#The Work Of Art In The Age Of Its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings On Media

Text

The Work Of Art In The Age Of Its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings On Media (2008)

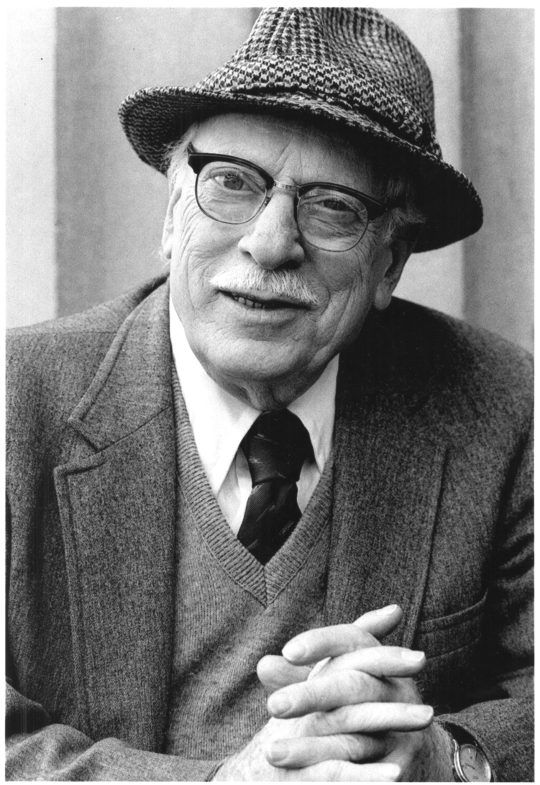

Walter Benjamin

Harvard University Press

#The Work Of Art In The Age Of Its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings On Media#Walter Benjamin#Harvard University Press#Started This Today

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you recommend any books or articles about the impacts of post-industrial capitalism and the commodification of literally everything? Its definitely something dark going on surrounding millennials and gen z with the impact of tik tok, IG, etc. Like idk how to describe it but it makes me sick. Everything feels like a constant state of anxiety and a bottomless pit of consumption. One of my professors even pointed out that younger generations are numbed by nihilism and a general feeling of hopelessness for the future. Its like a lot of us cope with our lack of control in the world by shallow attempts of aestheticizing/perfecting our lives. There is no room for imperfection, individuality, or even true love it seems its all so wrapped up in status. This is scary, thanks for talking about this.

I've just finished Capitalist Realism and highly suggest it- Most books about capitalism use tricky wording and Fisher really uses easy to understand language if you're new to it all. I've been meaning to read The Society of the Spectacle by Debord, also Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism by Fredric Jameson! Also have heard great things about Simulacra and Simulation by Baudrillard, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media by Benjamin. And you are so correct about everything, it's sounds so dreary and negative but it's true. I think living your life like, for example, a Moshfegh sad girl coquette character that's been popularised through Tik Tok and Instagram is just the continuation of consumption, loss of individuality and aesthetic nihilism that does absolutely nothing sadly.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Abeja Mariposa

@abejamariposa

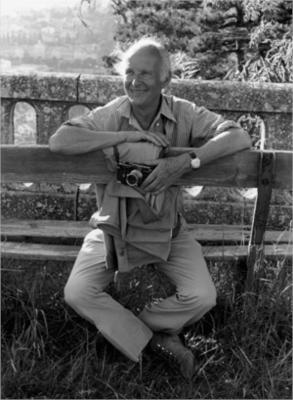

Abeja Mariposa is a Japanese street photographer and we have conducted this short interview where he tells us more about his work.

"In the fleeting expression of a human face, the aura beckons from early photographs for the last time. This is what gives them their melancholy and incomparable beauty"

Extract from"The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility" by Walter Benjamin

How did you start?

I am almost 50 years old and have never been particularly interested in taking photos in my entire life. But in early 2021, I took pictures of a glowing light bulb at home with my cheap smartphone just for fun. On low exposure, the round shape of the bulb stood out clearly in the dark and looked almost like a planet. It was so beautiful and interesting that I took pictures of all the bulbs in my house one after the other. As there were no bulbs left to photograph, I went outside and started taking pictures of the outside lights, road lights, street lights, traffic lights and so on. I was simply fascinated by the beauty of light. That was the beginning of my street photography.

At the end of October 2021, after ten months of practice with the smartphone camera, I finally bought a second-hand Fujifilm X-T30, which was my first real camera. It's been less than two years since I started taking photos, so when they contacted me for an interview, I was very surprised, like "Why a beginner like me?"

Who inspired you?

I have always been interested in any form of art, especially music and film. Music has a lot to do with visual images. I grew up in the MTV generation of the 80s and loved watching all those interesting and strange music videos. As for films, I love the old Hollywood musicals of the 1930s to mid-1950s, and filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch, Federico Fellini, Busby Berkeley and others. They may not have directly influenced my photographic work, but I suppose a variety of elements in them accumulate in memory and shape my work. If you've seen lots of classic film noir movies, it's only natural that you know how to take black and white night photographs without learning, for example.

Before I started taking pictures, I had been writing a blog called Stronger Than Paradise (https://strongerthanparadise.blog.fc2.com) for over ten years. Although it's basically a Sade (not Marquis de) fan blog, I wrote about various art-related topics. I think it shows my influences to some extent.

How would you define your style?

I have no idea. It's a free style. Actually, I haven't taken enough pictures to build my own style. Some photographers like to always shoot the same subject or the same kind of photos to clarify the style and get a following, but I don't like the way. I like to shoot various subjects in various ways, and I always want to take pictures that I've never taken before. I like it to remain eclectic rather than distinctive.

Do you have any projects you are working on?

Nothing special. Just take better pictures than yesterday and have fun - that's my project. Photography is a good hobby. The camera takes me to places I've never been. Taking pictures becomes the reason to go out. There are many beautiful things and moments in this world, even in everyday life. I would like to go to various places and find them for the rest of my life.

#abeja mariposa#photography#culture#art collective#photomagazine#art#london#bnwphotography#street photographer#streets storytelling#urban photography#urban exploration#japanese photography

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

7.2 Today's Art

While reading McLuhan, the most obvious connection/application to today’s art world and society was to Artificial Intelligence being used to create art. McLuhan argues that the medium is the limiting factor of any message; the message is solely inhibited by the capacity or function of the medium. When considering AI art, this is clear through the fact that there are some things that AI art cannot replicate like humans can. Many AI models struggle to depict human hands accurately. When viewing/consuming/using AI art, McLuhan would impress that we should consider the function of AI and how AI itself distorts the art it creates. This can include the various ethical concerns surrounding AI such as stealing art from other artists without credit, or falsifying information through generative images.

The biggest insight I have gained from reading the authors from this week is to truly not take anything at face value anymore in regards to art or creation. Benjamin’s concept of the Aura drives home the necessity for the encapsulation of the history and context of artworks and a desire to retain their objectivity and uniqueness. Combining this with McLuhan’s idea of the medium being the message, we should continuously be evaluating and re-evaluating the ways we are given information through art. Is the aura of a piece still intact, and if it isn’t, can it still function successfully as a medium? And, like McLuhan insinuates, we cannot go backwards or remove the effects of the new technological advancements happening every day; in order to keep up with them we must learn to see through the veneer of the message and into deep consideration of the medium.

References

Benjamin, W. (2008). The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, second version. In M. W. Jennings, B. Doherty, & T. Y. Levin (Eds.), The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media (E. Jephcott, R. Livingstone, H. Eiland, et al., Trans.). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

McLuhan, M. (1964). The medium is the message. In Understanding media: The extensions of man.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Analytical Application 1: Ideology and Culturalism

Aura :: The Greatest Gift

youtube

Definition: Aura, as conceptualized by Walter Benjamin, refers to the unique presence and authenticity associated with an original work of art. Benjamin writes that “[e]ven the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in… its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be,” (1) He argues that the aura is diminished in the age of mechanical reproduction, where artworks are mass-produced and disseminated, losing their singular authenticity and meaning (Ibid).

