#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )

Photo

【Reference Artifacts】

・China Han Dynasty Female Sitting & Dancer Figurines

・Plain yarn garment (straight) Mawangdui No. 1 Han Tomb (Xinzhui),China

material: silk,size: dress length 132 cm, sleeve length 181.5 cm

・ Floss silk padded robe,Mawangdui No. 1 Han Tomb (Xinzhui) ,China

length: 140 cm, overall length of the sleeves: 245 cm, width at waist: 52 cm

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE ) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Photoshoots【 西汉舞俑 】

________________

💃🏻Model:@尔七七七七

💄Stylist: @仰望的花鼻子

📸Photo: @realyn

👗 Hanfu: @山涧服饰

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/5541803701/MwDiCs1G9

________________

#Chinese Hanfu#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )#chinese traditional clothing#Chinese historical fashion#hanfu history#chinese#Chinese Culture#Chinese Costume#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#China History#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#漢服#汉服

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cocoon Flask, 206 BCE–9 CE / China, Western Han dynasty

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) was the second dynasty of Imperial China (the era of centralized, dynastic government, 221 BCE - 1912 CE) which established the paradigm for all succeeding dynasties up through 1912 CE. It succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and was followed by the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE).

It was founded by the commoner Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE; throne name: Gaozu r. 202-195 BCE) who worked toward repairing the damage caused by the repressive regime of the Qin through more benevolent laws and care for the people. The dynasty is divided into two periods:

Western Han (also Former Han): 202 BCE - 9 CE

Eastern Han (also Later Han): 25-220 CE

Read More Here

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) was the second dynasty of Imperial China (the era of centralized, dynastic government, 221 BCE - 1912 CE) which established the paradigm for all succeeding dynasties up through 1912 CE. It succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and was followed by the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE).

It was founded by the commoner Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE; throne name: Gaozu r. 202-195 BCE) who worked toward repairing the damage caused by the repressive regime of the Qin through more benevolent laws and care for the people. The dynasty is divided into two periods:

Western Han (also Former Han): 202 BCE - 9 CE

Eastern Han (also Later Han): 25-220 CE

The separation is caused by the rise of the regent Wang Mang (l. 45 BCE - 23 CE) who declared the Han Dynasty finished and established the Xin Dynasty (9-23 CE). Wang's idealistic form of government failed and, after a brief period of turmoil, the Han Dynasty resumed.

Gaozu initially retained the Qin Dynasty's philosophy of Legalism but with less severity. Legalism gave way to Confucianism under the most famous monarch of the Han, Emperor Wu (also given as Wudi, Wuti, Wu the Great, r. 141-87 BCE) who, among his many other impressive achievements, also opened the Silk Road, establishing trade with the West. The Han also negotiated a peace, which was more or less observed, with the nomadic peoples of the Xiongnu and Xianbi to the north and the Xirong to the west which stabilized the borders and encouraged peace and cultural development in the arts and sciences. Many of the commonplace items taken for granted today were invented by the Han such as the wheelbarrow, the compass, the adjustable wrench, seismograph, and paper, to name only a few.

The Han also restored the cultural values of the Zhou Dynasty, which had been discarded by the Qin, encouraged literacy, and the study of history. The historian Sima Qian (l. 145/35-86 BCE) lived during this period whose Records of the Grand Historian set the standard and form for Chinese historical writings up through the 20th century CE. Chinese mythology and religion also developed during this time including the popular messianic movement focused on the Queen Mother of the West.

By c. 130 CE, however, the imperial court had become corrupt with eunuchs exercising more actual power than the Chinese emperor. By the time of the emperor Lingdi (r. 168-189 CE), the Han royal house had less actual authority than the palace eunuchs and the generals (who were more or less autonomous warlords) stationed at the borders of the country. In 184 CE, the Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in response to high taxes and famine and these generals put it down.

Among them was Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE) who, afterwards, waged war against his fellow commanders for control of the state. He was defeated at the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 CE after which the country was divided between three kingdoms and the Han Dynasty fell. Its legacy is so profound that it continues to the present day and the majority of ethnic Chinese refer to themselves as Han People (Han rem) proudly in identifying themselves as descendants of the great ancient dynasty.

