#Hobbes

Text

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year Hobbes figured out how to turn the water on by himself. So late one night he turned it on .. but it was the hot water…. Now he sits next to the faucet and stares!👀 He is a quick study!

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 6 (quarterfinals)

Findus (Pettson and Findus) vs Hobbes (Calvin and Hobbes)

#this feels like an American vs European childhood kinda poll oh well#best fictional cat#polls#cats#competitions#pettson och findus#pettson and findus#calvin and hobbes#hobbes

711 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanted to try that colour wheel meme! I think the Doctor gets to count as a bit of a wild card...

#colour wheel meme#les mis#grantaire#mash#trapper#asterix#obelix#tintin#calvin and hobbes#hobbes#torchwood#ianto#lupin iii#hogan's heroes#lebeau#4th doctor#doctor who#trapper and grantaire don't understand a word the other is saying but they're vibing#depressed alcoholic who desperately wants to avoid fighting and use dark humour to cope... which am i describing#this was a lot of fun... i might do another one at some point and generate it by whatever suggestions you guys give me#see how weird we can make the mix#my art

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What are The Hunger Games for?" An essay on the fans' puzzling response to Snow.

This is basically my take on the entire TBOSAS discourse. [Warning: this will be long.]

The assertion that showing why a villain makes villainous choices (and why often from the villain’s POV they get reframed as morally good or right choices, so as to allow him to justify himself or self-excuse his own behavior to carry them out) is somehow “problematic” because it runs the risk of legitimizing his evilness or even praising it as a valid and commendable response to the world is by itself insulting and implicitly insinuates the idea that good and evil are not choices every human being makes, but rather independent constants that have nothing to do with each individual’s autonomy – when in fact the whole point of the book is that good and evil much closely resemble multiple differential functions whose variables can be extremely varied in both nature and number. In the case of Snow alone we already have: childhood trauma about the war, physiological trauma about starvation and malnutrition, staunch supremacist and totalitarian upbringing from Crassus and Grandma’am, poverty and scarcity that culminated in some kind of block or impairment in his physical growth and development during his teenage years and that most likely forever altered his metabolic and neurological processes to a significant degree, philosophical and ideological indoctrination from Dr. Gaul, social and economical collapse of his family’s wealth and reputation combined with the need and pressure to keep up appearances, etc. Claiming that Snow’s ultimately sick moral compass cannot derive from any of this is like claiming that nothing we experience in our formative years bears any role in shaping and defining who we become and what kind of choices we end up making.

That of Choice is, in my opinion, one of the most important themes of the book, and we really get a sense of this in the way Snow’s kills progress through the story, and particularly in how every next kill he engages in is the result of less independent variables that find themselves out of Snow’s direct control:

Bobbin; killed in straightforward self-defense after Snow is forced by Gaul to enter the Arena.

Mayfair; killed not in a life-or-death situation, but as a consequence of her threat to have both Lucy Gray and him hanged (so, this time the threat of creating a life-or-death situation is sufficient to provoke the same response).

Sejanus; killed as a result of a variety of fairly complicated variables, with most of them being directly dependent on Snow’s sphere of influence, intentions and interests, and deriving from what he deems as more important or morally correct for himself or what he believes in.

Highbottom; killed in cold-blooded cruelty and premeditation, with the murder being exclusively motivated by a desire to carry out evil without remorse, as Snow has finally reached the same conclusion Dr. Gaul was so eager to instill in him by appealing to his emotional attachment to his past and to his ambitions (which in turn stemmed from the traumas he went through), which is that every human being is actually evil at its core, and that the world is made up of victors who can exert evil with impunity and losers who just become victims of it.

Obviously Collins is not stupid and knows perfectly well that there are predispositions (also, if not mostly, genetically inherited, because at birth we all get handed a deck of cards we don’t choose and just have to learn to handle and master, whether we like it or not) that may make someone more inclined to do good or commit evil (Snow is indeed described from the start with narcissistic traits and sociopathic tendencies, but these seeds of his character get nurtured and watered instead of sublimated and eradicated because of what happens to him and the choices he’s pressured to make or deliberately chooses to carry out as a response to his circumstances), but I absolutely disagree with the kind of interpretation according to which the prequel demonstrates that Snow was always “destined” to be a villain because he was rotten right from his mother’s womb, just because it seems to me that there’s this giant terror in indulging the question “oh my God, what if evil is always a choice?” as it could be seen as an attempt to legitimize or excuse Snow’s behavior as an adult, when in fact, as far as I’m concerned, if would do nothing but condemn him doubly.

