#SSPE dangers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Call : +917997101303 | Whatsapp : https://wa.me/917997101505 | Website : https://fidicus.com

Precautions, neglect Complications SSPE, Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis | Treatment Cure Relief | Rare Orphan Unique Disease | Dr. Bharadwaz

Speciality Clinic

Fidicus Rare Disease

highest success with homeopathy

Any Disease | Any Patient | Any Stage

About Video : Diving into SSPE, let's navigate through essential precautions and prognosis means what happens when you neglect this disease. Explore crucial steps to safeguard against SSPE, understanding the disease's trajectory and potential outcomes. Gain insights into preventive measures, prognosis factors, and proactive approaches for managing this challenging condition. Empower yourself with knowledge for a better understanding of SSPE's journey.

#Rare Disease#Orphan Disease#Unique Disease#Homeopathy#Cure#Treatment#Prevent#Relieve#Alternative Therapy#Adjuvant Therapy#Alternative Medicine#Alternative System#prognosis#diagnosis and complications of measles#measles and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis#measles and pneumonia#measles and encephalitis#measles and sspe#measles and swelling of brain#wash hands frequently#cns infection#SSPE precautions#precautions for SSPE#SSPE dangers#SSPE complications#Youtube

0 notes

Text

25 children are dead in Samoa from measles, at least 1500 deaths in the Congo, more in Madagascar. These deaths could have been prevented, more are in critical condition and those that survived are in danger for the next 10 years of developing SSPE.

THIS is why I have no patience for anti-vaxxers. The lies they spew are KILLING children. There is a reason WHO declared them a top 10 world health threat.

If you are an anti-vaxxer reading this, fuck off with the anti-science, lying horse you rode in on you accomplices to manslaughter.

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

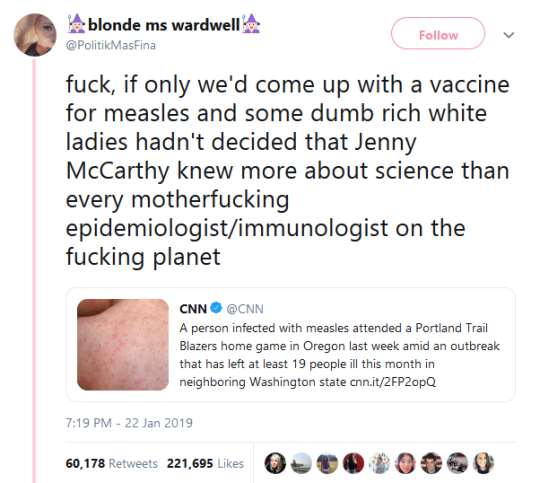

Reminder: The United States completely eliminated measles almost twenty years ago. Outbreaks occurred only “via travelers coming from countries where measles is still common.”

“The virus has spread among school-age children whose parents declined to give them the vaccine, which confers immunity to the disease. A vocal fringe of U.S. parents cite concerns the vaccine may cause autism, despite scientific studies that have debunked such claims. ... 72% of the people infected with measles were unvaccinated. Of the others, 10% had at one of the two recommended vaccine doses, while the status of the remaining 18% was unclear.”

Reminder: Measles is not just an uncomfortable rash.

“Measles can be dangerous, especially for babies and young children. From 2001-2013, 28% of children younger than 5 years old who had measles had to be treated in the hospital.”

Measles can lead to:

Pneumonia (a “serious lung infection”)

Deafness

Lifelong brain damage

And yes, even death (“Measles kills about 1 in 1,000 who get it”)

“Measles is highly contagious and not always a transient illness -- it can have serious complications and even prove fatal. ... These include pneumonia as well as encephalitis, which causes the brain to swell. A case in point is the 43-year-old Israeli flight attendant for El Al who remains in a coma after catching the measles and developing encephalitis. ... When children under age 2 get the measles, an inflammation of the brain called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) can develop five to 10 years later. ... SSPE can cause seizures, blindness, paralysis and eventually, a persistent vegetative state and death.”

