#Black Student Union

Text

Misti Tope is the current head principal of Classen School of Advanced Studies at North East High School in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Misti Tope has been fostering an environment of fear & hostility among everyone including students, faculty, educators & parents. It is to the point where parents are organizing private meetups to discuss her. Students are creating petitions.

Misti Tope has recently stated multiple times to students & faculty that she wants to create an educational environment that aligns with Ryan Walters views.

Misti Tope has been firing teachers of color & working to force them out. Misti Tope recently fired a trans teacher, Mx Mustain, who was close to receiving tenure. Misti Tope, of course, lied about the reason behind these firings.

Misti Tope has threatened female students who wanted to report predatory behavior from faculty. She went so far as to make threatening phone calls & disbanded an after school club over these students compiling information. Misti Tope has threatened to disband any club that seeks to protect themselves from predatory teachers.

Misti Tope physically gropes students over dress code violations. Whether they are violating dress code or not, this is unexcusable. Misti Tope also makes derogatory commentary on female students being "busty" & "curvy".

Misti Tope actively intimidates the female student body. There have been situations where male students have shown their penises to female students & all the male students receive is detention. Misti Tope has called female students "overemotional" & "dramatic".

Misti Tope keeps seeking ways to disband the Black Student Union. Misti Tope has vocally compared black students in BSU more than once to rats & roaches pulling at each other's weaves. Misti Tope also stated that black students are equivalent to goldfish & don't deserve an education because they are incapable of retaining information.

Misti Tope is an active Holocaust denier. The son of a Holocaust survivor was kicked off stage while giving a presentation. Misti Tope shuts conversations surrounding the Holocaust.

Misti Tope's son who is a student is known to carve & graffiti swastikas & other Nazi imagery all over the school. Misti Tope's son also states antisemitic, homophobic, transphobic & racist rhetoric. Misti Tope scapegoats by saying he learns this from anime, which is untrue. Misti Tope also allows her son to skip classes & wander around the school.

Misti Tope attempts to force transgender students to use restrooms of their biological gender. Misti Tope has told transgender students to dress according to their biological gender.

Misti Tope is seeking to end funding to the athletic departments & divert funds to a swim team.

Misti Tope is not the future of Classen. Misti Tope is unfit to be a part of any school district in any capacity.

Again, I am not the only parent. Other parents are organizing & mobilizing of their own accord & having meetups. The same is being said of students. I have added screenshots because the admins of the Classen Parent group like deleting posts as evidence when things become heated.

Students, though this action was not right, cornered Misti Tope in her office this Friday (05/03/24). This is how threatened they feel by Misti Tope, this is the environment she's creating.

#Oklahoma#Oklahoma City#Oklahoma City Public Schools#OKCPS#Classen School of Advanced Studies at North East High School#Misti Tope#racist#homophobic#transphobic#antisemitism#antisemitic#teachblr#student#teacher#educator#faculty#Black Student Union#BLM#Gay Straight Alliance#LGBTQIIA+#Holocaust#education#advocacy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alabama anti-DEI law shuts Black Student Union office, queer resource center at flagship university

the Black Student Union announced that the group would no longer have a designated place on campus, in compliance with recent statewide legislation that prohibits public universities and state agencies from allocating resources to diversity equity and inclusion programs … a queer resource center called Safe Zone was also shuttered …

Both the Queer Student Association and the Black Student Union have been forced to scramble for other funding for programming, especially as the groups try to help freshman get oriented, according to their respective presidents.

Alabama Bigot Gov. Kay Ivey, in a statement released when she signed the bill in March 2024:

“My administration has and will continue to value Alabama’s rich diversity, however, I refuse to allow a few bad actors on college campuses – or wherever else for that matter – to go under the acronym of DEI, using taxpayer funds, to push their liberal political movement counter to what the majority of Alabamians believe.”

