#Yangshao

Text

We do not know where this jar was excavated, but it has a distinctive shape matching many found at one of the most famous sites of #Yangshaoculture, called Banpo. Banpo gave archaeologists a picture of how peop

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A red pottery bowl with fine pricked designs

Yangshao culture, Banpo phase, c. 4800-4300 B.C.

D. 19.2 cm

#A red pottery bowl with fine pricked designs#Yangshao culture Banpo phase c. 4800-4300 B.C.#pottery#ancient pottery#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Pottery#China 🇨🇳#Eagle 🦅 Shaped Tripod#National Museum of China 🇨🇳 | Beijing#Yangshao Culture | Neolithic Era | 6000 Years Ago

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today's obsession: 6000 year old eagle-shaped pottery ding from Yangshao Neolithic Culture.

Look at it.

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 13, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi Archaeology Museum/陕西考古博物馆 (Part 1 - Neolithic to pre-Qin dynasty):

Unfortunately I was not able to acquire tickets to the Shaanxi History Museum/陕西历史博物馆, which is one of my biggest regrets from this entire trip, because Shaanxi History Museum is the provincial-level museum, it has a lot more artifacts. Xi’an is the capital city of Shaanxi Province, so it has both the city-level museum and the provincial-level museum; the one I posted about previously, Xi’an museum, is just the city-level museum.

But fortunately Xi’an has a quite a few history museums, which makes sense considering the city’s very long history, so on we go to the Shaanxi Archaeology Museum:

For the longest time I also thought archaeology was a very European thing, but actually? It did also exist in ancient China. The word guxue/古学 (lit. “Antiquity Studies”) existed as early as Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD), and by Song dynasty (960 - 1279 AD), kaoguxue/考古学/archaeology was pretty well known. Sidenote: the word 考古学 may not mean exactly the same thing as archaeology in Song dynasty, but today it just means archaeology. Below is the Song-era kaoguxue work named 《考古图》 (this book on display was printed in Qing dynasty, judging by the cover):

Compare the above with the notes of a modern archaeologist:

A collection of interesting Neolithic era pottery artifacts with various faces on them. Some are from Yangshao culture/仰韶文化 (5000 - 2700 BC). I swear you can make reaction pics out of these lol

They even have these refrigerator magnet souvenirs lol

Is that a pottery piggy on the right? This piggy looks oddly familiar…

Which reminds me of this other pottery pig found near the Sanxingdui/三星堆 site (Picture from Douyin user 姜丝炒土豆丝). Looks very familiar indeed lol

A pottery drum reminiscent of an udu drum. The one in the front is a replica that visitors can try out

Left: a pottery artifact with a frog face on it. Right: a pottery tiger I think? Not sure.

Shang dynasty (1600 - 1046 BC) jade dragon:

Carved stone bricks from the neolithic site of Shimao/石峁 (~2000 BC). These were originally found in the outer walls of the site, which is why they are presented this way:

Mouth harp artifacts from Shimao culture (top one is a modern one, for comparison). There’s also a map on the many variations of mouth harps from cultures around the world, which is really cool:

Fragments of bone flutes. These were flutes fashioned from crane bones, the most famous of which were the intact flutes unearthed from the Jiahu/贾湖 site dating back to 7000 - 5700 BC, and they were still playable (first link is the 1999 Nature article regarding this discovery, second link goes to a recording of a modern musician playing the song 小白菜 on one of these bone flutes)

A Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BC) bone hairpin. There were quite a few hairpins in the exhibition, but this is my fav:

And now comes the really cool stuff: oracle/divination bones. Oracle/divination bones were animal bones that ancient Chinese people (mostly of Shang-era) used for divination. These bones have holes drilled into them in a pattern and have oracle bone script/jiaguwen/甲骨文 carved into them (the carved text consists of questions presented to the gods), and then they were heated slowly over a fire until the bone starts to crack. A priest or priestess would then interpret these cracks, as they were seen as answers from the gods, and record the answer on the bone. Sometimes these bones were used purely as records for important events:

Since oracle bone script is the oldest form of Chinese written language, it is possible to decipher the text carved onto these bones:

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi archaeology museum#chinese history#chinese culture#ancient history#chinese language#archaeology#oracle bone#oracle bone script#history#culture

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 51: Early Modernish and Earlier

These Questions are the result of suggestions a the previous iteration. This category may include suggestions made too late to fall into the correct earlier time grouping. In some cases a culture lasted a really long time and I grouped them by whether it was likely the later or earlier grouping made the most sense with the information I had.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration. All cultures and time periods welcome.

#Time Travel#Early Modernish#Émilie du Châtelet#French History#Madame de Sévigné#Marquis of Montespan#Versailles#Mme de Rambouillet#Blue Room of Mme de Rambouillet#Saint-Lambert#The Marquis du Châtelet#Catherine Montvoisin#La Grande Mademoiselle#Orléans#the Fronde#Louis XIV#Henri II#Diane de Poitiers#Henri II of France#Robert Dudley#Earl of Leicester#Queen Elizabeth#Kenilworth#Château de Chantilly#François Vatel#The Pleasures of the Enchanted Isle Party#Louise de la Vallière#Neolithic#Chinese History#Cahokia

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Gallery of Chinese Art & Architecture

Chinese culture developed from small communities such as Banpo Village (c. 4500 BCE) through the early Xia Dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BCE) and the great dynastic periods that followed after, creating some of the most striking and memorable works of art and architecture in world history, including the famous Great Wall of China.

