#but movies resonate harder than statistics

Text

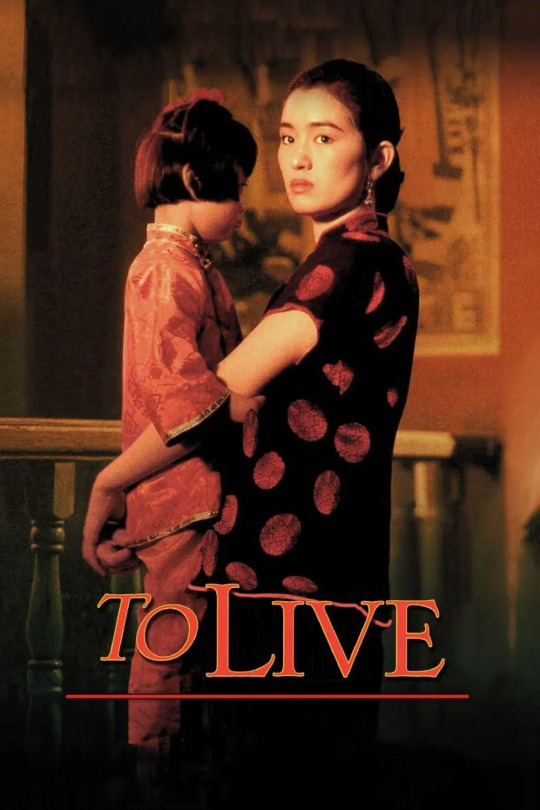

I have literally never seen any discussion of this film outside of the class I watched it in why is that this was such a horrifying film please we need to talk about it

#history#film#historical film#chinese history#mao zedong#china#maoist china#the cultural revolution#to live#chinese film#please#i need people to talk with me about this film#or people to talk about it online idk#i feel like a lot of people became maoists without knowing what things were like during the cultural revolution and the five year plan#and ofc one movie isn't enough to base a historical analysis on#but movies resonate harder than statistics#and idk it really got me to be anti-mao on top of all the statistics#while also showing that life could be normal at times#and shifting me to be pro-communal living 💀

1 note

·

View note

Note

What's the reason behind Haikyuu anime having more female fans despite having all-male cast ?

idk…? I never understood that whole "it has this and that so only those people have to/should like it more“ thing anyways. Videogames were fun, magical girl anime were fun, people can like both, what‘s the big deal? Child me didn‘t get it and adult me is very happy to report it stayed that way.

…I suppose a reason could be that it had a super popular ship, and shipping tends to be more done by women in fandom spaces statistically (idk why and it‘s important rn) though idk if it‘s popular ship -> female fans or female fans -> popular ship.

Or maybe it‘s because there‘s an all male cast? Like how anime with lots of women in them tend to just be bait for the cliché "needs to touch grass has never talked to women irl“ type people? All male casts could attract (non-lesbian) women?

It could also be that the main character‘s conflict comes from him having a physical disadvantage in his field compared to his pears because of genetics (he‘s short lmao) and having to compensate for it in a different way, as well as having a harder time initially getting taken seriously regardless of actual skill because others assume things based on it, which might resonate with female fans for hopefully very obvious reasons. (*points at all of society*).

OR, it‘s not even that Haikyuu has something specific drawing in women, but that other anime/anime fandoms are very unwelcoming to them. Anime is a lot like videogames, movies, etc in that regard - people just being hella creepy and misogynistic in certain spaces. Like with videogames; shooters are fun! But try touching a multiplayer shooter with a high voice and you will get shat on constantly from all sides, and despite what they say, it absolutely hits women (and people who sound like one in vc) more than guys.

Not to mention "oh you‘re a fan of…? Name every thing of it!“ is a meme because it‘s stupid but really a thing. That way more often tends to happen to women in fandom spaces. Also, just, anime having a lot of those "never touched grass“ types of people.

So the Haikyuu fandom evidently not having that type of issue as far as I’m aware (I did have a female friend who was into anime including Haikyuu lmao), could lead to female fans gravitating towards it, as they‘re not getting shat on for liking something for once.

Be it this or an other reason women initially started gravitating towards it, in any case i’d mean there‘s, well, more women liking Haikyuu, meaning they‘re more likely to share it with their friends who are also women, as well as strangers seeing "hey this is liked by lots of people like me, maybe I‘ll like this too!“, thus basically creating a confirmation loop. Women get into it, there‘s more women there, more women see it, women get into it, repeat.

