#I just have an increasingly complex relationship with any and all forms of internet culture

Text

Weekend Top Ten #482

Top Ten Sega Games

So I read somewhere on the internet that in June it’s the thirtieth birthday of Sonic the Hedgehog (making him only a couple of months younger than my brother, which is weird). This is due to his debut game, the appropriately-titled Sonic the Hedgehog, being first released on June 23rd. As such – and because I do love a good Tenuous Link – I’ve decided to dedicate this week’s list to Sega (also there was that Sonic livestream and announcement of new games, so I remain shockingly relevant).

I’ve got a funny relationship with Sega, largely because I’ve got a funny relationship with last century’s consoles in general. As I’ve said before, I never had a console growing up, and never really felt the need for one; I came from a computing background, playing on other people’s Spectrums and Commodores before getting my own Amiga and, later, a PC. And I stuck with it, and that was fine. But it does mean that, generally speaking, I have next to zero nostalgia for any game that came out on a Nintendo or Sega console (or Sony, for that matter). I could chew your ear off about Dizzy, or point-and-click adventure games, or Team 17, or Sensible Software, or RTS games, or FPS games, or whatever; but all these weird-looking Japanese platform games, or strange, unfamiliar RPGs? No idea. In fact, I remember learning what “Metroidvania” meant about five years ago, and literally saying out loud, “oh, so it’s like Flashback, then,” because I’d never played a (2D) Metroid or Castlevania game. Turns out they meant games that were, using the old Amiga Action terminology, “Arcade Adventures”. Now it makes sense.

Despite all this, I did actually play a fair few Sega games, as my cousins had a Mega Drive. So I’d get to have a bash at a fair few of them after school or whatever. This meant that, for a while, I was actually more of a Sega fan than a Nintendo one, a situation that’s broadly flipped since Sega stopped making hardware and Nintendo continued its gaming dominance. What all of this means, when strung together, is that I have a good deal of affection for some of the classics of Sega’s 16-bit heyday, but I don’t have the breadth or depth of knowledge you’d see from someone who, well, actually owned a console before the original Xbox. Yeah, sure, there are lots of games I liked back then; and probably quite a few that I still have warm nostalgic feelings for, even if they’re maybe not actually very good (Altered Beast, for instance, which I’m reliably informed was – to coin a very early-nineties phrase – “pants”, despite my being fond of it at the time). Therefore this list is probably going to be quite eccentric when compared to other “Best of Sega” lists. Especially because in the last couple of decades Sega has become a publisher for a number of development studios all around the world, giving support and distribution to the makers of diverse (and historically non-console) franchises as Total War and Football Manager. These might not be the fast-moving blue sky games one associates with Sega, but as far as I’m concerned they’re a vital part of the company’s history as it moved away from its hardware failures (and the increasingly lacklustre Sonic franchise) and into new waters. And just as important, of course, are their arcade releases, back in the days when people actually went to arcades (you know, I have multi-format games magazines at my parents’ house that are so old they actually review arcade games. Yes, I know!).

So, happy birthday, Sonic, you big blue bugger, you. Sorry your company pooed itself on the home console front. Sorry a lot of your games over the past twenty years have been a bit disappointing. But in a funny way you helped define the nineties, something that I personally don’t feel Mario quite did. And your film is better than his, too.

Crazy Taxi (Arcade, 1999): a simple concept – drive customers to their destination in the time limit – combined with a beautiful, sunny, blue skied rendition of San Francisco, giving you a gorgeous cityscape (back when driving round an open city was a new thrill), filled with hills to bounce over and traffic to dodge. A real looker twenty years ago, but its stylised, simple graphics haven’t really dated, feeling fittingly retro rather than old-fashioned or clunky. One of those games that’s fiendishly difficult to master, but its central hook is so compelling you keep coming back for more.

Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (Mega Drive, 1992): games have rarely felt faster, and even if the original Sonic’s opening stages are more iconic, overall I prefer the sequel. Sonic himself was one of those very-nineties characters who focused on a gentle, child-friendly form of “attitude”, and it bursts off the screen, his frown and impatient foot-tapping really selling it. the gameplay is sublime, the graphics still really pop, and the more complex stages contrast nicely with the pastoral opening. Plus it gave us Tails, the game industry’s own Jar Jar Binks, who I’ll always love because my cousin made me play as him all the time.

Medieval II: Total War (PC, 2006): I’ll be honest with you, this game is really the number one, I just feel weird listing “Best Sega Games” and then putting a fifteen-year-old PC strategy game at the top of the pile. But what can I say? I like turn-based PC strategy games, especially ones that let you go deep on genealogy and inter-familial relationships in medieval Europe. everyone knows the real-time 3D battles are cool – they made a whole TV show about them – but for me it’s the slow conquering of Europe that’s the highlight. Marrying off princesses, assassinating rivals, even going on ethically-dubious religious crusades… I just love it. I’ve not played many of the subsequent games in the franchise, but to be honest I like this setting so much I really just want them to make a third Medieval game.

Sega Rally Championship (Arcade, 1994): what, four games in and we’re back to racing? Well, Sega make good racing games I guess. And Sega Rally is just a really good racing game. Another one of those that was a graphical marvel on its release, it has a loose and freewheeling sense of fun and accessibility. Plus it was one of those games that revelled in its open blue skies, from an era when racing games in the arcades loved to dazzle you with spectacle – like when a helicopter swoops low over the tracks. I had a demo of this on PC, too, and I used to race that one course over and over again.

After Burner (Arcade, 1987): there are a lot of arcade games in this list, but when they’re as cool as After Burner, what can you do? This was a technological masterpiece back in the day: a huge cockpit that enveloped you as you sat in the pilot’s seat, joystick in hand. The whole rig moved as you flew the plane, and the graphics (gorgeous for their time) wowed you with their speed and the way the horizon shifted. I was, of course, utterly crap at it, and I seem to remember it was more expensive than most games, so my dad hated me going on it. But it was the kind of thrilling experience that seems harder to replicate nowadays.

Virtua Cop (Arcade, 1994): I used to love lightgun games in the nineties. This despite being utterly, ridiculously crap at them. I can’t aim; ask anyone. But they felt really cool and futuristic, and also you could wave a big gun around like you were RoboCop or something. Virtua Cop added to the fun with its cool 3D graphics. Whilst I’d argue Time Crisis was better, with a little paddle that let you take cover, Cop again leveraged those bright Sega colours to give us a beautiful primary-coloured depiction of excessive ultra-violence and mass death.

Two Point Hospital (PC, 2018): back once again to the point-and-clickers, with another PC game only nominally Sega. But I can’t ignore it. Taking what was best about Theme Hospital and updating it for the 21st Century, TPH is a darkly funny but enjoyably deep management sim, with cute chunky graphics and an easy-to-use interface (Daughter #1 is very fond of it). The console adaptations are good, too. I’d love to see where Two Point go next. Maybe to a theme park…?

Jet Set Radio Future (Xbox, 2002): I never had a Dreamcast. But I remember seeing the original Jet Set Radio – maybe on TV, maybe running on a demo pod in Toys ‘R’ Us or something – and being blown away. It was the first time I’d ever seen cel shading, and it was a revelation; just a beautiful technique that I didn’t think was possible, that made the game look like a living cartoon. Finally being able to play the sequel on my new Xbox was terrific, because the gameplay was excellent too: a fast-paced game of chaining together jumps and glides, in a city that was popping with colour and bursting with energy. Felt like playing a game made entirely of Skittles and Red Bull.

The Typing of the Dead (PC, 2000): The House of the Dead games were descendants of Virtua Cop’s lightgun blasting, but with zombies. Yeah, cool; I liked playing them at the arcades down at Teesside Park, in the Hollywood Bowl or the Showcase cinema. But playing this PC adaptation of the quirky typing-based spin-off was something else. A game where you defeat zombies by correctly typing “cow” or “bottle” or whatever as quickly as possible? A game that was simultaneously an educational typing instructor and also a zombie murder simulator? The fact that the characters are wearing Ghostbusters-style backpacks made of Dreamcast consoles and keyboards is just a seriously crazy detail, and the way the typing was integrated into the gameplay – harder enemies had longer words, for instance – was very well done. A bonkers mini-masterpiece.

