#chinese religion

Text

PSA - Don't Treat JTTW As Modern Fiction

This is a public service announcement reminding JTTW fans to not treat the work as modern fiction. The novel was not the product of a singular author; instead, it's the culmination of a centuries-old story cycle informed by history, folklore, and religious mythology. It's important to remember this when discussing events from the standard 1592 narrative.

Case in point is the battle between Sun Wukong and Erlang. A friend of a friend claims with all their heart that the Monkey King would win in a one-on-one battle. They cite the fact that Erlang requires help from other Buddho-Daoist deities to finish the job. But this ignores the religious history underlying the conflict. I explained the following to my acquaintance:

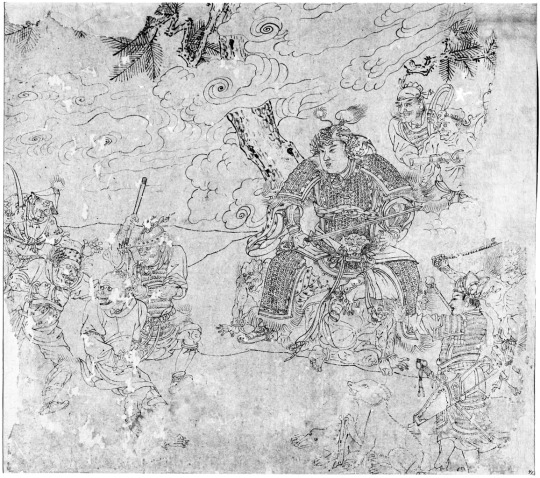

I hate to break it to you [name of person], but Erlang would win a million times out of a million. This is tied to religious mythology. Erlang was originally a hunting deity in Sichuan during the Han (202 BCE-220 CE), but after receiving royal patronage during the Later Shu (934-965) and Song (960-1279), his cult grew to absorb the mythos of other divine heroes. This included the story of Yang Youji, an ape-sniping archer, leading to Erlang's association with quelling primate demons. See here for a broader discussion.

This is exemplified by a 13th-century album leaf painting. The deity (right) oversees spirit-soldiers binding and threatening an ape demon (left).

Erlang was connected to the JTTW story cycle at some point, leading to a late-Yuan or early-Ming zaju play called The God Erlang Captures the Great Sage Equaling Heaven (二郎神鎖齊天大聖). In addition, The Precious Scroll of Erlang (二郎寳卷, 1562), a holy text that predates the 1592 JTTW by decades, states that the deity defeats Monkey and tosses him under Tai Mountain.

So it doesn't matter how equal their battle starts off in JTTW, or that other deities join the fray, Erlang ultimately wins because that is what history and religion expects him to do.

And as I previously mentioned, Erlang has royal patronage. This means he was considered an established god in dynastic China. Sun Wukong, on the other hand, never received this badge of legitimacy. This was no doubt because he's famous for rebelling against the Jade Emperor, the highest authority. No human monarch in their right mind would publicly support that. Therefore, you can look at the Erlang-Sun Wukong confrontation as an established deity submitting a demon.

I'm sad to say that my acquaintance immediately ignored everything I said and continued debating the subject based on the standard narrative. That's when I left the conversation. It's clear that they don't respect the novel; it's nothing more than fodder for battleboarding.

I understand their mindset, though. I love Sun Wukong more than just about anyone. I too once believed that he was the toughest, the strongest, and the fastest. But learning more about the novel and its multifaceted influences has opened my eyes. I now have a deeper appreciation for Monkey and his character arc. Sure, he's a badass, but he's not an omnipotent deity in the story. There is a reason that the Buddha so easily defeats him.

In closing, please remember that JTTW did not develop in a vacuum. It may be widely viewed around the world as "fiction," but it's more of a cultural encyclopedia of history, folklore, and religious mythology. Realizing this and learning more about it ultimately helps explain why certain things happen in the tale.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#jttw#Erlang#Erlang shen#Buddhism#Taoism#Chinese mythology#Chinese religion

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been stricken with numerous personal life circumstances that have made it difficult to produce solid research pieces as well as answer questions, but I still want to share information.

This type of dance is called Dunhuang and mixes traditional ethnic dancing styles with modern art. The style of the dance itself is influenced heavily by Buddhism. Specific body movements are inspired by fresco paintings found inside the caves of the west China province of Gansu. The dance style owes it’s name to the musical scores found within the city of Dunhuang.