#studyblr#history#military history#politics#chinese politics#philosophy#technology#invention#qin dynasty#han dynasty#western han#eastern han#xin dynasty#three kingdoms#battle of red cliffs#yellow turban rebellion#china#xiongnu#xianbei#xirong#emperor gaozu of han#wang mang#emperor wu of han#sima qian#emperor ling of han#cao cao#legalism#confucianism#silk road

0 notes

Text

*Xin Dynasty* Weiyang Palace Site

The majestic ruins of Weiyang Palace, once the political and cultural heart of the Western Han Dynasty. The ancient aura that permeates the air is nothing short of magical. Nestled on the northern outskirts of Xi'an, the Weiyang Palace Site boasts a history dating back more than two millennia. This archaeological treasure trove served as the imperial palace during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE). Commissioned by Emperor Wu, it stood as a symbol of political power and cultural innovation.

Dating back to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE), the Weiyang Palace was a sprawling complex that once stood as the imperial residence of Liu Bang, the founding emperor of the Han Dynasty. The palace was a symbol of power, opulence, and the political prowess of the ruling dynasty. Over the centuries, the Weiyang Palace underwent numerous renovations and expansions, transforming into a grand architectural masterpiece. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the Weiyang Palace experienced yet another period of glory. Emperor Taizong, the second emperor of the Tang Dynasty, expanded the palace, adding more structures and enhancing its magnificence. It became a center of political, cultural, and social activities during this golden age of Chinese civilization.

Tragically, the Weiyang Palace fell victim to the ravages of time and war. Despite its historical significance, much of the palace was destroyed during the transition from the Tang to the Song Dynasty. The remnants of this once-imposing complex were buried beneath layers of earth and forgotten by the sands of time. Rediscovered during archaeological excavations in the 20th century, the Weiyang Palace Site has since become a window into the past. Visitors can explore the unearthed foundations and marvel at the remnants of ancient structures.

Today, the Weiyang Palace Site stands as a poignant reminder of China's rich history and the cyclical nature of empires. Its rediscovery and preservation serve as a testament to the importance of safeguarding our cultural heritage, allowing future generations to connect with the roots of their civilization and appreciate the enduring legacy of the Weiyang Palace.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dragon Sculptures Evidence of Ancient Cultural Exchange Between China and Mongolia

Two gilded silver dragon figurines featuring detailed horns, eyes, teeth, and feathers have been discovered in a Xiongnu elite tomb in north-central Mongolia. The dragons bear obvious characteristics of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 9 CE). They are evidence of the cultural exchange and interaction between the prairie in the north and central China, as well as the high status of the Xiongu buried in the tomb.

Of course, the silver dragons were not the only rich items they were buried with: a trove of gold, silver, bronze, jade and wood artifacts have also been found.

225 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade Disk - China, Western Han dynasty (206 BCE - 9 CE)

Freer / Sackler Galleries - The Dr. Paul Singer Collection

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underwater City: Unveiling The Secrets At The Bottom Of Fuxian Lake

A mystery lies scattered on the unexplored bottom of Fuxian Lake, stretching out through Chengjiang County, Jiangchuan County and Huaning County in Yunnan Province, about 60 kilometers to Kunming City, China. The lake is rising 1,720 meters above sea level and encompassing 212 square kilometers of land.

The deepest part of the lake descends 157 meters; the Fuxian Lake is the second deepest freshwater lake in China.

One day, Geng Wei, a specialized diver, accidentally found a strange phenomenon under the lake, in form of stone materials including flagstones and stone strips with thick moss above them, could be seen.

According to an ancient local legend, a city-like silhouette under the lake from the nearby mountains can be clearly seen on a fine, calm day. To find out if there is something hidden in the calm waters of the lake, a Chinese submarine archaeology team stationed in Fuxian Lake carried on surveys and with advanced use of detectors, discovered lots of blocks scattered on the lake bottom, stones that formed a wall seen on a sonar display along with various flagstones.

High stairs appeared in front of them and flagstones covered with moss seemed to reveal an ancient sunken city. The team members found the scope of the site under Fuxian Lake was extremely big, and the traces of construction were everywhere along with earthenware.

Could the underwater site be the ancient city of Yuyuan, which disappeared mysteriously many hundreds of years ago?

Was the site under the lake the city recorded in The Book of Han (Hanshu), a classic Chinese historical writing covering the history of the Western Han Dynasty, 206 BCE-9 CE, that once recorded that Yuyuan City was north of Fuxian Lake?

After several days of observation, sonar scans and analyses, experts estimated the scope of the area is between 2.4 square kilometers to 2.7 square kilometers, and the site was possibly from the Warring States (475-221 BC) to the Eastern Han Dynasty. However, in order to find a more exact time, they had to find a subject that could be used for carbon 14 testing.

