#chinese fashion history

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms Period Traditional Clothing Hanfu

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

Brick with portraits of people playing music and dancing unearthed from Feng Hui(冯辉)'s tomb,Bin County Cultural Collection, China.

【China Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms Period Musician and Dancer Garment 】

During the Five Dynasties period, the development of costume art showed a trend like “hundred flowers bloom”

At that time, clothing styles were diverse and there were fewer restrictions and constraints, and bolder artistic exploration began. On the one hand, the development of fine arts and aesthetic theories during the Tang and Song Dynasties also injected vigorous vitality into the art of clothing; on the other hand, the skills passed down from previous generations gave clothing a richer and more diverse style.

These influences, inherited from previous dynasty, became an important part of the fashion at that time and gradually developed into a classic paradigm. Among them, the long-skirt style attire originated from the late Tang Dynasty is still widely popular and favored by women. When matching this type of shirt and skirt, they often wear their hair in a tall and unique bun, creating a taller and slender silhouette. This style was inherited from the late Tang Dynasty and incorporated into the new trends of the times, making it appear solemn and beautiful.

This garment refers to the brick carvings of Feng Hui's tomb and restores the image of musicians from the Five Dynasties and later Zhou Dynasties. Their hair is in a high bun, their temples are hugging their faces, their hair is tied at the top, and they are decorated with precious pearls. They wear blouses and long skirts, and appear to be light and swaying in their steps. They have the beauty of smart, pretty, harmonious and elegant rhythm.

#chinese hanfu#five dynasties and ten kingdoms period#late zhou dynasty#hanfu#hanfu history#hanfu accessories#Chinese fashion history#Chinese#chinese history#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#Chinese hairstyles#漢服#汉服#中華風#chinese style#chinese art

265 notes

·

View notes

Note

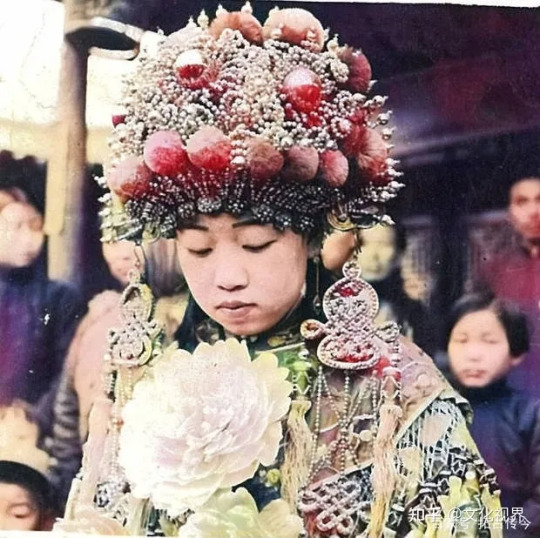

Hi my friend wanted to ask about Chinese Opera and the red pom poms on their hats and their significance. I asked my mom and she said they were for decoration so I just wanted clarification

Hi! Thanks for the question, and sorry for taking ages to reply!

The pom poms you see on 盔头/kuitou (Chinese opera headdresses) are called 绒球/rongqiu (lit. "velvet ball"). They are often red, but can also be other colors, and vary in size. Ronqiu are decorative and serve to distinguish the many different types of kuitou from one another. Each type of kuitou is distinct in the number, size, and color of rongqiu that it's decorated with (of course, not all kuitou have rongqiu).

Below - a few different types of Beijing opera kuitou decorated with rongqiu (x):

Rongqiu isn't used just for Chinese opera performances - it's a very common decorative item for Chinese headwear, especially for traditional/folk performances.

Below - examples of rongqiu use in folk custom/performance costumes, left to right: 1) 游神/youshen (wandering gods) procession in Fujian (x), 2) 英歌舞/yingge wu (yingge dance) performer in Guangdong (x), 3) & 4) 高跷/gaoqiao (stilt walking) performers in a 社火/shehuo parade in Gansu (x):

As a festive decoration, rongqiu was also widely used on bridal guan (crowns) from the Qing dynasty into the modern day.

Below - examples of rongqiu use in historical bridal guan: Left - a bride during the late Qing dynasty, circa 1890 (x); Right - a bride during the Republican era/minguo, in 1939 (x):

For some reason it's been extremely difficult to find sources on the origin of rongqiu that would shed more light on its significance, but based on historical paintings the use of rongqiu as a head ornament may have originated in the Qing dynasty. During the late Qing dynasty, it was fashionable among women to wear rongqiu on the sides of their hair, as can be seen in the paintings below (x):

This particular style of rongqiu hair ornament was depicted in the 2012 historical cdrama 娘心计/Mother's Scheme:

For more references, please see my rongqiu and kuitou tags.

If anyone has more information on the significance of rongqiu, please do share!