#university of alabama#racism#homophobia#black student union#queer student association#education#lgbtq#lgbt#queer#crt#dei#alabama#2024#2020s

0 notes

Text

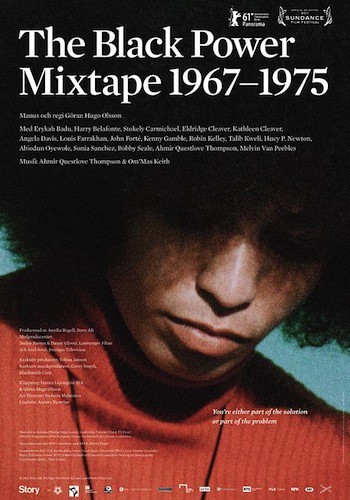

Black History Month 2024 at New College

Annual celebrations of Black History Month (BHM) at New College bring a variety of events as a way for students, staff and faculty to honor the heritage and ongoing influence of Black history and culture in the United States. This February the New College community has the opportunity to recognize and honor an integral part of American life through movie screenings, a poetry workshop, eating…

View On WordPress

#black history#black history month#Black Student Union#crafty cookout#feminist fridays#sauce#student activities and campus engagement

0 notes

Text

every black kid in a school with a Black Student Union should join it

BSU is great and very beneficial, especially in PWIs

favorite thing at school by far

1 note

·

View note

Text

by Dion J. Pierre

The University of Michigan’s Black Student Union (BSU) has resigned from the anti-Zionist student group Tahrir Coalition, citing “pervasive” anti-Black discrimination fostered by its mostly Arab and Middle Eastern leadership.

“Black identities, voices, and bodies are not valued in this coalition, and thus we must remove ourselves,” BSU said in a statement posted on Instagram. “The anti-Blackness within the coalition has been too pervasive to overcome, and we refuse to endure it.”

Proclaiming its continued support for the anti-Zionist movement, the group continued, “The BSU’s solidarity with the Palestinian people is unwavering, but the integrity of the Tahrir Coalition is deeply questionable. We refuse to subject ourselves and our community to the rampant anti-Blackness that festers within it. For this reason, we will no longer be a part of the Tahrir Coalition.”

BSU did not cite specific examples of the racism to which Black students were allegedly subjected, but its public denouncement of a group which has become the face of the pro-Hamas movement at the University of Michigan is significant given the history of cooperation between BSU and anti-Zionist groups on college campuses across the US.

BSU’s Black members are not, however, the first to openly clash with anti-Zionist Arabs.

When Arab and Palestinian anti-Zionist activists launched a barrage of racist attacks against African Americans on social media in August, Black TikTok influencers descended on the platform in droves to denounce the comments, with several announcing that they intended not only to remove Gaza-related content from their profiles but also to cease engaging in anti-Zionist activity entirely. The conversation escalated in subsequent posts, touching on the continuance of Black slavery in the Arab world and what young woman called “voracious racism” against African Americans.

“What’s even crazier is that earlier people were like, oh these are bots, no — this is how people really feel. And she made a video that’s a real human being that feels exactly that way,” one African American woman said. “These are people who feel like they are entitled to the support of Black people no matter what, that they get to push us around and tell us who the hell we get to vote for if we support them … They’ve lost their minds.”

An African American male said, “Why don’t we talk about the Arab slave trade? And keep in mind that the Arabs have enslaved more Black people than the Europeans combined.” Another African American woman accused Arabs of not denouncing slavery in Antebellum America.

#university of michigan#university of michigan's black student union#racist attacks#racist attacks against african americans#anti-zionists#arab anti-zionists#palestinian anti-zionists#tahrir coalition

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

i know for legal reasons black student unions cant prevent nonblack people from joining, but why would you as a nb person want to join a bsu in the first place? reminds me of the nonblack people who kept asking to join my black writers server so they could "observe" or "better understand black experiences" like um. time and place!!