These works include palaces, towers, walls, paintings, sculpture, amulets, coinage, and ceramics – some dating back as far as the Houli Culture (c. 6500 - c. 5500 BCE) or earlier – others from the periods of the Liangzhu Culture, Yangshao Culture, and Hongshan Culture, predating the Xia Dynasty and its successor the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) by which time Chinese work in jade, especially, had produced notable masterpieces such as The Correya Dog.

The following gallery is far from inclusive but presents representative pieces from the earliest eras of ancient China up through the modern day.

Continue reading...

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Stuff #13: Cats in China--History (Part 1)

(Warning: Very long post ahead with multiple pictures!)

(Link to Part 2)

Since this topic is pretty big, I will split the content across 4 posts, but even then these posts will only be a shallow summary of the subject.

This small series of posts is dedicated to my fluffy quadrupedal friend, 小葱 (Little Green Onion).

-------------------------------------------------

Did you know that there are over 200 cats in the Palace Museum/故宫博物院 in Beijing? Some of these cats were descendants of the pet cats of the imperial family hundreds of years ago, and some of these cats were simply strays, but they all found a home in the Palace Museum, and are now being fed and taken care of by the museum employees. You may even catch a glimpse of one of these cats during a visit to the museum.

Here are two of these cats, Jixiang/吉祥 (right; name means “auspicious”) and Ruyi/如意 (left; name means “(may things go) according to (one’s) wishes”)

Speaking of the Old Palace and royal kitties, cats actually have a fairly long history of being mousers and human companions in China, and sometimes they were even seen as powerful spirits to be both worshipped and feared.

Cats As Guardian Spirits

According to archaeological evidence, in China, cats came into people’s lives as early as 5300 years ago (~3300 BC). People of the Neolithic Yangshao Culture/仰韶文化 (~5000 - 3000 BC) in what is now central China grew millet, rice, and vegetables. These crops were bound to attract small rodents like mice and rats to human villages, which attracted wild cats in turn. There were no evidence showing that these wild cats had any sort of special or intimate bond with humans yet, so the relationship was likely a simple mutualistic relationship in which cats benefitted from having a steady source of prey, while humans benefitted from having their harvest protected from rodents. In the Book of Rites/《禮記》, a book detailing Zhou dynasty (1046 - 256 BC) etiquettes, administration, and ceremonial rites, there was a passage on the religious aspect of this mutualistic relationship:

“The wise and gentle rulers of yore will always repay the good deeds that others have done for them. Welcome the cats, for they are hunters of mice; welcome the tigers, for they are hunters of boars; welcome them and worship them”. (“古之君子,使之必報之。迎貓,為其食田鼠也;迎虎,為其食田豕也,迎而祭之也 。”)

-- Book of Rites, The Great Suburban Sacrificial Rites chapter (《禮記·郊特牲》).

As we can see in this short passage, people in ancient China regarded cats as spiritual beings--one of eight important animal spirits worshipped in the great ritual at the end of the year that must be performed by the ruler--and made offerings to them as a way to thank them for controlling rodent populations in the fields and protecting the year’s harvest.

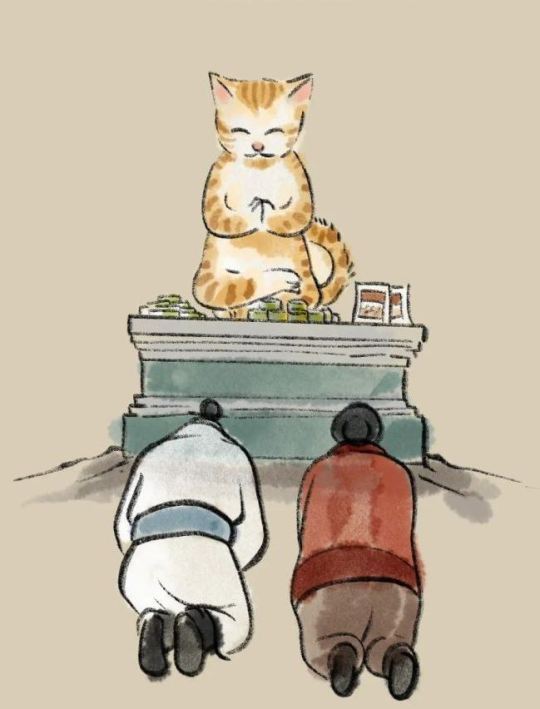

^ Illustration by 国馆 on Zhihu.

