#Margaret and Edward's almost decade-long exile before it

Text

Henry VII & Elizabeth of York's Dynastic Union

“Henry VII did not remarry. It is difficult to know, at this distance, just how sincere his marital attempts were; whether they were driven by personal factors or simply another facet of the complicated game of European politics, or both. It would be misleadingly anachronistic to separate these motives and see his attempts at wooing as anything less than his royal duty. If he was looking for comfort, he might have found a willing wife closer to home, among his own nobility; dynastically, the pool of available women failed to provide him with a successful candidate. Perhaps it was the very geographical and political distance between him and these potential brides that made them attractive; the king was the ultimate prize in the delicate game of foreign alliances and to commit himself may have risked alienating other potential unions. He was spoilt for choice, so long as his marriage remained theoretical. There is no doubt about the genuine grief he exhibited at the loss of his wife, retreating ‘to a solitary place to pass his sorrow’ and seeing no one except ‘those appointed’. Ill health increasingly plagued him during the last years of his life, as he resigned himself to his losses.”

- IN BED WITH TUDORS: THE SEX LIVES OFA DYNASTY FROM ELIZABETH OF YORK TO ELIZABETH I by Amy Licence

“In many ways, the union had long been inevitable. From the early negotiations of Edward IV, bogus though they might have been, through the long years of plotting and maneuvering in separate exiles, emerging against all odds as the inheritors of their respective houses, Henry and Elizabeth moved steadily towards each other. Now that they were joined together, they would rarely be apart for the rest of their lives-unless necessity wedged between them.”

- ELIZABETH OF YORK by Nancy Lenz Harvey

"In theory, it was a perfect match. Henry claimed the throne by right of conquest and had overthrow a regime that had been unpopular in many places, tainted by the controversy of Richard’s accession and the disappearance of Edward V. His Lancastrian roots gave him the requisite degree of authority but he had not been heavily embroiled in the bloody events of recent decades, making him a new face on the political scene. However he was still sufficiently British, having been born at Pembroke Castle and spending many of his early years as a ward of the Herbert family in their impressive Raglan Castle home; there had been the possibility of a marriage to their daughter Maud before the events of 1485 unfolded. Elizabeth’s popularity was legendary. The common sympathy for her sufferings also assimilated much of the outrage and grief surrounding the deaths of her brothers and the majority of England recognized her as the rightful heir of the house of York. However, there was no expectation that she could rule alone. A woman’s subordinate position to her husband extended even to those through whom the inheritance traveled. She was of marriageable age, tall, beautiful and had been brought up in anticipation of queenship. The union had been proposed by their mothers through the long days of suffering under Richard, liaising in secret through the offices of a mutual doctor and astrologer while the dowager queen remained in sanctuary. The prospect of success must initially have seemed remote. Eventually, if Henry had married either daughter of the protectors of his youth, Anne of Brittany of Maud Herbert, Elizabeth would have even free to marry and take her royal inheritance elsewhere. Providing she chose carefully, she and her husband would then have been rival claimants to the English throne and perpetual thorns in Henry’s side. So, to what extent did Henry and Elizabeth choose each other? The union was practically decided by the time they eventually met, probably in early September 1485 … Henry’s splendid coronation took place on 30 October 1485 … The wedding did not take place, though, for another three months. This is not to suggest Henry was not keen for the match, as some historians have concluded: there was his first parliament to sit, repeals of the law to ensure that Elizabeth’s illegitimacy was rescinded and dispensations to secure, as well as a terrible outbreak of plague in the capital that autumn … Henry also want to ensure his kingship was established and independent of Elizabeth’s claim before the ceremony took place. The couple probably met on a number of occasions, both at court and at Margaret Beaufort’s home, Coldhabrbour House, an ancient building originally named La Tour, comprising two linked fortified town houses, with a number of chambers of suites of rooms within its tower and a Great Hall on the riverside. Perhaps Henry was taking the time to get to know his bride; more cynically, it has been suggested he was ensuring she was not carrying of his predecessor. Elizabeth was not pregnant But she may have finally yielded to Henry’s advances once the union appeared a certainty. The couple’s first child would arrive the following September, exactly eight months after the wedding, a time frame which has given rise to much subsequent historical speculation. Assuming the baby was full-term, conception must have occurred in mid-December 1485. Parliament approved the match on 10 December 1485, suggesting consummation around that time, almost exactly nine months before the birth.