Essentially, claiming that Snow is a villain because he has always been evil and could have not been anything different literally provides ground to justify his actions behind the idea that he really didn’t have any other choice, and that everything he did was just the result of his villainous nature. This is exactly the same kind of thinking Dr. Gaul is able to inculcate in him, and that he exploits to be able to sleep at night knowing what he chooses to do during the day. The book obviously states the exact opposite, and in order to do so it has to argue that yes, Snow is a human being with the same moral layers and the same innate capability to be good and virtuous that everybody else has, but he has constantly rejected every chance he had to embark on a different path than the one he ended up travelling. Showing that Snow, the Villain, was made and not born DOESN’T mean that the author is justifying the character or that she’s patronizingly saying to us “oh poor soul, you better weep for him because he was a misunderstood victim of the system, etc” as I’ve seen so many fans argue since the novel was released back in 2020. It actually means that the character gets condemned twice by the narrative because he’s ultimately the conscious product of himself and the way he chose to respond to the world – and yes, that also includes to personal injustices and blinding traumas he experienced as a kid and didn’t deserve, and to circumstances that, as opposed to make him sympathetic to fellow victims who went through similar or comparable experiences, shaped him into someone who denies (or more likely, convinces himself of the impossibility) that human beings can even be genuinely sympathetic to each other in the first place.

Moreover, since I’m already on the subject, I’d like to add a little consideration regarding the fact that, if all of this about Snow’s character escaped so many people, then I’m not positive that the full political and philosophical message of the novel has been adequately understood by the fanbase, or that Collins’ brilliant idea underneath it has been adequately appreciated in its genius. The movie more or less manages to give it justice, but not completely. Because the book basically tells you: okay, The Hunger Games are the product of a school project by two drunk students, but they have been set up by a sadist (Dr. Gaul) and kept alive for 75 years by her pupil who she shaped in her likeness (Snow). Both Gaul and Snow argue that The Hunger Games exist to preserve all humanity (the so-called overarching order of things), and the reasoning they provide behind this conviction of theirs is very mechanistic, almost mathematical, stemming from naked economics and scarcity at least as much as, if not more than, existential considerations on the flaws of human nature. Gaul says, and Snow repeats: human beings are instinctively wired to be evil. This is testified by the fact that human beings, much like every other living beings, are dominated by a survival instinct that is capable of turning them into predators in order to avoid or preempt the risk of becoming preys. The possibility to become prey is a realistic prospect that the human being assesses and that, according to Dr. Gaul, demonstrates the inherent distrustful nature of Man (you don’t trust others not to kill you, as soon as you know they have the chance to and have to weigh that chance with the preservation of their own life). So, the notable conditions at the so-called “natural state” (civilization disappears in the Arena because the tributes are purposefully stripped of it) support the Hobbesian “homo homini lupus” view of humankind. Immediate consequence: if the species is to survive in any way, a means to control this primitive impulse towards self-destruction has to be devised (by the way, it’s interesting to me that Katniss herself also concludes that the human species gravitates towards that very thing at the end of Mockingjay, right after both Coin and Snow are dead). This impulse requires, so to speak, to be “parametrized”. So yes, Gaul says, and Snow repeats, that the world is nothing but a battlefield where a constant fight between people who are driven by this self-destructive impulse is carried out, and that whichever artificial construction built upon that impulse can only serve the purpose of obfuscating or hiding it, and therefore making us forget “who we really are”. So, this would apparently be what The Hunger Games are for: to remind us of who we are at the natural state, and therefore of what we need to keep human nature under control. And the movie (more or less) communicates this successfully.

But there’s actually a subtler layer to this. Because in the book Dr. Gaul even argues that, if the world itself is an enlarged Arena, if mankind is instinctively wired to self-destruct, and if peace is impossible, then The Hunger Games are not only a useful solution: they are a noble solution. Because their purpose is not to punish the defeated of a settled war. It’s to contain the scope of a war that hasn’t yet ended, and will never end. Even the conflict between the Capitol and the districts isn’t actually over: it’s just routinely ritualized, televised and sold as entertainment to the masses. And it’s much more convenient for everyone that a war taking place in the real Arena (the world) is contained in its catastrophic effects by periodically absorbing them in a highly supervised representation of a warlike conflict confined to a small, parametrized ground, which is much easier to control and leads to the loss of fewer human lives overall and the waste of fewer resources (let’s always keep in mind that Panem is a post-apocalyptic state). The genius behind the idea of The Hunger Games lies in this: in the ability, from those who have the upper ground, to believably reframe them as a noble management strategy for a problem that is actually without solution, but whose total control is of utmost importance.