Cats as Evil Ghosts

In ancient folk belief, however, cats eventually became associated with wugu/巫蛊, which can be generally understood as “witchcraft” or “black magic”. Practitioners would sacrifice cats and keep “cat ghosts”/猫鬼, then send them out to curse whoever they wish to harm and steal money from. There was one famous case of this during Sui dynasty (581 - 618 AD) that was recorded in Book of Sui /《隋書》, the traditional official historical records of Sui dynasty that was completed in 636 AD. As the chapter “Consort Kin” (《隋書·外戚》) described, when Empress Dugu and Head of Secretariat Yang Su’s wife fell ill, the doctors diagnosed their illnesses as “caused by cat ghosts”. Emperor Wen of Sui/隋文帝 (personal name Yang Jian/楊堅) assumed that Dugu Tuo/獨孤陀 was behind the mysterious illnesses since Dugu Tuo was the paternal half-brother of Empress Dugu and his wife was the paternal half-sister of Yang Su, but Dugu Tuo denied having anything to do with it. So his household was questioned, and finally one of his housemaids confessed to be a practitioner of “witchcraft” and that she had cursed Empress Dugu and Yang Su’s family with her cat ghost under orders from Dugu Tuo. Dugu Tuo was stripped of all his titles along with his wife, and both were demoted to commoner status. So as we can see it was big enough in folk belief that it actually made its way into some imperial family drama. After this event, Emperor Wen of Sui declared a ban on these practices that were meant to cause harm to others.

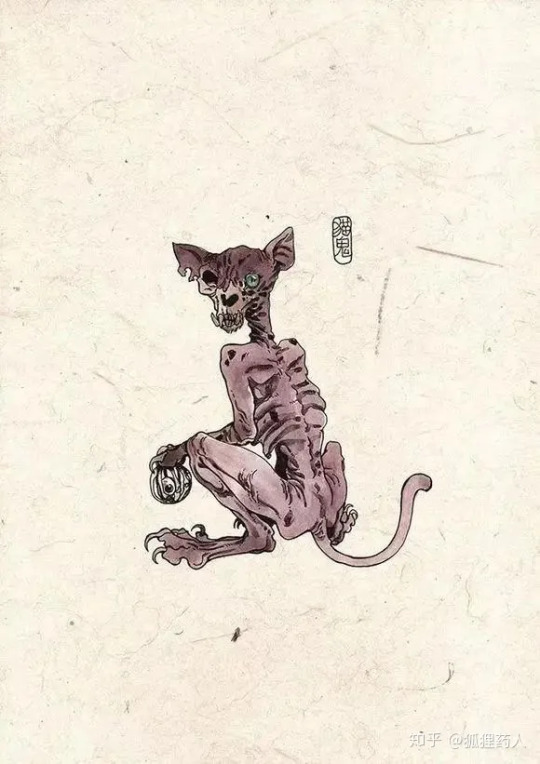

^ A modern illustration of a “Cat ghost”, from the work titled Hundred Ghosts of China/《中国百鬼录》.

Cats in Analogies and Folklore

Cats have also been used in the classic cat-and-mouse analogies in different situations. During Wu Zetian/武則天’s ascent to power in Tang dynasty in 655 AD, she was involved in a power struggle with Empress Wang and Consort Xiao, and after some back-and-forths, Empress Wang and Consort Xiao were demoted to commoner status and imprisoned. Consort Xiao then cursed Wu Zetian, saying:

“May you become a mouse and I a cat, so I can choke you!” (”願阿武為老鼠,吾作貓兒,生生扼其喉!”)

-- Old Book of Tang, ”Empresses and Consorts Part 1”/《舊唐書· 后妃上》

Apparently after this happened, Wu Zetian banned cats from the palace out of fear.

Another example of this cat-and-mouse analogy was the memorial Su Shi/蘇軾 submitted to Emperor Shenzong of Song/宋神宗 (personal name Zhao Xu/趙頊) that argued against the parts of the reform proposed by Wang Anshi/王安石. This memorial was preserved and later named《上神宗皇帝書》. In it, Su Shi argued that government officials must be able to freely object another official’s proposal in order to prevent treacherous officials from gaining too much power with this analogy:

“We keep cats in order to keep mice at bay, but we cannot keep cats who can’t catch mice just because there are no mice around; we keep dogs in order to keep burglars away from our homes, but we cannot keep dogs that don’t bark just because there are no burglars around”. (”然而養貓所以去鼠,不可以無鼠而養不捕之貓。畜狗所以防奸,不可以無奸而畜不吠之狗”)

There weren’t only cat-and-mouse analogies, however. There's a short fable about cats and tigers that was passed down through the generations from at least Song dynasty all the way to the present day. Even I have heard of this story as a child. In this fable, the tiger was initially very clumsy, so the tiger asked a cat to teach it how to hunt. The cat agreed and taught the tiger how to track down, stalk, pounce, and play with prey, but refrained from teaching the tiger about tree-climbing. The tiger eventually mastered the art of hunting, and one day the tiger turned on its teacher, the cat, who then climbed atop a tree to save its own life. The moral of the story was either “never teach others everything you know, in case they use your knowledge against you”, or “never teach those who are ungrateful”, which resulted in the xiehouyu/歇后语 (a type of Chinese proverb) “cat teaching the tiger -- withhold some of your abilities” (“猫教老虎--留一手”). Of course, this fable doesn’t really stand in terms of scientific accuracy, seeing as tigers are proficient tree-climbers themselves, but the fable itself is still very interesting nonetheless. Although the origin of this fable has now faded into obscurity, the earliest record I could find was from the self-annotation on the poem “Mocking the Cats”/《嘲畜貓》 by the famous Song-era poet Lu You/陸游 in 1198 AD, which showed that this fable was already popular in folk culture in Southern Song dynasty:

“In folk belief cats were the uncles of tigers, they taught the tigers everything except how to climb trees”. (“俗言貓為虎舅,教虎百為惟不教上樹”)

^ Modern illustration of the fable, from children’s book The Tiger and the Cat by Eitaro Oshima.

