#Essays Moral Political and Literary

Quote

Weakness, fear, melancholy, together with ignorance, are the true sources of superstition.

David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary

#philosophy#quotes#David Hume#Essays Moral Political and Literary#fear#ignorance#superstitions#beliefs

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I Deliberately Avoided the "Colonizer" Argument in my Zutara Thesis - and Why I'll Continue to Avoid it Forever

This is a question that occasionally comes up under my Zutara video essay, because somehow in 2 hours worth of content I still didn't manage to address everything (lol.) But this argument specifically is one I made a point of avoiding entirely, and there are some slightly complicated reasons behind that. I figure I'll write them all out here.

From a surface-level perspective, Zuko's whole arc, his raison d'etre, is to be a de-colonizer. Zuko's redemption arc is kinda all about being a de-colonizer, and his redemption arc is probably like the most talked about plot point of ATLA, so from a basic media literacy standpoint, the whole argument is unsound in the first place, and on that basis alone I find it childish to even entertain as an argument worth engaging with, to be honest.

(At least one person in my comments pointed out that if any ship's "political implications" are problematic in some way, it really ought to be Maiko, as Mai herself is never shown or suggested to be a strong candidate for being a de-colonizing co-ruler alongside Zuko. If anything her attitudes towards lording over servants/underlings would make her… a less than suitable choice for this role, but I digress.)

But the reason I avoided rebutting this particular argument in my video goes deeper than that. From what I've observed of fandom discourse, I find that the colonizer argument is usually an attempt to smear the ship as "problematic" - i.e., this ship is an immoral dynamic, which would make it problematic to depict as canon (and by extension, if you ship it regardless, you're probably problematic yourself.)

And here is where I end up taking a stand that differentiates me from the more authoritarian sectors of fandom.

I'm not here to be the fandom morality police. When it comes to lit crit, I'm really just here to talk about good vs. bad writing. (And when I say "good", I mean structurally sound, thematically cohesive, etc; works that are well-written - I don't mean works that are morally virtuous. More on this in a minute.) So the whole colonizer angle isn't something I'm interested in discussing, for the same reason that I actually avoided discussing Katara "mothering" Aang or the "problematic" aspects of the Kataang ship (such as how he kissed her twice without her consent). My whole entire sections on "Kataang bad" or "Maiko bad" in my 2 hour video was specifically, "how are they written in a way that did a disservice to the story", and "how making them false leads would have created valuable meaning". I deliberately avoided making an argument that consisted purely of, "here's how Kataang/Maiko toxic and Zutara wholesome, hence Zutara superiority, the end".

Why am I not willing to be the fandom morality police? Two reasons:

I don't really have a refined take on these subjects anyway.

Unless a piece of literature or art happens to touch on a particular issue that resonates with me personally, the moral value of art is something that doesn't usually spark my interest, so I rarely have much to say on it to begin with. On the whole "colonizer ship" subject specifically, other people who have more passion and knowledge than me on the topic can (and have) put their arguments into words far better than I ever could. I'm more than happy to defer to their take(s), because honestly, they can do these subjects justice in a way I can't. Passing the mic over to someone else is the most responsible thing I can do here, lol.

But more importantly:

I reject the conflation of literary merit with moral virtue.

It is my opinion that a good story well-told is not always, and does not have to be, a story free from moral vices/questionable themes. In my opinion, there are good problematic stories and bad "pure" stories and literally everything in between. To go one step further, I believe that there are ways that a romance can come off "icky", and then there are ways that it might actually be bad for the story, and meming/shitposting aside, the fact that these two things don't always neatly align is not only a truth I recognise about art but also one of those truths that makes art incredibly interesting to me! So on the one hand, I don't think it is either fair or accurate to conflate literary "goodness" with moral "goodness".

On a more serious note, I not only find this type of conflation unfair/inaccurate, I also find it potentially dangerous - and this is why I am really critical of this mindset beyond just disagreeing with it factually. What I see is that people who espouse this rhetoric tend to encourage (or even personally engage in) wilful blindness one way or the other, because ultimately, viewing art through these lens ends up boxing all art into either "morally permissible" or "morally impermissible" categories, and shames anyone enjoying art in the "morally impermissible" box. Unfortunately, I see a lot of people responding to this by A) making excuses for art that they guiltily love despite its problematic elements and/or B) denying the value of any art that they are unable to defend as free from moral wickedness.

Now, I'm not saying that media shouldn't be critiqued on its moral virtue. I actually think morally critiquing art has its place, and assuming it's being done in good faith, it absolutely should be done, and probably even more often than it is now.

Because here's the truth: Sometimes, a story can be really good. Sometimes, you can have a genuinely amazing story with well developed characters and powerful themes that resonate deeply with anyone who reads it. Sometimes, a story can be all of these things - and still be problematic.*

(Or, sometimes a story can be all of those things, and still be written by a problematic author.)

That's why I say, when people conflate moral art with good art, they become blind to the possibility that the art they like being potentially immoral (or vice versa). If only "bad art" is immoral, how can the art that tells the story hitting all the right beats and with perfect rhythm and emotional depth, be ever problematic?

(And how can the art I love, be ever problematic?)

This is why I reject the idea that literary merit = moral virtue (or vice versa) - because I do care about holding art accountable. Even the art that is "good art". Actually, especially the art that is "good art". Especially the art that is well loved and respected and appreciated. The failure to distinguish literary critique from moral critique bothers me on a personal level because I think that conflating the two results in the detriment of both - the latter being the most concerning to me, actually.

So while I respect the inherent value of moral criticism, I'm really not a fan of any argument that presents moral criticism as equivalent to literary criticism, and I will call that out when I see it. And from what I've observed, a lot of the "but Zutara is a colonizer ship" tries to do exactly that, which is why I find it a dishonest and frankly harmful media analysis framework to begin with.

But even when it is done in good faith, moral criticism of art is also just something I personally am neither interested nor good at talking about, and I prefer to talk about the things that I am interested and good at talking about.

(And some people are genuinely good at tackling the moral side of things! I mean, I for one really enjoyed Lindsay Ellis's take on Rent contextualising it within the broader political landscape at the time to show how it's not the progressive queer story it might otherwise appear to be. Moral critique has value, and has its place, and there are definitely circumstances where it can lead to societal progress. Just because I'm not personally interested in addressing it doesn't mean nobody else can do it let alone that nobody else should do it, but also, just because it can and should be done, doesn't mean that it's the only "one true way" to approach lit crit by anyone ever. You know, sometimes... two things… can be true… at once?)

Anyway, if anyone reading this far has recognised that this is basically a variant of the proship vs. antiship debate, you're right, it is. And on that note, I'm just going to leave some links here. I've said about as much as I'm willing/able to say on this subject, but in case anyone is interested in delving deeper into the philosophy behind my convictions, including why I believe leftist authoritarian rhetoric is harmful, and why the whole "but it would be problematic in real life" is an anti-ship argument that doesn't always hold up to scrutiny, I highly recommend these posts/threads:

In general this blog is pretty solid; I agree with almost all of their takes - though they focus more specifically on fanfic/fanart than mainstream media, and I think quite a lot of their arguments are at least somewhat appropriate to extrapolate to mainstream media as well.

I also strongly recommend Bob Altemeyer's book "The Authoritarians" which the author, a verified giga chad, actually made free to download as a pdf, here. His work focuses primarily on right-wing authoritarians, but a lot of his research and conclusions are, you guessed it, applicable to left-wing authoritarians also.