#another anon ask#uhhh thank you for coming to my ted talk#…i have never seen a ted talk#they‘re not a thing here lmao#long post#…really need to learn how to *not* write essays all the time lmao

0 notes

Link

Thanks goes out to @yourownpetardfor bringing this to my attention with his post HERE.

Fifteen years ago, Hollywood’s glittering superstars—among them Meryl Streep— were on their feet cheering for Roman Polanski, the convicted child rapist and fugitive from justice, when he won the 2003 Academy Award for Best Director. But famous sex criminals of the motion picture and television arts have lately fallen out of fashion, as the industry attempts not just to police itself but—where would we be without them?—to instruct all of us on how to lead our lives.

The Golden Globes ceremony had the angry, unofficial theme of “Time’s Up,” which quickly and predictably became unmoored from its original meaning, as excited winners tried to align their entertaining movies and TV shows with the message. By the time Laura Dern—a quiver in her voice—connected the nighttime soap opera Big Little Lies to America’s need to institute “restorative justice,” it seemed we’d set a course for the moon but ended up on Jupiter: close, but still 300 million miles away. And then Oprah Winfrey climbed the stairs to the stage, and I knew she wouldn’t just bat clean-up; she’d bring home the pennant.

Winfrey began speaking to crowds at the age of 3. “Little Miss Winfrey is here to do the recitation,” the preacher would say, and the whole congregation would lean in to listen to the remarkable child. As far as sexual abuse is involved, no one speaks with greater personal authority; the first time she was raped, she was 9. “I knew it was bad,” she said later, “because it hurt so badly.” From the second she started speaking at the Golden Globes, filling the ballroom at the Beverly Hilton with her rich, confident, and sui generis voice, she gave the night what it had so desperately wanted: emotional coherence.

She smoothly accomplished what other speakers had struggled to do: She connected the grotesque but statistically insignificant problem of sexual harassment in Hollywood to the larger fate of women and girls. “It’s not just a story affecting the entertainment industry,” she said; “it’s one that transcends any culture, geography, race, religion, politics, or workplace.” She said that a new day was on the horizon—this was near the end of the speech, by which point she could have marched the crowd right over to The Weinstein Company and torched the place—and that the catalyst for this important change was the number of women willing to “speak their truth.” In that moment, all us watching from home witnessed the revolution become a movement.

Less than a week later, the movement became a racket. A previously obscure website called Babe, which is operated by a group of very young women in Brooklyn, got a hot tip. Through the grapevine, the staff had heard that another young Brooklyn woman had been talking about being sexually violated by the comic Aziz Ansari. They reached out to a woman they called “Grace,” persuaded her to “speak her truth,” albeit anonymously, and rushed the piece into publication: Ansari was given less than six hours to respond to these reputation-destroying allegations. There was no need for the furious pace—this wasn’t a breaking story about a political election or a natural disaster—which seemed to have been motivated by the urgency of the “Time’s Up” motto. Almost immediately the piece became the object of intense cultural interest, with many commentators (including myself) deciding that Ansari had been unfairly treated by the website. Just as many others, particularly young women, said that the account resonated deeply with them, and concluded that Ansari had violated Grace.

Predictably, the piece drove huge traffic to Babe, and visitors who explored the site were exposed to its credo: Babe is created by and for “girls who don’t give a fuck.” Collectively, the articles address what the site suggests are universal conditions of the young female heart, or at least conditions universal to its fans. Unfortunately, many of these shared concerns boil down to an almost exact list of traits which blatantly misogynist websites like Return of Kings have enumerated for years.

The Babe girl is

MANIPULATIVE (“Period-Trapping Is the Only Way to Find Out if You’re in a Relationship or Not”)

INSECURE (“You Should Be Secretly Looking Through Your Partner’s Phone”)

ADDICTED TO DRAMA (“We Pranked Our Exes and Asked Them to Be Our New Year’s Kiss and It Was a Complete Disaster”)

JEALOUS (“You’re Not Paranoid: This Is How to Tell If Someone Else Is Closing In on Your Man”)

OBSESSED WITH TEARING DOWN THE SAME FEMALE SHE’S IDOLIZES & ENVIES (“Amber Rose’s Plastic Surgery Is Absolutely a Feminist Statement” and “Sorry, but Kendall Jenner Can’t Model for Shit”).