Analysis: Aside from perpetuating many other theories from Marx & Engles, Althusser, and Adorno & Horkheimer, this Christmas advertisement from Sainsbury highlights elements of mass mechanical reproduction that we can critique using Benjamin’s theory of aura. The story of this ad revolves around a presumably middle class worker trying to get his family the ‘greatest gift.’ He decides, after visiting his work’s toy factory, that the greatest gift that he can give is himself, consequently mass produces toy ‘clones’ of himself to do his work for him so that he can spend time with his family. However, applying Benjamin’s theory of mechanical reproduction, the ‘aura’ of the toy clones (and by association, the aura of the self) are lost as they are mass produced. They are completing simple tasks like attending meetings, pressing buttons on a keyboard, and taping boxes. This brings up the question; why is a human necessary for carrying out these tasks if a simple, mechanically reproduced toy can do the same thing? What implications does this have for the aura of a person themself if they are reduced to doing these tasks every day? The montage also shows the character’s coworkers being unfazed by the toys taking his place, alluding to the normalization of mass mechanical reproduction in our workplaces and homes, going so far as to replace a person’s presence. This analysis brings up another interesting point about Benjamin’s theory of ‘aura’ : has the demand for aura and authenticity been replaced? If so, by what?

Culture Industry :: It’s a Tide Ad

youtube

Definition: The culture industry, as described by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, refers to the mass production of standardized cultural products that serve capitalist interests. Adorno and Horkheimer explain that the “present technology of the culture industry confines itself to standardization and mass production,” (2) leading to products that serve the ruling ideas. These products, including advertisements, films, and music, are designed to promote conformity and perpetuate false consciousness among the masses.

Analysis: The Tide Super Bowl Commercial epitomizes the culture industry's influence on contemporary advertising. Its polished production value, use of celebrity endorsement, and broad appeal to mass audiences reflect the standardized and commodified nature of cultural products in capitalist societies. The advertisement employs familiar advertising tropes and product placements to create a sense of familiarity and conformity, aligning Tide detergent with various scenarios and stereotypes that resonate with societal norms. It also employs a sense of false consciousness by parodying these common tropes seen in ads for specific products, alluding to the idea that Tide is aware of these tropes and their effects (perhaps even promoting false consciousness). However, through these tactics, the ad reinforces capitalist consumerist values by directly associating Tide detergent with themes of cleanliness, success, and social acceptance. It even uses a counterexample of ‘dirtiness’ as a comedic character to further push conformity, forcing the association between cleanliness, social acceptance, and Tide. By presenting Tide as an essential part of everyday life (and an essential part of every other ad we see on TV), the ad promotes ruling ideas and values, encouraging consumers to align their purchasing decisions with the dominant ideology of consumer capitalism. Overall, the Tide Super Bowl Commercial exemplifies how the culture industry shapes advertising content to promote conformity and perpetuate capitalist values among mass audiences.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ideological State Apparatuses :: Thank You Mama

youtube

Definition: Ideological State Apparatuses, according to Althusser, are institutions that propagate ideology and shape individuals' beliefs and values to support the existing social order. Althusser highlights that these institutions are part of a “private domain” (3) which function by, well, “ideology,” (Ibid), or implicit coercion and persuasion rather than direct force in comparison to the RSA. Some examples of these institutions are advertising, family, and education (4).

Analysis: The P&G Thank You Mama advertisement serves as a prime example of how ideological state apparatuses operate within the realm of advertising. It utilizes ruling ideologies present in the Ideological State Apparatus to construct the ‘mother’ as a specific character playing a particular role in one’s life. Through its portrayal of maternal sacrifice and familial love, the ad constructs a narrative that reinforces dominant ideologies surrounding motherhood and family dynamics. By depicting mothers as selfless figures who are instrumental in shaping their children's success, the advertisement perpetuates societal norms and values related to gender roles and familial responsibilities. Furthermore, by associating P&G products with this narrative of familial love and support, the ad effectively aligns consumer behavior with these entrenched ideologies. The advertisement thus functions as a tool of ideological reinforcement, subtly influencing viewers to internalize and conform to societal expectations surrounding motherhood and family life (while consuming P&G products, of course). In doing so, the P&G Thank You Mama advertisement demonstrates the power of ideological state apparatuses in shaping cultural narratives, such as the role of the mother, at the same time as influencing consumer behavior. Along with all of these values, the advertisement also defines ‘success’ in a very particular way, associating it with athletic achievement that is recognized by the ruling class. While implying that these athletic achievements wouldn’t have been possible without the mother playing their role, it also aligns the viewer within the status quo of the ISA, associating specific achievements with true success.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ruling Class :: Alexa Loses Her Voice

youtube

Definition: The term 'ruling class' refers to the socio-economic elite that holds significant power and influence within a society's power structure. Rooted in Marxist theory, this concept describes how a small minority of people control the means of production and wealth, as well as conceptualizing and distributing the “ruling ideas,” (5). This elite group shapes societal norms, values, and power dynamics to serve its own interests, making up the “ruling material force of society at the same time as its ruling intellectual force,” (Ibid).

Analysis: In the Amazon Super Bowl LII commercial "Alexa Loses Her Voice," the concept of the ruling class is evident through the portrayal of Amazon as the authoritative provider of technological solutions and convenience in everyday life. The commercial begins with a fictional scenario of Alexa, the voice-activated assistant, losing her voice, leading to chaos as Amazon implements an interim solution: using celebrities as the new Alexa voice. Throughout the commercial, Amazon presents itself and its products as the dominant and indispensable providers of solutions and convenience in daily life while showing their priority for the customer. This advertisement features celebrity cameos from prominent figures like Gordon Ramsay, Cardi B, and Anthony Hopkins, who take Alexa’s place. By doing so, Amazon aligns itself with cultural authority and celebrity endorsement, reinforcing its position as a leader in the tech industry as well as being relevant with celebrities, who are all notable members of the ruling class. Secondly, the commercial highlights the versatility and integration of Amazon's products and services into various aspects of daily life. From controlling smart home devices to ordering products online, Amazon presents itself as the go-to solution for consumers' needs, further solidifying its dominant position in the marketplace. Additionally, the commercial subtly promotes Amazon's corporate values of innovation and customer-centricity, portraying the company as responsive and adaptable to unexpected challenges. By showcasing Amazon's ability to quickly address the issue of Alexa losing her voice with innovative solutions like celebrity replacements and product updates, the commercial reinforces the perception of Amazon as a forward-thinking and customer-focused company. Amazon also highlights Jeff Bezos’ concern for his customers and willingness to find an immediate solution (yeah, as if CEOs are the ones doing any troubleshooting in a big corporation like Amazon). This advertisement further cements Amazon’s ruling position in society, aligning the use of their products with the status quo.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Oppositional Code :: Iceland’s Banned TV Christmas Advert…Say Hello to Rang-tan…

youtube

Definition: Oppositional code can be defined as a form of interpretation or resistance within cultural texts, where individuals decode (or encode) meanings that challenge or subvert dominant ideologies or social norms. Stuart Hall gives an explain of an oppositional reading, where a “viewer listens to a debate on the need to limit wages but ‘reads’ every mention of the ‘national interest’ as ‘class interest’,” (6). This form of encoding and decoding allows individuals to resist hegemonic messages and assert alternative perspectives, leading to social critique, activism, or cultural transformation.

Analysis: In Iceland's banned Christmas Advertisement about Rang-Tan, oppositional code is utilized through the advertisement's critique of corporate-driven consumerism and environmental degradation. The advertisement portrays the story of Rang-Tan, an orangutan displaced from its habitat due to deforestation caused by palm oil production. Through emotive animated visuals and parallels to children’s storytelling and nursery rhymes, the advertisement challenges dominant narratives promoted by corporations and governments regarding environmental sustainability and corporate responsibility. Rather than promoting a product or brand, the advertisement focuses on raising awareness about the detrimental impact of palm oil production on wildlife and ecosystems. By highlighting the plight of Rang-Tan and the destruction of its habitat, the advertisement encourages viewers to question and challenge the practices of multinational corporations involved in palm oil production, encoding an uncommon anti-establishmentarian message. Furthermore, the ad employs a style of children’s animation and storytelling – almost like a nursery rhyme – to evoke empathy and emotional engagement from viewers, paralleling the cartoony visuals with real footage of deforestation. Through the use of vivid imagery and a poignant narrative, the advertisement encourages viewers to empathize with Rang-Tan and recognize the broader implications of environmental destruction caused by corporate greed. This banned Christmas advertisement serves as a powerful example of oppositional code being used in advertising. By subverting traditional advertising and storytelling conventions and promoting a message of environmental activism and social responsibility, the ad encourages viewers to challenge dominant ideologies and consider alternative perspectives on issues such as consumerism, environmental sustainability, and corporate accountability.