And if you're an anti yourself, welp, you won't find support from me here. This is not an anti-ship safe space, sorrynotsorry 👆

In conclusion, honestly any "but Zutara is problematic" argument is one I'm likely to consider unsound to begin with, let alone the "Zutara is a colonizer ship" argument - but even if it wasn't, it's not something I'm interested in discussing, even if I recognise there are contexts where these discussions have value. I resent the idea that just because I have refined opinions on one aspect of a discussion means I must have (and be willing to preach) refined opinions on all aspects of said discussion. (I don't mean to sound reproachful here - actually the vast majority of the comments I get on my video/tumblr are really sweet and respectful, but I do get a handful of silly comments here and there and I'm at the point where I do feel like this is something worth saying.) Anyway, I'm quite happy to defer to other analysts who have the passion and knowledge to give complicated topics the justice they deserve. All I request is that care is taken not to conflate literary criticism with moral criticism to the detriment of both - and I think it's important to acknowledge when that is indeed happening. And respectfully, don't expect me to give my own take on the matter when other people are already willing and able to put their thoughts into words so much better than me. Peace ✌

*P.S. This works for real life too, by the way. There are people out there who are genuinely not only charming and likeable, but also generous, charitable and warm to the vast majority of the people they know. They may also be amazing at their work, and if they have a job that involves saving lives like firefighting or surgery or w.e, they may even be the reason dozens of people are still alive today. They may honestly do a lot of things you'd have to concede are "good" deeds.

They may be all of these things, and still be someone's abuser. 🙃

Two things can be true at once. It's important never to forget that.

#zutara discourse#the colonizer argument#anti anti zutara#text post#long post#anti maiko#anti mai#tagging just in case#anti purity culture#this is not an anti-ship safe space

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading on reading

a literary syllabus [x]

how to read now by elaine castillo

a collection of essays by novelist and essayist elaine castillo about the politics and ethics of reading. castillo exposes the inherently colonial premises behind not only the works of many individual writers; but the way reading cultures analyze and canonize works, the tokenizing nature of the publishing industry that fails writers and readers of color, and the unfulfilled promises by bibliophiles and literary institutions to "build empathy" through reading diverse books.

"time in the codex" and "lastingness" by lisa robertson

two essays by poet lisa robertson from her prose collection nilling, both meditations on reading. “time in the codex” is an ode to the sensory and cognitive processes that reading evokes. “lastingness” explores the relationship between passivity and will when it comes to receiving the stories and ideas we read, using the work of hannah arendt to analyze texts by lucretius and pauline réage.

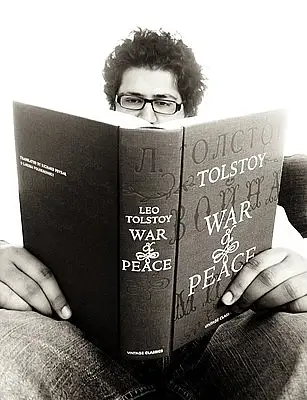

a history of reading by alberto manguel

alberto manguel (former director of argentina's national library) compiles a history of reading that encompasses the prehistory of books in ancient mesopotamia, the story of the library of alexandria and its influence in libraries that followed, literary societies such as the heian court, book thieves throughout time, book banning in multiple cultures, and the progression of text formats around the world from clay tablets to modern bookbinding.

selections from not to read by alejandro zambra (trans. megan mcdowell)

essays taken from the collection not to read by chilean writer alejandro zambra about the practice of reading, his own evolving reading life, and writing books; mixed with a variety of literary criticism. selections include "in praise of the photocopy," "against poets," "obligatory readings," "traveling with books," and "novels-- forget it."

"how do we read?", "the reading ape", and "inventing reading" by stanislas dahaene

three chapters from cognitive neuroscientist stainslas dahaene's book reading in the brain. "how do we read?" functionally breaks down how our brain understands written words. "the reading ape" imagines how our ability to read evolved by recycling preexisting neural circuits. "inventing reading" explores how languages themselves have formed over time to serve the way we think.

"when robots read books" by inderjeet mani

essay by computational linguist inderjeet mani on ways that artificial intelligence could enhance literary criticism by analyzing classic texts, particularly cumulative corpuses of works. examples of literary AI usage include finding similar character traits, archetypes, and tropes between different books and authors; quantitatively tracking literary trends; and generating timelines and maps of information pulled from narratives.

"uncritical reading" by michael warner

essay by english professor michael warner which attempts to define what "critical reading" actually is, the beginnings of a history of that practice, its alignment with agency and morality in academic culture, and what the qualities of "uncritical reading" (such as “identification, self-forgetfulness, reverie, sentimentality, enthusiasm, literalism, aversion, distraction") might offer us.

"someone reading a book is a sign of order in the world" by mary ruefle

essay adapted from a lecture in poet mary ruefle’s madness, rack, and honey that traces a reader's development through personal experiences in her own reading life. topics include rereading, what it means to read “the right book at the right time”, and the pleasure of finding imaginative connections between books.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

One day I'll probably do a 40-minute video essay on this topic, but the internet's misinterpretation of "Death of the Author" is just a real shame.

I frequently see the concept brought up in relation to a certain terf author. People attempt to 'separate the work and the author', but that is frankly not how it is intended to be used.

"Death of the Author" is supposed to be a tool for literary analysis. That's all it is. It is not a theory by itself, nor a political stance or a way to judge morality.

It is a tool to encourage readers to interpret the content of a text authentically, but you should use it critically, and be aware of why, how and when it is relevant. It is not an excuse to ignore context or paratext, as both of those should also be considered in a proper analysis.

The tool was developed during a time when the discourse was more favourable towards an author's intention rather than a reader's interpretation. People used intention to dismiss other readers' analysis of texts, using diary entries or letters by dead authors to counter less mainstream takes of canon texts. It was a period where the 'goal' of literary analysis was to uncover a text's true meaning. The original essay was a short controversial counterargument but the conversations it sparked over the following decades have led to the scale tipping more in favour of interpretation. It has also led to a 180 of the original problem.

Killing the author has the potential of empowering readers and encouraging deeper. Maybe even uncovering biases the author wasn't even aware of! However, (mostly outside of academic circles but not always) people are misusing the concept and use it to dismiss context and racist dog-whistles as well as discourage readings that rely more on subtext.

In simple terms we have gone from a mentality saying "AHA, I have evidence and it said you are wrong" to "AHA, it doesn't matter and therefore you are wrong". Neither is constructive in a conversation about art.

If you use the death of the author effectively while acknowledging intention and context you actually add a lot of nuance to your analysis, and doing so can demonstrate your analytical abilities. You will be able to distinguish what the text is saying plainly, what is said between the lines, and if the narrative effectively handles what it originally claimed. It is an effective 1-2 punch. Let me give you an ultra-short example:

On the surface level, '50 Shades of Grey' tells you that it is a sexy BDSM story. Throughout interviews and promotional material, E. L. James frames her story as a female-empowering book. But by critically examining how the books handle themes of consent, privacy, agency etc. we can argue that the narrative doesn't live up to proper BDSM conduct and that the protagonist is not empowered, and is instead displaying an unhealthy relationship. If we take the analysis further we could make an argument about what this says about society at large. Does it normalise boundary-breaking behaviour? Could it make someone romanticise stalking? The thesis statement is all up to you. (disclaimer I have not actually read these books, don't come for me, this is an example)

Here is what we just did: I presented a surface reading of a text. I presented the most likely intention of the author. I then argued for my interpretation by looking at literary themes and context. I used the conflict between Jame's intention, and my interpretation to illustrate a conflict. 1-2 punch. I am not killing James, I consider her opinion and intention to strengthen my argument, but I don't let her word of god determine or dismiss my reading. In just 3 simple sentences I use a variety of resources from my toolbox.

When people weaponise the author's intention it can look like this:

"Well, E. L. James said it is a female power fantasy, you're just reading too much into it" <- dismissing context and subtext by using 'word of god'. Weighing intention above interpretation.