Historical texts showed that at least from Southern and Northern dynasties (420 - 589 AD) and on, most people kept cats for their ability to catch mice, and oftentimes keeping cats as just house pets was something that was still limited to royalty, nobility, and rich people. But as we would see in Part 2, there were evidence from Song dynasty that showed a definite change in how cats were viewed in the ordinary household.

(Part 2 Here!)

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

6000 years ago, the more intrepid farmers of the Yangshao Culture ventured west, eventually settling atop a vast plateau where life is harsh and a nearer sun beats upon frostbitten skin. They looked down on the cozier existence of their brethren who remained in the lowlands. Thus you have the origin of all conflict between Tibetans and the Han

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

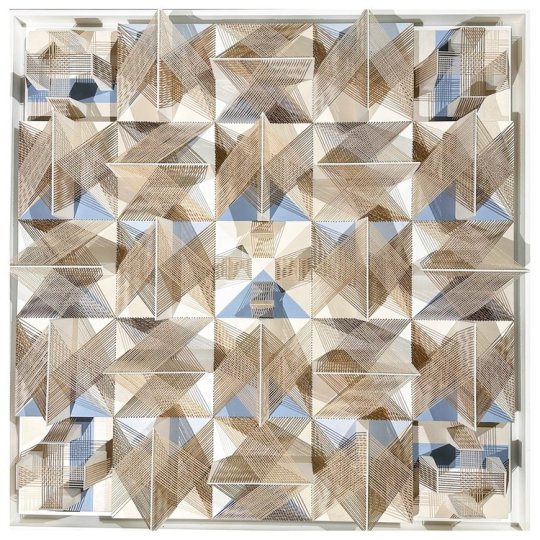

Nessim Bassan. First Mechanism Used To Make Silk in Yangshao Culture, 2023.

cotton threads, acrylic + wood on canvas

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

USGS map of copper distribution

Chalcolithic - The Copper Age or Eneolithic

Africa (2600 BCE - 1600 AD)

West Asia (6000-3500 BCE)

Europe (5500-2200 BCE)

Central Asia (3700-1700 BCE)

South Asia (4300-1800 BCE)

China (5800-2900 BCE)

Mesoamerica (5000-2900 BCE)

Central Asia

The Bronze age initially included the Copper age. Copper smelting often happened before development of bronze, leading archaeologists to propose it as a separate age in the 1870s. Lead might have been smelted first since it's easy to do so. Copper might have been used in the Fertile Crescent (Timna Valley shows evidence of copper mining as early as 7000 BCE) due to the rarity of lead in the area. Lead and copper seem to have rapidly replaced stone tools as the quality of stone tools rapidly decreased.

Arsenic was added to copper to help make it stronger starting as early as 4200 BCE at Norşuntepe and Değirmentepe. The slag there doesn't contain arsenic, so it was added to the copper deliberately. Tennantite is an alloy of copper with iron, zinc, arsenic, and sulfur which may have led to arsenic being added to copper prior to the discovery and importation of tin.

Europe

First undisputed and direct evidence of copper smelting in Serbia dating about 5000 BCE with the discovery of an axe. Ötzi the Iceman, dated to about 3300 BCE, was found with a Mondsee copper axe.

South Asia

Copper bangles and arrowheads were found in Bhirrana, the first Indus civilization site, fashioned with local ore and dated between 7000 and 3300 BCE. This time period also saw the development of painted pottery.

North America

Smelting or alloying is disputed in North America as copper artifacts appear to be cold-worked rather than smelted, though there are copper artifacts dated as early as 6500 BCE, some of the oldest in the world.

China

Copper manufacturing gradually appeared in the Yangshao Period in China (about 5000-3000 BCE), with only Jiangzhai being the only site where they appeared in the earlier Banpo culture. The Yellow River valley appears to have been a major center of smelting.

Africa

In sub-Sahara Africa, scholars previously were unsure if there was a separate Copper Age, whether the region skipped the Copper and Bronze Ages and went directly to the Iron Age, or if copper and iron were smelted at the same time. Recent discoveries in the Agadez Region of Niger showed that copper metallurgy predated iron by about a thousand years. The two metals continued to be smelted and traded throughout the continent because copper was used as a medium of exchange and status symbol. Theories suggest that copper's redness, shine, and the sound it produced caused it to be valued by Africans for so long.

Housing and Cultural Development

Settlements often featured round houses with pointed roofs, potentially with walls around the houses. This time period was one of transition between the beginnings of the settled and stratified developments and the rise of empires that occurred in the Bronze and Iron Ages. There is evidence of trade in several regions due to the spread of copper and pottery, suggesting that people were mobile, or at least traded, between settlements. This is also the earliest we can trace linguistic movements, such as the spread of Proto Indo-European, which also suggest migration even with sedentary lifestyles becoming more dominant.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese art professor Wang Wei and renowned Canadian fantasy artist John Howe, one of the most well known artists of modern fantasy dragons, together with the oldest known depiction of a Chinese dragon from Yangshao culture, ca. 4700-2900 BC.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A small red pottery human head bottle

Yangshao culture, Banpo to Miaodigou phase, 4800-3500 B.C.

