#LONG BEARD ARTHUR ANTI

Text

do you guys ever see an arthur thats just. not how the arthur in your mind is supposed to be at all and its not like the arthur owner did anything bad its just wrong

#LONG BEARD ARTHUR ANTI#i do not care if you disagree#like its alright if its a little long but santa claus arthur is tremndous#saw a friend with santa arthur and i was like#why#arthur morgan#rdr2#dc speaks!!#red dead redemption 2

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the sky

Glasgow-Dubai-Jakarta

25th - 26th September 2022

Warning: this letter may be overly dramatic and sentimental :")

Dear Alberto,

When I wrote this letter, all that I could see from the plane window were the blue sky and white cotton candy clouds. I'm such a crybaby it made the nice guy sitting next to me look worried. He's from Czech, cannot speak English but was very kind. He offered me tissue and chocolate cookies.

Being on the plane has made me remember the boredom I experienced on my flight to Glasgow, a year ago. It was my first long-haul flight and the farthest I went away from home. I felt relieved when finally stepped on the ground, but that was before being greeted by the rude strong Glaschu's wind. Thus, being the clueless girl I am, I had no idea what my life will be like in Glasgow for a year. I guess I have done quite well, and one of the highlights of the year is my encounter with a certain curly guy.

It will be anti-climax and twisted if then I say that the man's name is Alejandro or Gaston Castano. But noo, the man's name is Alberto.

I still remember the first time I saw you, in the hallway to the kitchen. You showed up from your door, I bet were in the middle of studying of course, and said hi to me! A bearded face, long curly hair and that warm big smile! After that first encounter, I met you in the kitchen. I thought (and still thinking) that you are a very interesting person. You told me that you are "crazy about waves" when we talked about Bali. Then you showed me the pictures of you and your brothers. Wow, what a warm sibling relationship, that's what I thought. And then you shared the delicious chicken tomato pasta! As time went by, we would not only share food but stories too.

I am happy somehow that we have passed the common nice and proper courtesy of a new neighbour, into more silly but fun daily interactions! Being silly feel so easy with you. I guess sharing movie nights, cool playlists, fighting over dishes and bad cookies, lost in the mountain during heatwaves, and hiking Arthur's seat in the middle of water-ice rains did that to us? And I know sometimes it's not always rainbow-and-butterflies stories, but I guess that's just how life goes on. Still, it's so good to have the finest person ever to pick up all of the lemons that life throws at us. Then cut them in half to taste, or just carelessly throw away all of the lemon back.

Thus I am not sure when it started, but the dinner time, movie nights, the door-knock game and just everything had become my daily routine. I would come to the flat after a long day and be thinking of so many prank ideas when saw your old blue bike parked in front of the building. But then you sold your bike before I could do my plans.

Well, I can say that I admire how you always showed that you feel content and enough with yourself. And very passionate about something you like. I really love to hear you telling me stories about surfing, math, physics, books, and just anything. Those were some of the many things I learnt from you. Somehow it made me realize what things that missing from my life, a simple joy in doing something I really love. So I am lucky to meet someone who reminds me of how to properly live my life again. Maybe I should stop now before this letter turns out to be too corny.

The more I write, the more I realize how far away this plane taking me from Glasgow, where you are right now.

So, allow me to say, it is such a pleasure to know you on this journey! I definitely won't have it any other way. And I am sure our paths will cross again! And we will eat sour peaches together again! And spicy foods until your face turns all red!

Take care of yourself!

Lusi

0 notes

Text

The Green Knight and Medieval Metatextuality: An Essay

Right, so. Finally watched it last night, and I’ve been thinking about it literally ever since, except for the part where I was asleep. As I said to fellow medievalist and admirer of Dev Patel @oldshrewsburyian, it’s possibly the most fascinating piece of medieval-inspired media that I’ve seen in ages, and how refreshing to have something in this genre that actually rewards critical thought and deep analysis, rather than me just fulminating fruitlessly about how popular media thinks that slapping blood, filth, and misogyny onto some swords and castles is “historically accurate.” I read a review of TGK somewhere that described it as the anti-Game of Thrones, and I’m inclined to think that’s accurate. I didn’t agree with all of the film’s tonal, thematic, or interpretative choices, but I found them consistently stylish, compelling, and subversive in ways both small and large, and I’m gonna have to write about it or I’ll go crazy. So. Brace yourselves.

(Note: My PhD is in medieval history, not medieval literature, and I haven’t worked on SGGK specifically, but I am familiar with it, its general cultural context, and the historical influences, images, and debates that both the poem and the film referenced and drew upon, so that’s where this meta is coming from.)

First, obviously, while the film is not a straight-up text-to-screen version of the poem (though it is by and large relatively faithful), it is a multi-layered meta-text that comments on the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the archetypes of chivalric literature as a whole, modern expectations for medieval films, the hero’s journey, the requirements of being an “honorable knight,” and the nature of death, fate, magic, and religion, just to name a few. Given that the Arthurian legendarium, otherwise known as the Matter of Britain, was written and rewritten over several centuries by countless authors, drawing on and changing and hybridizing interpretations that sometimes challenged or outright contradicted earlier versions, it makes sense for the film to chart its own path and make its own adaptational decisions as part of this multivalent, multivocal literary canon. Sir Gawain himself is a canonically and textually inconsistent figure; in the movie, the characters merrily pronounce his name in several different ways, most notably as Sean Harris/King Arthur’s somewhat inexplicable “Garr-win.” He might be a man without a consistent identity, but that’s pointed out within the film itself. What has he done to define himself, aside from being the king’s nephew? Is his quixotic quest for the Green Knight actually going to resolve the question of his identity and his honor – and if so, is it even going to matter, given that successful completion of the “game” seemingly equates with death?

Likewise, as the anti-Game of Thrones, the film is deliberately and sometimes maddeningly non-commercial. For an adaptation coming from a studio known primarily for horror, it almost completely eschews the cliché that gory bloodshed equals authentic medievalism; the only graphic scene is the Green Knight’s original beheading. The violence is only hinted at, subtextual, suspenseful; it is kept out of sight, around the corner, never entirely played out or resolved. In other words, if anyone came in thinking that they were going to watch Dev Patel luridly swashbuckle his way through some CGI monsters like bad Beowulf adaptations of yore, they were swiftly disappointed. In fact, he seems to spend most of his time being wet, sad, and failing to meet the moment at hand (with a few important exceptions).

The film unhurriedly evokes a medieval setting that is both surreal and defiantly non-historical. We travel (in roughly chronological order) from Anglo-Saxon huts to Romanesque halls to high-Gothic cathedrals to Tudor villages and half-timbered houses, culminating in the eerie neo-Renaissance splendor of the Lord and Lady’s hall, before returning to the ancient trees of the Green Chapel and its immortal occupant: everything that has come before has now returned to dust. We have been removed even from imagined time and place and into a moment where it ceases to function altogether. We move forward, backward, and sideways, as Gawain experiences past, present, and future in unison. He is dislocated from his own sense of himself, just as we, the viewers, are dislocated from our sense of what is the “true” reality or filmic narrative; what we think is real turns out not to be the case at all. If, of course, such a thing even exists at all.

This visual evocation of the entire medieval era also creates a setting that, unlike GOT, takes pride in rejecting absolutely all political context or Machiavellian maneuvering. The film acknowledges its own cultural ubiquity and the question of whether we really need yet another King Arthur adaptation: none of the characters aside from Gawain himself are credited by name. We all know it’s Arthur, but he’s listed only as “king.” We know the spooky druid-like old man with the white beard is Merlin, but it’s never required to spell it out. The film gestures at our pre-existing understanding; it relies on us to fill in the gaps, cuing us to collaboratively produce the story with it, positioning us as listeners as if we were gathered to hear the original poem. Just like fanfiction, it knows that it doesn’t need to waste time introducing every single character or filling in ultimately unnecessary background knowledge, when the audience can be relied upon to bring their own.

As for that, the film explicitly frames itself as a “filmed adaptation of the chivalric romance” in its opening credits, and continues to play with textual referents and cues throughout: telling us where we are, what’s happening, or what’s coming next, rather like the rubrics or headings within a medieval manuscript. As noted, its historical/architectural references span the entire medieval European world, as does its costume design. I was particularly struck by the fact that Arthur and Guinevere’s crowns resemble those from illuminated monastic manuscripts or Eastern Orthodox iconography: they are both crown and halo, they confer an air of both secular kingship and religious sanctity. The question in the film’s imagined epilogue thus becomes one familiar to Shakespeare’s Henry V: heavy is the head that wears the crown. Does Gawain want to earn his uncle’s crown, take over his place as king, bear the fate of Camelot, become a great ruler, a husband and father in ways that even Arthur never did, only to see it all brought to dust by his cowardice, his reliance on unscrupulous sorcery, and his unfulfilled promise to the Green Knight? Is it better to have that entire life and then lose it, or to make the right choice now, even if it means death?