#it just confuses me like. not that nonblack students cant interact with black students at awll but you can just like. fund the bsu#and support any fundraisers they do.#like i personally feel no inclination to join student unions of marginalized groups im not a part of because there are better ways to#learn about their groups that dont involve like. invading their personal spaces intended specifically to uplift and support them

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need to write about how that school district was also on some weird cultural xtian shit in addition to the covert (and overt) racism bc like, i went to actual xtian school b4 i moved to this state and did k-12 in public school that was supposed to be secular ... like obv i get how baked in certain things are w like almost every us public school (major breaks scheduled around xmas easter etc) but it was also things like teachers firmly chiding kids for saying 'oh my god' every minute and it would drive me nuts ... this was well before i even started questioning my views on faith. on a base level i would think 1) that's not what 'taking the lord's name in vain' means and 2) this isn't even a xtian school. i went to xtian school. why do you care what anyone is saying as long as they're not actually cussing??

#ooooh when i finally move away from this area i can tell the juicy juicy stuff about the town i grew up in and its relation to racism#like why were we singing/playing hymns in music class/band/choir etc and all this . did the music curriculum really require the explicitly#religious music?#and back on the racism tip i remember when they first created the black student union at my high school as i was graduating it was a whole#controversy over it. and i remember my junior year these kids did blackface to do a cool runnings cosplay for halloween. etc etc#insanity luvs#it was sooooo much internalized self hate and shame i had to unlearn lmao

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture it: sophomore American history. The year is two thousand and eight. The teacher is known for passing out jolly ranchers, one per student per day, when a kid does a good job. One day, she wants us to list every state in the country. Kids start listing them off in unison, mostly alphabetically, but falter around the I states (this is in Indiana, mind). Except one triumphant voice lingers as every other voice trails off in doubt and consternation. This voice flawlessly recites every state in these United States* as the class and teacher stare in awe, and at the very end the resounding voice makes mention of Puerto Rico and Guam as territories. The teacher wordlessly hands over two jolly ranchers.

A new day. List the presidents. Nobody knows beyond Washington, Lincoln, FDR, JFK, Clinton, George W. Bush–the incumbent finishing up his final term in a few months. Except. One voice–just as triumphant–recites every president, in order, even making mention of Grover Cleveland's non-consecutive second term. Everyone–teacher and student alike–stares again, this time almost in horror. The voice, embarrassed and blushing at the stares this time, finishes the forty-three chronologically, and this time as the teacher hands over another two jolly ranchers she overcomes her shock to ask "How did you know that??"

At which the body that contains the voice shrugs sheepishly, pops a blue raspberry in their mouth, and makes a vague "I 'unno" sound–unwilling to admit that the Fifty Nifty song they sang with their class in a third grade recital had permanently seared itself into their brain, as did the Nickelodeon presidents song that aired during the Oh Four election between Bush and Kerry

*I realized after while at dinner that evening when I told my parents about it that I had completely skipped Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, but the listing was so smooth and confident that no one noticed. I never made that mistake again regardless

#american history#jolly ranchers#at one point our teacher in her infinite wisdom decided to announce our grades without our names attached#and had us guess who got what score. why she thought this was a good idea i do not know#but everyone immediately singled me out as one of two completely one hundred percenters. they were wrong tho#i was too chronically exhausted after school to do any kind of homework so i was pulling solid Bs#this class was kinda worthless tho because my teacher–who in respect was really micro/agressive towards Black students–#taught us that 'we' had won the Battle Of Corydon in the civil war#naturally since Indiana was a Union state i took that to mean the Union won the battle and carried that knowledge for years#until one day looking it up on Wikipedia to prove a point to theta i found out the Union LOST the battle of Corydon#and either my American history teacher was an incompetent or she was a Confederate sympathizer with her 'we won' remark#which in retrospect she prolly was#anyway#tagging my hometown because i'm petty#Richmond Indiana