Dunhuang itself used to be a massive center for Buddhist teaching and practices between 500AD-1000AD, being home to several monasteries during that time period. Pilgrims from China, India and Tibet would congregate here leaving behind massive amounts of Buddhist written text and art that would form the strongest body of primary works regarding Buddhist communities in China.

This group here is performing The Thousand Handed Guanyin, and actually happen to be hearing impaired! It’s actually quite mesmerizing to watch.

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sun and Moon Pagodas in Guilin, China (photo by Nathan Ackley)

Sun & Moon Twin Pagodas are one of the greatest attractions in Guilin, situated in Shanhu (Shan Lake).

The word sun and moon in Chinese character written together meant brightness. They are also known as Gold and Silver Pagodas because of their colors at night. They stand next to each other reflecting the beauty of each other.

Originally built in Guilin's moat during the Tang dynasty, these tiered towers were reconstructed in 2001 and now they are a tourist site combining culture, art, religion, and architecture, technology, and natural landscape.

The "Sun" Pagoda is constructed with copper; it has 9 floors and reaches a height of 41 metres. The "Moon" Pagoda's construction is made of marble; it has 7 floors and measuring 35 meters high. The two pagodas are connected via a tunnel at the bottom of the lake.

From the Moon Pagoda to the Sun Pagoda, there is a 10-meter glass tunnel that links the two under water. When walking through the tunnel, one can see the fish above the head and on both sides.

#sun and moon pagoda#china#chinese architecture#asian architecture#asia#chinese culture#asian culture#pagoda architecture#pagoda#buddhism#tang dynasty#photography#aesthetic#religion#asian religion#chinese religion#ancient china#ancient tradition#sun and moon

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to ask, how do people in China actually view Lego Monkie Kid?

No doubt that Lmk fandom as a whole has a major issue with drowning out the voices of people in China and the fact that this show is based on genuine relfion and mythology that is taken, from what I've heard and seen, quite seriously.

Now I've been a fan of the show for a very long time, so much so that it got me into researching and learning as much as I could about it jttw and the religion and mythology behind it all, which led to some interesting things I've noticed about it and the show as whole.

For one, lmk killing the Jade Emperor so quickly and easily was a bold move, seeing as it's the equivalent, from what I've seen, of taking Jesus and easily disintegrating him by throwing him down a flight of escalaters so hopefully they have an explanation for that later on. There's other things that have been pointed out like it not lining up 100% with the book and some minor things here and there, and people not understanding things cause they never read the book or because some things were changed and it was misinterpreted. However at the same time there have been many jttw adaptions (with this one being unique as it's more of a 'sequal') with some made by America and some made by China that also make changes here and there, from what I've seen and heard that are also loved.

Which leaves me a bit confused and to genuinely ask, how do people in China view lmk? Is it good or bad? Is it respectful or disrespectful? And is it okay for one to like and enjoy the show like me and many MANY others have been? I know it might seem like a silly question, but to overthinkers like me and many others out there (Yeah I see you), it can be pretty draining to think about how you could be enjoying a show that is harming others without you realizing it. So now I created this posts to hear your thoughts on it ^^

I do ask that it is kept civil as it's meant to teach and educate, not offend others or tear people down. I hope to hear your thoughts and learn more about all of this ^^

#china#chinese culture#chinese#chinese religion#chinese mythology#jttw#journey to the west#lego monkie kid#lmk#lego#monkie kid#show#tv series#tv shows#shows#series#animated series#culture#adaption#religion

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd say I'm becoming a nerd, but that ship sailed a long time ago. I guess I'm just expanding my nerdiness to other areas.

Anyway, MORE MYTHOLOGY!

So in Journey to the West, the Buddha explains that there are 4 'spiritual primates' that don't fit into any categories for immortals or types of creatures. Fans of Lego Monkie Kid are likely familiar with 2, the Stone Monkey Sun Wukong and the Six Eared Macaque. The other 2, the Long-armed Gibbon and the Red-Buttocked Baboon are a lot more obscure. They only get a brief mention in JttW because the focus of the chapter they appear in is Macaque, but the idea of a set of super powerful Immortal monkeys is just too fun to pass up, you know? So I've been thunking my thinker.

What if each primate was associated with a different realm (mortal, heavenly, lunar, and underworld) and element? I know the 4 elements (earth, water, wind, fire) are a western idea rooted in alchemy and eastern mythology has 5 elements (earth, water, fire, metal, wood), but there aren't 5 monkeys and this is just a thought experiment and not me trying to force western ideas onto eastern culture.

Got it? Good.

Now, Sun Wukong is very solidly earth because he's, you know, a rock. No surprise there. He was also born in the mortal realm and spent most of his life there, so we'll call him the celestial primate of the mortal realm while we're at it.

