#boqta

Text

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

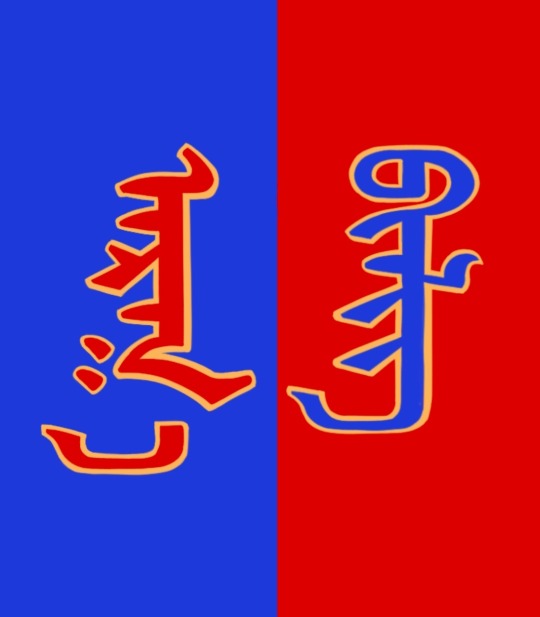

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miss Grand Mongolia 2022 National Costume -“THE LEGACY OF GARID”

This headpiece tells about the greatness and glory of the Mongolian.

Where were born the strong, brave and big-hearted Mongolian sons and daughters.

This headdress has 3 elements that have their own meaning, namely the "The Crystal Tower", "The Wings", and "The Crystal strings".

"The Tower"

This section is inspired by the traditional shape of the Mongolian women's hat, namely the "Boqta".

The hat is a pride and can show the social status of the wearer.

This time we took a shape resembling a tower from boqta and combined it with a crystal element (which resembles an ice shard).

The crystal tower depicts a Mongolian woman who is brave, tough and honorable.

"The Wings"

Inspired by the story of Khan Garid who is a proud partner of Genghis Khan.

Garid (Mongolian: арьд) is a Mongolian word corresponding to the Sanskrit Garuda with several connotations related Mongolian culture. The Garuda is a large mythical bird-like creature or humanoid bird that appears in both Hindu and Buddhist mythology. Garid is a rank in traditional Mongolian wrestling meaning "mythical bird" as well as the name of the pet eagle of Genghis Khan.

-Wikipedia-

A symbol of vision, mighty, authority, and courage.

"The Crystal Strings"

Describing the beauty of winter in the Mongolian land, where the Mongolia have a long cold climate.

“Beautiful Winter in The Land of Mongolia”

#miss grand international 2022#miss grand international#national costume contest#she looked like a queen#pageant#miss grand mongolia#there are other videos showing how intricate the headpiece is and i have no clue how she managed to balance it

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lovely modern reproduction of the famed Mongol boqta (bohkta, boqtaq). If you the accounts of non-Mongol authors discussing their encounters with Mongol culture, if they discuss Mongol women, will almost always mention the boqta.

Was the origin of the cone-shaped princess hats of western Europe? I can't say. I've heard the claim several times, but not with evidence to back it up. They certainly share a similar idea and structure, but clothing styles transmitted by cultural exchange is a tough thing to pin down in a medieval context. If anyone has any thoughts or knowkedge on that matter, I'd love to hear it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empok Nor AU where instead of making Garak murderous, the drug makes him amorous. Like out of his mind affectionate and wants to make love to everybody sort of amorous. Especially O’Brien, being that he’s the most worthy mate or whatever. Garak gets sent off to work with Amaro and Boqta so that he’ll leave the Chief alone but then he just ends up seducing Amaro instead and causing his divorce.

#The other two Cardassians aren’t a problem cuz they’re off somewhere else#declaring their undying love#elim garak

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Primer for the Non-Subscriber: The Conical Hat

"You can choose a ready guide, in some celestial voice.

If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice.

You can choose from phantom fears, and kindness that can kill.