(1) Benjamin, Walter. 2009. “THE WORK OF ART IN THE AGE OF MECHANICAL REPRODUCTION.” In FILM THEORY AND CRITICISM Introductory Readings, 667. N.p.: Oxford University Press.

(2) Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Essay. In Dialectic of Enlightenment Philosophical Fragments, 95. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2002.

(3) Althusser, Louis. 2006. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation).” In The Anthropology of the State, 93. N.p.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

(4) Althusser, 92.

(5) Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 2010. “The Ruling Class And The Ruling Ideas.” In The German Ideology, 59. Vol. 5. N.p.: Lawrence & Wishart.

(6) Hall, Stuart. “Encoding, Decoding.” Essay. In The Cultural Studies Reader, 2nd ed., 517. Routledge, 2001.

0 notes

Text

The robot uprising and the end of the publishing world!

New Post has been published on https://kellshaw.com/the-robot-uprising-and-the-end-of-the-publishing/

The robot uprising and the end of the publishing world!

New Post has been published on https://kellshaw.com/the-robot-uprising-and-the-end-of-the-publishing-world/

The robot uprising and the end of the publishing world!

I can’t remember the exact title, but there’s an episode of Doctor Who where Tom Baker’s Doctor, and Romana are discussing life on Gallifrey, their home planet. The Doctor likes painting, but Romana thinks that’s archaic, as in her mind, computers do art. And while that was science fiction in the 1970s, today we’ve got AI tools that do art, and writing!

Every author business podcast I’ve listened to recently, and a lot of book-ish social media groups, are furiously discussing the impact of modern AI tools on publishing. There’s a mix of speculation, gossip and fearmongering.

Publishers with low-effort, AI-churned out bookswill swamp the market place! No one will touch self-published books again!

Readers won’t love us writers anymore as they can walk up to a computer, enter some prompts, and receive a perfectly tailored story to their tastes and preferences.

Canny publishers will use AI to increase their output and draw readers’ attention away from my stuff!

There are arguments on both sides. A lot of this appears to be FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) – the fear that the AI assisted texts will make certain writers more productive and take the readers away from discovering other writers! I don’t think it quite works like that. Sure, I’d love it if my favorite authors were more productive, but I’ve also stopped reading a series where the latest volume loses that spark and feels ‘churned out’. And even if everyone flocks to mass-produced texts, there will still be people who prefer hand-crafted stories. Maybe it will become like craft beer—there’ll be always an audience for those who want the more interesting beverages on the side.

What makes a good story? Intriguing characters, pacing, the ability to evoke emotion, perhaps. How do you bottle this and create a reliable, reproducible formula for making engaging stories consistently? People have been to figure this out for years. There’s so many courses out there that tell writers about how to write unputdownable stories, or what the best formulas. I’ve found some stuff useful (structuring and pacing techniques) and others less so.

There’s also been heartwarming stories of people with disabilities who can now express themselves better using AI technology. People with language issues or Long COVID brain fog can now complete stories with AI assistance. This is how I’d like it to be used. I’ve got some issues myself, which makes it hard for me to engage in social media. I have trouble writing random social media posts about blah life stuff without wanting to sit and think deeply about out it for ages, but if I bothered, I could go to the ChatGPT and have it write my social updates for me!

I haven’t mucked around with AI yet. Actually, I tell a lie—I use souped-up grammar checker Pro-Writing Aid to clear up my text. I’m a messy first drafter with lots of dropped words, speling errors that are fixed down the pipeline. I use some of its suggestions, but not all. Lately it’s got this AI feature that rephrases sentences. Some of it sounds better, some of it’s bland. Mostly I ignore it. But the tool is there as an option. Anyway, more options are good.

At this stage, I’m not going to engage AI (apart from PWA’s grammar/reporting checks). I’m still working on my craft, trying to capture that magic of making a great story, or at least, improve of what I’ve done in the past. For example, when I wrote Final Night, it was the best thing I’d written and completed, and now I’m going to improve on that with the next book. When I think I’ve gotten my craft to a certain level, I might check out AI tools more deeply, but for now it’s fingers to keyboard.

0 notes

Text

Notes:

Walter Benjamin —The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

Reproduction over the ages; Pg 3-4

In principle, the work of art has always been reproduc-ible. What man has made, man has always been able to make again. Such copying was also done by pupils as an artistic exercise, by masters in order to give works wider circulation, ultimately by anyone seeking to make money. Technological reproduction of the work of art is something else, something that has been practised intermittently throughout history, at widely separated intervals though with growing intensity. The Greeks had only two processes for reproducing works of art technologically: casting and embossing. Bronzes, terra-cottas and coins were the only artworks that they were able to manufacture in large numbers. All the rest were unique and not capable of being reproduced by technological means. It was wood engraving that made graphic art technologically reproducible for the first time; drawings could be reproduced long before printing did the same for the written word. The huge changes that printing (the technological reproducibility of writing) brought about in literature are well known. However, of the Phenomenon that we are considering on the scale of history here they are merely a particular instance - though of course a particularly important one.

Ownership & Environment Context: Pg 5

Even with the most perfect reproduction, one thing stands out: the here and now of the work of art - its unique existence in the place where it is at this moment. But it is on that unique existence and on nothing else that the history has been played out to which during the course of its being it has been subject. That includes not only the changes it has undergone in its physical structure over the course of time; it also includes the fluctuating conditions of ownership through which it may have passed.

Reproduction - Inserting New Idea (V): Pg11

Paying proper attention to these circumstances is indispensable for a view of art that has to do with the work of art in an age when it can be reproduced by technological means. The reason is that they herald what is here the crucial insight: its being reproducible by technological means frees the work of art, for the first time in history, from its existence as a parasite upon ritual. The reproduced work of art is to an ever-increas. ing extent the reproduction of a work of art designed for reproducibility.? From a photographic plate, for instance, many prints can be made; the question of the genuine print has no meaning. However, the instant the criterion of genuineness in art production failed, the entire social function of art underwent an upheaval. Rather than being underpinned by ritual, it came to be underpinned by a different practice:

politics.

Cultivar Collecter vs Display Value - Pg 12-13 [ Display > Ritual ]

Works of art are received and appreciated with different points of emphasis, two of which stand out as being poles of each other. In one case the emphasis is on the work's cultic value; in the other, on its display value.%, Artistic production begins with images that serve cultic purposes. With such images, presumably, their presence is more important than the fact that they are seen. The elk depicted by the Stone Age man on the walls of his cave is an instrument of magic. Yes, he shows it to his fellows, but it is chiefly targeted at spirits. Today this cultic value as such seems almost to insist that the work fart be kept concealed: certain god statues are accessible only to the priest in the cella, certain Madonna images remain veiled almost throughout the year, certain carvings on medieval cathedrals cannot be seen by the spectator at ground level. As individual instances of artistic production become emancipated from the context of religious ritual, opportunities for displaying the products increase. The ‘displayability' of a portrait bust, which is capable of being dispatched hither and thither, exceeds that of a god statue, whose fixed place is inside the temple. The displayability of the panel painting is greater than that of the mosaic or fresco that preceded it. And if a setting of the mass is not inherently any less displayable than a symphony, nevertheless the symphony emerged at the point in time when it looked like becoming more so than the mass.