H. 20.7 cm.

#A small red pottery human head bottle#Yangshao culture Banpo to Miaodigou phase 4800-3500 B.C.#pottery#ancient pottery#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Lunar New Year Is the Year of the Dragon: Why the Beast Is a Big Deal in Chinese Culture

— By Chad De Guzman | Wednesday February 6, 2024 | Time Magazine

A traditional Chinese New Year dragon dance is performed in Liverpool’s Chinatown in January 2023.Getty Images

The last time China’s birth rates peaked was in 2012: that year, for every 1,000 people, there were 15 live births, a far cry from 2023’s 6.39. It was a statistical anomaly, considering the country’s ongoing state of demographic decline, which has proven extremely difficult to reverse. But 2024 may just see another baby boom for China, for the same reason as 12 years ago: it’s a Year of the Dragon.

Dragons are a big deal in Chinese culture. Whereas in the West dragons are often depicted as winged, fire-breathing monsters, the Chinese dragon, or the loong, is a symbol of strength and magnanimity. The mythical being is so revered that it snagged a spot as the only fictional creature in the Chinese Zodiac’s divine roster. And the imagery pervades society today—whether in boats, dances, or the stars.

International discourse about China’s economy or politics also often references the country as a “red dragon,” which critics have said subconsciously panders to Orientalism and fears of communism. But many Chinese proudly embrace the connection: China’s President Xi Jinping told former President Donald Trump in 2017 that the Chinese people are black-haired, yellow-skinned “descendants of the dragon.”

That’s why, in Years of the Dragon (which happen every 12 years), spikes in births tend to occur in China (as well as other countries with large Chinese populations, such as Singapore), as many aspiring parents try to time their pregnancies to result in a child born with the beast’s positive superstitious associations.

A Symbol of Prosperity

Where the Chinese dragon first came from is still debated by historians and archaeologists. But one of the most ancient images of the loong was unearthed in a tomb in 1987 in Puyang, Henan: a two-meter-long statue dating back to the Neolithic civilization of Yangshao Culture some 5,000–7,500 years ago. Meanwhile, Hongshan Culture’s Jade Dragon—a C-shaped carving with a snout, mane, and thin eyes—could be traced back to Inner Mongolia five millennia back.

Marco Meccarelli, an art historian at the University of Macerata in Italy, writes that there are four reliable theories for how the loong came to be: first, a deified snake whose anatomy is a collage of other worldly animals (based upon how, as ancient Chinese tribes merged, so did the animal totems that represent them); second, a callback to the Chinese alligator; third, a reference to thunder and a harbinger of rain; and lastly, as a by-product of nature worship.

Most of these theories point to the dragon’s supposed influence on water, because they are believed to be gods of the element, and thus, agricultural numen for a bountiful harvest. Some academics have said that across regions, ancient Chinese groups continued to enrich the dragon image with features of animals most familiar to them—for example, those living near the Liaohe River in northeast China integrated the hog into the dragon image, while people in central China added the cow, and up north where Shanxi is now, earlier residents mixed the dragon’s features with those of the snake.

A Symbol of Power

Nothing cemented the Chinese dragon’s might better than when it became a symbol of the empire. The mythical Yellow Emperor, a legendary sovereign, is said to have been fetched by a Chinese dragon to head to the afterlife. The loong are also said to have literally fathered emperors, or at least that’s what Liu Bang, the first emperor of the Han dynasty (202-195 B.C.), made his subjects believe: that he was born after his mother consorted with a Chinese dragon.

“The dragon totem and its corresponding clout were employed as a political tool for wielding power in imperial China,” Xiaohuan Zhao, associate professor of Chinese literary and theater Studies at the University of Sydney, tells TIME.

From then on, the loong was a recurrent theme across dynasties. The seat of the emperor was called the Dragon Throne, and every emperor was called “the true Dragon as the Son of Heaven.” D. C. Zhang, a researcher in the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, tells TIME that later dynasties even prohibited commoners from using any Chinese dragon motif on their clothes if they weren’t part of the imperial family.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) created the first iteration of a Chinese national flag featuring a dragon with a red pearl, which was to be hung on Navy ships. But as the Qing Dynasty weakened after several notable military losses, including the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and Boxer Rebellion of 1900, caricatures of the dragon began to be used as a form to protest against the government for its weakness, says Zhang. But with the dynasty’s fall after the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC)—which would then become Taiwan—in 1912, Zhang says the pursuit of a national emblem was temporarily cast aside.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), there had been renewed calls to find a unifying symbol to boost morale, and the dragon was among several animals considered. But when Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the quest for a unifying symbol for the Chinese was forgotten again, as the country pivoted priorities toward rapid industrial development.

A Symbol of Unity

Outside China, the dragon motif may have quickly caught on, but inside it, the dragon was not as influential until the 1980s, says Zhang. In 1978, Taiwanese musician Hou Dejian composed a song entitled “Heirs of the Dragon” as a means to express frustration over the U.S.’s decision to recognize the PRC as China’s legitimate government and sever diplomatic ties with the ROC (Taiwan). Lee Chien-fu, a Taiwanese student at the time, released a cover of the song in 1980 that grew immensely popular on the island.

Despite being a song decrying Taiwan’s disappointment, the song managed to cross the strait and also resonated with citizens of the mainland. Zhang says “China was becoming stronger” and its government tried to co-opt “Heirs of the Dragon” as it needed an emblem for unification and prosperity “which would be apolitical and would be inclusive to all Chinese nations even for those living abroad.” Hou, who had since moved to China, sang the song in a Chinese state variety show to usher in the Year of the Dragon in 1988.

But the song’s popularity also led it to be used against the Chinese leadership. Dissidents turned “Heirs of the Dragon” back into a protest anthem before the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, according to the South China Morning Post, with Hou even changing some of the lyrics according to Zhang. Hou was deported back to Taiwan in 1990, but his music stayed with the ethnically Chinese and the Chinese diaspora, Zhang says.

The song as well as China’s overt efforts to create a national symbol that transcends borders, Zhang says, play a large part in the lasting cultural significance of the loong. And the dragon’s historic regality has certainly helped boost the mythos, symbolism, and popular sentimental attachment for Chinese people today, says University of Sydney’s Zhao. “The basic characteristics, features, beliefs and practices associated with dragon totem and clout remain largely unchanged,” he says. “It’s very much a living tradition.”

#China 🇨🇳#Chinese Culture#Chinese Symbolism#Chinese Dragon 🐉 Symbolism#Lunar Year#Year of Dragon 🐉#Beast#Big Deal#Chad De Guzman#Time Magazine#Chinatown#Symbol of Prosperity | Power | Unity

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

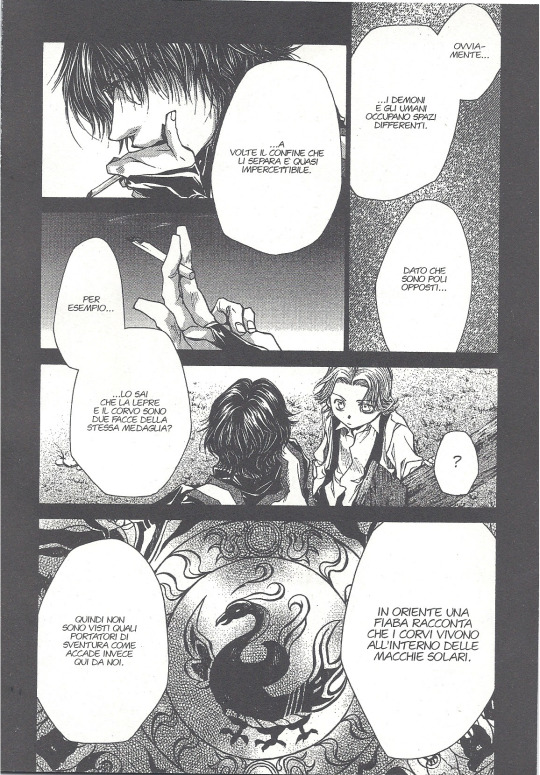

Sanzuwu/Yatagarasu (parte 1)

Mi piace questo sottile paragone tra gli umani/youkai e il corvo/coniglio e quindi Sole/Luna,Yang e Yin (ricordate che il Maten Kyo e il Seiten Kyo sono le Scritture che dominano lo Yin e Yang rispettivamente, tanto che lo stesso Maten Kyo aveva un lignaggio demoniaco prima dell’Anomalia) ma la cosa che ha attratto la mia curiosità è l’ultimo disegno raffigurante lo Yatagarasu o più precisamente il Sanzuwu (三足烏). Sappiamo come nella Minekura molti concetti, storie, miti ecc. spesso siano fusi e con-fusi come in questo caso e dunque vi è la necessità di scindere i vari pezzi pertanto dividerò in due parti (si spera XD) questa analisi.

Origini

Prima di parlare di esso però voglio agganciarmi al mito cinese implicito nell'ultima frase di Ukoku, come si può notare si vede un corvo (o cornacchia più probabilmente considerato l'areale di distribuzione del Corvus macrorhynchos colonorum nell'area del sito neolitico della cultura Yangshao e del Corvus macrorhynchos tibetosinensis se consideriamo la sovrapposizione geografica col C.m.colonorum della dinastia Shang), dalle parvenze più della fenice Fenghuang che di un corvide, inscritto nel disco solare poiché nel mito cinese e in quello giapponese derivato dal primo il corvo/la cornacchia è legato al Sole. In Cina le prime testimonianze del corvo solare (lo chiamo così perché come viene di solito chiamata “corvo/cornacchia a tre zampe” non mi convince molto e ve lo spiegherò più avanti) risalgono già nel 5000 a.C. dove viene rappresentato come uccello totemico e pare che il luogo d’origine di questa figura è Shandong provincia costiera situata lungo la regione più orientale della Cina.

Già nelle ceramiche neolitiche risalenti dal 5000 al 3000 a.C. troviamo la rappresentazione del corvo solare,detto anche Sanzuwu, nelle culture Yangshao e Longshan. Altre scoperte archeologiche nel villaggio Quanhu-chun (città di Liuzi-zhen, provincia di Shaanxi) rivelano la presenza di ceramiche su cui è rappresentato l’uccello totemico sulle cui ali spicca il Sole. Interessante notare come nella cultura Yangshao oltre al corvo solare gli è affiancato nella rappresentazione un rospo su una Luna crescente.

Notare il corvo a sinistra e il rospo sulla Luna a destra rappresentati in questo dipinto trovato nel sito archeologico di Mawangdui. L'immagine è lo stendardo del corteo funebre dipinto su seta della dinastia Han occidentale trovato nella tomba Mawangdui Han di Xin Zhui, nota anche come Signora Dai (morta nel 168 a.C.), raffigurante il rospo lunare (in alto a sinistra) e il corvo solare (in alto a destra). Qua vedete lo stendardo nella sua interezza, notare come ancora sia presente quell'antica traccia tripartita del mondo (cieli, mondo umano e mondo di sotto o aldilà di sciamanica memoria).

Questa rappresentazione già antica di 7000 anni,continuò per altri 3000 anni fino a che l’uccello divenne un corvo (o cornacchia) dorato e la rana in un rospo,ritratto di un credo secondo cui il corvo è l’anima del Sole mentre il rospo l’anima della Luna.

Sanzuwu, dal sito: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%87%91%E4%B9%8C/1513627?fromtitle=%E4%B8%89%E8%B6%B3%E9%B8%9F&fromid=5475459

È molto probabile che il motivo del corvo solare e il mito dei dieci corvi (che spiegherò anch'esso più avanti) si siano originati col popolo Shang il cui mito proliferò dal sud fino alla provincia Fujian,da notare tra l’altro che il loro mito della creazione asserisce che essi siano nati dall'uovo dell’uccello nero.

Nel libro di Sara Allen, Shape of the Turtle: myth, art and cosmos in early China, si dice:

“There appears to be an association between the ten-sun tradition and southern China. It might be argued that this was not a Shang tradition retained in the south during the Zhou, but one which originated in the state of Chu – a number of Shang sites in the Chu region and the connection between Shang and Chu culture has been confirmed by archaeological excavation. The most extensive finds were from Tianhu in Luoshan County, just south of the Huai River in southern Henan Province well connected to the south. The Zhou ruler claimed this title “wang” or king exclusively for the son of heaven tianzi history, in the Shang Dynasty, the rulers of many states used this title and were recognized by the Shang ruler who was also called king (wang).”

Col passare del tempo il mito dei dieci corvi solari si trasformò in quello dell’unico corvo solare e questo avvenne quando la dinastia Zhou conquistò e dominò sulla dinastia Shang nel 1045 a.C. da dieci corvi si passò ad uno solo tant'è che lo stesso Mencio cita Confucio dire “Il Cielo non ha due soli,i popoli non hanno due re…” comunque a livello popolare la credenza e il mito dei dieci soli rimase. A livello folkloristico si diceva che i dieci Soli fossero appollaiati sui rami del gelso (genere Morus) chiamato Fusang, situato ad Est ai piedi della Valle del Sole e che quindi questo albero fungesse da luogo d’origine dei dieci Soli.

Per capire come mai il corvo/cornacchia è una figura importante devo fare un’introduzione alla religione Shang impermeata di elementi sciamanici, ritualistici e religiosi vari, quindi scusatemi se vi rompo le balle con queste digressioni ma sono utili per meglio capire queste cose (cara Minekura quanto mi fai “dannare” per separare i vari pezzi che sapientemente hai fuso e con-fuso XD, non è vero lo adoro!).

Religione Shang

La religione del popolo Shang è molto vasta e complessa in quanto unisce elementi vari quali cerimonie, teologia, dogmi, rituali, divinazioni, elementi sciamanici ecc. La prima cosa da tenere in mente è l’importanza e il ruolo rilevante che il culto degli Antenati, con relativi sacrifici, aveva nel popolo Shang. La genealogia regale conteneva 35 Antenati storici, che includeva sia i regnanti pre-dinastici che dinastici con le relative consorti. Ad essi sono associati i miaohao ossia i “nomi-templi” a cui sono dati offerte e rituali vari. Oltre a questi troviamo figure storiche che hanno svolto il ruolo di importanti ministri quali Huang Yin, Yi Yin, Xian Wu e Xue Wu e insieme a loro ci sono figure mitologiche i cosiddetti gaozu ossia gli “Alti Antenati” e sono Nao, Er e Wang Hai.

Non è semplice poter schematizzare la religione Shang, tuttavia è possibile farsi un’idea tramite la seguente suddivisione:

Dio (o Dei) supremo: Di

Dei cosmici: Fang, Dongmu, Ximu

Forze naturali: Sole, Luna, Stelle, Fulmine, Pioggia

Spiriti naturali: Tu, Yue, He

Antenati mitici: Nao, Ji, Wang Hai, Wang Heng

Antenati pre-dinastici: Shang Jia,Bao Yi, Bao Bing, Bao Ding, Shi Ren, Shi Gui

Antenati dinastici: Da Yi, Da Ding, Da Jia, Bu Bing poi basta perché non ne ricordo più, sono un bel po'