Predictably, early Tudor chroniclers were full of blessings for the match. The fourth Croyland continuer wrote that the marriage, 'which from the first had been hoped for’, was lauded for the sake of Elizabeth’s title as well as her virtues: 'in whose person it appeared that every requisite might be supplied, which was wanting to make good of the title of king himself’. He cites a poem included by the previous Croyland writer that 'since God had now united them and made but one of these two factions, let us be content’. Other writers celebrated that 'harmony was thought to discend out of hevene into England’ from this 'long desired’ match. Shakespeare presents them as the 'true succeeders of each royal house, by God’s fair ordinance conjoin together’. Their heirs would bring 'smooth-faced peace, with smiling plenty and prosperous days’. Hall claimed the match 'rejoiced and comforted the hartes of the nobe and gentlemen of the realme’ and 'gained the favour and good minds of all the common people’ ...

Henry also sought to obtain a second papal dispensation for the match, as the pair were related within the fourth degree: he already had one dating to March 1484 and could not allow any possibility of the marriage being invalid. This involved religious and legal specialists giving depositions about their respective lineages before witnesses, which was confirmed by the current papal legate to England, James Bishop of Imola. He was successful on 16 January. Two days later, Elizabeth and Henry were married."

- ELIZABETH OF YORK: THE FORGOTTEN TUDOR QUEEN by Amy Licence

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

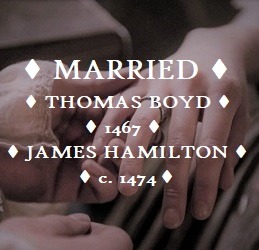

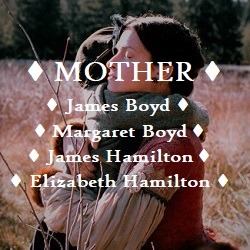

Shoddy History Edits: Mary Stewart, Countess of Arran

The oldest surviving daughter of James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders, Mary Stewart was probably born in Stirling in July 1451*. Over the course of the next decade she would be joined by at least five siblings, four of whom lived to adulthood- the future James III (b.1452), Alexander Duke of Albany, John Earl of Mar, and Lady Margaret Stewart. Although their births secured the future of the Stewart dynasty, the early lives of these children were not exactly stable and Mary would lose both her parents by the age of thirteen. Following her father’s accidental death at Roxburgh in 1460, her mother took charge of the government of Scotland on behalf of the young James III, until her own early demise in late 1463. After this Mary’s powerful kinsman James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews, assumed a leading role in the kingdom’s affairs but when he died in turn in 1465, things began to get a bit out of hand. Possession of the king’s person was a valuable commodity during Scottish minorities and it wasn’t long before the favoured tactic of ‘rule by kidnap’ was employed by Robert, Lord Boyd.

In summer 1466, a group of Boyd supporters led by Robert’s brother, Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll, seized the fourteen year old James III while the king was out hunting near Linlithgow, and took control of government. A reasonable amount of nest-feathering ensued, which was not entirely unexpected. However the Boyds seem to have overstepped the mark when, on or around 26th April 1467, Lord Boyd’s eldest son Thomas was created Earl of Arran and wed the king’s older sister Mary. We don’t know what Mary herself thought about this sudden development but her brother certainly didn’t like it- James would claim in later years that he wept at the wedding, but was unable to stop it out of fear that he and his brothers would be destroyed. This bold move from the Boyds- whose chief representative was only a lord of parliament before 1467- may not have impressed the wider political community much either, especially since Mary was the eldest daughter and was probably expected to make an important match with another powerful European dynasty*. After all, several of her paternal aunts had married into princely dynasties- like the late Margaret (d.1445), who had married the dauphin of France, Isabella (d. after 1494) who married the duke of Brittany, and Eleanor (d.1480) who married the (Arch)duke of Further Austria, while three other aunts had also been involved in important, if obviously less impressive, marriage negotiations. During her mother’s negotiations with Margaret of Anjou in 1460, Mary herself had been suggested as a bride for Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, the son of the exiled Henry VI of England. But as fate would have it, neither of James III’s sisters were destined to marry outside the kingdom- although, like her younger brother Alexander, Mary would experience her fair share of European travel.