I will choose a path that's clear, I will choose free will."

~Neil Peart

Let us delve into WHY “Black Hat Society” was chosen.

Come, take a walk with me through the words of history. Our first stop will be short, here is the “why” for color.

By definition, “black” is the absorption of ALL colors in the visible spectrum. The CONES in our eyes perceive this as “nothing” being reflected or refracted from something. All light is absorbed by that thing (Newton’s). This is perceived as a ONENESS to me. ALL things are absorbed because all things are as one. Furthermore, I do not subscribe to any preconceived notions or prejudices forced upon society over time. With that, I am neither a Theist nor Atheist. I believe there is a little #TRUTH in ALL THINGS. Even something that only exists in thought, “is”. That which is not perceived, or does not exist in thought, “is” too.

I digress. Let us talk more about the history of this millinery success. This hat has traveled through human existence for thousands of years. The conical black hat has carried with it meanings of power, both positive and negative. Most recently, a hat of this style (conical black felt) was discovered on mummies from around 4,000 years ago with the “Subeshi Witches”, found on the northern Silk Road trade route. (Although, we now understand that those around the World who were known as “witches” often did not even cover their heads or wore simple scarves instead.)

Before 1000 BC, also known as the Bronze Age, priests (because this title has ALWAYS referred to “elder” , “one with knowledge” or “wise one”) would wear golden conical hats that stood almost 3 feet tall. These hats were decorated with sun and moon symbols, indicating that their wearers were star-trackers who were able to analyze the sky to study celestial bodies and predict the weather. This is not such a mystery today. Seeing the power these people commanded from others around them by simply paying attention to their environment, dogma was taking notice.

Did the “Three Wise Men” derive from here? Was a conical hat worn to the birth of this particular messiah? They did follow a star after all.

None the less, their meteorological ability, misunderstood by many, caused the priests to be referred to as “king-priests” and were thought to have magical powers. It was also believed that they had access to a divine knowledge that enabled them to look into the future. Much of this was simply the ability to follow “cause and effect”. It is from this early use of conical hats that led to the traditional star-spangled wizard’s hat that we recognize in clothing today.

There was some thought of the Babylonian Jews at this time wearing conical hats themselves by choice. Possibly a conquered people from Iran? Scythian? Their warriors were described as wearing “conical hats” from cuneiform inscriptions found from that time. Regardless, they were forced to then wear them as a form of discrimination from the Islamic groups of Iraq. This “public identification” carried on for thousands of years for anyone connected to this hat.

Jump forward in time to the “Christ Era”.

In the 6th to 10th century, also referred to as The Dark Ages (the first half of the Middle Ages from 500 to 1000 AD) not a lot of history was able to be kept. This was a very volatile time during human existence. The Roman Empire fell and a lot of writings and knowledge were lost to the ages. The collapse of the Roman Empire lead to a lack of a kingdom or any political structure. This caused the churches of the time to take control and they became the most powerful institutions in Europe. It was during this time the Church began taking elements of “heathen” culture and Old Religion to appropriate for their agenda of conquer and expand.

Turning to the 11th century, the conical hat seemed to have been morphed into use as the Mitre, an accessory vestment, by the Church. There is quite a debate about this. You can observe from various timeless Brotherhoods of Xtianity, that the conical hat remained in use. The Spaniards are the main ones that held fast to this piece of attire. Intolerance and its representation of “wrongness” continued for the hat. It began being used for those serving “penance” with the Church.

The Practitioners who walked this Path were called Penitents. Traditionally in Spain, those wearing the conical hat were known as capirotes. It was used during the times of the Spanish Inquisition as a punishment. Bastardized as many things were from the histories of previous peoples, the condemned by that Tribunal were obliged to wear a yellow robe – saco bendito, also known as a blessed robe that covered their chest and back. along with the hat. The hat was a paper-made cone on their heads with different signs on it, alluding to the type of crime they had committed. For instance, those to be executed wore red. The were also green, white and black colors worn.

