawn Norfleet ’87 who collaborated with me on my film work when we were both at Columbia, and Rebecca Gregory ’87, with who was first in line to buy Dune Song at WH Smith Rue de Rivoli, and Kimberly Dozier ’87, who raised a glass of champagne with me in Casablanca when the book first came back from the printers. The list of those who helped me get this far and who continue to help me as I forge ahead is long - and for this I am grateful… writing is a thrilling but difficult endeavor, and without community and friendship, it becomes harder.

And since the book has been published, the Wellesley community has been there for me in ways big and small, even in this time of COVID. Out in Los Angeles, Judy Lee ’87 inspired her fellow alums to read Dune Song by raffling a copy off a year ago — and now, they have invited me to speak to their club on a Zoom get-together in June!

EB: Speaking of Wellesley, and since this is an interview for Wellesley Underground, were there any Wellesley professors or staff or courses that were particularly formative to you as a writer? Anyone you want to shout out here?

AMB: When a student at Wellesley, a number of Professors where particularly supportive of me and my work. At the time, I was a Political Science and Anthropology major; Linda Miller and Lois Wasserspring of the Poli-Sci department were influential and present even long after I graduated, and Sally Merri and Anne Marie Shimony of the Anthropology department helped shape the way I see the world.

Any mention of my early Wellesley influences must include Sylvia Heistand, at Salter International Center, and my Wellesley host-mother, Helen O’Connor — who still stands in for my mother when needed!

More recently, Selwyn Cudjoe and the entire Africana Studies Department, have become champions of my work. Thanks to their enthusiasm for Dune Song, I was able to present the novel at Harambee House last October and engage in dialogue about my work with current Wellesley students and faculty. This was a remarkable experience which gave me a beautiful sense of closure regarding the ten-year project that has been Dune Song. Merci Selwyn!

I speak of closure, but my Dune Song journey continues, just before the pandemic, thanks to the Wellesley Club of France and Laura Adamczyk ’87, I was able to meet President Johnson and give her a copy of Dune Song!

EB: Is there anything else you’d like the Wellesley community to know about Dune Song, your other projects, or you in general?

AMB: Way back at the start of the millennium, when the Wellesley awarded me the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship, I set out to excavate family secrets and explore the non-verbal ways in which generation upon generation of mothers transmit traumatic memories to their daughters. My research took me many more years than expected, but I am now in the process of writing that novel, along with a doctoral thesis on Trauma and Memory.

In conjunction with this second novel, I am working with Rebecca Gregory ’87, to produce a large-scale installation piece exploring the manner in which the stories of women’s lives are measured and told.

EB: Thank you for being part of Wellesley Writes It!

#wellesley writes it#wellesleywritesit#Anissa M. Bouziane#Anissa Bouziane#class of 1987#EB Bartels#E.B. Bartels#class of 2020#wellesley#wellesley college#Dune Song#France#Morocco#New York#USA#book#books#novel#novels#wellesley '87#wellesley '10

1 note

·

View note