#Mikhail Yuriev

Text

News of money previously given to House Speaker Mike Johnson's congressional campaign by Russian nationals has re-emerged after the Republican rejected a $95 billion foreign aid bill passed in the Senate.

In 2018, a group of Russians were able to donate to Johnson's bid for the Louisiana seat he eventually won as the money was funneled through the Texas-based American Ethane company.

While American Ethane was co-founded by American John Houghtaling, at the time it was 88% owned by three Russian nationals—Konstantin Nikolaev, Mikhail Yuriev, and Andrey Kunatbaev. Nikolaev is known to be a top ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

A spokesperson for Johnson previously assured in 2018 that the campaign returned the money that was given to them by American Ethane once it was "made aware of the situation." There was no indication that Johnson's campaign team willfully broke federal law, which makes it illegal for a campaign to knowingly accept donations from a foreign-owned corporation, a foreign national, or any company owned or controlled by foreign nationals.

A number of social media users have now brought up the campaign money amid Johnson's opposition to the long-debated foreign aid bill, which would send $60 billion to Ukraine as the country continues to fight off Russia's invasion.

In a press conference on February 14, Johnson said he would not bring the bill recently passed by the Senate back from a House vote and that the "Republican-led House will not be jammed or forced into passing" the foreign aid bill.

The same day, Ukraine-based blog Fake Off posted on X, formerly Twitter: "US Speaker of the House Mike Johnson received campaign contributions from American Ethane, a company 88% owned by three Russians. Now, do you understand why he was categorically against the aid to Ukraine?"

Another social media user added, while sharing a clip of Johnson's press conference: "Astonishing that the Speaker of the House for the United States Government accepts money from Russia. Konstantin Nikolaev, Mikhail Yuriev, and Andrey Kunatbaev own 88% of American Ethane."

Johnson's office has been contacted for comment via email.

WHO IS KONSTANTIN NIKOLAEV?

The 52-year-old is a billionaire who previously served as minister of transport for the Russian Federation.

Nikolaev and his two partners currently own a third of Globaltrans, Russia's biggest private rail transport operator, and he previously worked in railroad freight and port businesses.

He is also a part owner of Tula Cartridge Works, which has been supplying ammunition for Russian forces during its invasion of Ukraine.

In 2019, Forbes listed the oligarch's net worth at $1.2 billion.

Nikolaev is also known for being a financial backer of Maria Butina, a Russian citizen who was sentenced to 18 months in prison in 2019 after admitting to acting as an unregistered foreign agent to infiltrate conservative political groups and influence foreign policy to Russia's benefit before and after the 2016 election.

The money that Nikolaev and the other two Russian nationals managed to donate to Johnson's 2018 campaign was also brought up after the Republican was elected House Speaker last October.

"Putin pal Konstantin Nikolaev, who handled Russian spy Maria Butina, was also the principal stockholder in American Ethane Co. when they donated over $37,000 to Mike Johnson's election campaign. Does anyone else think that might be a problem?" posted X user @Davegreenidge57.

#us politics#news#republicans#conservatives#gop#speaker of the house#rep. mike johnson#russia#foreign lobbiest#American Ethane#Konstantin Nikolaev#Mikhail Yuriev#Andrey Kunatbaev#Vladimir Putin#campaign donations#foreign aid bill#Russian Federation#Tula Cartridge Works#Maria Butina#newsweek#2024

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day, I included a link to an article in The Atlantic titled Putin is just following the manual: A utopian Russian novel predicted Putin’s war plan. “If you read only one article today,” I wrote, “make it this one.”

The author, Dina Khapaeva, is the director of the Russian studies program at Georgia Tech’s School of Modern Language. Monique Camarra and I spoke to her on the Cosmopolicast about the article, which begins this way:

No one can read Vladimir Putin’s mind. But we can read the book that foretells the Russian leader’s imperialist foreign policy. Mikhail Yuriev’s 2006 utopian novel, The Third Empire: Russia as It Ought to Be, anticipates—with astonishing precision—Russia’s strategy of hybrid war and its recent military campaigns: the 2008 war with Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea, the incursion into the Donetsk and Luhansk regions the same year, and Russia’s current assault on Ukraine.

It is, apparently, “the Kremlin’s favorite book.”

Yuriev was the chairman of the Russian Government’s Council on Economy and Entrepreneurship and a deputy speaker of the State Duma. I wasn’t able to read the novel in full, because it hasn’t been translated into English at all. I was only able to read a few extracts that have been translated to French.

But as we discuss in the podcast, those extracts, along with Dina’s commentary, still offer significant insights into modern Russia and its ideological commitments. If John Mearsheimer and his coterie were aware of this book, perhaps they would have thought twice about confidently advancing the thesis that NATO’s expansion provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The discussion is especially timely in light of the assassination of Darya Dugina, whose father is a prominent exponent of this ideology.

I’ve argued before in this newsletter that the West is at a tremendous disadvantage in its analysis of modern Russia because we refuse to take its culture seriously, and in particular, because we refuse to recognize that it is in the grip of an ideology as significant and as dangerous as Soviet communism. It’s as if having seen off Soviet Union, we collectively determined that we’d invested enough time and energy trying to understand that benighted place and refused to do it again. Now, over and over, I hear one or another politician or columnist insist that the threat Russia now poses is nothing like the threat we confronted in the Soviet Union because the Soviet Union was a communist empire, whereas modern Russia is not. The suppressed premises of this argument are false.

It is true that a communist super-state poses an inherent threat to a capitalist one—as we perfectly understood during the Cold War—because to subscribe to the ideology, at least as the Bolsheviks understood it, is to understand oneself to be at war with the capitalist world. Just as you cannot be a Christian without believing in the resurrection of Christ, you could not be a Bolshevik without seeking to overthrow the capitalist state system, seize power, and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat. We understood from studying Bolshevik writings, speech, and behavior that so long as men who ascribed to this ideology remained in power, the USSR would endeavor implacably to overthrow our governments and replace them with totalitarian dictatorships—and if, in reality, a “dictatorship of the proletariat” amounted to nothing grander than a particularly immiserated dictatorship, it was because the theory was wrong, not because its exponents failed sincerely to ascribe to it.

