#William of Rubruck

Text

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

273 notes

·

View notes

Note

In your opinion, what is female Mongolia like?

If I'm being quite honest? If I were to envision a female Mongolia, I wouldn't make her personality that much different from her male counterpart!

I think I'd give her the name Sarangerel - meaning moonlight (sorry, my goth side is showing but it's also a very pretty name).

The reason why I say this is because often... What I've noticed anyways, is that when people make female Mongolia ocs they tend to hypermasculinise her or use her as a means to insert pretty generic "step on me" girlboss rhetoric onto her. Of course, a female Mongolia would be a strong woman (especially given the history which I explain later in this post) however there is a difference between making her a strong woman and straight up hypermasculinising her. Of course this isn't always the case, I've seen good female Mongolia ocs! However I've seen it too many times considering how obscure Mongolia is as a character anyways, let alone female Mongolia ocs.

When people do this, they usually think they're doing something groundbreaking, but really - they're not. Mongol women and Northern Asian women in general are hypermasculinised along with their male counterparts, lol. It's kind of comparable to how black women are hypermasculinised and the "strong black woman" trope, this time the "strong Mongol woman" trope.

Time to talk about women in Mongol culture!

Mongol women and men back in the day shared a lot of the same chores! Women did bear a greater responsibility with tasks such as cooking, cleaning and child rearing, however it was vital that both men and women were skilled in all aspects of nomadic life. This is because if one parent died, the other parent would then have to fulfil the role of the deceased one. It would be utterly useless if one died and only knew how to do half the chores which are needed for survival on the steppe!

Further, Mongol women had more rights and say in certain things compared to their foreign counterparts. Mongol women were able to become shamans and participate in religious ceremonies, they were able to own and inherit property. They were even allowed to divorce! Their opinions were also valued in court - the wives of higher ranking Mongol men were allowed to give their say. Further, if their husbands were away, sick, or deceased, they could speak on behalf of them.

This is impressive: Mongol women were also responsibile for packing up and setting up camps, making sure all the family's belongings were put safely on a cart, and actually driving the carts - several of them, actually!

They truly were masters of their craft, and their impressive speed at which they could do this was a huge reason as to why Mongol warfare was so light on its feet.

Further, the consumption of alcohol was a vital element in Mongol celebration. Both women and men were free to drink as much as they wished during feasts, and there was no stigma attached to a woman getting drunk.

Accounts from William of Rubruck:

"And all the women sit their horses astraddle like men."

"It is the duty of the women to drive the carts, get the dwellings on and off them, milk the cows, make butter and gruit, and to dress and sew skins, which they do with a thread made of tendons"

"Then they all drink in turn, men and women alike, and at times compete with one another in quaffing in a thoroughly distasteful and greedy fashion" (he wasn't exactly the biggest fan of the Mongols).

Mongol women played in active role in invigorating the Mongol morale. The Secret History of the Mongols details how the wives of rulers would deliver impressive speeches to warriors in order to encourage them to fight diligently.

There are many famous Mongol women, who were known for their intelligence, shrewdness, and strength:

Queen Manduhai:

Manduhai was born into an aristocratic family, and she married Manduul Khan at 18 and had a daughter (not named). After Manduul Khan's death, she adopted Batmunkh, the last descendant of Genghis Khan, and named him Dayan Khan. When Dayan Khan came of age, she married him and became Empress. Despite her experience, Manduhai supported Dayan Khan and played a crucial role in reuniting the Mongol retainers. Remarkably, she fought in battles even while pregnant, enduring injuries and achieving victory. By establishing Dayan Khan as the rightful descendant of Genghis Khan and defeating the Oirats. Manduhai became a legendary figure.

Hoelun (Chinggis Khan's mother):

After her husband, Yesugei, the tribal leader, was poisoned by a rival, Hoelun fled with her son into the wilderness. At the time, Chinggis Khan, who was known as Temujin, was a young child, somewhere between the ages of nine and twelve. Unable to maintain the allegiance of his father's followers, they were abandoned. Nevertheless, despite their ostracised status, the family managed to survive by scavenging and relying on the resources of the land. Hoelun, portrayed as a resilient and determined woman, gathered her children and established a new life for themselves. Her son would later go on to establish one of the most magnificent empires in history. It's even said that Chinggis Khan was only scared of two things, dogs - and his mother's temper!