Additionally as reported, eight main buildings were found all under the water, including a round, colosseum-like building with a 37 meter wide base and a gap to the northeast and two large high buildings with floors, similar to the Mayan pyramids.

One of the large, high buildings has three floors, a 60 meter wide base and lots of small steps linking the floors. Another is even larger, with a 63 meter wide base standing five floors (totally 21 meters high).

A 300 meter long and 5 to 7 meter wide rock road connects the two buildings.

Carbon-14 dating of some shells attached to blocks they were 1750 years old, which means the site sunk during the Han period. However in the Tang Dynasty, there were still records about Yuyuan City remaining on land.

Therefore, the lost city was not Yuyuan, but rather the ancient unidentified structure of the under-lake construction, could represent the remains of the ancient Dian Country – a country with a high level of civilization that after 86 BC – mysteriously disappeared.

Fuxian Lake is a very large body of water – is still unexplored, so various legends have prevailed for more than 1,000 years and unfortunately their credibility cannot be confirmed.

According to one story mentioned in “Cheng Jang Fu Zhi”, a book in the region of Emperor Daoguang, a horse-like animal lived in the lake. Its body was pure white with red spots on its back. Sometimes it rapidly flew out of the water.

Was this strange animal perhaps a vehicle which modern ufologists today call – uso (unidentified submerged object)?

....

We are a race with amnesia. There is so much out there forgotten, unfortunately. There were amazing civilizations here from every single cultural groupings. Humanity has a history untold as of yet.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: From a Jade Burial Suit to Terracotta Warriors, a Blockbuster Display of China’s Ancient Treasures

Jade (nephrite) burial suit of Dou Wan from the Western Han dynasty (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

When the Han Dynasty princess Dou Wan died some 2,000 years ago, her corpse was encased within 2,160 small plates of solid jade. Carefully strung together with 700 grams’ worth of gold thread, the green stones formed a glistening cocoon that conformed to the contours of her body, intended to preserve it for eternity. That jade burial suit, recovered with her husband’s in 1968 from their tombs in the northern Chinese province of Hebei, is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s one unmissable, standout artifact in a blockbuster exhibition showcasing the rich artworks that emerged during two of China’s most pivotal dynasties.

Fluted column with dragons and Chinese inscriptions (2nd century CE)

Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties is impressive in logistics alone. The over 160 objects arrive on loan from 32 museums and archaeological institutions in China — just think of the bureaucratic hurdles, never mind the shipping — and most have never before been displayed in the West. The exhibition is intended as a kind of visual summary of archaeological findings, mostly from shrines and underground tombs of royals, from the last half-century. The result showcases the remnants of 400 years of innovation and craftsmanship, developed to suit the visions of an increasingly unified state.

The long histories of the Qin and the Han dynasties, which witnessed the centralization of government and the standardization of everything from laws to the economy to written language, are glossed over in a handful of wall texts. The exhibition relies largely on visual splendor, with the objects, most of which are accompanied by short descriptions, serving as traces of a clearly astounding past. That this didn’t bother me is a testament to the allure and evocative power of almost every piece on view, from tiny jade pigs intended to serve as hand warmers for the dead to a life-size, terracotta statue depicting a rotund strongman — a performer in an acrobatic troupe who likely entertained the imperial court of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi. (Detailed historical context, for those who seek it, can be found elsewhere, in the show’s dense catalogue.)

As the museum’s curator of Chinese art, Zhixin Jason Sun, writes in a catalogue essay, “These remarkable objects attest to the unprecedented role of art as spectacle, and more importantly, reflect changes in political, social, economic, and religious aspects of public life.”

Strongman from Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE)

Installation view of Age of Empires at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Organized chronologically, Age of Empires begins with what are probably the most recognized jewels of ancient Chinese art outside of that country: five examples of the terracotta warriors from Qin Shihuangdi’s mausoleum complex, along with eight nearly life-size earthenware horses pulling two chariots (modern replicas of Qin originals). It’s a crowd-pleasing introduction, but also one that exemplifies the naturalism that characterized Qin works: the curved forms of the frozen archers, originally painted, are particularly elegant, and you’ll notice that each warrior bears an individual visage. It’s easy to forget that the results of this painstaking labor were never intended for our world of the living, produced to reside underground for eternity and endure as markers of an emperor’s eternal power.