The Six-Eared Macaque is another easy one. A lot of LMK fannon associates him with wind, inferring that his heightened hearing has something to do with wind magic. He's also very closely tied to the moon because of the line in "Shadow Play" where he directly compares the Warrior (himself) to the moon. So Macaque is the celestial primate of wind and the Lunar realm.

Now here's where we get a bit more speculative and start using information creatively. There are 2 monkeys, realms, and elements left I want to use, so let's start with the monkeys so everyone has a baseline understanding.

The Long Armed Gibbon (Gibs, from now on) is described as being able to "seize the sun and moon, shorten a thousand mountains, distinguish auspicious from inauspicious, and manipulate planets and stars."

The Red Buttocked Baboon (Babs for short) has "knowledge of yin and yang, understands human affairs, is adept I'd daily life and can avoid death and lengthen its life."

Starting with the realms because they seem easiest to assign, I would give Gibs the Heavenly realm because of its ability to move around celestial objects like the sun, moon, planets, and stars. This leaves the Underworld to Babs, which I think fits nicely because their "knowledge of yin and yang" and "understand[ing] of human affairs" would make them a good assistant to the 10 Kings of the Underworld.

Next comes the 2 remaining elements, water and fire, which are a bit tricky because it could go both ways.

Gibs could be fire because the sun and stars are giant balls of burning plasma, but also water because the sky/heavens are often associated with an ocean or other bodies of water in several different mythologies. For example, in Egyptian mythology, Ra sailed his boat through the sky every day, while in early Abrahamic belief the sky was a huge dome with water on the other side, and rain happened when floodgates were opened to let the water through. In Chinese myth specifically, the Milky Way is often depicted as a river that is sailed through by various deities.

Babs could fit with fire as well because underworlds and hell-adjacent places are often shown to have fires to torment and punish the sinful dead, no surprise there. But there is surprisingly a lot of water symbolism in the realm of the dead as well. For example, some people may be familiar with the Japanese idea of the Sanzu River, very similar in concept to the Greek River Styx, as well as the Chinese Huang Quan/Yellow springs.

Personally I would pair Babs with fire because he has red in his name, making him the celestial primate of fire and the Underworld.

That leaves Gibs to be the celestial primate of water and the Heavenly realm.

I feel pretty good about this, but if anyone else has other ideas I'd love to hear them.

Sh*tpost Masterlist

#lego monkie kid#lmk#sun wukong#journey to the west#liu er mihou#six eared macaque#jttw#long armed gibbon#red buttocked baboon#crack theory#my theory#chinese religion#chinese mythology#4 elements#cool connection#no books this time we die like men#i've put more effort into this than i have most of my school or college research papers#maybe i should've been a mythology major...#shadowpeach#mythology sh*tposting#mythology#mythology and folklore#jttw inspo character ideas

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Folk Religion: Snowy edition

Recent snow storms where I live has got me thinking: is there a deity responsible for snowfall and winter in traditional Chinese religion?

You got Frau Perchta/Holle in Germanic folklore, Yuki-Ona in Japanese Shinto folk beliefs, Skadi in Norse Paganism, and Morana in Slavic mythology, but I haven't ever heard of such a figure from my elders growing up.

So for this one, I had to actually use my limited Mandarin skills to do research, along with some help from more fluent family members and friends.

It turns out there are more than one traditional winter & snow deities in Chinese folklore. The reason I personally didn't hear of any is because, again, Chinese folk religion is extremely regional. There are central major deities that are uniform but the rest all differs from region to region. Han Chinese people have always spread out across several climate zones, from tropical to sub-arctic. Understandably, Gods and Goddesses associated with weather will differ from region to region. My Chinese side of the family hailed from a region where snowfall isn't very common, and winter isn't normally extreme. But look towards regions north of the Yellow River, and it's more upstream valleys in the Han Chinese heartland, it's a different story.

Teng'Liu: The Spirit of Snow and Frost

The first deity I can find is a figure named Teng'Liu (藤六). This is a male deity associated with snow itself. The "Liu" part if his name is the Chinese character for 6. Snowflakes typically have six arms/branches regardless of pattern. In Chinese numerology, the number 6 is also a number with "extreme Yin energy" (极阴). Snow itself is a thing with a lot of Yin energy too, as it's formed from water. Those familiar with Chinese cosmology should be familiar with the element's association with the cardinal direction of North. Which, again, is attributed with Yin. Thus explains why many forms of his folk names contains the number 6.