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

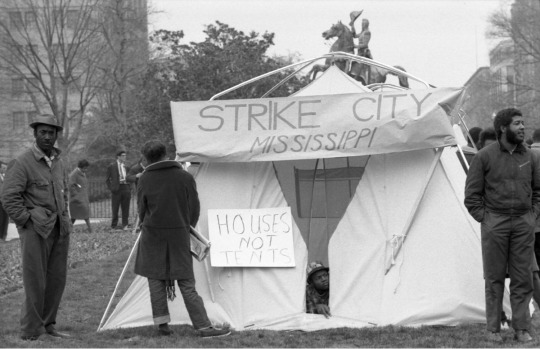

What Happened When a Fearless Group of Mississippi Sharecroppers Founded Their Own City

Strike City was born after one small community left the plantation to live on their own terms

— September 11, 2023 | NOVA—BPS

A tin sign demarcated the boundary of Strike City just outside Leland, Mississippi. Photo by Charlie Steiner

In 1965 in the Mississippi Delta, things were not all that different than they had been 100 years earlier. Cotton was still King—and somebody needed to pick it. After the abolition of slavery, much of the labor for the region’s cotton economy was provided by Black sharecroppers, who were not technically enslaved, but operated in much the same way: working the fields of white plantation owners for essentially no profit. To make matters worse, by 1965, mechanized agriculture began to push sharecroppers out of what little employment they had. Many in the Delta had reached their breaking point.

In April of that year, following months of organizing, 45 local farm workers founded the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. The MFLU’s platform included demands for a minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, medical coverage and an end to plantation work for children under the age of 16, whose educations were severely compromised by the sharecropping system. Within weeks of its founding, strikes under the MFLU banner began to spread across the Delta.

Five miles outside the small town of Leland, Mississippi, a group of Black Tenant Farmers led by John Henry Sylvester voted to go on strike. Sylvester, a tractor driver and mechanic at the A.L. Andrews Plantation, wanted fair treatment and prospects for a better future for his family. “I don’t want my children to grow up dumb like I did,” he told a reporter, with characteristic humility. In fact it was Sylvester’s organizational prowess and vision that gave the strikers direction and resolve. They would need both. The Andrews workers were immediately evicted from their homes. Undeterred, they moved their families to a local building owned by a Baptist Educational Association, but were eventually evicted there as well.

After two months of striking, and now facing homelessness for a second time, the strikers made a bold move. With just 13 donated tents, the strikers bought five acres of land from a local Black Farmer and decided that they would remain there, on strike, for as long as it took. Strike City was born. Frank Smith was a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worker when he went to live with the strikers just outside Leland. “They wanted to stay within eyesight of the plantation,” said Smith, now Executive Director of the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C. “They were not scared.”

Life in Strike City was difficult. Not only did the strikers have to deal with one of Missississippi’s coldest winters in history, they also had to endure the periodic gunshots fired by white agitators over their tents at night. Yet the strikers were determined. “We ain’t going out of the state of Mississippi. We gonna stay right here, fighting for what is ours,” one of them told a documentary film team, who captured the strikers’ daily experience in a short film called “Strike City.” “We decided we wouldn’t run,” another assented. “If we run now, we always will be running.”

But the strikers knew that if their city was going to survive, they would need more resources. In an effort to secure federal grants from the federal government’s Office of Economic Opportunity, the strikers, led by Sylvester and Smith, journeyed all the way to Washington D.C. “We’re here because Washington seems to run on a different schedule,” Smith told congressmen, stressing the urgency of the situation and the group’s needs for funds. “We have to get started right away. When you live in a tent and people shoot at you at night and your kids can’t take a bath and your wife has no privacy, a month can be a long time, even a day…Kids can’t grow up in Strike City and have any kind of a chance.” In a symbolic demonstration of their plight, the strikers set up a row of tents across the street from the White House.