Hope this helps ^^

#rongqiu#pompoms#kuitou#chinese opera#opera costume#xifu#hanfu#history#reference#ask#reply#junpeicindystories#chinese fashion#chinese clothing#china

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

chinese guzhuang fashion

#young actress and actors are cornering the guzhuang market#that's why the industry is becoming more and more competitive#when it comes to guzhuang idol dramas/guouju古偶剧 with fantasy elements(like xianxia dramas)#cnetizens are bored with the same old faces#media has found that young actress and actors (20-27 years old) especially new pretty faces are more appealing to viewers#cnetizens can actually be mean to actress and actors (over 33 years old) cast as lead characters in guzhuang idol dramas#reasons is that lead characters are usually portrayed as teenagers or really young people#and the audience find it very weird to have middle-aged people cast such characters#especially scripts are usually adapted based on fictions#so fans of the novels would be furious about such casting#besides cnetizens want to see normal aging faces#but these shows always use excessive filters and PS#causing the midle-aged faces to be fake and weird#i once saw really mean comments on douyin for xianxia dramas casting middle-aged actress getting over one hundred thousand likes#actress and actors in zhengju正剧 guzhuang dramas or luodi落地 guzhuang dramas are not affected by this#like telling a realistic down-to-earth story or story inspired by real history or related to folks#and there is no fantasy or xianxia elements#china#fashion#chinese fashion#guzhuang#cdramas

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

for good omens s3 i hope we get to see crowley with REALLY long hair, waist length or longer. just luxurious long locks pooling around him

#ways i’m imagining this: like historical chinese fashion#ways this is more likely: those stupid 1600s curly wigs#anyway#not to be biased but i like long haired crowley#good omens#mine#not that i Want them to do asian history because i think that might just turn out bad#but i think all those chinese history books my mom made us read as kids rubbed off

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

perhaps a bit of a long shot but since Ik there are a few hanfu people in the audience, does anyone know where I can find a more regional history of clothing? A lot of sources tend to go by class or time period but I can’t find many sources that focus on like ‘history of hanfu in guangdong’ or ‘clothing history in fujian’. Most of the stuff that pops up are specifically focused on ethnic minority or non-han group clothing history which is nice but not quite what i’m looking for :’(

#im on hiatus bc school has started but#just in case….#diary#hanfu#chinese hanfu#hanfu movement#tagging a lot in case there are people in the tags#chinese history#chinese clothing history#hanfu history#chinese fashion#also if anyone comes onto the og post to look. i can read chinese (and japanese to a point but i doubt theres anything lol) so if u have#any chinese sources…. pspspsps :3

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coat, said to have belonged to Empress Dowager Cixi

c.1890-1900 (Qing Dynasty)

China

Royal Ontario Museum (Object number: 919.6.128)

#coat#fashion history#historical fashion#cixi#chinese fashion#non western fashion#1890s#1900s#blue#embroidery#19th century#20th century#silk#satin#empress cixi#empress dowager cixi#royal ontario museum#popular

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

等云来【杜若小胖纸】

#hanfu#hanfu art#traditional clothing#traditional chinese clothing#chinese clothing#china#clothing#culture#history#fashion#art

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Origins of the Pibo: Let’s take a trip along the Silk Road.

1. Introduction to the garment:

Pibo 披帛 refers to a very thin and long shawl worn by women in ancient East Asia approximately between the 5th to 13th centuries CE. Pibo is a modern name and its historical counterpart was pei 帔. But I’ll use pibo as to not confuse it with Ming dynasty’s xiapei 霞帔 and a much shorter shawl worn in ancient times also called pei.

Below is a ceramic representation of the popular pibo.

A sancai-glazed figure of a court lady, Tang Dynasty (618–690, 705–907 CE) from the Sze Yuan Tang Collection. Artist unknown. Sotheby’s [image source].

Although some internet sources claim that pibo in China can be traced as far back as the Qin (221-206 BCE) or Han (202 BCE–9 CE; 25–220 CE) dynasties, we don’t start seeing it be depicted as we know it today until the Northern and Southern dynasties period (420-589 CE). This has led to scholars placing pibo’s introduction to East Asia until after Buddhism was introduced in China. Despite the earliest art representations of the long scarf-like shawl coming from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, the pibo reached its popularity apex in the Tang Dynasty (618–690 CE: 705–907 CE).

Academic consensus: Introduction via the Silk Road.

The definitive academic consensus is that pibo evolved from the dajin 搭巾 (a long and thin scarf) worn by Buddhist icons introduced to China via the Silk Road from West Asia.

披帛是通过丝绸之路传入中国的西亚文化, 与中国服饰发展的内因相结合而流行开来的一种"时世妆" 的形式. 沿丝绸之路所发现的披帛, 反映了丝绸贸易的活跃.

[Trans] Pibo (a long piece of cloth covering the back of the shoulders) was a popular female fashion period accessory introduced to China by West Asian cultures by way of the Silk Road and the development of Chinese costumes. The brocade scarves found along the Silk Road reflect the prosperity of the silk trade that flourished in China's past (Lu & Xu, 2015).

I want to add to the above theory my own speculation that, what the Chinese considered to be dajin, was most likely an ancient Indian garment called uttariya उत्तरीय.

2. Personal conjecture: Uttariya as a tentative origin to pibo.

In India, since Vedic times (1500-500 BCE), we see mentions in records describing women and men wearing a thin scarf-like garment called “uttariya”. It is a precursor of the now famous sari. Although the most famous depiction of uttariya is when it is wrapped around the left arm in a loop, we do have other representations where it is draped over the shoulders and cubital area (reverse of the elbow).

Left: Hindu sculpture “Mother Goddess (Matrika)”, mid 6th century CE, gray schist. Artist unknown. Looted from Rajasthan (Tanesara), India. Photo credit to Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States [image source].

