#american prison system

Text

""That's right, pal," says Number Seven. "And take it in these shops. If they'd even teach a guy a trade - make him learn a trade you wouldn't mind. Then a guy would have something to fall back on if he felt like hitting the straight and narrow. But what do they do? They put you to work making automobile plates, or something that's only done in prisons; stuff you couldn't get a job at outside if you wanted to; and the machinery is all twenty years out of date; and the instructors don't know anything about up-to-date methods; and the materials you get to work with are so lousy that you can't learn to do decent work even if you want to. Here I am. I've been working in the shoeshop for five years. What good will that do me? In the first place, the work I'm doing is done by women and children outside; it don't pay any- thing; and if I tried to get away with the lousy kind of work I've been taught to do, I wouldn't last two hours in an outside shop. The print shop is the only shop in here where a guy could learn a decent trade; but Christ, there's only room for forty guys in that shop, and you have to be a high-school graduate to get in there. That don't do the rest of us any good. There's a thousand men here, and only room for forty or so over in the print shop. And not only that, but So-and-So was always threatening to close the print shop because it didn't show enough profits. That's all they think about here. They damn about us learning a trade; all they is having the industries show a profit!"

"And take a guy when he gets out of here," says Number Ten. "Times are lousy outside. Even guys who know their trades, guys that can get swell references, can't get a job nowadays. And if they can't get work, how in the name of Christ are we going to get it even if we want it? And the jobs you can get don't pay anything - not enough to live on. A guy might better be in here than out there starving to death. How the hell is a guy going to live on twenty-five or thirty bucks a week, especially if he's married?"

- Victor F. Nelson, Prison Days and Nights. Second edition. With an introduction by Abraham Myerson, M.D. Garden City: Garden City Publishing Co., 1936. p. 213-214.

#words from the inside#prisoner autobiography#prison industries#released from prison#prison labor#failure of rehabilitation#american prison system#prison routine#prison days and nights#victor nelson#history of crime and punishment#convict labour#reading 2024

72 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

13TH | FULL FEATURE | Netflix

Combining archival footage with testimony from activists and scholars, director Ava DuVernay's examination of the U.S. prison system looks at how the country's history of racial inequality drives the high rate of incarceration in America. This piercing, Oscar-nominated film won Best Documentary at the Emmys, the BAFTAs and the NAACP Image Awards.

#youtube#13TH | FULL FEATURE#Prison#american prison system#white lies#white prison system#disinfranchisement

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

With a few exceptions, chain gangs were abandoned in the USA by 1955. Arizona's Maricopa county reintroduced the practice in 1995 and today the county runs the only all-female chain gang in the country.

Many women volunteer for the duty, looking to break the monotony of jail life.

Photos by Jim Lo Scalzo

August 2022

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

TSFF: Insight Prison Project

Prison education is essential if we want inmates to be able to be successful on the outside. And not commit any further crimes and not hurt any further any innocent people because now they know. There’s no successful future for them as criminals that they are hurting themselves and their families while in prison. As they and their families are much better off with them on the outside living…

youtube

View On WordPress

#America#American Corrections System#American Prison System#Prison Reform#Prison Rehabilitation#United States#Youtube

0 notes

Text

I think there's a major issue on how addictive drugs are taught to kids. It's always, "don't do drugs, and here's why they are bad." And while I guess it is a step, it doesn't go into why people indulge in harmful substances. Most people KNOW how bad they are, but they're desperate for any kind of release. Things like anxiety, depression, or just feeling hopeless in life leads people to drugs. And selling drugs is a quick way to make money. This also goes to how the prison system in the US is fucked up.

I don't want this to be too long so I won't go into major detail. But it just sets people up to fail. Things like homelessness itself is seen as illegal (sleeping in car, loitering, etc) because people are just uncomfortable with them. Not to mention how POC groups are more likely to be targeted. Hell, a police came up to me, my mom, and my sister one time and we all panicked because we thought we would die (he was super nice and only making sure we were okay because we had to stop on the side of the road, but some people aren't always that lucky.) Back on track. Once you're in prison, you're basically stuck as a criminal for your life. You can't get a job because having a criminal record is an automatic no. Getting a house is hard because landlords don't want former criminals. And the house you do get, you'll have trouble paying for because you can't find a good job. And so because of this, people will go back to a life of crime (like drug dealing as example) just to make a buck. Which can ultimately lead to them getting arrested again.

#america#prison system#american prison system#america issues#poc#poc issues#social issues#prison#drugs#drug dealing#police#police system

1 note

·

View note

Text

Staff and inmates began playing basketball together.

"Humankind: A Hopeful History" - Rutger Bregman

0 notes

Note

May I present the best headline I've seen today:

Look, the Fulton County people have already said they plan to give him the full works: fingerprinting, mugshot, perp walk, releasing height/weight, etc, all the usual criminal treatment that he's managed to avoid so far. So yeah, he's gonna fucking HATE it, and if I don't see the mugshot everywhere on everything and made into all the memes you can think of, the internet will have failed me.

#textsfromgravityfallsblog#ask#politics for ts#the giant orange monster#i don't approve of the carceral system etc etc but also if there is anyone who deserves the worst the american prison system has to offer#it's the fucking orange fuhrer#so yeah

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

god american vandal is so good. when peter and sam have to look into each other as suspects and peter actually presents a compelling case about sam's potential crush on gabi but then it like. changes genre as sam gets frustrated with peter for making him look bad and you get this like shocking look at the real consequences of peter's investigation. the moments of like. oh these are real people and his meddling affects the real people in his life and his friendships are falling apart in his search for the truth. fuck I love you american vandal.

#what if this silly mockumentary about graffiti dicks actually made a meaningful commentary#about journalism and the prison industrial system and american school systems#american vandal

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

At age 17, Donnell Drinks was one of many young men in Philadelphia who went to prison for life without parole. Today, the city has resentenced more of those prisoners than any other jurisdiction.