John Henry Sylvester, left, stands outside one of the tents strikers erected in Washington, D.C. in April 1966. Photo by Rowland Sherman

“It was a good, dramatic, in-your-face presentation,” Smith told American Experience, nearly 60 years after the strikers camped out. “It didn’t do much to shake anything out of the Congress of the United States or the President and his Cabinet. But it gave us a feeling that we’d done something to help ourselves.” The protestors returned home empty-handed. Nevertheless, the residents of Strike City had secured enough funds from a Chicago-based organization to begin the construction of permanent brick homes; and to provide local Black children with a literacy program, which was held in a wood-and-cinder-block community center they erected.

The long-term sustainability of Strike City, however, depended on the creation of a self-sufficient economy. Early on, Strike City residents had earned money by handcrafting nativity scenes, but this proved inadequate. Soon, Strike City residents were planning on constructing a brick factory that would provide employment and building material for the settlement’s expansion. But the $25,000 price tag of the project proved to be too much, and with no employment, many strikers began to drift away. Strike City never recovered.

Still, its direct impact was apparent when, in 1965, Mississippi schools reluctantly complied with the 1964 Civil Rights Act by offering a freedom-of-choice period in which children were purportedly allowed to register at any school of their choice. In reality, however, most Black parents were too afraid to send their children to all-white schools—except for the parents living at Strike City who had already radically declared their independence . Once Leland’s public schools were legally open to them, Strike City kids were the first ones to register. Their parents’ determination to give them a better life had already begun to pay dividends.

Smith recalled driving Strike City’s children to their first day of school in the fall of 1970. “I remember when I dropped them off, they jumped out and ran in, and I said, ‘They don't have a clue what they were getting themselves into.’ But you know kids are innocent and they’re always braver than we think they are. And they went in there like it was their schoolhouse. Like they belonged there like everybody else.”

#The Harvest | Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article#NOVA | PBS#American 🇺🇸 Experience#Mississippi Delta#Cotton | King#Abolition | Slavery#Black Sharecroppers#Mechanized Agriculture#Mississippi Freedom Labor Union (MFLU)#Leland | Mississippi#Black Tenant Farmers#John Henry Sylvester | Truck Driver | Mechanic#A.L. Andrews Plantation#Fair Treatment | Prospects#Baptist Educational Association#Frank Smith | Student | Nonviolent Coordinating Committee#Strike City#Executive Director | African American | Civil War Memorial & Museum | Washington D.C.#Federal Government | Office of Economic Opportunity#Congress of the United States | The President | Cabinet#Brick Homes | Black Children | Literacy Program#Wood-and-Cinder-Block | Community Center

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have to serve cunt too many times in one weekend

#my god#there’s so much shit happening#a gala for the the black student Union on campus#obvi gonna eat for that#then my poetry showcase that#hold on#they are announcing me as next years president 🫡🫣#it would be a crime if I didn’t show tf out duh#current concerns

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

nah instagram keeps recommending an acct to me whose entire shtick is that our very catholic college is not catholic enough, with such delightful posts as "genuinely comparing being pro choice to racism" and "the secularists are trying to destroy religion on campus by cancelling a guest speaker"

#aka that time abby fucking johnson was brought in to speak about abortion#and like half the student body including basically every minority and international student union#and lots and lots of self identified catholics#spoke out#and in turn hosted their own competing event about how the pro life movement is MORE than just being anti abortion#because abby johnson is a straight up racist like....i don't even care if you believe her stupid planned parenthood rhetoric#(even though it's largely bullshit)#she's a straight up racist and it should not exactly be shocking why. for example.#the latino student union. the filipino student union. and the black student union. all protested and held a counter event.#people didn't even make this big of a stink about matt walsh speaking here last year either#i mean some people did but nowhere near the volume of outrage. sigh#girl catholic is in the name of the fucking university. the fuck are you complaining about.#i wanna talk about me#also if you read this far and want to try and extrapolate where i go to school do me a favor and Don't#i want to complain i don't want to be doxxed thanks.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