Consorti degli Antenati dinastici: Bi Jia, Bi Yi ricordo solo queste due

Ministri reali: Huang Yin, Yi Yin, Xian Wu, Xue Wu, Jin Wu, Mie

Come detto i rituali svolgevano un ruolo dominante, ma anche come, quando farli e quali tipi (tutto questo era inciso sulle ossa da oracolo) ad esempio i sacrifici prevedevano molti tipi di cose e i più comuni erano: cibo, vino, buoi, maiali, pecore e cani (curioso poi che fosse praticata anche la castrazione di questi animali, soprattutto dei maiali). Oltre a questi si aggiungevano animali selvatici catturati durante le spedizioni venatorie e i sacrifici umani (guerrieri catturati e il metodo usato per il sacrificio era la decapitazione). Lo ammetto che sono della forte idea che lo Sciamanesimo abbia svolto un ruolo fondamentale in tutto questo in quanto era necessario il contatto tra i vari mondi (Inferiore, di Mezzo e Superiore) e per farlo erano necessari riti e offerte varie ma bisognava anche effettuarli nel modo corretto come la tradizione sciamanica esige, che poi sia divenuta una religione pre-burocratica non lo escludo anzi come tutte le cose c’è sempre evoluzione.

I sacrifici di vino e animali avevano proprio lo scopo di influenzare le forze cosmiche al fine di ottenere vantaggi, il che è più che naturale e logico. Le divinazioni avevano poi come scopo ultimo quelle di poter far diventare il regnante deceduto un Antenato per poi accedere al Dio supremo Di il quale controlla tutte le forze cosmiche e naturali, quindi si arrivava a negoziare ed eventualmente a controllare tali spiriti, Antenati e forze. Ai gaozu erano sacrificati ad esempio i buoi (gli animali grandi erano da preferirsi a quelli piccoli), specie se bianchi perché rari ma anche altri animali di colore bianco e in certi frammenti ossei su cui erano incise le divinazioni anche “uomini bianchi”,ma il carattere cinese bai per alcuni è da intendersi come “cento”.

Lo so che c’è molto, moltissimo da dire ma è per dare un’idea molto generale di quello che era la religione Shang, ora torniamo al nostro corvo.

Perché il corvo/cornacchia?

Il corvo (o cornacchia) è associato ai re Shang e alla dinastia Shang in generale e sappiamo come i regnanti divenissero gaozu una volta morti e come il regno dei vivi e dei morti sia altamente connesso,poiché il morto continua ad esistere come Antenato (tradizione sciamanica). Il mito Shang parla dei dieci Soli, il gruppo che governava aveva una relazione totemica con tali Soli e questo mito è intrinsecamente legato alla cultura Shang. Sappiamo anche che i corvi sono appollaiati sui rami del Fusang, albero di gelso i cui frutti sono rossi o bianchi e nelle iscrizioni oracolari ossee si dice che da esso ci siano molte bocche da cui si appollaiano i Soli, curioso poi notare come il carattere cinese che indica l’albero significhi anche “supporto” a significare come esso funga da supporto per i Soli (non è infrequente nelle mitologie la presenza di un albero che sorregga qualcosa che è vitale per il mondo). Un’altra cosa interessante, leggendo le parole di Ukoku in merito al fatto che i corvi risiedano all'interno delle macchie solari, è un passaggio del Shanhaijing un testo classico cinese che descrive vari luoghi e culture in modo mitologico. In esso si dice: “All'interno dei Soli ci sono giovani corvi; nella Luna rospi.” Anche nelle tombe della dinastia Han (ben postuma alla dinastia Shang) troviamo i Soli con i corvi inscritti e la Luna col rospo, notare poi che i corvi hanno due zampe e non tre, tuttavia in alcune tombe vedremo già tre zampe. Anche nella cultura giapponese né il Kojiki né il Nihon Shoki menzionano che lo Yatagarasu ha tre gambe, e il primo riferimento allo Yatagarasu con tre gambe è Wamyō Ruijushō (un dizionario giapponese di caratteri cinesi.), scritto a metà del periodo Heian (intorno al 930), e si pensa che a quel tempo volta Yatagarasu venne identificato con il corvo solare (a tre zampe), un uccello mitico della Cina e della Corea, e divenne a tre zampe. È possibile che la credenza nell'uccello come messaggero degli dei, originariamente esistente nella mitologia giapponese, si sia fusa con la credenza cinese nell'uccello spirituale del sole.

Per oggi mi fermo continuo la prossima volta con la seconda parte.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade de la Culture de Liangzhu

Les objets et les icônes en jade sont presque synonymes de la culture chinoise depuis des milliers d'années. Le jade (néphrite) fut travaillé pour la première fois en objets reconnaissables vers 6000 avant notre ère, pendant la période de la culture de Houli (c. 6500 - c. 5500 av. J.-C.). L'art du jade se développa à partir de cette époque pour atteindre son apogée à l'époque de la culture de Liangzhu (c. 3400-2250 av. J.-C.). Cette période vit également le développement de la stratification des classes établie au début de la culture de Yangshao (c. 5000-3000 av. J.-C.) et poursuivie par la culture de Hongshan (c. 4700-2900 av. J.-C.). Le jade, dont le travail prenait beaucoup de temps, était très prisé et seule la classe supérieure pouvait se l'offrir.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes