#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

Text

Altuzarra s/s 2024 rtw

Creative Director Joseph Altuzarra

Fashion Editor/Stylist Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

Photographer Armando Grillo

Newest Cool

#newestcool#newest cool#high end bag#high end bags#bag designer#bag designers#runway bag#luxury bag#bag heaven#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson#altuzarra#Joseph altuzarra#ss2024#ss24#ss 2024#ss 24#spring/summer 2024#spring summer 2024#ready to wear collection#runway details#runway style#runway looks#runway collection

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the Break in Senegal

Paloma Elsesser joins Dakar's merry band of surfers, in this season's boldest prints. Photographed by Eddie Wrey. Fashion Editor: Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vogue US June 2023. Margot Robbie wears shirt & shoes, Maison Margiela by John Galliano, Co-Ed Collection 2023. Photographer Ethan James Green, styled by Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

#Margot Robbie#Maison Margiela#Margiela#Maison Margiela by John Galliano#John Galliano#Galliano#Ethan James Green#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson#fashion#fashion shoot#editorial#Vogue#Vogue US#American Vogue#actor#actress#fashion photography

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

moschino ss24

#moschino#milan#fashion week#ss24#moschino ss24#gabriella karefa-johnson#fashion#couture#lace#accessories

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

from Play On!

Akon Changkou by Campbell Addy

styled by Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

for Vogue, November 2022

16 notes

·

View notes

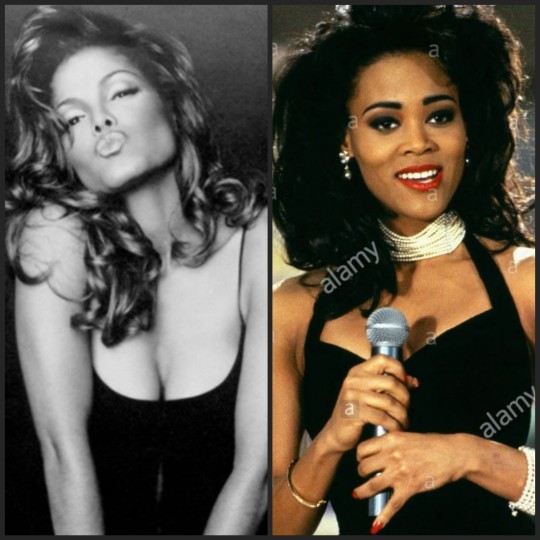

Text

Serena Williams for the September 2022 issue of Vogue Magazine.

Photography by Luis Alberto Rodriguez

Styled by Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

gabriella karefa-johnson, met gala 2023

#my fav editor/stylist working right now and always tbh!!!!#and she looks so good!!!!#gabriella karefa-johnson#coach#fashion#met gala

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Tlayacapan#Nadine Ijewere#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson#Marni#Bode#Y/Project#Act n°1#Dries Van Noten#Marianne Williams#Edward Lampley#Grace Ahn#Licett Morillo#Huitzili Espinosa#Samuel Guerrero#Victoria Serrano#Garage#Garage Magazine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

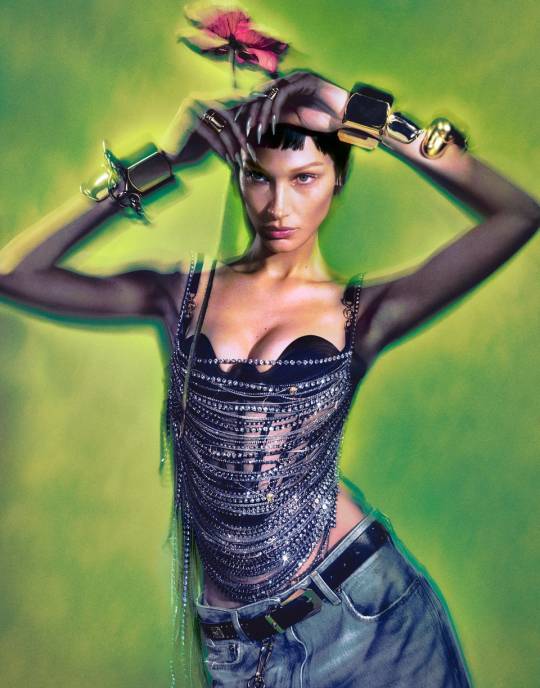

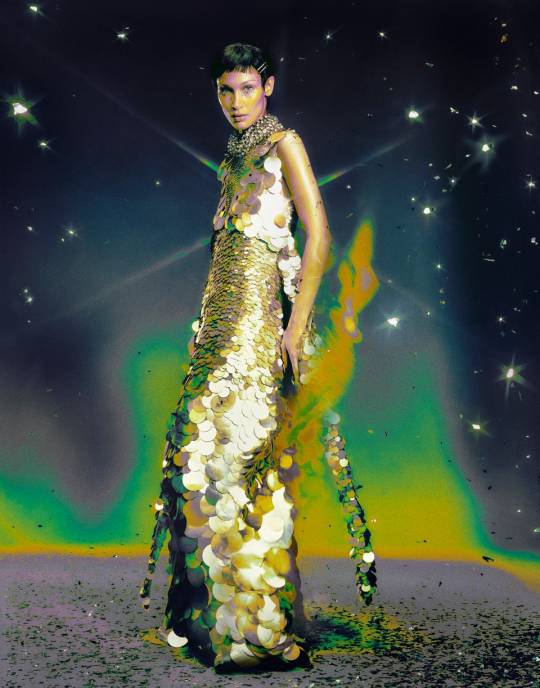

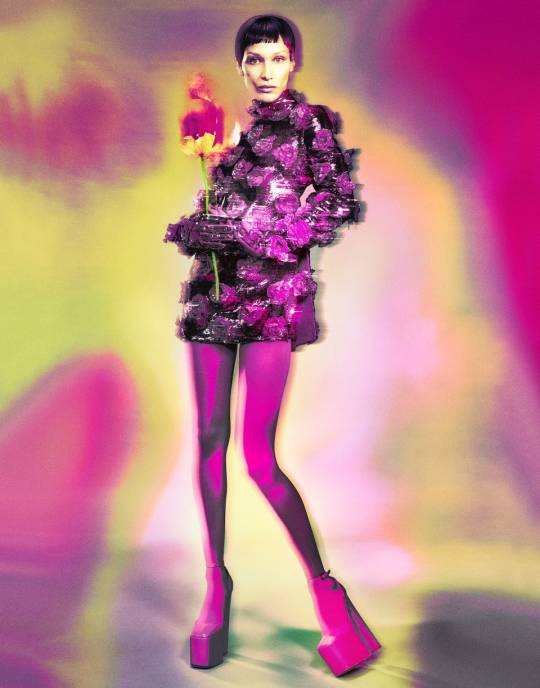

Bella Hadid by Elizaveta Porodina for Vogue Spain, August 2022

Fashion Editor: Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

Fashion credits

#bella hadid#elizaveta porodina#vogue#fashion photography#editorial#fashion#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson#2022#august 2022#metallic#paillettes#alexander mcqueen#sarah burton#versace#tiffany & co#collina strada#altuzarra#bottega veneta#valentino#vogue spain#vogue espana

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Target partners With Gabriella Karefa-Johnson for "Future Collective"

Target partners with Gabriella Karefa-Johnson for “Future Collective”. This partnership will be bringing the girls spring fashions. Keep reading for more details on the new partnership.

(more…) “”

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Margot Robbie x Vogue Magazine

#margot robbie#vogue magazine#beauty#ethan james green#photography#gabriella karefa johnson#style#barbie 2023#barbie#pro-royalty

892 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful People 👑

jadecargill:

A day late but late is better than never. Happy International Women’s Day! 🩷💚 @wwe

theestallion:

🍄😻💞

kellyrowland:

🖤🤎🖤

victoriamonet:

Thank you @donatella_versace for having me at such a beautiful celebration of Versace icons! I felt so beautiful in my Satin Blue Medusa 95 @versace gown 🩵 Styled by @kollincarter assisted by @juanmarioortiz_

Glam: @ernestocasillas

Hair: @iamdavontae

📸 @mr_dadams

beyxkelly:

#oscars Weekend with KellyKelly 🍫😘 @kellyrowland via: @wilfordlenov

thedaniellebrooks:

🖤One more day… 🖤

OSCARS

americanblackfimfestival:

2024 ABFF Honors Excellence In The Arts Award Recipient @tarajiphenson 😍🤩

📸: @cire.capture

Studio Designed By👩🏾🎨: @detrapalmoredesigns #ABFFHonors2024 #ABFF2024 #TarajiPHenson #ABFFHonors

#janet jackson#robin givens#kelly rowland#megan thee stallion#jade cargill#victoria monét#donatella versace#tim weatherspoon#coco jones#danielle brooks#gabriella karefa johnson#taraji p. henson#chlöe bailey#beautiful people

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Florence Pugh by Colin Dodgson, styling Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

75 notes

·

View notes

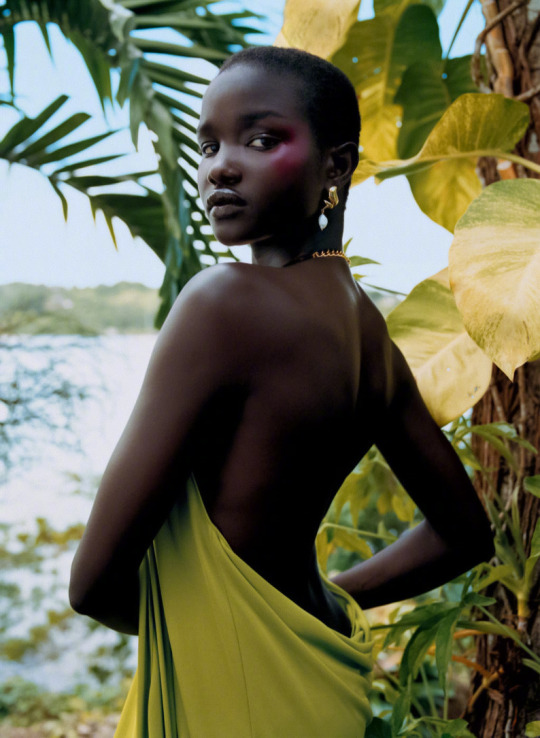

Photo

Akon Changkou, photographed by Nadine Ijewere and styled by Gabriella Karefa-Johnson for Vogue US April 2023

#Akon Changkou#Nadine Ijewere#Gabriella Karefa-Johnson#fashion#fashion shoot#editorial#Vogue#Vogue US#American Vogue#model#style#nature#green#fashion photography

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on “Diversity”.

Following the brutal murder of George Floyd in 2020 – a spark that ignited riots in protest of police brutality and, in turn, the inequality that Black people face on a daily basis – fashion was forced to reckon with its own shortcomings, as an industry that has long neglected people of colour across the board.

Amid a sea of black squares – allegedly posted in solidarity with Black people, though you’d struggle to find one to corroborate this – brands and publications scrambled to atone, not knowing whether to apologise for the existence of systemic racism or fashion’s part in upholding it (see: here, here, and here). All the while, promises were made for a better, more inclusive future.

Yet, almost three years later, all is quiet on the fashion front with diversity and inclusion seemingly no longer a priority – the industry’s short attention span quickly moving on now it’s no longer en vogue.

Last June, The British Fashion Council released its ‘Diversity and Inclusion in the Fashion Industry’ report, revealing that only half (51 per cent) of the 100 companies interviewed had implemented D&I initiatives, with even fewer dedicating budget towards those efforts. It’s disappointing, even more so to learn that those hired to implement D&I strategies often leave their roles swiftly as has been the case at Gucci and Nike.

The report is reflective of fashion’s attitude towards diversity – with mostly white voices echoing familiar platitudes around ‘learning’ and ‘growing’, reluctant in committing to tangible targets. While quantifying representation isn’t necessarily helpful in moving towards genuine diversity and inclusion, fashion’s longstanding ability to champion exclusivity and use ‘taste’ and networking culture as gatekeeping tools warrants numerical evidence to highlight its abysmal efforts.

Though, even this in itself is a troublesome task as the New York Times found in its own 2021 report on Black representation in fashion, with several European companies citing legislation such as GDPR as an obstruction for gathering and sharing data on their failings. As the BFC found, even after 2020’s demand for diversity, people of colour currently make up only 5 per cent of employees at a direct report level – hindering any growth in representation in leadership roles.

instagram

Until now, Black creatives have had to go it alone, relying on their excellence to be noticed – shining so bright, it’s impossible to dim. The door, now slightly ajar, has made way for a number of rising stars, more often than not ‘firsts’ in their roles or achieving feats that previously weren’t attainable for people of colour.

From Gabriella Karefa-Johnson (the first and only Black woman to style a Vogue cover) to Tyler Mitchell (the first Black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover), others include Elle UK’s Kenya Hunt, The Cut’s Lindsay Peoples, Harper’s Bazaar’s Samira Nasr, and Rafael Pavarotti.

Ib Kamara best exemplifies this calibre of creative – a talent so in-demand, it’s a wonder when he sleeps, juggling roles as Dazed’s editor-in-chief, Off-White’s art and image director, as well as working as a freelance stylist for Chanel, Vogue, and H&M.

While working twice as hard to get half as far is a familiar mantra for people of colour, the current makeup of the industry sets the bar for them at an almost inhuman level, demanding the very, very best out of them simply to be seen – forgoing the mediocrity sometimes afforded to our white peers. In failing to nurture and recognise talents beyond the brightest and best – i.e. people who were always destined for success on their own volition – brands and publications alike posture as pioneers after simultaneously (read: lazily) box-ticking relevance and representation with such hires.

Yet in some instances, ‘excellence’ isn’t even enough. Pharrell Williams’ recent appointment as Louis Vuitton’s Men’s creative director – succeeding Virgil Abloh (another first) – came as something of a surprise, quelling speculation that the role might instead go to designers such as Martine Rose, Grace Wales Bonner, or Bianca Saunders.

The decision makes sense given the evolving role of a creative director today, with Williams likely chosen for his celebrity status and proximity to the community that Abloh fostered during his tenure, but it’s easy to see why it’s a contentious one. Particularly so, in the case of Wales Bonner, the winner of the LVMH Prize in 2016 – receiving not only a grant of €300,000 to support her business, but more importantly, mentoring from LVMH executives. If not to induct a new generation of designers into the fold, what longevity does the LVMH Prize hope to offer its winners?

Let’s say you’re one of the driven Black creatives who has broken through the proverbial glass ceiling. Surely now, all obstacles limiting your success have been eliminated?

Apparently not.

In the past month, Law Roach shocked the industry with a (now-deleted) announcement of his retirement on Instagram. Arguably the leading celebrity stylist at the height of his career – counting Hunter Schafer, Megan Thee Stallion, and Anne Hathaway among his regular clients, as well as solidifying Zendaya as a fashion icon – netizens speculated that the decision was a cry for attention, prompted by a seating mishap at Louis Vuitton’s Autumn/Winter 2023 show.

Clarifying in an interview with The Cut, the stylist reflected on the industry’s gatekeepers and the hoops he’s still made to jump through 14 years into his career. Even in his candour, it felt as if something was being left unsaid, alluding to the complexity people of colour have in trying to justify the racism they experience to people who will never understand its complexities.

Similarly, Hood By Air co-founder Shayne Oliver recently opened up for the first time about his experience as Helmut Lang’s guest designer in an interview with 032c’s Brenda Weischer. Reflecting on his celebrated single season following the brand’s revival in 2017, Oliver shared his encounters with the brand’s executives. “It was the biggest show they’ve had in 10 years, and the very next day I get notified that I’m not welcome in the showroom in Paris,” he explained.

In examining these somewhat inconspicuous decision-makers more closely, it becomes clearer how people of colour in seemingly senior positions can still find their voices unheard. “The collective intelligence that comes from diverse points of view and the richness of different experiences are crucial to the future of our organisation,” asserted Kering chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault in June 2020 after Emma Watson, Jean Liu, and Tidjane Thiam were announced as new Board members for the conglomerate. Liu has since resigned and Thiam’s contract completes at the end of 2023, bringing the number of people of colour on the Board back down to zero.

The same is true at LVMH [Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi, Givenchy, Stella McCartney, Loewe, Marc Jacobs, Kenzo, Celine, Off-White], OTB [Diesel, DSquared2, Maison Margiela, MM6, Marni], and Puig [Paco Rabanne, Jean Paul Gaultier, Dries Van Noten, Nina Ricci] while Richemont [Azzedine Alaïa, Chloé, Dunhill] and the Prada group [Prada, Miu Miu] have a single person of colour on their boards, both hired after June 2020. As it stands, none of the above brands have people of colour in the role of CEO.