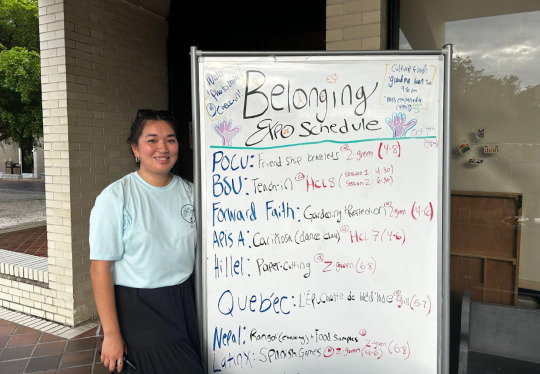

First Belonging Expo promotes Inclusion on Campus

Oct. 7 marked the day of the Student Activities & Campus Engagement (SAUCE) office’s first Belonging Expo, opening doors for students to engage with various affinity clubs and one another. Thesis student and Student Event Team (SET) Belonging Coordinator Celeste Kadzis has spent the past three years organizing similar, individual events encouraging campus-wide involvement and togetherness.

“This…

View On WordPress

#belonging expo#Black Student Union#bsu#counseling and wellness center#CWC#forward faith#hillel#people of color union#pocu#sauce#student activities#student event team

0 notes

Text

mmmm I love my university having classes cancelled tomorrow after a tirade of hate crimes and gun threats against black students!!! God I fucking hate it here!!!

#tw racism#fucking god damn#students on this campus really thought “ah yes let’s carve the n word into black girls dorm doors”#“ah yes when people get rightfully upset about this and host a protest on campus we’re going to threaten to shoot it up”#“and skin the members of the black student Union”#I FUCKING HATE IT HERE

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

If they HAD to be, what high school clubs would Ryan and Sophie be part of?

Sophie Ryan

Send me an ask about a character or ship or one of my fics and I can only respond with something on my Pinterest board for said character/ship/fic? Or a song from my playlists for them?

Wildmoore Cadina Academy Bros etc

#ask game#i know its cadet kelly ghkslg Sophie would be in rotc is what i'm saying#also probably student council#big brothers big sisters isn't a school thing but i wanted to give something different because#Ryan would also obviously be in some martial arts thing or a black student union#maybe not in hs but if she went to college she definitely would've been part of the bsu

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Although the war was an increasingly salient issue for the [Union Theological Seminary] Eight, everything in their backgrounds made them conscious of race as a source of egregious injustice in American life. Now Meredith Dallas was doing fieldwork in East Harlem. David Dellinger, in addition to his work at Dwight Hall, had witnessed Jim Crow firsthand during visits to his father’s family in the South. His fieldwork now was in a poor black area of Newark, New Jersey. The Eight were frustrated by the turn away from pacifism at Union, where many students and faculty, like most Americans, shifted to more of a traditional peace-through-strength stance as a result of developments in Europe. And they were all too conscious of the poverty and injustice practically right outside the door of their own institution [in New York].

It was probably Dellinger, with his confidence, seniority, and more radical instincts, who led some of the students out of the classroom and into the community. Despite his antipathy toward status and hierarchy, he was elected president of his class. He was older than most of the first-year students, was a graduate of Yale rather than a religious college in the hinterlands, had seen the Spanish Civil War up close, and had even visited Nazi Germany. He also had a year at Oxford under his belt, and a couple more working at Yale’s Christian center. [He had also ridden the rails in the 1930s and had experienced poverty and working class misery first hand...] In his first year at Union he quickly formed a close bond with Don Benedict and Dallas, with whom he had classes, took meals, and lamented the turn of their most famous professor, Reinhold Niebuhr, away from pacifism. Don and Dal, as they were known, had been undergraduates at Albion College together and were both bound for the ministry. Dellinger, alienated from his parents, seemed to treat them as family, and late in 1939 they decided to move together to an impoverished section of nearby Harlem, a black neighborhood where they imagined their ramshackle apartment would function as a Gandhian ashram.