Likewise, Arthur’s kingly mantle is Byzantine in inspiration, as is the icon of the Virgin Mary-as-Theotokos painted on Gawain’s shield (which we see broken apart during the attack by the scavengers). The film only glances at its religious themes rather than harping on them explicitly; we do have the cliché scene of the male churchmen praying for Gawain’s safety, opposite Gawain’s mother and her female attendants working witchcraft to protect him. (When oh when will I get my film that treats medieval magic and medieval religion as the complementary and co-existing epistemological systems that they were, rather than portraying them as diametrically binary and disparagingly gendered opposites?) But despite the interim setbacks borne from the failure of Christian icons, the overall resolution of the film could serve as the culmination of a medieval Christian morality tale: Gawain can buy himself a great future in the short term if he relies on the protection of the enchanted green belt to avoid the Green Knight’s killing stroke, but then he will have to watch it all crumble until he is sitting alone in his own hall, his children dead and his kingdom destroyed, as a headless corpse who only now has been brave enough to accept his proper fate. By removing the belt from his person in the film’s Inception-like final scene, he relinquishes the taint of black magic and regains his religious honor, even at the likely cost of death. That, the medieval Christian morality tale would agree, is the correct course of action.

Gawain’s encounter with St. Winifred likewise presents a more subtle vision of medieval Christianity. Winifred was an eighth-century Welsh saint known for being beheaded, after which (by the power of another saint) her head was miraculously restored to her body and she went on to live a long and holy life. It doesn’t quite work that way in TGK. (St Winifred’s Well is mentioned in the original SGGK, but as far as I recall, Gawain doesn’t meet the saint in person.) In the film, Gawain encounters Winifred’s lifelike apparition, who begs him to dive into the mere and retrieve her head (despite appearances, she warns him, it is not attached to her body). This fits into the pattern of medieval ghost stories, where the dead often return to entreat the living to help them finish their business; they must be heeded, but when they are encountered in places they shouldn’t be, they must be put back into their proper physical space and reminded of their real fate. Gawain doesn’t follow William of Newburgh’s practical recommendation to just fetch some brawny young men with shovels to beat the wandering corpse back into its grave. Instead, in one of his few moments of unqualified heroism, he dives into the dark water and retrieves Winifred’s skull from the bottom of the lake. Then when he returns to the house, he finds the rest of her skeleton lying in the bed where he was earlier sleeping, and carefully reunites the skull with its body, finally allowing it to rest in peace.

However, Gawain’s involvement with Winifred doesn’t end there. The fox that he sees on the bank after emerging with her skull, who then accompanies him for the rest of the film, is strongly implied to be her spirit, or at least a companion that she has sent for him. Gawain has handled a saint’s holy bones; her relics, which were well known to grant protection in the medieval world. He has done the saint a service, and in return, she extends her favor to him. At the end of the film, the fox finally speaks in a human voice, warning him not to proceed to the fateful final encounter with the Green Knight; it will mean his death. The symbolism of having a beheaded saint serve as Gawain’s guide and protector is obvious, since it is the fate that may or may not lie in store for him. As I said, the ending is Inception-like in that it steadfastly refuses to tell you if the hero is alive (or will live) or dead (or will die). In the original SGGK, of course, the Green Knight and the Lord turn out to be the same person, Gawain survives, it was all just a test of chivalric will and honor, and a trap put together by Morgan Le Fay in an attempt to frighten Guinevere. It’s essentially able to be laughed off: a game, an adventure, not real. TGK takes this paradigm and flips it (to speak…) on its head.

Gawain’s rescue of Winifred’s head also rewards him in more immediate terms: his/the Green Knight’s axe, stolen by the scavengers, is miraculously restored to him in her cottage, immediately and concretely demonstrating the virtue of his actions. This is one of the points where the film most stubbornly resists modern storytelling conventions: it simply refuses to add in any kind of “rational” or “empirical” explanation of how else it got there, aside from the grace and intercession of the saint. This is indeed how it works in medieval hagiography: things simply reappear, are returned, reattached, repaired, made whole again, and Gawain’s lost weapon is thus restored, symbolizing that he has passed the test and is worthy to continue with the quest. The film’s narrative is not modernizing its underlying medieval logic here, and it doesn’t particularly care if a modern audience finds it “convincing” or not. As noted, the film never makes any attempt to temporalize or localize itself; it exists in a determinedly surrealist and ahistorical landscape, where naked female giants who look suspiciously like Tilda Swinton roam across the wild with no necessary explanation. While this might be frustrating for some people, I actually found it a huge relief that a clearly fantastic and fictional literary adaptation was not acting like it was qualified to teach “real history” to its audience. Nobody would come out of TGK thinking that they had seen the “actual” medieval world, and since we have enough of a problem with that sort of thing thanks to GOT, I for one welcome the creation of a medieval imaginative space that embraces its eccentric and unrealistic elements, rather than trying to fit them into the Real Life box.

This plays into the fact that the film, like a reused medieval manuscript containing more than one text, is a palimpsest: for one, it audaciously rewrites the entire Arthurian canon in the wordless vision of Gawain’s life after escaping the Green Knight (I could write another meta on that dream-epilogue alone). It moves fluidly through time and creates alternate universes in at least two major points: one, the scene where Gawain is tied up and abandoned by the scavengers and that long circling shot reveals his skeletal corpse rotting on the sward, only to return to our original universe as Gawain decides that he doesn’t want that fate, and two, Gawain as King. In this alternate ending, Arthur doesn’t die in battle with Mordred, but peaceably in bed, having anointed his worthy nephew as his heir. Gawain becomes king, has children, gets married, governs Camelot, becomes a ruler surpassing even Arthur, but then watches his son get killed in battle, his subjects turn on him, and his family vanish into the dust of his broken hall before he himself, in despair, pulls the enchanted scarf out of his clothing and succumbs to his fate.

In this version, Gawain takes on the responsibility for the fall of Camelot, not Arthur. This is the hero’s burden, but he’s obtained it dishonorably, by cheating. It is a vivid but mimetic future which Gawain (to all appearances) ultimately rejects, returning the film to the realm of traditional Arthurian canon – but not quite. After all, if Gawain does get beheaded after that final fade to black, it would represent a significant alteration from the poem and the character’s usual arc. Are we back in traditional canon or aren’t we? Did Gawain reject that future or didn’t he? Do all these alterities still exist within the visual medium of the meta-text, and have any of them been definitely foreclosed?

Furthermore, the film interrogates itself and its own tropes in explicit and overt ways. In Gawain’s conversation with the Lord, the Lord poses the question that many members of the audience might have: is Gawain going to carry out this potentially pointless and suicidal quest and then be an honorable hero, just like that? What is he actually getting by staggering through assorted Irish bogs and seeming to reject, rather than embrace, the paradigms of a proper quest and that of an honorable knight? He lies about being a knight to the scavengers, clearly out of fear, and ends up cravenly bound and robbed rather than fighting back. He denies knowing anything about love to the Lady (played by Alicia Vikander, who also plays his lover at the start of the film with a decidedly ropey Yorkshire accent, sorry to say). He seems to shrink from the responsibility thrust on him, rather than rise to meet it (his only honorable act, retrieving Winifred’s head, is discussed above) and yet here he still is, plugging away. Why is he doing this? What does he really stand to gain, other than accepting a choice and its consequences (somewhat?) The film raises these questions, but it has no plans to answer them. It’s going to leave you to think about them for yourself, and it isn’t going to spoon-feed you any ultimate moral or neat resolution. In this interchange, it’s easy to see both the echoes of a formal dialogue between two speakers (a favored medieval didactic tactic) and the broader purpose of chivalric literature: to interrogate what it actually means to be a knight, how personal honor is generated, acquired, and increased, and whether engaging in these pointless and bloody “war games” is actually any kind of real path to lasting glory.

The film’s treatment of race, gender, and queerness obviously also merits comment. By casting Dev Patel, an Indian-born actor, as an Arthurian hero, the film is… actually being quite accurate to the original legends, doubtless much to the disappointment of assorted internet racists. The thirteenth-century Arthurian romance Parzival (Percival) by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach notably features the character of Percival’s mixed-race half-brother, Feirefiz, son of their father by his first marriage to a Muslim princess. Feirefiz is just as heroic as Percival (Gawaine, for the record, also plays a major role in the story) and assists in the quest for the Holy Grail, though it takes his conversion to Christianity for him to properly behold it.