#us#usa#measles#infectious diseases#children / youth issues#health news#health#children#vaccines#MMR#MMR vaccine#anti-vaxxers#science#anti-science#conspiracy theories

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Off-Switch for a Ticking Time-Bomb: The Importance of the Measles Vaccine

The pattern is clear: over the last decade or so vaccination uptake globally has dramatically declined, and cases of measles and other illnesses commonly vaccinated against during childhood has dramatically increased.

This is a pattern that is also being seen in the UK. A recent report by Unicef and the World Health Organization (WHO) found that between 2010 and 2017, 527,000 children in the UK who were eligible to receive their vaccinations were not vaccinated. This has led to spikes in cases of measles in certain parts of the country – ‘Public Health England (PHE) said there had been 47 cases across Greater Manchester in 2019, compared to only three cases in 2018 and seven in 2017’ (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-manchester-48040787). The issue has recently been described as ‘a ticking time-bomb’ by the NHS chief Simon Stevens: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-48039524.

The accepted cause for these patterns is growing concerns some parents have concerning vaccinations and the effects they have on their children. It’s worth saying at this point that I am about to start working as a doctor within the NHS and I passionately believe in the vital role vaccination plays in public health. Because of this, I have decided to make this short little piece to try and answer some of the most common questions and concerns some parents have regarding vaccines. These questions are the ones I have seen most commonly being asked during my clinical placements in hospitals and GP practices, as well as on the internet and social media. I have tried to reference all the answers to show that they’re not just my wild imaginings and are all backed up by thorough evidence and research.

If you’ve ever felt concerned or sceptical about vaccinations, if you have seen or read anti-vaccination literature in the past, or if you are just curious, please just give this a read and let me know what you think.

Do vaccinations even work?

Yes. Numerous studies by various organisations worldwide, including WHO, have shown that vaccinations are secondary only to clean water in reducing the burden of disease on a population (https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089/en/). As long as the uptake rate is high enough, vaccination can dramatically reduce the incidence of its target disease, and in some cases even eliminate it from the population. This occurs through an effect known as ‘herd immunity’ – this means as long as enough of the population take up the vaccine – around 90-95% for measles – so many people are immune to the virus that it can no longer survive in that community. This elimination of a disease has actually been achieved in some instances, such as the eradication of smallpox in 1980 through a vaccination programme. Local elimination of measles has also been seen in areas with high uptake of the measles vaccine e.g. in Finland. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089/en/

How do vaccines work?

To understand how vaccines work, its first best to get an idea of how our body fights an infection. When exposed to a bacteria or virus, our body can quickly become a battlefield. Our body puts up a whole host of defences to try and stop the bacteria or virus spreading throughout the body. Some of these defences include increasing body temperature to try and burn off the infection (this is why we get fevers) or even just trying to cough or sneeze up the bacteria or virus in snot or mucous.

Our soldiers in this battlefield are called white blood cells. A specific type of white blood cell called a B cell can learn to recognise certain shapes on the cell of the infecting organism that are unique to that bacteria or virus – just like people have their own distinctive looks and facial features that help you recognise them. Once it realizes this, the cell makes many clones of itself so that next time that same bacteria or virus attacks the body, it can quickly be recognised and all your body’s defences can attack and destroy it, usually before you even start to feel ill.

Vaccines work in the same way. Vaccines contains a little bit of this unique bacteria/virus shape and allows your body to see it, recognise it as an invader and then memorise it. This means that if your body ever gets infected with the real deal, your body will recognise it quickly and be able to destroy it before you even start to feel ill. Some vaccines contain just this little shape, while others contain dead or deactivated versions of the virus or bacteria which cannot cause true infection but still allow your body to learn its unique shape. The measles vaccine contains a weakened, also known as attenuated, form of the virus.

This video explains the process pretty well too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-muIoWofsCE

Isn’t measles just like a bad case of the flu? Does my child really need to be vaccinated?

Widespread vaccination programmes are still a relatively recent thing (the first vaccine against measles in the UK was introduced in 1968). Despite this, the programme has been so effective that measles became a forgotten disease that we didn’t see anymore and only the older generation could remember.

Public Health England

http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/measles

Measles is a lot worse than a bad case of the flu. Children who develop measles at first develop fever, greyish-white spots in the mouth and a distinctive red-brown rash that starts behind the ears before spreading to the rest of the body. Children are usually unable to get out of bed for around five days and can miss up to two weeks of school. The initial infection often also leads to complications such as further infections in the ear, lung or even the brain.

But beyond these usual cases, in a minority of children infected with measles, the disease can be fatal. It is thought that one out of every 5000 children infected with measles will die. The famous children’s author Roald Dahl’s daughter died of a complication of measles and he spent much of his life after her death campaigning and spreading the word about the importance of vaccination in the fight against measles and other infections. You can read his account of his daughter’s death and the effect it had on him here: http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/blogs/ojohn/how-dangerous-measles).

In a small number of cases, some children infected with measles go on to develop a condition called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). The children often don’t develop the condition until years after their initial measles infection. Its caused by the measles virus spreading to the brain, leading to destruction of the central nervous system, dementia, epilepsy and eventually death. You can watch a video on the effect SSPE has had on a family’s life here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aB8kGwKZiq0

If everyone else is vaccinated, does it really matter if my child doesn’t get the vaccine?

As explained earlier, eliminating a virus or bacteria from a community is dependant on the effect of herd immunity. For the measles virus, it has been calculated that around 90-95% uptake is needed to provide effective protection against the virus for the population. There are a number of children who, for many reasons, will not be able to receive the vaccine. These reasons include them being too young to receive the vaccine (the vaccine against measles is usually given at around 1 year of age) or if the child has other illnesses e.g. cancer, that mean its immune system is not able to mount an effective immune response to the vaccine.

This means that if healthy children are not vaccinated, they may carry the virus and spread it to children who are not able to receive the vaccine. If a healthy unvaccinated child gets infected with measles they will likely be able to fight off the infection themselves but may inadvertently spread it to children who are not strong enough to fight the infection. In these children, the risk of developing complications and severe infections is much more likely and so it is very important for all children who can be vaccinated to be vaccinated in order to protect everyone.

Don’t vaccinations cause autism?

No. This controversy was started after a paper was published in the medical journal the Lancet in 1998 claiming that there was a link between children who received the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and children who went on to develop developmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder. The claims made in the paper were quickly picked up by the national press and led to a widespread distrust of vaccinations that is still felt in some areas of the UK and the world today.

Due to the seriousness of the claims and the panic it caused, a vast amount of time and money went into research looking into the link. They all reached the same conclusion: there is no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. They also found that Andrew Wakefield’s study had been seriously flawed:

1) Wakefield selected patients that had already started to show signs of autism before his study began, meaning his study wouldn’t be a fair reflection on the effect of the MMR vaccine on the general population.

2) Wakefield falsified the information to suit the results he wanted to get e.g. one child in the study had already started to show some signs of autism before receiving his MMR vaccine (this was clearly stated in the child’s medical records), but in Wakefield’s report it stated that the first signs appeared months after the vaccination

3) Wakefield was being paid to conduct the research by lawyers representing parents who were against vaccines. This meant that he was set to gain financially if he could discredit the safety of vaccinations.

The man behind the now disgraced report linking the MMR vaccine to autism; Andrew Wakefield

For all these reasons, the Lancet retracted the paper and Andrew Wakefield was later found guilty of deliberate fraud and struck off from the medical register, although he still has a large following in some parts of the world, particularly in the anti-vaccination community. Due to the amount of research that went into investigating the link between the MMR vaccine and autism at the time, the fact that there is no link between the two is now one of the most well-proven things in modern medicine.

You can find more in-depth information on why Wakefield’s paper was fraudulent and unreliable here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136032/ and https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452. And more information on research into the link between the MMR vaccine and autism can be found at the bottom of this page ‘Is The Vaccine Safe?’: http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/mmr-vaccine

Could my child get ill from the vaccine?

Because a vaccine is trying to trick the body into thinking that there is an infection starting, the body can sometimes switch on all its defences after a vaccine e.g. fevers, runny noses. This occurs in around 1 in 10 children who receive the vaccine and normally wears off after 2-3 days. Another common side effect is redness and some pain and swelling around the site of the injection, which again quickly wears off.

In a small number of cases (1 in 1000), some children can develop fits or seizures following the vaccine. Although this is a serious side effect and will need medical attention, it is worth remembering that fits and seizures are far more common in child infected with the real measles virus.

Some parents also voice concerns regarding allergy to the measles vaccine, particularly regarding children with egg allergies. Although the measles virus strain used for the vaccine are grown on chick embryo cells there will only be tiny, if any, amounts of egg protein in the vaccine and not enough to cause an allergic reaction. Like all foods and medicines, there is a risk that a child could have an allergy to another of the ingredients of the vaccine leading to a serious allergic reaction called anaphylaxis. This kind of a reaction is extremely rare with the measles vaccine. However, this is why many healthcare professionals may want to observe the child for a few minutes following the vaccination to ensure the child doesn’t have a reaction. If a reaction does occur, the child can be quickly treated with adrenaline (the same stuff that’s used in EpiPens for people with other allergies).

If you have any concerns about your child following a vaccination, please contact your GP or other healthcare professional for more advice.

More information on the side effects of the MMR vaccine can be found at: http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/mmr-vaccine

Aren’t there lots of nasty chemicals in MMR vaccine?

As well as the active ingredients needed to trigger the immune response, the MMR vaccine also contain some other ingredients that help the vaccine work:

- Gelatine to act as a stabiliser (this is only in one form of the vaccine, a version not containing gelatine is also available)

- Sorbitol, mannitol and recombinant human serum albumin all act as stabilisers

- Polysorbate 80 is used as an emulsifier

- The vaccine may also contain traces of an antibiotic called neomycin, which is used during the manufacturing process to stop bacteria growing and contaminating the culture

None of these ingredients have been shown to be harmful to humans. You can find out more information on the ingredients of the MMR vaccine at: http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/mmr-vaccine

I hope you have found this piece interesting and I hope it has answered some questions you might have concerning the MMR vaccine. It is worth underlining that measles and the other infections protected against by vaccines are serious infections that are horrible to go through and can in a number of patients lead to serious complications and even death. Vaccination is vital in protecting both our healthy children and also those too young or too ill to receive the vaccination.

If you have any questions regarding the MMR vaccine or vaccines in general, please do not hesitate to contact your GP or other local healthcare professional.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Most of the time when people die or are injured from a vaccine, it’s due to an allergy. And most of the time that settlements are awarded, it’s due to something like the doctors knew that the child in question had a family history of allergy or adverse reaction to the vaccine components and/or was immunocompromised and did it anyway, so yes it was medical negligence. And that’s being extremely generous; most of the “vaccine injuries” people claim occur so rarely there is absolutely no way you can prove it was related to the vaccine, let alone caused by it. In the WHO fact sheet about measles vaccine risks, they go so far as to list 1-10 per MILLION doses, and even so, some of the supposed risks are so low that even at that rate, they find no association. (Those “risks” being things like autism, ibd, gbs, and sspe.) That’s less than one in a million chances, but your chances of getting complications from measles ranges from 1 in a thousand to 1 in 10.

Measles is not just rash and cough and fever. If an child gets measles, they could often get ear infections or diarrhea. And no, it’s not just malnourished people that die from diarrhea. You can die easily from dehydration, and diarrhea is a great way to get dehydrated. Especially if you’re a young child, which is why diarrhea in a child under 5 is supposed to send you straight to a doctor or even ER! Even my husband, a grown man who knew all about staying hydrated, ended up in the ER over what turned out to be flu-induced dehydration.

But let’s go on to some other complications that are more serious and shockingly common. Like pneumonia, or encephalitis, which happen at rates of 1/20 and 1/1000 respectively. Or death, which is also 1/1000. I’d much rather take a generally unproven 1/million risk of vaccine reaction than leaving my child or myself exposed to something that has a 1/20 chance of pneumonia (which could kill you), or a 1/1000 chance of dying.

But that’s just children. Rates of severe complications like encephalitis (and thus brain damage/death) and severe pneumonia or fever are WAY higher in adults over 20. Weird how a supposed childhood rash is actually most dangerous for grown people (and babies/the immunocompromised, of course).

Also, the flu generally doesn’t kill that many people, but the Spanish Flu certainly did. What’s to stop measles from mutating and becoming way worse unless we go ahead and eradicate it?