They were not alone in pursuing Protestant pacifism as a “way of life,” far beyond merely eschewing violence. In Aurora, Ohio, a handful of Antioch College students gained attention for a cooperative farm called Ahimsa, named for the Indian religious doctrine of nonviolence, where they grew food and studied key pacifist texts including Gregg’s The Power of Non-Violence. Emulating Gandhi, they also launched a small march to the sea, in this case to focus attention on European hunger. Ahimsa didn’t last beyond 1942, but supporters included A. J. Muste and the British pacifist Muriel Lester. Ahimsa’s founders, through a connection with a black church in Cleveland, would become involved in a small nonviolent protest that was to have large ramifications.

Closer to Union, Jay Holmes Smith and Ralph Templin, Methodist missionaries essentially expelled from India for siding with Gandhi, launched their Harlem Ashram on Fifth Avenue near 125th Street in the winter of 1940–41 (situated, incongruously, opposite a tavern called the Bucket of Blood). It soon became a center for pacifist absolutists, including those who refused to register. From the discussions in its dingy rooms arose the Non-Violent Direct Action Committee, whose commitment to direct action was evident in its name, and the Free India Committee, a group that included many prominent activists (such as A. Phillip Randolph), and which in 1943 frequently demonstrated at the British consulate in New York and embassy in Washington. The protesters were usually arrested. Ashram residents at various times included future civil rights luminaries James Farmer and Pauli Murray as well as Krishnalal Shridharani, whose War Without Violence, published in 1939, quickly became a Gandhian handbook for American pacifists. “Shridharani’s book became our gospel, our bible,” said Bayard Rustin, who lived nearby for a while and was a frequent visitor. The ashram only lasted until 1944, when it succumbed to financial and other issues, including perhaps an excess of piety. Farmer called the furniture “old, cheap and tasteless,” and the meals “an inducement to fasting.” He recalls Smith once violating the usual dinner etiquette by serving the soup to himself first, thereby giving him a chance to discreetly ladle a cockroach out of it before it became visible to the other diners.

While it lasted, the Harlem Ashram was an important test bed for the Fellowship and its members to break out in new directions. Shridharani, three blacks, and seven whites lived there at the outset, around January of 1941, and a Fellowship of Reconciliation nonviolent direct action group began meeting there. Smith and John Swomley, Jr., soon launched a summer training school in “total pacifism,” which they portrayed in familiar Christian terms, including as “a way of life, in which we seek to live out the implications of truth and non-violence in all our relationships,” and “a goal for social reconstruction, a co-operative socio-economic order, approximating to the realization of the Kingdom of God on earth.” But they added something of more recent vintage: “Non-violent action.” They surveyed black Harlem residents about discrimination, and launched a campaign to desegregate New York’s YMCAs. In a pamphlet about the ashram, they wrote: “We Live in Harlem because we regard the problem of racial justice as America’s No. 1 problem in reconciliation.”

Accordingly, in the fall of 1942 Smith led fourteen marchers on an “Interracial Pilgrimage” to dramatize the anti-lynching and anti–poll tax bills then before Congress. The group walked from New York to Washington, D.C., carrying signs condemning discrimination, and also met with townspeople en route. It was an idealistic bunch. For symbolic reasons they trod the Lincoln Highway, and they debated whether they could allow the police to protect them from the hostility they encountered along the way. The activist Ruth Reynolds marched until her feet bled, and still refused to stop. Finally, trailing blood on the sidewalks of Philadelphia, she was arrested just to get her into an ambulance. After emergency care, she rejoined the group and finished the march. Father Divine’s followers fed them all in Wilmington. When they wearily trudged into Washington, their journey ended anticlimactically when a minor White House functionary accepted their petitions. The black civil rights lawyer Conrad Lynn reflected on his participation uneasily. Like most black Americans, he was no pacifist. Later he wrote that “the elevation of nonviolence and orderliness as means, often vitiated the desired end,” making the march mostly a “catharsis for the white people who participated” while blacks got only “suppression of indignation and a lesson in humility.”