With the various methods of reproducing the work of art by technological means, this displayability increases so enormously that the quantitative shift between its two poles switches, as in primeval times, to become a qualitative change of nature. In primeval times, because of the absolute weight placed on its cultic value, the work of art became primarily an instrument of magic that was only subsequently, one might say, acknowledged to be a work of art. Today, in the same way, because of the absolute weight placed on its display value, the work of art is becoming an image with entirely new functions, of which the one we are aware of, namely the artistic function, stands out as one that may subsequently be deemed incidental. 10 This much is certain, that currently photography and its issue, film, provide the most practical implementation of this discovery.

Distraction vs Immersion — Pg 33

Clearly, this is at bottom the old charge that the masses are looking for distraction whereas art calls for immersion on the viewer's part. It is a platitude. Which leaves only the question: does this furnish an angle from which to study film? Here we need to take a closer look. Distraction and immersion constitute opposites, enabling us to say this:

The person who stands in contemplation before a work of art immerses himself in it; he enters that work - as legend tells us happened to a Chinese painter on once catching sight of his finished painting. The distracted mass, on the other hand, absorbs the work of art into itself. Buildings, most obviously. Architecture has always provided the prototype of a work of art that is received in a state of distraction and by the collective. The laws governing its reception have most to tell us.

Futurists view on War + Aesthetics - Pg 37

In Marinetti's Manifesto Concerning the Ethiopian Colonial War we read: 'For twenty-seven years we Futurists have been objecting to the way war is described as anti-aesthetic [ ... J. Accordingly, we state: [... ] War is beautiful because thanks to gas masks, terror-inducing megaphones, flame-throwers, and small tanks man's dominion over the subiect machine is proven. War is beautiful because it ushers in the dreamt-of metallization of the human body. War is beautiful because it enriches a meadow in bloom by adding the fiery orchids of machine-guns. War is beautiful because it combines rifle-fire, barrages of bullets, lulls in the firing, and the scents and smells of putrescence into a symphony. War is beautiful because it creates fresh architectures such as those of the large tank, geometrical flying formations, spirals of smoke rising from burning villages, and much else besides [ . . . J. Writers and artists of Futurism [ ... J, remember these principles of an aesthetics of war in order that your struggles to find a new kind of poetry and a new kind of sculpture [ . .. ] may be illuminated thereby!'

Following reading Walter Banjaming and taking notes I had understood the importance and evolution of art reproductions and their place within society. The difference between distraction and immersion of ideas and the potential reproductions have for inserting a new idea into the social conversation and structure. Looking at the history of reproductions from the Greeks to the present day I was able to understand the importance the work had on keeping knowledge and ideas alive. Aswell as to democratise the ideas to the public making them more accessible and dethroning it’s ‘cultic’ value. This closely relates to the work of Virgil that used a Pyrex shirt to bring Caravaggio’s work to young audiences - introducing them to the renaissance, the artists work and provoke them to question why the art is present and the meaning of message it has for our day and age today.

This book had a lot of great quotes and ideas which help give my essay validity and can cross reference practitioners that do reproductions and insert ideas into different mediums. Bringing fourth ideas and reincarnating the ideologies into new mediums and technologies.

0 notes

Text

Star Wars Alien Species - Mon Calamari

The Mon Calamari share their Outer Rim homeworld, the watery world of Mon Cala, with the aquatic Quarren.

The Mon Calamari had developed a very advanced and civilized culture. Art, music, literature, and science showed a creativity surpassed by few in the galaxy. An example of the art the Mon Cal used was the Squid Lake Ballet. The Squid Lake, was a performance of Mon Calamari Ballet, played at the Galaxies Opera House on Coruscant.

Mon Calamari literature depicted stars as islands in a galactic sea. This showed a passionate longing to explore space and discover other civilizations. In terms of temperament, they were both soft spoken and gentle. They were extremely tempered to the point that they were slow to anger and had the remarkable ability to maintain their concentration without being distracted by emotional responses. Other notable personality traits included being inquisitive and creative as well as being quiet. In addition, they were known for a near-legendary quality of being both determined and dedicated. This meant that once a Mon Calamari decided on a course of action, they were not easily swayed from that decision. As they were idealistic and daring, they often fixated themselves on causes that seemed hopeless or lost from the start. As such, they had a great deal of enthusiasm and spirit which was often masked by their quiet, orderly exterior. Ultimately, a Mon Calamari often attempted to demonstrate that even dreamers and thinkers were capable of daring and bravery when the need arose. This meant that they often thought of the needs of the society and believed in performing the greater good to the point that they placed it above the good of the individual.

They had developed a reputation for being one of the most skilled starship designers in the galaxy. This partly stemmed from the fact that they saw everything as a work of art rather than being a simple tool or weapon. Their technology was notable for being unique, yet comparable to that of the other inhabitants of the galaxy. While their starships were significantly different from those of other races, they were in fact more efficient in design. However, such vessels tended to be extremely difficult to construct. The mathematically-minded Givin could not stand the Mon Calamari spaceships, as they were too organic and not geometric enough.

The Mon Calamari were a bipedal, amphibious species with high-domed heads, webbed hands and large, goggle-like eyes. In addition to being webbed, the Mon Calamari hand presented three suction-cup like holes on its palm, and featured five claw-tipped fingers: one opposable thumb, two long middle fingers, and two very short outer fingers. Although they were shaped like flippers, their feet could nevertheless fit into boots designed for humanoid feet. The females were distinguished from the males by their more prominent chest areas. The individuals that hailed from the colder polar extremes of their planet were noticeably less colorful than those who came from the tropical zones.

The Mon Calamari were vigorous swimmers and were capable of living underwater for long periods. The Mon Calamari spawned many offspring. For example, Raddus's grandchildren numbered in the dozens. However, because not all spawns were expected to come of age, the Mon Calamari felt loss less keenly than humans, who reproduced comparatively rarely and fewer.

A typical Mon Calamari stands at 1.8 meters or 5.9 feet tall and weighs 72 kilograms or 159 pounds.

Mon Calamari age at the following stages:

1 - 11 Child

12 - 16 Young Adult

17 - 40 Adult

41 - 57 Middle Age

58 - 79 Old

Examples of Names: Ackbar, Bant, Cilhal, Ibtisam, Jesmin, Oro, Perit, Rekara.

Languages: The Mon Calamari can speak, read, and write both Mon Calamarian and Basic. Most tend to also learn Quarrenese as well.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portraiture Through The Ages

In the 1940′s, camera technology wasn't as advanced as it is to this date, however within this time period, camera technology was considered the most advanced of its time period.

Beginning with the lowest of the low, we have the Kodak Brownie Flash Six-20...

The brownie box, being sold at $6.00 which was introduced in July 1946, is made from a metal box body, with a strange shape. It features an optical direct vision finder, a built-in closeup lens, and time exposure capability. It also accepts a cumbersome flashgun.

The Brownie Flash Six-20 camera was quite a popular camera in its time because of it's indestructibility, taking the place of the modern-day compact or cell phone camera in terms of market penetration.

This camera now sells for around $20-$30.

Up from this, we have the cheap folding cameras like the Agfa Isolette/Ansco Speedex.

There are two models of the Agfa Isolette, The early model, produced before and during WW2 and the later, produced after WW2. This camera, made by Agfa Kamerawerk AG, Munich, Germany, was named the ‘solders camera’ or ‘Soldatenkamera’. There were many different lens/shutter combinations to this camera, making it impressive in its time period.

The late model was made from 1946 till 1950 with the name writing as Jsolette or Isolette. The camera offered many different lens/shutter combinations, like f/4.5 Agnar, Apotar or Solinar lenses and Prontor, Prontor-S or Compur-Rapidshutters.

This camera costed around $15 back then, but are now sold for around $100-$500.

The Ansco Speedex camera was introduced in early 1940. The camera is labeled on the front as a Agfa B2 Speedex with a 85mm f/4.5 lens. It was actually made in Binghamton, NY when Ansco and Agfa merged. There are no interlock which prevents double exposures.

It is unknown its original price, but it is however sold for around $30-$70 modern day.

We next have the next technological progression, the high-end folding cameras. Equipped with the occasional rangefinder, these devices were even more expensive but were equipped with advanced lenses and shutters. The Kodak monitor 620, is a prime example of these types of cameras.