By introducing Patel (and Sarita Chowdhury as Morgause) to the visual representation of Arthuriana, the film quietly does away with the “white Middle Ages” cliché that I have complained about ad nauseam; we see background Asian and black members of Camelot, who just exist there without having to conjure up some complicated rationale to explain their presence. The Lady also uses a camera obscura to make Gawain’s portrait. Contrary to those who might howl about anachronism, this technique was known in China as early as the fourth century BCE and the tenth/eleventh century Islamic scholar Ibn al-Haytham was probably the best-known medieval authority to write on it extensively; Latin translations of his work inspired European scientists from Roger Bacon to Leonardo da Vinci. Aside from the symbolism of an upside-down Gawain (and when he sees the portrait again during the ‘fall of Camelot’, it is right-side-up, representing that Gawain himself is in an upside-down world), this presents a subtle challenge to the prevailing Eurocentric imagination of the medieval world, and draws on other global influences.

As for gender, we have briefly touched on it above; in the original SGGK, Gawain’s entire journey is revealed to be just a cruel trick of Morgan Le Fay, simply trying to destabilize Arthur’s court and upset his queen. (Morgan is the old blindfolded woman who appears in the Lord and Lady’s castle and briefly approaches Gawain, but her identity is never explicitly spelled out.) This is, obviously, an implicitly misogynistic setup: an evil woman plays a trick on honorable men for the purpose of upsetting another woman, the honorable men overcome it, the hero survives, and everyone presumably lives happily ever after (at least until Mordred arrives).

Instead, by plunging the outcome into doubt and the hero into a much darker and more fallible moral universe, TGK shifts the blame for Gawain’s adventure and ultimate fate from Morgan to Gawain himself. Likewise, Guinevere is not the passive recipient of an evil deception but in a way, the catalyst for the whole thing. She breaks the seal on the Green Knight’s message with a weighty snap; she becomes the oracle who reads it out, she is alarming rather than alarmed, she disrupts the complacency of the court and silently shows up all the other knights who refuse to step forward and answer the Green Knight’s challenge. Gawain is not given the ontological reassurance that it’s just a practical joke and he’s going to be fine (and thanks to the unresolved ending, neither are we). The film instead takes the concept at face value in order to push the envelope and ask the simple question: if a man was going to be actually-for-real beheaded in a year, why would he set out on a suicidal quest? Would you, in Gawain’s place, make the same decision to cast aside the enchanted belt and accept your fate? Has he made his name, will he be remembered well? What is his legacy?

Indeed, if there is any hint of feminine connivance and manipulation, it arrives in the form of the implication that Gawain’s mother has deliberately summoned the Green Knight to test her son, prove his worth, and position him as his childless uncle’s heir; she gives him the protective belt to make sure he won’t actually die, and her intention all along was for the future shown in the epilogue to truly play out (minus the collapse of Camelot). Only Gawain loses the belt thanks to his cowardice in the encounter with the scavengers, regains it in a somewhat underhanded and morally questionable way when the Lady is attempting to seduce him, and by ultimately rejecting it altogether and submitting to his uncertain fate, totally mucks up his mother’s painstaking dynastic plans for his future. In this reading, Gawain could be king, and his mother’s efforts are meant to achieve that goal, rather than thwart it. He is thus required to shoulder his own responsibility for this outcome, rather than conveniently pawning it off on an “evil woman,” and by extension, the film asks the question: What would the world be like if men, especially those who make war on others as a way of life, were actually forced to face the consequences of their reckless and violent actions? Is it actually a “game” in any sense of the word, especially when chivalric literature is constantly preoccupied with the question of how much glorious violence is too much glorious violence? If you structure social prestige for the king and the noble male elite entirely around winning battles and existing in a state of perpetual war, when does that begin to backfire and devour the knightly class – and the rest of society – instead?

This leads into the central theme of Gawain’s relationships with the Lord and Lady, and how they’re treated in the film. The poem has been repeatedly studied in terms of its latent (and sometimes… less than latent) queer subtext: when the Lord asks Gawain to pay back to him whatever he should receive from his wife, does he already know what this involves; i.e. a physical and romantic encounter? When the Lady gives kisses to Gawain, which he is then obliged to return to the Lord as a condition of the agreement, is this all part of a dastardly plot to seduce him into a kinky green-themed threesome with a probably-not-human married couple looking to spice up their sex life? Why do we read the Lady’s kisses to Gawain as romantic but Gawain’s kisses to the Lord as filial, fraternal, or the standard “kiss of peace” exchanged between a liege lord and his vassal? Is Gawain simply being a dutiful guest by honoring the bargain with his host, actually just kissing the Lady again via the proxy of her husband, or somewhat more into this whole thing with the Lord than he (or the poet) would like to admit? Is the homosocial turning homoerotic, and how is Gawain going to navigate this tension and temptation?

If the question is never resolved: well, welcome to one of the central medieval anxieties about chivalry, knighthood, and male bonds! As I have written about before, medieval society needed to simultaneously exalt this as the most honored and noble form of love, and make sure it didn’t accidentally turn sexual (once again: how much male love is too much male love?). Does the poem raise the possibility of serious disruption to the dominant heteronormative paradigm, only to solve the problem by interpreting the Gawain/Lady male/female kisses as romantic and sexual and the Gawain/Lord male/male kisses as chaste and formal? In other words, acknowledging the underlying anxiety of possible homoeroticism but ultimately reasserting the heterosexual norm? The answer: Probably?!?! Maybe?!?! Hell if we know??! To say the least, this has been argued over to no end, and if you locked a lot of medieval history/literature scholars into a room and told them that they couldn’t come out until they decided on one clear answer, they would be in there for a very long time. The poem seemingly invokes the possibility of a queer reading only to reject it – but once again, as in the question of which canon we end up in at the film’s end, does it?

In some lights, the film’s treatment of this potential queer reading comes off like a cop-out: there is only one kiss between Gawain and the Lord, and it is something that the Lord has to initiate after Gawain has already fled the hall. Gawain himself appears to reject it; he tells the Lord to let go of him and runs off into the wilderness, rather than deal with or accept whatever has been suggested to him. However, this fits with film!Gawain’s pattern of rejecting that which fundamentally makes him who he is; like Peter in the Bible, he has now denied the truth three times. With the scavengers he denies being a knight; with the Lady he denies knowing about courtly love; with the Lord he denies the central bond of brotherhood with his fellows, whether homosocial or homoerotic in nature. I would go so far as to argue that if Gawain does die at the end of the film, it is this rejected kiss which truly seals his fate. In the poem, the Lord and the Green Knight are revealed to be the same person; in the film, it’s not clear if that’s the case, or they are separate characters, even if thematically interrelated. If we assume, however, that the Lord is in fact still the human form of the Green Knight, then Gawain has rejected both his kiss of peace (the standard gesture of protection offered from lord to vassal) and any deeper emotional bond that it can be read to signify. The Green Knight could decide to spare Gawain in recognition of the courage he has shown in relinquishing the enchanted belt – or he could just as easily decide to kill him, which he is legally free to do since Gawain has symbolically rejected the offer of brotherhood, vassalage, or knight-bonding by his unwise denial of the Lord’s freely given kiss. Once again, the film raises the overall thematic and moral question and then doesn’t give one straight (ahem) answer. As with the medieval anxieties and chivalric texts that it is based on, it invokes the specter of queerness and then doesn’t neatly resolve it. As a modern audience, we find this unsatisfying, but once again, the film is refusing to conform to our expectations.

As has been said before, there is so much kissing between men in medieval contexts, both ceremonial and otherwise, that we’re left to wonder: “is it gay or is it feudalism?” Is there an overtly erotic element in Gawain and the Green Knight’s mutual “beheading” of each other (especially since in the original version, this frees the Lord from his curse, functioning like a true love’s kiss in a fairytale). While it is certainly possible to argue that the film has “straightwashed” its subject material by removing the entire sequence of kisses between Gawain and the Lord and the unresolved motives for their existence, it is a fairly accurate, if condensed, representation of the anxieties around medieval knightly bonds and whether, as Carolyn Dinshaw put it, a (male/male) “kiss is just a kiss.” After all, the kiss between Gawain and the Lady is uncomplicatedly read as sexual/romantic, and that context doesn’t go away when Gawain is kissing the Lord instead. Just as with its multiple futurities, the film leaves the question open-ended. Is it that third and final denial that seals Gawain’s fate, and if so, is it asking us to reflect on why, specifically, he does so?