Mario and Sonic at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 (Switch, 2019): the very fact that erstwhile cultural enemies Mario and Sonic would ever share a game at all is the stuff of addled mid-nineties fever dreams; like Downey’s Tony Stark sharing the screen with Bale’s Batman (or Affleck’s Batman, who the hell cares at this point). The main thing is, it’s still crazy to think about it, even if it’s just entirely ordinary for my kids, sitting their unaware of the Great Console Wars of the 1990s. Anyway, divorced of all that pan-universal gladhanding, the games are good fun, adapting the various Olympic sports with charm, making them easy-to-understand party games, often with motion control for the benefit of the youngs and the olds. I don’t remember playing earlier games extensively, but the soft-RPG trappings of the latest iteration are enjoyable, especially the retro-themed events and graphics. Earns a spot in my Top Ten for its historic nature, but it’s also thoroughly enjoyable in its own right.

Hey, wouldn’t it be funny if all those crazy internet rumours were actually true, and Microsoft did announce it was buying Sega this E3? This really would feel like a very timely and in some ways prescient list.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Robot Boyfriend: Questions of Autonomy and Manufactured Romance in a One Direction Robot Fanfic

If recent history is any indication, the general human public has become increasingly horny for basically anything sentient. From candy corporations tweeting lustfully about anthropomorphic foxes to erotic novels about flying reptiles, the boundaries of acceptable romantic sentiment are expanding at a rapid pace. A conservative may easily interpret this as the nadir of our decadent society, heralding the swift demise of our civilization. But the real story is much more complicated.

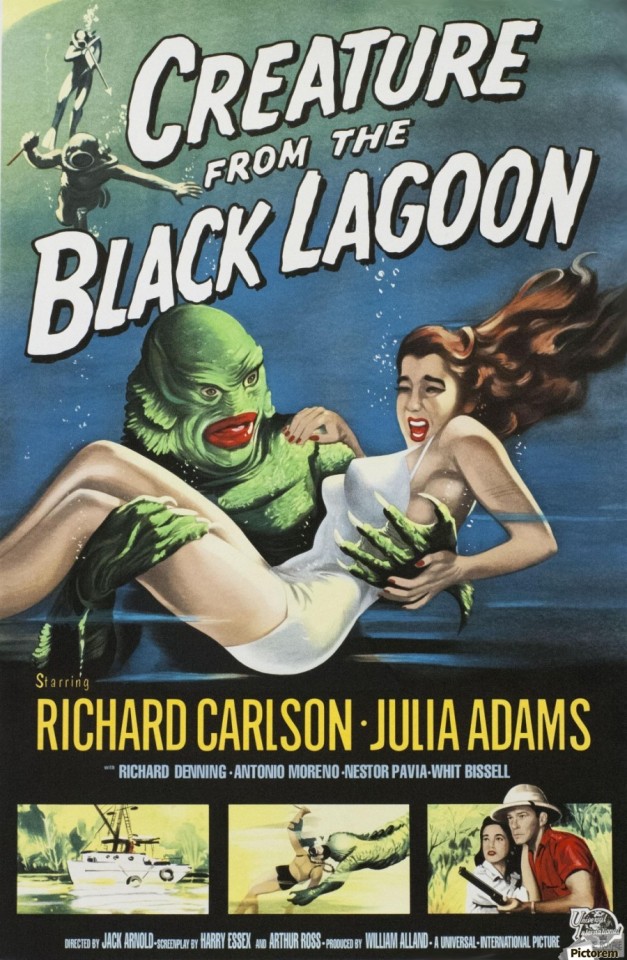

Monster novels and cinema have always been metaphors for the latent anxieties of a society. Initially manifesting in racist fears of desegregation and miscegenation in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the theme of white supremacist heroism triumphing over the control of the female body by a monstrous “other” is apparent in such later movies as The Neanderthal Man and Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Guillermo del Toro’s 2017 Best Picture winner The Shape of Water is deeply concerned with the dehumanization and unseen racism in monster movies, choosing to portray the monster and white woman in a genuine romance, while the handsome man that perceives them is the villain.

According to del Toro, The Shape of Water was an attempt to demonstrate that “the racism, classism, sexual mores, everything that was alive in ‘62, is all alive now. It never went away.” Del Toro characterizes the monster as a perceived negative aspect of society or personality that is initially distressing but can become liberating when embraced, explaining, “There are truths about oneself that are really bad and hard to admit. But when you finally have the courage and say them, you liberate yourself. All monsters are a personification of that.”

But what about...

Monsters have embodied a substantial collection of anxieties over the years: the rupture of the religious world by the scientific in Frankenstein, communism and McCarthyism in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the erasure of the past by modernity in King Kong. Robots, in comparison, typically represent a generalized technophobia, a fear of technology replacing the human, best represented by I, Robot (2004). They can also invoke questions of the nature of autonomy in an industrialized, capitalist society (Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times), fears of the transgression of the mind/body duality (2018’s Replicas), and imminent warnings of scientific and military hubris (Black Mirror’s Metalhead). So if romance with monsters can be a liberating embrace of the taboo, what function does romance with robots serve?

To answer this question, we could turn to the wide range of novels and films providing nuanced treatments of the complex ideas involved in human-robot relationships. Her (2013), Ex Machina (2014), Autonomous (2017), and He, She, and It (1991) are all beautiful, subtle considerations of robophilia, celebrated in science fiction and general circles. Unfortunately, my library card was revoked after failing to pay my 10-month overdue fee on Taken by the Pterodactyl, so that’s a dead end. I also don’t really want to pay to watch any movies, and the last time I went on 123movies.com I got a virus that pulverized my feeble laptop. Fortunately, the greatest, most boundary-pushing work on human-robot relationships is completely free of charge and within reach to anyone with an Internet connection. No expense is necessary to access this avant-garde treasure trove of communal literature, where robophilic desire meets ingenious analysis of our technology-ridden society.

I am speaking, of course, of the user pokemonouis’s love bot [h.s.] on the popular fanfiction site Wattpad. Before you click away in terror, consider that fanfiction can be a vital representation of culture, especially that of young people negotiating their place in a complex world. As the author Constance Penley says of Star Trek slash fic, fanfiction can be “an experiment in imagining new forms of sexual and racial equality, democracy, and a fully human relation to the world of science and technology.” With this framework in mind, let us dive into a sultry world of robot love.

In the vein of a typical Black Mirror episode, love bot [h.s.] is set in the present, near-identical to today except for one incongruous twist. Our protagonist, Ava, has been sent a mysteriously large package by her cheeky friend Niall Horan, containing an eager-to-please model from Love Bot, Inc., Harry. Though Ava is initially incensed at her friend Niall and is uneasy about Harry’s bizarre synthetic mind and body, she quickly warms up to his loving personality and sexual proficiency. Along the way, Ava must deal with her complicated newfound responsibility and the complexity of her own emotions.

Tragically, like Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor or Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” love bot [h.s.] remains unfinished. It was abandoned in 2016, and like One Direction, it doesn’t appear to be releasing any new material any time soon. Nonetheless, love bot [h.s.] is astounding in its complete lack of pretension or self-consciousness, existing as a complete, undiluted fantasy about getting a sex robot based on your favorite band member. However, the cherry on top is the dialogue created between the author and her readers, manifesting as a ludic communal debate about the philosophy involved or implied in the context of the world she has created. What I’m trying to say is that One Direction robot fanfiction is basically the 21st century version of the Athenian plaza or the Parisian salon, where the author’s story, as well as the community comments surrounding it, remain a portal of vital insight into such disparate themes as the commodification of sex and romance, the question of robot’s social standing given their initial utilitarian purpose, and the morality of human/robot pairings.

To enumerate, the foremost concern of love bot [h.s.] is the commodification of romantic love and its implications for how we relate to other human beings. From the moment Ava receives Harry, she is unwilling to engage with what she perceives as a mere corporate commodity, surrounded by packing peanuts, a charging port on its lower back. When Harry boots up, Ava is immediately accosted by the manufactured nature of his existence:

The comments echo Ava’s sentiment. One user states, “I’d be creeped out. Imagine if there was a camera or something.” Another jokes, “in the middle of doing what he does best, Harry whispers in my ear, “please like love bot incorporated’s page on Facebook!” This combination of the romantic with the heavily marketed is not new to the 1D fandom, as the band’s image, promotional events, song lyrics, and music videos all serve to encourage an attachment between fan and musician. However, to assume that the average fan mindlessly consumes the marketed content is to ignore the self-awareness within the 1D fandom. For instance, 1D fan culture often repudiates the perceived manufactured nature of their idols; many fan works bemoan the band members’ “management,” or the behind-the-scenes music industry professionals who prevent the boys from living life to its full potential. Thus, the Harry Styles sex robot becomes a potent metaphor for the fans’ relation to their favorite musicians, a playful way of acknowledging that you’re being pandered to yet still enjoying the show. In keeping with the framework of monsters provided by Guillermo del Toro, to engage romantically with the robot is to embrace the messiness and weirdness of emerging sexuality despite society’s opinion of 1D fans as crazed, lustful, and corporate-brainwashed young women.