This camera was introduced between 1939 and 1948, originally sold for $48.50, now selling for around the same price. The camera has advanced features such as an automatic frame counter, double exposure prevention, an uncoupled depth of field scale, and dual viewfinders. This camera was extremely well produced and still is capable of capturing amazing images.

The Leica and their various camera models had produced photojournalism cameras for the international market since the early 1930′s and showed to be productive and effective on the market.

The Leicia IIIc was introduced 1940–1951. This was and still is a very valuable camera model, selling now for around $700-$1000, It was said to have took up 5% of the professional photography market.

Perhaps the most recognisable and famous most used camera of that time was the press cameras, the huge boxy cameras with the wireframe finders and flashbulbs.

These camera targeted 90% of the newspaper photography market 9 out of ten photographers who worked for news agencies chose Graflex models, one of the most popular brands of that time along side Busch (as shown in this image).

These were sold roughly for $3000 alongside with accessories and other gear. These cameras were the best of the best with the manufacturers pulling out all the stops to produce solid press cameras.

This is an iconic image taken on a Graflex by Joe Rosenthal.

Photographers in the 1940′s

Carl Mydans prepared himself from an early age for his lifelong involvement with journalism. Between 1940 and 1944, Mydans and his wife Shelley Mydans were in Asia, first covering Chungking in its stand against the Japanese bombings, then in Burma, Malaya and the Philippines. While in the Philippines they were both captured by the Japanese and imprisoned for 21 months. This, however, did not deter Mydans, as he went on to photograph many more wartime situations after his release. Mydans recorded photographic images of life and death throughout Europe and Asia during WW2 travelling over 45,000 miles.

General Douglas MacArthur Landing at Luzon, Philippines, 1945. ‘Blue Beach’, Dagupan, Island of Luzon, Lingayen Gulf, Philippines.

Casualties of a mass-panic during a Japanese air raid in Chongqing in 1941.

Joe Rosenthal spanned more than 50 years, he is best known for a single image: Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

The photograph of six men on a tiny island in the Pacific was immediately a symbol of victory and heroism, and became one of the most famous, most reproduced and even most controversial photographs of all time.

Flag Raising on Iwo Jima, 1945.

U.S. Marines of the 28th Regiment, fifth division, cheer and hold up their rifles after raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, a volcanic Japanese island, on Feb. 23, 1945 during WW2.

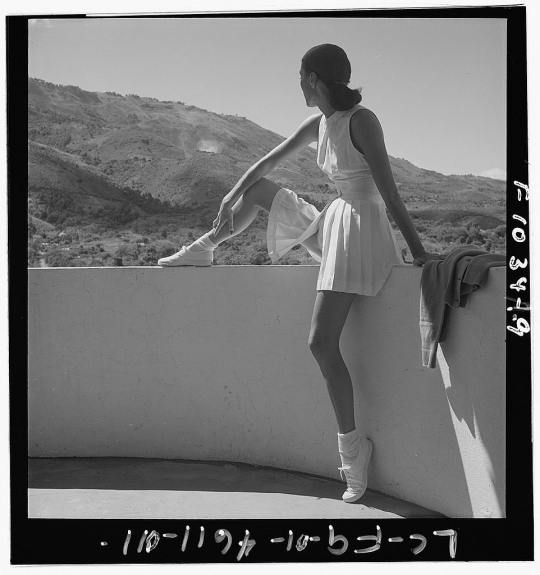

Toni Frissell trained as an actress and worked in advertising before devoting herself to photography.

Frissell had a major contribution to fashion photography in the 1940′s.

Woman wearing tennis outfit, seated on wall. Toni Frissell. 1947 Febuary.

Eleanor Roosevelt talking with woman machinist during her goodwill tour of Great Britain. Toni Frissell. 1942 November.

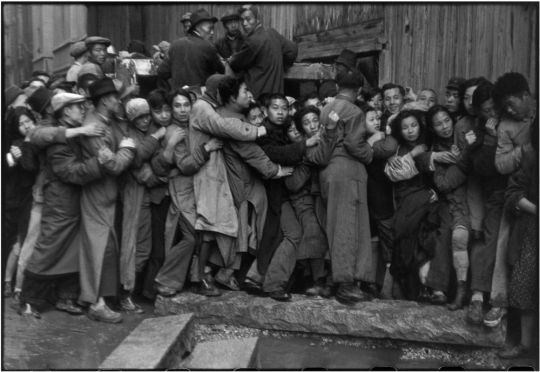

Henri Cartier-Bresson is a French photographer, a well-known figure in the history of photography during WW2. His work of spontaneous photographs helped establish photojournalism as an art form.

He was imprisoned by the Germans in 1940 during the Battle of France and spent 35 months subjected to forced labour in prisoner-of-war camps until, after several failed attempts, he escaped in 1943.

Germany, WW2, Henri Cartier-Bresson 1945.

Crowd waiting outside a bank to purchase gold during the last days of the Kuomintang, Shanghai, China, December 1948.

A fair amount of photographers during the 1940 period relied on documentary styled images, documenting the drastic happenings of that period of time, until In the period after WW2, as the United States entered a period of domestic peace and prosperity, many photographers there moved away from documentary style photography and focused instead mostly on the intrinsic qualities of photography.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Todd Hido’s first monograph, House Hunting, was published in 2001. A second similar book called Outskirts was published the following year. Most of the photographs in these first efforts are pictures of ordinary houses taken at night on the streets of economically struggling towns in Hido’s home state of Ohio, towns that were in the past the backbone of America’s industrial base. They were towns populated by factory workers who were said to embody the American dream of self-sufficiency and ownership for ordinary families leading ordinary lives but infused with hope and confidence in the future. As America’s industry has migrated overseas, a gnawing sense of loss and disillusion has enveloped homes like those in Hido’s pictures, but the physical structures that provided empirical confirmation of America’s idealism – single-family homes surrounded by picket fences on suburban streets – these structures remain, raising persistent and unsettling questions concerning the real nature of our country, its history and its future.

According to interviews, Hido’s procedure in making these pictures was straight-forward. He would drive around suburban neighborhoods in the dead of night, pull over, take the picture (in analog format using natural light) and drive away. Usually the house is dark except for light emanating from a single window. Occasionally the police were called, but “[y]ou’re allowed to take pictures in public. It’s interesting that so many people regard their surroundings as inherently private.”

That pictures of such simplicity, using subjects so mundane, can carry genuine emotional weight indicates that Hido has hit upon a theme that conveys something fundamental to the art of photography, and that these pictures, like Sultan’s Pictures from Home, are drawing upon resources residing in the nature of the camera and the medium of photograph itself. (By “drawing upon” I mean more than simply using or deploying or relying upon. Every photograph “draws upon” the medium of photography because otherwise it wouldn’t be a photograph. But not every photograph conveys to the viewer an understanding of how the physical and technological bases of photography – namely, the camera and the view of the world is captures – are given human significance by individuals committed to the making of photographs that matter as art. This achievement requires, to use the language of modernist criticism, that the work acknowledge the medium as a resource in the making of art. And acknowledging the medium means treating it not as a set of techniques and procedures applied to physical materials but as a set of norms and conventions that have throughout the history of the art been used to create works of art whose quality is not in question.)

I am drawn to write about photographs in general and Todd Hido’s in particular because although we are surrounded and inundated by photographs every day, we don’t really know what a photograph is – at least I don’t. In fact, it seems to me that the more photographs there are in the world[i], the less time and thought we give to the question of what a photograph is, what kind of object we are seeing when we look at a photograph. We fail to see just how mysterious the thing really is, and the ubiquity of photographs in the so-called “digital age” only deepens the mystery. Not so long ago, the logistics involved in making a photograph, everything from the mechanical process of regulating the encounter of light and photo-sensitive plate within the camera-box to the chemical process that allowed the image to slowly emerge on the print in the darkroom, seemed to draw on rituals of magic that create something fantastic out of mere physical material. Today there is nothing magical about using a smart-phone equipped with multiple filters and other digital enhancers to generate “selfies” that are capable of being instantly published to millions of similar hand-held devices all over the world via social media and other online platforms. In the history of human communication, has a medium ever evolved this quickly? – No wonder we don’t understand. It is the very effortless proficiency with which photographs are made, reproduced and circulated in contemporary life that ought to raise philosophical questions about what it is we are doing, because if you really look at a photograph, you’re bound to ask yourself at some point what it is you are seeing – which means, what it means to view reality by means of a photograph.