Understanding Bolshevism was key to understanding the Soviet Union and thus key to mounting an effective defense against its expansion. Had we persuaded ourselves that its ideology was insignificant—that the USSR had no global ambitions—our response to it would have been inadequate. Had we accepted (as indeed some argued) that the Soviet Union was swiftly imprisoning one after another country behind the Iron Curtain because its conception of its security demanded this, we wouldn’t have conjured up a globe-spanning series of alliances to contain it. Senator Vandenberg would not have said, “Politics stops at the water’s edge” and cooperated with the Truman administration to forge durable, bipartisan support for the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, NATO, SEATO, and CENTO. The Soviet Union would have continued to expand, enslave, and immiserate many more millions before it collapsed—if indeed it ever collapsed.1

The sources of American conduct may be found in George Kennan’s 1947 telegram, The Sources of Soviet Conduct. He wrote:

The political personality of Soviet power as we know it today is the product of ideology and circumstances: ideology inherited by the present Soviet leaders from the movement in which they had their political origin, and circumstances of the power which they now have exercised for nearly three decades in Russia. There can be few tasks of psychological analysis more difficult than to try to trace the interaction of these two forces and the relative role of each in the determination of official Soviet conduct. Yet the attempt must be made if that conduct is to be understood and effectively countered. [My emphasis, as is all bold text below.]

It is worth rereading that telegram. It’s hard to imagine that an equally lucid document is now circulating among our national security apparatus. One lives in hope, but the Long Telegram is so much more intelligent and better written than any government document I’ve seen in recent years that I can’t quite bring myself to believe it.

Kennan understood that the Soviet leaders’ ideology reflected the pathologies of Tsarist Russia. “From the Russian-Asiatic world out of which they had emerged [the men in the Kremlin] carried with them a skepticism as to the possibilities of permanent and peaceful coexistence of rival forces.” And he understood what this implied for the rest of the world:

[T]he men in the Kremlin have continued to be predominantly absorbed with the struggle to secure and make absolute the power which they seized in November 1917. They have endeavored to secure it primarily against forces at home, within Soviet society itself. But they have also endeavored to secure it against the outside world. For ideology, as we have seen, taught them that the outside world was hostile and that it was their duty eventually to overthrow the political forces beyond their borders. The powerful hands of Russian history and tradition reached up to sustain them in this feeling. Finally, their own aggressive intransigence with respect to the outside world began to find its own reaction; and they were soon forced, to use another Gibbonesque phrase, “to chastise the contumacy” which they themselves had provoked. It is an undeniable privilege of every man to prove himself right in the thesis that the world is his enemy; for if he reiterates it frequently enough and makes it the background of his conduct he is bound eventually to be right.

What, concretely, did this ideology imply? It had, wrote Kennan, “profound implications for Russia’s conduct as a member of international society.”

It means that there can never be on Moscow’s side any sincere assumption of a community of aims between the Soviet Union and powers which are regarded as capitalist. It must invariably be assumed in Moscow that the aims of the capitalist world are antagonistic to the Soviet regime, and therefore to the interests of the peoples it controls. If the Soviet government occasionally sets its signature to documents which would indicate the contrary, this is to be regarded as a tactical maneuver permissible in dealing with the enemy (who is without honor) and should be taken in the spirit of caveat emptor. Basically, the antagonism remains. It is postulated. And from it flow many of the phenomena which we find disturbing in the Kremlin's conduct of foreign policy: the secretiveness, the lack of frankness, the duplicity, the wary suspiciousness and the basic unfriendliness of purpose. These phenomena are there to stay, for the foreseeable future. There can be variations of degree and of emphasis. When there is something the Russians want from us, one or the other of these features of their policy may be thrust temporarily into the background; and when that happens there will always be Americans who will leap forward with gleeful announcements that “the Russians have changed,” and some who will even try to take credit for having brought about such “changes.” But we should not be misled by tactical maneuvers. These characteristics of Soviet policy, like the postulate from which they flow, are basic to the internal nature of Soviet power, and will be with us, whether in the foreground or the background, until the internal nature of Soviet power is changed.

The saving grace, Kennan argued, was that the Kremlin was not in a hurry. “Like the Church, it is dealing in ideological concepts which are of long-term validity, and it can afford to be patient.”

Its main concern is to make sure that it has filled every nook and cranny available to it in the basin of world power. But if it finds unassailable barriers in its path, it accepts these philosophically and accommodates itself to them. The main thing is that there should always be pressure, unceasing constant pressure, toward the desired goal. There is no trace of any feeling in Soviet psychology that that goal must be reached at any given time.

These considerations make Soviet diplomacy at once easier and more difficult to deal with than the diplomacy of individual aggressive leaders like Napoleon and Hitler. On the one hand it is more sensitive to contrary force, more ready to yield on individual sectors of the diplomatic front when that force is felt to be too strong, and thus more rational in the logic and rhetoric of power. On the other hand it cannot be easily defeated or discouraged by a single victory on the part of its opponents. And the patient persistence by which it is animated means that it can be effectively countered not by sporadic acts which represent the momentary whims of democratic opinion but only by intelligent long-range policies on the part of Russia’s adversaries—policies no less steady in their purpose, and no less variegated and resourceful in their application, than those of the Soviet Union itself.

In these circumstances it is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.

There it is: The concept that for the next 43 years was to guide American foreign policy, accepted by both parties and executed so successfully that the Soviet Union collapsed—not, as is often and stupidly said, “without a shot fired” (and not by any means), but without, at least, a nuclear exchange.

The telegram was brilliant in several respects. Not only was it correct (a great virtue in a policy document), it was brilliantly written, in that it conveyed complex and alien ideas in so lucid a manner that every American understood it, and thereafter (for the most part) lent their support to the policies it entailed.

No similar understanding guides American foreign policy today, or if it has, it hasn’t been shared with the public. Our policy toward Russia has been so confused, inconsistent, and indifferent that it is hard to imagine it conforms to any overarching logic, no less a sound and considered one.

Nor does politics stop at the water’s edge. When Mitt Romney proposed that Russia was our primary geopolitical adversary, Obama sneered. Romney was right, but it is no good being right if you can’t articulate your case in a way that Americans understand. What he said made no sense to them: The Soviet Union had, after all, collapsed, and we were mired in any number of wars with countries that clearly weren’t Russia. Why should our relationship with Russia be adversarial?

