#charles i of england

Text

#no context horrible histories#horrible histories#charles i#Charles i of England#mathew baynton#mat baynton#the six idiots

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641)

Charles I of England and Queen Henrietta Maria, 1632

Arcibiskupský zámek a zahrady v Kroměříži

Sir Anthony van Dyck was a Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Spanish Netherlands and Italy.

#Anthony van Dyck#flemish#1600s#english#england#charles i of england#queen henrietta maria#art#queen#king#fine art#fine arts#oil painting#flemish art#flanders#portrait#european history#europe#france#scotland#europa#european#western civilization#king of england#queen of england#history

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

He really does look to be on the verge of tears in every portrait.

He really looks as though he couldn’t say boo to a goose!

I hate to say it, but based on these portraits it’s very unsurprising that he was overthrown.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of King Charles I with M. de St Antoine | Anthony van Dyke | 1633

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parliament Loses the Initiative: ‘It Was Easy to Begin the War, but No One Knew Where it Would End’

The King Resurgent

Second Battle of Newbury by Pieter Meulener. Source: Newbury History

MARSTON MOOR arguably changed the nature and course of the war in a number of ways. It was a huge Parliamentary victory, in a conflict which had not seen many Roundhead triumphs to date. It therefore gave the Parliamentary government real hope that they could defeat the King’s forces and require Charles to discuss a new settlement on Parliament’s terms. It was also the bloodiest battle that the war had seen, with large casualties and vicious fighting: if until that point the war still had an air of being conducted by gentleman amateurs engaged in a family squabble, Marston Moor made the war uncompromising and existential. The battle also resulted in the permanent Parliamentary and Covenanter occupation of the North of England: there would be no Royalist resurgence in the North. However, for all its significance, Marston Moor was not decisive, and the ineptitude of the Parliamentary war effort in the late summer and autumn of 1644, allowed the King back into the contest, and demonstrated clearly that Parliament’s informal and aristocratic led military structure was unlikely to bring the war to a successful conclusion.

Parliament’s response to the stunning victory at Marston Moor in the August of 1644, was that of inactivity. Fairfax and Leven, seemingly content with the capture of York, stayed in the North and made no attempt to press their advantage by moving on the Royalist Midlands; the Earl of Manchester failed to bring his Eastern Association army to the defence of London as Parliament wished, despite the threat of a Royalist invasion of East Anglia having been ended by Marston Moor, and the Earl of Essex, on his own initiative, embarked on a quixotic raid on the West Country, possibly motivated by a desire to secure his place in a postwar government on the assumption the King soon sued for peace. This situation was indicative of the woes at the heart of the Parliamentary military structure - it was divided between powerful landholding commanders who made their own decisions, often in defiance of the Parliamentary civilian leadership and rarely in co-ordination with one other.

Essex’s campaign began with the relief of the sieges of both Lyme and Plymouth, which was in accordance with the wishes of the Committee of Both Kingdoms, but he then marched on Exeter, in the hope of capturing Queen Henrietta Maria, who was in residence there, hoping to use a captive queen to induce the King to negotiate. Henrietta Maria, however, escaped to the continent, and Essex suddenly found himself pressed by a large Royalist army, led by Charles himself out of Oxford, intent on rescuing his wife. Essex found himself trapped between the Royalist assault and the sea. On 31st August, in the heart of Royalist Cornwall, Charles surrounded Essex’s forces at Lostwithiel. Essex realised his position was hopeless. He escaped from the town by fishing boat, ordering 6,000 infantry under Sir Philip Skippon to surrender on the best terms they could, arguing he was too eminent commander to be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy. Skippon sought terms on 2nd September and his army was allowed by Charles to depart for Parliamentary territory, retaining their banners and personal arms. Their retreat however was a miserable affair, with the defeated Roundheads suffering abuse and physical assault from a jeering, triumphant Royalist soldiery.