All of this obviously applies IF one moves from the idea that human beings are innately evil. But the saga shows countless times, both in the original trilogy and in this prequel, that this is not the case, and therefore that The Hunger Games cannot be justified by any means, and are nothing more than a barbarity. And yet, Collins’ ability to pull you into the thoughts and meanderings of a sadist whose conclusions mostly derive from her own prejudices (which she takes as axiomatic) in order to make you understand why and how The Hunger Games have come into existence and have been gradually accepted by the dominant society is astounding and nothing short of genius. And this is also why I think TBOSAS was a necessary addition to write, as it basically fills a gap left by the original trilogy. You read the trilogy and you are left thinking “okay but Capitol City is beyond unrealistic because only a society made up of psychopaths could tolerate such an inhumane instrument”. Then you read the prologue and you understand that Capitol City’s point of view (deeply sick, but now scarily comprehensible) is that The Hunger Games, in the face of a deeply flawed human nature dominated by survival instinct and self-destructive impulses, are merely a strategic device whose ultimate function is to preserve civilization (by “parametrizing” the scope and development of a never-ending war) and allow the ruling class to maintain enough resources to keep the government afloat (thereby proving successful in contrasting the hegemony of the “natural state”).

Now, if I also deeply believed in this worldview and had been convinced since birth of its validity, and I belonged to the winning faction of a post-apocalyptic society that’s been relentlessly torn apart by war, I don’t know if I would see the apparent callousness of The Hunger Games as such an absurd price to pay in order to maintain what, according to what has been taught to me, is the only order capable of assuring the survival of the entire human species. As ugly and uncomfortable as it is, it’s still a political and philosophical dilemma that whoever is in charge of government and is responsible for keeping the whole country of Panem alive and functioning is obligated to face, whether willingly or not. So here we come to the typical leitmotiv of how power inevitably corrupts, but dealt with much more interestingly and thoroughly than how it’s conventionally explored in these kinds of stories.

All of this to say that, if we move from the assumption that to “humanize” Snow is to legitimize his evilness, and that he has engaged in all these monstruous acts purely because he was a monster through and through from the start, then we are playing right into Dr. Gaul’s hands and supporting her own thesis, as we are reducing the human experience to some kind of conflict between victors and losers whose nature is already predisposed and independent from the choices they make, and not only that: we are implicitly supporting the existence of punitive instruments like The Hunger Games. Because, if I take for valid that someone can be born evil and never escape this ontological condition, no matter what he does or doesn’t do, what prevents me from inferring that this may be the case for other people as well (or for everyone, even) and that something about human nature has to be fundamentally wrong? What prevents me from concluding that punitive or corrective methods to keep at least these unredeemable, inherently corrupt individuals under control should be established, and that to do so is a moral good? What prevents me from justifying the validity of barbaric, inhumane strategies detrimental to the fundamental rights of people in order to confront what I perceive to be as morally sound and perfectly justified needs because they are grounded on beliefs I think are true, or I’ve been sold as such?

A lot of still existing ideologies originate from specific beliefs about the intrinsic nature of certain groups of people in order to reach conclusions that appear to be legitimate for whoever embraces them but that in reality are actually horrendous and disgusting, which historically can lead (and in some cases have already led) to the establishment of sociopolitical systems characterized by such a disconcerting inhumanity as to be horrifying. And yet those were and are real people, with a personal moral conscience, that were and are able to do this (and still sleep at night) because so confidently self-assured to be right thinking “yes, those people are inherently subhuman/inferior/defective/violent/uncivilized and that’s because it’s their own nature, so I’m fully justified in the measures I take against them, no matter how dehumanizing they might be”.

Snow wasn’t a monster from the start. He chose to become a monster because he chose to believe Dr. Gaul when she said to him “any and all atrocities you might commit are not actually your own fault, because evil is inherent in all of us and coincides with our natural state, which means we can exploit it to impose what we deem as the most beneficial kind of control and order so as to save humanity from itself”.

And it’s in the climactic scene with Lucy Gray that every thematic knot is finally unraveled and Snow concludes (rather, chooses to conclude) that Dr. Gaul is right. Indeed, as soon as Lucy Gray realizes she’s now the only obstacle in the way separating Snow from gaining back the wealth and prestige of his family’s old name, she chooses to prioritize her own safety to the idea of trusting him or even giving him the benefit of the doubt, and quickly puts herself out of his reach to observe his next course of action from a comfortable distance, minimizing the risk of becoming prey. She fears he intends to kill her, so she grabs a knife and gains the upper ground, placing herself out of his sight. But from Snow’s internal monologue we know that at first his actual intentions are really just to speak with her, and doesn’t seem willing to hurt her at all. It’s the fact that he is still holding the rifle while making these internal considerations that ultimately prompts Lucy Gray to feel threatened, and therefore distrustful of him. So she hides and places a snake under the orange scarf, knowing he would be drown to it. She picks a non-venomous kind, because her intention is NOT to kill him, but to prevent him from killing her, which is what she thinks he is planning to do. She wants to neutralize him, or induce him to give up. And it’s, ironically, that very gesture that finally plants in Snow the idea of killing her, because he believes that she has tried to kill him and therefore that she wants him dead. The entire scene is genial because it’s a small-scale reproduction of a typical Hunger Games edition, where the theme I was talking about before comes to the fore-front: it’s the mere suspect, or the fear of turning into prey that urges someone to become predator. You don’t need to actually be a prey, you just have to believe you might become one. She fears he wants to kill her when he just wants to talk to her, so she sets up a trap for him: he misunderstands the trap as attempted murder, and reframes as self-defense his subsequent decision to try to kill her before she kills him. It’s a downward spiral of madness that Snow falls victim to that finally legitimizes, in his eyes, what Dr. Gaul has been telling him, because he sees that reflected both in his own behavior and in what he thinks is Lucy Gray’s behavior as well here: the survival instinct makes human beings evil at the natural state, so it has to be the role of civilization to keep this tendency towards self-destruction in check by constantly reminding people of what they actually are, bare of all their superficial artifices. Therefore, The Hunger Games are an instrument of civility.

From Snow’s point of view, he just wanted to talk to Lucy Gray in a civilized manner, but she hid in the forest to set a trap for him and tried to kill him with a snake out of the fear that he was going to abandon her and travel back to District 12. From Lucy Gray’s point of view, she sought refuge away from him to save her own skin and tried to neutralize a lethal attack with the hopes that a non-venomous snake bite could prove successful in disincentivizing his intention to shoot at her. Both misunderstood the ally-opponent by listening to their own instincts thus determining in the ally-opponent the kind of response that could justify their own convictions. Lucy Gray’s destiny is left uncertain, but Snow reenters the district borders having gone through some kind of existential epiphany, and the fundamental detail that the snake was non-venomous doesn’t even cross his mind in its implications and doesn’t seem to put at all into question what he has just concluded, because the actual, true realization he experiences in the forest is first and foremost about himself, and the way his own paranoia has completely validated what Dr. Gaul previously told him about human beings, and even about how Lucy Gray (in his own twisted recollection of events) has finally proved to him that they were not any different after all.

So, once he has chosen to believe that Lucy Gray was out to kill him, the circumstantial fact that the snake was non-venomous is quickly dismissed by Snow as non-relevant. But the snake being non-venomous is, incidentally, the defining element that finally allows the reader to properly differentiate Lucy Gray from Coriolanus when it comes to the dichotomy the entire novel rests on and that Collins herself has spent the entire story joyfully playing with (serpent/songbird). Because, confined again to the natural state, despite realistically fearing that he was going to kill her, and despite gaining even the upper ground and a significant chance to effectively anticipate him in the act, she ultimately chooses not to kill him. She merely chooses to try to neutralize him to secure a way out of the situation, or to force him to desist from any bad intention he may have in mind. This is not because Lucy Gray is incorruptibly good and Snow is incurably evil (the author strives for this to be particularly clear by reminding us that Lucy Gray still chose to kill inside the Arena even when she might have decided not to, sometimes with slyness and premeditation, prioritizing in that occasion her self-preservation to her moral integrity), but because in this occasion she chooses not to, in order to demonstrate to him the validity of what she had told him before: which is that human beings are not inherently evil, even when stripped of civilization, but that good and evil are always the products of conscious choices. Snow obviously needs to believe the opposite, because he needs to exonerate himself from the consequences of his own deeds and decisions. And Dr. Gaul gives him exactly that. And it’s within this framework that The Hunger Games become a justifiable instrument for the powerful, and for the society that it’s trained to accept and normalize them.

However, Collins’ own thesis is incredibly staunch on this: from Lucy Gray in this very chapter, passing through Reaper refusing Clemensia’s food and slowly dying of starvation to send a message to the Capitol, Lamina mercy-killing Marcus mirroring Cato’s death at the hands of Katniss in the original trilogy, Thresh sparing Katniss’ life as a tribute to Rue, all the rebel victors sacrificing themselves for Katniss and Peeta during the Third Quarter Quell, and arriving to all the oppressed civilians who willingly give up their own life to join forces and sabotage the Capitol’s industries, we are given plenty of demonstrations on how the natural state doesn’t eradicate human’s capability for choice, and how aprioristic thinking on the inherent evilness of our species (or of some subgroups of it) is not only wrong, but also extremely dangerous and easily conducive to the legitimation of barbarity and atrocity.

So no, I don’t agree with the idea that Snow was inevitably destined to be a horrible person because he had actually always been, and I absolutely don’t think Collins’ intention was to tell us this. He starts off the novel showcasing specific predispositions that cause him to oscillate between good and evil several times, and a lot of potential to eventually channel in either direction, but he ultimately makes the choices that he consciously decides to make (sometimes genuinely believing them to be the right or best choices, other times gaslighting himself and us into thinking he thinks that) up until Dr. Gaul offers him on a silver plate the ultimate opportunity to abdicate any and all responsibility on what he has done and what he’s going to do, which by the way stems from the same kind of reasoning behind this interpretation a lot of fans so desperately want to give of Snow (“man is evil by nature, so I’m just acting according to my own nature, and I’m doing it with the goal of safeguarding humanity and for morally positive ends”).

TL; DR: In a nutshell, what I mean is that the entire message of the saga, but especially of this prequel, is that The Hunger Games are an inhumane barbarity because they suppress and deny fundamental human rights behind a false promise to keep humanity safe from a self-derived tendency to devour itself that mankind supposedly strives towards because of its inherent evilness at the natural state. Collins demonstrates that such a promise is false because it’s fallacious, and therefore that The Hunger Games are nothing more than a gratuitous instrument of torture and death, discrediting the Hobbesian hypothesis that human beings descend into evil outside of the borders of civilization. And if that applies to all human beings, then it has to apply to Snow too (or Gaul, or Coin, for what is worth).

#thg#tbosas#the hunger games#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#suzanne collins#thg meta#katniss everdeen#coriolanus snow#lucy gray baird#dr. gaul#analysis#mine#hobbes

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When I was very little, my dad showed me all the Calvin and Hobbes comics. I grew up reading and loving this comic, and adoring the characters. It was fun to give drawing them a go!

605 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those pesky little creatures!

[Small? Loud? Annoying? They remind me of little gremlins in all sense. I decided to draw some Hobbes. Hobbes and their shenanigans since they have many. I love when they dress up as humans in their funny little outfits!]

#art#artists on tumblr#digital arwork#fyp#fable#fable games#fanart#fable 3#fable 2#fable anniversary#hobbes#unintelligible gremlin noises

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fight by Chris Thornley

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

He still vents in the woods.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flufftober Day 10

For the Day 10 prompt of "Love of Your Life" I wrote my first Calvin & Hobbes story.

Now You're Talking has Calvin in college, dreaming of writing a sci-fi novel about the adventures of Spaceman Spiff.

@flufftober

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 7 (semi-finals)

Hobbes (Calvin and Hobbes) vs Jiji (Kiki's Delivery Service)

#best fictional cat#polls#cats#competitions#hobbes#calvin and hobbes#jiji#kiki's delivery service#ghibli movie#still shadowbanned you know the drill

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Round, Matchup 1

Propaganda under the cut~

Propaganda for Hobbes: "He’s always down for an adventure", "Hobbes :)"

Propaganda for Pookie: None :c

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

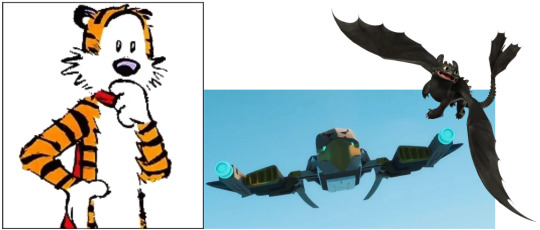

Hobbes v (the) Falcon v Toothless

Hobbes

Animal: Tiger

Person: Calvin

Media: Calvin and Hobbes comics

Falcon

Animal: Robotic Falcon

Person: Zane

Media: Lego Ninjango: Masters

Toothless

Animal: Dragon

Person: Hiccup Haddock

Media: How to Train Your Dragon

#non disney#nondisneyanimalbesties#yen sids poll#calvin and hobbes#httyd#lego ninjago#hobbes#toothless#falcon#tiger#dragon#how to train your dragon#hiccup haddock#calvin

67 notes

·

View notes