Khutulun:

Khutulun was known in Mongolia to be an impressive athlete and fighter. She was born in 1260, and was the daughter of Qaidu, and a great granddaughter to Chinggis Khan. During this time, a civil war was brewing amongst the Mongols. Khublai, who later became the emperor of the famous yuan dynasty, was enthusiastic about pushing the empire forward when it came to governing, politics and the likes. Qaidu on the other hand was not impressed by this, and favoured more traditional Mongol values. Qaidu had 14 sons - however it was his one daughter, Khutulun, whom he relied on the most when it came to military expertise.

Marco Polo has this to say about her:

“Sometimes she would quit her father’s side, and make a dash at the host of the enemy, and seize some man thereout, as deftly as a hawk pounces on a bird, and carry him to her father; and this she did many a time.”

Khutulun was a formidable wrestler - and was adamant about not marrying a man unless he could beat her at wrestling. For every match she'd won - she'd be given 100 horses by the loser. It is said she ended up with 10,000 horses.

Did she actually end up with 10,000 horses? It could be somewhat of an exaggeration, as back then 10,000 was a number that was given to mean "a lot", kind of like how we use the word "a million" today. Nevertheless - she was unbeaten.

Her influence is so great in Mongol culture even now. When you look at male Mongolian wrestling outfits - it leaves the chest exposed. This is in reference to Khutulun - to show that the wrestler is indeed, not a woman.

So in conclusion, I personally wouldn't make a female Mongolia's personality that much different to what I envision my male Mongolia's personality to be like, I certainly wouldn't make her more demure by virtue of her being a woman. Mongol society was quite fair to Mongol women anyways, and has been quite consistently egalitarian (I'm definitely not saying things were/are perfect or that it was a feminist paradise, of course). She'd definitely know her worth, and yes, she would be strong - just like her male counterpart.

I also wouldn't want to risk hypermasculinising her because well, as I said before, both Mongol men and women are hypermasculinised (Northern Asian people are in general) and reducing a female Mongolia to a cheap girlboss type doesn't do justice to that character or Mongol history and culture anyways.

#hetalia#aph mongolia#hws mongolia#Hetalia Mongolia#hetalia world stars#hetalia world series#hetalia world twinkle#Mongolia oc#Hetalia headcanon#Hetalia headcanons#Hetalia fandom#Historical hetalia#nyotalia#Aph Asia#Aph east Asia#Hws Asia#Hws east Asia#Nyo Mongolia

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

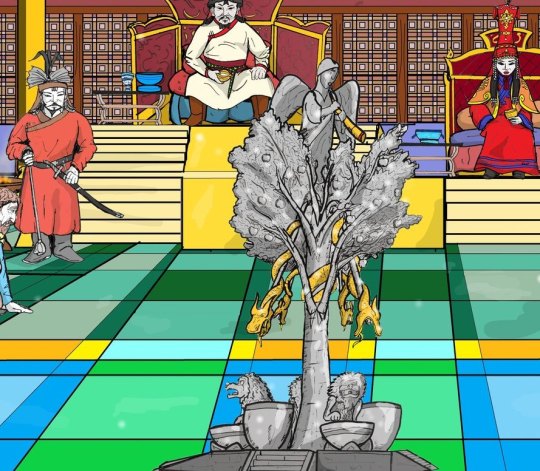

THE THRONE ROOM OF GREAT KHAN MÖNGKE AND THE SILVER TREE OF QARAQORUM

The throne hall of Qaraqorum is one of our best described parts of the entire city. A particularly detailed account comes from the Franciscan Friar William of Rubruck, and mostly corroborated by other contemporaries like Juvaini. All agree in its splendour, and they mostly relate the appearance of the hall during the reign of Möngke (r.1251-1259) who refurbished much of it.

Möngke's throne sat on an elevated position at the northern end of the hall, facing south. His chief wife (Qutuqai Khatun) sat beside some, slightly lower. Three sets of stairs went to them, to which servants walk to bring them meals. To the Khan's left, sat the women of the court; to his right, the men.

Of course, the most famous feature of court is the Silver Tree; Rubruck is the main source for this, but it is alluded to by other sources and similar alcohol "fountains" were features of other Mongol courts (especially Khubilai's). The Silver Tree was a new part of the court; a Parisian goldsmith captured during the invasion of Hungary, William Bouchier, designed and built it (perhaps shortly after Möngke's enthronement). It consisted of a silver-covered trunk with conduits running through it that came out as gilded snakes twisting in the branches; qaraqumiss, bal, grape and rice wines pour from them into containers below. At the base, four lions pour airag/qumiss from their mouths. At the top was an angel, which would blow air through a horn to sound the signal for the drinking to begin.

On the banners behind Möngke, I have also placed his personal seal, his tamga. Finds of his coinage with the seal have been found in Qaraqorum's environs.