Published Aug. 15, 2023Updated Aug. 18, 2023

Donnell Drinks woke up one morning to banging on his door in the projects of North Philadelphia. It was the late 1980s, and Mr. Drinks, who was 15 and the oldest of three boys, had nodded off after taking his youngest brother to school. He should have been at school himself, but he had stopped going earlier that year. It wasn’t a truant officer at his door, though — no one had ever come knocking about that. Instead, sheriff’s deputies were waiting outside. They were there to evict his family.

The officers told him to get out, not bothering to ask if there was an adult around, which there wasn’t. Mr. Drinks’s dad had abandoned the family a decade earlier, and his mom was in the throes of crack cocaine addiction. For years, Mr. Drinks had been raising his younger brothers, and he had just become a father himself. He’d dropped out of school to support his family by selling drugs, a transition that felt so natural he hardly remembered how it happened.

Groggy and panicked, Mr. Drinks scanned the apartment for essentials, stuffed a shopping cart with clothes for his brothers and wheeled the cart up the road to his grandmother’s overcrowded rowhouse. The officers never asked where he was going.

“There was not one adult that said, Hold a minute. We need to call somebody,” Mr. Drinks said. “Not one adult said, That’s a child.”

At the time, Black teenage boys like Mr. Drinks were being treated less as children in need of help and more as if they were threats to society itself. Crime was rising nationwide, particularly in Philadelphia, where, in 1990, the city recorded 500 murders in a year for the first time. It was a terrifying period, especially for people living in poorer neighborhoods where the violence was worst. But the rhetoric, perpetuated by public officials and overheated headlines, suggested that a new morally depraved generation of teenagers — particularly Black teenagers — were to blame. This idea gave rise to the “superpredator” era and a raft of laws cracking down on juveniles that followed.

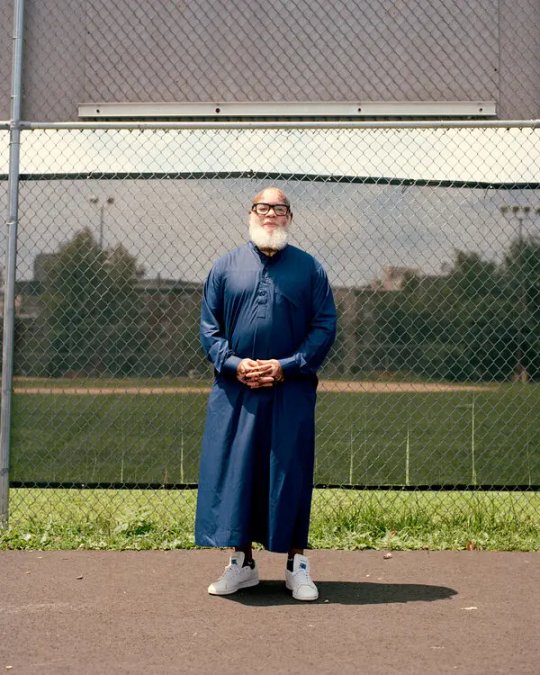

Mr. Drinks, now 50 years old, is a small man with a stocky frame and a warm, gaptoothed smile. He keeps his salt-and-pepper beard meticulously fluffed. An animated storyteller who is quick with a metaphor and a motivational quote, he becomes guarded when describing his upbringing — not just because it’s painful, but because he doesn’t want anyone to think he’s trying to justify what happened next. “This is context,” he said, “not excuses.”

In February 1991, when he was 17, Mr. Drinks and his 22-year-old girlfriend, who was a police officer, tried to rob a man named Darryl Huntley. They staked out Mr. Huntley’s house and forced him and his fiancée inside at gunpoint. That violent act led to others. Mr. Drinks stabbed Mr. Huntley, fatally, and was shot himself. Mr. Drinks was arrested while he was in the hospital recovering from his injuries.

By the time Mr. Drinks was brought to trial for Mr. Huntley’s murder, Philadelphia had a new district attorney: Lynne Abraham, a former judge who went on to hold the office for nearly two decades. Pennsylvania law already made life sentences mandatory for first- and second-degree murder convictions, but Ms. Abraham responded to the era’s surge in violent crime by aggressively pursuing the death penalty, an approach that once earned her the moniker the “deadliest D.A.”

She also called for tougher punishments for juveniles. In 1994, she pushed for legislative changes to give prosecutors more power to charge juveniles as adults. “You don’t get any bonus for being under a certain age,” she told The Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. The next year, the state passed a law that required prosecutors to treat children 15 and older as adults when they were charged with certain crimes.

Though Philadelphia had already sentenced many young people to life without parole, under Ms. Abraham’s watch — and with the city’s murder rate remaining high throughout the ‘90s — the number getting that sentence in Philadelphia rose quickly. For some, it may have been a deal worth taking to avoid the death penalty.

Mr. Drinks was tried as an adult and initially sentenced to death. In 1993, his sentence was reduced to life without parole. (His then-girlfriend, who received the same sentence, remains in prison.)

He most likely would have died in prison, but while Mr. Drinks was behind bars, a national effort began to rethink the culpability of young people in the eyes of the law. In the 2005 case Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for minors, leaning heavily on new scientific research that showed — “as any parent knows,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote — that young people are not like adults. They are more impulsive, reckless and susceptible to persuasion.

The court did not question that minors should pay for committing heinous crimes, but in banning the most severe punishment, it affirmed the possibility “that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.” Real change, Justice Kennedy suggested, was possible.

Mr. Drinks had been in prison for more than a decade when the Roper decision came out. Then one day, a Philadelphia lawyer named Bradley Bridge traveled to the upstate Pennsylvania prison where Mr. Drinks was locked up, and explained to him and the other men who had been given life sentences as boys what the ruling could mean for them.

Striking down the death penalty for minors was only the beginning, Mr. Bridge said. Soon, he predicted, the court would apply the same logic to outlaw mandatory life sentences for juveniles too, potentially giving Mr. Drinks and others serving such sentences a shot at freedom — and giving the city of Philadelphia a chance to rewrite its legacy.

A long list of friends

Mr. Bridge had been delivering his speech inside prisons throughout Pennsylvania for months before Mr. Drinks heard him speak. Mr. Bridge worked for the Defender Association of Philadelphia and had spent nearly three decades representing prisoners who were appealing their sentences. When the Roper ruling came down, he was involved in the case of a teenager facing a mandatory sentence of life without parole. He understood immediately the opportunity that the Supreme Court’s ruling presented not just for his client, but for scores of prisoners.