"Does it really matter that E. L. James didn't research BDSM before publishing, can't it just be a sexy book?" <- dismissing context, subtext as well as author intention and accountability. Weighing their own interpretation and subtly killing the author

Simply exclaiming "I believe in death of the author" (which I have heard in Lit classes) means nothing. It's nothing. Except that you want to ignore context and only indulge in the parts of the text that you find enjoyable.

In the plainest way I can put it, the death of the author is supposed to make you say: "the author probably meant A, but the text and the context is saying B, therefore I conclude C". Don't just repeat what the author says. Don't just ignore context. And allow the feelings the text invokes in you to be there and let them be something you reflect on. The details you pick up on will be completely unique to you, the meaning you get will be just your own. You can do all of these things at once, I promise it doesn't have to be one or the other.

There has to be a balance. Intention matters. Interpretation matter. Watch out and pay attention. Are you only claiming the author is dead or alive when it serves your own narrative?

When you want to ignore an author ask why

When you don't want to read a book because you don't condone the actions of the author ask why

Examine how you dismiss arguments and how you further conversations.

#literature#lit#uni#death of the author#i don't write long tumblr posts what the fuck is this#i take constructive criticism but be nice about it#English is not my first language there are probably a ton of mistakes and weird things in this#analysis#i'll probably delete this thing#but i'll post it for now i guess because I have been writing on it for too long

644 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trope chats: Dark academia

Dark Academia, a cultural aesthetic and literary genre, has surged in popularity in recent years, captivating audiences with its blend of intellectualism, mystery, and darkness. This essay delves into the evolution, appeal, defining features, and potential pitfalls of Dark Academia in literature and media, exploring its cultural significance and enduring allure.

Dark Academia finds its roots in gothic literature and classical themes, drawing inspiration from works such as Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" and Edgar Allan Poe's macabre tales. However, its modern incarnation began to take shape in the early 20th century with novels like "The Secret History" by Donna Tartt and "Brideshead Revisited" by Evelyn Waugh. These works introduced themes of intellectualism, elitism, and moral ambiguity set within academic institutions.

Dark Academia's appeal lies in its romanticization of academia, coupled with elements of mystery, rebellion, and existential angst. Its depiction of ivy-covered campuses, candlelit libraries, and passionate debates evokes a sense of nostalgia and longing for a bygone era. Moreover, its exploration of complex characters grappling with ethical dilemmas and existential questions resonates with audiences seeking depth and introspection in their media consumption.

Defining Features of Dark Academia:

Academic Setting: Dark Academia often unfolds within prestigious educational institutions such as universities, boarding schools, or libraries, emphasizing the pursuit of knowledge and intellectual discovery.

Aesthetic Sensibility: Characterized by vintage fashion, classical architecture, and atmospheric landscapes, Dark Academia embraces a nostalgic and timeless aesthetic that harkens back to eras past.

Themes of Morality and Mortality: Dark Academia delves into moral ambiguity, existential angst, and the inevitability of death, exploring the darker aspects of human nature and the human condition.

Intellectualism and Obsession: Protagonists in Dark Academia are often portrayed as intellectuals or artists consumed by their pursuit of knowledge, creativity, or a particular obsession, leading to ethical dilemmas and personal crises.

Rituals and Traditions: The genre frequently incorporates rituals, traditions, and secret societies, adding an element of mystery and intrigue to the narrative.

While Dark Academia offers a compelling exploration of intellectualism and existential themes, it is not without its pitfalls. Critics argue that it romanticizes elitism, perpetuates harmful stereotypes, and glorifies toxic behavior such as substance abuse, self-destructive tendencies, and elitist attitudes. Moreover, its emphasis on aestheticism and nostalgia may overshadow deeper social and political issues, leading to a superficial engagement with complex themes.

In recent years, Dark Academia has experienced a resurgence in literature, film, television, and social media, fueled by platforms like Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok. Contemporary works such as "If We Were Villains" by M.L. Rio and "Ninth House" by Leigh Bardugo have brought the genre to new audiences, blending elements of mystery, fantasy, and psychological suspense. Additionally, films like "Dead Poets Society" and "The Magicians" series have further popularized Dark Academia's themes and aesthetic sensibility, cementing its status as a cultural phenomenon.

Dark Academia stands as a multifaceted genre that explores the intersection of intellect, morality, and mortality within academic settings. Its evolution from gothic literature to a modern cultural aesthetic reflects a timeless fascination with the pursuit of knowledge and the darker aspects of human nature. While its appeal lies in its romanticization of academia and exploration of existential themes, Dark Academia also faces criticism for its potential to glorify elitism and toxic behavior. Nevertheless, its enduring allure continues to captivate audiences, ensuring its place in the literary and cultural landscape for generations to come.

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing#bookish#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books#fiction writing#how to write#writers#am writing#fantasy writer#female writers#story writing#teen writer#tumblr writers#tumblr writing community#writblr#writer problems#writer stuff#writerblr#writers community#writers life#writers corner#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writerscorner

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag Game: 9 Favorite Characters

I was tagged by @anyboli, @asha-mage, and @spectrum-color (Stop! stop! I’m already tagged!)

Aladdin (Disney’s Aladdin)

This is definitely where my love of the rogue-with-a-heart-of-gold archetype started. Lay the blame squarely at his bare feet. I watched all the sequels including the direct-to-VHS Aladdin and the King of Thieves.

2. Mat Cauthon (the Wheel of Time series)

He’s 12 different literary/historical/mythological references slapped together, chained to a lovable rogue archetype, rolled in accessories, doused in foreshadowing, and given #vampireproblems. He probably has ADHD and dyslexia and definitely has anxiety. I’m obsessed with him and I have the essays to prove it.

3. Fortuona Athaem Devi Paendrag (the Wheel of Time series)

Liking Mat is the gateway drug to liking Tuon, at least in my case. She’s so fucking weird and mysterious and infuriating and I really wanted to understand her and her role in the story. Then I wanted to figure out how to fix her. Now I still want all that but also I want to make her worse, make her make other people worse, and just generally Put Her In Situations. She is endlessly fascinating to me and I want to chew on her until I rip out her squeaker. Then I will put in another squeaker and the process will begin again. My username, originally chosen because somebody else snagged matrimonycauthon, has very appropriately become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

4. Ael i'Mhessian t'Rllalielu (the Rihannsu series)

No one should be surprised that I love Diane Duane’s take on the Romulans, and Ael is the archetypal honorable Romulan type that Star Trek originally introduced. As the aunt of the Romulan Commander in the Enterprise Incident (the Federation steals technology from the Romulans) she has good reasons to hate Captain Kirk and the Federation personally- but as the tagline says, when there is no help from her friends, she turns to her enemies. She’s the star of the Rihannsu Star Trek novels: start with either My Enemy, My Ally for the first book or the omnibus Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages.

5. Tertius Lydgate (Middlemarch)

I was trying to sum up what I like about him and I think it’s something about the quiet tragedy of good intentions and ambition getting banally corrupted by unquestioned systems, practical considerations, and bad but personally inevitable choices. If you’ve ever worked in nonprofits or a b-corp, you may recognize yourself in Lydgate in a way that will make you uncomfortable. Or maybe it’s just me? Anyway, go read Middlemarch. It is always the right time in your life to read Middlemarch.

6. Tau-Indi Bosoka (The Masquerade series)

I’m love them! Tau-Indi is such a sweet person, and they follow a favorite character arc of mine: characters whose assigned or chosen role is to be the best representative & highest expression of their specific ethical and political milieu, and then they experience or learn something that forever disqualifies them from their former role, and then they have to keep on existing and build their sense of morality and place in the world from the ground up, on firmer foundations than the ones they started with. Also an excellent foil to Baru.