The Church’s power began to waiver again and they had to do “something” to bring it back to their grasp. One of their thinkers, whom I believe was connected to the Inquisition, began looking around for ways to do this. In 1214, The Dominican Order was established in the Catholic church. The first group on their radar was the Manicheans. For more than a thousand years, since the Roman Empire was in power, war with the Persian Empire (Middle East) which included the Manichaeans, carried on. The Manichaens were seen as representatives of a foreign power and as dangerous aliens, even though they were but a small section of Persia. Sound familiar?

The Mani had not been supporters of the Persian Empire's wars with other lands, including Rome, but that was overlooked. The Romans persecuted the Manichaeans, while Jews were also being persecuted. And without the backing of the brute power of a major state in the Middle East/Persia, Manichaeism would all but disappear in the future. They were considered “outcasts” in their own society. I wonder if they wore “conical hats”? Do you know who the Yazidi are? You should.

While this was happening, we move further into the 12th century with our hat. The Mongol Queens from the Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, were wearing these conical hats too. Originating from the Mongol heartland in the Steppe of central Asia. By the late 13th century it spanned from the Pacific Ocean in the east to the Danube River and the shores of the Persian Gulf in the west. Khan’s was a competing empire for world dominance. None the less, there were no real differences in men and women’s clothing for the time but the Mongols needed to be seen from great distances, hence, the tall conical hat. This empire would not last against another… and the hat traveled.

As the story goes, Marco Polo brought back a sample of this hat to Europe in the 14th Century. The voracity of land grabs had already begun in the World. Mother Nature was being raped and disregarded and “fashion” became more important than meaning or purpose. The women of the time began wearing a conical hat called a hennin, not as Practitioners, but as fashionistas of their time. Very much unlike the willow-withe and felt Boqta (Ku-Ku) of Mongolian Queens. This appropriation became known as “the princess hat” and was worn tilted back on the head and veiled with brightly colored fabrics.

The “witch”, a word now derived from the Old English nouns wicca with an Old English pronunciation: [ˈwɪttʃɑ], meaning 'sorcerer, male witch, warlock' and wicce, the Old English pronunciation: [ˈwɪttʃe] for 'sorceress, female witch', actually becomes murky in meaning and language after this. The “witch” hunts were now well under way.

Since the beginning of its blighted past, the conical hat has stood to represent those outcast by their society. This seemed more prevalent in the later half its history. Why? The perpetuation of it being “negative” began with the Church.

It is of my opinion, the wearers of this hat were hold outs of Old Religion, Earth-Minded Folk and others at the turn of “the Christ event”. Because they did not or would not subscribe to what they were being sold, they became outcast from the forward momentum of society at that time. “Those in power”, i.e. Rome and later Europe and North America would not stand for anyone that did not conform to their forward march of greed and exploitation of Earth and “lesser humans”.

As we slipped into the 15th century, thousands were dying at the hands of those in power. The danger of witches became a widespread public concern. Urbanization and increased trade with foreign lands, along with epidemics of plague and cholera resulting from that trade, the onset of the Little Ice Age, upset feudal and religious hierarchies, ALL gave way to a convoluted mindset. “Something” had to be the cause. The was NO personal accountability. There was a widespread sense that the uncontrollable forces of change were destroying all order and moral tradition and the Church’s control. Persecuting witches redefined society’s moral boundaries and secured who was in control. This shift lent a leg up to allowing, and almost requiring, the demoralization of self if one did not conform or think or act like the majority in society. Differences in people, like those who were LGBTQ, although a part of us for thousands of years, were persecuted by the Church.

While we are passing through the 15th century, let us also consider the possibility that the witch’s hat is an exaggeration of the tall, conical “dunce’s hat” that was popular in the royal courts of the time as well. Or, let us consider the tall but blunt-topped hats worn by Puritans and the Welsh, who also had separate ideas than the majority. No matter what the fashion, pointed hats were frowned upon by the Church, which now associated points with the horns of the devil to maintain its power and fear-mongered agendas.