Trump exploited this confusion by insisting that NATO was “obsolete.” Nothing, he insisted, prevented him from having “a great relationship” with Russia. If he’s reelected (God forbid), he would presumably say the same thing and behave the same way, a prospect at this point almost too horrifying to contemplate. A significant fraction of the American public would once again thrill to the prospect of “getting along with Russia.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruzzian ex-minister, Putin ally and oligarch arms manufacturer Konstantin Nikolaev helped fund US speaker Mike Johnson's election campaign - Newsweek

In 2018, a group of Russians were able to donate to Johnson's bid for the Louisiana seat he eventually won. The money was funneled through the Texas-based American Ethane company.

At the time it was 88 percent owned by three Russian nationals—Konstantin Nikolaev, Mikhail Yuriev, and Andrey Kunatbaev. Nikolaev is known to be a top ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Konstantin Nikolaev is a 52-year-old ruzzian billionaire who previously served as minister of transport for the Russian Federation.

He is a part owner of Tula Cartridge Works, which has been supplying ammunition for Russian forces during its invasion of Ukraine.

A spokesperson for Johnson stated that the campaign returned the money that was given to them by American Ethane once it was "made aware of the situation."

There was no indication that Johnson's campaign team wilfully broke federal law, which makes it illegal for a campaign to knowingly accept donations from a foreign-owned corporation, a foreign national, or any company owned or controlled by foreign nationals.

1 note

·

View note

Note

2 3 9 12 17

2. did you reread anything? what?

yeah. after all those years i can confirm that eugene onegin slaps as hard as it did when i first read it. i also turned to grigory dashevsky's and mikhail kuzmin's poetry collections quite a lot for sentimental reasons.

3. what were your top five books of the year?

in no particular order:

- imeni takogo-to by linor goralik

- leningradskaya khrestomatiya by oleg yuriev

- wound (rana) by oksana vasyakina

- chaadaevskoye delo by mikhail velizhev

- technically not just one book but andrey voznesensky's poetry. britney.gif

9. did you get into any new genres?

yes! i finally started to pay more attention to contemporary theatre and read a lot of plays.

12. any books that disappointed you?

too many for my liking. guess i was expecting a lot more from alexey salnikov and didn't enjoy his latest okkulttregger as a result. also viktor pelevin? is... not my kind of guy to put it mildly. though i'm now obsessed with the clay machine gun theatre production i recently saw in moscow.

17. did any books surprise you with how good they were?

you could say imeni takogo-to surprised me with how it made me feel. i.e. absolutely horrible. but i physically wasn't able to put it down.

#thank you dear anon#just realized i haven't read any foreign authors in 2022...#apart from the academic things i had to suffer through to finish my thesis

0 notes

Photo

Reposted from @motherjonesmag Shocker. The Federal Election Commission recently let a US company that was quietly bankrolled by Russian oligarchs off with a slap on the wrist despite discovering that it had illegally funneled Russian funds to US political candidates in the 2018 midterm elections, two Democratic FEC commissioners said in a scathing statement issued this past Friday. “Half the Commission chose to reject the recommendation of the agency’s nonpartisan Office of General Counsel and turned a blind eye to the documented use of Russian money for contributions to various federal and state committees in the 2018 elections,” wrote the two commissioners, Ellen Weintraub and Shana Broussard. Anyone who follows campaign finance knows that the FEC has been toothless for years due to GOP commissioners’ opposition to any enforcement of laws designed to oversee money in politics. But Weintraub and Broussard suggest the agency hit a new low by letting the US firm, American Ethane, off with a deal in which it agreed to pay only a small civil fine. Though based in Houston, Texas, and run by American CEO John Houghtaling, 88 percent of American Ethane was owned by three Russian nationals—Konstantin Nikolaev, Mikhail Yuriev, and Andrey Kunatbaev. The FEC report said that Nikolaev, an oligarch and Russian billionaire with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, is the controlling shareholder. Separately, Nikolaev also underwrote efforts by Maria Butina, a Russian gun rights activist, to cultivate ties with National Rifle Association officials and with associates of Donald Trump around the time of the 2016 election. In 2018, Butina acknowledged acting as an unregistered Kremlin agent and pleaded guilty to participating in a conspiracy against the United States. She was sentenced to 18 months in prison but was deported six months later. According to lobbying disclosures, the company was seeking help from US officials in its efforts to sell US ethane to China. In 2018 it hired a US lobbying firm, Turnberry Solutions, with close ties to former Trump campaign chief Corey Lewandowski. And that's just the start of this web. Head to the link in our bio to read. https://www.instagram.com/p/CkcgBPgOP26/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

The first Russian Tsar of the House of Romanov, Mikhail was born on 22nd July (O.S. 12th July) 1596 in Moscow, Russia. He was the son of Feodor Nikitch Romanov (Patriarch Filaret) and Xenia Shestova (“great nun” Martha). He is the grandson of Nikita Romanovich Zakharyin-Yuriev, a prominent boyar of the Tsardom of Russia, and the brother to the first Russian Tsaritsa Anastasia, wife of Ivan the Terrible. As a young boy, he and his mother had been exiled to Beloozero in 1600.

At the age of 16, the poorly educated Mikhail was unanimously elected Tsar of Russia by a national assembly in 1613. His mother protested, believing and stating that her son was too young and tender for so difficult an office, and in such a troublesome time. He, too, wasn’t eager to accept such a role. His parents had suffered greatly during the Time of Troubles — his mother had been forced to become a nun and his father a monk. He eventually accepted the Russian throne, thus ending the Time of Troubles.

Mikhail Romanov was not particularly bright nor healthy. Short-sighted and suffered from a progressive leg injury, which resulted in his not being able to walk towards the end of his life. He was soft-natured, gentle and pious who gave little trouble to anyone and effaced himself behind his counsellors. His reign saw the greatest territorial expansion in Russian history. In 1645, fell ill and died on 23rd July, a day after his 49th birthday.

