#both very real 17th century guys whose names I encountered at work

Text

in times of trouble, I cling to the fact that my name is neither Dirck Gryp nor Terence Eunuchus

#both very real 17th century guys whose names I encountered at work#will update if I come across more

0 notes

Text

McMansion Hell Does Architectural Theory (Part 3): British Palladianism

Hello Friends! Today we’re going to talk about a rather short-lived movement in late 17th, early-18th century architecture: British Palladianism, which is v “Palladio is great and I, an aristocrat, will only pay you if you design in reference to his style.” Of course it goes deeper than that, so, let’s begin!

Background

In previous installations of this series, we’ve talked about the Italians and the French, but what the heck was happening in Britain all this time? Well, the answer is:

Seriously. The dang Brits were at war all the time - colonializing everything, sinking all of Spain’s ships, creating their own cool church bc their king wanted a son etc.

Because of all this dang war, architecture in Britain for a long time was a messy hodgepodge of stylistic elements. Examples range from Henry VIII’s Windsor Castle Gatehouse (OG Tudor, though ostensibly Gothic) to the more classically-oriented but still rather Gothic Old Somerset House (completed in 1552) (demolished). According to Mallgrave’s Architectural Theory (a great anthology), most of the classically inspired elements on pre-17th Century British buildings can be traced to Italian or French artisans. Oh well.

Early English Classicism (Late 17th Century)

It wasn’t until the 17th century (v late) that classicism became a big deal in England. The first real-deal English classicist was the badass-ly named Inigo Jones, who actually went to Italy for a year (1613-14) where he encountered the work of Palladio for the first time -- which, needless to say blew his damn mind. Jones became the first British architect to have designed buildings in accordance to Vitruvian teachings and classical proportions.

The Dude Jones got into architecture through a weird angle: he was first a prominent set and costume designer for several English theatres. His Italian journey proved fruitful for him career-wise - many of the higher-ups were impressed with Jones’ knowledge of Italian aesthetics, and he was shortly appointed as the Surveyor to the Prince of Wales, before hella upgrading to being Surveyor of the King’s Works in 1615.

Jones’ earliest known architectural work (appropriately called Queen’s House), built for James I’s wife, Anne (who died before it was finished), was the first ever classically styled building in England. I mean, it’s great - just look at it.

Photo by Bill Bertram (CC-BY-SA 2.5)

While Jones would go on to design a smattering of buildings, a great deal of his work was lost both in the English Civil War and in the 1666 Great Fire of London. Despite these minor setbacks, Jones’ is still considered to be among England’s greatest architects whose influence would span two centuries worth of British architectural technique.

Get it? It’s lit? Because half of his stuff got torched? I’m sorry.

As far as architectural theory goes during this era of budding classicism, the closest clue we have is the work of Henry Wotton, the British ambassador to Venice, who got so hellaciously sloshed on Italian architecture while he was there that he decided to write a book about it called The Elements of Architecture (1624), outlining his special interpretation of classical architecture.

Wotton’s book was mostly a translation of Vitruvius with a little bit of Renaissance thought (a la Alberti and Palladio) thrown in. The most well-known snippet is his translation of the Vitruvian triad as “firmness, commodity, and delight” - an architectural catchphrase that often finds its way into contemporary architectural histories, though more accurate translations have been proposed:

Change in this line of thought came with Jones’ later successor, Christopher Wren. Unlike Jones who was rather rigorous in his classicism, Wren was a bit more...capricious. In fact, he even built in the Gothic style at the end of his long career (the dude built 45 churches alone) - a move that would have likely put Perrault and Blondel both in an early grave.

Dude doesn’t even need the sunglasses, he’s throwing so much shade in this pic.

Wren’s ideas about architecture, encapsulated in his Tracts on Architecture (1670s) are varied. In Tract I, Wren opens up with the ballsy af statement: “Architecture has its political Use,” - that is, buildings form the national identity of a country and inspire patriotism amongst its citizens. This itself is a hot take, but it gets even hotter.

Like Perrault, Wren’s ideas about beauty are split into what he calls “natural” and “customary” beauty. Natural beauty consists of geometry, aka Proportions, following in the Platonic tradition® of an absolute beauty or harmony, inherently pleasing to all of us. Customary beauty, however, is more vague - Wren describes it as: “the use of our Senses to those Objects which are usually pleasing to us for other Causes, as Familiarity or particular Inclination breeds a Love to Things not in themselves lovely.”

Basically, we like certain things for some dumb reason like feelings and stuff.

In his second Tract, Wren gripes about architecture being “too strick and pedantick.” This makes sense, because Wren was really into blending a variety of interesting styles together, which was perhaps problematic to some.

Enter the Moralists

One person who was particularly sick of Wren’s sh*t was Anthony Ashley Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury, who, in addition to being an Earl, was also a writer and philosopher. (He was notably taught at a young age by none other than John Locke, the guy you learned about in Civics class once.)

Shaftesbury hated (!!!) the Baroque stylings of Wren’s late work, as well as the next generation of architects including John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor, deeming the pair’s Baroque-leaning Blenheim Palace “a new palace spoilt.” In fact, he wrote a very amusingly scathing essay in 1712 basically saying that Britain was literally *THE BEST* at all of the other arts except for architecture, after which he proceeds to take a huge dump all over the architecture of the day.