After three years of power, the tide began to turn for the Boyds in the summer of 1469. Robert, Lord Boyd had been busy over the past year arranging the king’s marriage to Margaret, daughter of Christian I of Denmark, and now he and his son Thomas, Earl of Arran, had the honour of escorting the royal bride back to Scotland. But in the meantime James III had finally managed to seize the reins of government, and, by the by, he had also come to the conclusion that Lord Boyd and his son weren’t really in need of their heads. This must have put something of a damper on proceedings when the Boyds’ ship docked in Leith. Later sixteenth century accounts claim that Thomas Boyd was intercepted on board by his wife Mary, who warned him of her brother’s intentions. Instead of disembarking with the rest of the fleet, the couple promptly sailed away from Scotland again, with Thomas’ father Robert joining them later in exile- a sensible precaution really since James had Robert’s brother Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll executed on the castle hill of Edinburgh a few months later, and forfeited the possessions and lives of Robert and Thomas Boyd in absentia**. Whether or not Mary played an active role in the flight of her husband and father-in-law like the sixteenth century writers claim***, we do know that she joined them in exile. Sixteenth century sources claim that the Boyds in vain sought the support of the king of France, while contemporary sources show that Mary and the Boyds took refuge in Flanders, throwing themselves on the mercy of her cousin Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

Bruges was then a fashionable place for exiled British royals to mooch around (Edward IV of England and co. were also in residence over the winter of 1470-71). Charles the Bold was not always a reliable ally but, in the Boyds’ case, he did at least send a message to James III through his ambassador Anselm Adornes (soon to become a favourite with the king of Scots), asking for the Scottish exiles to be pardoned and allowed to return home. James thanked the duke for his courtesy to his sister but stoutly refused, recounting the Boyds’ crimes and arguing that the duke, “ought no longer to favour traitors, who to the king’s dishonour had brought his sister to exile in many foreign lands.” So the Scottish exiles remained in Bruges for some time, staying at the Hotel de Jerusalem which belonged to Anselm Adornes while its owner went on pilgrimage to the real Jerusalem. During this time Mary gave birth to two children- James and Margaret Boyd- whose godmother was Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy.

In late 1471, though, the situation looked like it was improving. Some modern historians interpret the sources as stating that a plan was developed for the Boyds and Mary cross the sea again, and for Mary to travel to Scotland to soften her brother up while the Boyds waited in England until it was safe for them to return. On the other hand, sixteenth century writers like George Buchanan and John Leslie were of the opinion that James III had lured his sister home under false pretences, “on account of the great love she bore to her husband.” In any case, a safe conduct from Calais was granted to the exiles, and to Anselm Adornes who was to accompany them, and they sailed for England in October 1471. Thomas Boyd said goodbye to the rest of the group in the southern kingdom, and went to the court of the newly restored Edward IV, where he had business with the king. The rest of the party went on to Alnwick, where they were to remain to await the outcome of Mary’s mission (Robert, Lord Boyd, now quite old, is supposed to have died there). Mary then crossed the border with Anselm Adornes and his wife. She is not known to have seen her first husband again.

Little is certainly known of Mary’s career between her return to Scotland in 1471-2 and her second marriage in 1474, but clearly any plans to restore the Boyds to favour failed. Mary herself was receiving ferms from lands in Scotland by late 1473 at least, if not earlier, indicating that, if not exactly back in favour, she was at least able to conduct some business without royal obstruction. Both Leslie and Buchanan (and other writers) claim that she was detained by her brother in Ayrshire while James III wrangled a divorce between Mary and Thomas. The grounds and exact process of any such “divorce” are unknown, other than Buchanan’s puzzling story that the king summoned Thomas Boyd to Kilmarnock to answer for his crimes within sixty days and that, when Boyd naturally failed to appear, the marriage was declared illegitimate. Mary was then married (by force and “against her inclination” according to Buchanan) to James, Lord Hamilton, a man many years her senior but greatly favoured by the king. Once again we do not know Mary’s thoughts on this match, but it had taken place by Easter 1474, when, at the king’s command, “my Lady of Hammiltoune the Kingis sister” was given six ells of purple velvet for a kirtle. We know this was not James III’s younger sister Margaret (though she did later reside in Hamilton) since in July of the same year, Lord Hamilton surrendered several lands into the king’s hands so that they could be granted back in conjunct fee to the couple, with the wife named as “Marie Senescalli ejus sponse, sorori regis”. But aside from the minor detail that Mary’s first husband was perhaps still cutting about, there were other impediments which made the new couple’s relationship less than legal. Accordingly, in April 1476, Pope Sixtus dispensed them from the impediments of consanguinity, affinity, and public honesty, and declared the child which had since been born to them legitimate. By the time of Lord Hamilton’s death three years later, at least two children had been born of the marriage- a boy named James and a girl named Elizabeth.

In the meantime, Mary’s first husband Thomas appears to have died abroad, though we have almost no information about his life following their separation, and even the sixteenth century writers do not agree on this point. Buchanan claims that he died in Antwerp not long after the “divorce”, and was buried there with great honour on the orders of Charles the Bold (he also gives his personal opinion that James Hamilton was far inferior to Mary’s first husband- hindsight is a wonderful thing). The Italian humanist Giovanni Ferreri had obviously heard very different stories about Thomas and his character from his Scottish sources, and, in his rather unreliable continuation of Hector Boece’s history, he gave Thomas a reputation as a man capable of any vice, and claimed that, after much travelling in Europe, he was murdered in Italy by a man whose wife he had seduced. But two letters in the celebrated collection of the Pastons of Norfolk have survived which refer to Thomas Boyd’s time in England , and the first of these gives a very different character sketch to that offered by Ferreri- and a rare contemporary insight into the whole affair. On 5th June 1472, John Paston the younger wrote to his older brother of the same name:

“"Also I prey yow to recomand me in my most humbyll wyse unto the good Lordshepe of the most corteys, gentylest, wysest, kyndest, most compenabyll, freest, largeest, most bowntesous knyght, my Lord the Erle of Arran, whych hathe maryed the Kyngs sustyr of Scotland. Herto he is one the lyghtest, delyverst, best spokyn, fayrest archer; devowghtest, most perfyghte, and trewest to hys lady of all the knyghtys that ever I was aqweynted with; so wold God, my Lady lyekyd me as well as I do hys person and most knyghtly condycyons, with whom I prey yow to be aqweynted, as yow semyth best; he is lodgyd at the George in Lombard Street.**** He hath a book of my syster Annys of the Sege of Thebes; when he hath doon with it, he promysyd to delyver it yow."

We are offered no such contemporary insight into Mary’s character, which must remain something of a mystery, although if even half of what the sixteenth century writers claim about her is true, she must have had her fair share of both mettle and misfortune. Though she never saw her husband again, her two children by Thomas Boyd were eventually allowed to return to Scotland and, in the early 1480s, young James Boyd was even allowed to succeed to his grandfather’s title of Lord Boyd, possibly through his mother’s political influence. Norman MacDougall has raised the possibility that the young Boyd- then only in his early teens- returned to Scotland in 1482 in the company of his uncle Alexander, Duke of Albany, who had invaded Scotland with Richard, Duke of Gloucester and an English army. Since James III wasn’t entirely free to govern as he liked during this troubled period, MacDougall suggests that Mary Stewart may have seen her chance to rebuild the Boyd patrimony in Ayrshire. The fact that the grants of land made to James Boyd (several of which which Mary received liferent of) were part of the queen’s dower and supposedly could not be alienated meant that the grants were semi-illegal, and unlikely to have been made by the king acting on his own initiative. But James Boyd’s career was destined to be brief and when his uncle Alexander fled to Dunbar in 1483, the nephew followed and the grants made to him were rescinded. The following year, the young James (who could not have been much older than fifteen) was killed by Hugh Montgomery of Eglinton, sparking a local feud in Ayrshire between the Boyds and the Montgomeries which lasted over a century.

Mary was only in her early thirties but she had already lost two husbands and was now left to bury her teenaged son. Of her four siblings, only two remained by 1488, since John, Earl of Mar, had perished in mysterious circumstances in royal custody in 1479 and Alexander, Duke of Albany met his end in 1485, when he was hit by a splinter from the lance of the Duke of Orleans (the future King Louis XII) during a tournament in France. However, Mary did not live long enough to see the death of her last brother James III at the Battle of Sauchieburn in June 1488, since she herself seems to have died earlier that year, aged around 37.

Her posthumous legacy, as with so many other women of her time, has generally been seen in terms of the later prospects of her offspring. The descendants of her two children by Lord Hamilton were destined to play an important role in the fraught politics of sixteenth century Scotland. From her son James Hamilton were descended the Earls of Arran, including the Regent Arran who governed Scotland on behalf of the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, by virtue of his position as “second person of the realm” and the little queen’s direct heir through his descent from her great-great aunt and namesake. Mary’s younger daughter Elizabeth Hamilton married Mathew Stewart, Earl of Lennox, and Elizabeth’s grandson the 4th Earl of Lennox would later challenge the claims to the throne of his cousin the Regent Arran, creating a rivalry at the very heart of Scottish politics. Margaret Boyd, the only surviving child of Mary’s first marriage, married first Lord Forbes and then returned to Ayrshire to marry the first Earl of Cassilis. Although Mary Stewart herself remains a shadowy figure to this day, her story- both factual and speculative- has attracted interest and sympathy throughout the centuries and still offers opportunities for further discovery.

Additional notes and references below the cut.

Edit: the ‘read more’ section isn’t showing up on a lot of versions of this, so I will just have to put all the notes and sources below, even though it’s messy:

* In the twentieth century there was quite a bit of debate over the correct dates of birth for James III and Mary. Despite what is on wikipedia, this has largely been resolved and the general consensus is that Mary was the elder sibling.

** Some historians have debated whether Mary’s marriage prospects were quite so important to the political community in 1467 as has been traditionally assumed, but the Stewart dynasty’s contemporary European marriage alliances are nonetheless important to bear in mind.

*** Lord Boyd’s two younger sons were spared the king’s wrath however, and the youngest of them, Archibald Boyd of Naristoun, was the father of Marion Boyd, a mistress of James IV.

**** In all fairness though, we have so few contemporary chronicles/histories for the reign of James III that we have to take the sixteenth century writers at their word sometimes, especially where they agree with each other. Nonetheless we should always be cautious.

**** It’s worth noting that the site of the George in Lombard street in London is still occupied today, since there has been an inn on the spot since the twelfth century and its current incarnation is an eighteenth century building housing the George and Vulture restaurant. It seems that several of the buildings of Anselm Adornes’ estate where the Boyds were housed in Bruges also still exist, though I will have to do more research on this.

References (I have included links to online versions where available):

- “The Date of the Birth of James III”- there are two articles by this name in the Edinburgh Historical Review for the years 1950 and 1951 respectively, and both of them were consulted. The author of the first was Annie I. Dunlop while corrections and debate between Dunlop and Dr William Angus comprise the second.

- “James III”, by Norman MacDougall

- “Power and Propaganda: Scotland, 1306-1488″, by Katie Stevenson

- “The Boyds in Bruges”, W.H. Finlayson

- “A Letter of James III to the Duke of Burgundy”, C.A.J. Armstrong

- John Lesley’s “The Historie of Scotland”

- This translation of George Buchanan’s “History of Scotland”

- “Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland”, vol. 1

- “The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland”, vol. 5

- “Register of the Great Seal of Scotland”, vol. 2

- “Vetera monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum historiam illustrantia...”, Augustin Thenier

- “The Paston Letters”, vol. 3, edited by James Gairdner

- Giovanni Ferreri’s continuation to Boece I had to use the translation from this website since I couldn’t get access to the 1574 printing any other way, though my reading is backed up by secondary sources.

#This was not my best edit I may redo it later#My sources are pretty decent though so proud of that#women in history#British history#History edits#But had to get the word out about Mary- apologies for the length when I know there's not much definite info on her but context is important#Also James III and his siblings were a bonfire of insanity- Mary actually got off comparatively lightly#I don't know what was in the air in the 1470s- the York brothers were just as bad and on the continent there's a fair few similar cases#the Stewarts#shoddy history gifsets#Mary Stewart Countess of Arran

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victims of the Childbed - Elizabeth of York, Queen of England

Often referred to as the daughter, sister, niece, wife, and mother of a king. Elizabeth of York was the first Tudor queen of England. Her influence was quiet but always present, and her sudden death left a king and country bereft.

Much, much more below the cut:

From the moment of her birth, Elizabeth of York was enveloped in a large and, unusually so for the era, close knit royal family. She was named after her mother, the beautiful Queen Elizabeth Woodville. Her father, Edward IV of England, was a giant of a man both in person and persona. Edward had won the English crown five years prior to Elizabeth’s birth and would fight to retain it throughout her childhood. Princess Elizabeth was one of the first children born into a new generation of the House of York. She was the firstborn of the new king and his consort and though the birth of a son had been predicted, she was still welcomed by her parents and doted on at their merry court. Edward IV’s account book for 1466, the year of Elizabeth’s arrival, records the purchase of a jeweled ornament “against the time of the birth of our most dear daughter Elizabeth.”

The young Elizabeth was soon followed by two sisters, Mary and Cecily. In addition, the princesses also had two elder half-brothers, Thomas and Richard Grey, born of Elizabeth Woodville’s first marriage. Queen Elizabeth preferred to keep her children near her at court, as well as members of her own large family. As a result, Elizabeth of York enjoyed the close company of her siblings and Woodville relations for the rest of her life.

It was the influence of the Woodville family at court and their involvement in politics which contributed to a boiling over of tensions between Edward IV and his cousin and adviser Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who allied himself with Edward’s brother George, Duke of Clarence. Warwick and Clarence rebelled against Edward, forcing him to flee into exile on the continent. The rebellion claimed the lives of four-year-old Elizabeth’s maternal grandfather and uncle, Richard and John Woodville, who were executed by Warwick. The rebellion would be the little princess’s first experience with the traumatic and deeply personal world of politics in late medieval England. Queen Elizabeth took her children into sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, where she gave birth to Elizabeth’s brother Edward, the future ill-fated Edward V. This would not be the only time Princess Elizabeth would find herself in sanctuary at the Abbey during uncertain times.

Edward IV’s restoration to power in the spring of 1471 also restored domestic peace for a time. He brought his family out of sanctuary and Elizabeth of York re-assumed her place as “Elysabeth the Kyngys Dowther.”

Elizabeth of York was well educated. She became fluent in both English and French and could perhaps write better than was expected for noblewomen of her day. Her maternal family, the Woodvilles, were a literary bunch. Books were shared among Elizabeth, her siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles. King Edward maintained an impressive library and often purchased new volumes and illuminated manuscripts to add to his collection, which his daughter no doubt enjoyed perusing. As well as an appreciation for the written (and newly printed, thanks to Caxton and his press, which her family avidly supported) word, Princess Elizabeth also cultivated a love of music and dancing. She learned to play several instruments and is recorded dancing with her father as early as the age of six. Elizabeth would pass on this passion for musical persuits to her children, namely her son Henry VIII, whose own compositions are still known today.

By 1480, Elizabeth was the eldest of ten royal children, eight of whom survived infancy. In addition to her two half-brothers, Elizabeth’s parents kept quite a brood. For the most part, Elizabeth’s childhood had been a happy one, but her early adulthood would prove to be very different. On April 9, 1483, Edward IV died suddenly, leaving his twelve-year-old son as King Edward V. The boy’s youth was potentially dangerous, as Queen Dowager Elizabeth was well aware, as were her enemies. Distrust was rampant among the rival factions at court and conflict soon erupted as it often did in 15th century England. Princess Elizabeth’s uncle, Edward IV’s youngest brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, took control of the boy king from Sir Anthony Woodville. The Queen Dowager acted decisively and once again fled to the sanctuary of Westminster Abbey with her daughters and remaining son, Prince Richard, who was soon taken to the Tower of London with his brother.

Elizabeth, now seventeen, stayed in sanctuary with her mother for almost a year, her future prospects dwindling. During that time her remaining family received one tragic blow after another. Richard of Gloucester seized control over the realm. Both the young Edward V and Prince Richard were locked away in the Tower and soon disappeared altogether, their fate an enduring mystery. Gloucester executed Elizabeth’s beloved uncle, Anthony Woodville and her brother Richard Grey. To fully consolidate his power, Gloucester declared the children of Edward IV by Elizabeth Woodville illegitimate. Princess Elizabeth was now traumatized and bastardized with little hope for what lay ahead.

In early 1484, however, the new King Richard III persuaded the Queen Dowager to allow Elizabeth to return to court. Elizabeth and her sister Cecily joined the household of Queen Anne Neville. Her life doubtlessly improved once she was away from the bleak seclusion of Westminster. Eighteen-year-old Elizabeth was one of the greatest beauties at Richard’s court, and soon rumors were circulating that the king intended to wed his lovely and charming niece. Queen Anne’s declining health and subsequent death only increased the suspicion surrounding Elizabeth and Richard’s relationship. Richard was eventually obliged to send Elizabeth to Sheriff Hutton Castle in Yorkshire along with Cecily and their cousins Margaret and Edward, Earl of Warwick, the children of the Duke of Clarence. Elizabeth’s thoughts on her uncle, the fate of her brothers, or indeed most of the momentous events of her life are often speculated but still remain quite unknown.

The subject of Elizabeth’s marriage had been controversial for some time at this point. Her hand was promised several times for various political expedient reasons. At the age of nine she was formally betrothed to the Dauphin of France and was called “Madame la Dauphine” in her adolescence. But the betrothal was broken by a rather slippery King of France not long before Edward IV’s death.

Following Richard’s declaration of her illegitimacy, the potential for a glittering match seemed dim. But Elizabeth Woodville had allied herself with Margaret Beaufort and together, using a physician as a messenger, the two ladies would work towards supplanting Richard. Margaret’s son Henry Tudor, nephew of the late Henry VI, had spent half of his life in exile as the last Lancastrian heir. Aside from Richard III, according to the laws of primogeniture, Elizabeth of York was the Yorkist heir to Edward IV in the absence of her brothers. A union between the two would perhaps remedy the rift between the two houses made by the Wars of the Roses, at least partially satisfying both sides.

While Elizabeth was residing at Sheriff Hutton, Henry Tudor landed in England and met Richard’s army at Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. The battle’s end found Richard III dead and Henry with the English crown. He had won his right in battle, but Henry Tudor’s claim to the throne was rather shaky. He was a descendant of Edward III only through his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, through the bastard line of John of Gaunt. Elizabeth of York, though still legally bastardized herself, also descended from Edward III, but through a legitimate male line. Thus it seemed that Henry Tudor would need her to lend stability to his throne, though he would forever fight to conceal it. Henry was crowned Henry VII on October 30, 1485 and immediately set about establishing his authority in his own right. England was an uncertain nation in need of stability, but that was difficult to achieve with so many Yorkist claimants and their adherents at large.

The generation of Yorkists to which Elizabeth belonged was largely female, and for the next decade Henry would neutralize the threat they posed through marriage. Elizabeth of York, as the eldest surviving child of Edward IV, was regarded by many to be the rightful heir to his throne. Certainly no one expected Elizabeth to be queen regnant of England; the country was still not ready for such a concept. Once Henry Tudor was crowned and his first Parliament opened, Elizabeth’s legitimacy was reestablished. Finally, with the proper papal dispensation in acquired, Henry and Elizabeth were formally betrothed.

Elizabeth of York became Queen of England when she married Henry VII on January 18, 1486. It has been suggested that Henry put off the marriage as long as possible to establish his rule in his own right without seeming to have accepted help from Elizabeth. Regardless, she would bring his reign stability that he could not have gained on his own. As queen, Elizabeth is not known to have taken an active role in political matters. She had been brought up to play the traditional role of a consort, which she did perfectly. Her kindness, generosity, and gracious nature were renowned. She was also known for her beauty, golden hair, and fine figure. She surrounded herself with her dearest relatives, most of whom were well provided for in her lifetime.

The relationship between Elizabeth of York and Henry VII has been popularly portrayed as a love match. It was a marriage of political necessity which over time seems to have grown into a partnership of mutual respect and affection. Henry’s accounts show him buying small gifts and trinkets for his wife, and Elizabeth’s show that she undertook tasks such as sewing Henry’s garter mantle when she was not required to do so herself. There were still political aspects to the marriage. Elizabeth never had the financial independence enjoyed by most consorts, possibly because Henry never entirely got over an innate distrust of all things Yorkist.

Elizabeth’s influence on the world of Tudor aesthetics that has fascinated many for five centuries may have been greater than previously assumed. Tudor pageantry was impressive, outlandish, and extravagant. The pageant stages, disguisings, and masques were inspired by Burgundian entertainments. Who had more experience with this style of revelry than she who had grown up at the center of a court heavily influenced by the court of Burgundy? From her infancy, Elizabeth would have been familiar with Burgundian style due to her own heritage through her maternal grandmother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg. The pageantry Elizabeth so enjoyed became a hallmark of Tudor entertainment. Tudor architecture, too, is thought to have some touch of Burgundian influence. Elizabeth of York is documented as being involved in at least the rebuilding of Greenwich Palace, a distinctly Tudor royal residence.

The marriage of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII was certainly successful in regard to their offspring. Elizabeth gave birth to their first child, a son and heir, only eight months after their wedding in 1486 (leading to speculation of consummation before the public wedding ceremony). The prince was christened Arthur and was greeted with national rejoicing. Princess Margaret followed three years later in 1489. Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth, who died at the age of three, were born in 1491 and 1492. Another daughter, Mary, was born in 1496. Elizabeth may have given birth to a short lived boy named Edward, or this could be a confusion with Prince Edmund, who died in infancy.

Elizabeth of York, like her own mother, was devoted to her children. As the heir to the throne, Prince Arthur was set apart from his siblings with his own household and rigorous education. The younger children lived near their parents at Eltham Palace, where they were frequently visited by their mother. Elizabeth doted on her fair daughters and boisterous son Henry, who took after his grandfather, Edward IV.

Prince Arthur was married to Katherine of Aragon in November 1501 in a lavish ceremony. The teenage couple was sent to Wales to hold court as the future king and queen of England. Their future and the succession seemed secure until an unforeseen disaster occurred. On April 2, 1502, only five months into his marriage, the fifteen-year-old Prince Arthur suddenly died, possibly of the sweating sickness. Elizabeth and Henry grieved the loss of their son both as monarchs and as parents. But Elizabeth attempted to console her husband by reminding them that they still had a healthy son and were still young enough to have more children. They were indeed young enough to produce another heir to secure the Tudor Dynasty, and Elizabeth became pregnant with her seventh child soon afterwards. The queen spent the remainder of 1502 mourning her son and traveling in England and Wales. She experienced some health issue, but it is not known if it was pregnancy related.

Elizabeth of York gave birth to her last child, a daughter, at the Tower of London on February 2, 1503. This baby may have been premature, as Elizabeth had not withdrawn from court to take to her chamber in preparation of the birth. In fact, she had traveled from Richmond to London only a week prior to the birth. For her previous births, Elizabeth had observed the rituals and preparations laid out by Margaret Beaufort in her ordinances for royal births. For this birth it seems almost nothing had been prepared, and one chronicle claims Elizabeth had intended to give birth at Richmond. Instead she delivered her daughter at the Tower of London. While the baby princess was quickly baptized Katherine, her mother became ill. Elizabeth had contracted childbed fever, or puerperal fever and was not strong enough to fight off the infection. She succumbed to her illness and died on February 11, 1503, her thirty-seventh birthday. Princess Katherine had died the day before.

The royal family and country were plunged into grief. Elizabeth was given a funeral fit for a queen. Henry VII was much altered by the loss of his wife and two children in under one year. The illuminated manuscript Vaux Passional contains an illustration of Elizabeth’s bereft family. A rather sullen Henry VII is shown wearing the blue robes of royal mourning. The princesses Margaret and Mary wear black veils. Most moving of all is the image of eleven-year-old Prince Henry weeping on his mother’s empty bed. King Henry never dismissed Elizabeth’s court minstrels and continued to pay them until his death in 1509.

Elizabeth of York was all but canonized in death. She was remembered as “one of the most gracious and best beloved princesses in the world in her time being.” She was the silent guiding hand behind Henry VII, the first Tudor queen from whom descended the next four Tudor monarchs as well as the Stuarts. Elizabeth of York also left her mark through the red-gold hair she passed on to her son Henry VIII and granddaughters, Mary and Elizabeth, queens regnant of England.

Arlene Naylor Okerlund, “Elizabeth of York”

Kavita Mudan Finn, “The Last Plantagenet Consorts: Gender, Genealogy, and Historiography, 1440-1627”

#we are all so fortunate for read more links#this thing just spiraled out of control#the more I researched the more stuff I just couldn't NOT include#she's one of my favorite historical ladies can't you tell#I also deliberated over the gown#she always gets drawn in that one red gown#but I thought blue might be nice#it's also the color of royal mourning which is appropriate#Elizabeth of York#Henry VII#Tudor#england#victims of the childbed#art#my art

233 notes

·

View notes