You can learn more about Qaraqorum's role in Mongolia's production networks in my latest video on nomadic blacksmithing:

youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's 1:30 in the morning and im going insane because i DO OWN william of rubruck's account of his time in mongolia but it is somewhere in a box 300 kms away from me

#I am normal about everything#I was halfway through the book and i of course didnt take it with me. Anyway#This is a gaming blog. Sometimes you'll get to take a peek on my classicist/history buff past

1 note

·

View note

Text

MARKING THE FACE, CURING THE SOUL?: READING THE DISFIGUREMENT OF WOMEN IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES

“It is taken as read that the sight of a mutilated female face could engender horror and shock in the medieval viewer, and that this generated (and possibly exaggerated) the reports we now have of its occurrence. It was precisely this response that the Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck intended to elicit when he reported his encounter with the wife of the Mongol leader ‘Scacatai’ in 1253.

William commented that: De qua credebam in veritate, quod amputasset sibi nasum inter oculos ut simior esset: nihil enim habebat ibi de naso, et unxerat locum ilium quodam unguento nigro, et etiam supercilia: quod erat turpissimum in oculis nostris. [I was really under the impression that she had amputated the bridge of her nose so as to be more snub-nosed, for she had no trace of a nose here, and she had smeared that spot and her eyebrows as well with some black ointment, which to us looked thoroughly dreadful.]

Elsewhere he deduced from this that such flatness was a marker of beauty within Mongol culture, and that ‘Quæ minus habet de naso pulchrior reputatur. Deturpant etiam turpiter pinguedine facies suas’ [the less nose one has, the more beautiful she is considered, and they disfigure themselves horribly, moreover, by painting their faces]. William’s comments are of course designed to convey to the western European readers of his report – most notably King Louis IX of France to whom he addressed it – the strangeness of his hosts.

Part of the process of ‘othering’ the Mongols was to draw contrasts between their behaviours and those of Westerners, and the appearance and practices of the women, although not strictly a matter with which a Franciscan friar should have been concerned, was just one noticeable difference among many. There is, however, another dimension to William’s sketch of the Mongol women: although he highlights the flatness of their noses as ‘hideous’ and attributes at least one case to deliberate surgery, he does not draw any comparisons about the meaning of this facial feature in his own world.

Yet the bridgeless or flattened nose was commonly thought in the later medieval West to be a sign of leprosy, which itself was associated with dubious morality, whilst a deliberately cut or maimed nose came increasingly to signify a punishment for sexual misdemeanour on the woman’s part. He left it to his readers to make such connections.

The Vita of St Margaret of Hungary (d. 1270), however, provides a striking counterpart to William’s text. For, against the same background of Mongol aggression, this Hungarian princess, given to the Dominican order in childhood, stated that, should the ‘Tartars’ invade Hungary, she would cut off her lips to ensure they found her so repulsive as to leave her unviolated.

Yet her hagiographer relates that when repelling (Western) suitors for her hand in marriage, she declared that she would rather cut off her nose and lips, and gouge out her eyes, than marry any of the three royal suitors proposed. Herein lies the paradox of facial damage for women.

The account of Margaret’s threat of self-mutilation to preserve her virginity against both pagan aggressors and Christian suitors belonged to a long tradition of ‘the heroics of virginity’: St Brigit of Ireland was said to have gouged out her own eye to avoid marriage, whilst one of the most celebrated cases of collective self-mutilation was that of Abbess Ebba and the nuns at Coldingham in England, faced with the prospect of Viking invaders.

Nevertheless the action that Margaret was proposing – which in the context of the approaching pagan Mongols had strong parallels with Ebba’s –would not only leave her open to wound-related infection or even death, but also render her face similar to mutilated criminals, adulterers, pimps and fornicators.

A generation earlier than William’s expedition and Margaret’s vita, legal texts were being promulgated in southern Europe which threatened the slitting of women’s noses (and thus flattening them in grotesque form) for instances of sexual misdemeanours. For example, the laws of Frederick II for Sicily (based on earlier provisions of King Roger II) imposed nose-slitting on adulteresses and mothers who pimped their daughters.

The chronology matters: such a measure had been unknown in western Europe before the eleventh century (although, as we have seen, it was mentioned in earlier Byzantine law). Thus earlier examples of threatened or actual self-mutilation differed starkly from Margaret’s message to her parents: if they forced her to break her monastic vow, they gave her no choice but to carry out an action that would reduce her –irremediably – to the status of marked whore.