As is evident from outposts like the Harlem Ashram and Ahimsa, the boys from Union were part of a rich vein of radicals launching intentional communities in the forties, many of them interracial ashrams, utopian farming ventures, and Fellowship Houses founded to promulgate nonviolent change. The years ahead would produce many more. After the war, Dellinger and his family would live on a cooperative farm in New Jersey with a few likeminded families, eventually naming the place Saint Francis Acres and “changing the deed to declare that the land belonged to God.”

Meanwhile he was looking for something more than a mere academic experience from his time at Union—and besides, “I didn’t believe in a community that had no meaningful associations with its poor, radically oppressed neighbors.” Benedict was under no illusions that by living among the poor the fellows could do them much good, but he could at least show whose side he was on and learn from dwelling among the dispossessed. “My quarrel was not with the school,” he writes, “but with its tacit elitism. In the gospel there was no place for elitism.”

...

When they “finally found a place wretched enough to please us,” as Benedict wryly recalled, they learned firsthand what it was like to live in bedbug-infested quarters with virtually no heat and run a gauntlet of derelicts and prostitutes to get home at night. Residents of the neighborhood were understandably wary of these young white guys. But Dellinger got to know people through sports, “playing stickball, shooting pool, having beer, and listening to the ball game at the corner bar, hanging out on the stoop on a hot night,” and doing other things that neighbors might naturally do together. As Spragg put it, “We wanted to go down there to find out what the real world was like.”

One or another of the seminarians might bring home a lost soul, who usually left fed and cleaned up. Benedict recalls encountering, one freezing night, “a large, hulking fellow, revoltingly dirty and frowzy, altogether a disgusting sight, steeped in the sour smell of vomit and the stench of alcohol.” Benedict was ashamed that he at first recoiled from the man’s entreaties, and so, with Dallas, brought him home, where they treated a nasty abrasion and provided clean pajamas. Spragg, who was senior class president, was on hand and challenged them, arguing that they weren’t going to do much good one drunk at a time and needed to address much larger social issues to bring about any appreciable change. Spragg had played football at Tufts, yet he, too, was a pacifist, having read Niebuhr on this score, and a Norman Thomas socialist as well. He was another of those shaped by the Christian student activism of the day. For five straight summers he had accepted difficult assignments for the Congregational Church home mission, including two organizing stints in Harlan County, Kentucky, for the United Mine Workers.

Another time Dallas brought home a couple of guys he’d met in a bar. They were supposedly trying to get together a tap-dancing act and had no place to stay. After a few days the dancers vanished with their hosts’ typewriters and clothes. Dellinger’s flute was stolen at one point. Later he said of the thief, “Painful as the loss was, I knew that I had been less wronged by him than he by the society that provided me with a silver flute and him with a drug habit.” At Union there was a certain amount of ridicule for what the fellows were doing. But there was admiration as well, and when they held an open house, many students and faculty members showed up. Some fellow students started volunteering in their spare time. And Dallas got the chance to preach out in the community, including at Fosdick’s Riverside Church. Adam Clayton Powell’s Abyssinian Baptist Church left a particular impression. “I was up there in the pulpit,” he recalled years later, “and I could get that wave of energy from the congregation that happens in a black church. My God! That was powerful.”

- Daniel Akst, War By Other Means: How the Pacifists of World War 2 Changed American for Good. New York: Melville House, 2022. p. 110-114.

#conscientious objectors#pacifism#world war ii#united states history#anti-war#gandhian nonviolence#war resisters#indian freedom struggle#nonviolence#research quote#reading 2024#american prison system#black freedom struggle#seminary students#new york#harlem#ashram#union theological seminary

0 notes

Text

got triggered by violent misogynoir the first day of school

17 notes

·

View notes