For Mr. Bridge, it meant pursuing a novel legal theory that might help dismantle what he viewed as a particularly unjust part of the justice system. “Children are children, and they make mistakes,” Mr. Bridge said. “But they grow and change.”

Mr. Bridge began the enormous undertaking of compiling a list of all the prisoners in Pennsylvania who were sentenced to life as minors. No one in the state had ever kept track of this group, who came to be called “juvenile lifers” in the courts and “child lifers” by some of the inmates themselves.

He expected the list to be long. He didn’t expect it to eventually include more than 500 names, nearly one-fifth of the more than 2,800 child lifers in the country. More than 300 of them had come through Philadelphia’s system, making a city with less than 1 percent of the country’s population responsible for more than 10 percent of all children sentenced to life in prison without parole in the United States. No other city compared. Even more glaring: More than 80 percent of Philadelphia’s child lifers were Black. Nationally, that figure was roughly 60 percent.

Racism “undoubtedly occurred in every phase of the criminal justice system,” Mr. Bridge said. “This created an opportunity to try to fix things that had been broken.”

After the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for minors, Bradley Bridge started encouraging inmates sentenced to life as children to prepare for the possibility that the court would eventually revisit the constitutionality of their sentences, too.

His partner in this work was Marsha Levick, who had co-founded the Juvenile Law Center in 1975 as an idealistic young graduate of Temple University’s law school and gone on to become one of the nation’s foremost experts on juvenile sentencing.

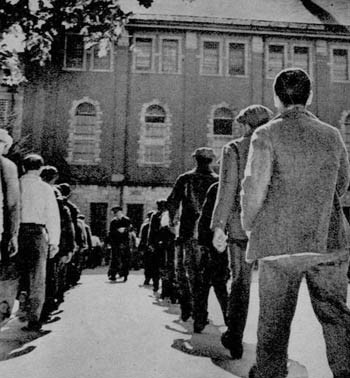

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick began traveling the state, arranging meetings with the people on Mr. Bridge’s list and adding names as they went. Mr. Bridge’s first stop was Graterford, a maximum-security facility outside of Philadelphia that, at the time, held more child lifers than any prison in the state. Dozens of men crowded into Graterford’s chapel to hear what Mr. Bridge had to say.

“People wanted to know what was coming down the pike,” remembered Kempis “Ghani” Songster, who was in the room that day. “Is this a ray of light flickering on?”

At age 15, Mr. Songster stabbed another teenager to death in a crack house. Both were runaways working for the same gang. He was given a life sentence for his crime, but it wasn’t until that meeting in 2006, nearly two decades after he went to prison as a scrawny kid who couldn’t grow a beard, that he realized how many other lifers at Graterford had also arrived as teenagers.

“It was like, Whoa, he’s been here since he was a kid, too?” Mr. Songster said. “A lot of us who were child lifers didn’t really know that we were in a distinct class.”

There had never been a reason to talk about age. The courts had treated them as adults, and if anything, being marked as a child in a violent adult prison would only have made them more vulnerable. Now, there was power in the identity.

The child lifers inside Graterford began organizing. They quickly formed a committee called Juvenile Lifers for Justice, which met weekly to discuss the evolving law and science around adolescent development. They drafted pamphlets, circulated newsletters to other prisons and their family members, and kept one another motivated around their common cause.

These conversations also started to change how some of the men thought about why they had committed such serious crimes.

Mr. Songster said he never felt “entitled” to be free. “I can’t wash the blood off my hands that’s on my hands,” he said. But the emerging research, which showed brains aren’t fully developed until people get into their 20s, gave him new understanding. “It made me curious about myself,” Mr. Songster said of the research. “I knew I was a good person, but I couldn’t reconcile the person that I became and I know I am with the person that committed that horrible act.”

The child lifers were also reaching out beyond the prison walls. They invited politicians to visit Graterford and partnered with nonprofit organizations to distribute supplies to local schools.

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was also sentenced as a minor and was the president of Graterford’s N.A.A.C.P. chapter during this period.

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick became frequent fixtures at the prison. At each of these visits, Ms. Levick was struck by how the men — imprisoned at such a young age and last in line for any prison edification programs because of their status as lifers — had mastered the nuances of the law and were orchestrating a statewide grass-roots movement from inside prison. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was locked up at Graterford and has since been released.

Mr. Drinks had spent 10 years at Graterford, but after he was transferred upstate, newsletters coming out of Graterford and messages passed along from old friends became his lifeline. Without a lawyer of his own, he kept his case alive by adapting draft legal petitions circulated by Mr. Bridge. And he documented his accomplishments in prison — articles he’d written, certificates he’d earned, thank-you notes from the nonprofits he’d raised money for — until he had three manila envelopes’ worth of records illustrating all the ways he’d grown.

Still, he never quite let himself believe that Mr. Bridge’s prediction would pan out. He wanted to be prepared, but he was also prepared to be let down.

“It’s like throwing water out of a boat that’s sinking,” Mr. Drinks said. “You’ve got to do it anyway, because if you don’t, the water’s going to get you.”

Throughout this period, lawyers around the country, including Ms. Levick and Mr. Bridge, were bringing new cases, trying to apply the rationale in the Roper ruling to other kinds of sentences for juveniles. At the national level, a key leader in this work was Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit.

Mr. Stevenson saw a connection between the superpredator era and the overwhelming number of young Black boys who had been locked away for life.

“You had these criminologists going around saying that some children aren’t children. Some kids look like kids, but they’re really, quote, superpredators,” he said. “That narrative was so prevalent, so persuasive, that you see states all over the country lowering the minimum age for trying children as adults.”

In 2008, the Equal Justice Initiative found 73 children who had been given sentences of life without parole when they were 13 and 14 years old. And all of the people who received those sentences for crimes other than homicide were children of color.

“It just said something about the way in which race was a proxy for a presumption of dangerousness, this presumption of irredeemability,” Mr. Stevenson said.