The fear of sexual violation, then, drove Margaret’s intention to maim herself, mirroring contemporary legal punishments for sexual and other transgressions. Like most of the cases considered in this chapter, however, it was merely the threat of self-mutilation, rather than its actual practice, that was an effective deterrent. This is a point somewhat overlooked by those convinced that the high and late Middle Ages were a theatre of cruelty.

Moreover, we need to ask how Margaret’s religious commitment, and its subsequent reporting in hagiography, may or may not reflect the secular world. The records we have of actual judicial processes often stop at a court’s verdict – the sentence of mutilation, rather than its actual execution – and women form a very small minority of those so sentenced. In fact, cases of women actually being judicially mutilated are quite rare, and not all examples were for cases of immorality.

Helen Carrel has argued that ‘The threat of harsh punishment, which was then ultimately remitted, was a set piece of medieval legal practice’, and suggests that, although mutilation was prescribed for many offences, it was rarely put into practice after the late thirteenth century. Margaret’s threat, therefore, might be understood as just that – its extremity designed to convey her deep-seated religious commitment through the idea of radical, physical self-harm, invoking an image in the reader’s mind but not carried out in practice.

Elsewhere in the secular world, the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century German and Swiss urban records studied by Groebner reveal definitive evidence of actual facial mutilation taking place, but the targeting of the face of suspected or actual adulterers outlasted formal, juridical ‘mirror punishments’ by the authorities by the fifteenth century, and seems to have been an extreme, and unsanctioned, act of anger carried out on the face of a spouse suspected of adultery, or her/his lover, or even on the innocent partner of the lover.

Such ‘private’ attacks, Groebner suggests, were still driven by the association of adultery with facial punishment, but these incidents make it into the records so that the attackers might be censured (somewhat lightly, given the injuries they inflicted). This unofficial understanding of violent, facial punishment against women for their perceived lapses may already have been an accepted social norm in other regions by the thirteenth century.

Again, evidence comes from the records of proceedings against the perpetrator of the violence. A hearing before the podestà’s court in Venice in May 1291 centred on the assault of Bertholota Paduano of Torcello by a priest from the island of Burano. Bertholota testified that when she defended her friend Maria against the priest’s slanderous words: et percussit dictam Bertholotam sub oculo sinistro cum digito, et postea cum pugno bis per caput, scilicet semel per vultum iuxta nasum, talieter quod sanguis exivit ei per buccam et per nasum et alia vice iuxta aurem, et postea iniuravit ei dicens, ‘Turpis vilis meretrix, nunc aliquantulum feci vincdictam [sic] de te, vade acceptum bastardos quos fecisti de Valentio, quia sum dolens et tristis quod non proieci ipsam in aquam’.

[The above parish priest raised his hand and hit the above Bertholota with his hand below her left eye, and then twice with his fist on her head: that is, on her face by her nose, so that blood began to flow from her mouth and nose, and another way by her ear, and afterwards he injured her, saying: ‘You shameful and vile whore, now I have given you a little punishment [my emphasis], go, and take the bastards you had by Valentio with you, for I am grieving and sad that I did not throw her [Maria] in the water.’]

Further witnesses added that they heard the priest say, ‘Illa turpis meretrix; modo feci quod cupivi et, nisi fuisset pro presbitero qui eam defensavit, male apparassem eam.’ [‘She is a filthy whore; now I have done what I wanted to do, and had it not been for the priest who defended her, it would have gone badly for her.’] We do not know how this case ended – presumably the clerical perpetrator of the assault would have objected to being hauled up before the secular podestà’s court and the case may well have been referred to his clerical superiors, which would explain the lack of sentencing as it survives in the podestà’s records.

What the hearing did to Bertholota’s reputation is also unknown, but the record is revealing in how it presents the case, and what it chooses to include. Arguably, the victim’s physical appearance after the attack (temporarily bloodied face and black eyes, and more permanently a probable broken nose) would have raised questions about her status as a respectable woman, but it is striking that she is named in the record whilst her assailant is not, and that her reputation as a whore was rehearsed in court (twice) and then written down.

The case itself may therefore have been more punitive on her than on him, and this may have been the latter’s intention. He was, after all, a priest, and may well have considered himself within his rights to challenge Bertholota’s (and Maria’s, for that matter) way of conducting their lives, particularly if Bertholota’s children had been born out of wedlock as the record suggests. But it is clear that there was a distinction to be drawn between legally-sanctioned punishment, controlled by the Venetian state, and the violence occasioned by this individual’s sense of outrage against the women.

