#Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi

Photo

Isao Shirasawa, Chishu Ryu, Chieko Higashiyama, Setsuko Hara, Ichiro Sugai, Kuniko Miyake, and Zen Murase in Early Summer (Yasujiro Ozu, 1951)

Cast: Setsuko Hara, Chishu Ryu, Chikage Awashima, Kuniko Miyake, Ichiro Sugai, Chieko Higashiyama, Haruko Sugimura, Kuniko Igawa, Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi. Shuji Sano, Toyo Takahashi, Seiji Miyaguchi. Screenplay: Kogo Noda, Yasujiro Ozu. Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta. Art direction: Tatsuo Hamada. Film editing: Yoshiyasu Hamamura. Music: Senji Ito.

Early Summer is the second of the "seasonal" films made by Yasujiro Ozu in what is now recognized as his peak postwar period. The first was Late Spring (1949), and they were followed by Early Spring (1956), Late Autumn (1960), The End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962). I mention this chiefly because the English-language titles confuse even Ozu's hard-core admirers, among whom I count myself. "Was that Early Summer or The End of Summer?" we find ourselves asking when we're talking about Ozu's films. The confusion is further compounded by the fact that four of them starred the marvelous Setsuko Hara. It also doesn't help that the name of her character in Early Summer is Noriko, which was the name of her characters in Late Spring and Tokyo Story (Ozu, 1953). So we have to remind ourselves that in Early Summer she is Noriko Mamiya, the unmarried 28-year-old daughter of Shukichi (Ichiro Sugai) and Shige Mamiya (Chieko Higashiyama). She lives with them as well as with her brother, Koichi (Chishu Ryu), and sister-in-law, Fumiko (Kuniko Miyake), and their two bratty sons. She also has a well-paying clerical job and a group of old girlfriends from her schooldays. So why does everyone, even her boss, want her to get married? When her boss starts arranging things with an old business friend of his, her family encourages the connection, even though she's never met the man and he's in his early 40s. Noriko has a mind of her own, however, and eventually surprises everyone -- perhaps even herself -- with her decision. It's a comedy-drama in which nothing exciting happens -- even key events like the search for the bratty boys when they decide to run away from home take place mostly off-screen -- but Ozu holds everything in such delicate suspension, allowing us to meditate on the relationships at length, that we get caught up in the everyday lives of the film's huge cast. There are some wonderful scenes between Noriko and her girlfriends, who share the kind of in-jokes that old friends everywhere have. Some of these are lost in translation, but even that reminds us of real life, when we're left out of a group's established routines. And sometimes the subtitles wittily help us out, finding equivalents for the hick accents Noriko and her friend adopt when talking about the possibility of moving from Tokyo to the country. Ozu and co-screenwriter Kogo Noda bring the characters to life in their private moments, as when Shukichi and Shige talk wistfully about the son who remained MIA after the war, or when they see a balloon floating ahead and reflect on how sad the child who lost it must be. No filmmaker had a profounder sense of the inner lives of people in their ordinary routine.

#Early Summer#Yasujiro Ozu#Isao Shirasawa#Chishu Ryu#Chieko Higashiyama#Setsuko Hara#Ichiro Sugai#Kuniko Miyake#Zen Murase

3 notes

·

View notes

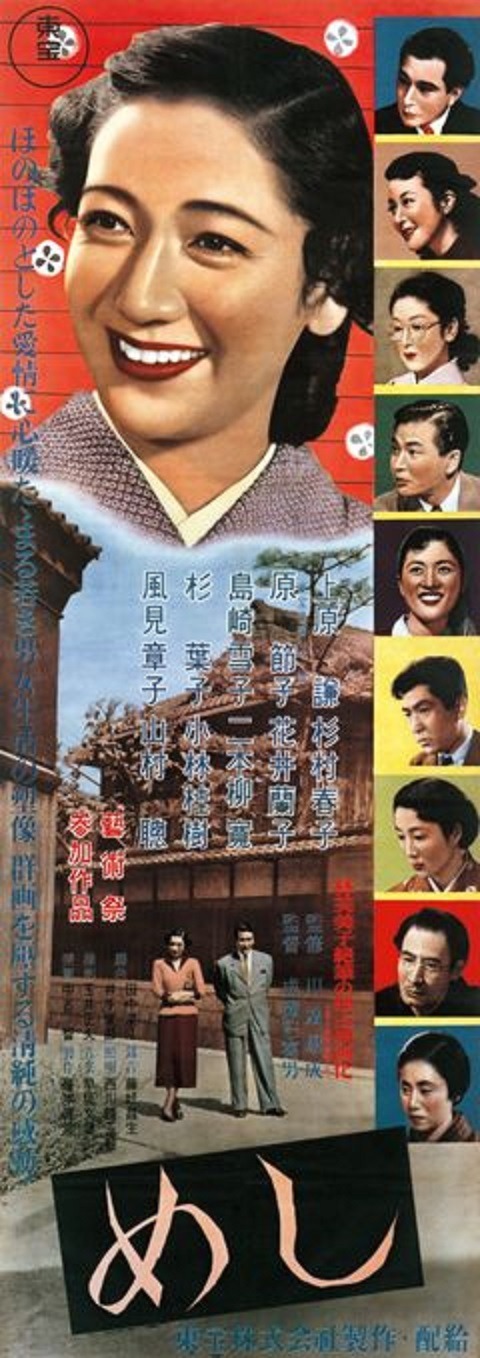

Photo

Setsuko Hara and Ken Uehara in Repast (Mikio Naruse, 1951)

Cast: Setsuko Hara, Ken Uehara, Yukiko Shimazaki, Yoko Sugi, Akiko Kazami, Haruko Sugimura, Ranko Hanai, Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi, Keiju Kobayashi. Screenplay: Toshiro Ide, Sumie Tanaka, Yasunari Kawabata, based on a novel by Fumiko Hayashi. Cinematography: Masao Tamai. Art direction: Satoru Chuko. Music: Fumio Hayasaka.

Repast is one of those beautifully layered films by Mikio Naruse that defy simplistic judgments about the characters. Superficially, it's a story about a failing marriage that tempts you to take sides: Michiyo (Setsuko Hara) and Hatsunosuke (Ken Uehara) have been married long enough that the tenderness has rubbed off of the relationship, and they have no children to provide a distraction from the routine of living together. She suffers the tedium and toil of keeping house, and he comes home from his salaryman's job in an office tired and frustrated. They are scraping by financially, and live in a less than desirable neighborhood. Initially the focus seems to be on the woman's lot -- she's the one we see doing all the lonely work of managing the house, whereas he at least has the opportunity to get out and fraternize with his fellow office workers. And when his lively young niece, Satoko (Yukiko Shimazaki), comes to visit -- actually to escape from family pressure to settle down and get married -- Michiyo finds herself slaving for both her husband and his niece. Eventually, things come to a head and Michiyo goes to Tokyo, taking Satoko back to her parents and leaving Hatsunosuke to fend for himself, which he doesn't do a particularly good job of. But Naruse is careful to let us see his side of things as well, and when Michiyo returns to him -- after making a few steps toward finding a job and leaving him permanently -- it's possible to see this as not a defeat for her so much as an acknowledgement that some remnants of their original affection remain and that she has decided to try to build a more equitable relationship on them. The performances of Setsuko Hara and Ken Uehara, who starred in several other films for Naruse, have that lived-in quality necessary for such a muted and ambivalent conclusion.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Yusuke Kawazu and Miyuki Kuwano in Cruel Story of Youth (Nagisa Oshima, 1960)

Cast: Miyuki Kuwano, Yusuke Kawazu, Yoshiko Kuga, Fumio Watanabe, Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi. Screenplay: Nagisa Oshima. Cinematography: Takashi Kawamata. Music: Riichiro Manabe.