The film could play with both this question and its overall tone quite a bit more: it sometimes comes off as a grim, wooden, over-directed Shakespearean tragedy, rather than incorporating the lively and irreverent tone that the poem often takes. It’s almost totally devoid of humor, which is unfortunate, and the Grim Middle Ages aesthetic is in definite evidence. Nonetheless, because of the comprehensive de-historicizing and the obvious lack of effort to claim the film as any sort of authentic representation of the medieval past, it works. We are not meant to understand this as a historical document, and so we have to treat it on its terms, by its own logic, and by its own frames of reference. In some ways, its consistent opacity and its refusal to abide by modern rules and common narrative conventions is deliberately meant to challenge us: as before, when we recognize Arthur, Merlin, the Round Table, and the other stock characters because we know them already and not because the film tells us so, we have to fill in the gaps ourselves. We are watching the film not because it tells us a simple adventure story – there is, as noted, shockingly little action overall – but because we have to piece together the metatext independently and ponder the philosophical questions that it leaves us with. What conclusion do we reach? What canon do we settle in? What future or resolution is ultimately made real? That, the film says, it can’t decide for us. As ever, it is up to future generations to carry on the story, and decide how, if at all, it is going to survive.

(And to close, I desperately want them to make my much-coveted Bisclavret adaptation now in more or less the same style, albeit with some tweaks. Please.)

Further Reading

Ailes, Marianne J. ‘The Medieval Male Couple and the Language of Homosociality’, in Masculinity in Medieval Europe, ed. by Dawn M. Hadley (Harlow: Longman, 1999), pp. 214–37.

Ashton, Gail. ‘The Perverse Dynamics of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 15 (2005), 51–74.

Boyd, David L. ‘Sodomy, Misogyny, and Displacement: Occluding Queer Desire in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Arthuriana 8 (1998), 77–113.

Busse, Peter. ‘The Poet as Spouse of his Patron: Homoerotic Love in Medieval Welsh and Irish Poetry?’, Studi Celtici 2 (2003), 175–92.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. ‘A Kiss Is Just a Kiss: Heterosexuality and Its Consolations in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, Diacritics 24 (1994), 205–226.

Kocher, Suzanne. ‘Gay Knights in Medieval French Fiction: Constructs of Queerness and Non-Transgression’, Mediaevalia 29 (2008), 51–66.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. ‘Knighthood, Compulsory Heterosexuality, and Sodomy’ in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 273–86.

Kuefler, Matthew. ‘Male Friendship and the Suspicion of Sodomy in Twelfth-Century France’, in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Matthew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 179–214.

McVitty, E. Amanda, ‘False Knights and True Men: Contesting Chivalric Masculinity in English Treason Trials, 1388–1415,’ Journal of Medieval History 40 (2014), 458–77.

Mieszkowski, Gretchen. ‘The Prose Lancelot's Galehot, Malory's Lavain, and the Queering of Late Medieval Literature’, Arthuriana 5 (1995), 21–51.

Moss, Rachel E. ‘ “And much more I am soryat for my good knyghts’ ”: Fainting, Homosociality, and Elite Male Culture in Middle English Romance’, Historical Reflections / Réflexions historiques 42 (2016), 101–13.

Zeikowitz, Richard E. ‘Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes’, College English 65 (2002), 67–80.

#the green knight#the green knight meta#sir gawain and the green knight#medieval literature#medieval history#this meta is goddamn 5.2k words#and has its own reading list#i uh#said i had a lot of thoughts?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

My RDR2 Themed Userboxes

This user loves __

This user loves Arthur and John's relationship

This user loves Arthur Morgan

This user loves Arthur Morgan's long hair and beard

This user loves Charles Smith

This user loves Dutch Van Der Linde

This user loves Hamish Sinclair

This user loves Hosea Matthews

This user loves Javier Escuella

This user loves Jack Marston

This user loves John Marston

This user loves Lenny Summers

This user loves the Marstons

This user loves Mary-Beth Gaskill

This user loves Molly O'Shea

This user loves Sadie Adler

This user loves Sean Maguire

This user loves Susan Grimshaw

This user loves Tilly Jackson

This user loves Uncle

This user ships __

This user ships Charthur

This user ships Vandermatthews

This user __ (chapter related)

This user doesn't play past chapter 3

This user's least favourite chapter was chapter 5

This user's favourite chapter is chapter 2

This user's favourite __ is __ (missions)

This user's favourite mission is A Quiet Time

This user's favourite mission is Advertising, The New American Art

This user's favourite mission is Exit, Persued By A Bruised Ego

This user's favourite mission is The Aftermath of Genesis

This user's favourite __ is __ (horses)

This user's favourite horse is the black raven shire

This user's favourite horse is Buell

This user's favourite horse is the warped brindle arabian

This user’s favourite horse is is the dapple dark grey hungarian half bred

This user's favourite horse is the mahogany bay tennessee walker

This user's favourite __ is __ (towns)

This user's favourite town is Blackwater

This user's favourite town is Valentine

This user __ (miscellaneous)

This user would sell Micah Bell to Satan for a single corn chip

This user wants nothing more than to see Dutch choke on a fat fucking mango

This user believes Kieran Duffy deserved better

This user can't get enough of Arthur and Hosea's relationship

This user wants to write RDR2 fanfics but doesn't know where to start

This user wishes everyone a happy Hosea Snores Saturday

This user doesn't want anti Morston/Vandermorgan users interacting with their blog

This user's feelings about Dutch Van Der Linde fluctuate a LOT

This user's favourite song from the RDR2 soundtrack is Crash Of Worlds

This user misses Hosea Matthews

This user wishes Arthur could pet cats

This user's comfort game is Red Dead Redemption 2

Feel free to send in some more requests. This will (hopefully) be updated every time I make some new ones :)

#rdr#red dead#rdr fandom#red dead fandom#red dead 2#rdr2#rdr2 fandom#red dead redemption 2#kieran duffy#micah bell#dutch van der linde#arthur morgan#javier escuella#john marston#charthur#vandermatthews#tilly jackson#hosea matthews#charles smith

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

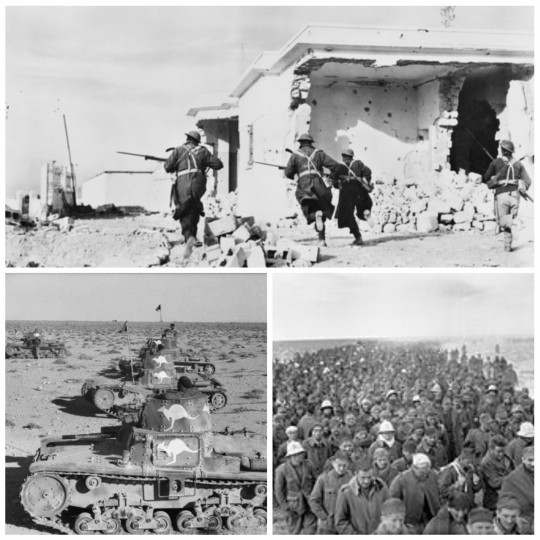

• Battle of Bardia

The Battle of Bardia was fought between January 3rd and 5th 1941, as part of Operation Compass, the first British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War.

Italy declared war on the United Kingdom on June 10th, 1940. Bordering on the Italian colony of Libya was the Kingdom of Egypt. Although a neutral country, Egypt was occupied by the British under the terms of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, which allowed British military forces to occupy Egypt if the Suez Canal was threatened. A series of cross-border raids and skirmishes began on the frontier between Libya and Egypt. On September 13th, 1940, an Italian force advanced across the frontier into Egypt, reaching Sidi Barrani on September 16th, where the advance was halted until logistical difficulties could be overcome. Italy's position in the centre of the Mediterranean made it unacceptably hazardous to send ships from Britain to Egypt via that route, so British reinforcements and supplies for the area had to travel around the Cape of Good Hope. For this reason, it was more convenient to reinforce General Sir Archibald Wavell's Middle East Command with troops from Australia, New Zealand and India. Nonetheless, even when Britain was threatened with invasion after the Battle of France. On December 9th, 1940 the Western Desert Force under the command of Major General Richard O'Connor attacked the Italian position at Sidi Barrani. The position was captured, 38,000 Italian soldiers were taken prisoner, and the remainder of the Italian force was driven back. The Western Desert Force pursued the Italians into Libya, and the 7th Armoured Division established itself to the west of Bardia, cutting off land communications between the strong Italian garrison there and Tobruk. On December 11th, Wavell decided to withdraw the 4th Indian Division and send it to the Sudan to participate in the East African Campaign. The 6th Australian Division (Major General Iven Mackay) was brought forward from Egypt to replace it and Mackay assumed command of the area on December 21st,1940.

After the disaster at Sidi Barrani and the withdrawal from Egypt, XXIII Corps (Generale di Corpo d'Armata (Lieutenant General) Annibale Bergonzoli) faced the British from within the strong defences of Bardia. Mussolini wrote to Bergonzoli, "I have given you a difficult task but one suited to your courage and experience as an old and intrepid soldier—the task of defending the fortress of Bardia to the last. I am certain that 'Electric Beard' and his brave soldiers will stand at whatever cost, faithful to the last." Bergonzoli replied: "I am aware of the honour and I have today repeated to my troops your message — simple and unequivocal. In Bardia we are and here we stay." Bergonzoli had approximately 45,000 defenders under his command. The Italian divisions defending the perimeter of Bardia included remnants of four divisions. Bergonzoli also had the remnants of the disbanded 64th "Catanzaro" Infantry Division, some 6,000 Frontier Guard (GaF) troops, three companies of Bersaglieri, part of the dismounted Vittorio Emanuele cavalry regiment and a machine gun company. These divisions guarded an 18-mile (29 km) perimeter which had an almost continuous antitank ditch, extensive barbed wire fence and a double row of strong points. The strong points were situated approximately 800-yard (730 m) apart. Each had its own antitank ditch, concealed by thin boards. They were each armed with one or two Cannone da 47/32 M35 (47 mm antitank guns) and two to four machine guns. The weapons were fired from concrete sided pits connected by trenches to a deep underground concrete bunker which offered protection from artillery fire.

Each post was occupied by a platoon or company. The inner row of posts were similar, except that they lacked the antitank ditches. The posts were numbered sequentially from south to north, with the outer posts bearing odd numbers and the inner ones even numbers. The actual numbers were known to the Australians from the markings on maps captured at Sidi Barrani and were also displayed on the posts themselves. The major tactical defect of this defensive system was that if the enemy broke through, the posts could be picked off individually from the front or rear. The defence was supported by a strong artillery component, yet the large number of gun models, many of them quite old, created difficulties with the supply of spare parts. The older guns often had worn barrels, which caused problems with accuracy. Ammunition stocks were similarly old and perhaps as many as two-thirds of the fuses were out of date, resulting in excessive numbers of dud rounds. Shortages of raw materials, coupled with the increased technological sophistication of modern weapons, led to production problems that frustrated efforts to supply the Italian Army with the best available equipment. As a "mobile reserve" there were thirteen M13/40 medium tanks and a hundred and fifteen L3/35 tankettes. The L3s were generally worthless, the M13/40s were effective medium tanks with four machine guns and a turret-mounted 47 mm antitank gun for its main armament that were "in many ways the equal of British armoured fighting vehicles". Bergonzoli knew that if Bardia and Tobruk held out, a British advance further into Libya eventually must falter under the logistical difficulties of maintaining a desert force using an extended overland supply line. Not knowing how long he had to hold out, Bergonzoli was forced to ration his stocks of food and water so that O'Connor could not simply starve him out. Hunger and thirst adversely affected the morale of the Italian defenders that had already been shaken by the defeat at Sidi Barrani.

On the Allied side, the 6th Australian Division had been formed in September 1939 as part of the Second Australian Imperial Force. Prime Minister Robert Menzies ordered that all commands in the division were to go to reservists rather than to regular officers, who had been publicly critical of the defence policies of right wing politicians. The result was that when war came, the Army's equipment was of World War I vintage and its factories were only capable of producing small arms. Fortunately, these World War I-era small arms, the Lee–Enfield rifle and the Vickers machine gun, were solid and reliable weapons that would remain in service throughout the war; they were augmented by the more recent Bren light machine gun. Most other equipment was obsolescent and would have to be replaced but new factories were required to produce the latest items, such as 3-inch mortars, 25-pounder field guns and motor vehicles; War Cabinet approval for their construction was slow in coming. The training of the 6th Australian Division in Palestine, while "vigorous and realistic", was therefore hampered by shortages of equipment. These shortages were gradually remedied by deliveries from British sources. Similarly, No. 3 Squadron RAAF had to be sent to the Middle East without aircraft or equipment and supplied by the Royal Air Force, at the expense of its own squadrons. Despite the rivalry between regular and reserve officers, the 6th Australian Division staff was an effective organisation. Brigadier John Harding, the chief of staff of XIII Corps, as the Western Desert Force was renamed on January 1st, 1941. Harding later considered the 6th Australian Division staff "as good as any that I came across in that war, and highly efficient." As it moved into position around Bardia in December 1940, the 6th Australian Division was still experiencing shortages. It had only two of its three artillery regiments and only the 2/1st Field Regiment was equipped with the new 25-pounders, which it had received only that month. Only A Squadron of the 2/6th Cavalry Regiment was on hand, as the rest of the regiment was deployed in the defence of the frontier posts at Al-Jaghbub and Siwa Oasis. The 2/1st Antitank Regiment had likewise been diverted, so each infantry brigade had formed an antitank company but only eleven 2-pounders were available instead of the 27 required. The infantry battalions were particularly short of mortars and ammunition for the Boys anti-tank rifle was in short supply.

To make up for this, O'Connor augmented Brigadier Edmund Herring's 6th Australian Division Artillery with part of the XIII Corps artillery: the 104th (Essex Yeomanry) Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery, equipped with sixteen 25 pounders. Italian gun positions were located using sound ranging by the 6th Survey Regiment, Royal Artillery. At a meeting with Mackay on Christmas Eve, 1940, O'Connor visited Mackay at divisional headquarters and directed him to prepare an attack on Bardia. O'Connor recommended that this be built around the 23 Matilda tanks of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel R. M. Jerrram) that remained in working order. The attack was to be made with only two brigades, leaving the third for a subsequent advance on Tobruk. Mackay did not share O'Connor's optimism about the prospect of an easy victory and proceeded on the assumption that Bardia would be resolutely held, requiring a well-planned attack. The plan developed by Mackay and his chief of staff, Colonel Frank Berryman, involved an attack on the western side of the Bardia defences by 16th Australian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Arthur "Tubby" Allen) at the junction of the Gerfah and Ponticelli sectors. Attacking at the junction of two sectors would confuse the defence. The defences here were weaker than in the Mereiga sector, the ground was favourable for employment of the Matilda tanks and good observation for the artillery was possible. Most of the artillery, grouped as the "Frew Group" under British Lieutenant Colonel J. H. Frowen, would support the 16th Australian Infantry Brigade; the 17th would be supported by the 2/2nd Field Regiment. Much depended on the Western Desert Force moving fuel, water and supplies forward. The 6th Australian Division Assistant Adjutant General and Quartermaster General (AA&QMG), Colonel George Alan Vasey said "This is a Q war".

A series of air raids were mounted against Bardia in December, in the hope of persuading the garrison to withdraw. Once it became clear that the Italians intended to stand and fight, bombing priorities shifted to the Italian airbases around Tobruk, Derna and Benina. Air raids on Bardia resumed in the lead-up to the ground assault, with 100 bombing sorties flown against Bardia between December 31st, 1940 and January 2nd, 1941, climaxing with a particularly heavy raid by Vickers Wellington bombers of No. 70 Squadron RAF and Bristol Bombay bombers of No. 216 Squadron RAF on the night of January 3rd, 1941. A naval bombardment was carried out on the morning of the 3rd by the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships HMS Warspite, Valiant and Barham and their destroyer escorts. The aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious provided aircraft for spotting and fighter cover. They withdrew after firing 244 15-inch (380 mm), 270 6-inch (150 mm) and 240 4.5-inch (110 mm) shells. The assault troops rose early on January 3rd, 1941. The leading companies began moving to the start line at 0416. The artillery opened fire at 0530. On crossing the start line the 2/1st Infantry Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Eather, came under Italian mortar and artillery fire. The lead platoons advanced accompanied by sappers of the 2/1st Field Company carrying Bangalore torpedoes—12-foot (3.7 m) pipes packed with ammonal—as Italian artillery fire began to land, mainly behind them. An Italian shell exploded among a leading platoon and detonated a Bangalore torpedo, resulting in four killed and nine wounded. The torpedoes were slid under the barbed wire at 60-yard (55 m) intervals. A whistle was blown as a signal to detonate the torpedoes but could not be heard over the din of the barrage. Eather became anxious and ordered the engineering party nearest him to detonate their torpedo. This the other teams heard, and they followed suit. The infantry scrambled to their feet and rushed forward, they advanced on a series of posts held by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Italian 115th Infantry Regiment. Posts 49 and 47 were rapidly overrun, as was Post 46 in the second line beyond. Within half an hour Post 48 had also fallen and another company had taken Posts 45 and 44. The two remaining companies now advanced beyond these positions towards a low stone wall as artillery fire began to fall along the broken wire.

The Italians fought from behind the wall until the Australians were inside it, attacking with hand grenades and bayonets. The two companies succeeded in taking 400 prisoners. The 2/2nd Infantry Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel F. O. Chilton) found that it was best to keep skirmishing forward throughout this advance, because going to ground for any length of time meant sitting in the middle of the enemy artillery concentrations that inflicted further casualties. The Australian troops made good progress, six tank crossings were readied and mines between them and the wire had been detected. Five minutes later, the 23 Matildas of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment advanced, accompanied by the 2/2nd Infantry Battalion. Passing through the gaps, they swung right along the double line of posts. The Italian defenders were cleared with grenades. By 0920 all companies were on their objectives and they had linked with 2/1st Infantry Battalion. However, several Bren gun carriers encountered problems as they moved forward during the initial attack. One was hit and destroyed in the advance and another along the Wadi Ghereidia. The 2/3rd Infantry Battalion was now assailed by half a dozen Italian M13/40 tanks who freed a group of 500 Italian prisoners. The tanks continued to rumble to the south while the British crews of the Matildas "enjoying a brew, dismissed reports of them as an Antipodean exaggeration". Finally, they were engaged by an antitank platoon of three 2 pounders mounted on portees. By midday, 6,000 Italian prisoners had already reached the provosts at the collection point near Post 45, escorted by increasingly fewer guards whom the rifle companies could afford to detach. The Italian perimeter had been breached and the attempt to halt the Australian assault at the outer defences had failed. Major H. Wrigley's 2/5th Infantry Battalion of Brigadier Stanley Savige's 17th Infantry Brigade, reinforced by two companies of Lieutenant Colonel T. G. Walker's 2/7th Infantry Battalion, now took over the advance. The battalion's task was to clear "The Triangle", a map feature created by the intersection of three tracks north of Post 16. Wrigley's force had a long and exhausting approach, and much of its movement forward to its jump off point had been under Italian shellfire intended for the 16th Infantry Brigade. Awaiting its turn to move, the force sought shelter in Wadi Scemmas and its tributaries. Wrigley called a final coordinating conference for 1030, but at 1020 he was wounded by a bullet and his second in command, Major G. E. Sell took over.

The artillery barrage came down at 1125, and five minutes later the advance began. The sun had now risen, and Captain C. H. Smith's D Company came under effective fire from machine guns and field artillery 700 yards (640 m) to the north east. Within minutes, all but one of the company's officers and all its senior non-commissioned officers had been killed or wounded. Meanwhile, Captain D. I. A. Green's B Company of the 2/7th Infantry Battalion had captured Posts 26, 27 and 24. After Post 24 had been taken, two Matildas arrived and helped to take Post 22. As the prisoners were rounded up, one shot Green dead, then threw down his rifle and climbed out of the pit smiling broadly. He was immediately thrown back and a Bren gun emptied into him. Upon hearing of the losses to the 2/5th Infantry Battalion, Brigade Major G. H. Brock sent Captain J. R. Savige's A Company of the 2/7th Infantry Battalion to take "The Triangle". Savige gathered his platoons and, with fire support from machine guns, attacked the objective, 3,000 yards (2,700 m) away. The company captured eight field guns, many machine-guns and nearly 200 prisoners on the way, but casualties and the need to detach soldiers as prisoner escorts left him with only 45 men at the end of the day. That evening, Brigadier Savige came forward to the 2/5th Infantry Battalion's position to determine the situation, which he accurately evaluated as "extremely confused; the attack was stagnant." Meanwhile, Captain G. H. Halliday's D Company moved southwards against Post 19. He drew the defenders' attention with a demonstration by one platoon in front of the post while the rest of the company moved around the post and attacked silently from the rear. This maneuver took the defenders by surprise and D Company captured the post—and 73 prisoners—at 0230. Although the Australian progress had been slower than that achieved during the break-in phase, the 17th Infantry Brigade had achieved remarkable results. Another ten posts, representing 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) of perimeter had been captured, the Switch Line had been breached, and thousands of Italian defenders had been captured. For the Italians, halting the Australian advance would be an immensely difficult task.

On the afternoon of January 3rd, Berryman met with Allen, Jerram and Frowen at Allen's headquarters at Post 40 to discuss plans for the next day. It was agreed that Allen would advance on Bardia and cut the fortress in two, supported by Frowen's guns, every available tank, MacArthur-Onslow's Bren gun carriers and the 2/8th Infantry Battalion, which Mackay had recently allocated from reserve. That evening, Berryman came to the conclusion that unless the Italian defence collapsed soon, the 16th and 17th Infantry Brigades would become incapable of further effort and Brigadier Horace Robertson's 19th Infantry Brigade would be required. The 2/1st Infantry Battalion began its advance on schedule at 0900, but the lead platoon came under heavy machine gun fire from Post 54, and Italian artillery knocked out the supporting mortars. The 3rd Regiment Royal Horse Artillery engaged the Italian guns and the platoon withdrew. The Italian guns were silenced when an Australian shell detonated a nearby ammunition dump. The Australians then captured the post. About a third of its defenders had been killed in the fighting. The remaining 66 surrendered. This prompted a general collapse of the Italian position in the north. Posts 56 and 61 surrendered without a fight and white flags were raised over Posts 58, 60, 63 and 65, and the gun positions near Post 58. By nightfall, Eather's men had advanced as far as Post 69 and only the fourteen northernmost posts still held out in the Gerfan sector. The advance resumed, only to come under machine gun and artillery fire from Wadi el Gerfan. The brigade major, Major I. R. Campbell, ordered MacArthur-Onslow, whose carriers were screening England's advance, to seize Hebs el Harram, the high ground overlooking the road to the township of Bardia. By the end of the second day, tens of thousands of defenders had been killed or captured. The remaining garrisons in the Gerfan and Ponticelli sectors were completely isolated. The logistical and administrative units were being overrun. Recognising that the situation was hopeless, General Bergonzoli and his staff had departed on foot for Tobruk during the afternoon, in a party of about 120 men.

On the morning of January 5th, the 19th Infantry Brigade launched its attack on the Meriega sector, starting from the Bardia road and following a creeping barrage southward with the support of six Matilda tanks, all that remained in working order. The others had been hit by shells, immobilised by mines, or had simply broken down. The company commanders of the lead battalion, the 2/11th Infantry Battalion, did not receive their final orders until 45 minutes before start time, at which point the start line was 3 miles (4.8 km) away. As they advanced, they came under fire from the left, the right, and in front of them, but casualties were light. Most positions surrendered when the infantry and tanks came close, but this did not reduce the fire from posts further away. Meanwhile, the Italian garrisons in the north were surrendering to the 16th Infantry Brigade and the Support Group of the 7th Armoured Division outside the fortress; the 2/8th Infantry Battalion had taken the area above Wadi Meriega; and the 2/7th Infantry Battalion had captured Posts 10, 12 and 15. The only post still holding out was now Post 11. The 2/6th Infantry Battalion renewed its attack, with the infantry attacking from the front and its carriers attacking from the rear. They were joined by Matildas from the vicinity of Post 6. At this point the Italian post commander, who had been wounded in the battle, lowered his flag and raised a white one. Some 350 Italian soldiers surrendered at Post 11. Godfrey sought out the Italian post commander—who wore a British Military Cross earned in the First World War—and shook his hand. "On a battlefield where Italian troops won little honour", Gavin Long later wrote, "the last to give in belonged to a garrison whose resolute fight would have done credit to any army."

The victory at Bardia enabled the Allied forces to continue their advance into Libya and capture almost all of Cyrenaica. As the first battle of the war to be commanded by an Australian general, planned by an Australian staff and fought by Australian troops, Bardia was of great interest to the Australian public; congratulatory messages poured in and AIF recruitment surged. In the United States, newspapers praised the 6th Division. An estimated 36,000 Italian soldiers were captured at Bardia, 1,703 (including 44 officers) were killed and 3,740 (including 138 officers) were wounded A few thousand (including General Bergonzoli and three of his division commanders) escaped to Tobruk on foot or in boats. The Allies captured 26 coastal defence guns, 7 medium guns, 216 field guns, 146 anti-tank guns, 12 medium tanks, 115 L3s, and 708 vehicles. Australian losses totalled 130 dead and 326 wounded. Bardia did not become an important port as supply by sea continued to run through Sollum but became an important source of water, after the repair of the large pumping station that the Italians had installed to serve the township and Fort Capuzzo. Axis forces reoccupied the town in April 1941, during Operation Sonnenblume, Rommel's first offensive in Cyrenaica. Bardia changed hands again in June 1942, being occupied by Axis forces for a third time and was re-taken for the last time in November unopposed, following the Allied victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#long post#british history#italy in ww2#italian history#north africa#australian history

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

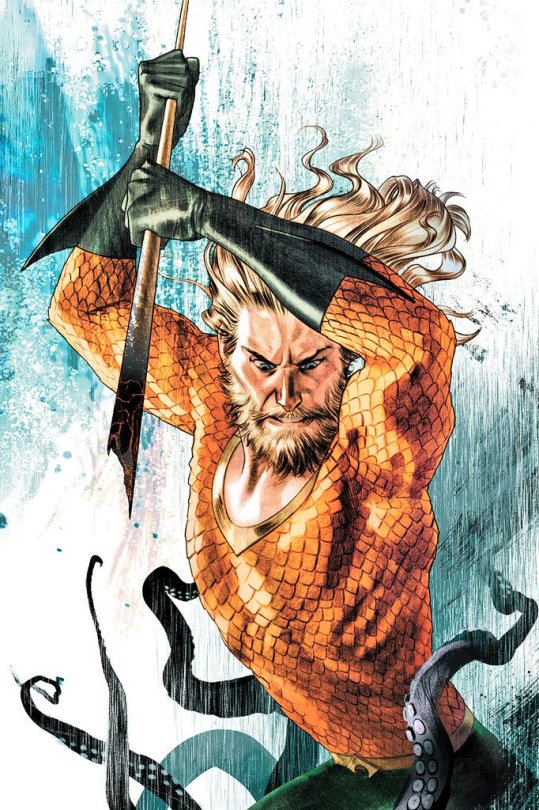

#0006 - Aquaman (Arthur Curry/Orin)

Age: 43

Occupation: King of Atlantis

Marital status: Married

Known relatives: Atlanna (mother), Tom Curry (stepfather), Atlan (father), Orm Marius (half-brother), Mera (wife), Arthur Curry Jr. (son, deceased), Koryak (son, deceased), Mareena Curry (daughter).

Group affiliation: Atlantis, formerly Justice League of America, Others

Base of operations: Poseidonis, Atlantis

Height: 6’1”

Weight: 325 lbs.

History:

43 years ago: Orin is born to Atlanna, queen of Atlantis. An ancient Atlantean superstition stated that children born with blond hair are cursed, and Atlanna and baby Orin are cast out from the kingdom. Atlanna travels to Amnesty Bay, Maine, where she meets lighthouse keeper Tom Curry. The two fall in love, and together they raise the child, newly rechristened Arthur.

33 years ago: Atlanna dies of pneumonia, due to a weakened immune system not accustomed to surface illnesses. On her deathbed, she tells Arthur of his true nature.

27 years ago: Tom Curry dies of a heart attack. After his funeral, Arthur leaves home to seek out his heritage.

26 years ago: Arthur briefly spends time in Alaska, falling in love with an Inuit woman named Kako and, unbeknownst to him, getting her pregnant. He’s driven away by the demonic god Nuliajuk before he can learn of the pregnancy.

24 years ago: Arthur is led to Atlantis by a pod of dolphins, and there he meets royal advisor Vulko and claims his birthright, learning of his heritage and usurping the crown from the corrupt king Orvax.

22 years ago: Orin first comes into conflict with Orm Marius, his half-brother, the Ocean Master, who tries to usurp the throne of Atlantis for himself.

20 years ago: Orin teams up with Barry Allen to fight the Trickster, and Barry dubs him “Aquaman.”

19 years ago:

Aquaman becomes a charter member of the Justice League after helping Earth’s heroes repel an alien invasion.

Orin meets Mera, queen of the exiled Atlantean city of Xebel, and the two marry soon thereafter.

Orin first encounters the undersea terrorist Black Manta.

18 years ago: Orin takes the young Atlantean mage Garth on as a protege.

17 years ago: Orin and Mera have their first child, Arthur Jr.

15 years ago: Arthur Jr. is murdered by the Black Manta as part of an elaborate scheme to take revenge on Aquaman and Atlantis for past defeats.

12 years ago: In the wake of the Justice League’s disbanding, Orin joins the Martian Manhunter’s new League, headquartered out of the Secret Sanctuary in Happy Harbor. Mera leaves him soon thereafter, wrecked with concerns over his commitment to her.

11 years ago: Aquaman is one of the many heroes involved in the fight against the Anti-Monitor.

10 years ago:

Aquaman again fights Ocean Master when the latter attacks Amnesty Bay.

Orin returns to Atlantis to find it conquered by a race of giant jellyfish. He succeeds in driving them out, and reclaims his throne.

9 years ago: Atlantis becomes embroiled in civil war, as Poseidonis is besieged and overrun by forces from Tritonis, allied with Black Manta

8 years ago:

Orin receives the Atlantis Chronicles, learning of his relation to Ocean Master and beginning to sink into a deep depression.

Orin and his ally Dolphin are kidnapped by the terrorist Charybdis, who plunges his arm into a pool of piranhas, cutting his left hand off at the wrist. He replaces it with a harpoon.

Arthur returns to the Arctic, meeting again with Kako and his fully grown son, Koryak. Koryak chooses to travel with him and Dolphin on their travels.

Orin joins the newly reformed Justice League of America in response to a White Martian threat on Earth.

Orin and Garth reunite after time apart, and Garth takes the new title of Tempest.

7 years ago:

Orin reunites the scattered city-states of Atlantis to stand together against the threat of Tiamat.

Orin’s harpoon hand is broken, and he is given a robotic hand to replace it, indistinguishable from flesh and blood.

Arthur and Mera reconcile as Atlantis goes to war with the island nation of Cerdia.

6 years ago:

Atlantis vanishes in the wake of the war against Imperiex, hurled into the Obsidian Age by Atlantean magic and enslaved by the sorceress Gamemnae. The Justice League and Orin succeed in returning Atlantis to its proper time.

A large portion of San Diego, California is sunken into the Pacific due to the machinations of Dr. Anton Geist. Orin annexes the city into Atlantis, taking San Diego native Lorena Marquez on as the new Aquagirl.

5 years ago: Atlantis is besieged by Lex Luthor’s Secret Society, and Aquaman leads the charge to defend it. Koryak dies during the battle.

4 years ago:

Arthur re-joins the Justice League.

Atlantis joins the United Nations, appointing Garth as their ambassador to the world.

3 years ago:

Orin comes into conflict with the Trench, a lost tribe of Atlanteans evolved to live in the deepest parts of the ocean.

Orin recruits a group of individuals into a team called the Others to search for lost Atlantean artifacts across the globe.

Half-Atlantean mage Kaldur’ahm comes to stand alongside Orin as the new Aqualad.

2 years ago: While Orin is on a mission with the Justice League, Orm seizes the throne of Atlantis for himself. Orin takes it back, and then decides to retire from superhero work to better rule his kingdom. Lorena Marquez becomes Aquawoman in his stead.

1 year ago: Arthur and Mera have their second child, a daughter named Mareena.

Present day: Orin and Mera begin to investigate the disappearance of the sea god Poseidon.

Commentary:

Aquaman is an interesting one, as for a long time he was a bit of a wildcard character, having many portrayals across various runs that differed wildly from one another, many of them a direct reaction to his depiction in Super Friends, which earned him a fair bit of public ridicule. What resulted was a regular cycle of Arthur being king of Atlantis and then being exiled, and he and Mera being together and then separated. This depiction aims to streamline that, with only one major period of exile from the throne, leading into the events of Peter David’s run, which are largely preserved here.

The lack of major Aquaman storylines in the twilight years of the post-Crisis DCU also allowed me to bring in several New 52 stories here, as well as introducing the idea from Young Justice of Arthur retiring from superhero work and passing his mantle on, again tying into the major theme of legacy that I’ve chosen to embrace. (Although, as Kaldur’ahm isn’t yet old enough in this timeline, that responsibility instead goes to Lorena Marquez.)

Arthur as a character is defined here by his responsibility, to his kingdom and to his family. He will defend them to the death and prioritize them before anything else, even if it causes him personal tragedy. Despite their past difficulties, he and Mera have reconciled and have a stable, loving relationship, and Arthur works hard to ensure that the disparate city-states that make up the loose nation of Atlantis remain at peace, even forsaking his duties with the Justice League to focus on his kingdom.

As far as physical appearance is concerned, the recent, Jason Momoa-inspired look DC’s been using as of late is absolutely perfect. It preserves the classic orange and green while giving him a little bit of an edge with the long hair and beard - a nice middle ground between the classic clean-cut Aquaman and the hook-handed Orin from David’s run. He’s a warrior king, he should look the part, and it’s almost a rule that every male superhero looks better with a beard.

Coming up next: Aquawoman (Lorena Marquez) and one that will sure to piss people off: Nightwing!

Got any questions? Asks are open!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

You knew Arthur was different. You knew he was smart. You knew more about him than even he knew. Vulko had sent his own daughter to befriend Arthur when he turned 16. As you and Arthur grew up together you began to sound more time being out doing something physical. Whether working out or swimming oceans you and Arthur were always together. As the two of you grew older he became bigger, stronger, his hair grew longer and hung over his shoulders now. His boyish roundness had dissolved to reveal the chiseled features that now stood before you. You weren't particularly sure when his boyish round face had disappeared, but now it was strong and held a nice soft beard. His soft skin now was covered in ink to show his roots, his arms once blank canvases now covered in artwork. His teeth shirts became a leather vest from your father and a tee shirt with the sleeves cut off.

You were both turning 26 years young today, and Arthur had taken you to the bar to drink to it. You two were best friends, after almost ten years you two were as close as you could get. He was there for you and you for him. He was strong and chiseled, you were strong but held a petite cuteness about you.

"I got a question Hun." He whispers, sliding his beer away from him and grabbing your hands. "We've been best friends and almost the same abilities, I don't know what I'd do without you. I know you get scared, but honey, I wanna be more than that. Closer than that. I want you to marry me."

"Arthur Curry! It took you long enough! But Art, we've never dated." You inquire.

"We've been dating longer than we knew. That's why we live together. That's why we've built this life together. We've been dating since we were young. Now I just get to kiss you. When you're awake." He mutters the last part and catches your attention.

"ARTHUR CURRY!" You shriek, busting into laughter and hugging his neck.

"It was a joke my dear. Now answer my question." He rumbles softly in your ear.

"Yes! Arthur I love you. You're my very own anti-hero! Arthur Curry, I love you so much. You are my king both on Earth and in the sea." You whisper, hugging him tighter. He hands you box with a tiny little starfish puffy sticker on top.

When you pop open the box, there's a little wave and quarter sized oval shaped aquamarine gem in the middle, held in by a couple waves. And on the top of the box where the little light it was an angler fish. You laugh hysterically at the fish before Arthur pulls the ring from it's safe harbor and slides it onto your finger, kissing your knuckles.

"Wait til Vulko hears about this." He chuckles, pressing a hard kiss to your forehead.

#jason momoa#jason momoa imagine#imagine#jasonmomoa#cute imagine#momoa#what have i done#lord jesus hes too cute#lord l love him#sweet lord#hes too precious#arthur#arthur curry#arthur curry imagine#arthurcurry#arthurcurryimagine#sorry not sorry#babyarthurcurry#baby Arthur Curry#teen arthur curry to adult arthur#teen arthur curry#cant wait to tell vulko

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay tumblr won’t let me format the ask properly so I’m reposting it. So a prompt from @allegoriesinmediasres : Ot3verse multimedia: bad “hot takes” about this timeline’s Tudor era, the OT3/Queen Mihrimah/Other nobles/etc. and people taking them apart.

CN: Biphobia, Homophobia, Anti-Semitism, Racism. Also the awesome responses are inspired by my friends @star-anise and @findingfeather

If I see one more person say that my TEXTUALLY BISEXUAL aren’t bisexual I am actually going to explode into a gay super villain who drops themed glitter on my enemies.

#they are BISEXUAL even if they didn’t have the word bisexual #ffs #like h8 being like ‘i love my wife and i love my husbands’ and the duke being like ‘i love the king and the queen’ and the queen being like ‘i love my husbands and also here is some evidence of romantic feelings for ladies as well’ #they are all like I LOVE BOTH OF THEM

(tudortrio)

Just because you want to make everything about you doesn’t mean it is. They were gay, like shut up karen just because you want to make everything comp het and bullshit it doesn’t mean it was. They were each others beards like, get over yourself and stop thinking you are entitled to representation from real people.

#i fucking hate the way people want to be special

(onlyoneandonly)

Okay firstly I’ve tagged this because there are so many biphobic slurs in this comment that I do not want people to have to deal with and secondly I’m a lesbian. Get In The Sea. Thirdly can I just say that the fact that the poster above is a pretty serious anti-semite on top of everything else is Super Fucking Great. I haven’t got the spoons right now to deal with this so I’m passing this on - @ani-sadia and @snowyswansofcastallen if you are up to it?

#disk course #one day since our last bullshit #tw: biphobic #tudortriadthings

(tudortrio)

I want to ask the people who are So Invested In Making These Three Into Something They Explicitly Did Not Want To Be Cast As how you’d feel if future historians did that to you - if they insisted that the people you explicitly said you love, you cherish, you desire and you have built a life with didn’t exist, that you Were Clearly Something Else despite the evidence. Because that’s what you are doing here.

None of these three were straight (read Queen Anne’s poetry and letters to Princess Renee and you can’t not see a baby wlw with A Giant Crush) but they were bisexual and yes, that is true even if they did not have the word bisexual.

The love letters. The extremely explicit about all three of them and their love love letters (like Henry talking about ‘how I have missed the three of us in our bed in my absence for I long to kiss your pretty dukkeys and to see our Duke pleasuring you as I am inside him’ is Pretty Damn Clear.

The Rings. The clear description of the marriage ceremony they undertook and Henry & Anne’s ‘We would crown you before the world, my love’ to Cromwell.

The ‘Shared A Bed Every Night’

The fact that Henry said ‘I have loved both men and women but truly, my heart and soul belongs only to you both my dark haired loves’

I would just like to hear why it’s so so terrible that these three were actually bisexual. They are not straight still.

(ani-sadia)

I hate the fact that we have to listen to this “duchess” talk about her supposedly special heritage like can’t you let us traditionalists have something when the royal family is diminished enough and then this bitch comes along and now we’ve got another one.

#i hate her #anti-catherine #yeah whatever we get it ur a jew and u are brown #fuck off #why can’t we just have something for once #i wish arthur tudor hadn’t died and then england could have been an empire #why can’t i be proud of being white anymore

(ladyofangland)

Oh. Oh. Royal fandom it’s been zero days since our last Fucked Up Nonsense. Usually I don’t respond to things like this because I Am Tired but I have so many anons in my inbox talking in this tone and I just…I AM DONE. It was the best thing that Thomas I and Mihrimah happened because it has made our world which is kind and fucks like the one above are genuinely a minority. They are still there and it’s still painful (as a non white person I just…it’s painful. I hate how they talk about how England Should Have Been An Empire And Also Why Did We Have To Not Do Imperialism It’s The Jews Fault is still a discourse) but yes, Catherine is allowed to talk about being biracial, about being jewish about being not straight.

I’m so glad she’s thriving and you are here, being A Fucking Sad Nonsense. Also Arthur Tudor is going to haunt your ass for the way you are speaking about his relatives just fyi.

(fixeachotherscrowns)

I don’t see what she said that was wrong - Catherine is really pushy about everything, like okay be whatever but you don’t have to go on about it all the time and make people feel bad about who they are. I’ve noticed Meghan does that too - they are both just really annoying and loud.

(delicatedarling)

Fuck Off. And Then Fuck Off Some More.

(duchessesofawesome)

#lil and her ridiculous aus#ot3: political power trio#fic#i should say in this universe the duchess of cambridge is a biracial bisexual jewish woman#also that yep england never did the imperialism/colonising thing because of it's biracial muslim queen and her husband who was raised#by his bisexual ot3 parents#self indulgent wish fullfillment by lil#jewish biracial fairy princess me

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Dead Redemption 2, a review

(Disclaimer: The following is a non-profit unprofessional blog post written by an unprofessional blog poster. All purported facts and statement are little more than the subjective, biased opinion of said blog poster. In other words, don’t take anything I say too seriously.

Just the facts 'Cause you're in a Hurry!

Publisher: Rockstar Studios

Developer: Rockstar Games

Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price (MSRP): 59.99 USD

How much I paid: 59.99 USD

Rated: M for Blood and Gore, Intense Violence, Nudity, Sexual Content, Strong Language and Use of Drugs and Alcohol.

How long I played: 50 Hours in an attempt to complete the story mode before Christmas rolls around