Photo by Derova, (CC-BY-2.0)

Shaftesbury tried to sniff out a philosophical basis for Platonic thought regarding absolute beauty and harmonic proportions. What he came up with is essentially moralism, claiming that in order to be able to perceive the naturally good and beautiful ideas in art, one must themselves be naturally good and beautiful on the inside.™ Good taste comes from good inner resolve® to be true to what we know is true beauty and not be swayed by the evils of fashion™ blah blah blah.

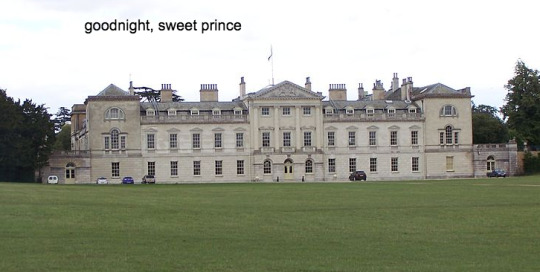

The Height of British Palladianism

This line of thought continued within what was now deemed British Palladianism (a movement whose discourse consisted mostly of wealthy Earls tutting at each other). British Palladianism saw several architects (Colin Campbell, Nicholas Du Bois, and William Kent, specifically) launch their own careers by releasing translations or new editions of works by Vitruvius, Palladio, and Jones, respectively with some pithy bits in the introductions haranguing the “ridiculous mixture of Gothick and Roman” of the previous generation thrown in for good measure.

Like all movements, the Palladian movement had its own shadowy figurehead, who funded the work of several of the architects working in the 1720s - Richard Boyle, Third Earl of Burlington.

Burlington was extremely wealthy, and spent most of his time being a total dilettante architect, traveling to Italy to collect manuscripts of Palladio and the like. In fact, Burlington fired Colin Campbell (the English Vitruvius!!) from working on his Piccadilly Villa because apparently Campbell’s classicism was **just not pure enough** for the good Earl, who decided he should just build his damn villa himself.

Burlington’s ruthless aesthetic commitment had a huge impact on the contemporary architects of the day, most of whom he fired. Of the ones he did not fire (aka he did not hire them in the first place), Robert Morris, the most prolific writer of the Palladian movement, is perhaps the most significant. Morris’s work chronicles not only the dawn and spirit of the movement but also its decline.

Morris’s 1728 essay “An Essay in Defense of Ancient Architecture” is about exactly what you would expect:

(((Tutting intensifies)))

The essay of course devolves from tutting critique to legit 17th century fanfiction:

I-Inigo-sama!!! <3

The End of an Era, I Guess

Jokes aside (yours truly used to ship historical figures back in my 7th grade fanfiction days and is not proud), Morris would take a rather different tone in 1739, in an essay commonly cited as a hint to the movement’s end, “An Essay upon Harmony.”

This essay breaks away from the Platonic ideas of absolute beauty, and instead breaks beauty up into several different categories - a relativist aesthetics coming from a contemporary movement (mostly in landscape architecture) called the picturesque, or picturesque theory, which will be the subject of next week’s post.

“In Harmony,” writes Morris, “there are three general Divisions, which may be distinguish’d by the Terms, Ideal, Oral, and Ocular.”

The Ideal is of course numbers and, duh, proportions. Oral harmony is how things are related to each other, with a v Plato allusion to musical harmony. Old news, right?

But it’s Ocular harmony that offers a glimpse into what will ultimately be a much more powerful movement, spanning (serious, not dilettante) philosophy, art, and of course architecture: the picturesque and the sublime, supported by John Locke & Co.’s empiricism (but we’ll get to that).

Ocular harmony is the harmony of nature in its natural state - both “Animate” (animals, insects, also beauty and perfection, apparently) and “inanimate” (hills, woods, valleys, scenery - “noble, rural, and pleasing.”)

Morris’ ideas are ones of subjectivity, blind sensation to what is and is not lovely, rather than dictated ideas of aesthetic morality. He later goes on to say that in architecture, “The Proportion should be with respect to the Situation; the Dress, Decoration, and Materials should be adapted to the Propriety and Elegance of the Situation and Convenience…”

If that’s not the antithesis to Burlington’s objective classicist purity, I don’t know what is. And so, the bell finally tolls on British Palladianism.

Photo by Chris Nyborg, (CC-BY-SA 3.0)

I hope you enjoyed this bit of (admittedly long-overdue) tutting. Stay tuned for Wednesday’s Maine McMansion, and next Sunday’s installment where I trash talk a bunch of dudes who are way too into gardens.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon! Not into small donations and sick bonus content? Check out the McMansion Hell Store - 30% goes to charity.

Copyright Disclaimer: All photos without captioned credit are from the Public Domain. Manipulated photos are considered derivative work and are Copyright © 2017 McMansion Hell. Please email [email protected] before using these images on another site. (am v chill about this)

#architecture#history#architectural theory#palladio#philosophy#aesthetics#inigo jones#christopher wren#robert morris#england#british palladianism#classical architecture#classicism#traditional architecture#theory

446 notes

·

View notes