The majority of what follows dates to the Han Dynasty, which the peasant rebel leader Liu Bang founded in 206 BCE. Although most objects were created for funerary use, they aren’t generally somber in appearance, a reminder that the Han viewed the afterlife as a realm where pleasure should flourish. A tomb of a prince of the Chu state, for instance, yielded a group of small, earthenware models of dancers and musicians. Although their faces are blank, their active poses convey a palpable energy, as if a snap of the fingers could magically awaken them to continue performing. One statue of a curved female dancer is particularly mesmerizing, with her wide sleeves billowing to form tall parabolas. She looks like she’s doing the wave with her entire body.

“Female Dancer” figure from the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE)

“Female Musician Playing a Flute or Panpipe” figure from the Western Han Dynasty

Mausoleums were built as extensive replicas of real-world residences, so most of the objects in Age of Empires are more quotidian in nature. Their occupants spared no expense, however, ordering artisans to create lacquered tableware, skillfully woven silk textiles, furnishings that boast intricate metalwork. Smaller versions of buildings stood in funerary complexes, too, as models of grand homes that conveyed an owner’s status and power. One luxury, multistory structure is so realistic, it even has a tiny guard dog sitting by its entrance. Animals themselves were popular subjects for standalone works. Some species were considered auspicious symbols, while others represent the exotic creatures that populated imperial zoos. An entire gallery at the Met is filled with animals, from elephants to cows, sculpted in a variety of materials.

While the Han developed and honed the imperial policies established by the Qin at home, it was busy engaging beyond China’s borders as well. Some of the most intriguing artifacts on view speak to the growing trade networks that resulted from the Han’s military and diplomatic campaigns. Beautiful objects integrate precious materials from places such as Persia, India, and Sumatra, while other artifacts reveal foreign influences more explicitly: for instance, the unique mix of culture in a Hellenistic fluted stone column that bears a Chinese inscription. Then there’s a comical lamp with a fuel chamber shaped like a Southeast Asian man, who hovers in the air, attached to chains — a design borrowed from the ancient Mediterranean.

“Hanging Lamp in the Shape of a Foreigner” from the Eastern Han dynasty

Although many of these objects were made for individuals, their specific identities and stories aren’t highlighted here. Most of the works are placed in glass cases or set on protective pedestals, presented as priceless artifacts displaced from their original, funerary contexts. Its unique construction aside, the jade suit of Dou Wan stuns because it represents a real body. To turn a corner and suddenly behold the otherworldly armor lying still in its own room is jarring. But it’s also stirring, with that mass of protective stone reminding us of the very human uncertainties and fears behind every material affirmation of power.

Lamp in the Shape of a Mythical Bird from the Western Han dynasty

“Brick with Ax-Chariot” from the Eastern Han dynasty

Terracota armed warriors from the Western Han dynasty

Tomb Gate from the Eastern Han dynasty

Dog from the Eastern Han dynasty

Lidded box and jade bear from the Western Han Dynasty

Elephant and Groom from the Western Han dynasty (2nd century BCE)

Detail of jade (nephrite) burial suit of Dou Wan from the Western Han dynasty

Hardstone jade pigs that served as “hand warmers” from the Western Han dynasty

Model of a multistory house from the Eastern Han dynasty

Cowry Container with Scene of Sacrifice from the Western Han dynasty

Bronze horse and groom from the Eastern Han Dynasty

“Standing Archer” figure from the Qin dynasty

Groups of chariot drivers, chariot riders, and infantrymen from the Western Han dynasty

Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220) continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through July 16.

The post From a Jade Burial Suit to Terracotta Warriors, a Blockbuster Display of China’s Ancient Treasures appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rRMhAE

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

Until 1530, sculptural images of Confucius and varying numbers of disciples and later followers received semiannual sacrifices in state-supported temples all over China. The icons' visual features were greatly influenced by the posthumous titles and ranks that emperors conferred on Confucius and his followers, the same as for deities in the Daoist and Buddhist pantheons. This convergence led to visual conflation and aroused objections from Neo-Confucian ritualists, culminating in the ritual reform of 1530, which replaced images with inscribed tablets and Confucius s kingly title with the designation Ultimate Sage and First Teacher. However, the ban on icons did not apply to the primordial temple of Confucius in Qufu, Shandong. Post-1530 gazetteers publicized the distinction by reproducing a line drawing of this temples sculptural icon, and persistent replications of this image helped to popularize his cult. The same period saw a proliferation of non-godlike representations of Confucius, including his portrayal as a teacher, whose iconographic origins can be traced to a painted portrait handed down through generations of his descendants. In recent years, variations of this teacher image have become the basis for new sculptural representations, first in Taiwan, then in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora, and finally on the mainland. Now installed at sites around the world, statues of Confucius have become a contested symbol of Chinese civilization.

