#Leo Catozzo

Photo

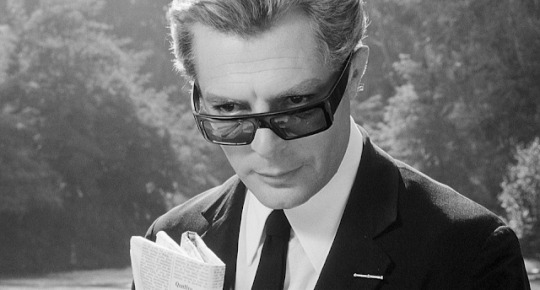

Marcello Mastroianni in 8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Casti: Marcello Mastroianni, Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimée, Sandra Milo, Rossella Falk, Barbara Steele, Madeleine Lebeau, Eddra Gale, Guido Alberti, Jean Rougeul. Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Brunello Rondi. Cinematography: Gianni Di Venanzo. Production design: Piero Gherardi. Film editing: Leo Catozzo. Music: Nino Rota.

At one point in 8 1/2 an actress playing a film critic turns to the camera and brays (in English), "He has nothing to say!", referring to Guido Anselmi, the director Marcello Mastroianni plays, and by extension to Fellini himself. And that's quite true: Fellini has nothing to say because reducing 8 1/2 to a message would miss the film's point. Guido finds himself creatively blocked because he's trying to say something, except he doesn't know what it is. He has even enlisted a film critic (Jean Rougeul) to aid him in clarifying his ideas, but the critic only muddles things by his constant monologue about Guido's failure. Add to this the fact that after a breakdown Guido has retreated to a spa to try to relax and focus, only to be pursued there by a gaggle of producers and crew members and actors, not to mention his mistress and his wife. Guido's consciousness becomes a welter of dreams and memories and fantasies, overlapping with the quotidian demands of making a movie and tending to a failed marriage. He is also pursued by a vision of purity that he embodies in the actress Claudia Cardinale, but when they finally meet he realizes how impossible it is to integrate this vision with the mess of his life. Only at the end, when he abandons the project and confronts the fact that he really does have nothing to say, can he realize that the mess is the message, that his art has to be a way of establishing a pattern out of his own life, embodied by those who have populated it dancing in a circle to Nino Rota's music in the ruins of the colossal set of his abandoned movie. The first time I saw this film it was dubbed into German, which I could understand only if it was spoken slowly and patiently, which it wasn't. Even so, I had no trouble following the story (such as it is) because Fellini is primarily a visual artist. Besides, the movie starred Mastroianni, who would have made a great silent film star, communicating as he did with face and body as much as with voice. It is, I think, one of the great performances of a great career. 8 1/2 is also one of the most beautiful black-and-white movies ever made, thanks to the superb cinematography of Gianni Di Venanzo and the brilliant production design and costumes of Piero Gherardi.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le notti di Cabiria (Federico Fellini, 1957).

#le notti di cabiria (1957)#le notti di cabiria#nights of cabiria#nights of cabiria (1957)#federico fellini#giulietta masina#aldo tonti#leo catozzo#piero gherardi

194 notes

·

View notes

Photo

- I am ignorant, but I read books. You won't believe it, everything is useful... this pebble for instance.

- Which one?

- Anyone. It is useful.

- What for?

- For... I don't know. If I knew I'd be the Almighty, who knows all. When you are born and when you die... Who knows? I don't know for what this pebble is useful but it must be useful. For if its useless, everything is useless. So are the stars!

La strada, Federico Fellini (1954)

#Federico Fellini#Tullio Pinelli#Anthony Quinn#Giulietta Masina#Richard Basehart#Aldo Silvani#Marcella Rovere#Livia Venturini#Otello Martelli#Nino Rota#Leo Catozzo#1954

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

8½ (1963, Italy)

As a bored and depressed teenager and before I ever delved into classic movies, I looked online for lists of the best films ever made. Certain titles from more reputable websites kept appearing – one of those frequently-mentioned titles was Federico Fellini’s 8½. Soon after, I began actively seeking out these films. I was fifteen years old when I first encountered 8½, and I remember thinking to myself that there was something about Fellini’s film I could not quite grasp at the time. I stopped, barely a third into the movie, made no judgments, and did not finish it. Nine or ten years have passed (this was one of the first movies in my classic movie adventure so I know how old I was; I just don’t remember which year I saw it in), and upon this revisit to 8½ and completing the film, it is the greatest artwork about artist’s block I have ever seen. The film comments on the torment surrounding artistic creation, and how an individual’s personality – their ego, ability to examine themselves, and attitudes towards others – make that struggle unique to that artist. At times a bawdy comedy, 8½ – referring to the fact that Fellini had directed six feature-length films and three short films before this production, equaling 7½ – is also a dramatic surrealist fantasia filled with behavioral inconsistencies and fanciful sequences entangling dreams and reality.