As this and my other essays on Hido's work suggest, viewing reality by means of a photograph implies that we have reached a point in human history at which the world itself is viewed from a position that is hidden, silent, unseen, powerless and at least slightly elicit - a position, in short, of being excluded from the world so viewed. All of these characterizations are given visual expression in Hido's photographs of homes at night.

[i] Todd Hido, Intimate Distance, Aperture 2016, p. 84.

1 note

·

View note

Link

In his 1686 Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton elaborated not only his famous Law of Gravity, but also his Three Laws of Motion, setting a centuries-long trend for scientific three-law sets. Newton’s third law has by far proven his most popular: “every action has an equal and opposite reaction.” In Arthur C. Clarke’s 20th century Three Laws, the third has also attained wide cultural significance. No doubt you’ve heard it: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Clarke’s third law gets invoked in discussions of the so-called “demarcation problem,” that is, of the boundaries between science and pseudoscience. It also comes up, of course, in science fiction forums, where people refer to Ted Chiang’s succinct interpretation: “If you can mass-produce it, it’s science, and if you can’t, it’s magic.” This makes sense, given the central importance the sciences place on reproducibility. But in Newton’s pre-industrial age, the distinctions between science and magic were much blurrier than they are now.

Newton was an early fellow of the British Royal Society, which codified repeatable experiment and demonstration with their motto, “Nothing in words,” and published the Principia. He later served as the Society’s president for over twenty years. But even as the foremost representative of early modern physics---what Edward Dolnick called “the clockwork universe”---Newton held some very strange religious and magical beliefs that we would point to today as examples of superstition and pseudoscience.

In 1704, for example, the year after he became Royal Society president, Newton used certain esoteric formulae to calculate the end of the world, in keeping with his long-standing study of apocalyptic prophecy. What’s more, the revered mathematician and physicist practiced the medieval art of alchemy, the attempt to turn base metals into gold by means of an occult object called the “Philosopher’s stone.” By Newton’s time, many alchemists believed the stone to be a magical substance composed in part of “sophick mercury.” In the late 1600s, Newton copied out a recipe for such stuff from a text by American-born alchemist George Starkey, writing his own notes on the back of the document.

You can see the “sophick mercury” formula in Newton’s hand at the top. The recipe contains, in part, “Fiery Dragon, some Doves of Diana, and at least seven Eagles of mercury,” notes Michael Greshko at National Geographic. Newton's alchemical texts detail what has long been “dismissed as mystical pseudoscience full of fanciful, discredited processes.” This is why Cambridge University refused to archive Newton’s alchemical papers in 1888, and why his 1855 biographer wondered how he could be taken in by “the obvious production of a fool and a knave.” Newton's alchemy documents passed quietly through many private collectors’ hands until 1936, when “the world of Isaac Newton scholarship received a rude shock,” writes Indiana University’s online project, The Chymistry of Isaac Newton:

In that year the venerable auction house of Sotheby’s released a catalogue describing three hundred twenty-nine lots of Newton’s manuscripts, mostly in his own handwriting, of which over a third were filled with content that was undeniably alchemical.

Marked “not to be printed” upon his death in 1727, the alchemical works “raised a host of interesting questions in 1936 as they do even today.” Those questions include whether or not Newton practiced alchemy as an early scientific pursuit or whether he believed in a “secret theological meaning in alchemical texts, which often describe the transmutational secret as a special gift revealed by God to his chosen sons.” The important distinction comes into play in Ted Chiang’s discussion of Clarke’s Third Law:

Suppose someone says she can transform lead into gold. If we can use her technique to build factories that turn lead into gold by the ton, then she’s made an incredible scientific discovery. If on the other hand it’s something that only she can do... then she’s a magician.

Did Newton think of himself as a magician? Or, more properly given his religiosity, as God’s chosen vessel for alchemical transformation? It’s not entirely clear what he believed about alchemy. But he did take the practice of what was then called “chymistry” as seriously as he did his mathematics. James Voelkel, curator of the Chemical Heritage Foundation—who recently purchased the Philosophers' stone recipe—tells Livescience that its author, Starkey, was “probably American’s first renowned, published scientist,” as well as an alchemist. While Newton may not have tried to make the mercury, he did correct Starkey’s text and write his own experiments for distilling lead ore on the back.

Indiana University science historian William Newman “and other historians,” notes National Geographic, “now view alchemists as thoughtful technicians who labored over their equipment and took copious notes, often encoding their recipes with mythological symbols to protect their hard-won knowledge.” The occult weirdness of alchemy, and the strange pseudonyms its practitioners adopted, often constituted a means to “hide their methods from the unlearned and ‘unworthy,’” writes Danny Lewis at Smithsonian. Like his fellow alchemists, Newton “diligently documented his lab techniques” and kept a careful record of his reading.

“Alchemists were the first to realize that compounds could be broken down into their constituent parts and then recombined,” says Newman, a principle that influenced Newton’s work on optics. It is now acknowledged that---while still considered a mystical pseudoscience---alchemy is an important “precursor to modern chemistry” and, indeed, as Indiana University notes, it contributed significantly to early modern pharmacology” and “iatrochemistry... one of the important new fields of early modern science.” The sufficiently advanced technology of chemistry has its origins in the magic of “chymistry,” and Newton was “involved in all three of chymistry’s major branches in varying degrees.”

Newton’s alchemical manuscript papers, such as “Artephius his secret Book” and “Hermes” sound nothing like what we would expect of the discoverer of a “clockwork universe.” You can read transcriptions of these manuscripts and several dozen more at The Chymistry of Isaac Newton, where you’ll also find an Alchemical Glossary, Symbol Guide, several educational resources, and more. The manuscripts not only show Newton’s alchemy pursuits, but also his correspondence with other early modern alchemical scientists like Robert Boyle and Starkey, whose recipe—titled “Preparation of the [Socphick] Mercury for the [Philosophers’] stone by the Antinomial Stellate Regulus of Mars and Luna from the Manuscripts of the American Philosopher”—will be added to the Indiana University online archive soon.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salvation by Words: Iris Murdoch on Language as a Vehicle of Truth and Art as a Force of Resistance to Tyranny

“Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify. The good artist is a vehicle of truth.”

“To create today is to create dangerously,” Albert Camus wrote in the late 1950s as he contemplated the role of the artist as a voice of resistance. “In our age,” W.H. Auden observed around the same time across the Atlantic, “the mere making of a work of art is itself a political act.” This unmerciful reality of human culture has shocked and staggered every artist who has endeavored to effect progress and lift her society up with the fulcrum of her art, but it is a fundamental fact of every age and every society. Half a century after Camus and Auden, Chinua Achebe distilled its discomfiting essence in his forgotten conversation with James Baldwin:

“Those who tell you “Do not put too much politics in your art” are not being honest. If you look very carefully you will see that they are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is… What they are saying is don’t upset the system.”

Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) — a rare philosopher with a poet’s pen, and one of the most incisive minds of the past century — explores the role of art as a force of resistance to tyranny and vehicle of cultural change in an arresting address she delivered to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in the spring of 1972, later included in the altogether revelatory posthumous collection Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library).

Two decades after the Soviet communist government forced Boris Pasternak to relinquish his Nobel Prize in Literature, Murdoch writes:

“Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify. The good artist is a vehicle of truth, he formulates ideas which would otherwise remain vague and focuses attention upon facts which can then no longer be ignored. The tyrant persecutes the artist by silencing him or by attempting to degrade or buy him. This has always been so.”

In consonance with Baldwin’s assertion that “a society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven,” Murdoch adds:

“At regular intervals in history the artist has tended to be a revolutionary or at least an instrument of change in so far as he has tended to be a sensitive and independent thinker with a job that is a little outside established society.”