Despite this unexpected victory, Charles’ strategy remained essentially defensive. The Committe, alarmed at Essex’s ignominious failure, again worried that the King might make a dash for London and try to end the war by overthrowing the Parliamentary leadership. It therefore ordered troops commanded by William Waller, which had previously unsuccessfully tried to prevent the King from re occupying Oxford, to enter Dorset to stymie any Royal advance out of the West Country; Manchester meanwhile finally followed orders and marched the Eastern Association army towards Reading. Charles was as alarmed by these moves as Parliament had been by his own. His main concern was to safeguard Oxford, which meant he was intent on securing Oxfordshire and the passages into Royalist Wales. He was to be helped by a demoralised, but still energetic Prince Rupert, who put together a new army, consisting of the remnants of the Earl of Newcastle’s northern forces combined with a new cavalry troop, called the Northern Horse, led by Sir Marmaduke Langdale. By mid October 1644, therefore, both sides had considerable forces at their disposal. Manchester and Waller combined their armies into a single formation 18,000 men strong, and headed west to engage the Royalists. The armies met again at Newbury on 26th October. The Parliamentarians outnumbered that of the King, who had yet to be joined by Rupert and Langdale, by almost two to one, but the Roundhead attack was hobbled by a joint leadership run by a reactive committee. Manchester came up with an eccentric battlefield strategy involving a separation of his own and Waller’s forces in an attempted pincer movement which was too slow and in the event poorly co-ordinated. Militarily, the Roundheads were found wanting: Cromwell’s cavalry was uncharacteristically ineffective, while Manchester, more typically, failed to press his tactical advantage or deliver his part of his own battlefield strategy. In contrast, the Royalist army fought with skill and bravery and although no side obtained outright victory, it was Charles who extracted his army with relatively few casualties. His Parliamentary opponents were left both frustrated and dispirited.

If the Parliamentary commanders were aware that they lost an opportunity possibly to defeat the King decisively at the second Battle of Newbury, matters were made infuriatingly worse on 9th November, when Charles reappeared outside the town at a settlement called Speenhamland and offered battle again. There was some skirmishing, but Manchester refused to attack, unnerved by the presence of Rupert’s new army, much to the chagrin of Oliver Cromwell*, which allowed Charles to proclaim victory. He then led his forces to the relief of Banbury, thus securing the approach to his capital. Going into winter quarters in Oxford in late November 1644, the resurgent King could look back on the autumn with some satisfaction. Despite the loss of the North, he had consolidated Royalist control of the West and Wales and, reinforced by his nephew, was still in striking distance of London. Royalist hopes of prevailing in the conflict remained undimmed, despite the shock of Marston Moor. However, morale within the Committee was much less high. The Commons fell into mutual recrimination as to how a war that had seemed all but won in August, could have returned to uncertainty and genuine fear of an ultimate Royalist victory.

For some time, MPs had, very broadly, been divided into a “Peace Party” and a “War Party”. The former wished for an early negotiated end to the conflict that would see the withdrawal of an imposed Book of Common Prayer, the establishment of fixed Parliamentary sessions and formalised Parliamentary influence on the running of the Kingdom, but would nonetheless re-establish a loyal partnership between the King and his Parliament within a new constitutional settlement. The latter, however, although it fundamentally distrusted Charles personally, it also believed monarchical authority as exercised by James and Elizabeth before him, was unacceptable, leading to religious persecution and the end of meaningful role of Parliament in the governance of the Kingdom. It wished to see complete military victory over Charles, after which a new settlement, in which the monarch would undertake an essentially symbolic role and power would be vested in the Commons, could be dictated to the King. The events of 1644 however, opened up new and significant divisions. The Solemn League and Covenant may have brought the Scots into the war on Parliament’s side, but the price to be paid - the introduction of Presbyterianism as the only recognised form of worship in the two kingdoms - was considered too high by the majority of English Parliamentarians who were neither Episcopalians nor extreme Presbyterians. This group increasingly referred to themselves as “Independents”, reflective of newer, more primitive, forms of Calvinist religion that many of them espoused. They were as determined to frustrate the aims of the Covenanters as the Scots were to see the bargain upheld. The Independents would become an increasingly vocal and influential faction as the war and its associated politics progressed.

The final division was more practical. It was one exemplified by the dilettante aristocrats the Earls of Essex and Manchester on one side and the competent soldiers Cromwell and Waller on the other. For the latter, Essex’s defeat in Cornwall and Manchester’s wasted opportunity at second Newbury, were unforgivable and went to the heart of why Parliament remained in danger of losing the war. In the view of these up and coming members of the militarised gentry, the war could no longer be conducted by gifted (or not so gifted) amateurs. The Parliamentary forces needed to become truly national, under a unitary command and characterised by discipline and professionalism. As the winter of 1644/45 commenced, the stage was to be set for the emergence of the New Model Army.

