#and i have already found a book on the subject i wanna read now 👀

Text

“Five Hundred Eyes”

Season 1, episode 16 - 7th March 1964

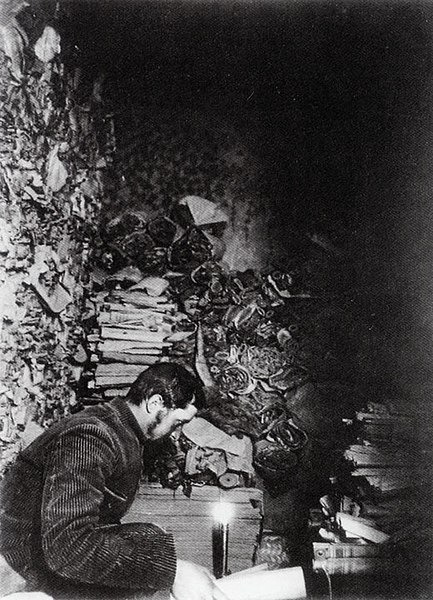

[id: French orientalist Paul Pelliot examining a manuscript in the Library Cave of the Mogao Caves (the Caves of a Thousand Buddahs). He is sat on the floor, and around him are stacked many other manuscripts and books. /end id]

Okay, this review was going to be the part where I talked enthusiastically about the genuine attempt to depict Chinese culture in this serial, maybe talk about the lovely sets, and centre the entire discussion around Ping-Cho’s story in the middle of the episode. Fortunately, I decided to do some research around that story before writing it. You will see why I needed to do research and this may end up being a bit long and a bit of a rant but hey, I’m a history nerd and I don’t want to misrepresent anything, and I now have a lot of opinions about how John Lucarotti went about crafting a historical story. We’ll get there.

Is it an entertaining watch: 3/5, yeah, not much happens but I love the production and while watching it this was the point where I started to like this serial. Upon further research, I don’t any more.

Does the production hold up: 2/5, again, yellowface, but some of the sets in this serial are really nice, althought the Cave of Five Hundred Eyes itself really looks like shit from what I can tell.

Does it use its time well: 3/5, the first half drags a bit in a way that feels like it’s trying its hardest to move on, but by the middle it’s settled into a slow pace that feels deliberate, with time for Ping-Cho’s story (we get there when we GET there, I’m saying nice things at the moment) and the slow build-up of the threat at the end leading to the cliffhanger (more on that side of the story tomorrow).

Are the characters consistent and well-used: 4/5, yeah, they all get something to do, and there’s at least one fun or interesting scene for each of them. I saw some reviewers complain that Ian giving out fun facts about etymology

Is there anything actually going on under the surface: 1/5, as will become apparent, I suddenly don’t have much faith that John Lucarotti put any thought at all into this serial, and just wanted to put to screen as many things that Marco Polo said happened as possible.

Does it avoid being a bit dodge with its politics: 1/5, ah, and now we get to the good stuff. And by that I mean that bad stuff. I’m gonna have to actually organise this into paragraphs to properly explain what I mean.

As I mentioned earlier, in roughly the middle of the story, Ping-Cho tells a story about the Cave of Five Hundred Eyes, in which “Ala-eddin, the Old Man of the Mountains” uses “devious schemes” and the hashish drug to trick his soldiers into believing they were in paradise, then using that faith to convince them to give their lives for him, or else they would never see that paradise again, as only he had the power to take them there. Then, “mighty Hulagu” besieged their “lair” for three years, before killing them.

In my initial outline for this review, I praised the writing and production for giving the only actually Asian actor the monologue in which she tells a story from her culture and history. Unfortunately, upon even the smallest amount of research (I only had a day to write this, but I spent several hours reading various wikipedia articles and their sources to confirm this), I learned that this story isn’t a traditional Chinese legend about the Hashshashin, nor is it an accurate historical source. It is something that Marco Polo and other European scholars believed, as Marco Polo himself documented the story himself and is one of the original sources, but its authenticity has been thoroughly debunked.

The real history is that of the conflict between the Mongol empire, under Möngke Khan and Hülegü Khan, and the Nizari state of Alamut, ruled by Alā ad-Dīn Muḥammad, in which 100,000 Nizaris were massacred by the Mongols. However, this part is not the focus of Ping-Cho’s story, more of an afterthought and an explanation for why they aren’t around any more. The bulk of the story revolves around the story of The Old Man of the Mountains, which has a complicated history too. The real “Old Man” was Hasan-i Sabbah, founder of the Nizari Isma'ili state in c.1090 and its fida'i military group, who would eventually gain the name “Assassins”. The origin of this name for the group is disputed, but it’s not because of the hashish drug, Ian.

The most compelling piece of evidence I found against this story of the Nizari fida’i was that of Peter Willey, who argues that according to the esoteric doctrine of the Nizari, the Isma’ili understanding of paradise was spiritual, not simply physical. Therefore, they would not have been fooled by a pretty garden and hot women into believing they were in paradise, or that only Hassan-i Sabbah was able to get them there again. Willey also points out that Juvayni, courtier of Hulagu Khan, surveyed the Alamut castle where the Nizari were, and found no evidence of any garden - and given how Juvayni destroyed texts in the library he deemed heretical, it would be surprising if he saw the drug use and temptation of this supposed garden and didn’t make note of it.

So if, even in contemporary non-Ismaili Muslim sources which were hostile to the Ismailis, there is no evidence of this story or any link of hashish to the Assassins, where did this come from, and why did John Lucarotti put it here? Well, that’s part of a long history of orientalism that I don’t have the time, energy, or knowledge to get too deep into, but I’ll give it my best shot.

The Nizari fida’i soldiers were known for not fearing injury or death, and the Crusaders, being the Crusaders, didn’t understand how they could be so loyal to their cause as to throw their own lives away (one story of similarly dubious origin describes them literally throwing themselves off cliffs at the order of their commander, as proof to an enemy leader that they were more loyal and therefore dangerous than the other larger army).

The term “hashishi” was used by 1122, with derogatory connotations of outcasts and rabble, to refer to the Nizaris, by their enemies, the term having its origin describing criminals who were mentally absent, and therefore similar to the effects of the hashish drug. However, no evidence points to the drug being used by the Assassins, or there being a link to the word being used for them and the taking of the drug, not even from the anti-Isma’ili Muslim sources at the time. However, the Crusaders and other Europeans at the time didn’t know this, which is why Marco Polo describes a legend involving the drug.

The fear of the Isma’ili as deadly, radical, and bloodthirsty assassins was linked to the hashishi term and therefore the hashish drug, and also to William of Tyre’s “Old Man of the Mountain” description of the Isma’ili leader at Alamut, and was filtered through various orientalist tropes around the secret practices of the Nizaris created by Crusaders ignorant of Islam, and through the 12th and 13th centuries this combination become a legend similar to that which Ping-Cho describes. These stories were popularised in the 19th century by orientalists such as Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, and presumably through these sources, along with translations of Marco Polo’s writings, eventually reached John Lucarotti.

Now, my first instinct after learning all of that was to think “ah, but it was the 1960s! The main book that you looked at was published in 1995, there just wasn’t much research put into this by the 1960s.” And while yes, there wasn’t as much research, there was still some. Modern Isma'ili scholarship, pioneered by historians such as Vladimir Ivanov at the Islamic Research Association in the 1930s and 40s, laid the groundwork for disproving these legends, and all of that could have been researched by Lucarotti when writing this. Now, maybe he didn’t think to check that Marco Polo wasn’t 100% right about everything, or maybe the intention was to provide a depiction of Marco Polo’s perspective on ancient China, or maybe Lucarotti thought that since this legend was around at the time, telling it in the story was historically accurate. However, I think all of this is giving Lucarotti too much credit. I think what happened is he read Marco Polo’s diaries, and adapted stories into this Doctor Who serial, and then, despite this being a supposedly educational show, didn’t think any more of it, resulting in an uncritical regurgitation of orientalist tropes and etymological misnomers that had me fooled into thinking he was providing an accurate depiction of this culture and time period. Ugh.

Overall Score (oh yeah this is a Dr Who review not a history essay) - 14/30

#i would like to apologise for any innacuracies i end up with trying to correct this 60 year old episode#i am just one woman and sourced most of this from wikipedia in one day. sorry im bound to get things wrong but im trying here#and i have already found a book on the subject i wanna read now 👀#anyway we'll see if i have enough energy to do this much thinking about the aztecs in a few weeks. we'll see.#doctor who#dw#first doctor#orientalism#dw review#ian chesterton#barbara wright#susan foreman#historical#marco polo#over a thousand words on one scene from one episode. god. autism.#11-15#was tempted to give it a zero in the last category but im not breaking my system for comic effect THIS early its week 3 ffs#season 1

7 notes

·

View notes