Right: Rear view of female statue possibly representing Kambojika, the Chief Queen of Mahakshatrapa Rajula, ca. 1st century CE. Artist unknown. Found in the Saptarishi Mound, Mathura, India. Government Museum, Mathura [image source].

Buddhism takes many elements from Hindu mythology, including apsaras अप्सरा (water nymphs) and gandharvas गन्धर्व (celestial musicians). The former was translated as feitian 飞天 in China. Hindu deities were depicted wearing clothes similar to what Indian people wore, among which we find uttariya, often portrayed in carvings and sculptures of flying and dancing apsaras or gods to show dynamic movement. Nevertheless, uttariya long predated Buddhism and Hinduism.

Below are carved representation of Indian apsaras and gandharvas. Notice how the uttariya are used.

Upper left: Carved relief of flying celestials (Apsara and Gandharva) in the Chalukyan style, 7th century CE, Chalukyan Dynasty (543-753 CE). Artist Unknown. Aihole, Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source]. The Chalukyan art style was very influential in early Chinese Buddhist art.

Upper right: Carved relief of flying celestials (gandharvas) from the 10th to the 12th centuries CE. Artist unknown. Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source].

Bottom: A Viyadhara (wisdom-holder; demi-god) couple, ca. 525 CE. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Nomu420 on May 10, 2014. Sondani, Mandsaur, India [image source].

Below are some of the earliest representations of flying apsaras found in the Mogao Caves, Gansu Province, China. An important pilgrimage site along the Silk Road where East and West met.

Left to right: Cave No. 461, detail of mural in the roof of the cave depicting either a flying apsara or a celestial musician. Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285 flying apsara (feitian) in one of the Mogao Caves. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE), Artist unknown. Photo taken by Keren Su for Getty Images. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 249. Mural painting of feitian playing a flute, Western Wei Dynasty (535-556 CE). Image courtesy by Wang Kefen from The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance, The Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 15. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

I theorize that it is likely that the pibo was introduced to China via Buddhism and Buddhist iconography that depicted apsaras (feitian) and other deites wearing uttariya and translated it to dajin.

3. Trickle down fashion: Buddhism’s journey to the East.

However, since Buddhism and its Indian-based fashion spread to West Asia first, to Sassanian Persians and Sogdians, it is likely that, by the time it reached the Han Chinese in the first century CE, it came with Persian and Sogdian influence. Persians’ fashion during the Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE) was influenced by Greeks (hellenization) who also had a a thin long scarf-like garment called an epliblema ἐπίβλημα, often depicted in amphora (vases) of Greek theater scenes and sculptures of deities.

Left to right: Dame Baillehache from Attica, Greece. 3rd century BCE, Hellenistic period (323-30 BCE), terracotta statuette. Photo taken by Hervé Lewandowski. Louvre Museum, Paris, France [image source].

Deatail view of amphora depicting the goddess Artemis by Athenian vase painter, Andokides, ca. 525 BCE, terracotta. Found in Vulci, Italy. Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany [image source].

Statue of a Kore (young girl), ca. 570 BCE, Archaic Period (700-480 BCE), marble. Artist unknown. Uncovered from Attica, Greece. Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece [image source].

Detail view of Panathenaic (Olympic Games) prize amphora with lid, 363–362 BCE, Attributed to the Painter of the Wedding Procession and signed by Nikodemos, terracotta. Uncovered from Athens, Greece. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, United States [image source].

Roman statue depicting Euterpe, muse of lyric poetry and music, ca. 2nd century CE, marble, Artist unknown. From the Villa of G. Cassius Longinus near Tivoli, Italy. Photo taken by Egisto Sani on March 12, 2012, Vatican Museums, Rome, Italy [image source].

Greek (or Italic) tomb mural painting from the Tomb of the Diver, ca. 470 BCE, fresco. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Floriano Rescigno. Necropolis of Paestum, Italy [image source].

Below are Iranian and Iraqi period representations of this long thin scarf.

Left to right: Closeup of ewer likely depicting a female dancer from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia , Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 10, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Ewer with nude dancer probably representing a maenad, companion of Dionysus from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia, Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 16, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Painting reconstructing the image of unveiled female dancers depicted in a fresco, Early Abbasid period (750-1258 CE), about 836-839 CE from Jawsaq al-Khaqani, Samarra, Iraq. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul [image source].

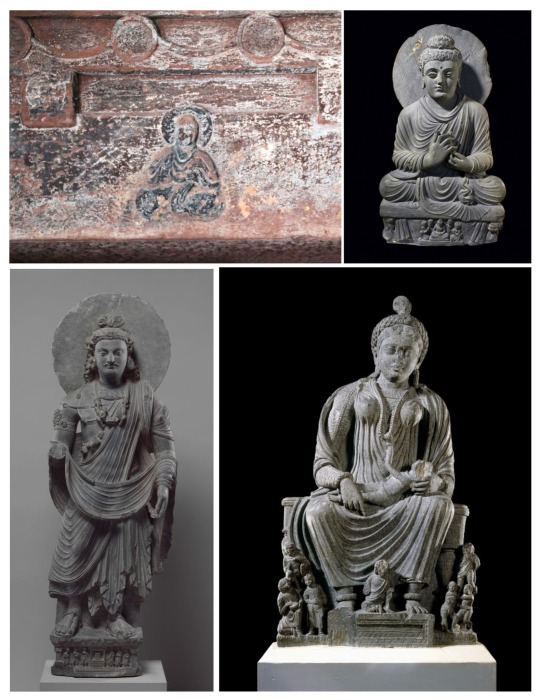

The earliest depictions of Buddha in China, were very similar to West Asian depictions. Ever wonder why Buddha wears a long draped robe similar to a Greek himation (Romans called it toga)?