Let us also consider, somewhere along the way, an artist took creative license and added a brim to the timeless conical hat. Why would they do this?

Brimless, conical hats had long been associated with male wizards, magicians, Jews, Mani and many other societal outcasts. And, it was a male dominated society as the shift was happening. Goya even painted witches with such hats. It is possible that an artist added a brim to make the hats more appropriate for women (according to the fashion “rules” at the time) and to better fit this agenda of forward motion and subservience of others. One theory holds that the stereotypical witch’s hat came into being in Victorian times or around the turn of the century, in illustrations of childrens’ fairy tales. The tall, black, conical hat and the ugly crone became readily identifiable symbols of wickedness, to be feared by children. Hence, more fear-mongering was created in the name of control by the Church.

I do not feel I need to retell the rest of the history of the conical, now brimmed, black hat of the last 500 years. You should all be aware of the many “witch” trials by now. You have walked through history with me. You see where it comes from. You see why Georgia Black Hat Society has the Mission Statement it does. You see, my fellow Practitioner, why I take the stances that I do and want to hold to a belief of ONENESS of all things, just as my kindred folk of the previous thousands of years have done. Not war. Not greed. Not conquering my neighbors’ houses while wearing the now hijacked “black hat” of the social elite.

Harmony. Love. Unity.

THAT is what this all means to me.

More to come.

Blessings.

Reverend Richoz, RN

#georgia black hat society#national black hat society#conical hat history#black hat history#practitioner#witch

0 notes

Text

For those in Dire need of a Historygasm: The **Full** bibliography for my posts about Boqtas and Hennins

The Karakalpak Sa'wakele (contains further sources)

Theorizing Cross-Cultural Interaction among the Ancient and Early Medieval Mediterranean, Near East and Asia (edited by Matthew P. Canepa)

Women's Hats, Headdresses, and Hairstyles: With 453 Illustrations, Medieval To Modern, Georgine de Courtais (hennins) (turbans)

Medieval Clothing and Costume: Displaying Wealth and Class in Medieval Times, Margaret Scott (tartar/tatar cloth)

Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A cultural history of Islamic textiles

A Trader in Tatar Cloth (1350s)

Mongol Elements in Western Medieval Art (wikipedia-soft source)

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued his Empire, Jack Weatherford

Martial recap of Mongol forces in Europe

Legacy of Mongol Occupation (soft source)

Map of Mongol Occupation/Movements

Omayyad Clothing: In Persia from the Arab Conquest to the Mongol Invasion

ADDITION by asianhistory:

There’s actually records of this in fashion/costume history:

Although Flanders has the reputation of their [hennin’s] introduction, I much suspect their origin to have been Oriental and of great antiquity.

— A Cyclopedia of Costume vol. II a General History of Costume in Europe. pg. 128, c. 1879.

THE REST IS UNDER THE CUT

Extended Bibliography via Karakalpak.com

Abbott, J., Narrative of a Journey from Herat to Khiva, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg, Wm. H. Allen and Co., London, 1843.

Allamuratov, A., Everlasting Heritage [in Karakalpak], Bilim Publishers, No'kis, 1993.

Allsen, T. T., Commodity and exchange in the Mongol empire, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997.

Andrianov, B. V., and Melkov, A. S., Forms of Karakalpak National Ornament [in Russian], Archaeological and Ethnographical Works of the Khorezm Expedition, Volume 3, Materials and Research on Karakalpak Ethnography, page 411 onwards, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1958.

Anon., The Kirghiz-Kazakhs, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, pages 791 to 803, William Blackwood, Edinburgh, January to June, 1841.

Antipina, K. I., Special Material Culture and Applied Arts of the Southern Kyrgyz [in Russian], Chapter 3 Costume and Adornments, Published by the Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR, Frunze, 1962.

Arkell, A. J., Cambay and the Bead Trade, Antiquity, Volume 10, Number 39, pages 292 to 305, 1936.

Asanova, S. Zh., Saukele, Studies in the History of People's Costume [in Russian], Fashion Academy Symbat, Almaty, 2004.

Azarpay, G., Sogdian Painting, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1981.

Bardanes, C., Tagebuch über seine Reisen in der Kirgisischen Steppe mit des Herrn Professor Falks [in German], addendum to Beyträge zur topographischen Kenntniss des Russischen Reichs, Volume 1, by Johann Peter Falk, Kaiserl. Academie der Wissenschaften, Saint Petersburg, 1785.

Battutah, ibn, The Travels of ibn Battutah, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1958-2000.

Benin, V. L., Description of the Culture of the Peoples of Bashkortostan, Kitap, Ufa, 1994.

Boyer, M., Mongol Jewellery, Thames and Hudson, London, 1995.

Ch'ang Ch'un, K., Si Yu Ki: Travels to the West of K'iu Ch'ang Ch'un, Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources, Volume 1, translated by E. Bretschneider, pages 35 to 108, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London, 1887.

Clavijo, R. G. de, Embassy to Tamerlane 1403-1406, translated from the Spanish by Guy Le Strange, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., London, 1928.

Davis-Kimball, J., Chieftain or Warrior-Princess? Archaeology, Volume 50, Number 5, September/October 1997.

Davis-Kimball, J., Warrior Women, Warner Books, New York, 2002.

Davis-Kimball, J., Statuses of Eastern Early Iron Age Nomads, Papers from the EAA Third Annual Meeting at Ravenna 1997, Volume 1, Pre- and Proto-History, pages 142 to 149, Archaeopress, Oxford, 1998.

Davis-Kimball, J., Eurasian Warrior Women and Priestesses. Petroglyphic, Funerary, and Textual Evidence for Women of High Status, Center for the Study of Eurasian Nomads, Ventura, CA, 2005.

Dawson, C., The Mongol Mission, Sheed and Ward, London, 1955.

de Levchine, A., Description des Hordes et des Steppes des Kirghiz-Kazakhs, translated from the 1832 Saint Petersburg publication by Ferry de Pigny, L'Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1840.

Esbergenov, X., Private discussions at the Department of Ethnography, Karakalpak Branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, Amir Timur ulitsa, No'kis, June 2005.

Esbergenov, X., The Sa'wkele (on the Origin or Ethnogeny of the Karakalpaks) [in Russian], Ethnic World, Number 4, Information and Research Centre of the Kyrgyzstan People's Assembly, Bishkek, 1999.

Falk, J. P., Beyträge zur topographischen Kenntniss des Russischen Reichs [in German], Kaiserl. Akademie der Wissenschaften, Saint Petersburg, 1785.

Galiullina, G. R., Saukele. Helmet-shaped bridal Wedding Attire [in Russian], Bulletin, Issue 1, pages 88 to 93, Karakalpak Branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, No'kis, 1974.

Georgi, J. G., A Description of All the Nationalities that Inhabit the Russian State [in Russian], Volume 2, Saint Petersburg, 1776 to 1777.

Gladyshev, D. V., and Muravin, I., Journey from Orsk to Khiva and back, completed in 1740-1741 by Lieutenant Gladyshev and Geodesist Muravin, Geographical Proceedings, Published by the Russian Geographic Society, Issue 4, Saint Petersburg, 1850; Second Publication, 1851.

Gmelin, J. G., Voyage au Kamtschatka par la Sibérie, Tom 2, Histoire Général des Voyages, E. van Harrevelt & D. J. Changuion, Amsterdam, 1780.

Ivanov, V. A., and Kriger, V. A., Kurgans of the Kipchak Era on the Southern Urals (12th - 14th centuries) [in Russian], Nauka, Moscow, 1988.

Ja'nibekov, O'., Qazaq Costume, Album, O'ner, Almaty, 1996.

Jenkinson, A. and other Englishmen, Early Voyages and Travels to Russia and Persia, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1886.

Kies, M. L. and la Rus, S., Women's Clothing in Kievan Rus, Medieval Textiles, Complex Weavers Study Group, Issue 27, pages 4 to 22, , Lemont, Illinois, March 2001.

Klima, L., The linguistic affinity of the Volgaic Finno-Ugrians and their ethnogenesis, Department of Finno-Ugric Studies, ELTE University, Budapest, 2004.

Klimovich, L., The Karakalpak People's Poem "Forty Girls" [in Russian], pages 5 to 19, No'kis, Karakalpakstan, 1983.

Kun, A. L., compiler, Turkestanskiy Albom [in Russian], according to the order of the Turkestan Governor-General, Adjutant-General K. P. von Kaufmann, Ethnographical Section, Native Peoples of the Russian Possessions of Central Asia, 1871 - 1872.

Lansdell, H., Russian Central Asia, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1885.

Lobacheva, N. P., The History of Central Asian Costume: The Karakalpak Kimeshek [in Russian], Results of Field Research, Volume 5, edited by G. A. Nosova, pages 54 to 73, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology RAN, Moscow, 2000.

Lobacheva, N. P., Central Asian Costume of the early Medieval Epoch (according to information from wall paintings) [in Russian], Costumes of the Peoples of Central Asia, edited by O. A. Sukhareva, Science, Moscow, 1979.

Mallory, J. P., and Mair, V. H., The Tarim Mummies, Thames and Hudson, London, 2000,

Morozova, A. S., The Domestic Cultural Life of the Karakalpaks [in Russian], Doctoral Thesis, Department of History, Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1954.

Morozova, A. S., Karakalpak Female Helmet-shaped Headdress "Saukele" [in Russian], Soviet Ethnography, Volume X, pages 134 to 139, 1963.

Moser, H., A travers l'Asie Centrale, E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie., Paris, 1885.

Muravyev, N., Journey to Khiva through the Turkoman Country, Oguz Press, London, 1977.

Onon, U., The Secret History of the Mongols, The Life and Times of Chinggis Khan, RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2001.

Pallas, P. S., Kupfer zu P. S. Pallas Neuen Reisen in die südlichen Statthalterschaften des Russischen Reich in den Jahren 1793 und 1794, Volume 1, Martini, Leipzig, 1799.

Pauli, G. F. C., Description Ethnographique des Peuples de la Russie, Tom 1, Imprimerie de F. Bellizard, Saint Petersburg, 1862.

Pletneva, S. A., Polovtsy [in Russian], Nauka, Moscow, 1990.

Polosmak, N. V., The First Report on a Burial of a Noble Pazyryk Woman on the Ukok Plateau, Altaica, Number 4, page 9, Novosibirsk, 1994.

Polosmak, N. V. and Molodin, V. I., Grave Sites of the Pazyryk Culture on the Ukok Plateau, Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, Volume 4, Novosibirsk, 2000.

Rakhimova, Z. I., Central Asian women's costume in the 16th-17th century miniatures of Maverannar, Culture of the Middle East [in Russian], pages 135 to 151, FAN, Tashkent, 1990.

Rashid al-Din, The Successors of Genghis Khan, translated by J A Boyle, Columbia University Press, New York, 1971.

Reeder, E. D., Scythian Gold, Harry N. Abrahams, Inc., New York, 1999.

Rolle, R., The World of the Scythians, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1980.

Rossikova, A. E., On the Amu Darya from Petro-Aleksandrov to Nukus [in Russian], Russian Bulletin, Number 8, pages 562 to 588, Saint Petersburg, 1902.

Rudenko, S. I., Frozen Tombs of Siberia, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London, 1970.

Rusyaykina, S. P., Museum Ethnographic Funds as a Source for the Composition of the Historical-Ethnographic Atlas of Central Asia and Kazakhstan [in Russian], pages 36 to 85, Materials on the Historical-Ethnographical Atlas of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, edited by T. A. Zhdanko, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow-Leningrad, 1961.