7. Miriam Beckstein (the Merchant Princes series)

Merchant Princes is basically an isekai story where a biotech journalist finds out she’s a long-lost heir to a group of alternate-universe-teleporting refugees. It’s not actually very fun for her at first, but she’s making it work. I love competence porn and she definitely delivers, and there’s also a very sweet slow-burn romance tied up with her funding and leading the socialist revolution of yet another alternate universe.

8. Glimmer (new She-Ra)

Glimmer? She’s just my bisexual teleporting deeply morally questionable power fantasy, it’s not that deep. Also she’s hot and I love her hair.

9. Mark Pierre Vorkosigan (Vorkosigan series)

What an incredible foil! Every time I read him I’m so impressed by how fucked up he is and how hard he’s working to figure out who he is and develop in a direction he chooses. Control issues, daddy issues, sexuality issues, identity issues… he’s an entire wall of magazines and I think he’s just great.

Tagging: @unmarkedcards @veliseraptor @ameliarating @gunkreads @liesmyth and anyone else who wants to do it

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Beattie’s essay “On Fable and Romance” in Dissertations Moral and Political (1783) is a strange hotchpotch of derivative ideas (mainly Hurd’s) but also shows the impact that the success of modern romance was having on the thinking of critics. He repeats the common view of Don Quixote as a romance-buster: “This work no sooner appeared, than chivalry vanished, as snow melts before the sun. Mankind awoke as from a dream” (Beattie in Clery and Miles, Gothic Documents, p. 92). But his account of chivalric romance sounds just like the “Gothic stories” of Walpole and Reeve, with castles in an eternal state of delapidation, complete with winding passages, secret haunted chambers, and creaking hinges, and narratives revolving around tyranny, rapine, and the ravishing of maidens. In other words, literary history had become infected with present-day fantasy. The revival of romance seems to have encouraged Beattie to apply the term freely, as Walpole did, to every kind of modern fiction including the works of Richardson and Fielding. This, however, does not save the genre from a final unexpected condemnation: “Let not the usefulness of Romance-writing be estimated by the length of my discourse upon it. Romances are a dangerous recreation . . . and tend to corrupt the heart, and stimulate the passions.”

E. J. Clery, The genesis of “Gothic” fiction

#currently reading#this rules. sorry. anyone in this thread doing a dangerous recreation that corrupts the heart and stimulates the passions

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

craft essay a day #7

i was just talking with @volturialice about comedy writing, so it's something that's been on my mind, and i've never really written about it. so consider this an early draft of a future essay that's far more coherent.

"Funny Is the New Deep: An Exploration of the Comic Impulse" by Steve Almond, The Writer's Notebook II: Craft Essays from Tin House

beginner | intermediate | advanced | masterclass

filed under: comedy, meaning making

key terms: comic impulse (his), comic intention (mine)

summary

i was hesitant to read this essay because comedy is very important to me. i can handle bad craft essays but i'm not sure i can handle bad craft essays on comedy. but, i thought, if you're writing a craft essay on comedy, you're probably pretty funny. that's the thing about comedy: it's not usually inspected by the unfunny.

Almond opens with Aristotle's four modes of literature: the tragic, the epic, the lyric, and the comic. he disagrees with the common belief that tragedy and comedy are working in opposition to one another.

"In fact, the comic impulse almost always arises directly from our efforts to contend with tragedy. It is the safest and most reliable way to acknowledge our circumstances without being crushed by them."

he talks about how Aristophanes is the father of comedy, and goes on to discuss the history of comedy in literature, focusing mainly on Vonnegut who tried to write about the bombing of Dresden seriously before eventually, twenty years later, succumbing to his comic instinct and writing the very darkly comedic Slaughterhouse Five.

"...comedy is produced by determined confrontation with a set of feeling states that are essentially tragic in nature: grief, shame, disappointment, physical discomfort, anxiety, moral outrage. It is not about pleasing the reader. It's about purging the writer...Another way of saying this would be that the best comedy is rooted in the capacity to face unbearable emotions and to offer, by means of laughter, a dividend of forgiveness."

Almond asserts that humor is the result of being able to look at understand the wider picture, and that's why comedy can be so rooted in politics and current events. he acknowledges that what's funny is not objective, and concludes by saying,

"The real question isn't whether you can or should try to be funny in your work, but whether you're going to get yourself and your characters into enough danger to invoke the comic impulse. Literary artists don't write funny to produce laughter...but to apprehend and endure the astonishing sorrow of the examined life."

my thoughts are centered around the practicality of comedy writing, by which i mean to answer the question, but how do you be funny? and talk about what i'm calling "comic intention." (note, i came up with it just now and so i'm still Thinking on it, and my thoughts may be half-baked.)

my thoughts

this essay put me through all five stages of grief. i feel very personally called out in a paragraph about how, in a story when the stakes get too high, or as Almond says, "reaches a point of unbearable heaviness" the comic impulse is to make it funny. and i do that. and i'm so delighted by how clever and hilarious i am (sarcasm. see? he's right), and i value comedy so highly, that i'm always hesitant (or i even straight-out refuse) to change it. and he's right also, ultimately, that the impulse comes from a place of trauma, of habitually defusing. once, i was dating a guy who pulled a knife on me, and i said, "if you get my blood everywhere you're not going to get our security deposit back."

i read a certain sentiment by comedic literary authors over and over again: early in their careers, they stifled their own comic impulse in an effort to be taken seriously. they were inspired by hemingway and wanted to write dry prose of the very sober, somber variety. Almond admits this in the essay, and says the same of Vonnegut, and once i went to a lecture by George Saunders who said literally the same thing. and i'm like, what is wrong with you people? why in god's name would you ever take yourselves seriously enough to want to be taken seriously?

for me it was the inverse. it took me years to even want to take my work seriously, to think of it as anything other than fucking around and finding out. and i also take umbrage a little at the idea that comedy writing is fundamentally unserious. but then again, i revere comedy. to me being funny is the highest ideal. i believe if you can do comedy and do it well, you can do anything. comedic actors can almost always do drama, but not all dramatic actors can do comedy. one of the reasons breaking bad and better call saul are so successful is that they play on the charisma, wit, and insanely funny talent of two comic actors (Cranston and Odenkirk). they're the most serious shows you could ever watch, but they're still funny.

there's a difference i think between being serious and taking yourself seriously. the gravest creative sin, to me, is taking a story too seriously. if it's apparent the writer can't see the inherent potential humor of all things, even if that humor isn't played upon, even if no one's laughing, i am immediately ejected from a story. comedy is a wider breadth of understanding than the material offers. Almond makes this point too, and uses conservatives as an example, saying that Republicans aren't funny and that's a sign that they don't understand jackshit about anything.

i don't believe everything should be funny. but everything should acknowledge its own potential for humor.

okay so here's my big thought:

my reaction to this essay is a huge "yes, but..." i agree with Almond on nearly everything he says, except there are the nuts and bolts of joke-making to consider. and that happens in only two possible places: on the line level, the setup and the punchline; or the situational level, the concept of a story. a sitcom is a situational comedy, which means that the premise of the story itself must in some way be comedic. when writing comedy, these are the only two tools you've got. sentence and concept. that's it.

the show Barry (HBO) is, to me, the greatest example of comedy writing i've ever seen. situationally, it's hilarious: a hitman wants to be a famous actor. and on a smaller level, what it does exceptionally well is acknowledge that every character no matter how frightening or serious or tragic can be the comedic relief. this blew my mind and changed my entire understanding of character. and with that understanding, my work has become a lot funnier. my characters (i like to think) are more interesting and complicated, because any of them at any point can do either the setup or the punchline. when you have serious characters and a comedic relief, the serious characters can only do the setup, and the comedic relief does the punchline. and i believed that for a long time. i would look at the cast of characters in a given story and think, who's the funny one? and now, they're all given the power of comedic relief.