Love bot [h.s.] also presents an interesting exploration of robot aesthetics and how they are constructed to appeal to humans. Ava is initially rather put off by the combination of the synthetic and the natural found within Harry’s body:

Despite this, she eventually comes around to Harry’s physical appeal, particularly due to his “cuteness:” Ava’s affection grows after he adorably takes the expression “you’re a dime” literally, uses the phrase “take a sleep” instead of “take a nap,” and is caught using her computer to look up “how to impress a girl.” According to scholar Sabine Payr, robots in popular media tend to either be nearly indistinguishable from humans, in which case they occupy the space of the “uncanny valley,” are threatening, and must be destroyed (as in Blade Runner or Ex Machina), or are presented as non-threatening “sidekicks,” whose cuteness and helpfulness to humanity mark them as peaceful (Wall-E, Star Wars’ C-3P0 or R2D2). Harry is gradually brought out of the former category and into the latter through his cuteness as well as his utility to Ava, such as through cooking her a delicious breakfast. As one commenter succinctly puts it, “It kinda creeps me out that he’s a robot but he’s freaking adorable so whatever.” However, this transformation of Harry has the possible negative consequence of him not being seen as fully equal to humans, as his “adorableness” is contingent upon him occupying a lower social position than Ava. Nevertheless, though most readers seem somewhat put off by Harry’s robotness, many seem just as ready to engage with the “uncanny valley” robot as the “adorable” one. For example, in response to Ava calling Harry "too real, too creepy," one user responds, “Well Send him over to me and call me Goldie locks cause he’s just right.” This sentiment is repeated throughout the first chapter: for every “This is going to turn into some Chucky shit for sure” there appears a “Call me Shia Labeouf cause I’m about to get it on with a transformer.” The readers willing to engage with the “uncanny valley” Harry avoid the problem of inequality inherent to the subjugation of the robot to a “sidekick” role. Thus, in this case, engaging romantically or sexually with the robot may be a potential expansion of the social category that robots may inhabit, a radical rebuke of the idea that robots must be subordinate to humans to be lovable.

Similarly interesting is love bot [h.s.]’s theme of autonomy: can one form a healthy relationship with a sentient being that is bought and customized to love you? Throughout the narrative, Harry refers to Ava as his “owner” or “master,” and Ava frequently treats him like a friend’s dog that she has been left to take care of. Harry gets separation anxiety when she leaves to attend school or work, is constantly compared to a puppy, and is described as a “burden:”

However, the readers were quick to push back on this characterization of Harry. Angry commenters lashed out at Ava, stating, “HES NOT A FOOKING BURDEN” and “HARRY DOESNT DESERVE YO RATTY ASS.” Readers of love bot [h.s.] reject the notion of a love bot as a less than human, asserting their right to be recognized not as a product or sex slave but as a full and realized autonomous being. However, as commenters repeatedly point out in another section of the fic, such a relationship is suspect. Ava is eager to downplay the uniqueness of her relationship with Harry, mostly ignoring his robotness in favor of labeling him as just another human:

Commenters are quick to point out the contradictions within this statement, replying, “except for him bc he is a literal robot who was made to be owned” and “says the girl who literally owns a robot im fed up bye.” Ava may treat her robot boyfriend as an equal, but, as the readers indicate, the nature of their relationship is inherently unequal. After all, the fic mentions that the love bots are, in legal terms, basically slaves:

Harry is completely dependent on Ava, and, tragically, only able to shop at Sears. With the realities of this society, the commenters argue, Ava’s “you are your own person and you belong to yourself” statement is functionally meaningless. Commenters also occasionally bring up other questionable power dynamics within the context of Ava and Harry’s relationship; one states, “Imagine if they got in a fight, she could just power him off;” another asks, “What if she died?” after a sentence highlighting Harry’s extreme dependence on Ava; another mentions, “that sentence is making me remember that he's a robot & can be programed at any time :((.” Harry’s boundaries of mind and body are much easier to manipulate than Ava’s, and this presents a quandary; can a robot partner ever be in full control of their internal psyche if his mind is specifically manufactured to carry out a single purpose, and that mind can be tampered with at will? The rich dialogue created between the author and readers gradually teases out several ethical considerations involved in human-robot relationships, questioning whether any relationship between a human and a robot constructed out of pure function can ever be helpful. In this context, the readers redefine the act of loving the robot as not a simple act of passion, but a commitment to upholding the autonomy of one’s partner.

The playful exchange between the author of love bot [h.s.] and her readers illuminates the moral gray area of human/robot relationships, offering key insights into the nature of commodified romance, social categorization of robots, and unequal partnerships. If/when artificial intelligence advances and potentially becomes sentient, the willingness to have debates about these topics will be essential to the creation of a just society for humans and robots alike. As Guillermo del Toro reminds us, the hierarchies and unquestioned assumptions of today will persist into the future, and a potent way to resist them is through the act of loving the taboo. It would be unwise to dismiss it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Focus on the Fan-mily: Community Archiving and the Archive of Our Own

A five-part series on AO3 as a community archive, considering how archival theory and fandom history meet to create a ground-breaking fan archive experience like no other, and the possibilities this has for the archival profession moving forwards.

Full essay (with citations) here

Part I | Part II | Part IV | Part V

Part III - Chasing the Ephemeral: An Overview of Fan Archival Activities

To understand AO3’s insistence on enabling the creator with full power over their works, it is important to understand the fan culture and context that AO3 developed out of, as well as the complex history of fan archival activities. Since the early days of modern fan culture, with Star Trek fans in the 1960s, fan spaces have been a place of sub-culture and secrecy, with transformative works and fan fiction —the dominant form of record on AO3— being particularly revolutionary. Fan academics such as Abigail Derecho often identify fan fiction as a form of societal criticism, predominantly created by women and people from minority groups. Using fan fiction, fans from marginalized groups create content for themselves that reimagines the hierarchical and societal norms reflected in the original media and wrests control of storytelling and creativity away from mainstream capitalist studios and publishers. This content often contains themes and subjects considered counterculture or radical by mainstream society — for example, until very recently (and arguably in some corners still), this included any queer interpretations, feminist discourse, or erotica. At the same time, fans use the spaces in and around this content —the writer-reader relationship, the aggregation of stories with similar subjects, the use of particular tropes and specialized lingo— to create a community and culture that reflects their own, often marginalized, experiences. Particularly with the connectivity of the Internet, Abigail De Kosnik observes that digital fan fiction archives become “safe spaces” where fans with similar experiences can “come together, sharing ideas and experiences without fear of silencing.”

This “fear of silencing” has long plagued fan spaces and has come both from within and without communities. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, fans largely shared their content through zines and amateur press associations, relying on conventions and meet ups to come together with other community members and distribute their work. With the advent of the Internet, fan communities —known as fandoms— began to attract a new and wider scope of members. Now younger fans, international fans, and even people who had never heard of fandom before, could connect with existing communities so long as they had access to an Internet connection. A fan scholar by the pseudonym of Versaphile observes that early digital sites were particularly ephemeral in nature — posts and discussions on forums had a lifespan of days or weeks, and it wouldn’t be until the mid-1990s that sites began retaining user content. Major archives dedicated to fan fiction began emerging in the mid 1990s, usually centred around stories from a single fandom. These early archives would perhaps be more recognizable to archival professionals — users posted their content or submitted them to the web archivist, who would format, file and preserve the materials they received in order to make them available to archive users. Creators could request that their content not be archived, or that their previously archived materials be deleted, but generally, archives retained their materials until they were dissolved or deleted.