Sazonova, M. V., Morozova, A. S., and Leykina, S. M., Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan in the Collections of the State Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR [in Russian], Materials on the Historical-Ethnographic Atlas of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, edited by Zhdanko, Moscow-Leningrad, 1961.

Sazonova, M. V., Women's Costume of the Uzbeks of Khorezm, Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Publishers Nauka, Moscow, 1989.

Schuyler, E., Turkestan, Notes on a Journey in Russian Turkestan, Khokand, Bukhara and Kuldja, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, 1876.

Shalekenov, U. Kh., Kazakhs of the Lower Amu Darya [in Russian], Fan Publishing, Tashkent, 1966.

Smirnov, K. F. and Rudenko, S. I., Scythian finds from the Altai Mountains, History Issues, Number 2, 1953.

Sobolyev, L., Letters about the Amu Darya Expedition, Russian Invalid, Number 216, Saint Petersburg, 1874.

Spencer, E., Travels in Circassia, Krim-Tartary, Etc., Volume 2, Published by Henry Colburn, London, 1839.

Sukhareva, O. A., Bukhara, 19th to the Early 20th Century [in Russian], Nauka, Moscow, 1966.

Tolstov, S. P., The Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition, Academy of Science of the USSR (1945-1948), Archaeological and Ethnographical Works of the Khorezm Expedition, 1945-1948, Volume 1, pages 7 to 46, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1952.

Vambery, A., Travels in Central Asia, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1970.

Vambery, A., Sketches of Central Asia, Wm. H. Allen & Co., London, 1868.

Weber, F. C., The Present State of Russia, Volume II, Section VI, M. Le Brun's Observations on his Journey through Russia to Persia, W. Taylor, London, 1722.

Yatsenko, S. A., The Costume of Foreign Embassies and Inhabitants of Samarkand on Wall Painting of the 7th Century in the "Hall of Ambassadors" from Afrasiab as a Historical Source, Transoxiana, Volume 8, University of Salvador, June 2004.

Yatsenko, S. A., Late Sogdian Costume (5th to 8th century AD), Webfestschrift Marshak Ērān und Anērān, Studies presented to Boris Illich Marshak on the occasion of his 70th birthday, edited by M. Compareti et al, 2003.

Zakharov, I. V., and Khodzhayeva, R. D., Kazakh Head Wear, Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, pages 216 to 227, Nauka, Moscow, 1989.

Zhdanko, T. A., Material on the Applied Arts of the Karakalpak People [in Russian], Archaeological and Ethnographical Works of the Khorezm Expedition, 1945-1948, Volume 1, pages 559 to 567, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1952.

Zhdanko, T. A., The Ornamental Folk Art of the Karakalpak People [in Russian], Archaeological and Ethnographical Works of the Khorezm Expedition, Volume 3, Materials and Research on Karakalpak Ethnography, pages 373 to 410, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1958.

Zhdanko, T. A., Work of the Karakalpak Ethnographical Force in 1956, Field Studies of the Khorezm Expedition in 1954 – 1956 [in Russian], Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1959.

Zhdanko, T. A., and Esbergenov, Q, Ethnography of the Karakalpaks [in Russian], Fan Publishing, No'kis, 1980.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mongolian Women Series by Artist Su Ruya.

Mongolian Noble Women. Su Ruya. Painting, 2017 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 9, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2002 [image source].

Mongolian Women No. 2, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting [image source].

Mongolian Women No. 1, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 1998. [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 10, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2002 [image source].

Golden Age. Su Ruya. Painting, 2014 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 15, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2015 [image source].

Mongolian Woman No. 5, Mongolia Imagery Series. Su Ruya. Painting, 2000 [image source].

#mongolia#inner mongolia#chinese art#china#chinese artists#inner mongolian artists#asian art#mongolian fashion#traditional mongolian fashion#su ruya#su ruya artist#painting#art#boqta#gugu hat

35 notes

·

View notes