Then came a series of breakthroughs. In 2010, the Supreme Court abolished sentences of life without parole for minors charged with crimes other than murder. Two years after that, Mr. Stevenson appeared before the court on behalf of two young men who were sentenced to life without parole when they were 14. In its decision in Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court struck down all mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles. Four years later, in a case called Montgomery v. Louisiana, for which Ms. Levick served as co-counsel, the court made that decision retroactive, fulfilling the prediction Mr. Bridge made in the Graterford chapel a decade before, and giving more than 2,800 child lifers across the country the right to have their sentences revisited.

Mr. Drinks remembers the first time he got a look at Mr. Bridge’s list. It was filled with the names of people he’d known for years, but had never known were child lifers. There was Abd’Allah Lateef, the soft-spoken guy he’d always admired at Graterford, even when he griped about Mr. Drinks’s loud music. There was Luis “Suave” Gonzalez, a big talker whom Mr. Drinks had encouraged to lead one of Graterford’s Latin American cultural exchange groups. And there was Don Jones, a friend so close, Mr. Drinks said, “my brothers call him brother.”

“That was my tear-shed moment,” Mr. Drinks said. “I knew I was on the list, but going down the list and seeing genuine friends?” Now, they might all have a shot at freedom — a shot, but not a guarantee.

A block in North Philadelphia. Donnell Drinks sold drugs in the area as a teenager and was convicted of homicide at age 17 in a robbery gone wrong.

‘The election changed everything’

The Supreme Court’s rulings in Millerand Montgomery marked an important rethinking of culpability when it comes to children who commit the most serious crimes. But the practical implications of the rulings were limited: the court hadn’t abolished all life without parole sentences for children — only ones where state laws made the sentences mandatory.And while child lifers now had a chance to make a case for their release, prosecutors could still seek new life sentences. In other states with high numbers of child lifers, including Michigan and Louisiana, as well as some parts of Pennsylvania, that’s just what they did.

In Philadelphia, however, all of the list-gathering and planning that had been taking place for more than a decade began to pay off. Most of the state’s child lifers had been prosecuted in the city, and it was up to its district attorney’s office and court system to move hundreds of people through the resentencing process. “Philadelphia was bad, and everybody recognized it was bad,” Mr. Bridge said.

Ms. Levick added, “In a way, the whole world was watching.”

Philadelphia soon began resentencing and releasing child lifers, starting with those who’d been in prison the longest. But while R. Seth Williams, Philadelphia’s district attorney, initially committed not to resentence anyone to life without parole, he stuck to strict new state sentencing guidelines, which meant that Mr. Drinks and others who had been swept up in the ’90s, would most likely spend many more years in prison.

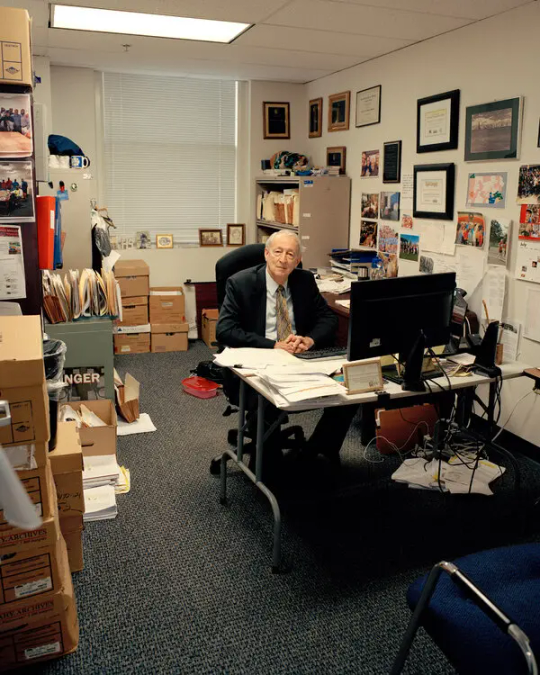

Marsha Levick, an expert on juvenile sentencing, visited inmates. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

Mr. Williams viewed this approach as the only way to honor the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Pennsylvania government’s consensus and the rights of the victims. “People often only look at the factors for the defendant. I understand. But they often forget there was a victim,” Mr. Williams said. “Someone was murdered. We just can’t just sweep that under the rug.”

Then came a twist that no one predicted. In March 2017, a little over a year after the Montgomery decision, Mr. Williams was indicted on charges including bribery and extortion and later sentenced to five years in prison. Almost as surprising was who was elected to be his successor: a sharp-elbowed former public defender and criminal defense attorney named Larry Krasner.

Whatever Ms. Abraham, the former district attorney, had been to the city in the 1990s, Mr. Krasner swore to be the opposite. (Ms. Abraham did not respond to requests for comment.) He had run against the death penalty and mass incarceration, and vowed to decriminalize marijuana and end cash bail. One of his first moves after taking office in January 2018 was to fire 31 prosecutors in a purge that became known as the Snow Day Massacre.

When it came to juvenile lifers, Mr. Krasner was more open than his predecessor to considering how people had changed in the decades since committing their crimes. Chesley Lightsey is a former assistant district attorney who worked on Mr. Drinks’s case and others under both administrations. “It took time for me to wrap my head around it: ‘Okay, now we can have much more of a conversation about this,’” she said about the change when Krasner was elected. “It was just a different perspective.”

Under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors paid special attention to reports drafted by mitigation specialists. Those specialists, who are essentially professional storytellers for defendants, interviewed juvenile lifers, their families and anyone else who could offer context. They asked questions about how the inmates had been raised, the trauma and pain that had influenced their actions, what they had done with their time in prison and what they planned to do upon release.

By the time Mr. Krasner took office in January 2018, Mr. Drinks had spent hours spilling his soul to a lawyer and mitigator named Rachel Miller. Over the course of countless calls and several in-person visits, Ms. Miller wove the story of Mr. Drinks’s life into a memo, complete with a two-inch stack of documents highlighting his accomplishments.

The memo covers the most painful moments of Mr. Drinks’s childhood: being abandoned by his father, his mother’s struggle with addiction, getting evicted. It describes how Mr. Drinks would skip school to collect the family’s food stamps before his mother could pawn them for drugs and how, when his mother turned violent, he would take the brunt of her beatings in an attempt to spare his brothers.

But the memo also tells the story of a grown man who spent his time behind bars trying to atone for the crime that put him there. Among the stack of documents is a community college transcript filled with A’s and B’s, an agenda for a workshop he organized with victims’ rights advocates and a photo of him beaming behind a giant check made out to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Perhaps most meaningful to Mr. Drinks were the letters he received from other incarcerated men who were members of a youth group he founded attesting to all the ways the group, and Mr. Drinks, had saved them. “I did not know the child that committed the crime he is in here for,” read one of the letters, “but the man I do know is not that same person.”

Before Mr. Krasner’s election, Mr. Drinks was offered a deal of 35 years to life, which would have made him eligible for parole in 2026. Shortly after Mr. Krasner took over in 2018, Mr. Drinks got a new offer: time served.

“The election changed everything,” Mr. Drinks said, referring to Mr. Krasner’s victory.

“I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to,” Mr. Drinks said of the murder he committed. “I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Mr. Drinks’s case was not unique. Researchers at Montclair State University have found that, under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors began offering child lifers new sentences that were, on average, 11 years shorter than the ones offered to those same people under Mr. Williams. Crucially, the researchers found that child lifers’ release had a negligible effect on public safety. Seven years after they started coming home, the rearrest rate for Philadelphia’s child lifers hovers around 5 percent. That’s small compared with the national rate, where 40 percent of people with past murder convictions are rearrested within the first five years, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. As of early this year, only three of the city’s child lifers who were rearrested have been convicted (for marijuana possession, contempt and robbery in the third degree), according to the Montclair State researchers.

For Mr. Krasner, these numbers reveal as a lie the idea that some people are so incapable of change that they should never be offered a shot at it. “It was always wrong to believe that people are either saints or they’re sinners,” Mr. Krasner said.

At his resentencing hearing in April 2018, Mr. Drinks read aloud from a letter before a gallery filled with friends and family, as well as the loved ones of Mr. Huntley, his victim. He apologized to Mr. Huntley’s family and said he knew he had no right to ask anyone in the room for forgiveness, and so he didn’t. But he did promise to spend the rest of his life making amends.

Mr. Huntley’s family members also made statements to the court. In a handwritten letter, Mr. Huntley’s sister described her brother as a loving and giving person. She explained how his murder had crushed her family, derailed her own education and deprived her children of ever knowing their uncle. “My mother still is deeply hurt and our family find it difficult to celebrate Valentine’s Day,” she wrote, “because these horrible, horrible actions took place that evening leading into his death.” She told the court that she did not want to see Mr. Drinks released.

Mr. Huntley’s sister did not respond to an interview request, but Suzanne Estrella, who runs the Office of Victim Advocate in Pennsylvania, said that many victims’ families “flat-out just do not” agree with the resentencings. But she said there were also many families that understood and accepted them. “You have survivors who have lost loved ones and survivors who have loved ones who are incarcerated,” Ms. Estrella said. “So you see all those perspectives coming to the table at the same time.”

As painful as it was, Mr. Drinks said he appreciated Mr. Huntley’s family’s honesty. “I felt it, and I understood it,” he said. “I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to. I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Three months after the hearing, having won the approval of the parole board, Mr. Drinks met his brothers as he walked out of prison for the first time in nearly three decades. Mr. Drinks remembers his sense of disbelief and being a little carsick as they drove the four hours back to Philadelphia, where he would move in with his brother Damon. The whole way home, he couldn’t shake the feeling that someone was following close behind. “I didn’t want to look back,” he said, “so I kept looking ahead.”

Donnell Drinks married Shekia Drinks two years ago. But he hasn’t been able to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife.

A return to the 1990s?

Of the more than 300 child lifers who became eligible for resentencing in Philadelphia in 2016, all but about a dozen have been resentenced, and more than 220 have been released, the majority of them on lifetime parole. That’s nearly a quarter of the roughly 1,000 total child lifers who have been released across the country. These numbers make Philadelphia, once an outlier in imprisoning minors for life, now an outlier in letting them go. By 2020, the city had resentenced more child lifers than Michigan and Louisiana combined.

What set the city apart, said Mr. Stevenson, of the Equal Justice Initiative, was not just the buy-in from local officials and public defenders, but also the community of child lifers who became their own best argument for release.

“It was the way they organized, the way they cared for one another, the way they modeled a kind of readiness to contribute to society,” Mr. Stevenson said. “These young people had been told they were going to die in prison. Some of them just never accepted that.”

Since the Supreme Court decisions, more than half of all states have outlawed life without parole sentences for children altogether, reducing the number of child lifers left in the country to fewer than 600, according to the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national nonprofit. Mr. Stevenson’s organization is now working to raise the minimum age at which children can be tried as adults in 11 states, including Pennsylvania, where there is no age floor. Other states are considering abolishing mandatory life without parole sentences for people under 21.

While life without the possibility of parole sentences for juveniles are now rare, they are not unheard of. The now solidly conservative Supreme Court has issued a ruling that could lower the bar for judges to apply the sentence to children in states where it is still allowed. A prosecutor in Oakland County, Mich., is seeking life without parole for a mass shooter who was 15 when he killed four students at his high school in 2021. A judge will have to weigh the horror of his crime against the possibility that, over time, he could change.

The United States is still the only country in the world that gives courts the discretion to send children to prison without the chance of proving themselves later in life at a parole hearing. And the tough-on-crime rhetoric of the 1990s is making a comeback, thanks to a spike in violent crime that began at the outset of the pandemic. In Philadelphia alone, the murder rate has surpassed the record set in 1990 two years in a row, with young people emerging as both victims and perpetrators.

Mr. Drinks and Mr. Jones started an anti-violence group in Philadelphia and sometimes walk the streets handing out pamphlets.

Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming.

Though this uptick in crime is showing signs of decline, it has prompted a nationwide backlash against progressive prosecutors, including Mr. Krasner, whose comparatively lenient approach has become a lightning rod in local politics. Mr. Krasner was recently the subject of an impeachment effort by Pennsylvania Republicans, and even some Democrats raced to condemn his record during the city’s mayoral primary in May.

Those who were released have become some of the loudest voices for building upon the fragile gains they fought for while on the inside. Their fight now is about abolishing life without parole for everyone, getting young people out of adult prisons and addressing the underlying causes of the violence plaguing Philadelphia and other major cities.

“If you would have dealt with a lot of my issues,” Mr. Drinks said, “they probably would not have escalated to crime.”

It’s not that Mr. Drinks and his fellow activists believe juveniles convicted of murder should not be held accountable. “When we talk to legislators, we don’t say: Throw the doors open, and everybody’s coming home,” Mr. Drinks said. “Our conversation is always that everybody deserves an opportunity to show they’re worthy of coming home.”

Today, Mr. Drinks coordinates a network of former child lifers through the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. In any given week, he might be found with two cellphones in hand, flying to Alabama to urge progressive prosecutors to stay the course, organizing retreats for formerly incarcerated men and women, or canvassing city streets through an anti-violence nonprofit he co-founded with Mr. Jones, his friend from Graterford.

Mr. Drinks and other child lifers know that they embody for the public what all the research said about a young person’s capacity for change, and they are keenly aware that their example could help secure other people’s freedom. But they are also wary of being used to suggest that the system works, or allowing it to conceal just how difficult their re-entry into the outside world has been.

While several of Philadelphia’s child lifers have gone on to become an Ivy League lecturer or nonprofit executive, many more are working minimum-wage jobs or are unable to find work. Some are in bad health. Four have died. Nearly all of them are on lifetime parole, with the possibility of being sent back to prison forever looming.

Mr. Drinks credits his brothers, Damon and Kareem, for making his homecoming easier. Throughout Mr. Drinks’s incarceration, the three brothers had remained as close as the prison system would allow, keeping up visits even when he was transferred far away. Often, Damon Drinks would bring along Mr. Drinks’s son, who was just 3 when his father was arrested, and is now a grown man with a family of his own. It is thanks to his brothers, Mr. Drinks says, that he was able to maintain a relationship with his son at all.

Mr. Drinks, in Fairmount Park, said his brothers visited him while he was in prison and have helped him readjust to life on the outside.

Damon and Kareem Drinks’s support continued once their big brother was released. They took him shopping, kept him housed and partnered with him to start a local printing company not far from the city courthouse. Mr. Drinks has not had to struggle to survive, but that doesn’t mean he has not struggled. Five years after he left prison, the terms of his parole still prohibit him from leaving the county of Philadelphia without permission. He got married two years ago, but he has yet to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife. And he lives with the constant fear that one act of violence by any of the state’s other child lifers could spell the end of his own tenuous freedom.

This fear is part of what keeps Mr. Drinks connected to the men who were once boys with him on the inside. Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming. These bonds are as much a product of their shared experiences as they are a defense against their shared vulnerabilities.

“We’re each other’s co-defendants,” Mr. Drinks said. “We see people want to stray, it’s like, No, come on. We’re going to get to this finish line together.”

Mr. Drinks hugs Michael “Smokey” Wilson, another former child lifer.

#How People Sentenced to Life in Prison Made Their Case for Release#prison#american injustice system.#penal injustice#sentencing disparities#adultification#Black Lives Matter

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don't care about THE US!!!!!!!! *my telekinesis throws everything across the Room*

#if i have to see another psa adressed to 'all students' or 'everyone between the ages of 18-25' that actually just applies to us americans#i'm going to commit homicide#also every post that is like 'The education/public transport/prison system is good/bad/functional/whatever' like oh yeah?? which one

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Progressives’ design for the penitentiary did alter the system of incarceration. Their ideas on normalization, classification, education, labor, and discipline had an important effect upon prison administration. But in this field, perhaps above all others, innovation must not be confused with reform. Once again, rhetoric and reality diverged substantially. Progressive programs were adopted more readily in some states than in others, more often in industrialized and urban areas, less often in southern, border, and mountain regions. Nowhere, however, were they adopted consistently. One finds a part of the program in one prison, another part in a second or in a third. Change was piecemeal, not consistent, and procedures were almost nowhere implemented to the degree that reformers wished. One should think not of a Progressive prison, but of prisons with more or less Progressive features.

The change that would have first struck a visitor to a twentieth-century institution who was familiar with traditional practices, was the new style of prisoners’ dress. The day of the stripes passed, outlandish designs gave way to more ordinary dress. It was a small shift, but officials enthusiastically linked it to a new orientation for incarceration. In 1896 the warden of Illinois’s Joliet prison commented that inmates “should be treated in a manner that would tend to cultivate in them, spirit of self-respect, manhood and self-denial. . . , We are certainly making rapid headway, as is shown by the recently adopted Parole Law and the abolishment of prison stripes.” In 1906, the directors of the New Hampshire prison, eager to follow the dictates of the “science of criminology” and “the laws of modern prisons,” complained that “the old unsightly black and red convict suit is still used. . . . This prison garb is degrading to the prisoner and in modern prisons is no longer worn.” The uniform should be grey: “Modern prisons have almost without exception adopted this color.” The next year they proudly announced that the legislature had approved an appropriation of $700 to cover the costs of the turnover. By the mid-1930’s the Attorney General’s survey of prison conditions reported that only four states (all southern) still used striped uniforms. The rest had abandoned “the ridiculous costumes of earlier days.”

To the same ends, most penitentiaries abolished the lock step and the rules of silence. Sing-Sing, which had invented that curious shuffle, substituted a simple march. Pennsylvania’s Eastern State Penitentiary, world famous for creating and enforcing the silent system, now allowed prisoners to talk in dining rooms, in shops, and in the yard. Odd variations on these practices also ended. “It had been the custom for years,” noted the New Hampshire prison directors, “not to allow prisoners to look in any direction except downward,” so that “when a man is released from prison he will carry with him as a result of this rule a furtive and hang-dog expression.” In keeping with the new ethos, they abolished the regulation.

Concomitantly, prisons allowed inmates “freedom of the yard,” to mingle, converse, and exercise for an hour or two daily. Some institutions built baseball fields and basketbaIl courts and organized prison teams. “An important phase in the care of the prisoner,” declared the warden of California’s Folsom prison, “is the provisions made for proper recreation. Without something to look forward to, the men would become disheartened. . . . Baseball is the chief means of recreation and it is extremely popular.” The new premium on exercise and recreation was the penitentiary’s counterpart to the Progressive playground movement and settlement house athletic clubs.

This same orientation led prisons to introduce movies. Sing Sing showed films two nights a week, others settled for once a week, and the warden or the chaplain usually made the choice. Folsom’s warden, for example, like to keep them light: “Good wholesome comedy with its laugh provoking qualities seems to be the most beneficial.” Radio soon appeared as well. The prisons generally established a central system, providing inmates with earphones in their cells to listen to the programs that the administration selected. The Virginia State Penitentiary allowed inmates to use their own sets, with the result that, as a visitor remarked “the institution looks like a large cob-web with hundreds of antennas, leads and groundwires strung about the roofs and around the cell block.”

Given a commitment to sociability, prisons liberalized rules of correspondence and visits. Sing-Sing placed no restrictions on the number of letters, San Quentin allowed one a day, the New Jersey penitentiary at Trenton permitted six a month. Visitors could now come to most prisons twice a month and some institutions, like Sing-Sing, allowed visits five times a month. Newspapers and magazines also enjoyed freer circulation. As New Hampshire’s warden observed in 1916: “The new privileges include newspapers, that the men may keep up with the events of the day, more frequent writing of letters and receiving of letters from friends, more frequent visits from relatives . . . all of which tend to contentment and the reestablishment of self-respect.’? All of this would make the prisoners’ “life as nearly normal as circumstances will permit, so that when they are finally given their liberty they will not have so great a gap to bridge between the life they have led here . . . and the life that we hope they are to lead.”

These innovations may well have eased the burden of incarceration. Under conditions of total deprivation of liberty, amenities are not to be taken lightly. But whether they could normalize the prison environment and breed self-respect among inmates is quite another matter. For all these changes, the prison community remained abnormal. Inmates simply did not look like civilians; no one would mistake a group of convicts for a gathering of ordinary citizens. The baggy grey pants and the formless grey jacket, each item marked prominently with a stenciled identification number, became the typical prison garb. And the fact that many prisons allowed the purchase of bits of clothing, such as a sweater or more commonly a cap, hardly gave inmates a better appearance. The new dress substituted one kind of uniform for another. Stripes gave way to numbers.

So too, prisoners undoubtedly welcomed the right to march or walk as opposed to shuffle, and the right to talk to each other without fear of penalty. But freedom of the yard was limited to an hour or two a day and it was usually spent in “aimless milling about.” Recreational facilities were generally primitive, and organized athletic programs included only a handful of men. More disturbing, prisoners still spent the bulk of non-working time in their cells. Even liberal prisons locked their men in by 5:30 in the afternoon and kept them shut up until the next morning. Administrators continued to censor mail, reading materials, movies, and radio programs; their favorite prohibitions involved all matter dealing with sex or communism. Inmates preferred eating together to eating alone in a cell. But wardens, concerned about the possibility of riots with so many inmates congregated together, often added a catwalk above the mess hall and put armed guards on patrol.

Prisoners may well have welcomed liberalized visiting regulations, but the encounters took place under trying conditions. Some prisons permitted an initial embrace, more prohibited all physical contact. The rooms were dingy and gloomy. Most institutions had the prisoner and his visitor talk across a table, generally separated by a glass or wire mesh. The more security-minded went to greater pains. At Trenton, for example, bullet-proof glass divided inmate from visitor; they talked through a perforated metal opening in the glass. Almost everywhere guards sat at the ends of the tables and conversations had to be carried on in a normal voice; anyone caught whispering would be returned to his cell. The whole experience was undoubtedly more frustrating than satisfying.

The one reform that might have fundamentally altered the internal organization of the prison, Osborne’s Mutual Welfare League, was not implemented to any degree at all. The League persisted for a few years at Sing-Sing, but a riot in 1929 gave guards and other critics the occasion to eliminate it. One couId argue that inmate self-rule under Osborne was little more than a skillful exercise in manipulation, allowing Osborne to cloak his own authority in a more benevolent guise. It is unnecessary, however, to dwell on so fine a point. Wardens were simply not prepared to give over any degree of power to inmates. After all, how could men who had already abused their freedom on the outside be trusted to exercise it on the inside? Administrators also feared, not unreasonably, that inmate rule would empower inmate gangs to abuse fellow prisoners. In brief, the concept of a Mutual Welfare League made little impact on prison systems throughout this period.

If prisons could not approximate a normal community, they fared no better in attempting to approximate a therapeutic community. Again, reform programs frequently did alter inherited practices but they inevitably fell far short of fulfilling expectations. Prisons did not warrant the label of hospital or school.

Starting in the 1910’s and even more commonly through the 1920's, state penitentiaries established a period of isolation and classification for entering inmates. New prisoners were confined to a separate building or cell block (or occasionally, to one institution in a complex of state institutions); they remained there for a two- to four-week period, took tests and underwent interviews, and then were placed in the general prison population. In the Attorney General’s Survey of Release Procedures: Prisons forty-five institutions in a sample of sixty followed such practices. Eastern State Penitentiary, for example, isolated newcomers for thirty days under the supervision of a classification committee made up of two deputy wardens, the parole officer, a physician, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, the educational director, the social service director, and two chaplains. The federal government’s new prison at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, opened in 1932 and, eager to employ the most modern principles, also followed this routine. All new prisoners were on “quarantine status,” and over the course of a month each received a medical examination, psychometric tests to measure his intelligence, and an interview with the Supervisor of Education. The Supervisor then decided on a program, subject to the approval of its Classification Board. All of this was to insure “that an integrated program . . . may lead to the most effective adjustment, both within the Institution and after discharge.”

It was within the framework of these procedures that psychiatrists and psychologists took up posts inside the prisons for the first time. The change can be dated precisely. By 1926, sixty-seven institutions employed psychiatrists: thirty-five of them made their appointments between 1920 and 1926. Of forty-five institutions having psychologists, twenty-seven hired them between 1920 and 1926. The innovation was quite popular among prison officials. “The only rational method of caring for prisoners,” one Connecticut administrator declared, “is by classifying and treating them according to scientific knowledge . . . [that] can only be obtained by the employment of the psychologist, the psychiatrist, and the physician.” In fact, one New York official believed it “very unfair to the inmate as well as to the institution to try and manage an institution of this type without the aid of a psychiatrist.”

Over this same period several states also implemented greater institutional specialization. Most noteworthy was their frequent isolation of the criminal insane from the general population. In 1904, only five states maintained prisons for the criminally insane; by 1930, twenty-four did. At the same time, reformatories for young first offenders, those between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five or sixteen and thirty, became increasingly popular. In 1904, eleven states operated such facilities; in 1930, eighteen did. Several states which constructed new prisons between 1900 and 1935 attempted to give each facility a specific assignment. No state pursued this policy more diligently than New York. It added Great Meadow (Comstock), and Attica to its chain of institutions, the first two to service minor offenders, the latter, for the toughest cases. New York‘s only rival was Pennsylvania. By the early 1930’s it ran a prison farm on a minimum security basis; it had a new Eastern State Penitentiary at Grateford and the older Western State Penitentiary at Pittsburgh for medium security; and it made the parent of all prisons, the Eastern State Penitentiary at Philadelphia, the maximum security institution. Some states with two penitentiaries which traditionally had served different geographic regions, now tried to distinguish them by class of criminals. In California, for instance, San Quentin was to hold the more hopeful cases, Folsom the hard core.

But invariably, these would-be therapeutic innovations had little effect on prison routines. They never managed to penetrate the system in any depth. Only a distinct minority of institutions attempted to implement such programs and even their efforts produced thin results. Change never moved beyond the superficial."

- David J. Rothman, Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternatives in Progressive America. Revised Edition. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 2002 (1980), p. 128-134

#penal reform#progressive penology#progressive politics#rehabilitation#penal modernism#american prison system#penology#prison sports#prison community#prison discipline#convict uniforms#prison routine#classification and segregation#history of crime and punishment#mutual welfare league#utopia of classification#academic quote#reading 2023#david rothman

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

imagine not being able to be critical of the push towards transition by medical professionals who profit from it or the gender stereotypes and homophobia that give place to that social transition WITHOUT being an absolute freak towards trans people who are quite literally just living their life. deranged.

#imagine acting this way and yet thinking you're any different than those making hate campaigns against trans people based on homophobia#religious fanatismn and sexism#who believe not conforming to gender customs is unnatural. idiotic behavior#imagine making it a whole crusade against trans and often just gender nonconforming people and having the gal to claim it's about feminism#to this day ive never seen a logical argument about trans PEOPLE being a danger to women as a whole#outside of the absolutely abnormal situation of american prisons having the most dangerous self identification policies#which is an IMPORTANT but very specific problem#not quite warfare on behalf of trans people#but a prison system that is already violent as it is

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The question of whether prison is now an obsolete institution has become particularly urgent in light of the fact that more than two million people in the United States (out of a world total of nine million) currently populate prisons, penitentiaries, juvenile institutions and detention centers for immigrants. Are we willing to relegate ever-increasing numbers of people from racially oppressed communities to an isolated existence characterized by authoritarian regimes, violence, disease and technologies of confinement that produce severe mental instability?

According to a recent study, prisons house twice as many people with mental illness as all psychiatric hospitals in the United States combined. When I started working on anti-prison activism in the late 1960s, I was baffled to learn that there were nearly two hundred thousand inmates. If someone had told me that in three decades the number of people locked up in cages would have increased tenfold I would not have believed it. I think my reaction would have been something like this: "However racist and undemocratic this country may be [remember that during that period the demands of the civil rights movement had not yet materialized], I do not believe that the government of the United could never lock up so many people without unleashing powerful public resistance. No, it will never happen, unless the country falls into fascism ».

That could have been my reaction thirty years ago. The reality is that we would have been called to usher in the 21st century by accepting the fact that two million people - a group larger than the population of many countries - spend their lives in places like Sing Sing, Leavenworth, San Quentin and Alderson Federal Reformatory. for Women. The gravity of these figures is even more evident when we consider that the overall US population is less than 5% of the world total, while the United States can boast more than 20% of the entire prison population. In the words of Elliott Currie, “prison has become a looming presence in [American] society to an extent unprecedented in our history or in that of any other industrial democracy. With the exception of the great wars, mass incarceration represented the social program most fully implemented by governments today".

Angela Davis

Photo by Leonard Freed - 1963

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s hardly a secret that the country has been experiencing a shortage of locksmiths, welders, and turners for a very long time. And now Russia just doesn’t have enough workers to manufacture missiles and tanks for Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Uralvagonzavod, the largest tank manufacturer in the country, failed to hire enough workers, even the unskilled, and has no choice but to use convicts to fill the gap. Hundreds of prisoners from a penal colony in the Sverdlovsk region will soon be sent to Uralvagonzavod.

[…]

Since Putin’s plan to win a short military war in Ukraine has visibly failed, Russia is getting ready to wage a long and devastating war in Ukraine. To do so, it must adjust the economy to the new conditions and increase weapons production. Many military plants and manufacturers have been working around the clock for months now, but still cannot satisfy the growing demand without new supplies of workers. Russia’s prison population of 450,000 provides a potentially large number of unskilled workers.

#now watch the self-proclaimed ''socialists'' who were crying murder about american prison system ignore ths#russia#war in ukraine#prison system

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slate Magazine: Helen Vera: Against Solitary Confinement: State are Finding it's Impractical as well as Immoral

Source:The New Democrat

The current use of the process of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons is deplorable. There are no guidelines relating the length of confinement to severity of offense. The process is used at the discretion of onsite officials. This results in wide variations with some cruel and counterproductive results. Indefinite solitary confinement is simply inhumane and can only…

View On WordPress

#2014#America#American Corrections System#American Prison System#Cruel and Unusual Punishment#Extreme Solitary Confinement#Helen Vera#Solitary Confinement#United States

0 notes

Text

Individuals released from these kinds of institutions are a genuine danger to society.

"Humankind: A Hopeful History" - Rutger Bregman

0 notes