And so by 1963, Federico Fellini, who gleamed off the Italian neorealist master Roberto Rossellini (1945′s Rome, Open City and 1948′s Germany Year Zero), and directed neorealist-inspired films in I Vitelloni (1953), La Strada (1954), and Nights of Cabiria (1957), was beginning to dip into the fantastical. These later fantastical films, however, were primarily steeped in modernity – demanding much from the audience, as Fellini uses impossible images to express ideas and states of mind that would become uncinematic if explained by dialogue.

In the midst of starting production on his next movie while resting at a Roman spa, acclaimed director Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is struggling over how to approach the autobiographical elements he is integrating into a science fiction piece. Late in pre-production, Guido is having tensions with (and not just limited to) his mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo); wife, Luisa (Anouk Aimée); and producer, Pace (Guido Alberti). His friends, Rossella (Rossella Falk) and Mario (Mario Pisu), are unsure how to help him, as he drifts day-to-day between his loud, bickering-heavy reality and his fantasies. Those fantasies are not always clearly indicated by 8½’s editing by Leo Catozzo – the movie begins with a suffocating traffic jam, progresses to images of Guido’s childhood in a seaside village, his Catholic school days where he was punished for dancing with a prostitute (Eddra Gale), and features a handful of sexual fantasies that include the film’s darkly uproarious harem scene involving all the women from Guido’s past and present life (the movie is suggestive, not explicit, with sex – the former always more difficult to film). Claudia Cardinale stars as Guido’s fantastical Ideal Woman and as Claudia, an actress who appears briefly, but notices something about Guido’s idea and his persona that pierces his psychological armor.

Fantasy and reality, in competition across 8½, are harmonious in the closing minutes. Whether or not the ending is a statement of Guido’s (and, by the fact this film is at least somewhat biographical, Fellini himself) impeccable artistry, comic relief, or both is perhaps the most vexing question I continue to wrestle with. At twenty-five years old, I find myself giving tentative answers to the film’s questions; this write-up might read much differently if written at a later stage in my life.

The screenplay by Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Brunello Rondi (Flaiano, Pinelli, and Rondi being frequent Fellini collaborators) models Guido as Fellini’s alter ego. Marcello Mastroianni, as Guido, inhabits the role with a physical fatigue similar to his role of Mario in Le Notti Bianche (1957). But if Mario was less tragic and more fashionable, he would be Guido. Mastroianni is excellent in displaying his character’s brokenness due to constant rumination over his noncommittal habits, inability to express his feelings, and his search for sexual gratification compounding his emotional and social emptiness. All of this will affect his artistry. The moment Guido walks outside his hotel room, he is besieged by the film’s crew and actors who have not even been officially cast. What do you want for this scene? When will we start shooting? I can’t wait to appear in your film! The barrage (those were paraphrases) lasts all morning until the moment late at night Guido slams his hotel door shut, readying himself to be with a woman he only seems to care for. His creative side is so exhausted that not even Mastroianni’s dialogue delivery changes tone when producer Pace fumes at the excessive production delays – no sarcasm, not even a nonplussed shoulder shrug. Mastroianni, debatably the greatest Italian actor of all time, exemplifies incredible discipline in this role.

With an unsustainable, ridiculous situation unfolding, 8½ partly becomes a tragicomedy – if the film weren’t so absurd and racy, it would be more difficult to watch. In this movie about an Italian, Felliniesque director unable to make a movie, Fellini has crafted a movie teeming with introspection and visual splendor. Guido’s sexuality seems inspired by Rubens’ portraits; his relations to everyone (but especially women – who, to him, are either maternal figures or harlots) predicated on what they can do for him. He might not fit the stereotype of the tyrannical director, but his self-worth has become defined by the most external: his professional accomplishments and his romantic conquests that seem to be without indications of abusive behavior. As the viewer intuits Guido’s character, his biographical flashbacks are understood as less reliable, more subjective. To what extent are those flashbacks colored, censored by nostalgia for a childhood or adolescence that Guido chooses to remember? There are no answers to that question in 8½. The film’s aforementioned introspection falls to the viewer. Guido, expending so much time thinking about his upcoming production, leads a life unexamined.

At this point in his life he arrives at what appears to be a spiritual dead end. That just so happens to contribute to his director’s block. Hearing from the others working on Guido’s film, we hear their concerns about the structure of the movie and nobody understanding what it is saying. To the crew, it is a jumbled patchwork of philosophical avant garde for the sake of being philosophical avant garde.

In outdoor scenes, cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo (1962′s L’Eclisse, 1965′s Juliet of the Spirits) has his camera motion side-to-side in the direction of character movements, suggesting restlessness. When characters are shown with a shallow foreground, one feels Guido’s anxiety considering the demands and hopes of others. In moments where there are fewer characters and when they are placed further away from the camera, the camera moves more dramatically, as if floating in air. It contributes to the dreamlike quality of several scenes – including Claudia Cardinale’s introduction in the movie – even when Guido has no space to fantasize. The production design and costume design by Piero Gherardi (La Dolce Vita and Juliet of the Spirits) showcases ‘60s elegance, with Rome’s rich mingling at the spa Guido is staying. Here, 1960s Italy clashes with what appears to be Ancient Roman and Renaissance-era architecture (free-to-read English-language literature on the film does not specify if these outdoor sets were constructed for 8½ or are actual attractions, but the film was shot entirely around Rome and the Lazio administrative region – where Rome is located). The aesthetic differences in architecture at the spa are reflections of the contradictory and unsettled statuses Guido’s imagination and soul.

So too is Nino Rota’s celebratory, yet mysterious and varied score. Like his work on La Strada, Rota has a main theme influenced by circus and carnival music. Where in La Strada (that film partly inspired by Fellini’s memories of circuses and clowns) that decision made literal sense because the characters are traveling circus performers. Here, it is to echo the madness of Guido not knowing what to do and being surrounded by a gaggle of irate businessmen, sycophantic actors looking for a job, and confused craftspersons having to alter their work due to their ineffectual director. For 8½ – a fragmented story where Guido’s bitter life is intercut with his daydreams – the score lacks stylistic cohesion. Interspersed with the circus and carnival music is Rota’s take on jazz, mid-century popular music, and brief quotations of classical music. In another film about a different subject, this Rota’s score would be bothersome. Because of the protagonist’s nature and unpredictable editing (at least, for first-time viewers), these frequent and rapid musical transitions fit the film.

youtube

Fellini also faced his own writer’s block while figuring out the screenplay to 8½. At some point during writing, Fellini resolved that the protagonist – originally a writer – would be changed to a movie director (read: Fellini himself). Bear with me on this one: everything that Guido says within the film about the film he is making can also be said about 8½. And yet 8½ never descends into self-conscious or self-referential meta humor taking the viewer out of one of the most rapturous pieces of cinema. That is because it paints a tapestry of individuals living among our troubled protagonist: rich and poor; vulgar and refined; conciliatory and uncompromising; vacuous and perceptive; and so forth. The film poses existential questions about how Guido’s self-perception is impacting how he treats others and his artistic abilities. And though you might not sympathize with Guido given his misadventures, you will wonder how similar you are to him. Reaching the answer, do you flinch at what you have found?

8½ dispenses with conventional cinematic form. Compared to films of the French New Wave – ongoing during 8½’s release and more intent on breaking norms – Fellini’s film, despite being inundated with autobiographical meta, achieves an intense thoughtfulness without ever taking itself too seriously. Fellini, himself in artistic transition, makes a stunning statement by obscuring the separation between his neorealist origins and reverie. The answers to Fellini’s questions, as well as Guido’s and ours, are found in both.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. 8½ is the one hundred and forty-seventh film I have rated a ten on imdb.