Julia K. Murray, "Idols" in the Temple: Icons and the Cult of Confucius, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 68, No. 2 (May, 2009), pp. 371-411.

Various efforts in recent centuries to foreground the moral dimension of Confucius’s legacy have obscured practices and beliefs involving icons, along with other religious aspects of Confucianism. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jesuit missionaries tried to convince papal authorities in Rome that Confucianism was an ethical philosophy (Jensen 1997, 63-70, 129), so that efforts to spread Christianity in China would not be stymied by requiring converts to give up rituals for worshiping Confucius Similarly, in the nineteenth century, the Protestant missionary-translator James Legge argued that the ancient Confucian classics merely needed to be supplemented with Christianity, just as the Bibles Old Testament was completed by the New Testament (Mungello 2003, 590). Moreover, from the sixteenth century onward, Confucian temples were austere buildings where inscribed tablets were displayed, unlike Buddhist temples and popular-cult shrines with sculptural icons in sensuous pro fusion.2 Although Kang Youwei (1858-1927) sought to establish Confucianism as Chinas official religion (zongjiao) at the end of the nineteenth century, on the model of Christianity in Western nations, he made little headway before falling from power in the coup that reversed his 1898 reforms (Chen 1999; Goossaert 2005, 2006). Because regular worship of Confucius was on the official Register of Sacrifices (Sidian), and thus was closely identified with the imperial system, the collapse of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) undercut subsequent efforts to create a religion based on Confucianism. In the early decades of the twentieth century, some nationalist modernizers wanted to discard Confucius altogether, while others found it expedient to present him as Chinas counterpart to the Wests great rational philosophers. Suppressing what they considered to be idolatry and superstition, they emphasized a Confucius who did not concern himself with "ghosts and spirits." And in recent years, global advocates of "New Confucianism" have focused on his ideas about self-cultivation and morality.3 To some, Confucian concepts of reciprocal responsibility in a hierarchical society suggest an Asian alternative to Western-style democracy. These different efforts have created a widespread conception of Confucianism that is defined by a set of ancient texts, the civil service examination system based on their mastery, and the promotion of social virtues such as benevolence (ren), filial piety (xiao), propriety (li), and righteousness (yi).

[...]

Other conceptions of Confucius emphasized his roles as a teacher and as an expert on ancient ritual, instead of as a preternaturally insightful and prescient leader who communed with heaven. In some parts of the Analects (Lun yu), Confucius is portrayed as a human being who endured much travail and disappointment, especially while traveling the ancient states in search of a ruler who would take his advice (Csikszentmihalyi 2002).7 By the late Eastern Han period, this more mundane Confucius had largely overshadowed the superhuman figure. Nonetheless, the messianic sage was featured in the so-called apocryphal texts (weishu It H) of the late Han and post-Han periods (e.g., Wang Jia 1966,3:4?5). In addition, the "modern text" traditions retained their vitality in South China well into the Period of Disunion (Wilson 1995, 32). Furthermore, the Kong lineage perpetuated and embellished the legends in oral traditions and written genealogies, even down to the present day.8 Claiming descent from Confucius, lineage members had a vital interest in preserving a heroic conception of their ancestor and in maintaining their own cohesion (Wilson 1996). Emperors from the Han through the Qing dynasties awarded noble titles, tax exemptions, official positions, and lands to the descendants who maintained sacrifices to Confucius in Qufu.

Although the earliest forms of veneration and sacrifice to Confucius occurred in funerary and memorial contexts, the observances themselves increasingly displayed the features of a deity cult. Confucius continued to receive sacrifices at his grave long past the normal period for commemorative worship (Jensen 2002, 180-86; Sima 1982, 47:1945). Moreover, persons with no blood relation to him made these offerings, contrary to the customs of familial worship, which prescribed that a son should lead funerary rites?but Confucius s son had predeceased him. After Confucius died in 479 BCE, his disciples carried out the rites of mourning, and the especially devoted Zi Gong M kept a six-year vigil in a hut beside the burial mound (Sima 1982, 47:1945). Local authorities maintained offerings at this site for generations afterward. The place where Confucius had gathered with his disciples became a memorial hall, and his personal effects were displayed there. The Grand Historian Sima Qian (145-86 BCE) reported seeing the masters clothes, cap, zither (qin), books, sacrificial vessels, and carriage in the memorial hall when he visited Qufu. In 195 BCE, the Han founding emperor Gaozu (r. 206-195 BCE) performed a grand sacrifice (tailao X ?) to Confucius in Qufu, offering an ox, sheep, and pig, along with wine and other foodstuffs (Sima 1982, 47:1945-46). In 136 BCE, Han Wudi (r. 141-87 BCE) canonized the textual tradition of Confucius and his followers by abolishing the posts of Erudite (boshi) held by court scholars who were experts in texts belonging to other traditions (Wilson 1995, 29). Other Han emperors awarded posthumous titles of nobility to Confucius and gave material support to his descendants and cult, providing for semiannual sacrifices in Qufu after 169 CE (Wilson 2002c, 261).