In 2020, WWD reported on the three Black CEOs in fashion: Virgil Abloh, Jide Zeitlin at Tapestry [Coach, Kate Spade, Stuart Weitzman], and Sean John’s Jeff Tweedy. In the three years since, this number has dropped to zero, following the passing of Abloh, while Zeitlin resigned for a misconduct allegation and Tweedy has left fashion entirely. Interestingly, Chanel is currently the only major house with a person of colour as CEO, after hiring Leena Nair in January 2022.

As the only voice in the room, people of colour often struggle to bring about the radical change needed for true diversity and representation. As Stella Jean found with Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana, despite her continued efforts to bring diversity to Milan Fashion Week’s overwhelmingly white schedule, the arduous battle ended with alleged sabotage and a hunger strike. In response, the CNMI argued their efforts were only possible because of “extraordinary fundings, due to the COVID pandemic”, once again highlighting the reticence to dedicate resources towards D&I and the lack of effort without it.

instagram

2020’s focus on diversity also saw an immediate uptick in Black content – from i-D’s Up + Rising campaign to Hearst’s Black Culture Summit – inviting new writers, photographers, stylists, and more to contribute to titles previously out of reach, though little has changed within most of the teams themselves.

Currently, there are (at least) 16 fashion publications across the UK and US with all-white editorial mastheads – excluding ‘at large’ roles, which people of colour seem more likely to hold since 2020. Extend this to publications with only a single person of colour, often, but not always in the most junior position, and the figure almost doubles.

Unsurprisingly on the flip side, publications with people of colour in the editor-in-chief role – in the UK, British Vogue, Dazed, Elle, Perfect, and Wonderland – translates into more broadly diverse teams inclusive of intersectional identities.

Meanwhile, POC-led publications like Justsmile and Boy.Brother.Friend are stunted in their growth, with both titles appearing to only receive brand support from Burberry during Riccardo Tisci’s tenure as chief creative officer. Though not exclusively a fashion magazine, gal-dem’s recent announcement that it would be shuttering after eight years further highlights the difficulties in creating and maintaining spaces specifically for people of colour.

With limited opportunities in-house and all-white mastheads only commissioning Black freelancers for stories that have a proximity to Blackness – though in some cases, not even then – they’re simultaneously pigeonholed while fighting for the same jobs. A friend, who was recently commissioned and ghosted for a Highsnobiety cover opportunity later found out that (at least) two other women of colour were hired for the same story, the two unsuccessful parties only finding out upon publishing. While this can often be part and parcel of the job, it’s hard to ignore the impact it has on people of colour in instances like this when they’re specifically being hired because of their race due to the nature of the story.

instagram

With the power to bring about change in spaces we rarely occupy out of our hands, it’s up to those in positions of power to go above and beyond in order to rectify previous wrongs.

Amid 2020’s reckoning, Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour apologised via an internal memo in which she admitted her own shortcomings. “I want to say plainly that I know Vogue has not found enough ways to elevate and give space to Black editors, writers, photographers, designers and other creators,” it read in part. While some speculated that this longstanding oversight would signal the end of her 32-year tenure at the helm of the magazine, six months later she was promoted to become Condé Nast’s global chief content editor.

If we’re to see Vogue as the industry standard, Wintour’s efforts since should be heavily scrutinised, a sentiment she agrees with. “I will take full responsibility if the next time you and I speak, there isn't a sense that change has come or is being accomplished, or at least it is moving forward,” she explained to the Washington Post’s Robin Givhan. So, what has been accomplished in the three years since then?

In September 2020, Yashica Olden was hired as Condé Nast’s first global chief diversity and inclusion officer – overseeing a roadmap towards an inclusive future at the group’s various publications [Vogue, Allure, Glamour, GQ, Vanity Fair, etc]. However, a closer look at the three annual Diversity and Inclusion reports for 2020, 2021, and 2022 reveals that the initial marginal growth – +4 per cent total people of colour from 2020-2021 – has since stagnated.

For Black editorial staff specifically, there was an increase of 2 per cent from 2020-2021 with no increase after that, while representation among senior staff has remained the same. In fact, the only constant growth (+5 per cent 2020-2021, +4 per cent 2021-2022) has been for people of colour in the editor-in-chief role, though former Teen Vogue editor (note: not editor-in-chief) Elaine Welteroth shared in her memoir More Than Enough her thorny experiences – alleging her role had different parameters to her white predecessor and that the promotion came with an insulting, non-negotiable pay rise delivered by Wintour herself.