Take a look below at how much the Greeks influenced the Kushans in their art and fashion. The top left image is one of the earliest depictions of Buddha in China. Note the similarities between it and the Gandhara Buddha on the right.

Left: Seated Buddha, Mahao Cliff Tomb, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han Dynasty, late 2nd century C.E. (photo: Gary Todd, CC0).

Right: Seated Buddha from Gandhara, Pakistan c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Standing Bodhisattva Maitreya (Buddha of the Future), ca. 3rd century, gray schist. From Gandhara, Pakistan. Image credit to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States [image source].

Statue of seated goddess Hariti with children, ca. 2nd to 3rd centuries CE, schist. Artist unknown. From Gandhara, Pakistan. The British Museum, London, England [image source].

Before Buddhism spread outside of Northern India (birthplace), Indians never portrayed Buddha in human form.

Early Buddhist art is aniconic, meaning the Buddha is not represented in human form. Instead, Buddha is represented using symbols, such as the Bodhi tree (where he attained enlightenment), a wheel (symbolic of Dharma or the Wheel of Law), and a parasol (symbolic of the Buddha’s royal background), just to name a few. […] One of the earliest images [of Buddha in China] is a carving of a seated Buddha wearing a Gandharan-style robe discovered in a tomb dated to the late 2nd century C.E. (Eastern Han) in Sichuan province. Ancient Gandhara (located in present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India) was a major center for the production of Buddhist sculpture under Kushan patronage. The Kushans occupied portions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and North India from the 1st through the 3rd centuries and were the first to depict the Buddha in human form. Gandharan sculpture combined local Greco-Roman styles with Indian and steppe influences (Chaffin, 2022).

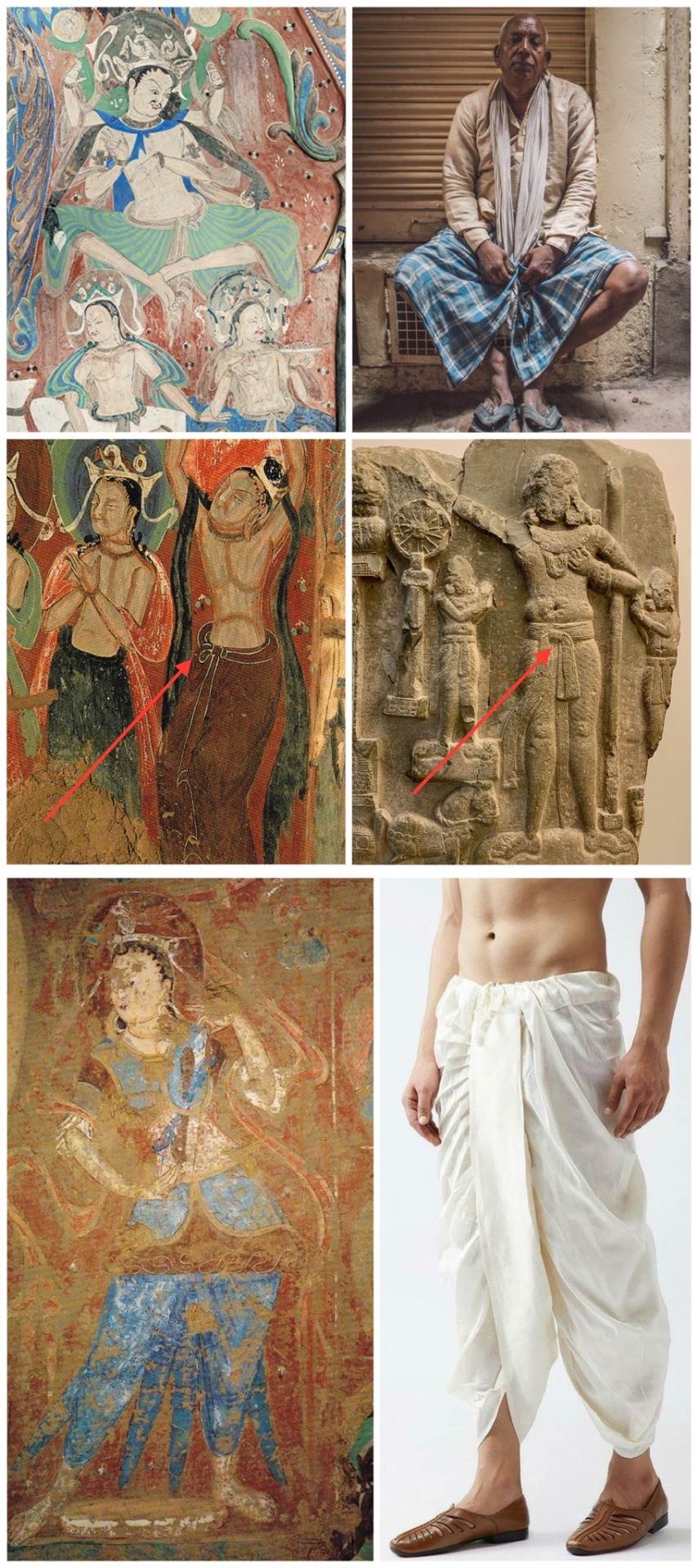

In the Mogao Caves, which contain some of the earliest Buddhist mural paintings in China, we see how initial Chinese Buddhist art depicted Indian fashion as opposed to the later hanfu-inspired garments.

