#blagoje marjanovic

Text

1945 - The Year Tito Changed Football

In a continuation of an occassional series on Yugoslav football history, we now look on how the end of World War Two changed the face of fooball in the region forever as football, war and communism found that the old way of doing things simply could not hold...

History is written by the winners and, in one of the most violent theatres of World War Two, the victorious Communist forces led by Josip Broz Tito were not in an especially forgiving mood for those who collaborated either with the Nazis or the puppet state run by the Ustase and that didn’t just include those working in the government or those at death camps such as Jasenovac, it included football clubs.

“Football clubs?!”, you may exclaim. But during World War Two, the puppet Croatian state set up its own league, the short lived Championship of the Independent State of Croatia, a name containing two precise half-truths: Croatia was hardly independent and the borders of the state didn’t actually correspond with what we would understand as Croatia today - Split, for example, was part of Italy with large swathes of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina including Sarajevo and Mostar as part of the state and it stretched almost to Belgrade at its greatest point. Much the same sort of league was seen in Serbia while clubs in fully occupied areas sometimes joined their new nation’s league also. Some of these clubs would leave successors that are still recognisable names today. Some would disappear altogether. All would have a major part to play not just in interbellum Yugoslavia, but during World War Two itself.

And all would find themselves on the receiving end of the Tito regime’s thirst to wipe out all traces of the Axis in Yugoslavia.

“The Disputed Legacy”: SK Jugoslavija

When is a successor club not a successor club?

It’s a very difficult question to answer, particularly when that successor club doesn’t want anything to do with their predecessors. Yet that’s exactly what happened to SK Jugoslavija, Serbia’s first ever footballing champions. Set up in 1913 as SK Velika Serbia (transforming into SK Jugoslavija after World War One), they won the Olympic Cup, the first organised championship in the country’s history in 1914 and, as you may be able to guess by that year, the only time the Olympic Cup ever actually happened given football would be suspended during World War One.

Jugoslavija would then become Serbian champions once again in 1921-22 which would, as with the Olympic Cup, be the last time that competition would ever be contested before the Yugoslav championship began the following year. The club would then go on to win the second and third editions of the Yugoslav Championship (Note 1).

This success would wane as the Twenties went on as the club built and then expanded a new ground and the assorted costs around that made them less competitive albeit still good enough to finish second in 1930 and 1935. In terms of history, they would host the first ever floodlit game in Yugoslavia in 1933 and they would send three players to the 1930 World Cup.

But what of this disputed history?

To that we must first start in 1938 and the plans to expand the club into a larger sporting society and, with that, expand the stadium, with running track, to accommodate 50,000 people as an almost exact copy of Berlin’s Olympic Stadium. This project would come to almost completion on the outbreak of war - the end date for the stadium was 20th April, the Luftwaffe started bombing Belgrade on the 6th. As such, Jugoslavija were forced to play on this nearly finished shell of a ground and continued to take part in the Serbian League operated by the puppet government installed by the Nazis, winning the title in the 1941-42 season, the first of three seasons under the occupied government (Note 2).

In December 1944, the clubs which co-operated with the puppet regime were dissolved (finalised the following May) and, around two months later the Serbian Anti-fascist Youth League decided to set up a sporting arm which would eventually become Crvena Zvezda (Red Star Belgrade) and the club would be handed the assets and colours of SK Jugoslavija including the now finished Avala Stadium (Note 3). Many Zvezda fans deny that the club is a successor of Jugoslavija due to the vastly differing ideologies between Jugoslavija, the club viewed as fascist collaborators, and Crvena Zvezda, who immediately became embedded in Serbian nationalist and worker culture.

Whether you subscribe to the idea that Zvezda are the successors of Jugoslavija or not, what’s impossible to deny is that Crvena Zvezda owe them a debt for immediately making them one of Serbia’s premier clubs and, in doing so, setting off 70+ years of history that have helped define not just Serbian, but European, football.

“The Old Romantics” - BSK

One club which doesn’t have a disputed legacy is OFK Beograd. OFK were regular European competitors in the Fifties and Sixties during their Golden Era and had continued success even after 2000. They now reside in the altogether more humble surroundings of the Belgrade League in the Serbian pyramid but once went as far as the Semi Final of the Cup Winners Cup in 1962-63.

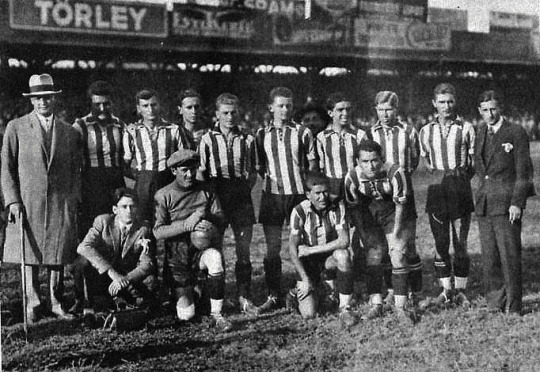

But go further back, and an even more illustrious history reveals itself. Originally founded in 1911 as Belgrade Sport Club (BSK), the club were the most dominant side in pre-war Yugoslav football. Five titles in the Thirties, driven by arguably the greatest forward line Serbia ever produced in Blagoje Marjanovic and Aleksandar Tirnanic who both played over 500 games for BSK and both who scored at a rate higher than 1 per game at club level. BSK would make each of them Yugoslavia’s first ever professional footballers.

But of more note would be the BSK would define the location of football in Belgrade. Owing to post-World War One food shortages, their original stadium was getting ploughed for crops in the off-season in their original location of Trkaliste. However, the geography of Belgrade was changing and, with an influx of people contributing to rapid urbanisation, Trkaliste soon had more value as a public area than as a football stadium. SK Jugoslavija moved early while BSK took time to plan and came up with an idea which revolutionised the rivalry between Jugoslavija and BSK - they would move to Topcider Hill, under half a kilometre from Jugoslavija’s stadium.

And from some standpoints, the stadium itself was revolutionary in introducing new methods of stand layout and construction to Western norms that were otherwise alien to the region. Post-war, OFK would not receive that particular asset, it would instead be levelled and rebuilt as the JNA Stadium in which Partizan reside to this day, but it stood as a representation of Belgrade’s growth from provincial hub to modern European city and would stoke the fires of one of football’s greatest rivalries.

Post-World War Two, the club would be dissolved but rebuilt as Metalac by former members of the BSK hierarchy, changing name back to BSK and then, eventually, to OFK - the Romanticari, named as such for their beautiful football from their golden era. Not for they the Eternal Derby, simply the Small Derby against Rad.

Their history, however, remains.

“The Splitters” - NAK Novi Sad

Nowadays, Novi Sad is known solely for Vojvodina but, prior to the end of World War Two, they were merely the pre-eminent club with NAK. Uniquely, Novi Sad was a city split down ethnic lines between not Serb and Croat, as much of Yugoslav conflict has often been framed, but between Serb and Hungarian populations. Vojvodina, still with us to this day, were the club of the Serb population, but different demographics brought their own clubs of which NAK were that of Hungary (Note 4).

Success was limited, only appearing in Yugoslavia’s premier competition once, in the 1935-36 season reaching the Semi Final stage (Note 5). It was during the war, however, that they would become notable for all the wrong reasons.

In 1941, the Axis invaded Yugoslavia and split it into several parts. Allied with the Axis, Hungary did their part and invaded northern Serbia, with Novi Sad representing it’s most southernly reach. Vojvodina were outlawed and Novi Sad itself was the venue for one of the most brutal retributions of the entire war.

In early 1942, a small resistance force were surrounded at a farm and wiped out, taking ten Hungarian soldiers with them. Immediately, punitive measures were put in place. Novi Sad was surrounded and Hungarian forces made their way through the city street by street, firstly hunting for resistance sympathisers but then anyone they could get their hands on. Over three days, thousands were imprisoned and interrogated with an estimated 1,283 killed in Novi Sad city alone and over 4,000 in total in the area during the raid. The message from Hungarian forces was clear - comply or die.

Six Vojvodina players chose the latter and joined NAK, for various reasons. Most notable among these was Yugoslav international Ivan Medaric (note 6). Medaric’s dilemma had been fairly simple - he was a long term member of the Yugoslav Communist party and had already been imprisoned for political activities while a student - he knew full well he would be high up on any list for punishment and so had no choice but to go along with the occupiers. NAK would change their name to Ujvideki AC, committing to their Hungarian identity and, more controversially, extending that to players in a forced Magyarisation - Ivan Medaric became Ivan Mezes, for example. When Axis control of the area crumbled, so too did the Hungarian leagues and NAK (or UAC, as they were in the Hungarian league) were disbanded.

NAK’s experience showed more than any just how much fascism bent football to it’s will during this period. Where other collaborationist clubs merely kept on playing, NAK changed their name and subjugated other clubs to its will with, most notably, Vojvodina split between players who moved to NAK, those who simply went out of football and those who died fighting to overhaul Hungarian rule.

In the long run, NAK’s excesses turned Novi Sad into a one club city and, when the war ended, Vojvodina returned to fill that vacuum and, in doing so, swiftly became one of Yugoslavia’s great clubs.

“The Resurrection” - Slavija Sarajevo

Sometimes, avoiding being seen as collaborating with the occupation wasn’t enough to avoid dissolution. Slavija, inactive during the Nazi occupation, were still put out of existence and their stadium given to both FK Sarajevo and Zeljeznicar, both created out of aftermath of World War Two.

It was a surprising fall for a club which had been by far the most successful club in Bosnia prior to the war and one which seems to have been wiped out for little reason other than a bureaucrat fancied doing it. But Slavija’s history was never exactly straightforward.

When Slavija were founded in 1908, their small scale story was played out against a much more dangerous backdrop - the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia which, due to a ban on communal gatherings imposed in the aftermath, meant that meetings of the club were sporadic at best. In 1909, they would start their first regular sessions, dragging goalposts along to a park as football was new to the city and no other facilities available.

Through their first years in the run up to World War One, the Balkans were a tinder box due to emergent nationalism combining with the militarising Empires around it in Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans, both reacting to their own slow, lingering deaths. This would erupt in the Balkan Wars in 1912/13. The success of Serbia and other new states in those conflicts would light a fire under nationalism in the Austro-Hungarian empire and, in turn, set off a crackdown by authorities.

For Slavija, what that meant was that the ethnic Croats within the club would split and form their own club (Note 7) and that life would be made hard for them in the run up to opening a stadium in Curcic Vila at the end of 1913.

Within six months, Gavrilo Princip fired the shot that sent the world into war. Slavija would go dormant as most members would be conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army. Curcic Vila itself would be burned to the ground in riots in the immediate aftermath of Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s death.

Once the war was over, Slavija came back with renewed vigor debuting in the Yugoslav championship in 1924 with a 5-2 loss to SK Jugoslavija. SASK would take that place the following 4 years with Slavija getting back into the region’s top competition in 1929. From there on, Slavija would be a near permanent feature of the league. Their high point would be the 1935-36 season, when the competition went back to a cup format after years as a league. In this edition, they would get past Crnogorac Cetinje, Gradanski Skopje, NAK Novi Sad before meeting BSK in the final. The two legs would see only one goal as BSK won the championship.

During World War Two, the club shut down once more (Note 8) but, at the end, the communist authorities disallowed them and their ground given to Zeljeznicar and Torpedo (now FK Sarajevo). Once Yugoslavia split, Slavija would reform in 1993, qualifying for Europe twice in the 2000s.

“The Giants” - Gradanski Zagreb

And so we end where this piece began - a massive club, arguably the region’s greatest during the interbellum, taken apart once the war was over and rebooted as a club we would recognise as arguably the region’s biggest now. So SK Jugoslavija became Crvena Zvezda, so did Gradanski Zagreb become Dinamo. No team would win more titles in between the wars and they, along with neighbours HASK and Concordia, would turn Zagreb into Yugoslavia’s footballing powerhouse in the interwar period.

Gradanski were formed out of Croatian nationalism in 1911 - rumours that a Hungarian club would be set up in Zagreb spurred Gradanski to be set up by Andrija Mutafelija (Note 9) and the club grew quickly, with a rivalry growing with HASK quickly due to HASK coming from the middle class and Gradanski coming from the working class (Note 10).

With Zagreb having such a healthy footballing scene, Gradanski rapidly grew and were immediately competitive in the Yugoslav Championship when it was set up in the 1920s and their rivalries immediately became less local - Hajduk Split, BSK and Jugoslavija would become the big games as the championship became dominated by Croatia and Serbia. They would win the first Yugoslav title and follow it up by moving to a new stadium, Koturaska (Note 11), where they would stay and which would become Dinamo’s first home.

Gradanski, more than most, would see their players impacted by this rivalry. In 1919, the Yugoslav FA was set up in Zagreb but 10 years later it would move to Belgrade. The result would be Croatian players boycotting the Yugoslav national team missing the first World Cup (Note 12).

They would also pioneer foreign coaches - that first Yugoslav title would be won with an Englishman, Arthur Gaskell, in the dugout. Details are sketchy (Note 13), but it is believed that he played for Bolton and Macclesfield in the first decade of the Twentieth Century before bouncing around Eastern Europe eventually settling back in Rochdale. Irishman James Donnelly would also manage the club in the 1930s. Gaskell would take the team abroad also with what is thought to have been his last game at the club being a win in Barcelona against FC Barcelona themselves.

Gradanski would enter World War Two perhaps at their greatest - in 1936, the club would demolish Liverpool 5-1 in the club’s first ever loss to European opposition before travelling to Edinburgh and drawing with Hearts. They would win the last edition of the Yugoslav championship pre-war, fired to titles by the talents of August Lesnik who scored at a rate of a goal a game in the four seasons prior to the War, including a hat trick within 7 minutes against BSK. The team was full of Yugoslav internationals - 9 of the 11 that won that last Yugoslav title were capped and would become the spine of the short lived Croatian national side during World War Two (Note 14).

During the war itself, they unsurprisingly dominated the Croatian championship, winning two of the three seasons played, coming second in the other. When the war ended, they were dissolved, but Dinamo would be set up as a direct successor taking most of Gradanski’s players (and a few of HASK’s) and all of Gradanski’s fan base. Dinamo would go as far to changing their badge in 1969 to a carbon copy of Gradanski’s.

No club saw an attempt to wipe it out of existence than Gradanski, yet no club that was dissolved lives on with as great a shadow as Gradanski.

Note 1 - The Yugoslav First League didn’t actually turn into a league until the 1927 season. The years prior to this, the championship was fought out in a straight knockout format which, arguably, makes winning two in a row even more impressive.

Note 2 - Two and a bit seasons, really. The third season was abandoned half way through owing to Allied bombing and, eventually, liberation.

Note 3 - This would, eventually, become the Marakana. In the late Fifties, the Avala was closed for safety reason as the stands were unstable due to rotten beams and was knocked down and the Marakana partially dug into the ground it stood on as it ran vastly over time and over budget.

Note 4 - Also of note were Juda Makabi, the Jewish club which dropped off the map just prior to World War Two, and Macva Sabac, from the neighbouring country, who survive to this day.

Note 5 - This would be the last season that the Championship would be decided in a Cup format. NAK would be the only semi finalists from this season not to be included in the league the following year.

Note 6 - Medaric’s big claim to fame? He was the scorer of the first ever goal for Dinamo Zagreb. He would leave NAK to join the resistance in 1943.

Note 7 - This would become SASK, who were Bosnia’s second most successful club prior to World War Two. They, too, would be dissolved at the end of the war - in their case for playing in the Croatian league during the war.

Note 8 - There genuinely appears to be no explanation for this as far as I can tell. The best explanation I can muster is that, as SASK were disbanded then Slavija were simply to keep balance and avoid aggravating ethnic tensions in the city. Having Zelje and Torpedo as two clubs based outside the original ethnic orientation of clubs in the city helped keep the peace in what was a febrile mix of Bosnians, Serb refugees and Croats. If nothing else, Tito was one to try to cool nationalism as opposed to those who weaponised it after his death.

Note 9 - Mutafelija is one of the fathers of Croatian football - he played for PNISK (now NK Zagreb) on foundation becoming one of Croatia’s first footballers then setting up Gradanski and running the club prior to World War One.

Note 10 - HASK were known as Akademicari, which requires no translation. As a larger sporting organisation, bits of it still survive, specifically in Water Polo and Volleyball. HASK’s home ground was none other than Maksimir, handed to Dinamo after World War Two. Dinamo are most obviously linked to Gradanski due to the image of both clubs, but Dinamo equally owe a debt to HASK for their foundation. Their strip and colour combo also made them look very much like a Croatian Motherwell.

Note 11 - Koturaska would be opened by none other than Stjepan Radic. Radic is, more or less, the most notable Croatian politician of the entire 20th Century - he would be assassinated in parliament in 1928 by the serb Punisa Racic. His Martyrdom sent Yugoslavia into dictatorship, was used as justification for mass killings of Serbs during the Holocaust by the Ustase, an image of liberation during the Croatian Spring and has more streets in Croatia named after him than any other figure.

Note 12 - How important was this? Gradanski provided six players to the 1928 Olympics squad, had four current internationals at the time and would see four more players called up to the side immediately following the conclusion of this dispute. Most notable of the missing players was Aleksandar Zivkovic, then of Concordia in 1930 who was one of the league’s top goal scorers and would become a diplomat of Croatia to Nazi Germany during World War Two. Also of note would be Danijel Premerl (29 caps for Yugoslavia around this time) and Gustav Lechner (44 caps starting as soon as the dispute was over).

Note 13 - Gradanski, HASK and Concordia weren’t just dissolved. Unlike the Belgrade clubs where there is still plenty of evidence as to what went on before 1945, the Zagreb clubs saw their records and paperwork burned. As such, pre-1945 information is bare bones at best as these teams had their existence more or less wiped from the earth. An Arthur Gaskell definitely managed Gradanski and Macclesfield’s archives show that he did go to Eastern Europe, but the detail is regrettably lacking.

Note 14 - Including Florian Matekalo, the first ever goalscorer for both Croatia and then Partizan Belgrade (which deserves a raised eyebrow, all things considered), Milan Antolkovic, probably the only footballer ever to represent his country both in football and in table tennis and Milan Danic, a Serb playing for Croatia who would play a game vs Nazi Germany in Vienna and then be executed as soon as he returned to Zagreb.

0 notes