Even if we ignored all that, there’s the fact that measles doesn’t just cause primary illness, it destroys part of your immune system as a whole. Not in the way that the flu leaves your immune system weak, just thru stress, but as in it destroys your body’s ability to remember past invaders. Your immune responses more or less get reset. You may have been immune to something that you were vaccinated against or had even caught, like chicken pox or (heaven forbid) whooping cough, but once you catch measles, your immune system forgets it all! You not only are more likely to get secondary illnesses in the following weeks/months, like a skin infection from scratching the rash, you’re at risk for basically everything else all over again until you retrain your immune system. Because that lovely “just a rash” nuked your T-lymphocytes, which are the things responsible for programming your immune responses.

Basically it all boils down to: There’s a reason people spent the money and time to research the things we have vaccines against. It’s never “just a rash” or “just a cough.” Measles is the world’s most efficient and most contagious illness, even more than the killer Spanish Flu (approximately 5 to 6 times more contagious!), and it is so much more than just a rash.

VACCINATE YA KIDS FFS

327K notes

·

View notes

Text

7 Frequent Issues of the Measles

When many individuals hear the phrase "measles," they typically consider the preliminary adopted by a rash three to 5 days later. However there are additionally problems of measles that individuals want to concentrate on. "Measles can start out as a rash, but it can escalate very quickly to dangerous complications," stated Swapna Reddy, JD, MPH, a well being legislation and coverage professor at Arizona State College, in Phoenix. Kids youthful than 5 years of age and adults older than 20 years of age are most in danger from measles , studies the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention (CDC). However nobody is totally protected from problems. "We get concerned about very young babies because we can't vaccinate them. So of course we see the most complications in that age group," stated Dr. Sharon Nachman, chief of the division of pediatric infectious ailments at Stony Brook College Hospital, in Stony Brook, New York. "Having said that, if you get measles at any age, you can have complications such as measles pneumonia or measles encephalitis." This is an summary of the most typical and severe problems of measles.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is the most typical measles complication, occurring in about 1 in 12 individuals with measles.

Ear infections

Ear an infection is one other frequent complication of measles. About 1 in 14 individuals with measles will get an ear an infection. This happens primarily in youngsters. Ear infections aren't simply uncomfortable, however they'll additionally result in everlasting listening to loss.

Pneumonia

About 1 in 16 individuals with measles will develop pneumonia, both viral or bacterial. Pneumonia is the most typical reason behind measles-related loss of life in youngsters.

Encephalitis

Acute encephalitis, or swelling of the mind, happens in about 1 in 1,000 individuals with measles. Signs begin on common six days after the looks of the measles rash. These embrace fever, headache, stiff neck, drowsiness, vomiting, convulsions, and coma. A 43-year-old El Al Airways flight attendant just lately developed encephalitis after contracting measles. She's now in a coma and desires a respirator with a view to breathe. About 15 p.c of people that develop measles encephalitis will die. As much as one-quarter could have ongoing mind injury afterward.

Loss of life

The studies that in 2017, there have been 110,000 measles deaths around the globe. The danger is larger in younger youngsters and adults. The most typical reason behind measles-related loss of life youngsters is pneumonia. In adults, it is encephalitis. In america, about 1 in 500 individuals who had measles from 1985 by way of 1992 died. Though that is small in comparison with the remainder of the world, measles-related deaths are nonetheless a priority -- particularly with the within the nation in recent times. "The vast majority of deaths due to measles are happening outside the U.S.," stated Reddy. "But that picture is changing. And it's going in the opposite direction than we need to be headed."

Being pregnant problems

Ladies who develop measles whereas pregnant have a better threat of untimely labor, spontaneous abortion, or having a child with a low delivery weight.

Lengthy-term problems

One complication of measles can happen years after the preliminary sickness. Often called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), this degenerative illness impacts the central nervous system. Individuals develop signs on common seven years after having measles, though this ranges from one month to 27 years. Signs embrace problem considering, slurred speech, stumbling, falling, seizures, and ultimately loss of life. The CDC that four to 11 out of each 100,000 individuals who contracted measles in america from 1989 by way of 1991 have been susceptible to growing SSPE. The danger could also be larger for individuals who get measles earlier than 2 years of age. SSPE has been extraordinarily uncommon in america for the reason that early 1980s. However Nachman stated that as measles instances within the nation improve, we're more likely to see not less than one case of SSPE within the close to future.