There is a folk ritual (which thankfully hasn't been practiced in over a century), which in Northern villages they used to offer up a young girl to this snow deity as a gift to appease him. The unfortunate girl would be tied up in a sack and left to the elements in the cold.

Teng'Liu occurs often in poetic works of literature as a stand-in for "snow". A fitting example is a work from Song dynasty writer and poet Yang Wanli, where he mentions "The Azure Lady pulls along Teng'Liu, as the Sun wilts away as she shakes (him)"** The meaning is obvious, but he mentions an Azure Lady, which takes us to another deity.

Qing'nu (青女): The Azure Lady

The second deity associated with snow and winter is a Goddess called Qing'nu, or "The Azure Lady", "The Lady in Turquoise", "The Lady in Blue", depending on the translation. She seems to be much more well-attested in ancient religious texts in addition to poetry and seems to predate the emergence of Teng'liu.

Attested in Huainanzi, a text compiled around 139 BC, "...three moons into autumn, Qing'nu emerges (from her home), and makes frost and snow fall..."

She is also mentioned as having white hair in a lot of classical Chinese poetry.

In traditional Chinese folk beliefs, Qing'nu resides in the moon and is a companion/handmaiden of the Moon Goddess Chang'E (嫦娥). Every year at the end of autumn, she will emerge from the moon palace to perform her duty: to bring winter, frost, cold, and snow. She will descend upon Mount Qing'yao (青要山), where she will bathe in the waters there to purify herself. She will then start playing her seven-stranded lyre and snow and frost will fall upon the earth to cleanse the land of impurities and diseases (until they come back next summer).

BTW Mt. Qing'yao is an actual mountain in Henan Province. The mountain itself does play a rather big role in traditional beliefs and in Taoism. In fact, there is a hill adjacent to the mountain named Qing'nu's Peak (青女峰), where on the peak there stands a pillar-like rock. In local folklore they say that lone pillar looks like a slender lady, standing atop the mountains looking down upon the earth. It marks where the Goddess herself stands every year to bring winter. The locals call it "the maiden's rock" (闺女石).

Legend has it there was once a gorgeous palace at the foot of this mountain where Qing'nu would stay in temporarily during winter. This could possibly be a reference to some type of structure used as a shrine or temple. Today only the spring that flowed in the palace remain. The very spring that, according to folklore, that the Goddess herself bathes in to purify herself. Today, young ladies from around would make pilgrimage to that spring to welcome her arrival on 14th day of the ninth month. A second pilgrimage would also be made on 13th day of the third month as she is supposed to leave and return to the moon. (the dates are the dates in the Chinese lunar calendar).

From these we can see while those deities are all associated with snow, they are seen by the people as very different. Teng'liu is very embodiment of the weather phenomenon, kind of like Jack Frost in American folklore. The fact there were rituals to appease him means that he is seen as a very unpredictable and volatile force. A spirit which has to be controlled under strict orders from a higher Celestial deity (天神): Qing'nu. Think of her as the Chinese counterpart to Frau Holle, a spirit attributed to making snow fall but not the snow itself. Or rather, think of those two like Helios and Apollo in Greco-Roman mythology. One being the sun itself and the latter being the one who pulls the sun across the sky.

This was fun, i hope all you folks who are trying to connect to their ancestral beliefs found this useful.

**translation might be off, sorry. Middle Chinese is difficult even for fluent speaker who studies old literature, plus this was Middle Chinese in it's poetic form.

#chinese folk religion#folklore#chinese folklore#history#ancestors#witchblr#witches of color#han chinese#chinese diaspora#folk taoism#chinese mythology#chinese religion#folk religion#polytheism#world religions

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can/Do Bad People Cultivate The Great Inarticulate Dao?

Short answer: Yes, they most certainly do. The reason is the Dao's ability to penetrate and be a part of All Things.

What brings this to my attention is chapter 62 of the Dao de Jing, and I am working with Rudolph G. Wagner and William S. Wilson's translations and Wang Bi's commentaries.

The sections I want to focus on are as follows:

Wilson: "It (the Dao) is a treasure for the good man who is a blessing for all, and a place of support for the bad man, as it would carry him on its back as though he were a child."

Wagner: "It (the Dao) is what is treasured by good men. It is what men who are not good protect."

Two very different translations here. Not sure which one I prefer, but regardless, working with two or more translations is an essential component for studying the Dao de Jing or any other Daoist literature, as an English-only reader.

The first thing that is glaring to me is the Dao's non-discriminatory qualities. For the bad person and the good person alike, both confide in the Dao, even if their crafts differ. For the bad man, we will use the character of a thief, and for the good man, someone who is pious and an upstanding, law-abiding citizen, and perhaps someone with privilege (someone with political status or a well-respected business person). If we recall the story of Lord Wenhui and Cook Ding in book three of the Zhuangzi, we can see that even for someone with high status, and more privilege, it is not enough to cultivate the Dao. In that story, Cook Ding astonished Lord Wenhui with his mastery and cultivation of the inarticulate Dao. Rich or poor, rank, privilege, and societal status are never prerequisites for cultivating and mastering the Dao. For more on this story, please take a look at my commentary on this particular section of the Zhuangzi.

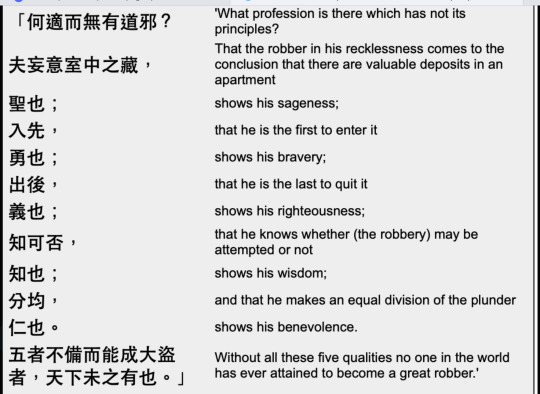

So the Dao makes no distinctions between the good and bad man, okay, cool. So does this mean a thief can practice their craft with Virtue and in step with the Dao? According to Zhuangzi, yes. In a section I have not read yet, Robber Zhi's disciples ask him if there is such a thing as the "Dao of thieving?" To which Robber Zhi responds: "Which profession is there that has not its (The Dao's) principles?"

As seen above in the picture, the thief exudes the principles of the Dao.

As suggested by Wang Bi's commentaries on these verses from chapter 62, the one who is bad and practices the Dao, they avoid harm and the punishment of their thievery. When taken at a surface level-reading, this sounds like Daoism or the Dao itself excuses bad behavior. But this is not the case. What this is saying, I think, is that the Dao and Virtue are the bedrock of the world. As suggested in the photo above, the thief cannot but help to practice thievery with at least some virtue and principles that are in accordance with the Dao. Daoism doesn't promote thievery or any kind of bad behavior, but it encourages us to be true to our nature, be true to ourselves and our circumstances, and act accordingly to what Fate presents us.

I wish to impose a suggestion that when a thief practices thievery in step with the Dao and its principles, they can eventually turn away from their life of crime. This sentiment is not explicitly mentioned in the Zhuangzi or Wagner's translations of chapter 62. But if we turn to Wilson's translation of the last few words in his copy of the Dao de Jing, it states as follows:

"Why did the men of old treasure this Way? Didn't they say that those who seek it out will pick it up along the way, and that those who have been caught like fish in the nets of crime will be pardoned and given new life? Thus, it makes all under Heaven treasure it.

Compare it with Wagner's:

"What is the reason why the ancients valued this Way? Did they not say: If the good ones strive by means of the Way, they will achieve it, while those who have committed crimes avoid punishment by means of The Way? That is why it (The Dao) is most valued by All Under Heaven."

As you can see, Wagner's translation still gives off a vibe that the Dao excuses those who commit crimes and can thus avoid apprehension and repercussions. While this is one correct way to look at it, we must dig deeper into what the text is trying to tell us. I will take advantage of this opportunity to stress again the importance of working with two or more translations with these kinds of texts.

Focusing on Wilson's translation gives more leniency to my imposition that the thief can eventually turn away from their life of crime when they practice Virtue and the principles that are in accord with the inarticulate Dao. While it may be argued that the thief or good man has no choice but to rely on Virtue and the Dao in their craft, as suggested by the photo of the excerpt from the Zhuangzi, I dare say there is a choice. Some people are ultra-violent and have no code of conduct for their crimes; I can attest this much from first-hand, anecdotal experiences from my life as a former thief. We must remember the Dao supersedes and transcends all human-noted distinctions (Zhuangzi chapter 2) and that any Dao that can be articulated is not the Unchanging Dao (Dao de Jing 1). What "is" good and what "is" bad has no room when embarking on the Inarticulate Dao. The only example I can give you, wonderful people, is my own life experience with crime and turning away from that.

When my old using buddies and I would embark on a boosting heist (I'm making this sound all fancy, but it's really just a clever way to steal from department stores in plain sight), we would only steal what we need to get to feel better, get high and put food in our bellies. We never robbed people at gunpoint; no threats or violence had ever ensued. Did we practice thievery in step with Dao and its Virtue? Perhaps, perhaps not. But as suggested in the picture above of Robber Zhi speaking to his disciples, we practiced all of those things unknowingly, of course. It is truly an anomaly that we were never apprehended and faced repercussions. We can throw out any suggestion of white privilege because I was just the driver, not the one actually going into the stores and performing the boost. The ones who got their hands "dirty" were all people of color. Though, I'm not suggesting at all that my hands were ever "clean" because I was just a mere getaway driver. I am simply pointing out that race had no play in our evading of repercussions.

Here we were, as suggested by Wilson's translation, all caught up in the nets of crime such as drug dealing and purchasing, and thievery. I know of two people who have been pardoned and given new life, myself and the one who actually would go in and perform the boost. I've kept in contact with the "master thief" who would actually go into these department stores and perform the boost. He is sober, doesn't steal or boost anymore, and has a well-paying job; and importantly was never arrested for these crimes we committed together. Whether he is telling me the truth is beside the point because I, too, have turned away from my life of crime, and it seems like my friend has, too. If he did face repercussions, then, of course, my white privilege could've been a massive factor in my evading repercussions for these particular crimes. My friend has no reason to lie about this, though. So I can't help but think that both of us (when mainly it was just us two doing the boots/thievery) evaded harm and repercussions because we practiced our craft with Virtue as our bedrock. We are both good people who didn't wish to live such a life that was fueled by petty crime and drugs. With our Virtue still intact, we escaped the vicious cycle of drugs and petty crime.

So, in conclusion, yes, both "good" and "bad" people cultivate the Dao and its Virtue. We should not "gatekeep" the Dao and its teachings to only the good, pious person. The Dao and all its teachings should be available to everyone: the Cook, the beggar, the thief, and the King. The Dao doesn't discriminate between our petty human distinctions, and we should be more aligned with Nature's natural distinctions. Just as the Dao is a treasure for the goodman who is a blessing for all, it (the Dao) is equally there for the bad person and is its place of support.

#daoism#philosophy#zhuangzi#dao dejing#taoism#tao te ching#chinese religion#chinese philosophy#lao tzu#laozi#dao de jing

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would you exclaim (euphemistically or non-euphemistically) using the name of the Archons…?

Actually, how would euphemisms of the Archons work (think gosh or golly for God)…?

Canonical Chinese terms for Morax in Liyue include: 岩王帝君 (Yán Wáng Dìjūn),帝君 (Dìjūn),岩王爷 (Yán wángyé), 他老人家 (tā lǎorénjiā, Chinese honourific meaning that old man).

By the way, 岩王爷 and 他老人家 are used by Yun Jin in her “About the Vision” voiceline in relation to her Geo Vision. (In the English localization she calls him Lord of Geo and the old man, respectively.)

Let it be known that in Mandarin, 岩王爷 (despite using 岩 which is stone, localized as Geo for the element) is a homonym of 阎王爷 (Yán wángyé), who’s the King of Hell in ancient Chinese religions. Other terms for this deity in real life include 阎罗王 (Yánluó wáng), 阎罗 (Yánluó), and 阎罗大王 (Yáluó Dàwáng) in Mandarin, and यम (Yama-raja) in Sanskrit (in Hinduism).

(From Baidu Baike page “阎罗王 (中国古代神话中的十殿阎王之一 )” and the Wikipedia page on “Yama (Hinduism)”)

Rex Lapis’ page on the Genshin Impact wiki also states

“His Chinese title, 岩王帝君 Yánwáng Dìjūn, "Imperial Sovereign Yánwáng; Stonelord Sovereign; Rex Lapis" includes the honorific title 帝君 dìjūn, "sovereign," typically added to the names of Daoist deities.”

(The page also has some great discussions on the etymologies of Morax’s titles in the comments.)

Technically speaking, 岩王帝君 in pinyin would be written as Yán Wáng Dìjūn because 岩 means rock or stone, and 王 means lord or king, and thus 岩王 (meaning rock king, stone lord, Lord of Geo if you will) is not one word and would not be transcribed as Yánwáng. (So if anyone could edit pinyin transcriptions of the tile on the wiki that’d be great.)

For 阎王爷, 阎 is also part of the name and 王爷 is the honorific..

…Hm.

(Spoilers for Neuvillette’s profile line after completing Masquerade of the Guilty.)

.

Neuvillette in the English localization of his “About the Geo Archon” profile line calls the Geo Archon Deus Auri (Latin: God of Gold) who has the Authority of Geo. In the original Chinese text, the first is 贵金之神 (Guìjīn zhī Shén, God of Gold), and the second is 岩之大权 (Yán zhī Dàquán). Hmm… 贵金 possibly comes from 贵金属 (Guìjīnshǔ) which is precious metal, referring to such as gold, silver, and platinum… Well, it’s likely a cultural difference between Liyue and Fontaine that resulted in such titles.

Looking at the (English localization of the) diegesis, with the Iudex of Fontaine calling the Geo Archon Deus Auri, it makes less sense that in the English localization, Liyue people would use the Latin term Rex Lapis for him when in contrast the Inazuma people refer to Ei and the Shogun puppet as Raiden Shogun.

I think… It’d make sense for Fontainians or Mondstadters to call him Rex Lapis.

#dusk rambles#Morax#Genshin impact#linguistics#sociolinguistics#yanwang dijun#Rex lapis#Yan wang dijun#chinese religion#Chinese#Genshin translation#Genshin lore#Genshin analysis#worldbuilding#English translation#Neuvillette#Fontaine#Liyue#岩王帝君#原神#language#dusk analysis

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of The Hermit, 1955. We can see clearly in the centre of the character: the yin and yang.

.

Detalhe de O Ermitão, 1955. Remedios Varo comentou a pintura e a presença do Yin e Yang em uma carta para seu irmão Rodrigo. Você pode ler mais sobre aqui.

.

#remedios varo#yin and yang#chinese religion#surrealism#surrealismo#esoterismo#chinese philosophy#filosofia chinesa#mulheres artistas#pintoras#mulheres pintoras#women artist#andré breton

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meng Po

In Chinese mythology and religious beliefs, Meng Po emerges as a significant figure associated with the realm of the afterlife. Known as Meng Po Niang, she assumes the role of a soul-retrieving deity within the Chinese underworld. Mythology narrates her pivotal task of concocting a potion known as the "soup of oblivion", "forgetfulness soup" or simply "Meng Po's soup." Upon reaching the underworld, it is believed that departing souls must partake in Meng Po's soup before embarking on their journey of reincarnation. This mystical elixir possesses the power to erase memories of past lives, ensuring a clean slate for subsequent rebirths. Depicted as an elderly woman, Meng Po administers her soup near the Bridge of Forgetfulness—a crucial point where souls traverse into their new existence. Her presence and the consumption of the soup serve as a spiritual purgation, enabling souls to relinquish their previous experiences and venture forward into the cycle of life and death. Consequently, Meng Po occupies a prominent position in Chinese literary, artistic, and religious expressions related to death and the afterlife, embodying the concept of renewal and the transformative nature of reincarnation within Chinese mythology and religious practices.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

When's Sun Wukong birthday too?

The Monkey King has several birthdays/religious celebrations. Here is a list written by a worshiper from Singapore:

I've independently verified numbers one to four via almanacs and informants. I think five and six are maybe traditions in her family.

This is a picture I took during Monkey's 8/16 lunar birthday (i.e. no. 2) in Hong Kong in 2018.

I saw your other ask. I'll answer that when I get the chance.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#birthday#chinese folk religion#Chinese religion#JTTW#lego monkie kid#LMK

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was looking into some idols my friend Pilgrim Sun had referred to me and I happened upon numerous idols of both Muzha and Jinzha.

Ordinarily this wouldn’t be a problem, however Muzha is known primarily to use the Hooks of Wu and not melon hammers. Similarly, Jinzha is known to use a staff somewhat similar to Sun Wukong but is pictured to be using two swords. This may be a regional difference between China and Taiwan, but something for me to look into further nonetheless.

Images of idols of Nezha from Taiwan for reference (the first image is from Pilgrim Sun).

#nezha#li nezha#the legend of nezha#third lotus prince#li muzha#muzha#li jinzha#jinzha#wooden scholar#gold tactician#chinese religion#daoism#chinese gods#chinese deities#chinese mythology#chinese culture

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHƯƠNG 8 DỊ TÍNH (易 性)

Hán văn:

上 善 若 水. 水 善 利 萬 物 而 不 爭, 居 眾 人 之 所 惡, 故 几 於 道. 居 善 地, 心 善 淵, 與 善 仁, 言 善 信, 政 善 治, 事 善 能, 動 善 時. 夫 唯 不 爭, 故 無 尤.

Phiên âm:

Thượng thiện nhược thủy.

Thủy thiện lợi vạn vật nhi bất tranh, xử chúng nhân chi sở ố, cố cơ [2] ư Đạo.

Cư thiện [3] địa, tâm thiện uyên, dữ [4] thiện nhân, ngôn thiện tín, chính thiện trị, sự thiện năng, động thiện thời.

Phù duy bất tranh, cố vô vưu. [5]

Dịch xuôi:

Bậc trọn lành giống như nước.

Nước khéo làm ích cho muôn loài mà không tranh giành, ở chỗ mọi người đều ghét, cho nên gần Đạo.

Ở thì lựa nơi chốn; tâm hồn thời thâm trầm sâu sắc; giao tiếp với người một mực nhân ái; nói năng thành tín; lâm chính thời trị bình; làm việc thời có khả năng; hoạt động cư xử hợp thời.

Chính vì không tranh, nên không ai chê trách oán thán.

Dịch thơ:

Người trọn hảo giống in làn nước,

Nuôi muôn loài chẳng chút cạnh tranh.

Ở nơi nhân thế rẻ khinh,

Nên cùng Đạo cả mặc tình thảnh thơi.

Người trọn hảo, chọn nơi ăn ở,

Lòng trong veo, cố giữ đức nhân.

Những là thành tín nói năng,

Ra tài bình trị chúng dân trong ngoài.

Mọi công việc an bài khéo léo,

Lại hành vi mềm dẻo hợp thời.

Vì không tranh chấp với ai,

Một đời thanh thản, ai người trách ta.

click to < BÌNH GIẢNG > pha tạp thì dễ, giữ được ban sơ như nước mới khó. Thứ đơn giản bình thường, mới khó tìm, chỉ có giản thường mới là hiếm khó, khó tìm, khó giữ nhất.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

veneration

0 notes

Video

youtube

AMERICAN BORN CHINESE Trailer (2023) Michelle Yeoh

#youtube#american born chinese#comedy#series#drama#martial arts#chinese religion#fights#quest#trailer

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Spring Festival folk custom local to Chaoshan (Chaozhou and Shantou, Guangdong province) called 盐灶拖神/Yanzao tuoshen ("Yanzao (a village in Yanhong town, Chenghai district, Shantou city) God dragging").

This local custom falls under the greater folk custom of 游神/youshen ("walking the gods"). For youshen customs, and more specifically in Yanzao tuoshen, there is a "god walking team" responsible for carrying the palanquin upon which the god Ying Laoye (营老爷) sits. Ying Laoye is a protector deity local to Chaoshan. The custom of god-walking is not only related to prosperity but also is meant to strengthen the ties of the clans in the villages, and remind the people of their bond; Yanzao is what is known as a "natural village" (自然村落), a village that has been formed naturally after a long period of settlement by villagers whose main occupation is agriculture/farming. The village forms its own customs with family at the center of many of them, as many of the villagers are related. For example, Yanzao has about 20k people divided into four districts; among those numbers, there are about 10k surnamed Lin, 5k surnamed Chen, and 1k surnamed Li and Zhou.

When it comes to Yanzao tuoshen, the god walking team is tasked with safely carrying the god through the village. In the above video, the team is all wearing white. They will often wield incense that they use to hit outsiders with. In other tuoshen processions, the god walking team may be shirtless, their bodies covered in oil to make it difficult for outsiders to grab them and pull them out of the way. The goal of the outsiders is to find a way to get to the palanquin. If the outsiders are able to get onto the palanquin and maintain the position for a length of time, it will bring them good luck. However, surrounding people will usually very quickly pull them down again. If the palanquin is taken over by outsiders, then a "god saving team" will be dispatched to take back the palanquin and continue carrying it through the village.

Usually by the end of the procession, the god is dragged down from the palanquin and is broken apart and sunk into a body of water. On a later auspicious date, the god will then be fished back up, repaired, and returned to the temple for worship. This is meant to bring luck to the villagers.

One folk legend regarding this custom tells that there was once a very poor villager whose turn it was to worship the god, a custom which required him to treat the other villagers to a banquet. However, the poor villager was really too poor, and had no way of supporting others, so he secretly took the god's statue and dragged it to the seaside, burying it there and then running off in the night to Nanyang. Unexpectedly, that year, the village saw bountiful harvest and the poor villager also struck great fortune in Nanyang, leading the villagers to wonder if perhaps the god enjoyed being carried away. This is said to have lead to the tradition of dragging the gods.

Sources (Chinese):

盐灶拖神偶

澄海盐灶拖神习俗的文化解读

自然村落

730 notes

·

View notes