Religion is present here of course – the assailant was a priest – but his actions were hardly designed to bring Bertholota to repentance. The theme of the punished fornicator brings us to our second holy woman, in the form of St Margaret of Cortona. Her lengthy vita, consisting almost entirely of Margaret’s dialogues with Christ (and thus effectively positioning her in a face-to-face relationship with him), centres on Margaret’s remorse at her previous life of sexual freedom that had resulted in her bearing an illegitimate child.

Margaret was apparently strikingly beautiful, and the motif of denying this beauty recurs throughout the life, as she struggles ever closer to her true love, Christ himself. Early in the life Christ says: ‘Recordare, quod tui aspectus decorem, quem hactenus in mei magnam injuriam conservare conata es, imo et augere, adeo abhorrere et odire coepisti, ut nunc abstinentia, nunc lapidis allisione, nunc pulveris ollarum appositione, nunc diminutione frequenti sanguinis, delere desiderasti.’

[‘Remember how you previously endeavoured to maintain and even increase your beautiful appearance, much to my injury, and now you have begun to abhor and hate it, so that now you desire to rub it out with fasting, by dashing your skin with stones, by covering it with dust, and by frequent bleeding.’]

But such trials are not yet enough – when Margaret asks Christ to call her ‘daughter’, he replies rather tersely, ‘Non adhuc vocaberis filia, quia filia peccati es; cum vero a tuis vitiis integraliter per generalem confessionem iterum purgata fueris, te inter filias numerabo’ [‘You won’t be called daughter yet, for you are the daughter of sin. Only when you are completely purged of your vices by constant confession, then I will count you among my daughters.’].

This handily reminds us that Margaret had to overcome not only her past life, but her very status as woman, as a daughter of Eve, whose original sin marked her with a sexuality that fasting, scarification and the denial of bodily comforts could only control, not destroy. Margaret’s request to become a recluse is also refused, by God, who has other plans for her.

The vita was written by Margaret’s confessor, and he has a major role to play as she becomes increasingly frustrated by her failure to achieve her goal. Seeing that her abstinence is not destroying the beauty of her face fast enough, she secretly hides a razor and asks her confessor’s permission to use it to cut off her nose and top lip, for ‘Et merito, inquit, hoc vigilanter desidero, quia vultus mea decor multorum animas vulneravit’ [‘I deserve it and strongly wish it, since the beauty of my face has injured the souls of many’].

But he refuses permission, and threatens not to hear her confession again if she carries out her intent. Margaret’s later request to Christ, to afflict her with leprosy, meets a similar refusal. If she wanted to reach Christ, the message appears to be that she had to do it the hard way, not by quick solutions such as enclosure, self-harm or disease.”

- Patricia Skinner, Medicine, Religion, and Gender in Medieval Culture

#cw: racism#cw: self harm#beauty#gender#religion#medieval#christian#patricia skinner#medicine religion and gender in medieval culture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

books i might wanna read when i don’t have 67123576512 other things to read or whatever if you’re curious you can just google the titles because i didn’t save all the info in my notes app

Voices from the Chinese Century: Public Intellectual Debate from Contemporary China

The Crooning Wind: Three Greenlandic Poets

Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys

Crude Chronicles: Indigenous Politics, Multinational Oil, and Neoliberalism in Ecuador

In the Shadow of Islam

The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution

Seeing Like a State

White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism

Memory and the Mediterranean

Losing Earth: A Recent History

Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor

Karlamagnús Saga: The Saga of Charlemagne and his Heroes

The Sinner and the Saint: Dostoevsky and the Gentleman Murderer Who Inspired a Masterpiece

Icebound: Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World

Panpsychism in the West

Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System

Marx's Ecology: Materialism and Nature

The Savage Frontier: The Pyrenees in History and the Imagination

Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders

Babur Nama: Journal of the Emperor Babur

The Singer of Tales by Albert Bates Lord

Slavery and Empire in Central Asia

The Adventures of Sayf Ben Dhi Yazan: An Arab Folk Epic

The Travels of Ibn Battutah

I Burn Paris by Bruno Jasieński

The Book of Dede Korkut

The knight in the Panter’s SkinTravels with Herodotus by Ryszard Kapuściński

Deep Sea and Foreign Going

Big Dead Place: Inside the Strange and Menacing World of Antarctica

The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars

The Journey Of William Of Rubruck To The Eastern Parts Of The World

Recollections of Tartar Steppes and Their Inhabitants

The Expedition of Cyrus by Xenophon

Xenophon's Retreat: Greece, Persia, and the End of the Golden Age

From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire

The Gobi Desert - The Adventures of Three Women Travelling Across the Gobi Desert in the 1920s