By the third century, sacrifices to Confucius were also being performed elsewhere, typically in academic settings. The first sacrifice documented outside Qufu took place in 241 CE at the imperial university (Biyong) in Luoyang, the capital of the kingdom of Wei (220-65), and several more were per formed there under the Western Jin dynasty (265-316) (Wilson 2002b, 74).9 During the centuries of disunion, various northern and southern regimes established state-sponsored temples in their capitals for conducting sacrifices to Confucius and his legacy.10 The Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties continued this practice in a reunified empire. The Tang founding emperor Gaozu (r. 618-26) established a temple at the National University (Guozi xue) in Chang'an (modern Xi'an, Shaanxi) and personally sacrificed there in 624 (Ouyang 1975, 1:9, 17). The Tang eastern capital at Luoyang also had an imperially sponsored temple. Initially, it was the Duke of Zhou JH the wise regent to the young heir of the Zhou dynasty founder, who was honored as First Sage (Xian sheng), and Confucius received sacrifice as Correlate (Fei) and First Teacher (Xian shi). In 628, a memorial submitted by Fang Xuanling (579-648) convinced the Tang emperor Taizong (r. 626-49) that sacrifices offered in a school should be directed to a teacher. Accordingly, Taizong ended sacrifices to the Duke of Zhou and designated Con fucius as First Sage, with the disciple Yan Hui II d? as Correlate and First Teacher (Ouyang 1975, 15:373, 375).11 Taizong extended the cult to lower levels of administration in 630 by requiring every prefectural and county school to build a temple to Confucius, thus creating a systematic network of state-sponsored temples (Ouyang 1975, 15:373). Located inside or adjacent to the government schools, these temples carried out regular sacrifices to Confucius twice a year, in spring and autumn.

Tang ritual codes ranked the sacrifice to Confucius as one of several mid-level rites (zhong), prescribing specific implements, offerings, music, and participants.12 The liturgy imitated that of another mid-level state cult, the worship of the Gods of Soils and Grains (Sheji), which had existed in classical antiquity and whose rituals were prescribed in the Record of Rites (Liji). Because the ceremony for sacrifice to Confucius had no fixed classical form of its own, it was susceptible to innovations, and procedural details often changed. Most significantly, portrait icons were introduced into the ceremony, probably inspired by the images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas in Buddhist temples. Starting in the Tang period, the Chan Buddhist practice of using portrait effigies in memorial rituals for deceased abbots and monks (Foulk and Sharf 1993-94) provided an additional model that encouraged the use of icons in Confucian temples.

0 notes

Photo

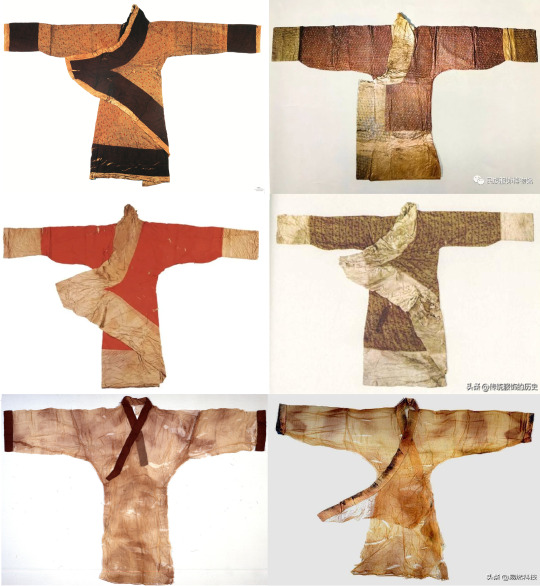

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

China Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE)Female Figurines

Robes (”Quju/曲裾” & Zhiju/直裾”) of silk, cotton and Plain yarn garment(素纱襌衣)from the Mawangdui Tombs belonging to Xin Zhui(辛追), Marquess of Dai - c. 217 BC-168 BC, Western Han Dynasty, China