While there were technical issues with these early archives, such as poor accessibility and search functionality, one of the greatest threats to these archives was the loss of their archivists. Once an archivist lost interest in the fandom, or was no longer able to manage the archive, the entire site could disappear as maintenance ceased, domains expired and were not renewed, and reorganization destroyed years of existing structure and links. This is a common concern with community archives, particularly those of the Do It Yourself variety — as Rebecka Sheffield observes, the loss of interest from archive members or the inability to maintain the existing collection has led to the disappearance of many archival projects. With the disappearance of each archive, years of fandom discussion, content, and community were lost forever, unless individual members made a special effort to preserve certain elements on their own ends. Fans began to learn an important lesson that would continue to shape fandom for years to come — their communities, the stories they created and shared, the unique fandom cultures and relationships that they had developed, even the shared memory of their own history, was only as stable and permanent as the whim and will of the site administrators.

As fans explored different methods of communication and content sharing into the early 2000s, the role of the administrator remained a question. Mailing lists centred around a particular theme, genre, or relationship provided a decentralized and highly tailored fandom experience at the cost of accessibility. Links to content were closed to non-members, who had to apply for membership with the list’s moderators just to access a single story, and moderators had the power to delete entire lists whenever they pleased, thereby deleting all the works preserved within. The popular journaling website LiveJournal dominated fandom communities through the early 2000s, granting creators seemingly exclusive control over their own content. Creators could make their journals public or private, and rename, hide or delete them altogether. Accessibility remained an issue: content was poorly and inconsistently tagged, the search function was nigh non-existent, and users had to develop through experience a knowledge of which journals might contain content they were interested in and what terms a creator might use to describe their work. Although some users began developing general guides for creators to describe and tag their work, compliance with these guides depended on the individual creator. With the rise of the creator’s autonomy over their own work came issues of organization and management, and the ever-present question about the preservation of content.

While fans wrestled with the question of intracommunity preservation, outside forces began emerging as threats to fandom communities and creators, as litigation, censorship, and commercialization began targeting fan spaces. In the late 2000s, LiveJournal saw several waves of migration to other sites as website staff began banning users en masse and taking down content which they judged to be immoral or illegal. These takedowns, supposedly aimed at sexual crimes, could affect any content that involved sex — from age-restricted adult fan fiction journals, to sexual assault survivors’ spaces, to queer fan fiction, which was seen as inherently sexual regardless of content. Similar censorship restrictions affected other popular fan hosting sites, such as Fanfiction.net, which was in many ways a precursor to AO3. As a centralized, multi-fandom site with a relatively organized structure, Fanfiction.net provided fan creators with the ability to format and post their own stories in one place, and enabled users to find and access those stories with comparative ease using a controlled vocabulary with its descriptive elements. However, throughout the mid-2000s to the early 2010s, the website began imposing restrictions on the kind of content that fans could publish. Adult fan fiction was banned, as was any content which could potentially result in litigation from a studio, publishing company, or author. Creators issued lengthy disclaimers with each post, making it clear that they did not own the original media or characters on which their fan work was based. It was vital that no one could argue in court that they had given any impression of owning the intellectual material, as there had been high profile cases of authors suing and harassing fan writers. Works containing quotations of more than a few lines, such as a stanza of a song or a paragraph from a book, ran the constant risk of sudden deletion by administrators. Users became increasingly disgruntled with the censorship and the constant fear of deletion by site staff.

The intrusion of mainstream capitalism also began to challenge the sub-culture of secret community that many fans had become used to. As “fandom” became increasingly prominent, corporations saw fan communities as a potential resource. For media companies, fan content produced through free fan labour increases the presence and reach of the original media. Popular fan sites were also profitable places for ads, and web servers and companies benefitted from the increased traffic. In the eyes of many fans, this was nothing short of exploitation. Coming from a strongly decentralized period in fan history, fan spaces were seen as personal and counterculture — fans made the content they wanted to consume for their communities, not for their own profit, and certainly not for the profit of large corporations. The increasing presence of commercial ads on fan sites such as Fanfiction.net was insulting, and the creation of the notorious FanLib.com in 2007 was even more so. If the presence of ads on sites like Fanfiction.net —where users feared that failing to write a clear enough disclaimer could be interpreted as an intent to profit by lawyers— was controversial, then FanLib, which was designed to profit off of fan fiction and which boasted paid promotions from media companies, was intolerable. The FanLib debacle was the last straw, and outraged fans, frustrated with censorship and corporate intrusion and the loss of communities and cultures over the years, began to organize.

It was against this backdrop that the OTW formed, and it was in light of these discussions around the preservation of fan culture and history, the questions of censorship and profit, and the rights of fans, that fans created AO3 in 2008, with the site going into open beta in 2009. Their rallying point was the idea of “owning the servers,” creating a centralized space controlled by fans where their communities and creators could exist in safety and stability, creating the content that they wanted without fear of deletion, censorship, or exploitation, which by its long-term preservation would help keep alive the fan cultures and communities that produced it. With personal experience in fandom and previous fan archival projects, AO3’s creators were familiar with what fans needed or looked for in an archival space. Accessibility was a must. To that end, AO3 maintains a highly sophisticated descriptive tagging system, with volunteer “tag wranglers” interpreting and linking unique creator tags with larger related tags, preserving the creator’s descriptive intent while facilitating access to their works. Autonomy was balanced with archival preservation — creators can submit and describe their works however they feel is best, and retain rights of deletion and anonymity, while leaving the archival work of preservation, management and accessibility to site volunteers. Crucially, and sometimes controversially, AO3 permits fan content containing any subject without fear of censorship or deletion. While users may submit complaints about individual works, and creators must still abide by the laws of their jurisdiction, AO3 enforces the rights of creators to create without fear of censorship or arbitrary deletion. AO3 also operates entirely as a noncommercial and nonprofit organization with no ads or user fees, relying on a fan volunteer staff and annual fundraising drives.

Despite all the answers AO3 proposes to issues such as fan preservation, censorship, accessibility, and rights, many questions remain from both an archival and a fannish perspective about AO3’s role and functions as a community archive. Just who is included in this community “of Our Own?” What kind of cultural memory is being preserved, and how? What is included and what is left out? How does AO3’s commitment to freedom of the author relate to offensive content? If the subculture being documented in these records is, by nature, counterculture, why seek legitimacy from mainstream institutions? And in what ways does AO3 actually serve its users as a community archive, apart from making it easier to find a good read for a few hours?

Part III Sources

De Kosnik, Abigail. Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016.

Derecho, Abigail. “Archontic literature: a definition, a history, and several theories of fan fiction.” In Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet, edited by Hellekson K and Busse K. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. Quoted in A. Lothian, “Archival Anarchies: Online Fandom, Subcultural Conservation, and the Transformative Work of Digital Ephemera,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16, no. 6 (2013): 545. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912459132

Johnson, Shannon Fay. "Fan Fiction Metadata Creation and Utilization within Fan Fiction Archives: Three Primary Models." Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 17 (2014). Accessed December 10, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0578.

Lothian, Alexis. “Archival Anarchies: Online Fandom, Subcultural Conservation, and the Transformative Work of Digital Ephemera.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16, no. 6 (2013): 541–56. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912459132

Sheffield, Rebecka. “Community Archives.” In Currents of Archival Thinking, 2nd ed., edited by Heather MacNeil and Terry Eastwood, 351-376. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited, 2017.

“Strikethrough and Boldthrough.” Fanlore. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://fanlore.org/wiki/Strikethrough_and_Boldthrough

Versaphile. “Silence in the Library: Archives and the Preservation of Fannish History.” In "Fan Works and Fan Communities in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," edited by Nancy Reagin and Anne Rubenstein, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 6. (2011). Accessed December 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2011.0277.

1 note

·

View note

Text

CONNECTIVITY AND THE CULTURE AND SOCIETY

How does communication create, maintain, or modify culture and society? To answer this question we must first start off with defining what communication, culture, and society is.

Communication is the process of conveying information or meanings through words or symbols in order for one to connect between one entity or a group. Mass communication on the other hand is communication within a wider range of audience. Meanwhile, culture and society, though totally different with each other are two things which are coexistent. Culture won’t exist without society and so as society in the absence of culture. Culture, though interpreted in many different definitions is defined by most scholars as something that is shared among groups of people with shared history, values, knowledge and tradition. Society then would be the outer structure, a group of people living collectively on a wider social group with a systematic form of relationship.

With the occurrence of new technologies, our means of communication had gradually changed and the effects this new media to culture, society, and communication itself are creating debates whether it would make or destroy us.