In Condé Nast’s initial D&I report, a commitment was also made to “support diversity among freelancers and contributors, including photographers”, and while there has been a concerted effort since 2020 to bring in new Black photographers who haven’t previously contributed to the publication – names such as Campbell Addy, Joshua Woods, Myles Loftin, and John Edmonds – Asian photographers are still severely overlooked and for almost all, this has been a one-time opportunity.

The same is true for the publication’s hallowed cover. Besides Tyler Mitchell – who was the first Black photographer to achieve the honour in Vogue’s 126-year history – the others who have since joined the hall of fame can be counted on a single hand. That goes for stylists too, other than Gabriella Karefa-Johnson who has since become the title’s global contributing fashion editor-at-large. Comparably, Annie Leibovitz has nine additional covers under her belt, five of which feature Black talent – despite ongoing criticisms of her inability to capture their beauty. At the time of publishing, Vogue has released four issues in 2023, none of which have covers photographed by a person of colour.

In addition to diversifying content, publications have doubled down on their coverage of racism – though it’s difficult to ignore the hypocrisy around the selectiveness of this. While Vogue is not alone, its response to Kanye West’s YZYS9 show best illustrates this.

Initially commissioning Raven Smith to (rightfully) call out the ‘White Lives Matter’ t-shirts, there were also rumours of a face-to-face interaction with West and Karefa-Johnson – following his tirade against the stylist on Instagram – filmed by Baz Luhrman. Later, Wintour and Vogue officially cut ties with him, following his anti-Semitic comments, though it remains to be seen if he will be given the same grace as John Galliano in years to come.

Meanwhile, Dolce & Gabbana continues to dodge cancel culture and is still reviewed each season and given prominent real estate space at the publication – its most recent cover in December 2021, worn by Sarah Jessica Parker. A friendly reminder that the brand’s racism isn’t just limited to a questionable campaign which led to the cancellation of its Shanghai show in 2018. There are also racist DMs, ‘Slave’ sandals (2016), posing with partygoers dressed as minstrels at a ‘Disco Africa’ party (2013), and a Spring/Summer 2013 collection filled with Mammy iconography and zero Black models (2012).

With publications and celebrities continuing to support the brand despite this, the consequences are twofold. For people of colour, it highlights that money will always speak louder than their condemnations. More worryingly, for those who should be fearful of the impact of being ‘cancelled’ – seemingly the only way to police these kinds of transgressions – they can simply avoid accountability by writing a cheque.

instagram

Now, three years on from 2020’s reckoning, there is an uncomfortable feeling among Black creatives working in fashion that after coming to a shuddering halt, the movement is now regressing – not that you’d be able to tell from your Instagram feed.

While there is little research specifically investigating this – though Quartz says it’s also regressing – scrolling back through various brands’ and publications’ feeds to find the aforementioned 2020 apologies, there appears to be a blanket of Black faces giving the impression of diversity. It’s a technique often implemented on the runway too. TheFashionSpot stopped publishing its seasonal report, but the Autumn/Winter 2022 shows revealed the smallest increase from the previous season since June 2020 – at only 0.6 per cent.

As diversity among models appears to regress, the work available for them becomes even more limited too. Levi’s was recently criticised for its use of AI models to create “a more personal and inclusive shopping experience” instead of simply hiring existing people of colour. Meanwhile, ‘digital supermodels’ like Shudu Gram – created by white photographer Cameron-James Wilson – are tapped for advertorials with brands including Ferragamo and Christian Louboutin.

There’s also something to be said about the way in which Blackness is represented in the imagery we consume. Now, fashion editorials that feature Black models have become homogenised, a combination of brightly coloured backdrops with the saturation dialled up to 100 to highlight their glossy complexion – seemingly taking cue from Rafael Pavarotti. Yet, when there are no discernible differences between images that we perceive as being associated with Black creatives and images that emulate the same aesthetic without including any, we must carefully scrutinise the blind spots that give a false sense of progress.

For Black people, this disparity becomes harder and harder to ignore post-2020. At the recent Autumn/Winter 2023 shows, Gucci’s interim collection was, for the most part, praised by my peers in attendance who lauded the Ford-Michele mash-up of covetable clothes. Admittedly, they were, but days later all I could think about is the fact that when the design team appeared to take their bow (11:38), everybody was white. In contrast, at Sunnei – presented on the same day, hours later – the collection was modelled by its own team, revealing (at least) 3 Black people working at the brand.