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE ) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Western Han Dynasty Relics

————————

📸Recreation Work: @吃货娃娃

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/MEFf77xsW

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )#chinese traditional clothing#chinese historical fashion#hanfu history#chinese#chinese culture#Chinese Costume#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#China History#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#historical hairstyles#漢服#汉服#Mawangdui Tombs#Xin Zhui(辛追)#Quju/曲裾#Zhiju/直裾#Plain yarn garment(素纱襌衣)#吃货娃娃

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) was the second dynasty of Imperial China (the era of centralized, dynastic government, 221 BCE - 1912 CE) which established the paradigm for all succeeding dynasties up through 1912 CE. It succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and was followed by the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE).

It was founded by the commoner Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE; throne name: Gaozu r. 202-195 BCE) who worked toward repairing the damage caused by the repressive regime of the Qin through more benevolent laws and care for the people. The dynasty is divided into two periods:

Western Han (also Former Han): 202 BCE - 9 CE

Eastern Han (also Later Han): 25-220 CE

The separation is caused by the rise of the regent Wang Mang (l. 45 BCE - 23 CE) who declared the Han Dynasty finished and established the Xin Dynasty (9-23 CE). Wang's idealistic form of government failed and, after a brief period of turmoil, the Han Dynasty resumed.

Gaozu initially retained the Qin Dynasty's philosophy of Legalism but with less severity. Legalism gave way to Confucianism under the most famous monarch of the Han, Emperor Wu (also given as Wudi, Wuti, Wu the Great, r. 141-87 BCE) who, among his many other impressive achievements, also opened the Silk Road, establishing trade with the West. The Han also negotiated a peace, which was more or less observed, with the nomadic peoples of the Xiongnu and Xianbi to the north and the Xirong to the west which stabilized the borders and encouraged peace and cultural development in the arts and sciences. Many of the commonplace items taken for granted today were invented by the Han such as the wheelbarrow, the compass, the adjustable wrench, seismograph, and paper, to name only a few.

The Han also restored the cultural values of the Zhou Dynasty, which had been discarded by the Qin, encouraged literacy, and the study of history. The historian Sima Qian (l. 145/35-86 BCE) lived during this period whose Records of the Grand Historian set the standard and form for Chinese historical writings up through the 20th century CE. Chinese mythology and religion also developed during this time including the popular messianic movement focused on the Queen Mother of the West.

By c. 130 CE, however, the imperial court had become corrupt with eunuchs exercising more actual power than the Chinese emperor. By the time of the emperor Lingdi (r. 168-189 CE), the Han royal house had less actual authority than the palace eunuchs and the generals (who were more or less autonomous warlords) stationed at the borders of the country. In 184 CE, the Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in response to high taxes and famine and these generals put it down.

Among them was Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE) who, afterwards, waged war against his fellow commanders for control of the state. He was defeated at the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 CE after which the country was divided between three kingdoms and the Han Dynasty fell. Its legacy is so profound that it continues to the present day and the majority of ethnic Chinese refer to themselves as Han People (Han rem) proudly in identifying themselves as descendants of the great ancient dynasty.

#studyblr#history#military history#politics#chinese politics#philosophy#trade#invention#qin dynasty#han dynasty#western han dynasty#eastern han dynasty#xin dynasty#three kingdoms#chu-han contention#yellow turban rebellion#battle of red cliffs#china#emperor gaozu of han#wang mang#emperor wu of han#sima qian#emperor ling of han#cao cao#legalism#confucianism#silk road

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hyperallergic: From a Jade Suit to Bronze Dildos, Ancient Tomb Luxuries of the Han Dynasty Elite

Jade suit, unearthed from Tomb 2, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Nanjing Museum)

Exceedingly wealthy, the royalty of the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) lived indulgently, and these aristocrats were determined to enjoy their accustomed luxuries in the afterlife as well. While their strong affinity for the extravagant is largely unrecorded in historical texts, modern archaeology has immensely helped to shed light on these lifestyles from 2,000 years ago. Since 2009, archaeologists have uncovered thousands of telling treasures buried in royal tombs that date to the Jiangdu kingdom. They found not only exquisite mortuary objects and finely crafted domestic wares but also artifacts that speak to the body’s needs and desires — including a number of ancient sex toys.