i guess if i had to define my "yes, but" response to this essay, i would say that yes, there's comic instinct, but there's also comic intention. it's having the guts to be outside the joke looking in, to consciously and at the risk of ruining the joke for yourself, engineer the funny thing. i would say comic intention begins with instinct. you have to understand the rhythm and cadence of a setup, the right timing and pacing of the punchline. in your first draft you have to see where your setups have naturally been built and in your second draft you nail the punchline.

when i edit comedic stories, that's all i do. i pay attention to the rhythm of the piece and i find where the setups are or could be, and i make a little margin note that says "punchline here."

comedy writing, to me, is basically math. and that's the least funny thing there is. but if i don't acknowledge it, if i don't approach it with intention, i never get to the punchline. and intention itself is delicate--people expect comedy to seem effortless, so if you look like you're trying to be funny, you're not funny.

all comedy is about expectation. the basic setup of a joke is setting an expectation, and the punchline is doing something with that expectation. if you want to get funnier, start thinking about the unexpected. start thinking of details in pairs. your character is standing in an elderly woman's kitchen. situationally, this might be funny. maybe your character is a deadly assassin, and the elderly woman has invited him in for a coffee. or, at the line level, what's the most unexpected thing to be in that kitchen, based on the collective knowledge of what an elderly woman's kitchen looks like? your character opens the cutlery drawer and finds a glock. or a dildo. or a human molar. what's important is acknowledging that the elderly woman's kitchen is the setup of a potential punchline. the task is pivoting the punchline against the expectations of her kitchen.

even if you don't do this comedically, the practice of finding these pockets of potential will improve your writing, because what's in that woman's cutlery drawer can help us understand who she is as a character. what does it say about her if her junk drawer is a mess versus if it's meticulously organized? if she has thirteen owl-themed clocks? a wall of harley-davidson paraphernalia? what will your evil assassin character do if her dentures are in a cup and the cat is about to paw the cup off the table?

for those who also want to become better editors, one of the greatest skills you can learn is to read something and see what's not there, instead of just what is.

overall, i really admire Almond for writing earnestly on this topic, when sincerity can often threaten comedy. he acknowledges that insecurity is at the heart of every joke (the drive and the need to make someone laugh) and so the greatest fear of a funny person is to ruin the joke.

craft essay a day tag | cross-posted on AO3 | ask me something

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discussion Presentation: Race and Representation

"Can't Hold Us Down"

"Can't Hold Us Down" by Christina Aguilera featuring Lil' Kim is a significant track from Aguilera's 2002 album "Stripped." Released in 2003 by RCA Records, this R&B and hip-hop song, marked by a dancehall outro, delves into themes of gender double standards and feminism. The track was written and produced by Scott Storch, with Aguilera and Matt Morris contributing to the songwriting. The song was distributed as a CD single across various countries and also received a 12-inch edition release in the United States. Lyrically, "Can't Hold Us Down" is a forthright critique of societal double standards, where men are often celebrated for behaviors that lead to women being negatively judged. This feminist anthem encourages women to be assertive and challenges the notion that women should be passive. Notably, the lyrics suggest a rebuke directed at rapper Eminem, who had previously referenced Aguilera in his songs. The song's reception was mixed. While some critics found the lyrics confrontational and empowering, others critiqued it as lackluster or a waste of talent. It garnered a nomination for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals at the 2004 Grammy Awards but did not win. Despite these mixed reviews, "Can't Hold Us Down" has been recognized as a feminist anthem and a significant piece in Aguilera's discography, marking an important moment in feminist pop music. Commercially, the single achieved notable success. It reached number 12 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and charted within the top ten in many countries worldwide. The music video for "Can't Hold Us Down," directed by David LaChapelle, was inspired by New York City's Lower East Side of the 1980s. Set on a Los Angeles soundstage, the video features a confrontation between Aguilera and a man, culminating in a symbolic act of defiance. The video, however, garnered some criticism for potentially conflicting with the song's feminist message due to its provocative nature.

youtube

"The Blackness of Blackness: A Critique on the Sign and the Signifying Monkey"

Tales of the Signifying Monkey, a symbol deeply entrenched in African American folklore. In the Blackness of Blackness essay, Henry Louis Gates' central thesis revolves around "signifying", which he argues, transcends mere linguistic meaning and embodies a form of cultural and political resistance, a way for African American writers to navigate and challenge the complexities of their social and historical contexts. Just as African American literary tradition has used signifying to assert identity and resist marginalization, contemporary artists like Christina Aguilera use music to voice similar struggles against societal constraints and injustices. In "Can't Hold Us Down", her direct confrontation of gender stereotypes and double standards mirrors the subversive nature of signifying in African American literature. She asserted:

"If a guy have three girls then he's the man,

He can even give her some head and sex her raw,

If a girl do the same then she's a whore."

The first line, "If a guy have three girls then he's the man," points to the common societal trope where men are often praised or admired for having multiple sexual partners. This is a reflection of a deeply ingrained mindset that equates masculinity with sexual conquest. The male is depicted as a figure of admiration for his ability to attract and engage with multiple partners, reinforcing traditional notions of male dominance and virility.

The second line, "He can even give her some head and sex her raw," delves into more explicit sexual territory, highlighting the freedom and lack of judgment men often experience in their sexual exploits. This line underscores the perceived entitlement of men to engage in sexual acts without fear of societal retribution or moral judgment.

And lastly, "If a girl do the same then she's a whore" sharply contrasts the previous malely behaviors, exposing the starkly different societal attitudes towards women who exhibit similar sexual behaviors. When a woman engages in the same level of sexual activity as her male counterparts, she is often subject to harsh judgment and derogatory labeling.

Overall, these lines criticize a pervasive societal hypocrisy where men and women are judged and valued differently for the same actions. In Gates' framework, the these lyrics can be seen as an act of 'signifying' against patriarchal structures. They reveal and critique the hypocrisy in societal attitudes toward sexuality, paralleling how African American writers use signifying to address and resist racial stereotypes and injustices.

“STEREOTYPE, REALISM AND THE STRUGGLE OVER REPRESENTATION”

In "Stereotype, Realism", Ella Shohat and Robert Stam delve into the field of media representation, particularly in cinema, focusing on the portrayal of ethnic, racial, and colonial subjects. They critique the narrow focus on verisimilitude in media representations, which often perpetuates stereotypes rather than challenging them. They argue that representations in media are a "delegation of voice", influencing public perception and understanding of various communities. Just as the authors critique the media's role in perpetuating stereotypes and reinforcing societal norms, Aguilera's song challenges the stereotypical representation of women as passive or submissive. She asserted 2 consecutive questions at the very beginning of the song:

So, what, am I not supposed to have an opinion?

Should I keep quiet just because I'm a woman?

Firstly, the rhetorical question "So what am I not supposed to have an opinion?" challenges the often unspoken rule that women should be passive or less vocal about their views, especially in domains traditionally dominated by men. This line questions the legitimacy of societal norms that dictate women's behavior, suggesting a rebellion against the idea that women's opinions are less valuable or should be suppressed.

The follow-up question, "Should I keep quiet just because I'm a woman?" further underscores the gender bias inherent in expectations around speech and expression. This line directly confronts the sexist notion that a woman's primary role is to be seen and not heard, a concept that has long been used to marginalize and silence women. By posing this question, Aguilera not only rejects this outdated stereotype but also empowers her listeners, particularly women, to question and resist these societal norms.