MEDIA COMMUNICATION TRANSFORMS CULTURE AND SOCIETY

Some scholars say that communication itself is responsible for the emergence of culture. With the increasing rampant use of the internet and use of social media as the main medium of communication comes the wider and larger scale of information transmission and communication. Through the internet people nowadays can create connections with other people even from great distances which enable them to communicate and form groups with other people of the same beliefs and interests across the globe online. This is deviant from the kind of society before in which people of the same culture can only communicate through limited types of medium and are only concentrated within a specific area or a community. The world right now is connected through a vast online network and created a new cultural environment called a “Global Village”, a term coined by Marshall McLuhan explaining how the entire world shrunk into one village with the emergence of electronic media, linking everyone in all parts of the world into a complex network of communication. The communication we have with other people from across the world enables us to obtain and learn culture from different places and people in which we can subject to personal interpretations, thus, allowing us to change our own perception of the culture and society each of us were ascribed to and gives us the power to choose whether to keep conforming or to deviate from the norms.

CREATING SOCIAL NORMS

Social norms are integral in forming and reshaping the culture within a society. The more the people communicate about something increases the chances of it becoming culturally and socially normative. Communicating what we perceive to be relevant traits repeatedly increases the chances of it remaining as a normative characteristic. Some things are more likely to be talked about above other things, and as long as it is talked about would give rise to popular opinions and stereotypes within the society. For example, the emergence of social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter instantly became a need for 21st century people and most specially the teens because most information, news, and socialization are obtained from these platforms. Not having an account on any of this social media platform means that you’re being left out from the rest of the world, which made the idea of having an account as a norm. That’s why some people directly ask another person of their account name on Facebook or Instagram when they want to get to know them rather than asking whether they have an account in the first place. With the idea of having an account on these platforms a norm, popular stereotypes in fashion, beauty, and even ideology or of many other sorts are increasingly widespread through Pop Cultures. People with power such as the capitalists, the church, and even the government could use this platform to persuade, create and even impose norms to the society.

POWER AND DEVIANCE

The concept of Power existed through the process of communication. Different institutions that organize our society are largely constructed in our minds through the communication process. They have the power to manipulate how ordinary people think, feel, and behave. The media technology created a new medium for power strategies to take place. Most power figures are persuasive in communicating their preferences and would sometimes demand for conformity. Many influential authorities could modify or maintain cultures just by simply communicating their beliefs and expectations. Culture and society could be maintained when the people choose to conform, but sometimes, persistent imposition of a cultural norm could be coercive and sometimes backfire. People might feel restricted from their freedom and start to question a cultural norm in its validity and even inspire deviance from this norm and seek ways to express their decisional freedom instead. Though social media could be a platform for the powerful to be in control, it also gives the opportunity for the ordinary people to voice out their opinions regarding imposed norms. This gives them the potential to have power instead and change culture as the society knows it.

IS MEDIA CREATING OR DESTROYNG?

The fast development in technology had created the condition of communication at lot easier for us and through the past decade became an essential part of our daily lives by stimulating our own thoughts with providing various information which were made easily accessible. Though media communication had presented us with constructive roles in the society such us providing us a wide platform of gathering information and bringing everyone in all parts of the world closer, I believe that in most ways it has a greater potential to destroy our own culture and society. Media platforms give too much freedom to its users and sometimes people tend to abuse this newly obtained freedom. Conflicts can arise online due to the differing opinions between different people and sometimes social taboos such are even being defended or and depictions of sex and violence are increasing in different media contents. This could be bad to the young readers who might see these sensitive contents and be mistaken on interpreting what’s right or what’s wrong and inspire people to do crime or be disobedient to the law, something that keeps our society organized. It’s true that the world gets closer because of media, but with the use of it and its benefits comes our own privacy. The world gets smaller and our personal information are being leaked without us even knowing it. As long as our personal information is contained in the internet the problems of leakage would always be in question.

Whether media technologies would be constructive or destructive to society would now depend on how each of us use media as a form of communication. But for now, I think that its negative effects on our behavior and communication are outweighing its potential to give a positive effect on our society. Its ability to provide people with either their own subjective or objective opinions could potentially cause chaos.

1 note

·

View note

Text

October 2020

Dark Study Application:

Please tell us about yourself.

*

(1) How do you see your practice benefiting from our program’s general mission? Why does it resonate with you at this point in your life?* (546 Words)

Within the span of last three years, my own worldview has been swiftly transitioning from wanting meritocratic institutional amplifiers and then seeking mentorships from the individual gatekeepers of these competitive fields and now to surround myself with a certain kind of community that is both inclusive and intimate enough to creatively employ our collaborative resistance and existence. All of these continuous transitions are both riddled with the baggage of spiritual taxations and the appeal of inspiring alternatives.

Just as the admits to theories and practices housed within western institutions personally render to me as impractical and confining, I am also now being introduced to the idea of Dark Study here on the internet as a radical alternative whose ideology goes beyond simply responding to the ongoing COVID realties. As I feel excluded from the concerns, theories and practices of the land I belong to, I also feel removed from economic and cultural possibilities of inclusion in neoliberal western institutional settings I am invited into. In complete contrast to this, Dark Study here appears to promise a global assimilation in its community which specifically takes down the economic barriers on these gateways. Perhaps, I never encountered a community more welcoming. In the institutional choices available to me both globally and domestically as a dalit lower caste person in an increasingly hegemonic upper caste hindu rule in seemingly the biggest functioning democracy in the world, I have often either self-excluded or felt excluded. This very exercise of submitting my essays with an intention to get my self-selection for The Dark Study program validated helps me against the accumulated anxiety and helplessness so far.

With a clear hope to accumulate social capital through western access and validation, I once had romanticized the idea to fetch political power and cultural attention to the dalit lower caste sections of the society I come from. Just as I started to discover the neoliberal shortcoming and hypocrisies, I started to question my own spiritual strength in an art culture in the larger society that was anyway increasingly punishing and exclusionary to the experiences I wanted to articulate. With economic fragility and lack of access to a community with similar goals and experiences, I currently feel an affinity towards marxist unification of a worker and an artist in a person. All of us are artists anyway and all of us need to work. My such interpretation of a cuban filmmaker by Julio García Espinosa’s reflections on an imperfect cinema is currently asking me to seek a regular day job in this capitalist setting and express myself in the evenings. My current work is a product of intimate gaze through a self-compassionate lens on the psychological complexities produced within a familial setting that is informed by socio-political histories and surroundings. My art is primarily an expedition within the self and which is why a capitalist mind may render my art as non-work. Just as I continue to grapple with the material equations to facilitate my future as a dedicated artist in isolation, I also feel blessed to witness Dark Study as a promising community in the making to host and inspire creative alternatives. Within the fraternity shelters of Dark Study, I anticipate it would be less lonely and less jarring to study for alternative solutions.

*

(2) We are hoping to build a rich virtual community. What do you seek from an online community, and how have you been living online? How do you see yourself helping to build community within this learning platform?* (419 Words)

I see myself as a part of the section that creates and consumes art primarily in digital forms. The Internet as a gallery promised me a democratic space with universal access when I had just started expressing online. My practices evolved and changed as the internet evolved and changed over the last five years. But these practices and evolution were largely at the mercy of social media platforms. Though the attention span these social media platforms offer to our expressions are limited, the durability in the form of a permanently accessible online record was nonetheless motivating in the culture of solitary art making. The Internet’s potential as a language and technology in itself recently started to interest me to further look at it as a primary medium for creating expressions. Web Development and Processing Coding Language are my newly picked up self-education assignments. I intend to patiently acquire skills and practice Internet based interactive web pages as a medium for my expressions.

Knowledge creation as a rigorous individual process in an essentially collaborative pursuit is my idea of communal cultures that is also not exclusionary in the guise of meritocracy. I have never had an experience of being a part of an artistic or political community yet. Dealing with anxieties and loneliness often swindled my priorities, influenced my decision making process and limited the scope of my study. A community, bonded through similar set of values and experiences yet fostering diversity in approaches and positions, promises a pool of cognitive and knowledge resources to share. At Dark Study, I anticipate a formation of such community where I could get inspired and informed about media, technology and coding avenues and also share my own political growth as a lower caste dalit person.

I see The Dark Study community as a possible alternative for kinship as well. Dark Study with its commitment to diversity and inclusivity, can also evolve into an active kinship that amplifies the process of healing and the courage for resistance. To be a part of such communities and to collectively find ways for replicating and reproducing many of these experiments with their own autonomy to reshape and repeat, wasn’t as inviting as it is with the promise in the potential of Dark Study. Yet, even with these preformed ideas, I am still indefinite and unclear with curiosities about how I see myself interacting within this community. I currently see these interactions and relationships shaping themselves with the future experiences they decide to remember and to reflect upon.

*

(3) Please tell us a different version of “your story”, your alternative biography, as it relates to your creative development. This can include your access to - or exclusion from - opportunities, your relationship to institutions, and your class position. For example, what was your first experience with labor and compensation - hidden or unseen, paid or unpaid - of any form? Our aim, here, is to understand how these assembled life experiences shaped your attitude towards both education and art, and further, would inform your work in Dark Study. (Please take a look at "People" on darkstudy.net for an example of what an alternative biography might look like.)* (991 Words)

I identify myself as a visual artist who has been using digital media to reflect on relationships in his life through an intimate lens to recognize and heal through traumas induced by intergenerational, casteist and patriarchal residues. My ongoing studies involve understanding the psychological complexities that inform the replication of interpersonal relationship patterns in socio-political contexts, learning to use digital media with internet infrastructure to create-curate accessible technophilic content and finding ways to economically support-sustain practices.

I also happen to hold two engineering degrees from one of the most prestigious institutes in my country. The honeymoon days of this meritocratic dream couldn’t always distract me from the mental illnesses that had just started to show up in my small nuclear family. My mother’s paranoid schizophrenia, my father’s depression and my own bad performance in my college bagan their own triangular dance steps around that time. I wasn’t cognizantly equipped to get to the roots of this at the time, but I started to express myself through abstract and cryptic graphic designs. Both the shame and ignorance, about intergenerational trauma and internalized caste dynamics within the family which was also a part of larger society that stays in the denials of casteist and patriarchal influences, convoluted my process to seek articulation and healing.

Soon after my parents and I began receiving medical attention for the mental illnesses we all had slipped into after years in ignorantly replicating interpersonal traumas, we all also began to heal and repair our familial bonds. Around the same time, I had decided to continue my interest in documentary photography once I finish my engineering degree. Our family, which had just started to recover from long ignored mental illnesses, felt triggered once again because of my wish to change my career path. Both my parents are first generation college attendees. My father’s job as a school teacher broke the poverty cycle. As I was growing up in an Indian village in a lower caste community, my mother, who’s also a housewife, decided to bring me to a town in the hopes of providing me with better education opportunities. With the new spatial privilege and exposure from a town, I was able to further capitalize on the progress made by my parents and continue a shallow relentless pursuit of meritocratic validation. I had earned a place in the most elite engineering institute in the country and letting that rare privilege go ‘waste’ was very upsetting for my parents who were still struggling with the present and past of social imprisonment. Yet, while I was informing myself with the problematic histories of colonial gaze as a part of my self-education to learn documentary photography, I had started to discover possible analogies between racial divide in global context and caste divide in indian context.

Around the same time I was being exposed to the history of black american photographers and their relationship with their own community within the american context. My interests in black scholarship and black feminism had already started to provide me with vocabulary to articulate my own experiences with caste and class in indian context. Photographs by Gordon Parks and Deana Lawson and words of Fredrick Douglass and Sarah Lewis started to influence and motivate my documentary work very deeply. Their language of compassion and grace overwrote my previous ambitious make to do ‘big’ in photojournalism. Around the same time, I started to revisit the indian scholarship on caste and dalit lower caste literature. Dr B R Ambedkar, who is also a contemporary of Dr W E B Du Bois, though his writings, inordinately helped me repair and reclaim my self-esteem. After being introduced to the photographs by Carrie Mae Weems and words of Ta Nehisi Coates along with the self-awareness from a social lens once again radicalized me. I started to feel like I might have been using my interest in documentary photography as proxy mourning for the intergenerational mourning I had denied myself.

I had started to turn my camera towards my own family as I continued to read Dr Ambedkar and Bell Hooks. I started to visually record, rewatch, analyze and discuss my relationship with my parents (Digambar and Alka) and my then-partner (Pallavi), through the newly honed insights from my readings. This is also when my visual documentation motivated and helped me understand how our interpersonal spaces too are influenced by each of our individual intergenerational traumas within the larger casteist patriarchal world. With the similar compound lens of psychoanalysis and socio-political understanding, I started to make and see the textures of compassion and grace in my friendships beyond my kin and community through my other bodies of visual work. Currently, I am emotionally grappling with the ways to visually represent the gulf, a possible result of the difference in the ways we make sense of our personal and social positions, between me and my father.

First, I had applied for a Documentary Practice and Visual Journalism program at the International Center of Photography. I received an admit but soon realized that I may not completely avail domestic or international scholarships to make this admit a reality. Soon, my visual interests in photography had already started to shift from documenting to expressing. So, the next year, with a complete shift in my practice and intent, I reapplied at the International Center of Photography for MFA program instead. I received the admit, but both the program and scholarship opportunities stay suspended this year owing to the pandemic. As the economic anxiety to sustain and support my artistic curiosities anyway becomes my largest preoccupation lately, I also feel the need to reinvent my language and medium to coding for visuals and web development for digital curations. With a little hope left to make the access to western institutional support economically possible, I am now looking for alternative support without these economic barriers. Writing this application for Dark Study is part of responding to such rare opportunities.

*

0 notes

Text

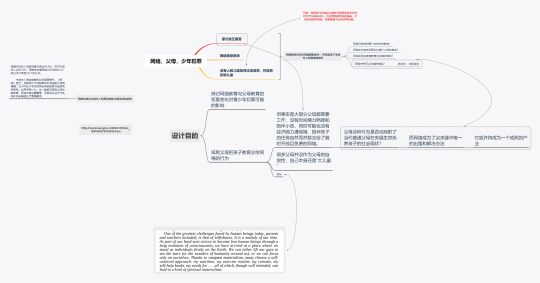

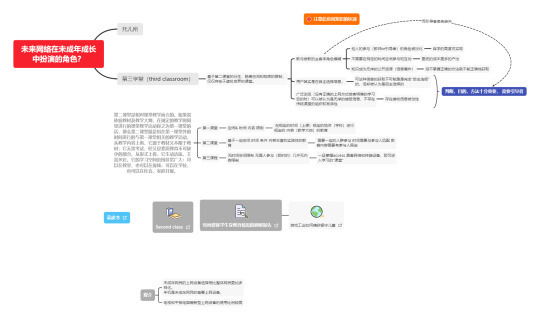

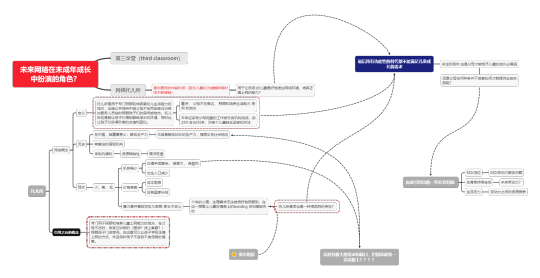

What's behind the rise in juvenile deliquency?The breaking of social bonds and the connection of networks.

This is the detailed process record of a personal design project. 2020.7.23

1.Brief

The juvenile crime rate in China has been on the rise in recent years, the rate of vicious violence is on the rise, the age of first-time offenders is declining, and the rate of left-behind children among juvenile offenders is as high as 70%...

After investigation, it is found that there are mainly two reasons behind it. First, there is a lack of education and adequate communication between parents, who do not teach their children to use the Internet properly and protect them from harmful information.Second, the network becomes accessible, and a large amount of negative information will infect the immature minds of minors in the absence of correct guidance.

The popularization and development of the network is inevitable. The Internet has become an integral part of most teenagers' lives .How to make up for the lack of guidance role, namely the lack of parental education? How to alert parents or the public to this trend?

2. Reseach process

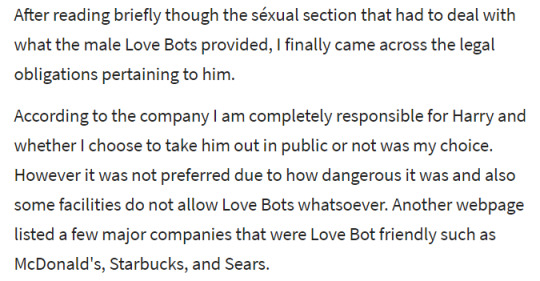

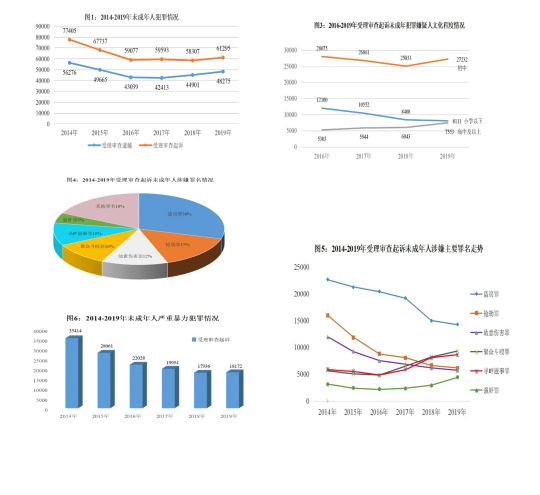

2.1 Data analysis

(Data resource: https://www.spp.gov.cn/xwfbh/wsfbt/202006/t20200601_463698.shtml#1

Research Report on Juvenile Crime in China in 2017-- Based on the comparative study of juvenile delinquents and other groups)

• From the analysis of place of residence, the juveniles living in rural areas are more likely to commit crimes

• In terms of education level, among the juvenile offenders surveyed, 26% were in primary school, 63.9% in junior middle school, 9.9% in technical secondary school or high school and 0.2% in undergraduate school.Among them, the proportion of juvenile delinquents with the educational level of junior middle schools is the highest, which is 10.4 percentage points higher than that of adult criminals.

• In terms of gender structure, the majority of juvenile delinquents are male.

• Among juvenile offenders, 97.6 % were males and 2.4 % were females.

• The main crimes committed by male minors are robbery (46.8%), intentional injury (17.5%), rape (14.5%) and theft (10.6%), etc.; • The main crime committed by female minors are drug trafficking, robbery, forced organization of prostitution, intentional injury, fraud and so on.

• The general analysis shows that male juvenile delinquents have the most types of violent crimes, while female juvenile delinquents have the characteristics of non-violent crimes

• In terms of age structure, juveniles commit crimes mainly at the age of 15 and 16.Juvenile delinquency presents a tendency of younger age.According to the 2017 survey, the average age of juvenile delinquency was 16.6 years old, while the 2013 survey showed that the average age of juvenile delinquency was 17 years old.The average age of first offence for intentional homicide is 14.1 years;The second crime was robbery, with an average age of 14.3 years.The average age of the first crime of intentional injury and rape was 14.5 years.

• Under-age offenders with lower education levels are more likely to commit crimes such as robbery, rape and intentional injury.

• The negative characteristics of male juvenile delinquents are mainly irritable, paranoid, cold, lonely and self-abasement, while the negative characteristics of female juvenile delinquents are mainly paranoid, irritable and lonely.Their contradictory physical and mental development makes their criminal behaviors show obvious impulsiveness and violence.

• Before a crime is committed, the criminal will always behave badly, is is like a sign.

Characteristics: male mainly, 15-16 year old, robberly mainly, rural areas, lower education levels, psychological illnesses, bad behavior, bad relationship with family.

2.2 Reasons behind the data

Causes of Delinquency (Travis Hirschi, 1969)

Travis Hirschi pointed out in his exploration of the causes of juvenile delinquency that everyone in society is a potential criminal,Personal and social ties can prevent individual deviance and crime, in violation of social norms when the connection is weak, the individual will commit criminal acts without constraint , as a result, crime is personal and social contact has been weakened by the weak or the result of juvenile crime is a man with traditional social contact is weak or broken. The school is primarily a personal and family social ties weakened as a result, which weakened the linkage of family school and society, social contact generally expressed through social institutions;Instead, adolescents with any external object is brought about the naissance of the moral behavior, thereby weakening the idea of the crime can be seen from the above analysis of juvenile crime, teen crime due to their physiological and psychological characteristics of maturity, determines the complexity of causes of juvenile delinquency, but no more complex, the juvenile crime reason is always inseparable from these three factors family, school and society.

Family factors have the greatest influence on minors in social ties.

2.1.1 Famliy

• Juveniles who have parents with lower education level will have more possibilities to commit crimes.

• Juceniles grow without the care of parent are morelikely to commit crimes.Only about 50 percent of juvenile delinquents live with their biological parents for a long time before they are sent to prison.

• Family discord , single parent family, domestic violencealso contributes to juvenile crime

• Left- behind chidren:In recent years, the number of juvenile crimes that have taken effect after court decisions at all levels in China has increased by about 13% annually on average. Among them, the crime rate of left-behind children accounts for about 70% of juvenile crimes, and the trend is increasing year by year.

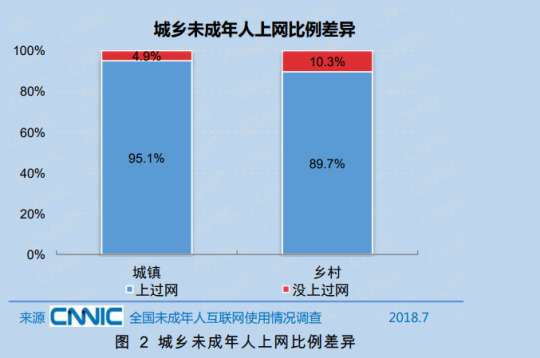

2.1.2 Media and internet

In China, the Internet penetration rate of minors is over 90%

(The disappearance of childhood, Neil Postman, 1982)

Neil postman had predict this situation in his book.Due to the popularity of the Internet and television, the knowledge generation gap between children and adults has narrowed after they have acquired language skills and basic logic ability. Children can easily access most of the knowledge that adults have access to, so children's values, preferences and activities tend to be similar to adults'.

On a macro level, the traditional bond between parents and children is weakening. A new "bond" is being formed between kids and the Internet (media, pop culture).

The social attribute of juveniles as individuals rather than family member is increasingly obvious, so the education and guidance for individuals should be paid attention to instead of relying on the correction of traditional family, community and society. Can the Internet be a tool for building bonds?Or is it toxic?

2.3 Summary

Parents have absolute control over their children.Among the factors causing juvenile delinquency, family factors are often the largest.When problems arise in the family, it is difficult for the minor to change his living and educational environment.If the parents themselves have poor management skills, such as alcoholism and domestic violence, it is almost impossible to take care of their children.

Before the crime is commited, their must some signals, eg. Hurtful to others - not at a criminal level, but with the potential to become a criminal,bad behavior,etc.

As a group with high incidence of crime, urban floating teenagers have almost gathered all the conditions and factors that may cause crime.

Personal and social ties can prevent individual deviance and crime, in violation of social norms when the connection is weak, the individual will commit criminal acts without constraint , as a result, crime is personal and social contact has been weakened by the weak or the result of juvenile crime is a man with traditional social contact is weak or broken.

The Internet has become an integral part of the life and study of minors. Although the knowledge gap between minors and adults is narrowing, there is no doubt that minors are not yet mentally mature and lack the ability to filter information, so they need to be protected.

2.4 Design Keywords

Connections: Discuss the problems with social ties among young offenders and find out the reasons behind them.

Mental health: Most young offenders have serious psychological problems. How can the public see their mental problems and help them?

Signals: Most teenagers have bad behavior before committing a crime, and in a sense, it's a distress signal, they're not sinful, they're sick, just like people sneeze when they have a cold, and their bad behavior is a way of saying they're sick and asking for help.

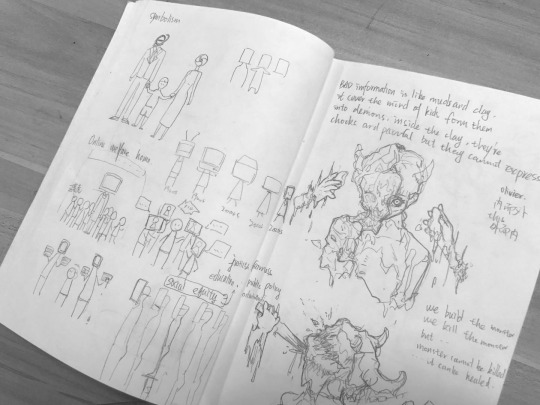

3. Ideation

3.1 Signals

Most teenagers have bad behavior before committing a crime, and in a sense, it's a distress signal, they're not sinful, they're sick, just like people sneeze when they have a cold, and their bad behavior is a way of saying they're sick and asking for help.What i will do could be a feedback system that monitoring their behavior and show the seriousness to the public.

3.2 Mental health

Most young offenders have serious psychological problems. How can the public see their mental problems and help them?It could be a mental health visulization project to directly show their psychological problems. Here is a example of mood visulazation coordinate.It may need a system like this to analysis the mental health.

3.3 Connections: Discuss the problems with social ties among young offenders and find out the reasons behind them.

Due to the popularity of the Internet and television, the knowledge generation gap between children and adults has narrowed after they have acquired language skills and basic logic ability. Children can easily access most of the knowledge that adults have access to, so children's values, preferences and activities tend to be similar to adults'.

In order to adapt to this change, should we re-examine our way of crime prevention education?

This concept will focus on the relationship among the internet, parents and children education

This direction is finally selected, and promote further.

Under This theme, I have dicussed several cocenpts that related to the family bonds, education, and internets, They indicated the trend that internet is replacing the family education in some aspect. And then I got 3 concepts: the third classroom, online nursery , digital parents.

3.3.1 3rd classroom

A vitual classroom built based on smartphone, without the limitation of time and space, which aims to help parents to protect the teens from the negative imformation from the internet , and teach them how to use it in a correct way.

When educating minors (surfing the Internet), the absence of guidance roles such as parents' and schools' leads to minors' unsatisfied demands for communication and passing of time, as well as the lack of correct information access channels, which ultimately leads to a series of negative results.

3.3.2 Online nursery

Nurseries, once a child-care facility set up to free up productivity, have fallen into disuse for a variety of reasons. Now they are making a comeback to free parents by taking care of their children while they are away, learning to surf the Internet and adapt to a rapidly changing world of information .

3.3.2 Digital parents

This is finally selected and detailed shown in 4.0.

4.0 Preliminary conception

This is developed based on the keyword ‘connection’.

Old connection broke, new connection is being constructed.

What if parents were totally replaced by the Internet?

In resent years, because of work pressure and many other reasons, many parents don't have enough time to accompany the education of children, children gain lot of information through the Internet access, but the network information is very complex and diverse, without a correct leading to the child's access to the internet, it will produce subtle bad influence. To some extent, parents to accompany children education relies on the network world.

In this project, I hope that parents can realize the seriousness of this problem, so as to increase offline companionship.

The project intends to make the point where parents rely on the Internet world for education and companionship to the extreme, so that parents can realize that their current behavior is actually gradually developing in this direction.The essence of the project is future design and ironic design.

In this era of Internet +, this project proposes the possibility of Internet + family education. It is an imaginary network service that can completely replace parents to perform the obligations of supervision and education to guide children's entertainment, life and learning in their spare time and input values and knowledge. This project is to extreme the situation that parents entrust their children's education to the Internet . It is an absurd and ironic branding. Through ironic prophecy, it will tell parents to take responsibilities and pay more attention to their children's growth and education.

2020.7.25

0 notes

Text

VIRTUAL AND OTHER BODIES by mark wilsher

We need a new language of embodiment for 3D technologies argues Mark Wilsher. The unnerving feelings of dissociation triggered by the works of artists such as Oliver Laric, Laurie Anderson and Rachel Rossin show that, if we are to spend more time in the virtual world, it is important not to leave the body behind.

[P]retty much every image in three-dimensions was destined to remain as just that, an image. The irony of the huge explosion in 3D is that the vast majority of the models are built to be seen on 2D screens. Within video games and the media, a fully realised model is often simply a more efficient way to create flat animations, allowing the software to crunch the numbers to simulate the perspective and parallax. The same is true to contemporary art where we are becoming used to seeing complex forms presented to us via the screen. They might be 3D in one sense, but in reality we approach them pictorially [...] For [Clement Greenberg, 60 years ago,] materiality, mass and gravity were things to be transcended rather than savoured. The illusion of weightlessness and movement were important to [him], with welded steel becoming ‘a picture in three-dimensional space’. [...] [This interpretation] is typical of the immaterial and primarily visual landscape to be found within cyberspace.

[...] Clearly, however, when attempting to force a sculptural reading onto contemporary 3D computer models, the essential problem is their fundamental lack of physicality. There is no ‘material’ beyond data. There is no substance, just an image on the screen. Two important and related effects result from this absence. The first is that, for as long as they remain held purely within the computer, 3D models do not have any relationship with the idea of scale. [...] The virtual space you are operating in has no connection to real space as experienced by a human being. It is much closer to the mathematician and philosopher Henri Poincaré’s description of ‘geometric space’ as continuous, homogeneous and infinite, an abstract representation of the three dimensions of real space that is most suited to handling coordinates and geometric constructions. The ability to see at any scale, to navigate without friction between one view and another, to manipulate an object or a world so easily, might also remind us of Donna Haraway’s description of patriarchal scientific vision: ‘the god-trick of seeing everything from nowhere’. [...] the point being that the tools of scientific vision enable an apparent freedom of movement between scales and positions that claim objectivity, but in fact efface their makers’ own subjectivity in the name of authority.

[...] This leads to the second important effect of data’s lack of material presence. There is absolutely no relationship between the object being modelled and the human body, no relationship to the body of the audience sitting of the other side of the screen, and no relationship to the body of the artist throughout the process of making. [...] The scale of a piece, the arrangement of its parts, even the marks inscribed on its surface all ultimately derive from an anthropomorphic relationship with its maker. None of this is true of the new forms being made in 3D today.

[American artist Rachel Rossin] was describing the dissociated sensation caused by spending a long time in another place: ‘I was recalling the memory of what having a body was like. In VR you feel like the memory of a body, the emotional memory of a body.’ [...] For [Laurie] Anderson, [being bodiless] is a welcome experience of freedom, or perhaps one of total absorption into a technologically mediated universe. But it underlines the point that virtual reality is an essentially disembodied medium, which may promise to be as good as real reality while lacking everything about human experience other than the purely optical.

[...] No matter what the content, no matter who the programmer, a virtual space created purely from data and navigable without any relationship to our situated bodies will always represent a patriarchal mode of experience because it is ultimately a dissociated one. It denies the body in order to more easily colonise space.

[...] It may also be significant that one of the mind’s primary response to experiencing trauma is to dissociate from the body. We are seeing an epidemic in anxiety and dissociative mental health conditions among young people at present, which many link to the universal immersion in digital and virtual spaces online. The connections to cultural phenomena such as social media are well understood now, but I would suggest a more fundamental, phenomenological link to the disembodied experience of a purely geometric space must also have an effect. It does not feel good to leave your body behind.

[...] The vogue for post-internet art may well have dissipated but 3D technologies will play an increasingly normal part within contemporary art in years to come, as signalled by the inclusion of a virtual/augmented reality section in last month’s Frieze New York. What is needed is to develop a new vocabulary for dealing with virtual forms that goes beyond the simple contradictions of presence and absence, original and copy. I would like to see the human body somewhere near the centre of such a vocabulary.

0 notes

Text

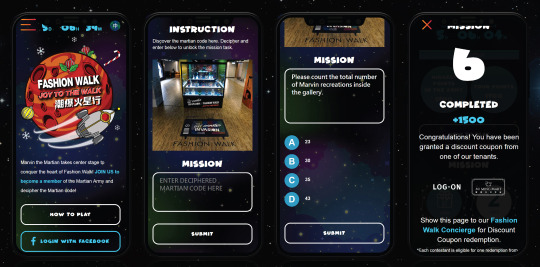

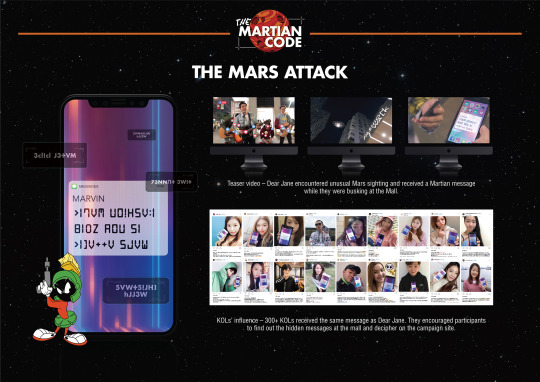

In recent times, increasingly more campaign descriptions include claims that some form of gaming is being exploited. What value is just above the value of the word in the Hong Kong advertising picture? Rick Increase speaks with two businesses which have gained its awards

Recreation Guidelines

“I really don't think gaming is something new in APAC or the world,” says CEO Penny Chow Reprise in HK