Phallus, unearthed from Tomb 1, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Nanjing Museum)

Over 160 of these artifacts from various excavated sites are now on view in Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China’s Han Dynasty, an ongoing exhibition at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. Most of these works have never been seen outside of China; many are rare findings, from a lavish suit with jade tiles sewn with gold thread — actually worn by the deceased — to an elaborate jade coffin painted in lacquer. The hard material was believed to be able to protect the body from decay; jade articles may even have been placed in orifices to prevent the loss of their inner essences.

“The Han, like the Egyptians, also conceived of a soul dualism, or a vital essence, one on earth in the body (po) and one in the ethereal beyond (hun), that could linger on into eternity — even immortality,” co-curator Jay Xu said, “as long as it was properly cared for, and you had the right funerary rites, and regalia and retinue to keep the spirit alive and entertained, and also adequately nourished after death.”

The royal tombs that housed these material splendors were essentially palaces in their own right, comprising sprawling subterranean architectural spaces compete with bedrooms, kitchens, storage areas, and even bathrooms. On view in the museum is a stone toilet — a finely crafted one, and advanced in design, too, featuring stepping stones above a hole for squatting and a rail for support. A vast number of the exhibited tomb artifacts are functional, indicating how they were intended for “use” in the afterlife. Craftsmen, to give another example, also designed one particularly ornate set of bronze bells that chime beautiful notes, meant to guide dance performances that would keep the elite entertained in the afterlife.

Toilet model, unearthed from the Tomb of the King of Chu, Tuolan Mountain, Xuzhou, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Xuzhou Museum)

Urinal (2nd century BCE), unearthed from Tomb 1, Lianying site, Yizheng, Jiangsu, Western Han period (photo © Yizheng Museum)

The Han, as Xu said, “relied on image-making and mystical ornamentation to transfer these possessions into the next world. Think of the tomb itself as a kind of ‘will’ or a registry for the deceased, in addition to the ‘real’ objects.”

These registries were extensive, featuring everything from weaponry to cosmetic box sets to smokeless lamps. On some individuals’s list of wants were bronze objects that may surprise some viewers today, considering how nudity was often considered taboo in traditional Chinese artwork. The exhibition features two bronze dildos that could be both worn and used, sculpted with fine detail. These love aids, according to Xu, were relatively common among elites and were high quality goods, made of expensive bronze. Although considered toys, they were also, as he described, tools.

“When I say ‘tool,’ I also mean that these phalluses had a larger purpose than sheer physical pleasure,” Xu said. “The Han believed that the balance of yin and yang, the female and male spiritual principles, could be achieved during sex. Basically, sex was a pathway to longevity in body and spirit, since these powerful forces could be combined during intercourse to achieve a kind of universal harmony. In this regard, sex, especially if it was pleasurable and lasted for a sufficient amount of time, had a real spiritual dimension.” The small, weighty objects may seem like frivolous inclusions at first glance, but they speak lengths of the Han’s vision of the afterlife as a realm that should promise everlasting happiness and self-love.

Coffin, unearthed from the Tomb of the King of Chu, Shizi Mountain, Xuzhou, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Xuzhou Museum)

Divination board, unearthed from Tomb 10, Lianying site, Yizheng, Jiang-su (photo © Yizheng Museum)

Phallus, unearthed from Tomb 11, Lianying site, Yizheng, Jiangsu. West-ern Han period (2nd century BCE) (photo © Yizheng Museum)

Belt hook in the shape of a rabbit, unearthed from Tomb 9, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu, Western Han period (2nd century BCE) (photo © Nanjing Musuem)

Set of mat weights in the shape of figures listening to music, unearthed from Tomb 1, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Nanjing Museum)

Set of archer figurines, unearthed from the Tomb of the King of Chu, Beidong Mountain, Xuzhou, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Xuzhou Museum)

Bell set, unearthed from Tomb 1, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE (photo © Nanjing Museum)

Lamp in the shape of a deer, unearthed from Tomb 1, Dayun Mountain, Xuyi, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Nanjing Museum)

Pendant in the shape of a cicada, unearthed from the Tomb of the King of Chu, Shizi Mountain, Xuzhou, Jiangsu (2nd century BCE) (photo © Xuzhou Museum)

Installation view of Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China’s Han Dynasty at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (photo courtesy Asian Art Museum)

Installation view of Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China’s Han Dynasty at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (photo courtesy Asian Art Museum)

Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China’s Han Dynasty continues at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (200 Larkin St, San Francisco, CA) through May 28.

The post From a Jade Suit to Bronze Dildos, Ancient Tomb Luxuries of the Han Dynasty Elite appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2odHhlY

via IFTTT

0 notes