In a sentiment that calls to mind the maelstrom of vicious opprobrium hurled at E.E. Cummings for his visionary defiance of tradition, which revolutionized literature, Murdoch considers how art often catalyzes ideological and cultural revolutions by first revolutionizing the art-form itself:

“A motive for change in art has always been the artist’s own sense of truth. Artists constantly react against their tradition, finding it pompous and starchy and out of touch… Traditional art is seen as far too grand, and is then seen as a half-truth.”

Murdoch counts among the “multifarious enemies of art” not only the deliberate assaults of political agendas and ideologies, but the half-conscious lacerations of our technology — that prosthetic extension of human intention, the unforeseen consequences and byproducts of which invariably eclipse its original intended uses. In a passage of sundering pertinence to our present political pseudo-reality, reinforced by the gorge of incessant newsfeeds, she writes:

“A technological society, quite automatically and without any malign intent, upsets the artist by taking over and transforming the idea of craft, and by endlessly reproducing objects which are not art objects but sometimes resemble them. Technology steals the artist’s public by inventing sub-artistic forms of entertainment and by offering a great counterinterest and a rival way of grasping the world.

[…]

Today technology further disturbs the artist and his client not only by actually threatening the world, but by making its wretchedness apparent upon the television screen. The desire to attack art, to neglect it or to harness it or to transform it out of recognition, is a natural and in a way respectable reaction to this display.”

In a lovely parallel to Kurt Gödel’s landmark incompleteness theorem, demonstrating the existence of certain mathematical truths which mathematical logical simply cannot prove, Murdoch extols incompleteness as the hallmark of art — not its weakness but its supreme strength:

“Great art, especially literature, but the other arts too, carries a built-in self-critical recognition of its incompleteness. It accepts and celebrates jumble, and the bafflement of the mind by the world. The incomplete pseudo-object, the work of art, is a lucid commentary upon itself… Art makes a place for precision in the midst of chaos by inventing a language in which contingent details can be lovingly noticed and obvious truths stated with simple authority. The incompleteness of the pseudo-object need not affect the lucidity of the mode of talk which it bodies forth; in fact, the two aspects of the matter ideally support each other. In this sense all good art is its own intimate critic, celebrating in simple and truthful utterance the broken nature of its formal complexity. All good tragedy is anti-tragedy. King Lear. Lear wants to enact the false tragic, the solemn, the complete. Shakespeare forces him to enact the true tragic, the absurd, the incomplete.

Great art, then,… inspires truthfulness and humility.”

Much as the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay had ranked an art other than her own as the greatest — “Even poetry, Sweet Patron Muse forgive me the words, is not what music is,” she exulted in one of literature’s most splendid passages about the power of music — Murdoch concedes the superior power of art at the expense of her own primary vocation:

“Great art is able to display and discuss the central area of our reality, our actual consciousness, in a more exact way than science or even philosophy can.”

A decade and a half before Toni Morrison delivered her spectacular Nobel Prize acceptance speech on the power of language and a quarter century before Susan Sontag’s poignant address on “the conscience of words,” Murdoch writes:

“There is no doubt which art is the most practically important for our survival and our salvation, and that is literature. Words constitute the ultimate texture and stuff of our moral being, since they are the most refined and delicate and detailed, as well as the most universally used and understood, of the symbolisms whereby we express ourselves into existence. We became spiritual animals when we became verbal animals. The fundamental distinctions can only be made in words. Words are spirit.”

In a sentiment of grave poignancy amid our dispiriting and decivilizing atmosphere of “alternative facts,” Murdoch adds:

“The quality of a civilisation depends upon its ability to discern and reveal truth, and this depends upon the scope and purity of its language.

Any dictator attempts to degrade the language because this is a way to mystify. And many of the quasi-automatic operations of capitalist industrial society tend also toward mystification and the blunting of verbal precision.”

With an eye to C.P. Snow’s famed 1959 lecture “The Two Cultures” — a watershed case for the necessity of desegregating science and the humanities, of bridging investigation with imaginative experience — Murdoch exhorts:

“We must not be tempted to leave lucidity and exactness to the scientist. Whenever we write we ought to write as well as we can… in order to defend our language and render subtle and clear that stuff which is the deepest texture of our spirit.

[…]

There are not two cultures. There is only one culture and words are its basis; words are where we live as human beings and as moral and spiritual agents.”

Her closing words are part manifesto and part benediction — a meta-testament to the mobilizing, spiritualizing power of great writing:

“Both art and philosophy constantly re-create themselves by returning to the deep and obvious and ordinary things of human existence and making there a place for cool speech and wit and serious unforced reflection. Long may this central area remain to us, the homeland of freedom and of art. The great artist, like the great saint, calms us by a kind of unassuming simple lucidity, he speaks with the voice that we hear in Homer and in Shakespeare and in the Gospels. This is the human language of which, whenever we write, as artists or as word-users of any other kind, we should endeavour to be worthy.”

Existentialists and Mystics — which also gave us Murdoch on storytelling and the key to great writing — is a timelessly incisive read in its entirety. Complement this particular fragment with Toni Morrison on the power of language, then revisit Murdoch on causality, chance, and how love gives meaning to our existence and her almost unbearably beautiful love letters.

Source: Maria Popova, brainpickings.org (12th February 2019)

#quote#women writers#art#creativity#truth#existential musings#all eternal things#love in a time of...#intelligence quotients#progressive thinking#language matters#more than words#stands on its own#elisa english#elisaenglish

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Architectural History of Yharnam || 2018 Developments

I’ve returned to writing this. Below are some snippets. If this is going to be a historical text, I see no reason to exclude bits of stuffy academic debates.

“The age is running mad after innovation; all the business of the world is to be done in a new way; men are to be hanged in a new way; the world itself is not safe from the fury of innovation…”

A certain narrow-minded self-importance and xenophobic insularity can be discerned by Yharnam citizens’ popular adoption of “castle” at one point as a way of referring to their homes.

Winkmann became a theoretician for the Sidereal movement, writing:

“Those who have hitherto written of aesthetics, from laziness rather than a lack of knowledge, have fed us with metaphysical ideas. They have imagined an infinity of beauties and have perceived them in Labyrinthine statues, obelisks, and archways, but instead of showing them to us they have talked about them in the abstract, as though all the designs and monuments had been destroyed or lost. Therefore, to treat of the art of design of the Ancients and to point out its excellence both for those who admire it and for artists themselves, it is necessary to come from the ideal to the sensible, from the general to the particular; and to do this, not with vague and ill-defined discussions, but with a precise determination of those outlines and delineaments which produce those appearances that we call virile, powerful, and beautiful forms.”

“The works of man are at times like man himself. Primitive works of art, incomplete, coarse, which expose the indecisiveness of inexperience, or the stabbings for a procedure, are often more useful, more worthy of attention, and more instructive than other works seemingly more elegant, correct in their general conception, more studied or cleverly executed, but which commit the grave error of revealing nothing to the spirit.”

One can see a subsequent enactment of these principles in the upper cathedral ward, with its Pthumeric sculptures and usage of broad and massive forms possessing a technical refinement surpassing Old Yharnam’s, broad and massive itself. Yet one can also recognize within this call for first-hand observation a disinterest in its applicability to Yharnam’s contemporary culture; Winkmann makes no mention of Yharnam’s broader organizational or hygienic needs. An article by Telville, a rare example of a call for seeing aesthetics from a historical perspective, comprises one of a few contrary responses:

“The very position of Winkmann and writers of his ilk has led them to relish an unlimited detachment from pragmatics; and so they have become much bolder in their novelties, more enamored of supposed ancient wisdom and more confident still in their individual reason. No matter how close such men have ever come to reproducing and elaborating on the Ancients’ work, this whole derivative system is inescapably based on an initial conception, that of attributing an essential and super-historical character to a particular choice. The supposed universality of the Ancients’ architecture is an attribute given by history, not inherent in their nature. Why shall we worship tombs?”