The Ansari piece was written by a recent college graduate named Katie Way, who shot into the popular awareness like a rocket blasting away from Cape Canaveral on Sunday night, only to plummet—flaming and disintegrating—by Wednesday. On Monday, she was excited to appear on CBS This Morning to discuss her piece, tweeting, “Catch me on @CBSThisMorning brrright and early tomorrow morning, can’t wait for America to hear my weird low voice.” But her anger toward those who would question her motives and moral rightness was soon piqued by the HLN news analysis show Crime & Justice. The host, Ashleigh Banfield, read an open letter to “Grace” in which she said, “You have chiseled away at a movement that I, along with all of my sisters in the workplace, have been dreaming of for decades.”

The producers reached out to Way, via a direct message on social media, inviting her to come on the show to discuss the essay. At this point, Way abandoned the low voice for the high-pitched screech of the angry teenager. She wrote back that she wouldn’t go on the program, principally because Banfield was too old and unattractive, called her a “burgundy lipstick, bad highlights, second-wave feminist has-been,” and said that “no woman my age would ever watch your network. I will remember this for the rest of my career—I’m 22 and so far, not too shabby!”

I happened to be sitting in a Los Angeles green room waiting to appear on Crime & Justice the night when Banfield read part of this fantastical letter on the air, at which point the entire Katie Way arc of the story seemed to have turned into an unfilmed episode of Girls: the time Hannah wrote a hit-piece on a famous celebrity but only did half the amount of work required, and when confronted about it by a respected journalist she fired off a nasty letter that might have seemed like a great idea in the moment but ended up getting read on national television. Suffice it to say, it seemed that Katie Way—beloved only child, recent graduate of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, nongiver of fucks—had bitten off more than she could chew.

Like many news and information websites created by young women, Babepublishes many stories on sexual assault. But unlike most other such outfits, it also runs stories about the pleasure of rape fantasies. Feminists have fought for years to keep the notion of rape fantasy as far as it could possibly get from actual reports of sexual assault. But those were feminists who gave a fuck. Babegleefully, witlessly runs angry pieces about sexual assault as part of the same cotton-candy pink, swirling galaxy as the ones that describe the pleasures of fantasizing about rape. The site has devoted many pixels to explaining to readers how enjoyable and common these fantasies are.

Babe explains to readers that rape fantasies serve lots of worthy sexual desires: “You want to know you’re wanted”

(“A Clinical Psychologist Revealed Why Women Have Rape Fantasies and It’s Totally Fascinating”)

“What I like about rape fantasies is the loss of control” (“These Women Revealed Why They’re Into Rape Fantasies”)

“It’s all about ‘sexual desirability’” (“There’s a Major Rape Fantasy Sub-Culture Out There That’s Pretty Intense”)

“I hear how rape fantasies can be exciting and fun, even for those who have been raped. It’s not an unhealthy expression of sexuality” (“A Sexologist Explains Why Women Have Rape Fantasies”)

“I beg him to stop while he carries on fucking me harder and harder. I dig my nails into his back with tears in my eyes and whisper that I want to go home” (“Sex IRL: The Grad Student With Graphic Rape Fantasies”).

Many of the pieces on actual sexual assault are filled with the precise, clinical detail that is the hallmark of reporting on the subject, such as the texts between two high school students after a drunken hook-up which the girl said constituted an assault, but which the boy thinks was not: “Wanna clarify that we didn’t fuck last night … I ate you out and fingered you, but that’s it.”

Obviously these two types of story are in conversation with one another. For girls who enjoy rape fantasies, the vividly reported sexual assault reports provide a world of concrete details to feed into them.

Katie Way’s college interests were journalism and creative writing. At Northwestern she wrote skillfully composed short stories in a vein of fiction she admired: magical realism. One of the reasons her Babe story has such an impact on readers—other than its naming of a very famous man—was its literary skill: It’s filled with precise details, and provides an immersive, world-building reading experience. On a “beautiful, warm September night” Ansari and Grace walked together to a romantic dinner spot, “Grand Banks, an Oyster bar onboard a historic wooden schooner on the Hudson River.” Over lobster rolls and a bottle of wine, they chatted about things that mattered to Grace: NYU, photography, and “a new, secret project” that Ansari was working on. They headed back to his apartment located in “an exclusive address on TriBeCa’s Franklin Street, where Taylor Swift has a place too.”

It was a night when a rich, successful, older man was taking a huge amount of interest in a young woman and treating her well: taking her to a fancy dinner, paying the check, listening to her stories. It’s a dream date. And then—as soon as they walk through the door of his apartment—the story turns dark and terrible. The language that Way uses to describe it is not the straight-ahead dispassionate language of crime reporting; it’s the language of pornography: “‘Where do you want me to fuck you? Do you want me to fuck you right here?’ He rammed his penis against her ass while he said it, pantomiming intercourse.”

The piece, with its dreamy opening, its pornographic passages, and its tone of aggrieved score-keeping over petty slights—HE DID OFFER HER THE KIND OF WINE SHE LIKES—has stirred something in young women.

But the piece is the almost inevitable consequence of a lifestyle promoted on the website, which enjoins young women to fulfill men’s sexual desires and to— literally—behave whorishly. Or, as a wrap-up of Babe’s 2017 service journalismput it: “You now know how to give life-changing blow-jobs, what it’s like to have rape fantasies, what percent hoe you are based on a scientifically accurate quiz, and how to keep your lipstick on even if your mouth is … otherwise occupied.”

Pulsing underneath all of this is the exact emotion which Katie Way lost control of Wednesday night: rage, so overpowering and so poorly understood that it can easily erupt and excoriate the wrong person.

In such swirls of high emotion and with diffuse goals, social entrepreneurship becomes lucrative. This Ansari episode, for example, has been a huge boon to the girls who don’t give a fuck, as they gleefully tell every reporter who asks them about it. As the writer Kerry Flynn wrote in an essay about the website published in Mashable, “For Babe, Grace's story was a big break—good for traffic and for the brand.”

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Step Back in Time with Ebbets Field Flannels’ Vintage Jerseys

More than any other major league sport, the history of baseball is intimately connected to graphic design. Think Yankee pinstripes, Dodger blue, and the Tigers’ Old English D. As a young boy growing up in 1960s Brooklyn, Jerry Cohen was well aware of that connection: While most of his friends were tearing open new packs of baseball cards in search of their favorite players, Cohen was focused on the uniforms, the logos, and the colors.

Fast forward to Seattle, 1987. Cohen is searching for an original wool baseball uniform to wear onstage while performing with his rock-and-roll band. When he finally realizes he’ll need to make it himself, he discovers a warehouse in Rockport, New York, with yards of baseball flannel dating back to the 1940s. Cohen made a few of his own jerseys, and before too long, people were asking to buy the shirts off his back. And Ebbets Field Flannels was born.

Three years later, Sports Illustrated highlighted the company, which quickly led to celebrity commissions from Spike Lee and David Letterman. Ebbets Field Flannels provided jerseys for 42 (the Jackie Robinson biopic), and outfitted Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, and other Hall of Famers at the closing ceremonies for Yankee Stadium in 2008. A die-hard Mets fan who now oversees 22 employees, Cohen recently added football and hockey jerseys to EFF’s collection, but vintage minor-league and Negro-League uniforms will always form the heart of the lineup, along with those from the historic international baseball hubs of Japan and Cuba.

When you decide to create a “new” product, where do you start?

I’m not like most clothing designers who think, “What will people like next season?” I follow history. It’s my job to be a curator and accurately take a two-dimensional form—often a black and white photo—and turn it into a three-dimensional form, which is a living, breathing piece of clothing. If I have any talent, that’s what it is.

I’m a little cagey on the subject of research; I don’t like to tell people about my methods because I have a lot of competition, and I’m not going to make it easy for anyone else. But I’ve collected a lot of reference materials over the years, and sometimes it’s very serendipitous—stuff comes across my desk and I follow leads, like any good detective.

What’s the most difficult thing about recreating these uniforms?

In many ways, it’s harder to do a simple thing than a complicated thing. Today’s graphic designers go their entire lives using Photoshop or Illustrator and many of them don’t understand the elegance and simplicity [of doing things by hand]. If you look at baseball graphics or athletic uniforms of today, the general approach is more—more colors, more layers, more of everything crammed into a very small space. But back in 1915 or 1945, it was the opposite; design literally meant someone drawing with a pencil in a sporting goods store, then someone else rendering that illustration into dies that were used to cut felt lettering.

Describe your typical customer.

When we started, there were still plenty of old timers who went to the games of the San Francisco Seals, let’s say, so that was our original market. Five or six years ago, we discovered a new market—much younger people who are driven by the craftsmanship of the products as much as they are by the history and the teams.

Now, our audience is much more diverse—we’re working with ACE Hotel and other contemporary brands [including Jack White’s Third Man Records], who seem to like our vintage approach. With so much cynicism in marketing—particularly in sports-related products—everything is so “of the moment,” but when the moment changes, all that stuff really seems obsolete. We try to sell timelessness.

Designers are always trying to connect people to brands, but it’s hard to think of a brand more powerful than baseball—simple letters and numbers and the words “New York” seem to add up to a lot more. True?

That’s where the history comes in—putting the letters and the colors in the context of history, finding those touchstones, and even bringing a story to people that they may not be aware of. If you could describe the Ebbets approach, it’s not, “Here’s a Yankees hat like they wore in the World Series,” because that’s been done. From the beginning, back in 1988, it was, “Do you know about the Negro Leagues? Did you know this whole other universe existed and it was wonderful and rich, full of all these amazing characters?”

As historians, we’re always trying to find those little stories, so that every product we make has some emotional connection or historical resonance. It’s not always possible to discover all the details about some of the more obscure teams, but I always try to find one or two things, even if it’s just a couple of interesting statistics from an old class B minor-league team from the ’30s. Because you have to give people something to sink their teeth into, beyond a black hat with a white “A” on it.

In one interview, you point out how much you love design from the ’30s to the ’60s, and although you’ve considered creating uniforms from the ’80s or ’90s, you’re not in any hurry. What was it about that earlier era?

I’m sure there are people who would respond to something from the ’80s or ’90s just as powerfully as I respond to something from the ’50s. But to me, the ’80s is when designs became dispensable and transient, with polyester materials and logos changing constantly, so I tend to lose interest.

Right around the ’70s is when you see regional domestic manufacturers get phased out of athletic garments, and big guys like Nike take over and it becomes more about marketing opportunities. Then the computer programs kicked in and everyone had to have their own Pantone color; it wasn’t just red anymore. We’ve recently started making more vintage collegiate uniforms and we have to explain to the schools that back in the day, there were really just seven or eight colors that everyone used; they didn’t make felt out of Harvard’s burgundy Pantone—those specs just didn’t exist. And there’s something I like about that.

It’s like playing music: Today you can have 64 digital tracks on top of one another, and the ability to make any sound you want, or you could hand someone an acoustic guitar and say, “You have to do it with this.” For me, it’s more interesting to work with a limited set of tools.

Today, no new professional sports team would choose to do something as simple as what the Yankees still wear: a one-color interlocking monogram. And yet, you can’t measure the value of that Yankees logo because it has 70 or 80 years of history behind it and it hasn’t really changed. I don’t mean to sound like everything was better “back in the day,” because that’s not true, but there’s something about American style from 1935-1972 that, for my taste, represents something really special.

You’ve been at this 30 years. Have there been any special moments when you were struck by the impact that your company has had?

The kind of people who buy our stuff are the kind of people I’d like to hang out with—experts in other fields. Early on, Spike Lee adopted us, before the Sports Illustrated article even came out—you’d open a magazine and see him wearing one of our Negro League jerseys. I remember opening up a copy of the Sunday New York Times, and seeing documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney in the section where they ask notable people what they’re watching and listening to, and under “What I’m Wearing” it says “Ebbets Fields Flannels”; I had no idea we’d be in the New York Times when I woke up that morning. I’m a huge Beatles fan, and 20 years ago Michael Lindsay, the director of the Beatles documentary “Let it Be,” called us out of the blue and asked to be put on our mailing list—and we still still talk to him. I love it when that sort of thing happens.

And of course, working on uniforms for 42 was a great experience for me personally. Jackie Robinson is part of the DNA of our company: Growing up in Brooklyn, my dad would tell me stories of Jackie Robinson and from there I learned about the Negro Leagues; it’s a springboard to everything we do. So getting to work on that movie, taking my dad to the premier, and seeing our work up on the screen—that was really special.

0 notes