* Cromwell claimed in the furious debates on the failures in the West, that Manchester explained his refusal to engage the King at Speenhamland thus: “If we beat the King ninety nine times, he will still be our King and we his subjects. If he beats us but once, we shall all be hanged.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles I of England sounds exhausting. He did so much to get so many groups of people to hate him and eventually execute him. He does not make being king look worth it.

#grind culture is a grind#charles I of england#kings#monarchy#england#ugh why?#lol the mobs of london have turned on the king AGAIN

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles I of England (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649)Charles I was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of Scotland, but after his father inherited the English throne in 1603, he moved to England, where he spent much of the rest of his life.

Charles II of England(29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685)Charles II was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685. Charles II was the eldest surviving child of Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland and Henrietta Maria of France.

Charles III (November 14, 1948 -presents (age 73 years)Charles III is King of the United Kingdom and 14 other Commonwealth realms. He acceded to the throne on 8 September 2022 upon the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that while he was in Spain, King Charles I of England (who was Prince of Wales at the time) sat for the famous Spanish painter Diego Velazquez? I didn’t know this either until recently. Unfortunately, the portrait has been lost due to time.

It was also his visit to Spain that made Charles a lover of art.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles getting cancer is actually comical to me.

Imagine the only purpose you have in this life, the only reason you were born is to be king. That’s it, that’s all you have. IS TO BE KING. You were told from childhood that you one day would rule England after your mother. So you wait and wait. You wait for 59 YEARS. Because your 96 year old mother hasn’t carked it yet. THEN she finally kicks the bucket, you’re finally king at 73 years old. Congratulations. Your life purpose has finally happened. But not even two years in ASS CANCER beats you. What a life huh?

It’s a our princess coming through for the win.

#funny#joking#self depreciating memes#meme#memes#self depreaction#jokes#i think im funny#humor#i’m funny#self depreacting#England#prince charles#king#british royal family#princess diana#King Charles

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

every time I read about this Disney vs DeSantis thing and the bit about how the agreement doesn't end “until 21 years after the death of the last survivor of the descendants of King Charles III, king of England" all I can think about is some bumbling caper where the Florida government repeatedly tries to assassinate the entire royal family just to spite Disney

#ron desantis#desantis#disney#disney vs desantis#royal family#king charles 3rd#royalty#king charles the third#current events#florida#for the purposes of this bit the Florida Republican's primary weapon is gators#trained gator snipers on every roof top#are those snipers who shoot out gators or gators that are snipers? you decide#would you not you pay to see a movie where a Florida gator chases King Charles through the palace?#you would#don't lie#anyway is Disney evil in many ways? yes#am I also hoping Disney DESTROYS DeSantis in this? also yes#king of england

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

My Queen, My Love: A Novel of Henrietta Maria by Elena Maria Vidal

"Packed with research, the story provides an in-depth look into the marriage between the sister of the French king and the newly crowned English king. It’s a story highlighting the new queen’s struggle in a land with a different language and calendar, not to mention religion. As a devout Catholic, the queen finds herself at odds with a country of Protestants." —Novels Alive

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B09L6KTC2H/ref=as_sl_pc_as_ss_li_til?tag=httpteaattria-20&linkCode=w00&linkId=9bdca3e14ea9f1b8c2061ca322551996&creativeASIN=B09L6KTC2H

0 notes

Text

Monarchies are only fun in fiction. But overthrowing a monarchy in real life could be very fun

#uk politics#king charles news#bbc#england#english politics#we should have stolen all our stuff back from the museum when they werent looking#princess diana#kate middleton#camilla#charles#king#queen#down with the monarchy#i was secretly hoping King Arthur would come back at that moment#could you imagine#uk#politics#uk police#scotland

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

just tumblr things

#i feel like someone’s probably already made this but whatever#royal family#king charles iii#crab rave#tumblr stuff#england#pls let us have another event like september 8th that would b so so funny#if he dies some crazy fandom thing has 2 happen at the same time#meme#homemade memes

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

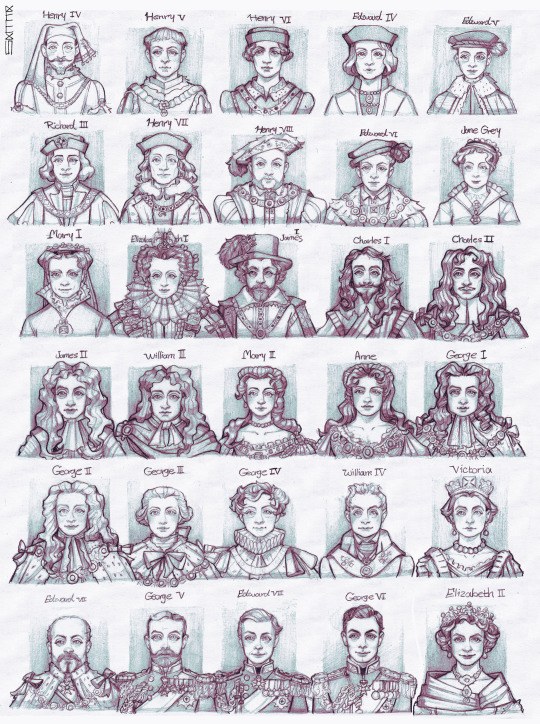

Something I had done years ago on A4 size paper. I think I skipped a few due to lack of space. Kings and Queens of England (after king Henry IV)

#kings of england#artists on tumblr#drawing#traditional art#traditional drawing#Richard III#Henry VII#Henry VIII#Mary I#Elizabeth I#Charles I#Charles II#George III#George IV#Queen Victoria#George v#George VI#Edward VII#queen elizabeth ii#history art

683 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you’re going to have to start on them William coins and notes huh…

#can’t wait for another monarch death viewing party with the besties#was in the middle of bleaching my hair when I saw that that ugly fuck has cancer#what a beautiful moment#ireland#irish#King Charles#king charles iii#monarchy#british royal family#British monarchy#uk#united kingdom#england#britain#British#news#politics

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Stuart and his Kingdoms: ‘Never Make Defence or Apology’

Charles I Ascends His Throne

Charles Stuart, King of Scotland, England and Ireland

Portrait by Anthony van Dyck (1636)

CHARLES STUART, Duke of Albany and Earl of Ross, never expected to become King of the United Kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. He was the second son of King James VI of Scotland who, on the death of Queen Elizabeth I, became King James I of England, uniting the British crowns for the first time in history. Sickly, lonely and shy, Charles Stuart was looked down upon by his flamboyant older brother Prince Henry and starved of love by his reserved mother, Queen Anne of Denmark. Born in 1600, the bookish Charles, beset with ill health, lived in the shadows of King James’ boisterous court, but was suddenly thrust into prominence when Henry unexpectedly died in 1612 at the age of eighteen, to make Charles heir to the thrones of the United Kingdoms. James’ tuition of Charles to prepare him for his future role, was haphazard, but two aspects of this preparatory education became entirely formative and shaped Charles’ attitude to governance. One was a strong endorsement of High Church Anglicanism: undeniably Protestant, but one that maintained many of the organisational and liturgical forms of Roman Catholicism. The other was a devoted adherence to the philosophy of the Divine Right of Kings, a self justificatory belief system, strongly held by James, that monarchs were essentially anointed by God to rule and could brook no secular or religious barriers to their ability to do so. Anglicanism and the Divine Right were abiding principles which would define Charles’ dealings with the three kingdoms, their Parliaments and their religious representatives.

Charles ascended the throne in 1625 on the death of his father, and inherited a difficult foreign policy situation. What was to become the Thirty Years War - the Europe wide struggle between a resurgent Catholicism, championed by the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperors and the German Protestant states - had broken out in 1618 with an imperial attack on Frederick IV, the Elector Palatine and Protestant states’ nominee for the throne of Bohemia, leading ultimately to the defeat, flight and exile of Frederick and his wife, Charles’ sister, the energetic and strong willed Elizabeth, in 1620. This plunged the Kingdoms into war with the Catholic powers of Austria and Spain and a disastrous attack on Cadiz masterminded by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, favourite of James I and dazzling mentor to the impressionable new king, Charles, ensued. The disaster bankrupted the realm’s war effort and led Charles to call his first Parliament in order to be granted funds to replace the losses incurred at Cadiz.

Parliament, although by no means representative of popular will, nonetheless had, since medieval times, acted as a restraint on unrestricted royal power and had come to represent the views to the monarch, of the aristocracy, the gentry and the bishops. The English Parliament in particular strongly defended its right to scrutinise royal actions and to make grants of funds conditional upon the monarch hearing, and hopefully acting on, Parliamentary petitions and advice. The Stuarts, however, inherited a chaotic financial situation. Elizabeth I had run up huge debts and had refused to modernise the wealth taxes from which Parliamentary subsidies to the Crown were derived, to reflect the rampant inflation of recent decades. This meant the state was financially challenged even without the burden of foreign wars. James had attempted to increase wealth taxes, which led to disputes with the few Parliaments that he called. A traditional subsidy granted by Parliament to new monarchs was “tonnage and poundage” a customs duty granted in perpetuity to the monarch to provide the Crown with a revenue stream independent thereafter of Parliamentary approval. The 1625 Parliament however opted to grant Charles tonnage and poundage for one year only, possibly as a means to pressure the young king to discuss tax issues. However Charles, displaying the impatience and high handedness that was to characterise his relationship with Parliament, viewed this decision as a calculated insult.

This mutual antipathy was further increased when Parliament made moves to impeach Buckingham due to his incompetent prosecution of the war against Spain. This fury against a man most Parliamentarians viewed as a dangerous and egotistical fool,was compounded by Buckingham’s insistence that the English navy land a force at La Rochelle, to relieve a force of Huguenots besieged there. This grandiose plan brought England into dispute with France, and a further front in its war against the Catholic powers of Europe. The attempt to relieve La Rochelle proved to be an unmitigated disaster and the beginning of the end for Buckingham. However, before Parliament could summon Villiers to face its censure, the Duke was murdered at Portsmouth by a disgruntled sailor, angry at having been passed over for promotion. The death of Buckingham could have presaged a new start for the King’s poor relationship with Parliament but after Villiers’ death, which hit the young man hard, Charles found himself drawn to a man almost as inflexible and ideological as himself: the Bishop of London, William Laud.

Laud was an advocate of Arminianism - a High Church belief strongly opposed to Calvinism that supported the role of bishops in the running of the Protestant church as opposed to the religious assemblies that governed the Presbyterian communities of lowland Scotland. Laud urged the King to achieve uniform episcopacy (religious administration headed by bishops) across all his kingdoms, and found a ready listener in Charles. By this time, however, the religious revolution that occurred during the reign of Edward VI had established a strong vein of Calvinism within the English church too and which found its expression in “Puritanism” a pejorative term for Low Church Calvinists who viewed the Reformation as not only incomplete, but under attack from recidivist Anglicanism. The religious disputes that were about to escalate were to dwarf those of finance and the constitution that had hitherto formed the fault lines between the King and his subjects.

In the meantime, Charles had dissolved two rebellious Parliaments and sought to raise funds for his wars through extra Parliamentary means, principally “enforced loans” on the gentry, comprising an estimate of the tax an individual could afford by the royal government, followed by a demand for payment. This reinterpretation of Tudor law led to significant opposition and the eventual publication of the “Petition of Right”, drawn up by an MP named Sir Edward Coke. The Petition comprised a restatement of existing law that forbade taxation without Parliamentary authorisation, banned martial law and upheld habeus corpus. At Charles’ third Parliament in 1629, the King accepted the Petition, but there nonetheless ensued a fierce debate in the Commons on the King’s right to raise money directly in contradiction of the Petition of Right. This culminated in MPs holding of the Speaker in his chair in the House when he attempted to leave what he believed to be a treasonous discourse, so the debate could legally continue. A furious Charles dissolved Parliament once again and ordered the arrest of three MPs who had been most closely involved in the prevention of the Speaker leaving the chamber. One of the arrested men, Sir John Eliot, refused to pay the resultant fines and died in prison in 1632, the first Parliamentary martyr in the long dispute with the King.

With the dissolution of the 1629 Parliament, Charles embarked on his “Personal Rule”: a period of eleven years in which there was no Parliament to thwart his wishes However, the disputes between the King and his subjects concerning the rule of law and the governance of the Churches of England and Scotland, had only just begun.

6 notes

·

View notes