If Yharnam’s architecture was admired by “outlanders”, it was primarily because of its methods. The process, and not the building, was coveted. Even so, a number of articles in architectural journals attest to a begrudging interest in Yharnam’s “bizarreness.” In the same article, Henri condemns Yharnam by stating, “It is no longer architecture,” and yet later on also describes its buildings as “an art truly individual which does not find its equivalent with us.” Time and again, there is a reformulation of the idea that Yharnam’s architecture may finally blossom into something admirable when, but only when, more rhythm, fitness, proportion, and dignity are added to its “picturesque” qualities. Until then, it would be original but not proper.

Whatever sympathies or antipathies later readers may have with the involved parties, it must be noted that the external critics of Yharnam’s architecture generally only had second-hand contact, neglected to give authorial attribution to designs, and were primarily informed by exterior illustrations in journals -- illustrations which were accurate and yet only partial. Such illustrations excluded the interrelationships of technology, plan, and elevation; more than that, there was no sociological dialogue between those distantly interested and the inhabitants of their objects of criticism. To them, the architecture was an inexplicable organism that acted independently of its inhabitants. Yharnam would go on to have a reputation for fierce xenophobia, but at one point it encouraged outsider eyes looking in.

“We are becoming wonted to having foreigners write amiable and appreciative criticism on the work that our architects are doing. Many foreign critics have a way of discussing the matter that leaves more sting than balm behind.”

^ Bringing in the other angle of external critics having their own blindspots even when criticism may be applicable; reflecting late-19th century tensions and maintained ignorance between the US and France; the idea here being that Yharnam's architecture was reflective of some social and cultural norms, themselves criticizable, but that the architecture was not an inexplicable organism as foreign criticism seemed to treat it. Emphasize the theme of architectural theoreticians and the non-intellectual citizenry developing separately and yet somehow in tandem: the theory is myopically formal, but it's embraced by society as signifiers of civic pride and proof of an especial creative talent (emboldened as xenophobia later on, its own sort of myopia)

Architecture was severed from the important problems of its time: the artists, who should have been concerned with the aims of architectural production, isolated themselves with imaginary or purely formal problems, prolonging the myth that architecture could control society and that its aesthetic properties were somehow spiritual; and the engineers, concentrating on the means of realizing their creations, forgot the ultimate aim of their work and allowed themselves to be used to any end whatsoever. At the same time, it must be noted that Yharnam’s classes very much enjoyed the architectonic variety these debates produced, and seem to have become only more emboldened when external criticism was directed their way. Why shouldn’t Yharnam’s working class, eventually emerging as a financially empowered middle class with luxuriant tastes, enjoy the fruits of its industry and visual inventiveness?

Over time, Yharnam's governing classes and institutions came to hold the belief that one need only concern oneself with the single enterprise for a balance to eventually reassert itself throughout the whole. The elite believed that they were moving towards a “natural” and “enlightened” order, one that more truthfully reflected an underlying cosmological paradigm, knowable from the analysis of its elements, like the Byrgenwerthian corpuscular theory of the natural world. The structures of traditional societies -- the political privileges of Cainhurst’s feudalism, the organization of Yharnam’s medicinal and industrial economies -- appeared as collapsable trifles to be removed suddenly and violently so that the world could move forward into the imagined natural order. Any outcome was morally justifiable, for it would reflect ostensible scientific truisms: the strong would survive the revolution, and the weak would at best be guinea pigs.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

7.1 The Aura

Walter Benjamin’s (2008) theory of the Aura describes a cheapening/lessening of the inherent value and specialness of a work of art once it is mechanically reproduced. He considers the Aura of a piece to be its quality of originality in its place in history, culture, and time, as well as the exact physicality of a work. Once a piece is reproduced, it loses aspects of its Aura, whether that be its place in culture/history, or the nature of its physicality (for example, turning an oil painting into a print in reproduction); this negatively affects the way audiences view and interact with a work.

I can see some truth to Benjamin’s theory when considering merchandise for artworks such as socks, t shirts, or ties with images of famous works on them. There is a distinct separation and difference after witnessing a work of art in that manner. I am not against this kind of reproduction, but can see where Benjamin is coming from when facing this specific example. However, I don’t believe Benjamin’s theory holds much truth when comparing it to contemporary art that was specifically designed for commodities. I think reproductions of Warhol’s work for example do not lose their Aura due to the original works being created with such commercialized care and intent. How can we claim that type of art loses an Aura during reproduction when the authenticity of that work is inherent to its commercial nature?

I found two articles defending mass produced art as authentic art. They both exemplify easily mass produced works such as photographs and prints, and support these works as art through their aesthetic nature. Vassilev (2023) argues that changing society creates allowances for mass art to function as more historic art forms used to. Chapman (2003) emphasizes the artistry of such works despite their mass reproducible nature.

References

Benjamin, W. (2008). The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, second version. In M. W. Jennings, B. Doherty, & T. Y. Levin (Eds.), The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media (E. Jephcott, R. Livingstone, H. Eiland, et al., Trans.). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Chapman, L. H. (2003). Studies of the Mass Arts. Studies in Art Education, 44(3), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2003.11651741

Vassilev, K. (2023). The Aura of the Object and the Work of Art: A Critical Analysis of Walter Benjamin’s Theory in the Context of Contemporary Art and Culture. Arts 12, no. 2: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12020059

0 notes

Text

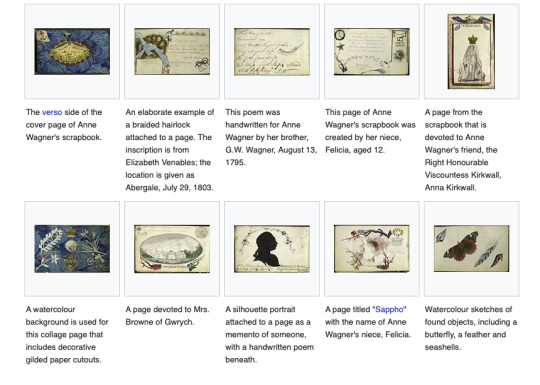

Scrapbooking Research

taking a photo of something impairs your memory of it

we give less attention to the experience because we are more focused on taking the photo - and we know the memory/ experience will be safely stored in a photo

photo taker’s memory will suffer when they take a photo whether they expect to keep it or not

longtime partners or friends will distribute memory demands between them so one will remember thing the other doesn't need to

cameras force us to disengage from properly taking in the stimulus as our attention flows to the mechanics of taking the photo

digest.bps.org.uk/2018/05/31/taking-a-photo-of-something-impairs-your-memory-of-it-but-the-reasons-remain-largely-mysterious/

‘pics of it didn't happen’

selfie generation implies that its a new phenomenon, but tourist have always found people to take photos of them

psychologist Sigmund Freud wrote “I only have to bear in mind that place where this ‘memory’s been deposited and I can then ‘reproduce’ it at any time I like, with the certainty that it will have remained unaltered and so have escaped the possible distortions to which it might have been subjected to in my actual memory”

the irony of photography is that it is just as vulnerable to distortion as any other record.

telegraph.co.uk/technology/preserving-memories/why-do-we-take-photos/

memories of our experiences are called autobiographical memories an they rely on a brain region called hippocampus

without the hippocampus, you would be stuck in time and memories of new experiences would rapidly fade

photographs act as memory storage and viewing a photo can activate memory recall

vision is the strongest and most influential in memory formation - through memory and anatomical studies, the neural pathways from the eye to hippocampus have been well mapped out

petapixel.com/2013/07/20/memories-photographs-and-the-human-brain

if you are in the image you're looking at, you become more removed from the image - as if you're an observer

if you're not in the image, you return to first person and relive the experience though your own eyes

Cognitive offloading

“if you snap a shot and share it, you're going to be able to relive that experience with other. if you don't, its going to be isolated to yourself”

Collaborative memory benefits

new info is prompted be a chain of conversation through 2 parties

richer, more vivid description of events incl. sensory info

info from one person showing things in a new light to the other

Scrapbooking

method of preserving, presenting and arranging personal and family history in the form of a book, box or card

typical memorabilia include phots, printed media, and artwork

often decorated and contain extensive journal entires or written description

scrapbooking stared in the tUK in the 19th century

commonplace books

popular in England in the 15th century - emerged as a way to compile information incl. recipes, quotes, letters, poems - unique to creator’s interests

friendship albums