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

Forbidden Journey by Ella Maillart

The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code

The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett III: Multiple Universes, Mutual Assured Destruction, and the Meltdown of a Nuclear Family

Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe

The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South

No Less Than Mystic: A History of Lenin and the Russian Revolution for a 21st-Century Left

Philosophy and Real Politics

Writing East: The "Travels" of Sir John Mandeville

Poetry of the Taliban

Cabool by Alexander Burnes

Warrior Saints of the Silk Road |

The Place of the Skull by Chingiz Aitmatov

Starship & the Canoe

Nauru Burning

Our Women on the Ground: Essays by Arab Women Reporting from the Arab World

Death Is Hard Work

The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics

A Grain of Wheat

Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming

Annals of the Former World

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ

The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Write a paper on “The travels of Abu Hamid” and “The Journey of William of Rubruck Post navigation

0 notes

Text

(Answered) How do Muslims and Christians in the Medieval period view the world?

(Answered) How do Muslims and Christians in the Medieval period view the world?

(Answered) How do Muslims and Christians in the Medieval period view the world?

You have read The Quran, The Voyages of Ibn Battuta, William of Rubruck’s account of the Mongols,and Sundiata, for this paper. Three of these are composed by Muslims and one is composed by Christians. Based on these three sources, how do Muslims and Christians in the Medieval period view the world? Are they more…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Online medieval manuscripts / books

I compiled this list a few years ago and decided to repost is. Short of Corona reading list ;-). I’ve also checked the links so they should work-

* Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (pdf)

* A scholar and his cat Pangur Bán - 9th centyry Irish poem

* Bede: Ecclesisastical History of England

* Belisarios’ letter to Totila

* Codex Manesse (German / original, pdf)

* Geoffrey de Villehardouin: Chronicle of the Fourth Crusade and The Conquest of Constantinople

* Gregory of Tours: History of the Franks

* Isidore of Seville: Etymilogiae

* Itinerary of Benjamin Tudela (pdf)

* Jordanes: The Origin And Deeds of the Goths

* Paul the Deacon: History of Langobards

* Procopius of Caesarea: The Secret History (html)

* Procopius of Caesarea: History of Wars Books I-II (Persian Wars)

* Procopius of Caesarea: History of Wars Books V-VI (Gothic Wars)

* The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

* The Journey of Friar John of Pian de Carpine to the Court of Kuyuk Khan, 1245-47

* Travel Books of Ibn Hattuta

* William of Apulia: The Deeds of Robert Guiscard

* William of Rubruck’s Account of the Mongols (1253-55)

255 notes

·

View notes

Note

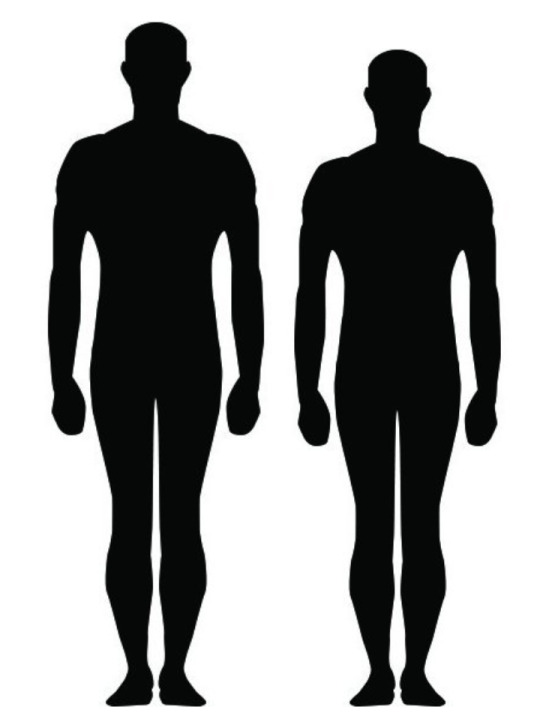

How tall do you think Mongolia is?? I always imagine him to be pretty tall. but short Mongolia is precious 😳

Brillant question cause it let's me rant a bit about Mongol appearance!

The typical artist draws Mongol warriors like this:

Notice the stocky build? Still he looks super intimidating, so clearly this guy is like 5'10" right?

Not according to the people who recorded the mongolian appearance.

From Frank McLynn's Genghis Khan (my favorite Mongolia book atm) we have these cited descriptions of Mongols:

- Frair Caprini, a European vistor, described Mongols as "...usually short of stature and slim..."

- William of Rubruck (another European visitor) states "...and almost all are of medium height."