“On these difficult days, a boy was brought on a sledge across the dirty March roads to the charred walls of Moscow - a plundered and ravaged heap of ashes, only freed at great cost from the Polish occupants. A frightened boy elected tsar of Moscow, at the advice of the patriarch, by impoverished boyars, empty-handed merchants and hard men from the north and the Volga. The boy prayed and wept, looking out of the window of his coach in fear and dejection at the ragged, frenzied crowds who had come to greet him at the gates of Moscow. The Russian people had little faith in the new tsar, but life had to go on..." — Alexei Tolstoy

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let me make a list of every villain not killed by the protagonists.

Xenogears:

Ramsus - betrays other antagonists then gets taken in by the protagonists and sent to therapy.

Ramsus's 4 bodyguards - their alliance is Ramsus.

Emperor Cain - Betrayed

Krellian - Ascended to godhood

Miang - honestly I have no idea what happened. I'm confused.

Id - Makes peace with Fei and they become one

Grahf - redeemed and immediately heroicly sacrifices himself to take out a larger threat.

Xenosaga:

Albeido - he was taken out by Jr then he was revived and heroically sacrificed himself to take out a larger threat.

Yuriev - taken out by Albeido

Kevin - redeemed and immediately heroically sacrifices himself to take out a larger threat

Wilhelm - death by Kevin

Pelligri - Half counts, decided not to leave the exploding mech while Jin was yelling at her to get out.

Xenoblade 1:

Metal Face - a pillar from the sky stabbed him in the chest.

Gadolt - redeemed and immediately after heroically sacrifices himself to protect the party from a bomb.

Egil - redeemed and immediately after heroically sacrifices himself to take out a larger threat.

Tyrea - redeemed for a sidequest never to be seen again.

Xenoblade X:

Ga'Jiarg & Ga'Budhe - spared and become allies via sidequest.

Lao - fell in a VAT pool.

Luxaar - stabbed by Lao and fell in a VAT pool.

Xenoblade 2:

Mòrag & Brighid - became a party member on second encounter.

Bana - arrested by the police and forced to run on a hamster wheel for all of eternity.

Mikhail, Akhos, and Jin - redeemed and immediately after heroically sacrifices himself to take out a larger threat.

Patroka - surprise attacked by Amalthus.

Amalthus - death by Jin

#xenogears#xenogears spoilers#xenosaga#xenosaga spoilers#xenoblade chronicles#xenoblade spoilers#xenoblade chronicles x#xenoblade x spoilers#xenoblade chronicles 2#xenoblade 2 spoilers#my ironic fav in each game is Krellian Wilhelm Metal Face Lao and Bana

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Orb and Scepter of Tsar Alexei l of Russia.

•Orb ~ Istanbul,Turkey 1662. Belonged to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich I.

•Sceptre ~ Instanbul,Turkey 1658. Belonged to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich I. Аppearance of the new sceptre and orb in the Russian treasury is connected with the name of the new Tsar - Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, the son of Mikhail Feodorovich. Romanov. The place of creation was Istanbul, the capital of the Islamic state. It must have been caused by the fact the majority of first-class Istanbul jewelers were Greek, whose art was well-known and appreciated in Russia. The political point may have been the most important. Istanbul of the XVIIth century- was the former Constantinople, the former heart of the Orthodox World, named the second Rome by Russian writers in the late XVth century. That time, they called Moscow the heir to Byzantium, the third and the last Rome. In the reign of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich I, the political doctrine of Ivan II's epoch became popular, and the royal order hinted it. According to the date on the scepter, it was executed in 1658. There is a legend, it was presented to the Tsar by a Greek Ivan Anastasov. In archives there are records the orb with already mentioned barmas were brought to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich by a Greek, Istanbul citizen, Ivan Yuriev in 1662

0 notes

Text

Golden Ring of Russia - Travel Guide

New Post has been published on https://giveuselife.org/golden-ring-of-russia-travel-guide/

Golden Ring of Russia - Travel Guide

WHAT IS IT: The so-called “Golden Ring of Russia” is a symbolical ring connecting historical towns and cities to the North-West of Moscow. They represent 1,000 years of rich Russian history written in stone and wood, from an 850-year old church in Rostov to a 19th-century log house in the Suzdal’s open air museum. Each of the “golden” towns once played an important role in the history of Russia and was connected in one way or another with famous historical figures such as Alexander Nevsky, Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great and many others.

WHAT TO SEE: The cities and towns of the Golden Ring are listed here in alphabetical order:

Aleksandrov (founded in 1530, population 68,000) – The town is situated 100 km from Moscow on the crossway of ancient roads from the largest historic centers of Russia – Vladimir and Suzdal, Rostov and Yaroslavl, Sergiev Posad and Pereyaslavl-Zalessky. In 1564- 1581 the town was the residence of Ivan the Terrible. The very first in Russia publishing house was established in Aleksandrov in 1576. One of the leading textile manufacturing centers in Russia in the 19th century.

Bogolubovo (founded in 990, population 4,000) – a tiny quiet town near the city of Vladimir. The town was named after the Russian prince Andrey Bogolubsky (God-loving) who built the first fortified settlement here in 1165. Tourists can see remains of the Andy Bogusky’s residence including some residential chambers of the 12th century and the beautiful Church of the Intercession of the Virgin on the Nerl (1165) which is considered to be one of the finest specimens of old Russian architecture.

Groove’s (founded in 1239, population 30,000) – The town was founded under Vladimir prince Andrey Bogolubsky. The town is picturesquely settled on the high bank of the Klyazma River. Played the role as a fortified forest until 1600-s. Reached its developmental pick in the 17-th century as a local center for blacksmithing, textile-making, and making of leather and also as an agricultural trade center for grains and flax.

Gus-Khrustalny (founded in 1756, population 80,000) – Over 200 years ago a merchant built here the first workshop of glass casting. Today the town is one of the district centers of Vladimir region, well-known in Russia and abroad as the national center of glassmaking. The name Gus-Crustal can be literally translated as Crystalline Goose. The old part of the town is a workmen’s settlement of 1900-s. with its own Church of St. Joachim of 1816.

Kholuy (founded 1650, population 1,000) – The village of Kholui did not begin producing lacquered miniatures until the 1930s, and though iconography had been an important trade in the region in previous centuries, Kholui was never bound to any particular artistic tradition. Rather, Kholui miniatures share some traits with both Palekh and Mstera art, yet maintain a distinctive lyrical quality of their own. Sometimes, as with Palekh miniatures, Kholui miniatures will include some fine gold and/or silver ornamentation within the painting, and Kholui artists can create fantastic border ornaments on par with those of Palekh.

Kostroma (founded in 1213, population 300,000) – In the past Kostroma was known as “the flax capital of the north”; it supplied Europe with the world’s finest sail-cloth. The city has been also called as the “cradle of the Romanov dynasty”. Mikhail Romanov, the first of the Romanov dynasty, left the Ipatievsky Monastery for Moscow in 1613 to become tsar of Russia. During the Polish intervention in the turbulent years of the early seventeenth century, Kostroma was a significant stronghold for the resistance movement. Nowadays Kostroma is an important industrial center (textile, metal works), a capital city of the Kostroma province.

Master (founded in 1628, population 6,000) – the town takes its name from the little Osteria River, which flows through it merging with the Kliyazma. It is in Vladimir Region, but not far from the border with Ivanovo Region, south of Palekh and Kholui, in the breathtakingly beautiful countryside – the one that forms the backdrop to its paintings. Master was a respected center of icon production until the trade was banned after the Revolution of 1917. Since then its artists has been creating world-famous masterpieces in the form of lacquered miniatures.

Murom (founded 862, population 145,000) – one of the oldest Russian cities stretched along the left bank of the Oka river. The town’s name originates from “neuroma”, one of the Finno-Ugric tribes lived here 15 centuries ago. Every Russian knows the name Ilya Muromets. He was a mythical epic hero defending people of Russia and later became a synonym of superior physical and spiritual power and integrity, dedicated to the protection of the Homeland. The town survived three Mongol invasions. In the 17th century, Murom became an important center of various crafts – building, painting, sewing.

Palekh (founded 1600, population 6,000) – the village is situated about 400km (250 miles) from Moscow in the Ivanovo region. In the 15th century, it was one of the first centers of icon drawing trade. After the 1917 communist coup, when the icon business went down, Palekh masters tried to decorate wooden toys, dishes, porcelain, and glass. These days the name of Palekh is nearly synonymous with the art of Russian lacquer.

Pereslavl-Zalesskiy (founded in 1152, population 45,000) – one of the oldest Russian towns, the birthplace of the famous Russian prince Alexander Nevsky, who defeated an army of German knights in 1242. Zalessky means “behind the woods”. That is where, behind the dense forests, ancient Slavic tribes retreated seeking refuge from hostile nomads coming from the South-East.

Plus (founded in 1410, population 4,000) – this quiet little historical town is located on the bank of the mighty and beautiful Volga river. During the reign of Ivan, the Terrible Plus was one of the largest river fish suppliers to the kings’ court. In the 18-19th centuries, the town became known as a popular resort and was often called “Russian Switzerland” for the beauty of its scenery. Numerous Russian artists including the famous master of landscapes Levitan used to come here to work.

Rostov Veliky (Rostov the Great, founded in 862, population 40,000) – another pearl of ancient Russian culture. In old Russia, only two towns were called Veliky (great). One was Novgorod, the famous trade center of the Russia’s north, the other Rostov. In the 12th century, Rostov grew to equal Kiev and Novgorod in size and importance. Modern Rostov is a sleepy old town with some magnificent buildings next to the shallow Nero lake.

Sergiev Posad (founded in 1345, population 115,000) – the spiritual center of Russia, residence of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, where the remains of the first national saint, Sergei Radonezh, rests. In the heart of Sergiev Posad is a well-preserved splendid architectural ensemble of over 50 historical buildings, as well as magnificent art collections including old Russian painting and the treasures in the vaults of the former Trinity Monastery.

Suzdal (founded in 1024, population 12,000) – this little quiet town is a real gem, one of the most beautiful in the Golden Ring collection of cities and towns. In the 11th century, Suzdal became the very first foremost of Christianity in the North-Eastern Russia and significantly affected the religious life in Russia until the end of 19 century. Here you can find over 100 church and secular buildings dating from the mid-12th to the mid-19th century crowded into an area of 9 square km.

Uglich (founded in 937, population 38,000) – the town was built on a major trade route. In its history, Uglich has survived destruction by the Mongols and lived through the devastation of fires and plagues. Uglich is famous for Russia’s darkest secret – the death of young Prince Dimitri, son of Ivan the Terrible who is often called Tsarevich (an heir to the throne) Dmitry. The center of the town also is a historical and architectural landmark. The streets are wide, with various churches standing side by side along the road.

Vladimir (founded in 1108, population 400,000) – one of the oldest Russian cities, was founded by the Russian Prince Vladimir Monomakh on the banks of the Kliazma river. The city really blossomed in the 12th century during the reign of Prince Andrey Bogolubsky, who strengthened its defenses, welcomed architects, icon-painters, jewelers from other countries, built new palaces and churches so magnificent that travelers compared them with the ones in the “mother of all Russian cities”- Kiev. Until the middle of 14th century, the city had been an administrative, cultural and religious center for North-Eastern Russia.

Yaroslavl (founded in 1010, population 600,000 ) – as the legend goes it was founded by the famous Russian prince Yaroslav the Wise as a fortified settlement on the Volga river. After a huge fire of 1658 that turned most of the city into ruins, Jaroslavl was rebuilt in stone and reached the peak of its architectural development with palaces and churches richly decorated with beautiful frescoes and ornaments thus earning the title “Florence of Russia”. Today it is a quiet metropolitan city, one of Russia’s largest regional centers, a capital of the Jaroslav province and one of the most beautiful cities of old Russia.

Yuriev-Polsky (founded in 1152, population 20,000) – was founded by the Prince Yury Dolgoruky (who also founded Moscow in 1147) and named after himself. The second word “Polsky” means “among the fields” as it is situated in the heart of fertile and flat Suzdal land. These beautiful landscapes inspired the great painters and writers such as Repin, Tyutchev, Odoevsky, Soloukhin. Local textile center since the 18th century.

HOW TO GET THERE: By plane to Moscow. From Moscow, you can travel the cities and towns of the Golden Ring either by a tour bus or by a river cruise ship. The last option limits the number of towns that you can visit as they have to be situated close to the Volga river. We recommend you to take a bus tour for 3 to 10 days depending on your stamina and level of interest in Russian history. A typical 3-4-day tour from Moscow covers up to 7 cities and towns of the Golden Ring. You travel during the day time in a comfortable bus with a well-trained English-speaking guide and spend nights at hotels with Western-class service (usually- 3 star). The Golden Ring tour can be perfectly combined with 2-3 day program in Moscow. Almost every major travel agency in Moscow sells Golden Ring tours and it is much cheaper to buy them on the spot in Russia than to purchase a tour included into a vacation package from Europe or overseas. Communication is not a problem, these days all personnel in respectable agencies in Russia speak English.

WHEN TO GO: The best season to travel to Russia is summer, from June to August, the warmest time of the year there. Rains are usual during summers, do not forget to pack your umbrella. Weather can be unpredictable cold, even in the European part of Russia, so take some warm clothing. You can check next week weather forecast for Moscow here.

TRAVEL TIPS: A passport and a Russian visa are required to travel in or transit through Russia. To learn more about how to obtain Russian visa please visit Russian Embassy website. Without a visa, travelers cannot register at hotels and may be required to leave the country immediately via the route by which they entered, at the cost of the traveler. Russian customs officers strictly follow document regulations so travelers are advised to have all papers in order. It is also recommended that additional copies of passport and visa be kept in a safe place in case of loss or theft. Elderly travelers and those with existing health problems may be at risk due to inadequate medical facilities. Doctors and hospitals often expect immediate cash/dollar payment for health services at Western rates so supplemental medical insurance with specific overseas coverage is very useful. Travelers should be certain that all immunizations are up-to-date, especially for diphtheria and typhoid. The quality of tap water varies from city to city but normally is quite poor. Only boiled or bottled water should be drunk throughout Russia. Crime against foreigners in Russia continues to be a problem, especially in major cities. Pickpocketing, assaults, and robberies occur. Foreigners who have been drinking alcohol are especially vulnerable to assault and robbery in or around nightclubs or bars, or on their way home. Robberies may occur in taxis shared with strangers. Be aware that public washrooms are difficult to find, and usually you have to pay there. To use a public phone you will need a token or local card. International calls can not be made from street phones. Your mobile phone will work in Moscow and Saint Petersburg but seldom in regional cities. Taxi fee must be discussed with a driver before a journey.

In the major cities, you can rent a car if you do not mind fairly rugged road conditions, a few hassles finding petrol, getting lost now and then and paying high rent price. Public transport in Russia is quite good, cheap and easy to use though sometimes overcrowded. Restaurants seldom have a menu in English. Tipping is expected but not mandatory. Signs in English are common on the streets of Moscow and other big cities. In large cities, it is not hard to find a passerby who can answer your questions in Engish. Electricity throughout Russia is 220 volt/50 Hz. The plug is the two-pin thin European standard.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell us about the Romanov dynasty.

Sorry this took so long, I had to go to work and dig out all my texts on the subject. This is a three page Word doc, by the way, and I could have kept going.

Fair warning: Most of my knowledge aboutthe dynasty comes in about the time of Elizabeth Petrovna’s coup, overthrowingIvan VI. My early knowledge is a little sparse.

First, it’s important to understandwhy the Romanovs where so important. Besides being the last royal family ofRussia, they are what made Russia a superpower, and then kept it there.

The Romanov family shares a commonancestor with about twelve other noble Russian families, this ancestor beingAndrei Kobyla. He was kind of assigned a pedigree by later generations, becauseno one knew much about him. Common consensus was that he is the son of aPrussian prince names Glande, who came to Russia when fleeing the Germans.

HOWEVER, this guy’s last name means“mare”, and all his relatives bear names of animals, so it’s more likely hisfamily was employed in animal-rearing by a royal family in Prussia. Soon thesurname evolved into Koshkin (comes from a word for “cat”). This would becomeZakharin, and then would split into two branches: Zakharin-Yakovlev andZakharin-Yuriev.

When Ivan the Terrible was inpower, the Zakahrin-Yakovlev shortened their name to simply Yakovlev, and thegrandchildren of Roman Zakharin-Yuriev changed the family name to Romanov.

So. Thefirst Romanov monarch was Mikhail I. He was elected into the position of tsarby the Zemsky Sobor (Assembly of the Land, kind of like a parliament orcongress). Fun fact: his mother didn’t want him to accept the position, but theboyars more or less said “but then God will punish your son for destroyingRussia”, so she gave her blessing.

I don’tknow much about Mikhail’s reign, except that he did much to reform industry inRussia, including inviting in foreign manufacturers, such as Dutch gun-makersin Tula, which, even today, is noted for its gun manufacturing.

Mikhailwas succeeded by his only son, Alexei, who, although ascending to the throne atthe same age his father was, was much more experienced and ready to take thethrone.

His sonwas one of the most prominent Romanov leaders: Peter The Great. Peter the Greattruly modernized Russia, catching it up with its Western European counterparts.Under his rule, scientific research and rationalism prevailed, and he did awaywith many medieval and traditionalist policies.

Here’swhere things get interesting. Peter altered the tradition of succession so hecould name his own heir. This put the power in this hands of his second wife,Catherine. By 1730, with the death of Peter II, the male Romanov line had diedout.

Whatdoes this mean? Dynastic crisis!

PeterII was succeeded by Anna I, the daughter of Ivan V, Peter I’s half-brother. Shedeclared her grandnephew, Ivan VI, to be heir upon her death, which wouldsecure her father’s line and exclude descendants of Peter I.

At thetime of his ascension, Ivan VI was only a year old. His parents were put in asregent rulers, and everyone hated them, mainly because they had Germanconnections and counsel.

His “rule”was short. Elizabeth Petrovna, a legitimized daughter of Peter I, became popularamong the Russian populace, and dethroned Ivan VI in a coup d'état, supported by ambassadors from Franceand Sweden, and the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Ivan VI died in a prison riot.

This led to what is known as thehouse of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov, which held stake through matrilineal descentby relation to Peter the Great, via Anna Petrovna, his eldest daughter from hissecond marriage. Elizabeth brought Anna’s son, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp, toSt. Petersburg to declare him heir.

To ensure the future of theline, Elizabeth concocted a plot to bring Peter an heir. She set up a matchbetween him and a minor German princess, Sophia of Anhalt-Zerbst. She took thename Catherine after converting to Orthodoxy and endured an unhappy marriage toPeter. Soon after the death of Elizabeth, she overthrew Peter with the help ofher lover, Grigory Orlov.

AfterCatherine came Paul I, who held great pride in being a relation to Peter I,although his true father was almost certainly Sergei Saltykov, Catherine’ssecond lover.

Paul createdsome rather strict rules regarding succession of heirs for the house, includingthat all consorts must be of equal birth status and of the Orthodox faith.

Paul wasmurdered in 1801 and succeeded by Alexander I, who died before he could leavean heir. His younger brother, Nicholas I took the throne, but many Russiantroops swore allegiance to his older brother, Constantine Pavlovich, who hadprivately renounced his right to the throne years before. (This is what causedthe Decembrist revolt). The sons of Nicholas I would provide the last branchesof the family.

WhenAlexander II took over in 1855, the country was in the middle of the CrimeanWar. By developing the army, freeing the serfs, he gained a lot of support inthis time.

However, hisoldest son, Nicholas, died in 1864, and soon after, his wife died. After,Alexander decided to marry his mistress. This caused a problem with hislegitimate children, who worried he would crown her empress, and the childrenthey had would be legitimate heirs to the throne.

Lucky forthem, the Pan-Slavist movement was sweeping the nation, and Alexander II waskilled in a bomb attack. This movement had some interesting effects on Russiansociety in general, actually, but that’s another story. Let’s just say theRomanovs actually married Russians for a while, and not Germans (who also hadtheir own Pan-Germanic movement!)

Alexander IIIcomes into the picture now. He hadn’t expected to become tsar, so his diplomacyskills were subpar. And for such a tall guy, he was absolutely terrified ofbeing assassinated like his father, so he favored more autocratic reforms, andundid a lot of his liberal father’s work.

He wouldmarry a Danish princess who took on the name Maria Fyodorovna, who was relatedto ton of other European monarchs. They had a fairly happy marriage, and it’sbelieved Alexander III is the first tsar to not take a mistress (great Russianlove stories, the royal family had).

And now we’vereached the end of the line with his son, Nicholas II. Much like his father,Nicholas was not ready to become tsar. He even literally said “I’m not ready tobecome tsar”. Even so, a week after his father’s funeral, he married AlexandraFyodorovna, and was crowned.

People didn’tlove Alexandra. She was more than willing to convert to Orthodoxy, but sheshied away from most empress duties that involved public engagement. Alexandracame off as, frankly, a bitch to the Russian people, and pushed for an evenmore authoritarian rule than that of Alexander III. People also didn’t like herGerman background, and her relationship with Rasputin was iffy. No one knewwhat the deal was there.

Nicholas wasactually pretty devoted to Alexandra, and in being so, kind of hurt his ownimage. It’s easy to speculate that led to what happens next.

In 1917 Nicholaswas forced to abdicate, and his brother Mikhail was offered the throne, but herefused it. And there’s a pretty clear idea that Mikhail taking over would havebeen illegal, since the TsesarevichAlexei should have been next in line, as the tsar’s only son.

The familywas exiled to Siberia, then to the Ipatiev House, where they were shot in thebasement, which is a fabulously bloody story that I don’t have the stamina for.The bodies were burned and then soaked in acid, buried in an unmarked grave,and left undiscovered until 1979, but they were left until Communism had fallenin Russia.

Besides thetsar’s family, other extended members of the Romanov’s were executed in variousways. Others, like the Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna, were exiled, butallowed to live.

There were,of course, stories of children surviving (i.e. the famous Anna Anderson), butnone were ever confirmed.

As far as Iknow, the last remaining Romanov heir died in 2010, at 90-something

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

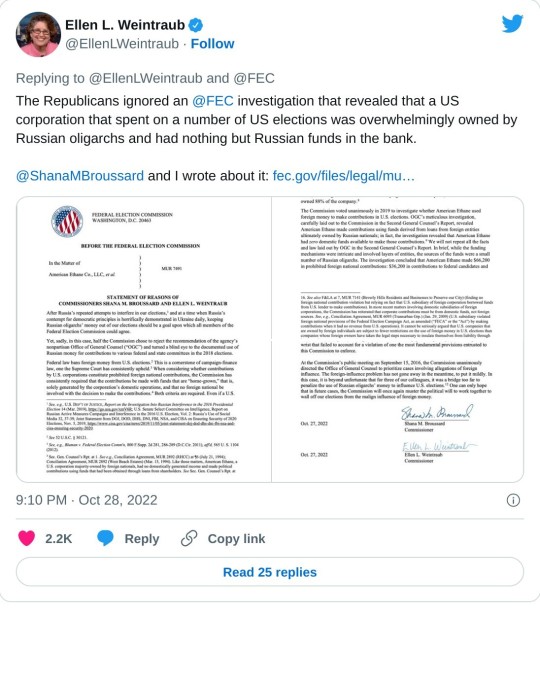

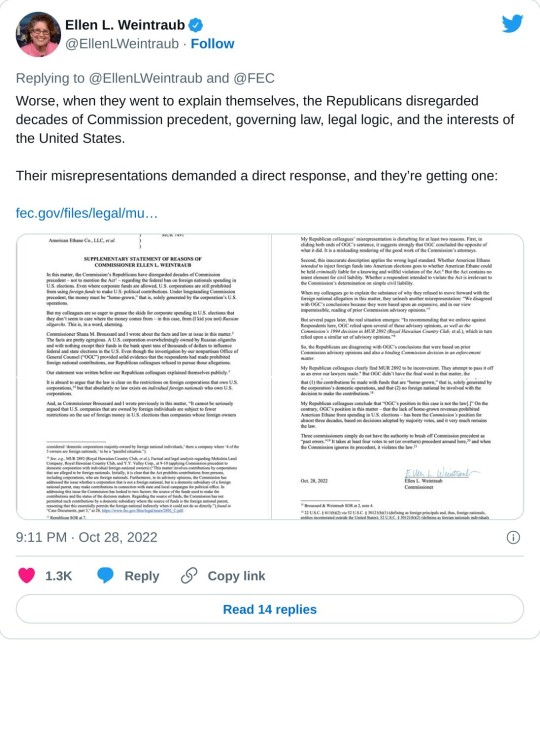

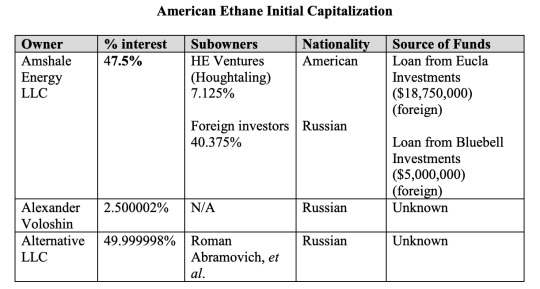

The Federal Election Commission recently let a US company that was quietly bankrolled by Russian oligarchs off with a slap on the wrist despite discovering that it had illegally funneled Russian funds to US political candidates in the 2018 midterm elections, two Democratic FEC commissioners said in a scathing statement issued Friday.

“Half the Commission chose to reject the recommendation of the agency’s nonpartisan Office of General Counsel and turned a blind eye to the documented use of Russian money for contributions to various federal and state committees in the 2018 elections,” wrote the two commissioners, Ellen Weintraub and Shana Broussard.

Anyone who follows campaign finance knows that the FEC has been toothless for years due to GOP commissioners’ opposition to any enforcement of laws designed to oversee money in politics. But Weintraub and Broussard suggest the agency hit a new low by letting the US firm, American Ethane, off with a deal in which it agreed to pay only a small civil fine.

Though based in Houston, Texas, and run by American CEO John Houghtaling, 88% of American Ethane was owned by three Russian nationals—Konstantin Nikolaev, Mikhail Yuriev, and Andrey Kunatbaev. The FEC report said that Nikolaev, an oligarch and Russian billionaire with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, is the controlling shareholder. Separately, Nikolaev also underwrote efforts by Maria Butina, a Russian gun rights activist, to cultivate ties with the National Rifle Association officials and with associates of Donald Trump around the time of the 2016 election. In 2018, Butina acknowledged acting as an unregistered Kremlin agent and pleaded guilty to participating in a conspiracy against the United States. She was sentenced to 18 months in prison but was deported six months later.

According to lobbying disclosures, the company was seeking help from US officials in its efforts to sell US ethane to China and, in 2018, had hired a US lobbying firm, Turnberry Solutions, with close ties to former Trump campaign chief Corey Lewandowski. A year later, Lewandowki officially joined Turnberry, after previously disputing his connections to the firm. Turnberry, which traded on ties to Trump, shut down in 2021, months after he left office.

The FEC investigation began after it received a complaint citing press reports on American Ethane’s ties to Nikolaev and its donations to lawmakers. Weintraub and Broussard noted that the FEC found that American Ethane “made contributions using funds derived from loans from foreign entities ultimately owned by Russian nationals.” Federal law bans foreign funds in US elections, as well as direct corporate donations to candidates. American Ethane seems to have done both. The FEC found that the company made more than $66,000 in donations using money it got from offshore firms in the form of loans. According to an FEC general counsel’s report released last year, the owners of the offshore firms included Alexander Voloshin, a Russian politician and former state power company official, and Roman Abramovich, an infamous Russian oligarch and former owner of the British football powerhouse Chelsea. The money the company used to dole out donations ultimately came from the oligarchs, the FEC said.

During its four-year investigation, the FEC found that the funds initially put up by Abromovich and other Russian nationals were then funneled to Republicans in Louisiana: Sens. John Kennedy and Bill Cassidy, a political action committee run by Kennedy, a leadership fund run by House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, a PAC backing Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, and the campaigns of Reps. Mike Johnson and Garrett Graves. Other contributions went to state lawmakers. The report didn’t explain why the company focused on Louisiana but the state is home to many natural gas firms, and its lawmakers advocate for the industry.

The lawmakers who received funds have not been accused of knowingly taking Russian money, though the final report from the initial investigation noted, “American Ethane attempted to make more political contributions, but those recipient committees never deposited American Ethane’s checks.”

American Ethane argued that the funds the company first received appeared as loan to the American corporation. Therefore, they claimed the donations it made were not foreign. The FEC rejected that argument. But it still recommended the firm only pay $9,500 as a civil penalty.

“The foreign-influence problem has not gone away in the meantime, to put it mildly,” Weintraub and Broussard wrote. “In this case, it is beyond unfortunate that for three of our colleagues, it was a bridge too far to penalize the use of Russian oligarchs’ money to influence U.S. elections.”

#us politics#news#mother jones#2022#federal election commission#russia#russian federation#russian oligarchs#2018 elections#Ellen Weintraub#Shana Broussard#Republicans#gop#conservatives#American Ethane#Maria Butina#valdimir putin#Konstantin Nikolaev#Mikhail Yuriev#Andrey Kunatbaev#Turnberry Solutions#Corey Lewandowski#Donald trump#sen. john kennedy#sen. bill cassidy#rep. Steve Scalise#Jeff Landry#rep. Garrett Graves#rep. Mike Johnson#campaign finance laws

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mikhail Khorobrit (1248)

Mikhail Iaroslavich Khorobrit (The Brave) (Russian: Мих��йл Ярославич Хоробрит) was Prince of Moscow (1246–1248) and Grand Prince of Vladimir in 1248. He was a younger brother of Aleksandr Nevsky and he and his son, Boris, are sometimes said to have been princes of Moscow before Daniil Aleksandrovich, although this is not always accepted. In 1248, he seized the town of Vladimir and expelled Grand Prince Sviatoslav Vsevolodovich, his uncle, who fled to Yuriev-Polsky. Mikhail was killed fighting the nephews of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas, Tautvilas and Gedivydas, at the Battle of Protva on 15 January 1248.

More details can be found in the directory Android, Windows

0 notes