Vaccination is the perfect safety

The success of the measles vaccination program led to the CDC declaring that measles was in 2000. New instances, although, are nonetheless being introduced into the nation by unvaccinated vacationers, each Individuals and overseas guests. Nachman stated to ensure that vaccination applications to proceed being profitable, misconceptions about vaccines should be addressed. One in all these is dad and mom' issues over the preservative . After 2001, all childhood vaccines not included this preservative. As well as, the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine by no means contained thimerosal. The CDC additionally that analysis would not present any hyperlink between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. Vaccination prevents youngsters from getting the measles rash, but additionally the problems. "Measles comes with consequences -- some happen soon and others come later," stated Nachman. "All of those can be avoided with vaccination." As well as, on account of "community immunity," this safety can lengthen to the unvaccinated. "There are children that are just not capable of being immunized for one reason or another. This may take the form of kids that are immunocompromised, for example," stated Matthew Speer, a college analysis affiliate on the School of Well being Options at Arizona State College. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

4 things everyone needs to know about measles published first on https://brightendentalhouston.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

4 things everyone needs to know about measles

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

4 things everyone needs to know about measles published first on https://drugaddictionsrehab.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Link

We are in the midst of a measles outbreak here in the US, with cases being reported in New York City, New York state, and Washington state. In 2018, preliminary numbers indicate that there were 372 cases of measles — more than triple the 120 cases in all of 2017 — and already 79 cases in the first month of 2019 alone. Here are four things that everyone needs to know about measles.

Measles is highly contagious

This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. A full 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to the virus will catch it. And if you think that just staying away from sick people will do the trick, think again. Not only are people with measles infectious for four days before they break out with the rash, the virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infectious person coughs or sneezes. Just imagine: if an infectious person sneezes in an elevator, everyone riding that elevator for the next two hours could be exposed.

It’s hard to know that a person has measles when they first get sick

The first symptoms of measles are a high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis), which could be confused with any number of other viruses, especially during cold and flu season. After two or three days people develop spots in the mouth called Koplik spots, but we don’t always go looking in our family members’ mouths. The characteristic rash develops three to five days after the symptoms begin, as flat red spots that start on the face at the hairline and spread downward all over the body. At that point you might realize that it isn’t a garden-variety virus — and at that point, the person would have been spreading germs for four days.

Measles can be dangerous

Most of the time, as with other childhood viruses, people weather it fine, but there can be complications. Children less than 5 years old and adults older than 20 are at highest risk of complications. Common and milder complications include diarrhea and ear infections (although the ear infections can lead to hearing loss), and one out of four will need to be hospitalized, but there also can be serious complications:

Five percent of people with measles get pneumonia. This is the most common cause of death from the illness.

One out of 1,000 get encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, that can lead to seizures, deafness, or even brain damage.

One to two out of 1,000 will die.

There is another possible complication that can occur seven to 10 years after infection, more commonly when people get the infection as infants. It’s called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE. While it is rare (four to 11 out of 100,000 infections), it is fatal.

Vaccination prevents measles

The measles vaccine, usually given as part of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, can make all the difference. One dose is 93% effective in preventing illness, and two doses gets that number up to 97%. In general the first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, but it can be given as early as 6 months if there is a risk of exposure (as an extra dose — it doesn’t count as the first of two doses and has to be given after 12 months), and the second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first.

The MMR is overall a very safe vaccine. Most side effects are mild, and it does not cause autism. Most children in the US are vaccinated, with 91% of 19-to-35 month-olds having at least one dose and about 94% of those entering kindergarten having two doses. To create “herd immunity” that helps protect those who can’t get the vaccine (such as young infants or those with weak immune systems), you need about 95% vaccination, so the 94% isn’t perfect — and in some states and communities, that number is even lower. Most of the outbreaks we have seen over the years have started in areas where there are high numbers of unvaccinated children.

If you have questions about measles or the measles vaccine, talk to your doctor. The most important thing is that we keep every child, every family, and every community safe.

Follow me on Twitter @drClaire

The post 4 things everyone needs to know about measles appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

from Harvard Health Blog http://bit.ly/2UHKOs6 Original Content By : http://bit.ly/1UayBFY

0 notes