When I interviewed Serhat Işık and Benjamin A. Huseby about their Trussardi debut for AnOther, they told me that this lack of representation is sadly commonplace. “We had a visit to the headquarters to meet everyone who worked there,” Huseby recalled, “and we didn’t see a Brown person until the end of the day when the cleaners were coming into the building, which is very typical for a lot of fashion houses – especially in Europe.” Their short stint, reportedly because of budget constraints, is a blow both to POC designers hoping to make their mark at a fashion house – “Five years ago, we probably wouldn't have been appointed to this position,” Işık admitted – but also for any people of colour they opened the door for during their tenure.

instagram

The magnifying lens fashion found itself under in the midst of its reckoning gave me the rare opportunity to directly discuss the lack of diversity at the company I was working for at the time, as well as within the British Fashion Council – a timeline of the latter’s ‘achievements’ since can be viewed here. However, much like the efforts towards the inclusive future that we were promised at the time, the openness towards these conversations seems to have also regressed.

The discussions I had with other people of colour in the lead up to writing and publishing this essay made two things very clear. First, that very little, if anything, has been achieved in moving the dial forward. Perhaps more worryingly, is that people of colour are hesitant, if not afraid, of speaking up about the continuing impacts of systemic racism within fashion for fear of retribution. If you’re a writer, photographer, stylist, graphic designer, publicist, make-up artist, influencer – it doesn’t matter – the ramifications are as pervasive as ever.

Despite this, even now I don’t believe the responsibility of forging the path forward should be squarely on the shoulders of people of colour. If any progress is to be made, we need more white advocates who are willing to listen, support, and use their own voices to amplify this issue – especially when there aren’t any people of colour in the room.

Since 2020, I’ve been repeating the same phrase: ‘Everyone wants to change the world, instead of changing things in their own lane.’ To me this means a few things: What unconscious biases do I have that need investigating? How can I address diversity (or a lack thereof) in my workplace? How can I help amplify the concerns of people of colour? What power do I have to give people of colour (more) opportunities? What opportunities have been offered to me that can be passed on? It’s this line of thinking that has allowed me to investigate and work towards rectifying my own blind spots.

Throughout, I have specifically focused on the way in which Black people, and more widely people of colour, are impacted, but this could just as easily apply to other marginalised groups – people who are trans or gender non-conforming, working class, or disabled etc. Perhaps even more so, given that the absence of these identities within the industry is rarely highlighted in the same way.

Though my optimism in 2020 was sadly short-lived, the sooner we improve representation from the top-down, the sooner we can begin dismantling the systemic issues I’ve outlined, which in turn, will help from the bottom-up by removing obstacles that stop people of colour from pursuing careers in fashion in the first place – an issue I investigated for Dazed back in 2017.

Simply put, if the past three years have taught us anything, it’s that we don’t need more apologies or half-baked promises, we need action.

instagram

While there is still a long, long way to go, I want to end on a positive note, reflecting on the unique perspective that Black creatives can bring to fashion when they’re given both the means and opportunity to thrive.

At a time where we’re constantly bombarded with images, Imruh Asha – stylist and Dazed’s fashion director – manages to cut through the noise with work that is joyous, vibrant, and never fails to bring a smile to my face.

Elsewhere, Lindsay Peoples’ editorial direction for The Cut has transformed an astute platform into one that embodies everything I love about fashion – a balance of playful frivolity and intelligent scrutiny.

Finally, the lasting impact of Virgil Abloh is as pertinent as ever. Though I only had a single opportunity to interview him before his untimely passing, in the time since, I have come across more and more Black talents who have shared their stories of his kindness, compassion, and ardent support of them and others who look like them. While he is no longer here to guide us, his legacy remains, as well as his proposed roadmap to the diverse, inclusive future that we all deserve.

In his words: “I am so proud to have a platform that allows me to target, hire, and work with diverse teams of some of the most talented artists and thinkers to fuel every step of the creative process. We cannot reach an equitable future without first looking critically at how our own ecosystems help or hinder that growth.”

#diversity#inclusion#fashion#vogue#anna wintour#blacklivesmatter#black creatives#kanye west#gabriella karefa johnson#rafael pavarotti#imruh asha#virgil abloh#ib kamara#journalism#fashion journalism#fashion criticism#Instagram

9 notes

·

View notes