These lines, act as a form of counter-narrative, pushing against the dominant media, portraying the often marginalized or silenced women's voices. They also embodies the concept of "progressive realism" that Shohat and Stam discuss, where marginalized groups use media to combat dominant, stereotypical narratives. The song's assertive tone and its message of female empowerment and resistance against gender stereotypes exemplify an alternative narrative, one that challenges the traditional representations and pushes for a more nuanced, respectful portrayal of women.

Discussion Questions!

How do societal expectations regarding gender roles and sexuality manifest in today's dating culture, and what steps can individuals and communities take to address and change these double standards?

In what ways do current popular music and other forms of media challenge or reinforce stereotypes about gender and sexuality? Discuss with examples from recent years.

Reflect on the concept of "signifying" as a form of resistance. How do marginalized groups today use social media and other digital platforms to signify their identities and resist stereotypes?

Consider the role of media representation in shaping societal views. How can media producers, consumers, and critics work together to ensure more diverse and realistic portrayals of all genders and ethnicities?

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are your honest thought about your muse’s canon? (Ja'far)

Munday asks / Accepting

HE DESERVED BETTER.

So I take a lot of issue with p much everything that happens after the Alma Toran arc. There were a lot of rumors going around at the time that Ohtaka was being rushed to close things out bc interest in the series was waning or she was gearing to switch projects to Orient or smth, don't know how true that was but from what came out I think it might be reasonable. To keep this short and less literary analysis, I'll stick to my issues with just Ja'far and Ja'far centric things. And imma put it under a read more bc it got way longer than expected lmao

So I loved Ja'far as a character early on, I thought he was super interesting with his dual nature of the brutal assassin & loyal government official and he serves as a great counterpart to one of the most interesting characters in the series, Sinbad. He's someone who is resolute in his loyalty but unafraid to course correct Sinbad. He's a reminder to Sinbad's dark past and the primary motivator of a brighter future. But a lot of that gets lost in the final arc.

I think part of it has to do with Sinbad's character change from morally gray and emotionally complicated leader (something we don't see a lot in anime) to self-serving, fully corrupted 'villain'. I could write a whole damn essay on Sinbad. But in this shift, Ja'far becomes rather weak and disappears into the background.

He's no longer guiding Sinbad or reprimanding him when he goes too far. Instead, he seems suddenly blind to Sinbad's true motives and depressingly lost in the final conflict. Like if they had revealed that Arba had brainwashed him to stand down, I would believe it. Even in his final plea for Sinbad to come down from his high horse, we get a wishy washy, emotional argument that Sinbad easily charms his way out of. When you compare this to the scene at the beginning of season two or even in SnB at the end of the slave arc, it's like a totally different characters. In those scenes, Ja'far was unapologetically brutal, even slapping Sinbad to wake him up and give him a fierce reality check. He doesn't take any of the dour, half-assed promises to do better. He's mean and in SnB he reminds Sinbad that he promised to kill him if he veers too far from his path.

And this has always been Ja'far's role in the series. He is Sinbad's first and most loyal supporter but also his harshest critic. Ja'far, who grew up without any sense of morality, serves as Sinbad's conscious. It's what I love most about their relationship. But all of that seems to disappear at the end of the series. Sinbad becomes the corrupt capitalist dictator and Ja'far his secretary.

Not to mention that when the whole 'mind control' thing happens and we find out that people who were formally fallen are immune, Ja'far was such an obvious choice to lead the main group in their siege on Godbad, to be the guide that shows them the way to victory. He would have been immune bc of his status was a Black Djinn host and also would have been able to kind of fulfill his promise of killing Sinbad until he gets back on course. I cannot explain the absolute jawdrop that transcended the fandom when the final player was revealed to be Whatshisfuck from Reim. People were rioting and fleeing the fandom en masse when the final arc was coming out, it was Not Good.

I love Ja'far as a character and Magi had such a strong play at moral ambiguity and the ethics of global politics and I think a lot of that was lost in the final arc in favor of a shounen typical, he gets the girl and defeats the Big Evil ending and I will forever be bitter about it. Like at one point I wrote out my 'if i was in charge' ending lmao. The last scene of Ja'far standing in Sindria, saying that he's waiting for Sinbad's return was heartbreaking.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In a word, human life is more governed by fortune than by reason; is to be regarded more as a dull pastime than as a serious occupation; and is more influenced by particular humour, than by general principles.

David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary

#philosophy#quotes#David Hume#Essays Moral Political and Literary#life#luck#chance#fortune#reason#rationality

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catharine MacKinnon speaks on the work of Andrea Dworkin

This speech was given by Catharine A. MacKinnon at the Andrea Dworkin Commemorative Conference, April 7, 2006. This original transcript was prepared by secondwaver (blog now defunct).

Andrea should have been here for this. She would have liked it, or most of it. [laughter in audience]

There’s something awful, in both senses, that is, terrible and awe-inspiring, both, about Andrea’s work having to be my topic, instead of my tool, speaking her words not only to further our work together as they were and we did, for over thirty years, but to speak about it, and about her, as a subject, and in the past tense.

Yet even at the same time, her clarity and her passion and her inspiration to all of us to go further, go deeper, flows through her words.

Her whole theory is amazingly present in each phrase that she used. As Blake saw a whole world in a grain of sand, in each of Andrea’s sentences you can see the whole world the way she saw it.

Andrea Dworkin was a theorist and a writer of genius, an unparalleled speaker and activist, a public intellectual of exceptional breadth and productivity. Her work embraced the last quarter of the twentieth century and spanned fiction, critical works of literature, political analysis in essays and speeches and books, and journalism. Her legacy includes a vivid example of the simultaneity of thinking and activism, and of art and politics. Formally, she was an Enlightenment philosopher, in that she believed in and used reason. She was interested in diginity and equality and morality, and, especially, in freedom. Her contribution as a complex humanist was to apply all of this to women, and that changed everything.

An original thinker and literary artist, Andrea saw society ordered by power and the status excrescences of its variations animated by the sexual. She pioneered understanding the social construction of sexuality, and the sexual construction of the social, long before academics dared touch this third rail of social life.

In talking about The Story of O, a book of S/M pornography, in her book, Woman Hating, she says, “The Story of O claims to define epistomologically what a woman is.” She saw O as “a book of astounding political significance.”

Largely overlooked as an intellectual in her own time, she mapped social life before the postmodernists did, finding fairy tales and pornography to be maps for women’s oppression. She wrote about humiliation and fear before study of the emotions was a big academic trend. She analyzed social meaning before hermeneutics really caught on in the scholarly world, asking what pornography means, as for example, in the preface to Pornography, “this is not a book about what should or should not be shown. It is a book about the meaning of what is being shown,” what intercourse means, to men and women, most of all, what freedom for women means.

Her first book, Woman Hating, she “wrote to find out why I am not free, and what I can do to become free.” In her later work, this emphasis on freedom was synthesized with a re-made equality, consistent with and necessary for that freedom.

Her cadences were rhythmic, her use of repetition gaining inevitability and momentum, her suddenly-shifting convergences and metaphors were telling, and often surprising, lyric and antic, fluid and explosive by turns.

Such was her skill as a writer that she gave us almost the experience of pornography without her writing–being–pornography. She could even make intercourse funny, writing of Norman O. Brown speaking of entering women “as if we were lobbies and elevators.” [laughter in audience]

And for undertaking a synchronic reading of her work as a whole and selecting some over-arching themes, I want to reflect for just a minute on what it means that we are here doing this.

The relation between the work and the life is not a new question. But the relation between who Andrea Dworkin was and how her work was socially received is. And it has, as some of us have noticed, shifted noticeably, even dramatically, since the death of her body.

Three months after she died, so unexpectedly, a prominent French political theorist in a Ph.D. exam that I was in, in Paris, referred to her, excoriating the poor student, for eliminating various notables from the bibliography, referred to her as “l’incomparable Andrea Dworkin”–this, in a country that has long refused even to translate her work!