A Christian Armenian (with probably a big bias against the Mongols) writes, "...[they had] short legs like a hog's..."

Most of the books I've read establishes this--that Mongol males were short but stocky--as commonplace, and that trend continues today.

Modern Mongolia is made of mostly the same people, and the trend of Mongolian men being relatively short people continues compared to the 5'9" American average. The average Mongolian male is 168.4 centimeters tall, or 5'6.5", which is noticeably less than 5'9"

Left: Typical male at 5'9"

Right: Mongolian male at 5'6.5"

So yeah, my theory is that Mongolia is shorter than average throughout his life and thus height differences are VALID, thanks for asking!

#mongolian#aph mongolia#mongolian height#history#sassy's stash#but yeah totally rec mclynns book its great#mongolia is SHORT and I have a thesis to PROVE IT#listen to me ramble sksksn#kayalbow#ask#written answer

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

My characters: The Antiquated Scholar (The Silver Tree)

Known as: The Antiquated Scholar | William of Rubruck | Willem van Rubroeck | The Widow’s Appraiser

Addressed as: Sir. Pronouns: He/Him.

Character Masterpost

Note: William of Rubruck was an actual historical person, who you play as in Silver Tree. This is developing what happens to him in my head after the ending of the game.

The Antiquated Scholar is quite a strange sight around London, that is if you see him at all. He is employed as an appraiser by the Gracious Widow. And since you never see her face, who you’ll meet with if an in-person meeting is required. Since the Widow allows him to go behind her curtain, she obviously trusts him greatly. What is his accent? Dutch? French? Some zailors swear it sounds Khanatian. There is something about how he speaks English that sounds...off. Not to mention that fur coat and how uncomfortable he looks in a suit. He takes his notes in Latin of all things. Various priests will swear that he’s Catholic.

In truth, the Widow’s Appraiser is William of Rubruck, the Flemish monk sent by King Louis IX and the Pope to the Mongolian capital of Karakorum. He was supposed to assess their military capabilities and try to convert them. In reality, he came to feel more loyalty toward the Mongolian Kahn than his own religion. He was there when Karakorum fell in 1254. His bond with the Princess only grew. As he got to drink her peach brandy as well, William has remained the Widow’s partner throughout the centuries. In London, he assesses any unique objects that make their way into the Widow’s ring. He also deals with people in person so that the Widow doesn’t have to reveal she’s Mongolian.

His inquisitive nature has rendered him probably the single human (key word human) most knowledgeable about the secrets of the Neath. He’s also become a common sight at the University, using their libraries to update himself on Surface history and science.

As for his religion, he’s still Catholic (1400s Catholic to be precise), in a sense. He turned away from the dogma of the Church when he saw Parabola with his own eyes. But not just that. He saw in Karakorum that he’s “barbarians” had more tolerance- more love for the strangers inside their own land- than his own people. His own beliefs are a mixture of Catholicism, Neath-Tengrism (it’s very location dependent. Their head god is literally the Great Blue Sky, which has been replaced by Storm. Some of the entities are real, other are not), and his own observations. It functions inside the framework of Tengrism, which allows multiple gods to coexist very easily. The deities are also not inherently good. You worship them when needed to gain their boons. In his mind, the general gist of the Christian god is real, it's just that His influence is limited to the Surface. He created the world and the Neath is the equivalent of the back of the canvas. And with that, William accidentally figured out how Judgments work.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guillaume Boucher and the Fountain of Karakorum

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan, A stately pleasure dome decree, Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man, Down to a sunless sea. Coleridge did not mention their incredible drinks dispenser....

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea –

Samuel Taylor Coleridge- Kubla Khan (1816)

Hi folks, today’s tale- Like Coleridge’s Kubla Khan- is a fragment. Like Coleridge’s poem it concerns the Mongol Empire, at a time when one of the great Genghis Khan’s grandsons ran the show. Unlike Mr…

View On WordPress

#13th Century#Andrew of Longjumeau#Baibars#Genghis Khan#Guillaume Boucher#Kublai Khan#Mongke Khan#Mongol Empire#Ong Khan#Samuel Taylor Coleridge#Tengriism#Tree of Karakorum#William of Rubruck