Left to right: Cave 285, detail of wall painting, Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Courtesy the Dunhuang Academy [image source]. Note the clothes the man is wearing. It looks very similar to a lungi (a long men’s skirt).

Photo of Indian man sitting next to closed store wearing shirt, scarf, lungi and slippers. Paul Prescott. February 20, 2015. Varanasi, India [image source].

Cave 285, mural depiction of worshipping bodhisattvas, 6th century CE, Wei Dynasty (535-556 A.D.), Unknown artist. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Notice the half bow on his hips. That is a common style of tying patka (also known as pataka; cloth sashes) that we see throughout Indian history. Many of early Chinese Buddhist paintings feature it, including the ones at Mogao Caves.

Indian relief of Ashoka wearing dhoti and patka, ca. 1st century BC, Unknown artist. From the Amaravathi village, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Currently at the Guimet Museum, Paris [image source].

Cave 263. Mural showing underlying painting, Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535 CE). Artist Unknown. Picture taken November 29, 2011, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source]. Note the pants that look to be dhoti.

Comparison photo of modern dhoti advertisement from Etsy [image source].

Spread of Buddhism to East Asia.

Map depicting the spread of Buddhism from Northern India to the rest of Asia. Gunawan Kartapranata. January 31, 2014 [image source]. Note how Mahayana Buddhism arrived to China after passing through Kushan, Bactrean, and nomadic steppe lands, absorbing elements of each culture along the way.

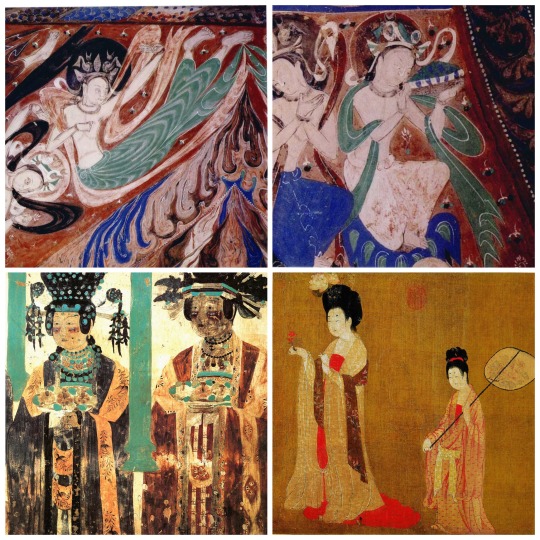

Wealthy Buddhist female patrons emulated the fantasy fashion worn by apsaras, specifically, the uttariya/dajin and adopted it as an everyday component of their fashion.

Cave 285. feitian mural painting on the west wall, Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285. Detail view of offering bodhisattvas (bodhisattvas making offers to Buddha) next to the phoenix chariot on the Western wall of the cave. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 61 Khotanese (from the kingdom of Khotan 于阗 [56–1006 CE]) donor ladies, ca. 10th century CE, Five Dynasties period (907 to 979 CE). Artist unknown. Picture scanned from Zhang Weiwen’s Les oeuvres remarquables de l'art de Dunhuang, 2007, p. 128. Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons on October 11, 2012 by Ismoon. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Detail view of Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers 簪花仕女图, late 8th to early 9th century CE, handscroll, ink and color on silk, Zhou Fang 周昉 (730-800 AD). Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China [image source].

Therefore, the theory I propose of how the pibo entered East Asia is:

India —> Greek influenced West Asia (Sassanian Persians, Sogdians, Kushans, etc…) —> Han China —> Rest of East Asia (Three Kingdoms Korea, Asuka Japan, etc…)

Thus, the most likely theory, in my person opinion, is Buddhist iconography depicting uttariya encountered Greek-influenced West Asian Persian, Sogdian, and Kushan shawls, which combined arrived to China but wouldn’t become commonplace there until the explosion in popularity of Buddhism from the periods of Northern and Southern Dynasties to Song.

References:

盧秀文; 徐會貞. 《披帛與絲路文化交流》 [The brocade scarf and the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road]. 敦煌研究 (中國: 敦煌研究編輯部). 2015-06: 22 – 29. ISSN 1000-4106.

#hanfu#chinese culture#chinese history#buddhism#persian#sogdian#kushan#gandhara#indian fashion#uttariya#pibo#history#asian culture#asian art#asian history#asian fashion#east asia#south asia#india#pakistan#iraq#afghanistan#sassanian#silk road#fashion history#tang dynasty#eastern han dynasty#cultural exchange#greek fashion#mogao caves

283 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Chinese Hats and Headwear in the Three Kingdoms 1994 and its history

One of our contributors @csarracenian has subtitled another educational video about the history of various hats and headwear in the 1994 Romance of the Three Kingdoms, explaining their history and meaning and showcasing the high research quality of the show.

Video is made by 是椰果啊 on bilibili & released with their permission.

#three kingdoms#chinese drama#dynasty warriors#chinese history#hanfu#historical#period drama#romance of the three kingdoms 1994#rotk#汉服#冠#history#clothing history#fashion history#ancient china

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

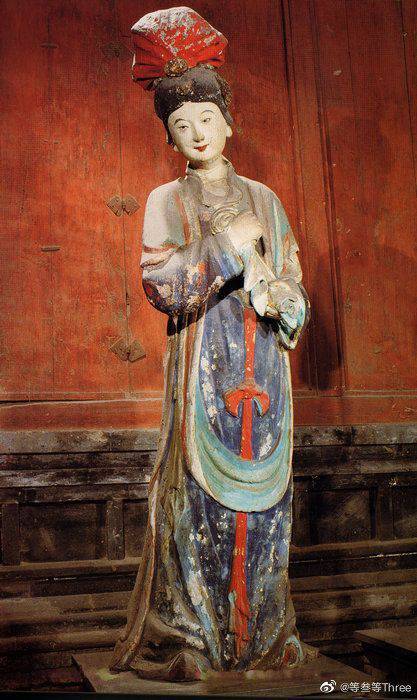

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Reference to Song Dynasty Sculpture

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

China Song Dynasty Painted Sculpture from【Jin Temple】晋祠宋代彩塑

▶️【About Hairstyle“包髻/Bao Ji”】:

It is one of the hairstyles of ancient Han women.

包髻/Bao Ji is a hairstyles that use rectangular headscarf to cover the hair. When worn, it is folded diagonally, wrapped from the front to the back, and then wrapped around the corner of the scarf to the front of the forehead to tie a knot.

As early as the Tang Dynasty(618-907 AD), there was a prototype of this hairstyle, and it became popular in the Song Dynasty.

Women in the Ming Dynasty(1368-1644 AD) liked to use black gauze to make this hairstyle and this kind of hairstyle survived until the last dynasty of China: the Qing Dynasty.

#chinese hanfu#Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#chinese history'#chinese fashion history#chinese historical hairstyle#chinese art#漢服#汉服#中華風#包髻/Bao Ji#Jin Temple

208 notes

·

View notes

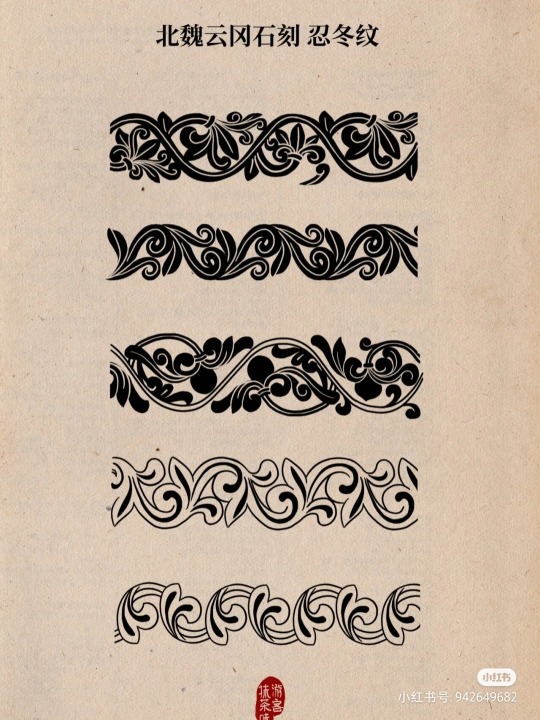

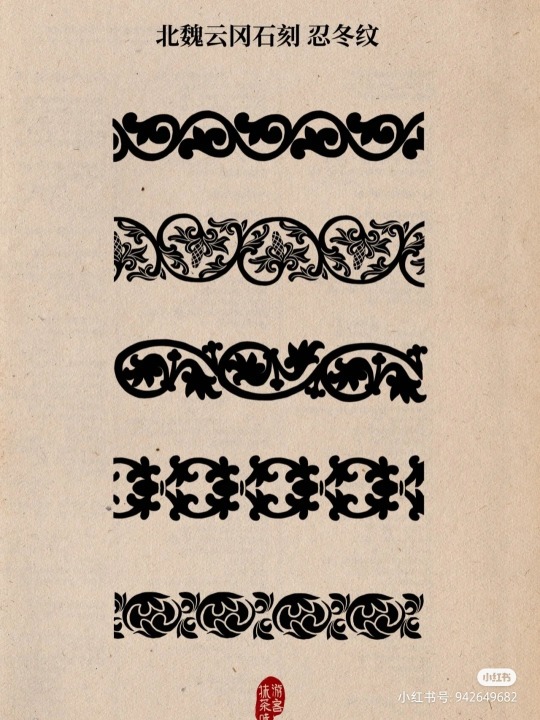

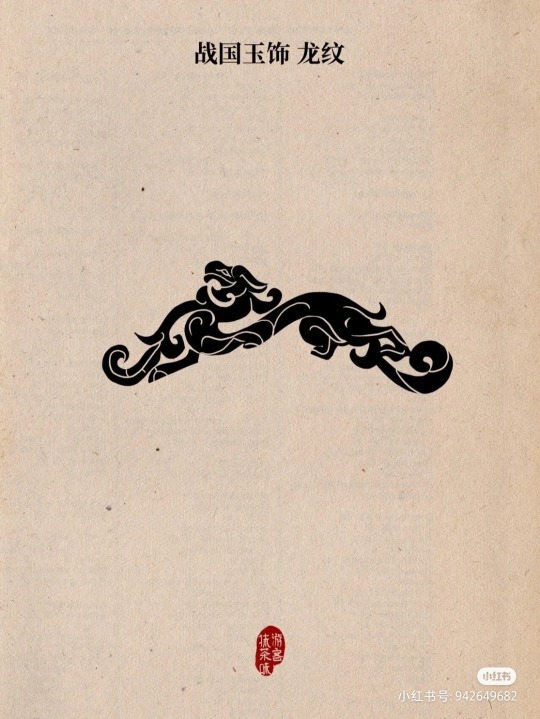

Photo

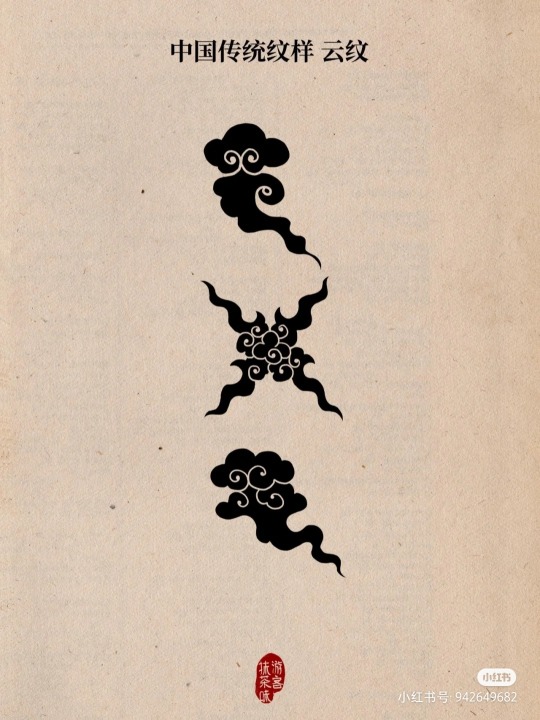

traditional chinese patterns

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine being rich and paying for bland minimalist textiles and cold sterilized homes when you could be paying folk artists handsomely for handcrafted beauty and color —helping preserve honestly quite priceless artistic traditions and supporting the people who keep these legacies alive— instead.

#you have all the ability to buy pieces of art with vibrant histories and made with the worlds most skilled hands#to own something gorgeous and genuine and guarantee that these art forms survive and the people who provide them are well-cared for#and you’d rather live in a hospital and wear three colors all your life#Persian rugs?#traditional Bengali Jamdani fabrics? old school banarasi’s made by hand?#Guatemalan upholstery?#Romanian embroidered blouses?#Japanese-sourced furniture made with ancient joinery techniques?#Chinese porcelain made the old-fashioned way?#gold finery from east Africa?#Czech glass vases?#Navajo blankets?#Vietnamese embroidered thread ‘paintings’?#COME OOOOONNN#rich people learn how to spend your money or give it to me

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

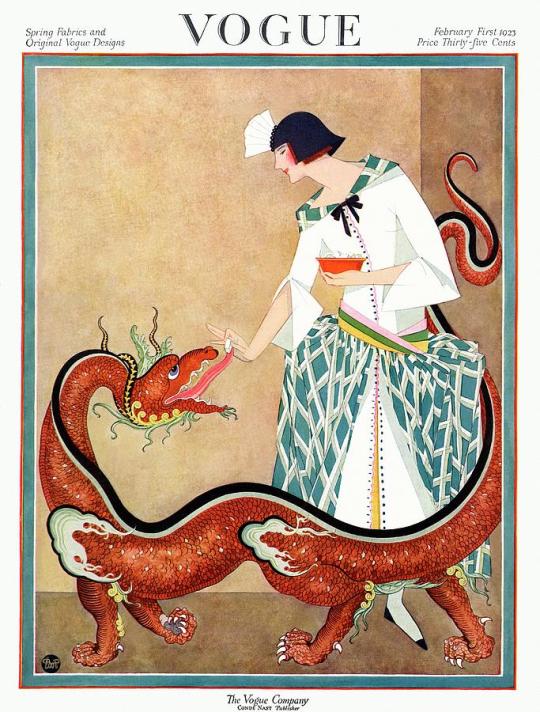

Vogue Cover Of A Woman With A Chinese Dragon

Artist: George Wolfe Plank

February 1st, 1923

#orientalism#art#painting#fashion#art history#illustration#vogue#cover#magazine#1920s#fashion history#George Wolfe Plank#art nouveau#chinese

222 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dress

c.1850

Made of Chinese patterned silk, this dress uses an export textile in a Western garment. Arguably, Asian textiles were associated in the Western mind as much with private leisure as with ceremony. Many Eastern textiles entered Western dress first as intimate boudoir and other at-home garments such as robes and banyans, suggesting the qualities of exoticism and erotic mystery associated with far-off lands. The selvage at the back waist reveals Chinese characters, indicating the textile's manufacture, and the flaring sleeves are what the West calls the pagoda style.

The MET

#fashion history#historical fashion#1850s#crinoline era#victorian fashion#dress#victorian#british#1850#united kingdom#19th century#red#silk#chinese#the met#popular

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

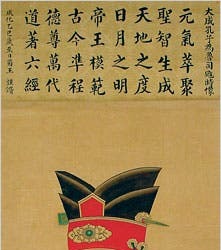

Hello everyone! As a Chinese person interested in hanfu, I have a question. Does anybody know what crown is the Chinese philosopher Confucius wearing in these portraits? Thank you!

#hanfu#chinese#chinese history#ancient china#china#warring states era#warring states period#chinese fashion#hanfu accessories#hanfu movement#tang dynasty#han dynasty#qin dynasty#ming dynasty#chinese hanfu#chinese culture

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abridged History of Qing Dynasty Han Women’s Fashion (part 5: Late Qianlong & Jiaqing eras)

(artwork from 1782)

Previous posts:

Late Ming & Shunzhi era

Kangxi era

Late Kangxi & Yongzheng eras

Qianlong era

The last two decades of the Qianlong era, the 1780s and 90s, formed one aesthetic continuity with the reign of Qianlong’s successor Jiaqing (1796-1820). This period was characterized by a turn to extreme formal simplicity and what I believe to be a revival of the tastes of the Ming-Qing transition.

We see sleeves of women’s robes, tight fitting and short to create a practical look in the previous era, become wider and longer. The folded cuff design was retained, though now more difficult to manage as the sleeves became wider. In the last post I discussed how the construction of dajin similar to Manchu men’s fashion became en vogue among Han women and replaced the earlier center front closing robes----this remained the same. We see some of the first instances of binding strips being used around the collar and the dajin, which would become a highly popular and elaborate craft later in the 19th century. Around this time, the binding strips used were usually thin and minimal, commonly of a black color. Plain cloth or bead tip buttons were popularized earlier in the Qianlong era, and metal clasp buttons (zimukou) became increasingly rare. The shape of the standing collar remained the same as that of previous centuries, soft, unstiffened and tall.

Artwork from 1796 showing a group of courtesans. You can see the black binding on some of their robes. A note about the dating of this artwork: while it’s quite a common reference image for Jiaqing era fashion, I wasn’t able to find an exact date until I read about it in the book Pictures for Pleasure and Use by James Cahill (spectacular book discussing the importance of vernacular and commercial art, highly recommend) and he said the date of creation was signed in the cyclical calendar and corresponds to either 1736 or 1796. He was inclined to 1736 because of “similar face shapes” or something to Yongzheng era artworks, but since he wasn’t a fashion historian he probably wasn’t aware that the fashions depicted here would not have been possible before the 1780s, so I think 1796 is instead the correct date.

Late Qianlong/early Jiaqing era artwork, showing two austerely (and fashionably) dressed women.

The more radical departure from the previous era, however, was the complete eradication of ornament. Robes and skirts of this era were often entirely plain, with no brocaded patterns or embroidery of any kind. Gone were the roundel patterns, quatrefoil motifs on collar facings and decorative strips around skirts----only solid color blocks remained. Pastel colors like light pink, blue and green were among the most popular for robes besides bright blue and red, whereas skirts were white or black.

Late Qianlong/early Jiaqing era paintings of the Anglo-Chinese school showing the new style of plain garments.

Artwork from the era showing a woman in a light mustard robe with dusty pink cuffs, white skirt and red sash (sashes were still commonly worn).

The other significant changes happened in hairstyling. The 1780s did away with the iconic tall knots of the earlier Qianlong era, instead moving the mass and volume of hair toward the back. We see the re-emergence of the swallow tail. The front of the hair could be middle parted or completely pulled back. Flowers and other ornaments could be worn on the sides of the hairdo, behind the ears. The general shape of hairstyles stressed horizontality rather than verticality, as was the case before.

A 1943 copy of a turn of the 19th century original, showing the front and back of hairstyles.

Bust portrait showing the new hairstyle.

A unique hair accessory of the 1780s and 90s was a new iteration of the mo’e, which now had a sharply pointed triangular front and was worn high on the head instead of at the forehead. I think it became less common as the 19th century approached.

Export artwork showing a woman musician, likely 1770s or 80s as she is still wearing the ornamented, center front closing robes popular in previous decades.

Minimalism was not to last long, however, and soon decorative patterns began to reappear on robes, sleeve cuffs and skirts. Hairstyles began to gain volume and became more puffed, forming a sort of face framing crown. New styles of decorating skirts appeared, with binding going around the qunmen and the edge of each pleat, and embroidery on each individual pleat. The rectangular or circular patterned patch popular prior to the 1780s returned.

Early 19th century export painting at the Brighton Pavilion, maybe 1810s. We can see roundel patterns on the blue robe, embroidery on the cuffs and skirt, and the lady in red wears a pointed mo’e.

Presumably later Jiaqing era artwork, ca. 1810s, showing a group of women. Floral embroidery is present on the sleeve cuffs, the skirts are decorated.

#abridged history of qing dynasty han women's fashion#18th century#19th century#qianlong era#jiaqing era#qing dynasty#chinese fashion#fashion history#regency era

177 notes

·

View notes