How has the world related Andrea Dworkin’s body to her body of work? Why was it necessary to destroy her credibility and bury her work alive, only now to be resurrected, disinterred, as it were? Why can now she be taken seriously, respected, even read, now that her body is no longer here? Why this is the first conference ever to be held on her work is one side of the coin of the question of why there never was one when she was alive. Her work is as alive now as it ever was, as challenging, threatening, illuminating, inspiring. Maybe it is that she can no longer tell us that we’re wrong, but don’t bet on it. Or maybe if you engage her work while she’s alive you further her mission, and we can’t have that, now, can we?

But why was respecting her and taking her work seriously such a risk? Why were the people who did it considered brave? As the quintessential scholar of the hell of women’s embodiment in social space, Andrea’s relation to her work is posed by, as well as in, this conference. Her work guides us to pursue this question, I think, as one of stigma. Stigma is what has kept people from reading Andrea Dworkin’s work, especially in the academy, where, I must note, people are not noted for their courage. That stigma has been sexual, due to her public identification as a woman with women, including lesbian women, especially as a sexually abused woman publicly identified with sexually violated women–in particular, the raped and the prostituted among us.

Being marked by sexuality, is, in her analysis, the stigma of being female, analyzed by Andrea in greatest depth in Intercourse, a work of literary and political criticism, a work of how men imagine and construct sexual intercourse when they can have it any way they want it, as they can, in fiction. It is a work of criticism of literature, that is at the same time a trenchant and visionary work of social criticism, her most distorted, I would say, a signal honor in a crowded field, published in 1987, at, as John and I were saying, the height of her powers. Of Elma, in Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke, she wrote: “This being marked by sexuality requires a cold capacity to use, and a pitiful vulnerability that comes from having been used, or a pitiful vulnerability that comes from something lost or unattainable, love, or innocence, or hope, or possibility. Being stigmatized by sex,” she wrote, “is being marked by its meaning, in a human life of loneliness and imperfection where some pain is indelible.”

If the stigma of being a woman is the stigma of the body sexually violated, it lessens some when you die. That, girls, is the good news! [laughter in audience] Before now, we have had to be kept from reading Andrea Dworkin’s work, and were, by the living, breathing existence of her sexualized body attached to it, thereby, that work was sexualized. We had to be kept from holding a violated woman’s body in our hands and having her speak to us what she knows. Especially, we had to be kept from knowing in-depth, up close, and personal, that for women, having a body means having a sexuality attributed to you, the sexuality, specifically, of being a sexual thing for use, and from knowing that the need to be fucked in order to see and value ourselves as female means living within a political system that is pervasive, cultural, organized, institutionalized, unnatural, and unnecessary. Cutting to the quick of all of this, with her customary conciseness, Andrea always said she would be rich and famous when she was dead.

Now, Andrea’s great subject is the status and treatment of women, as has been said, focusing on violence against women, as central to depriving women of freedom.

Andrea’s method was predicated on the lived, visceral body experience that women have of our social status. She mined her life, particularly, in her work, knowing what she wrote from experience. Her driving force was rage and outrage, unapologetic critique, unbridled, passionate, truth-telling. Her sensibility was tenderness, kindness, and love. Her aesthetic is political–political in method, that is, you know it’s true because it happened to you, political in voice–clear, direct, no writing for passive readers, as John noted, and no talking down to anyone.

In the rhythms you can feel her breathing. Here is a woman talking to a publisher who is trying to get her to have sex with him. Essentially, this is a woman being sexually harassed. It is from Ice and Fire.

“I want, I say, to be treated a certain way, I say, I want, I say, to be treated like a human being, I say, and he, weeping, calls my name and says, please, begging me in the silence, not to say another word, because his heart is tearing open, please, he says, calling my name. I want, I say, to be treated, I say, I want, I say, to be treated with respect, I say, as if, I say, I have, I say, a right, I say, to do what I want to do, I say, because, I say, I am smart, and I have written, and I am good, and I do good work, and I am a good writer, and I have published. And I want, I say, to be treated, I say, like someone, I say, like a human being, I say, who has done something. I say, like that, I say, not like a whore. Not like a whore, I say, not any more. And I say to him, seriously, some day I will die from this, just from this, just from being treated like a whore, nothing else. I will die from it and he says, dryly, with a certain self-evident truth on his side, you will probably die from pneumonia, actually.”

Her writing is new; this is a new voice in literature. It has new forms; it’s full of new ideas, in part because the reality she wrote, like her, was submerged and ignored. But she was interested in all the classical questions of western philosophy–method, reality, consciousness, meaning, freedom, equality, especially the relation of thought to world, and the connections between social order and human action.

She created new concepts: moral intelligence, scapegoat, woman hating, not quite the same as misogyny, gynocide, gave new meaning to the term possession. She was a profound moral philosopher, and she gave new juice to old concepts like dignity, honor, and cruelty.

But I’m going to do a reading now, today, of her as a political philosopher, a specifically intellectual reading of her work in terms of these questions. Which is not how she wrote it to be read, actually. But she certainly knew what she was doing in these terms. She did not use the word method, but she had one, and she knew it. She observed in her book Pornography: “Women have been taught, that, for us, the earth is flat, and that if we venture out we will fall off the edge. Some of us have ventured out, nevertheless, and so far, we have not fallen off.”

In the afterward of Woman Hating, she said this: “One can be excited about ideas, without changing at all. One can think about ideas, talk about ideas, without changing at all. People are willing to think about many things. What people refuse to do, or are not permitted to do, or resist doing, is to change the way they think.” She knew thinking had a way, and that she had a way of thinking, and she wrote to change the way people thought.

Central to all her work was a metaphysical distinction between what she once termed truth and reality. While the system of gender polarity is real, it is not true.” The polarity of the sexes is a reality because reality is social. Equality of the sexes is true, but social reality is not based on it, but instead on a model that is not true, that is, that the sexes are bipolar, discrete, and opposite–some of us with little, tiny feet. For example, “we are living imprisoned inside a pernicious delusion, a delusion on which all reality, as we know it, is predicated.”

And, then, similarly, on the relation actually between sex and gender–not called that–but check it out: “Foot binding did not emphasize the differences between men and women, it created them, and they were then perpetuated in the name of morality.”

She also said we “need to destroy the phallic identity in men, and masochistic non-identity in women.” Now, it is not that she thought all reality was only an idea, as in classical idealism or only a psychology or an identity in the internal sense. She analyzed material reality and ideas as equally, and reciprocally, even circularly determinative. Of reality, she wrote this: “Men have asked over the centuries a question, that, in their hands, ironically, becomes abstract: ‘What is reality?’ They have written complicated volumes on this question. The woman who was a battered wife and has escaped knows the answer.” Philosophers, take note (is my note here): “Reality is when something is happening to you, and you know it, and can say it, and when you say it, other people understand what you mean and believe you. That is reality, and the battered wife, imprisoned alone in a nightmare that is happening to her has lost it, and can not find it anywhere. A fist in your face is not just the idea of a fist in your face. Reality is relational, and that relation is unequal and social.”

She also wrote explicitly of the relation between the ideational and the material in women’s status, without using specifically those words. That is, both have to be there, and both are there. In Right Wing Women, her 1978 book, the most extended analysis of women’s status and of feminism together, the elements and preconditions of both, she said this: “It does not matter whether prostitution is perceived as the surface condition, with pornography hidden in the deepest recesses of the psyche, or whether pornography is perceived as the surface condition, with prostitution being its wider, more important, hidden base, the largely unacknowledged sexual economic necessity of women. Each has to be understood as intrinsically part of the condition of women, pornography being what women are, prostitution being what women do, and the circle of crimes–these are the crimes against women, rape, battering, incest, and so on, that she discussed–being what women are for.”

The resulting “female metaphysics” under male dominance means that rape, battery, economic and reproductive exploitation “define the condition of women correctly, in accordance with what women are, and what women do,” correctly meaning consistently and accurately, within the existing system. She also said you can’t be a feminist and support any element of this model, including “so-called feminists who indulge in using the label but evading the substance.”

Her identification with women made her especially brilliant at seeing how women’s views are reflected in their material circumstances, hence, were rational, in that sense, including in her devastating portrayal of the academic, not-Andrea, so-called feminist woman who begins and ends Mercy, one of her novels, having been sexually abused, actually, this not-Andrea woman with the arch voice, siding with abstraction, with power, and with distance.

Right wing women, she shows in her book of the same name, also side with male power, because it is powerful, and reject feminism because women are powerless, in the hope, and on the bet, that male protection is a better deal than feminists’ resistance and struggle for change. It is, in that sense, a rational choice, meaning a direct reflection of their circumstances, which isn’t to say that it’s in their long-term interest.

She saw, always, how what women think and do makes sense in light of the realities of male power. As she put about right wing women, “the tragedy is that women so committed to survival can not recognize that they are committing suicide.”

The right–this is part of her deep analysis of religious fundamentalism–gives women form, shelter, safety, rules, and love. This complex and respecting analysis completely outdistances any analysis of false consciousness.

Similarly, in Intercourse, which I am going to have to discuss, this part, she wrote complexly of what it meant that Joan of Arc was a virgin. Probably not literally, she said, but because she carried herself with the dignity of the nonpenetrated, i.e. as a man, and her dressing as a man meant noncompliance with her inferior/female status, for which the Inquisition killed her. Joan wore men’s clothes, not to flout convention, or to make a statement about women’s status, or to portray dignity (performists take note), but because she’d been raped in prison. All she had to do was say–this is Joan–that she would not wear men’s clothes, and they would let her go free. Andrea says, “she was a woman who was raped and beaten and did not care if she died. That indifference is a consequence of rape, not transvestism.”

A new concept of ideology as sexual was proposed by Andrea in the book, Pornography: Men Possessing Women. Pornography is analyzed as male ideology, for its meaning and its dynamics. The concrete harms of pornography weren’t, then, its central topic. All the evidence of that was to come. But Andrea notes that “with the technologically advanced methods of graphic depiction, real women are required for the depiction, as such, to exist.”

In asking what it means, she said this: “the fact that pornography is widely believed to be sexual representations or depictions of sex emphasizes only that the valuation of women as low whores is widespread, and that the sexuality of women is perceived as low and whorish in itself. She says, “The fact that pornography is widely believed to be depictions of the erotic means only that the debasing of women is held to be the real pleasure of sex, and it also embodies and exploits, sells and promotes the idea that ‘female sexuality is dirty.’

So how do you go from seeing to being pornography, from buying a woman in pornography to owning her, from owning pictures of her to owning her, you might be wondering. She says this: “Male sexual domination is a material system with an ideology and a metaphysics. The metaphysics of male sexual domination is that women are whores. The sexual colonization of women’s bodies is a material reality.” This ideology is effectuated sexually, a level of belief and experience never before analyzed as political and gendered in the way she did.

Now on the subject of freedom, her core concern. She notes in her piece, “Violence against Women: It Breaks the Heart, Also the Bones,” “Our abuse has become a standard of freedom, the meaning of freedom, the requisite for freedom throughout much of the western world.” She goes on to say, “as to pornography, the uses of women in pornography are considered liberating.”

The subject of Intercourse, specifically, is what freedom means for women, precisely, how it is denied by the inferiority imposed and the occupation effected thereby, “destroying in women the will to political freedom, destroying the love of freedom itself,” when it takes place under conditions of force, fear, and inequality.

She says, ” to want freedom is to want not only what men have but also what men are. This is male identification as militance, not feminine submission. It is deviant, complex.” This becomes something she terms “the new virginity,” or what might be called the new freedom. “Believing that sex is freedom,” she says, intercourse needs blood, “to count as a sex act in a world excited by sadomasochism, bored by the dull thud-thud of the literal fuck. Blood-letting of sex, a so-called freedom, exercised in alienation, cruelty and despair, trivial and decadent, proud, foolish, liars, we are free.”

This analysis converged her thinking on equality, which underwent a progression over her life. In Our Blood, the piece renouncing sexual equality, she rejected equality, which she understood there as “exchanging the male role for the female role.” There was no freedom or justice in it, an accurate understanding of the mainstream view of equality. Over time, she reclaimed and redefined equality. In “Against the Male Flood” she said, “equality is a practice; it is an action; it is a way of life. Equality is what we want, and we are going to get it.”

To clarify the relation between her freedom and the equality that she redefined, she said this (this is again in her piece for the Irish women, “Violence Against Women: It Breaks the Heart, Also the Bones”)–check this out–: “What we want to win is called freedom or justice when those being systematically hurt are not women. We call it equality because our enemies are family.”

Even with family, Andrea took no prisoners, a paradoxical result of her passionate humanism. She says this in “I Want a Twenty-Four Hour Truce During Which There Is No Rape,” a talk to five hundred men in 1983: “Have you ever wondered why we are not just in armed combat against you? It’s not because there’s a shortage of kitchen knives in this country. It’s because we believe in your humanity, against all the evidence.”

Now, her legacy leaves us a lot to do. We can learn from the richness of her thirteen volumes, we can read her work closely, figure out how her writing was so singularly effective, and we can effectuate it. We can respond to the challenges of her questions, and be changed by her interventions and fearless probing of the structures and forces and people that rule our lives, denied by most people, a denial she also analyzed.

But in the academy, you know, whole theses could be written exploring sentences chosen virtually at random, that are ripe with possibilities, such as this: “any violation of a woman’s body can become sex for men. This is the essential truth of pornography.”

Or this: “in pornography, everything means something,” overwhelmingly ignored by massive departments of Media Studies and Communications, except for a tiny branch of largely social psychologists. Or this one, an analysis of social life in gendered terms: “Money is one instrument of male force. Poverty is humiliating, and, therefore, a feminizing experience.” Now, envision an economics where the laws of motion of sexuality socially are as well understood as the laws of motion of money are understood today, and the relation between the two of them.

Or this. Racism has always been central to her analysis, as it was in Pornography: “the sexualization of race within a racist system is a prime purpose and consequence of pornography.” And she talked about depicting women by sexualizing their skin, thus sexualizing the abuse, sexually devaluing black skin in racist America by perceiving it as a sex organ.

In Scapegoat she took this entire analysis to a whole deeper and higher level simultaneously showing what a gendered analysis of racism would look like in application. Try this: “While Nazism was a male event, Auschwitz might be called a female event, built on a primal antagonism to the bodies of women, an antagonism that included sadistic medical experiments.” In Scapegoat she also said this: “Hitler tried to make Jews as foul and expendible as prostitutes already were, as inhuman as prostitutes were already taken to be.” All of this can be taken up, unpacked, deeply considered, extended, gone further with.

Andrea wanted a day without rape. She said, “I want to experience just one day of real freedom before I die.” And that was the day without rape. She didn’t get it. She told the story of her own life in many ways in her work, over and over again. In one meditation, in Ice and Fire, turning over and over Kafka’s referring to coitis as “punishment for the happiness of being together,”–that’s a quote from him–Andrea writes this: “Coitis is punishment. I write down everything I know, over some years. I publish. I have become a feminist, not the fun kind. Coitis is punishment, I say. It is hard to publish. I am a feminist, not the fun kind. Life gets hard. Coitis is not the only punishment. I write. I love solitude. Or, slowly, I would die. I do not die.”