In addition to the shamelessly exploitative title Naked Youth, Cruel Story of Youth has also been released as A Story of the Cruelties of Youth. So is it the story that's cruel or the youth in it? Those who know Japanese can probably tell me which is closer to the original title, Seishun Zankoku Monogotari, but I suspect the ambiguity is intentional. It's a cruel story about cruel young people, with the usual implication that society -- postwar, consumerist, America-influenced Japan -- is to blame for the cruelties inflicted upon and by them. With its hot pops of color and unsparing widescreen closeups, the film puts us uncomfortably close to its young protagonists, Makoto (Miyuki Kuwano) and Kiyoshi (Yusuke Kawazu ). Makoto is just barely out of adolescence -- Kuwano was 18 when the film was made -- but carelessly determined to grow up fast. She hangs out in bars and cadges rides with middle-aged salarymen until the night when one of them decides to take her to a hotel instead of her home. When she refuses, he tries to rape her. But a young passerby intervenes and beats the man, threatening to take him to the police until the man hands over a walletful of money. The next day, Makoto and her rescuer, Kiyoshi, meet up to spend the money together. He's just a bit older -- Kawazu was 25, three years younger than the film's director, Nagisa Oshima -- and over the course of their day together on a river he slaps her around, pushes her into the water and taunts her when she can't swim, and seduces her with his mockery of her inquisitiveness about sex. When he doesn't call her again, she seeks him out and they become lovers. They also become criminals: She goes back to her game of hooking rides with salarymen and he follows them, choosing a moment when the men start to get handsy with Makoto -- sometimes she provokes them to do so -- to beat and rob them. Naturally, things don't get better from here on out, especially after Makoto gets pregnant. We can object to the film's sentimental attempt to redeem Kiyoshi, who starts out as an abusive young thug but is transformed by love, and there's some awkward coincidence plotting, like an abortionist who turns out to be Makoto's sister's old boyfriend. But Oshima's portrait of a lost generation has some of the power of the American films that inspired it, Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955) and Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1950), as well as the French New Wave films about the anomie of the young by Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard. It was only Oshima's second feature, but it signaled the start of a major career.

0 notes

Photo

Joe Shishido and Yuji Kodaka in Cruel Gun Story (Takumi Furukawa, 1964)

Cast: Joe Shishido, Chieko Matsubara, Tamio Kawaji, Yuji Kodaka, Minako Katsuki, Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi, Hiroshi Kondo, Shobun Inoue, Saburo Hiromatsu, Junichi Yamanobe. Screenplay: Hisatoshi Kai, Haruhiko Oyabu. Cinematography: Saburo Isayama. Art direction: Toshiyuki Matsui. Film editing: Masanori Tsujii. Music: Masayoshi Ikeda.

My first impulse on watching Takumi Furukawa's Cruel Gun Story, with its whiplash double-crossings and piled-on violent deaths that reminded me of Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994), was to call it "Tarantino-esque." But that's getting it backward. Tarantino has said that he's "enamored with" the films of Nikkatsu, the studio that made Cruel Gun Story a good 30 years before Pulp Fiction, so by rights we should be calling his films "Nikkatsu-esque." Furukawa's film stars Joe Shishido, who was as essential to Japanese gangster films as James Cagney or Edward G. Robinson were to Warner Bros. gangster films of the 1930s. His glowering, jowly mug, usually with a cigarette plugged in its middle, is the essence of the tough guy. And like most tough guys, Shishido's Togawa has a heart of gold, devoted to his sister, crippled when she was struck by a car. She's the reason why, fresh out of prison, he signs on to a caper that involves the heist of an armored car. It's so elaborate a scheme, involving road detours and sabotaging the police radio and using a winch to pull the car onto a larger truck, that anyone who has ever seen a movie knows that it's going to go wrong. But even when it does, Togawa is able to come up with a Plan B, and then a Plan C, and so on, as double-crossers emerge from all corners. There's a sultry femme named Keiko (inako Katsuki) to add a little sex to the plot, but not enough to deter Togawa from getting revenge on the big boss who got him into this mess. The whole thing ends with more corpses than the last act of Hamlet, but it's done with such stylish efficiency that if feels like a better film than it probably really is. Which, come to think of it, is also Tarantino-esque.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Early Summer / Bakushū (1951, Yasujirō Ozu)

麦秋 (小津安二郎)

5/23/21

#Early Summer#Yasujiro Ozu#Setsuko Hara#Chishu Ryu#Bakushu#Chikage Awashima#Kuniko Miyake#Ichiro Sugai#Haruko Sugimura#Chieko Higashiyama#Kuniko Igawa#Toyo Takahashi#Shuji Sano#Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi#50s#Japanese#Japanese Golden Age#gendaigeki#families#marriage#postwar#siblings#girlfriends#children#Tokyo

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Repast / Meshi (1951, Mikio Naruse)

めし (成瀬巳喜男)

2/23/22

#Repast#Meshi#Mikio Naruse#Setsuko Hara#Ken Uehara#Haruko Sugimura#Yukiko Shimazaki#Yoko Sugi#Akiko Kazami#Ranko Hanai#Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi#drama#50s#Japanese#Japanese Golden Age#gendaigeki#Osaka#marital problems#jealousy#cats#relatives#marriage#visitors

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cruel Story of Youth | Nagisa Ôshima | 1960

224 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Early Summer - Yasujirô Ozu - 1951

Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi, Setsuko Hara

188 notes

·

View notes