0 notes

Text

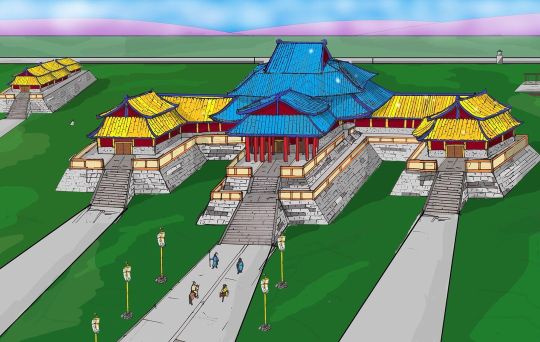

THE GREAT KHAN'S PALACE AT QARAQORUM

In Qaraqorum, the Mongol Imperial capital from the 1230s-60s, the Great Khan held his residence twice a year. First built by Ögedei Khan, and refurbished by Möngke, it was in a "Forbidden city," to the south of the main city of Qaraqorum, a separate, walled-off section which had numerous secondary structures and palaces for other members of the Altan Urag and their servants. The structure was known was the Qarshi to the Mongols (palace) and also by a Chinese name given to it, the Wanangong, Palace of Eternal Peace.

The Qarshi of Qaraqorum/Erdene Zuu monastery is the sqaure at the bottom of this topopgraphic map of the site

While the Qarshi is no longer extant, we have a fairly good understanding of its position and layout thanks to the numerous references and descriptions of it in Chinese, European and Islamic accounts, and comparisons to the sites of other 13th century Chinggisid palaces (like Kondui palace).

The Qarshi consisted of a central, main hall (often singled out in sources for its magnificence and height), flanked by two smaller halls ("naves", in William of Rubruck's eye-witness description, who compared the entire structure to a church). It was built by Chinese craftsmen and this layout matches certain Chinese palace designs, though modified for Chinggisid tastes. In the Orkhon Valley, Siberian larch along with local granite quarries were use in the city, and must have featured extensively on the palace. Labourers were brought in to make dried-bricks and kilns for roof tiles on-site for most of the rest of the construction.

With the abandonment of the city by the fifteenth century, the Qarshi fell into disrepair. By the late 1500s, the Erdene Zuu monastery, was constructed on the site of the palace, likely reusing what remained of usable building material. While Erdene Zuu differs in layout, it likely offers a clue to the orientation of the earlier structure

You can learn more about Qaraqorum's role in Mongolia's production networks in my latest video on nomadic blacksmithing:

youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The deadly irony of gunpowder - Eric Rosado

TED-Ed

View full lesson: http://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-deadly-...

In the mid-ninth century, Chinese chemists, hard at work on an immortality potion, instead invented gunpowder. They soon found that this highly inflammable powder was far from an elixir of life -- they put it to use in bombs against Mongol invaders, and the rest was history. Eric Rosado details how gunpowder has caused devastation around the world, despite the incandescent beauty of fireworks.

#gunpowder#ancient china#china#chinese#guns#fireworks#ancient history#history#ted-ed#ted talks#ted#eric rosado#chinese history#ancient mongolia#mongolia#mongol#william of rubruck#1254#1200s#13th century#medieval europe#medieval#europe#european#cannons#bombs#videos

0 notes

Text

also I’m reminded of when the Franciscan monk William of Rubruck travelled to the court of Möngke Khan and while there participated in a great religious debate organized by the cosmopolitan-minded Möngke and how over the course of it the topic settled on Monotheism vs Polytheism with Muslims (probably of varying sects and schools), Nestorian Christians and William’s Catholic entourage championing the former and scholars of Vajrayana, Mahayana, Confucian and Taoist backgrounds defending the integrity of polytheism with William saying he eventually became the champion of the Monotheists (William would obviously have a bias to say something like this but his background was that of a lawyer so its fully possible he was found to have the best debate skills) and his opponent being probably being a Taoist monk named Changchun (this is scholarly conjecture based on context clues bc William didnt know what Taoism was and seemed to think he was arguing with Manichaeans) and I’m wondering if his compatriots were ever like “please dont tell them about the Trinity please dont I get that you think you can have it make sense in Latin but for the love of everything do not mention that you think God necessarily is three persons that will be such good ammo for their side”

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

i wanna do themed leisure reading months...... .... thinking of pairing old travelogues by women (dated up to 1930 max) + REALLY old travel acct + non-fiction about the same region + first person native story of same region. would be fun.

example;

Recollections of Tartar Steppes and Their Inhabitants (1863)

+

The Journey Of William Of Rubruck To The Eastern Parts Of The World ( William of Rubruck (circa 1220 - 1293))

+ Odgerel (starlight ) 1957 Sonomyn Udval.

+ Beyond Great Walls: Environment, Identity, and Development on the Chinese Grasslands of Inner Mongolia - Dee Mack Williams

Maybe.

1 note

·

View note