#8½#8 1/2#Federico Fellini#Marcello Mastroianni#Claudia Cardinale#Anouk Aimée#Sandra Milo#Rossella Falk#Barbara Steele#Jean Rougeul#Ennio Flaiano#Tullio Pinelli#Brunello Rondi#Gianni Di Venanzo#Leo Catozzo#Piero Gherardi#Nino Rota#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Boccaccio 70

Boccaccio 70 (1962) Italia

4 cortos dirigidos por 4 diferentes artistas

Director→ Mario Monicelli, Federico Fellini, Luchino Visconti, Vittorio De Sica

Foto→ Otello Martelli, Armando Nannuzzi, Giuseppe Rotunno

Música→ Nino Rota, Armando Trovaioli

Guion→ Giovanni Arpino, Suso Cecchi d'Amico, Italo Calvino, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Federico Fellini, Brunello Rondi, Goffredo Parise, Luchino Visconti, Cesare Zavattini

Edición → Leo Catozzo

Actores→ Germando Gilioli, Marisa Solinas, Peppino De Filipo, Sofia Loren

Notas:

- Re interpretación moderna del decameron

- mi corto favorito fue el que dirigió Vittorio da Sica

0 notes

Photo

Giulietta Masina and Anthony Quinn in La Strada (Federico Fellini, 1954)

Cast: Anthony Quinn, Giulietta Masina, Richard Basehart, Aldo Silvani, Marcella Rovere, Livia Venturini. Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano. Cinematography: Otello Martelli. Production design: Mario Ravasco. Film editing: Leo Catozzo. Music: Nino Rota.

Sad clowns have gone out of style, so to many of us today Giulietta Masina's Gelsomina seems more than a little cloying. But when La Strada was released, she was hailed as a master of comic pathos, as if she were the unacknowledged daughter of Charles Chaplin and Lillian Gish. Similarly, Federico Fellini's film now feels like an uneasy attempt to blend neorealistic grime and misery with a kind of moral allegory: Zampanó as Body, Gelsomina as Soul, and The Fool as Mind. So when Body kills Mind, Soul pines away, leaving Body in anguish. But La Strada has retained generations of admirers who are willing to overlook the sentimentality and latter-day mythologizing. It remains a tremendously accomplished film, made under some difficulties, including constant battles by Fellini with his formidable producers, Dino De Laurentiis and Carlo Ponti. If it sometimes feels like a throwback to the era of silent movies, it was virtually filmed as one, with its American stars, Anthony Quinn and Richard Basehart, speaking their lines in English and the rest of the cast speaking Italian, and everyone later dubbed in the studio -- which leads to that slightly disembodied quality the dialogue of many early postwar films possesses.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcello Mastroianni in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960)

Cast: Marcello Mastroianni, Anita Ekberg, Anouk Aimee, Yvonne Furneaux, Magali Noël, Alain Cuny, Annibale Ninchi, Walter Santesso, Valeria Ciangottini, Riccardo Garroni, Alain Dijon, Lex Barker, Jacques Sernas, Nadia Gray. Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Brunello Rondi. Cinematography: Otello Martelli. Production design: Piero Gherardi. Film editing: Leo Catozzo. Music: Nino Rota.

La Dolce Vita was among the celebrated international films that challenged Hollywood's hegemony in 1960, including René Clément's Purple Noon, Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura, Luchino Visconti's Rocco and His Brothers, and Yasujiro Ozu's Late Autumn. It established Federico Fellini as one of the world's most important filmmakers. I was very young when I first saw it, and it dazzled me with its nose-thumbing satire of a shallow, hedonistic culture. I remember being impressed particularly by the scene at the home of Steiner (Alain Cuny), the ill-fated intellectual whose life and ideas also made their mark on Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni), Fellini's protagonist, a journalist with ambitions to become a "serious" writer. What I missed at that time was that Steiner was as much a target of satire as the movie stars, aristocrats, and hucksters that swarm around Marcello's Rome. Steiner's soiree is as empty and sterile, as decadent in its own way as the scenes of boozing and party-hopping and religious mania. But at least there's an energy to those scenes that keeps the film alive. Even though Steiner's story is tragic, La Dolce Vita is a profoundly anti-intellectual movie. And of all the films I just named, despite its technical prowess, it seems to me the least impressive, the one most touched by the passage of time.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Le notti di Cabiria (Federico Fellini, 1957).

#le notti di cabiria#le notti di cabiria (1957)#federico fellini#giulietta masina#aldo tonti#leo catozzo#piero gherardi#the nights of cabiria (1957)#the nights of cabiria

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes